Key Points

Efferocytosis induces macrophages to produce IL-4 and activate iNKT cells to resolve sterile inflammation.

Macrophages in mice with chronic granulomatous disease are defective in activating iNKT cells during sterile inflammation.

Abstract

Efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages following tissue injury is fundamental to the resolution of inflammation and initiation of tissue repair. Using a sterile peritonitis model in mice, we identified interleukin (IL)-4–producing efferocytosing macrophages in the peritoneum that activate invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells to produce cytokines including IL-4, IL-13, and interferon-γ. Importantly, IL-4 from macrophages contributes to alternative activation of peritoneal exudate macrophages and augments type 2 cytokine production from NKT cells to suppress inflammation. The increased peritonitis in mice deficient in IL-4, NKT cells, or IL-4Rα expression on myeloid cells suggested that each is a key component for resolution of sterile inflammation. The reduced NAD phosphate oxidase is also critical for this model, because in mice with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (X-CGD) that lack oxidase subunits, activation of iNKT cells by X-CGD peritoneal exudate macrophages was impaired during sterile peritonitis, resulting in enhanced and prolonged inflammation in these mice. Therefore, efferocytosis-induced IL-4 production and activation of IL-4–producing iNKT cells by macrophages are immunomodulatory events in an innate immune circuit required to resolve sterile inflammation and promote tissue repair.

Introduction

During an acute inflammatory response to tissue injury, neutrophils are recruited to the injury site to remove tissue debris, and clearance of apoptotic neutrophils is critical for resolution of inflammation.1 Defects in this process have been implicated in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.2-4 Phagocytosis by macrophages is the major route of neutrophil clearance,5 and this process, termed efferocytosis, has been observed following inflammation in the joint, lung, and peritoneum.5,6 After ingesting apoptotic neutrophils, efferocytosing macrophages, the macrophages that have ingested an apoptotic cell, orchestrate the resolution of inflammation by releasing anti-inflammatory molecules.7 How efferocytosing macrophages suppress sterile inflammation in vivo is unknown.

Macrophages are remarkably plastic and can differentiate into classically activated (M1) or alternatively activated (M2) subsets.8 Induction of M1 macrophages is dependent on cytokines released mainly from T-helper 1 (Th1) cells, in particular, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), in response to microbial infections. M2 macrophages that develop during tissue repair and humoral immunity against parasites or allergy, are induced by the Th2 cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13.8

IL-4 is secreted predominantly by Th2 cells, but also by other cells.9 Many biologic functions of IL-4 are mediated by signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) signaling upon ligand engagement of IL-4R.10 IL-4–activated M2 macrophages acquire many features that are beneficial for resolution of inflammation and tissue repair, including enhanced fluid-phase pinocytosis and endocytosis, enhanced phagosome proteolysis, and produce enzymes such as arginase-1 and Fizz 1 to promote the deposition of extracellular matrix and repair damaged tissues.8,11 Additionally, IL-4 decreases pro-inflammatory chemokine expression in macrophages.12 To date, there have been only a few examples in which macrophages are induced to produce IL-4.13-15

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is an inherited immunodeficiency caused by mutations in the subunits of the leukocyte NAD phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which mediates generation of reactive oxygen species by phagocytes in response to microbial pathogens.16 In addition to susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections, CGD patients often develop granulomatous inflammation, Crohn-like inflammatory bowel disease and cutaneous lesions similar to discoid lupus, all of which can be independent of infection and reflect a dysregulated inflammatory response.17 However, the underlying mechanisms for the inflammation in CGD remain incompletely understood. In this study, we define a regulatory circuit that resolves sterile immunity requiring IL-4–producing macrophages that activate invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells and that is defective in mice with X-linked CGD.

Methods

Mice

Wild-type (WT) and Il4−/− C57BL/6 mice and WT and Il44get/4get BALB/c mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). X-CGD, Cd1d−/−18 (kindly provided by L. Van Kaer, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), Jα18−/−19 (kindly provided by M. Tanuchi, RIKEN, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan) C57BL/6 mice, and I14raL/−LysMCre BALB/c mice20 were obtained from in-house colonies. Mice used in our experiments were between 8 to 12 weeks of age. All mice were maintained in specific-pathogen-free conditions, and experiments were approved by Indiana University and Washington University animal studies committees.

