Abstract

Background:

Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash has earned eponym of gold standard to treat and/or prevent periodontal disease. However, it has been reported to have local side-effects on long-term use. To explore a herbal alternative, the present study was carried out with an aim to compare the anti-plaque efficacy of a herbal mouthwash with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash and normal saline.

Materials and Methods:

It was an examiner-blinded, parallel designed clinical trial, in which 90 pre-clinical dental students with gingival index (GI) ≤1 were enrolled. To begin with, GI and plaque index (PI) were recorded. Then, baseline plaque scores were brought to zero by professionally cleaning the teeth with scaling and polishing. After that, randomized 3 groups were made (of 30 subjects each - after excluding the drop-outs) who were refrained from regular mechanical oral hygiene measures. Subjects were asked to swish with respective mouthwash (0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash, herbal mouthwash, or normal saline) as per therapeutic dose for 4 days. Then, GI and PI scores were re-evaluated on 5th day by the same investigator, and the differences were compared statistically by ANOVA and Student's ‘t’-test.

Results and Observations:

Least post-rinsing GI and PI scores were demonstrated with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash, followed by herbal mouthwash and highest scores with normal saline. The difference of post-rinsing PI scores between the chlorhexidine and herbal mouthwash groups was statistically non-significant, whereas this difference was significant between chlorhexidine and saline groups, and the difference between herbal and saline groups was non-significant. It was concluded that 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash remains the best anti-plaque agent. However, when socio-economic factor and/or side-effects of chlorhexidine need consideration, presently tested herbal mouthwash may be considered as a good alternative.

Keywords: Anti-plaque efficacy, chlorhexidine, gingival index, herbal, mouthwash, plaque index

INTRODUCTION

Chemical inhibitors of plaque play an important role in plaque control.[1] A variety of approaches have been considered for chemical plaque control.[2] Most products in current use or under study are antiseptics.[3] Vehicles for delivery of chemical agents with anti-plaque/anti-gingivitis action are toothpastes, mouthwashes, spray, irrigators, chewing gum, and varnishes.[4] However, mouthwashes are a simple and widely accepted method to deliver the anti-microbial agent (after toothpastes), which can be used by the patient as an oral hygiene aid.[5]

Chlorhexidine gluconate is an antiseptic mouthwash much in demand. This cationic bis-biguanide is the best known and most widely used member of the class of broad-spectrum antiseptics.[2] It is effective against an array of micro-organisms, including gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, fungi, yeasts, and viruses. It exhibits both anti-plaque and anti-bacterial properties.[6] It acts by altering integrity of cell membrane of bacteria. Its superior anti-plaque activity is the result of its substantivity and pin-cushion effect.[7–9]

Any bacteria adhering to the tooth surface are challenged by chlorhexidine molecules. Depending on the bacterial species and the amount of chlorhexidine attached to the tooth surface, these micro-organisms are either killed or are simply prevented from multiplying. This bacteriostatic effect of chlorhexidine is what makes it the gold standard – plaque is prevented from forming because the bacteria attaching the tooth surface cannot multiply. When used as a mouthwash, its mode of action is purely topical and because it is poorly absorbed systemically, it is regarded as a relatively safe drug.[10]

In nut shell, chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash has served the dental profession over 3 decades. It has remained as a primary agent for chemical plaque control, its clinical efficacy, and side effects being well-known to the profession. In addition to having gained the acceptance of the dental profession, chlorhexidine has also been recognized by the pharmaceutical industry as the positive control, against which the efficacy of alternative anti-plaque agents should be measured.[11]

However, this mouthwash has been reported to have a number of local side-effects (Flotra et al. 1971)[12] on its long-term use like brown discoloration of teeth, some restorative materials and dorsum of tongue; taste perturbation; oral mucosal ulcerations and paresthesia; unilateral/bilateral parotid swelling, and enhanced supra-gingival calculus formation.