Sodium periodate–induced peritoneal inflammation

Each mouse was injected with 1 mL of 5 mM sodium periodate intraperitoneally. Peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Macrophages were isolated by culturing cells in a tissue culture dish for 2 hours and removing nonadherent cells.

Intracellular staining

Adherent macrophages on wells (in vitro assays) or nonadherent macrophages from peritoneal lavages were first labeled with CD115 or F4/80, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with saponin. To stain T cells, after isolation by MACS CD4 beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), mouse peritoneal CD4 T cells were ex vivo–stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for 6 hours or plate-bound anti-CD3 (4 μg/mL, 145-2C11) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL; BD PharMingen) for 24 hours, with monensin or Golgi Plug (BD Biosciences) added to cells for the final 2 hours, respectively. Cells were labeled with anti-CD4, antigen-presenting cell (APC)-conjugated PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer, and anti-TCRβ, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with saponin, and stained with anti-IL4 and anti-IFN-γ. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with either FACSCalibur or LSR II (Becton Dickinson) and results were analyzed with FlowJo (Ashland, OR).

In vitro NKT activation assay

We used 5 × 104 NKT hybridoma N38-2C12321 or N37-1A1222 cells, both kindly provided by Dr. Kyoko Hayakawa (Fox Chase Cancer Center, PA), in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium and 5% fetal bovine serum cocultured with 1 × 105 macrophages for 24 hours at 37°C.23 Supernatants were collected, and IL-2 was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For activation of splenic NKT cells, 7.5 × 104 splenic NKT cells in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium and 5% fetal bovine serum were co-cultured with 1 × 105 mouse CD1d-expressing LMTK24 cells for 48 hours. Supernatants were collected, and IL-4 and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA.

Purification and adoptive transfer of NKT cells

Splenic NKT cells from naive WT mice were purified by staining splenocytes with APC-conjugated PBS57-loaded mCD1d tetramer and isolation using anti-APC microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Isolated cells were stained with anti-CD4, anti-TCRβ, and 7AAD, and then fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS)-sorted for CD4+TCRβ+CD1d tetramer+7AAD cells. Sorted NKT cells (15 × 104 in PBS) or PBS alone were transferred via intraperitoneal injection into mice that had been challenged with sodium periodate for 66 hours. To measure cytokine production of transferred NKT cells from recipient mice, 30 hours later, peritoneal CD4 T cells were isolated and ex vivo–stimulated as described previously. All FACS sorting was done by either FACS Aria (Becton Dickinson) or Reflection sorter (iCyt, Champaign, IL).

See the supplemental data on the Blood website for additional methods (antibodies, isolation of neutrophils, induction of neutrophil apoptosis, in vitro efferocytosis assays, and quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction).

Results

Efferocytosing macrophages produce IL-4 in vitro and in vivo

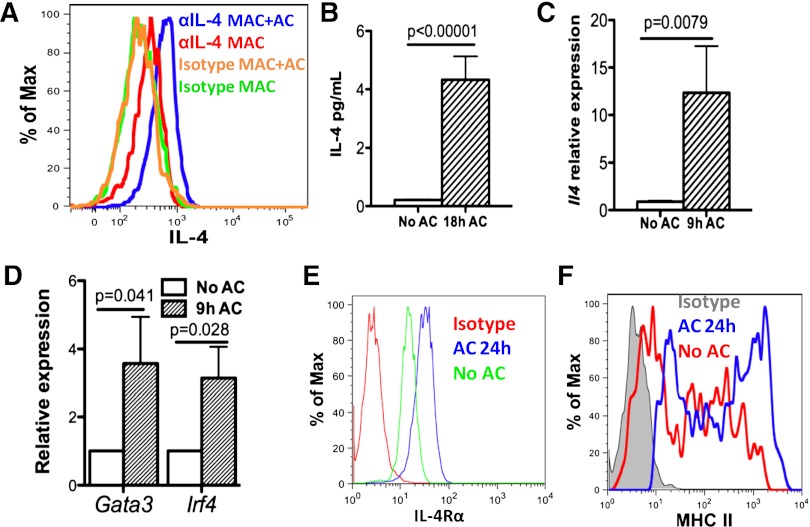

M2 macrophages8 and clearance of apoptotic neutrophils are both associated with resolution of inflammation and tissue repair. We first investigated whether efferocytosis induced macrophages to produce IL-4 following stimulation of mouse peritoneal exudate macrophages (PEM; from mice injected with sodium periodate for 3 days) with apoptotic human neutrophils (referred to as apoptotic cells or AC), which were prepared by ex vivo aging for 20 hours (supplemental Figure 1A-C). Ingestion of AC began within 30 minutes (supplemental Figure 1D-E). After 18 hours of co-culture with AC, intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) of PEM indicated production of IL-4 in PEM (Figure 1A). Low but detectable amounts of IL-4 (∼5 pg/mL per 106 cells) were detected in supernatants with AC (Figure 1B). In addition, messenger RNA for Il4 was increased 10-fold (Figure 1C), and messenger RNAs for Gata3 and Irf4, transcription factors known to induce IL-4 expression, were increased twofold in PEM after 9 hours of co-culture with AC (Figure 1D). Surface expression of IL4-responsive genes, IL-4Rα and major histocompatability complex class II (Figure 1E-F), were both increased, indicating PEM were able to respond to IL-4. Furthermore, co-culture of PEM with fixed AC (data not shown) or apoptotic mouse neutrophils induced similar responses (supplemental Figure 1F-H). Collectively, in vitro efferocytosis of apoptotic cells induced IL-4 expression in macrophages.

Figure 1.

Efferocytosing macrophages produce IL-4 in vitro. (A) WT mouse PEMs were isolated from WT B6 mice 3 days after intraperitoneal injection of sodium periodate and co-cultured with human ACs at 1:5 (mac:particle) ratio for 18 hours. IL-4 produced was determined by ICS using anti-IL-4 or isotype. F4/80 staining was used to label macrophages. (B) Amounts of IL-4 in supernatants from co-culture in (A) with ACs were measured by multiplex. (C-D) mRNA levels of Il4 (C) and the transcription factors Gata3 and Irf4 (D), in efferocytosing macrophages were measured by quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction 9 hours after co-culture with ACs. (E-F) After co-culture of PEM with ACs for 24 hours, cell surface expression of IL-4Rα and major histocompatibility complex class II were determined by antibody staining followed by flow cytometry. Data represent at least 3 independent experiments.