Taking into consideration the side-effects of chlorhexidine, and the liking or faith of people for herbal/natural products like miswak, the present study was conducted with an aim to compare the anti-plaque efficacy of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash (positive control designated as A) and the herbal mouthwash (experimental group named as B) with normal saline (as negative control - C). This study compared the “de-novo” plaque formation between the 3 groups (A, B, and C) during 4-day cessation of mechanical plaque control using a 4-day plaque re-growth model.[13]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was an examiner-blinded, parallel designed clinical trial carried out in Department of Periodontics, Modern Dental College and Research Centre, Indore. It included a total of 90 pre-clinical dental students who were enrolled for B.D.S. course (42 males and 48 females, in the age range of 18 to 25 years). The ethical clearance for the study was availed from the ethical committee of the institution, and informed consent was taken from all the participants of the study. Based on analyses of previous 4-day plaque re-growth studies, it was estimated that 90 participants (30 in each group) would be required in this study to provide sufficient power to detect a difference between the GI and PI scores of the 3 mouthwashes.

Materials used were diagnostic instruments, scalers, polishing cups, abrasive paste, 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash, herbal mouthwash, normal saline, sterile dispensing dark colored bottles, measuring cups, and plaque disclosing agent.

Major contents of this herbal mouthwash are: Babool chaal/Acacia arabica (20% w/v) as an astringent, darim leaves/Punica granatum (10% w/v) as an astringent, chameli leaves/Jasminum grandiflorum (10% w/v) as an anti-microbial, mulethi/Glycyrrhiza glabra (5% w/v) as an astringent and neem/Azadirecta indica (2% w/v) as an astringent and an anti-microbial agent. Other contents (in small quantities) are: Alum (1.5% w/v), suhaga (1% w/v), kapoor (0.5% w/v), laung (1% w/v), and menthol (0.5% w/v).

Indices used were gingival index or GI (Loe and Silness, 1963)[14,15] on all teeth, except third molars with 4 sites per tooth - mesial, distal, facial, and palatal/lingual and plaque index (Turesky et al. 1970),[16] which is a modification of the Quigley and Hein plaque index (1962)[17] (on all teeth, except third molars).

Inclusion criteria

Systemically healthy subjects with GI≤1 (as a mean value for all tooth surfaces scored), a dentition of ≥20 teeth with a minimum of 5 teeth per quadrant were enrolled in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects with severe mal-alignment of teeth, orthodontic appliances, fully crowned teeth, removable partial dentures; tobacco consumers, and subjects with medical or pharmacological history that could compromise the conduct of the study were excluded.

Study design

90 pre-clinical dental students (from I and II B.D.S. courses) with GI≤1 from Modern Dental College were enrolled in the study. At the start of the study period, baseline recordings (GI and PI scores) were made in order to assess the oral hygiene level of the subjects. All recordings were made by the same examiner. After disclosing plaque, baseline plaque scores were brought to zero by professional scaling and polishing with rubber cups and an abrasive paste. Intra-oral colored photographs were taken. Then, subjects were assigned randomly (in order to eliminate personal bias in selection of the sample, simple random sampling i.e., lottery method[18] was used after fitting into inclusion and exclusion criteria and willingness of the subjects for participation in the study) to 1 of the 3 groups (of 30 subjects each) who were refrained from regular oral hygiene measures (tooth brushing and dental flossing), except for swishing with respective mouthwash as per therapeutic dose. Group A subjects were instructed to rinse with 10 ml of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash twice daily for 1 minute (standard regimen for chlorhexidine mouthwash[19]). Group B subjects were requested to rinse with 5 ml of herbal mouthwash diluted with 5 ml of water twice daily for 1 minute. Herbal mouthwash is a concentrate and was diluted 1:1 with water according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Group C subjects were asked to rinse with 5 ml of normal saline (as the experimental/herbal mouthwash was also used only 5 ml as a concentrate) twice-a-day for 1 minute. This regimen for each group was followed for 4 days, and participants were asked to enter in a handy calendar provided to them (so that they do not forget to rinse). GI and PI scores were re-evaluated on the 5th day by the same investigator who was unaware of the mouthwash used by the subject. Post-rinsing GI and PI scores of groups A, B, and C were then compared statistically by ANOVA and student's ‘t’-tests. Side-effects of mouthwashes were evaluated from subjects of all the 3 groups by means of a questionnaire as well as by means of clinical examination.

In the questionnaire, subjects were requested to mention yes/no for pain, burning sensation, pruritis/itchiness, dryness of the mouth, taste disturbance, discoloration of teeth and tongue surfaces, feeling of bitter taste in the mouth after a 4-day use of the 3 mouthwashes. The patients were asked to rate the severity of side effects as none, mild, moderate, or severe. With respect to the taste disturbance side-effect, the subjects were also asked to specify which taste (i.e., salt, bitter, sweet, or sour) had altered in perception.