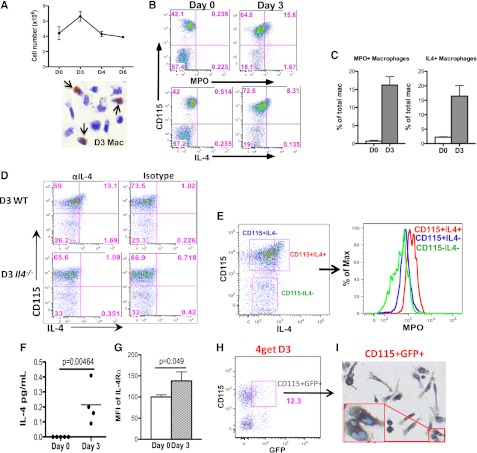

We next determined if macrophages undergoing efferocytosis in vivo produced IL-4. As a model of sterile inflammation, irritant-induced peritonitis first elicits rapid neutrophil infiltration, followed by recruitment of macrophages and efferocytosis to remove apoptotic neutrophils.5 Consistent with previous reports, peritoneal inflammation, characterized by increased inflammatory cells in the peritoneum, peaked at day 3 after injection and began to wane thereafter (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure 2A). The increased peritoneal inflammation on day 3 was also confirmed by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (supplemental Figure 2B). Diaminobenzidine histochemistry for myeloperoxidase (MPO), a neutrophil-specific granule protein, indicated the presence of neutrophils within day 3 PEM (Figure 2A). Ex vivo staining of day 3 PEM for intracellular MPO using an MPO antibody identified macrophage-colony stimulating factor receptor (M-CSFR)-+ macrophages (CD115+) that had ingested neutrophils, about 15% of total macrophages, whereas MPO-positive macrophages were rare in day 0 peritoneum (Figure 2B-C). A similar pattern was observed after ICS for IL-4 in PEM (CD115+), and staining was not observed in PEM from Il4−/− mice (Figure 2B-D and supplemental Figure 2C-D). Importantly, day 3 IL4+ PEM were also positive for MPO, thus suggesting that efferocytosing macrophages produced IL-4 in vivo (Figure 2E). Consistently, IL-4 was detectable in day 3 but not day 0 peritoneal lavages (Figure 2F), and surface IL-4Rα was higher on day 3 PEM (Figure 2G). When day 3 PEM were cultured ex vivo with anti–IL-4Rα for 48 hours, the amounts of IL-4 detected in culture supernatants were increased significantly (supplemental Figure S2E). Thus, IL-4 secreted by macrophages was being consumed by the macrophages at the same time through binding to IL-4R. IL-4 produced by efferocytosing macrophages likely stimulated PEM in an autocrine manner. To confirm Il4 expression in macrophages in vivo, we used IL-4 reporter mice (4get)25 and observed a similar percentage of GFP+ CD115+PEM in day 3 (Figure 2H) but not day 0 mice (data not shown). Importantly, diaminobenzidine histochemistry for MPO revealed staining in nearly all sorted GFP+CD115+ cells (Figure 2I), but only about 10% of total macrophages (data not shown), again confirming these IL-4–producing macrophages had ingested neutrophils. Overall, our data demonstrate the emergence of IL-4–producing efferocytosing macrophages during sterile inflammation.

Figure 2.

Efferocytosing macrophages produce IL-4 in vivo. (A) Peritoneal cell counts on day 0, 3, 4, or 6 following intraperitoneal injection of sodium periodate were enumerated and graphed. Immediately after peritoneal lavage, day 3 PEM with ingested neutrophils (arrows) were identified by cytospin and diaminobenzidine histochemical staining for MPO. (B) Day 0 or day 3 peritoneal cells were first labeled with CD115 and then stained for MPO and IL-4. Percentages of MPO-positive or IL-4–positive macrophages were quantified in (C). (D) PEM from day 3 WT or Il4−/− mice were labeled with CD115 and stained for intracellular IL-4 using anti-IL-4 or isotype. (E) MPO within CD115+IL-4+, CD115+IL-4, and CD115-IL-4 populations in day 3 peritoneal cells were measured by anti-MPO and compared by histogram (right). (F) Amounts of IL-4 in peritoneal lavages from naive mice or day 3 mice were measured by multiplex. Three to 4 mice were used for each time point. (G) Surface IL-4Rα chain on day 0 and day 3 macrophages were compared by flow cytometry. (H) Day 3 peritoneal cells from a 4get BALB/c mouse were labeled with CD115. GFP+CD115+ cells were sorted by FACS and followed by diaminobenzidine histochemistry for MPO on a microscope slide. (I) The sorted cells were then imaged; brown staining indicated the presence of MPO within the cells. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

iNKT cells in inflamed peritoneum produced cytokines during the resolution of inflammation

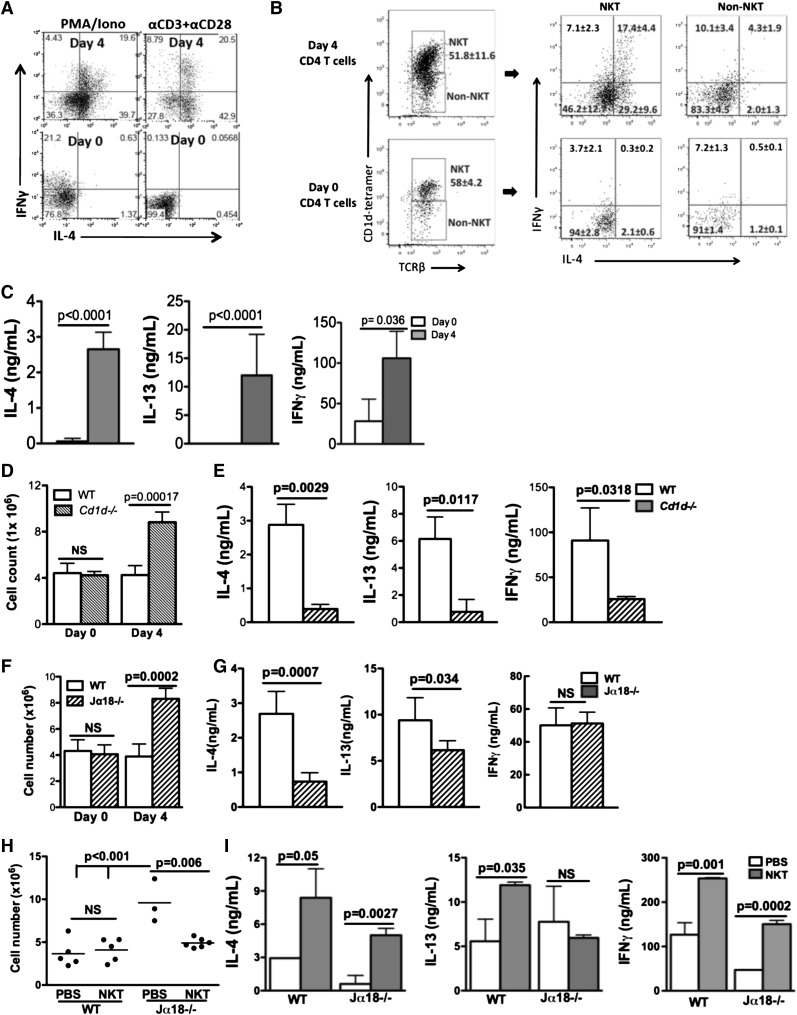

To examine whether there were IL-4–producing T cells during resolution of sterile inflammation, we stimulated peritoneal exudate CD4 T cells with PMA and ionomycin or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 and analyzed cytokine production. IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ were produced by day 4 CD4 T cells but not day 0 or day 3 (Figure 3A-C; data not shown). ICS indicated that more than half of day 4 CD4 T cells produced IL-4. The rapid emergence of an activated population of CD4 T cells producing both Th1 and Th2 cytokines suggested an innate response. Thus, we next determined whether these activated CD4 T cells were NKT cells, a subset of CD4 T cells known to rapidly produce a variety of cytokines upon activation. Indeed, both day 0 and day 4 CD4 T cells contained up to 50% NKT cells (CD1d tetramer+TCRβ+). Additionally, IL-4 and IFN-γ production were found almost exclusively in the day 4 NKT population (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

iNKT cells in inflamed peritoneum produced cytokines during the resolution of inflammation. (A) Day 0 or day 4 WT CD4 T cells were ex vivo–stimulated by PMA/ionomycin (Iono) or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, and stained for intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ. (B) Following stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 hours, day 0 or day 4 CD4 T cells were gated into NKT (CD1d tetramer+ TCRβ +) and non-NKT (CD1d tetramer-TCRβ +) populations. Each population was assessed for intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ. (C) IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ in supernatants after anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation were measured by ELISA. (D-G) Peritonitis was induced by sodium periodate injection in WT and Cd1d−/− or Jα18−/− mice. Inflammation was assessed by peritoneal cell counts (D, F). IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ in supernatants of Cd1d−/− (E) or Jα18−/− mice (G) day 4 CD4 T cells after anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation were measured by ELISA. (H) WT splenic NKT cells or PBS were adoptively transferred into WT or Jα18−/− mice at 66 hours after sodium periodate injection. Peritoneal inflammation was scored by cell counts 30 hours later. (I) CD4 T cells from recipient mice in (H) were stimulated ex vivo for 48 hours, and IL-4 and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA. Data represent at least 2 independent experiments.