By means of clinical examination, following side-effects were evaluated:

-

(a)

The severity of soft tissue irritation, rated as none, change in color, desquamation or presence of aphthae

-

(b)

Discolorations (staining of the tongue and tooth surface) were recorded as present/absent and if present, further classified as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

At the end of the study, the tooth stains were observed intra-orally by the same examiner who recorded pre-and post-rinsing PI and GI scores. Photographs were taken of those patients in whom the stains were present. These photographs were then projected in a random order and a clinician, who was unaware of the study protocol, was asked to rate, over two separate sessions, the severity of tooth discoloration, to evaluate the intra-observer reliability.

Subjects returned to their habitual oral hygiene measures after the completion of the study period.

RESULTS

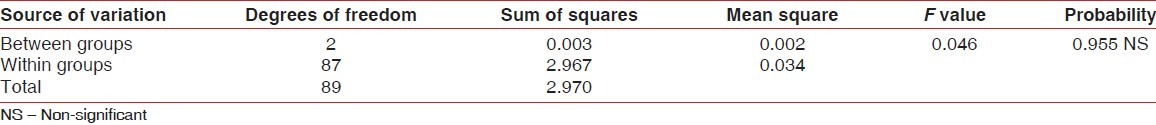

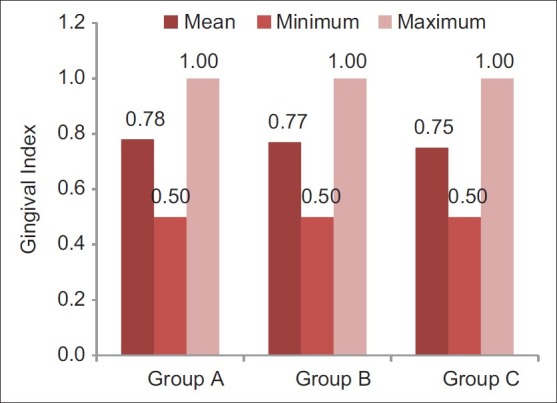

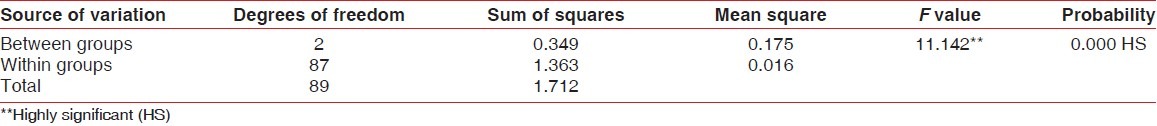

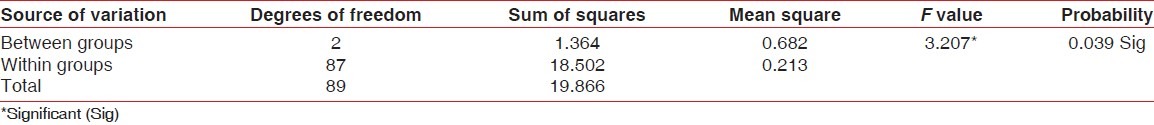

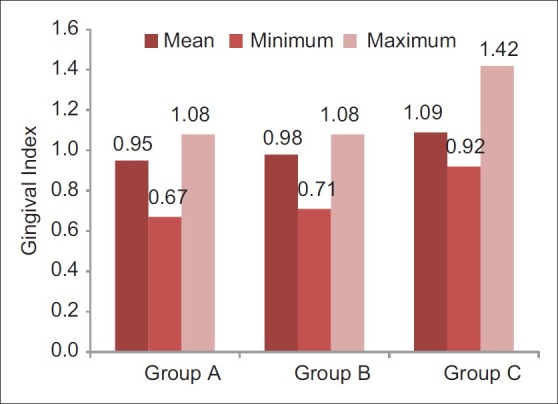

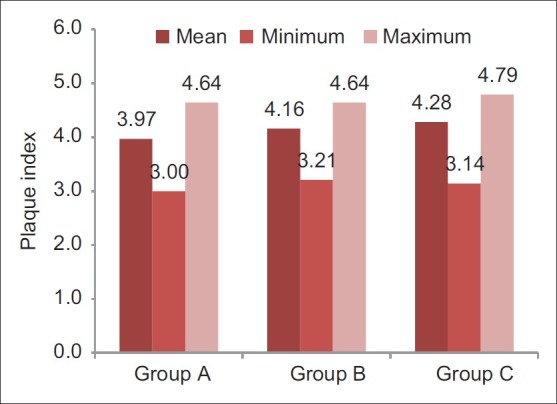

Participants sincerely followed the protocol of the study, and no systemic side-effects were observed in these subjects. Mean age of subjects in group A was 19.3±1.1, that in group B was 19.0±0.7, and that of subjects in group C was 19.4±1.1. Table 1 and Figure 1 show ANOVA test for difference between pre-rinsing GI scores of the 3 groups. There was no significant difference between mean GI of the 3 groups at pre-rinsing stage. Table 2 and Figure 2 show ANOVA test for difference between pre-rinsing PI scores of the 3 groups. There was no significant difference between PI scores of the 3 groups at pre-rinsing stage. Mean GI at post-rinsing stage was least with group A subjects (0.95±0.13), followed by group B subjects (0.98±0.09) and then group C subjects (1.09±0.15). Similarly, mean PI at post-rinsing stage was least with group A subjects (3.97±0.53), followed by group B subjects (4.16 ± 0.41) and then group C subjects (4.28±0.44).