To assess the importance of NKT cells, we evaluated peritonitis in Cd1d−/− mice.18 Peritoneal leukocyte numbers remained elevated in Cd1d−/− mice (Figure 3D). In addition, day 4 Cd1d−/− CD4 T cells produced minimal IL-4 and IL-13 after ex vivo stimulation, and only ∼25% of the amounts of IFN-γ produced by CD4 T cells from day 4 WT mice (Figure 3E), consistent with NKT cells being the main CD4 population producing these cytokines on day 4.

Because Cd1d−/− mice lack both type I (invariant) and type II (noninvariant) NKT cells, we examined Jα18−/− mice,19,26 which lack only iNKT cells, to identify the type of NKT cells critical to suppress the inflammation. The inflammation was more profound in day 4 Jα18−/− mice compared with WT controls (Figure 3F). Amounts of IFN-γ produced by ex vivo–stimulated CD4 T cells from day 4 Jα18−/− mice appeared normal. In contrast, IL-4 and IL-13 production by day 4 Jα18−/− CD4 T cells was reduced by almost 70% and ∼30%, respectively, relative to WT controls (Figure 3G). The substantial decrease in IL-4 production by Jα18−/− CD4 T cells suggested that iNKT cells were the major CD4 T cells producing IL-4, and the diminished IL-4 may contribute to the increased inflammation in these mice.

To confirm that the absence of iNKT cells in Jα18−/− mice accounted for the exaggerated inflammation in these mice, we adoptively transferred WT splenic NKT cells (supplemental Figure 3A) or injected PBS into WT or Jα18−/− mice 66 hours after injection of periodate. Thirty hours later, inflammation in Jα18−/− NKT recipients was reduced significantly compared with the Jα18−/− mice that received PBS, similar to WT recipient groups (Figure 3H). Ex vivo–stimulated CD4 T cells from Jα18−/− NKT recipients produced more IL-4 and IFN-γ compared with Jα18−/− PBS recipients; a similar increase was observed in WT NKT cell recipients (Figure 3I). Adoptive transfer of WT NKT cells was unable to rescue Cd1d−/− mice, suggesting CD1d-mediated NKT cell activation, not simply the presence of NKT cells, was required for resolution of inflammation (supplemental Figure 3B-C).

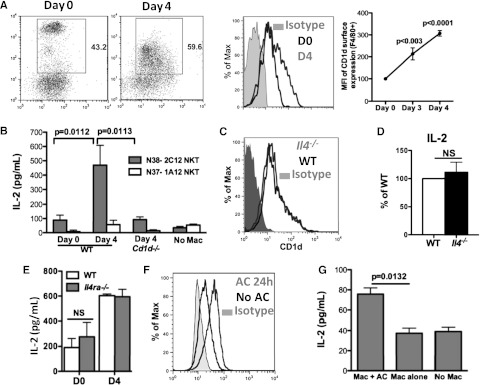

Efferocytosing macrophages increased CD1d expression and activate iNKT cells

Activation of NKT cells requires CD1d-dependent presentation of lipid antigens.27 Notably, cytokine secretion by peritoneal NKT cells appeared to be more dependent on activation by APC than thymic NKT cells (supplemental Figure 4A). Macrophages, the predominant APC in the peritoneum, might be the likely candidate to activate NKT cells. Cell surface expression of CD1d on day 3 and day 4 PEM during inflammation was increased compared with day 0 macrophages (Figure 4A). Next, to assess whether exudate macrophages were able to activate NKT cells, we co-cultured either day 0 or day 4 macrophages with either the type I mouse NKT hybridoma N38-2C12 or the type II mouse NKT hybridoma N37-1A12. Activation of N38-2C12 NKT cells, as assayed by production of IL-2, was induced by day 4 PEM but not day 0 macrophages and was dependent on CD1d on macrophages (Figure 4B). In addition, day 0 macrophages and day 3 PEM displayed a difference stimulating IL-4 production by splenic NKT cells (supplemental Figure 4B). This demonstrated that peritoneal inflammatory macrophages were more competent than resident macrophages to activate iNKT cells. IL-4 was not required for macrophages to activate NKT cells because Il4−/− and Il4ra−/− macrophages displayed normal surface CD1d and induction of IL-2 by N38-2C12 NKT cells (Figure 4C-E).

Figure 4.

Efferocytosing macrophages increased CD1d expression and activate iNKT cells. (A) Day 0, day 3, and day 4 peritoneal macrophages (F4/80+) were assessed for surface expression of CD1d, and mean fluorescence intensity was compared. Data represent at least 3 independent experiments. (B) Activation of N38-2C12 or N37-1A12 NKT cells by day 0 or day 4 peritoneal macrophages was determined by measuring IL-2 production by the NKT cells 24 hours after co-culture. Data represent at least 3 independent experiments. (C-D) Day 4 WT and Il4−/− peritoneal macrophages were assessed for surface expression of CD1d (C) and their ability to activate N38-2C12 NKT cells to produce IL-2 (D). Data represent 2 independent experiments. (E) Day 0 and day 4 WT and Il4ra−/− macrophages were co-cultured with N38-2C12 NKT cells and IL-2 from culture media were measured as in (B). Data represent 2 independent experiments. (F) Day 3 peritoneal exudate macrophages were co-cultured with apoptotic mouse neutrophils for 24 hours, and surface expression of CD1d on these macrophages was compared with that on macrophages without AC. (G) Macrophages from (F) were used to co-culture with N38-NKT cells and IL-2 in supernatants was measured by ELISA. Data represent 3 independent experiments.

We next tested whether in vitro efferocytosis induces PEM to be competent for NKT cell activation. CD1d expression was increased on macrophages co-cultured with mouse AC compared with macrophages not exposed to AC (Figure 4F). Moreover, only macrophages co-cultured with AC were able to activate NKT hybridomas (Figure 4G). This observation suggests that subsequent to efferocytosis, macrophages become capable of activating type I NKT cells, at least partially via increased surface CD1d.