Table 1.

ANOVA for pre-rinsing gingival index scores of different groups

Figure 1.

Pre-rinsing gingival index scores of different groups (Internal scale on vertical axis: 0.2 units)

Table 2.

ANOVA for pre-rinsing plaque index scores of different groups

Figure 2.

Pre-rinsing plaque index scores of different groups (Internal scale on vertical axis: 1.0 unit)

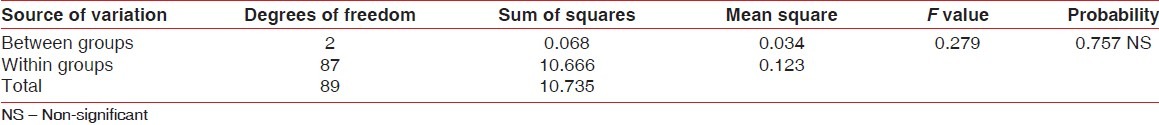

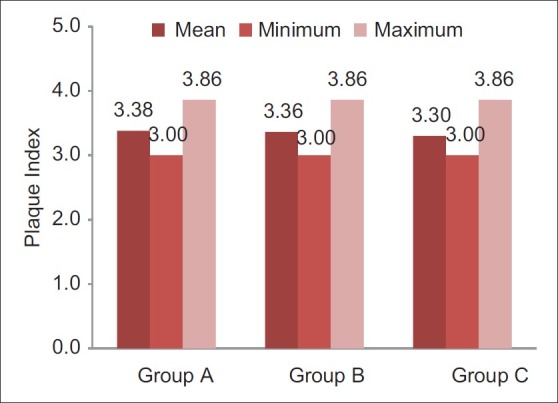

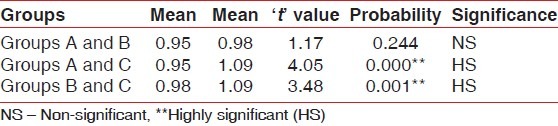

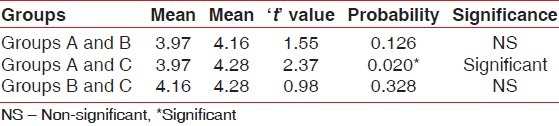

Differences between post-rinsing GI and PI scores were also evaluated by ANOVA test [Tables 3 and 4]. Table 3 shows that there was a highly significant difference for post-rinsing GI scores between the 3 groups at probability value 0.000 and F value 11.142. Table 4 shows that there was a significant difference for post-rinsing PI scores between the 3 groups at probability value 0.039 and F value 3.207. Furthermore, the differences in GI and PI scores between the 3 groups at post-rinsing stage were also evaluated by ‘t’-test [Tables 5 and 6]. Table 5 and Figure 3 show that the difference of post-rinsing GI scores between the group A and group B was non-significant at probability value 0.244 and ‘t’ value 1.17, this difference was highly significant between groups A and C at probability value 0.000 and ‘t’ value 4.05, and the difference between groups B and C was also highly significant at probability 0.001 and ‘t’ value 3.48. Table 6 and Figure 4 show that the difference of post-rinsing PI scores between the groups A and B was non-significant at probability value 0.126 and ‘t’ value 1.55, this difference was significant between groups A and C at probability value 0.020 and ‘t’ value 2.37, and the difference between groups B and C was non-significant at probability 0.328 and ‘t’ value 0.98.

Table 3.

ANOVA for post-rinsing gingival index scores of different groups

Table 4.

ANOVA for post-rinsing plaque index scores of different groups

Table 5.

‘t’ values for post-rinsing gingival index scores of the different groups

Table 6.

‘t’ values for post-rinsing plaque index scores of the different groups

Figure 3.

Post-rinsing gingival index scores of different groups (Internal scale on vertical axis: 0.2 units)

Figure 4.

Post-rinsing plaque index scores of different groups (Internal scale on vertical axis: 1.0 unit)

Subjective opinions of the participants were evaluated after 4 days of mouthwash use. Staining (mild brown discoloration of teeth) was found in 19 subjects in group A (estimated visually and from the colored photographs). 16 subjects in group A reported an unpleasant taste (mild alteration in taste for salty foods/drinks). 11 subjects in group B experienced mild/slight bitter taste. Staining was not observed in group B subjects.

DISCUSSION

Few studies have been done with relatively favorable results exhibited by herbal/natural product mouthwashes. Scherer, et al.[20] compared herbal mouthwash and distilled water in a study. They evaluated Loe and Silness GI and found lower scores with herbal mouthwash as compared to distilled water. Khalessi, et al.[21] in their study compared the oral health efficacy of Persica mouthwash (herbal mouthwash containing an extract of Salvadora persica) with that of a placebo. Plaque accumulation and gingival bleeding were measured before and immediately following the experimental period. They concluded that herbal mouthwash resulted in improved gingival health when compared with pre-treatment values. A study done by Almas, et al.[22] assessed the anti-microbial activity of 8 commercially available mouthwashes and 50% miswak extract against 7 micro-organisms. They concluded that mouthwashes containing chlorhexidine were with maximum anti-bacterial activity, while cetylpyridinium chloride mouthwashes were with moderate and miswak extract was with low anti-bacterial activity. Moran, et al.[23] conducted a study on comparison of a natural product, triclosan and chlorhexidine mouthwashes in a 4-day plaque re-growth model. They concluded that the natural product was second to chlorhexidine in plaque inhibition. Studies on the plant extract sanguinarine chloride mouthwash and toothpaste have shown that it produces moderate reductions in plaque and gingivitis.[24,25] Furthermore, iminium ion in sanguinarine, which is responsible for its activity, is retained in plaque for several hours after use and is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.[26]

As evident from the results of our study, there was no significant difference between GI and PI scores of the 3 groups at pre-rinsing stage. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the mean age of subjects in the 3 groups. This means that the population selected for each of the 3 groups was homogenous. Mean GI and PI scores at post-rinsing stage were least with group A subjects, followed by group B and then group C.

The difference of post-rinsing GI scores between the groups A and B was statistically non-significant, whereas this difference was highly significant between groups A and C, and the difference between groups B and C was also highly significant. The difference of post-rinsing PI scores between the groups A and B was statistically non-significant, whereas this difference was significant between groups A and C, and the difference between groups B and C was non-significant. This suggests that herbal mouthwash has an anti-gingivitis effect also, statistically comparable to that of chlorhexidine mouthwash. Though the post-rinsing plaque scores were statistically comparable in groups B and C, post-rinsing GI scores showed a highly significant difference with lower scores in group B subjects. This can be attributed to the astringent and anti-microbial properties of this herbal mouthwash, because of which, inspite of considerable post-rinsing plaque score with group B, corresponding GI score was not appreciable.

Subjects on 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash exhibited mild brown staining of teeth, which was not observed in herbal mouthwash subjects. Moreover, herbal mouthwash is cost-effective as compared to the cost of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash. Therefore, in low socio-economic status population, presently tested herbal mouthwash can be a better alternative to 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash. Although the effect on plaque re-growth and gingival inflammation observed with chlorhexidine mouthwash was superior to that of herbal mouthwash, the latter did not cause many side-effects. Furthermore, the difference of post-rinsing GI and PI scores between groups A and B was not statistically significant. This means that anti-gingivitis and plaque-inhibiting properties of chlorhexidine and herbal mouthwash are similar.

Limitations of this study are:

A 4-day period is insufficient to evaluate anti-gingivitis property of this herbal mouthwash

A cross-over design with wash-out period would have been more authenticating as it eliminates the bias of variable host response.

Therefore, future studies can be directed towards testing the anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis efficacy of herbal mouthwash in a long-term period, which can also throw some light on advantages and disadvantages of this herbal mouthwash.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this 4-day “de-novo” plaque formation study, it was concluded that 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash remains the best anti-plaque agent; of course, it goes without saying that it is the gold standard mouthwash. However, when socio-economic factor, side effects of chlorhexidine and/or liking of the population for natural products need consideration, presently tested herbal mouthwash may be considered as a good alternative. However, future studies (with a long-term rinsing period) can be done to extrapolate the advantages and disadvantages of this herbal product.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our heartfelt thanks go to teaching and non-teaching staff of the Department of Periodontics, Modern Dental College and Research Centre, Indore for all the help and facilities provided for this study. We also thank all the student participants who were a part of the present study and sincerely acknowledge their efforts in complying with the requirements of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perry DA. Plaque control for the periodontal patient. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, editors. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders; 2006. p. 728. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel ID. Chemotherapeutic agents for controlling plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:488–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandel ID. Antimicrobial mouthrinses: Overview and update. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125(Suppl 2):2S–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(94)14001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Addy M. The use of antiseptics in periodontal therapy. In: Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP, editors. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 4th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2003. p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyle DM. Chemotherapeutics and Topical Delivery Systems. In: Wilkins EM, editor. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Company; 2005. p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahesh CP, Peter S. Plaque Control. In: Peter S, editor. Essentials of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Arya Publishing House; 2003. p. 447. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell AD, Chopra I. Antiseptics, disinfectants and preservatives: Their properties, mechanisms of action and uptake into bacteria. In: Russell AD, Chopra I, editors. Understanding antibacterial action and resistance. London: Ellis Horwood; 1990. p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Addy M. Chlorhexidine compared with other locally delivered antimicrobials. A short review. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:957–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornman KS. The role of supragingival plaque in the prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases. A review of current concepts. J Periodont Res. 1986;21(Suppl):5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sosa KV. Plaque Control. In: Peter S, editor. Essentials of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 1st ed. New Delhi: Arya Publishing House; 1999. p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CJ. Chlorhexidine: Is it still the gold standard? Periodontol 2000. 1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flotra L, Gjermo P, Rolla G, Waerhaug J. Side effects of chlorhexidine mouthwashes. Scand J Dent Res. 1971;79:119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addy M, Willis L, Moran J. The effect of toothpaste and chlorhexidine rinses on plaque accumulation during a 4-day period. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quigley GA, Hein JW. Comparative cleansing efficiency of manual and power brushing. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:26–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiremath SS. Biostatistics. In: Hiremath SS, editor. Textbook of Preventive and Community Dentistry. USA: Elsevier; 2009. p. 482. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennstrom JL. Rinsing, irrigation and sustained local delivery. In: Lang NP, Karring T, Lindhe J, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd European Workshop on Periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence Books; 1996. pp. 132–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scherer W, Gultz J, Lee SS, Kaim J. The ability of a herbal mouthrinse to reduce gingival bleeding. J Clin Dent. 1998;9:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalessi AM, Pack AR, Thomson WM, Tompkins GR. An in vivo study of the plaque control efficacy of Persica: A commercially available herbal mouthwash containing extracts of Salvadora persica. Int Dent J. 2004;54:279–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almas K, Skaug, Ahmad I. An in vitro antimicrobial comparison of miswak extract with commercially available non-alcohol mouthrinses. Int J Dental Hygiene. 2009;3:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moran J, Addy M, Roberts S. A comparison of natural product, triclosan and chlorhexidine mouthrinses on 4-day plaque regrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;19:578–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannah JJ, Johnson JD, Kuftinee MM. Long-term evaluation of toothpaste and oral rinse containing sanguinaria extract in controlling plaque and gingival inflammation and sulcular bleeding during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Maxillofac Orthopaedics. 1989;96:199–207. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopczyk RA, Abrams H, Brown AT, Matheny JL, Kaplan AL. Clinical and microscopical effects of sanguinaria-containing mouthrinse and dentifrice with and without fluoride during 6 months of use. J Periodontol. 1991;62:617–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.10.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waaler SM, Rolla G. Plaque inhibition effect of combinations of chlorhexidine with metal ions zinc and tin. Acta Odont Scand. 1980;38:213–7. doi: 10.3109/00016358009003491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]