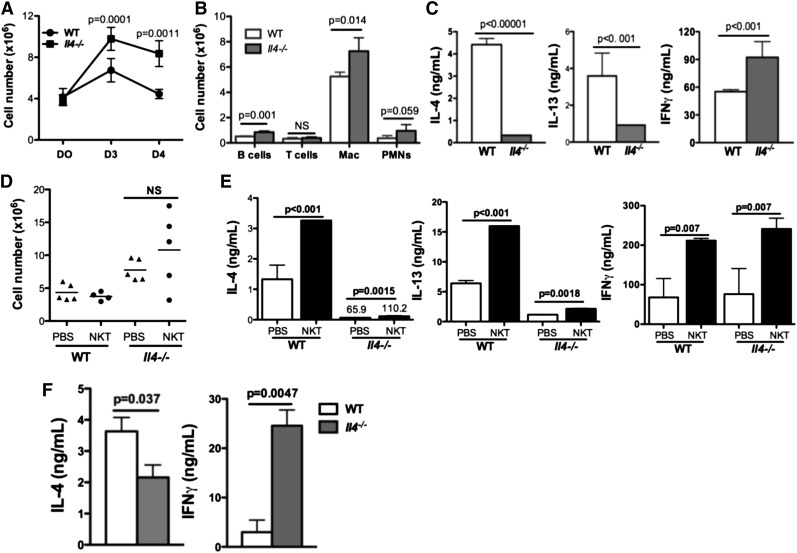

Mice lacking IL-4 displayed impaired resolution of sterile inflammation

We next assessed the importance of IL-4 in this model. After periodate challenge, peritoneal leukocytes remained elevated in Il4−/− mice compared with WT mice on days 3 and 4 (Figure 5A-B). Additionally, macrophages (not shown) and CD4 T cells from day 4 Il4−/− mice produced no IL-4, as expected, and minimal levels of IL-13, but higher levels of IFN-γ compared with WT controls (Figure 5C). Adoptive transfer of WT splenic NKT cells into Il4−/− mice did not ameliorate inflammation in these mice, suggesting that NKT cells are not the only relevant IL-4–producing population (Figure 5D). We observed minimal IL-4 or IL-13 production by CD4 T cells isolated from the Il4−/− mice that received WT NKT cells despite more IFN-γ production (Figure 5E). Thus, the transferred NKT cells were activated in Il4−/− mice, but unable to produce IL-4 or IL-13. We speculated that although in vivo Il4−/− PEM might be able to activate NKT cells, without IL-4 from Il4−/− PEM, cytokine production from transferred NKT cells might be altered. To test this, we co-cultured day 3 WT or Il4−/− PEM with splenic NKT cells for 48 hours and observed less IL-4 but more IFN-γ production (Figure 5F). Exogenous IL-4 added to the co-culture media was able to increase IL-4 production by NKT cells (supplemental Figure 5A). Similarly, exogenous IL-4 resulted in an increase in IL-4–producing splenic NKT cells (supplemental Figure 5B). Therefore, IL-4 production from efferocytosing macrophages has an essential role in the resolution of inflammation, perhaps in part by augmenting IL-4 production from NKT cells (supplemental Figure 6D).

Figure 5.

Mice lacking IL-4 displayed impaired resolution of sterile inflammation. (A) Inflammation induced by sodium periodate in Il4−/− and WT mice was scored by determining cell counts at day 0, day 3, and day 4. (B) Cell populations were compared between Il4−/− and WT mice on day 3. (C) Peritoneal CD4 T cells isolated from day 4 Il4−/− or WT mice were ex vivo–stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 for 24 hours. IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ in supernatants were measured by ELISA. (D) WT splenic NKT cells were adoptively transferred into WT or Il4−/− mice 66 hours after intraperitoneal injection of sodium periodate; peritoneal cell numbers in recipient mice were enumerated as described in Figure 3H. (E) CD4+ T cells isolated from recipient mice in (D) were stimulated and cytokine profile was examined as in Figure 3I. (F) WT or Il4−/− day 3 PEM were co-cultured with WT splenic NKT cells for 48 hours before IL-4 and IFN-γ in supernatants were measured by ELISA. PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

IL-4 signaling in macrophages promotes an M2 phenotype important for the resolution of inflammation

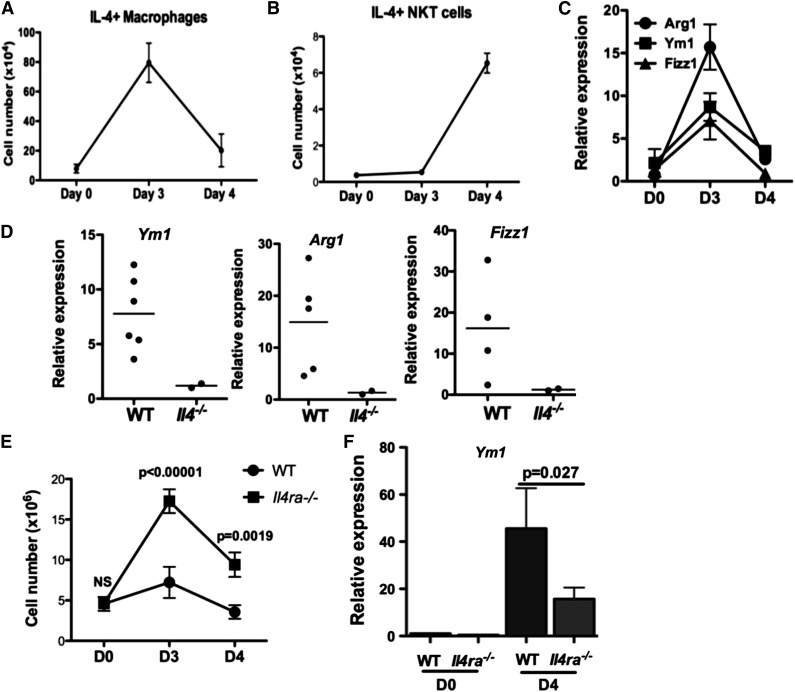

Our results indicated a temporal difference in IL-4 production by 2 cell types in the inflamed peritoneum: efferocytosing macrophages peaking on day 3 and iNKT cells on day 4 (Figure 6A-B). We observed elevated expression of M2 markers Arg1, Ym1, and Fizz1 in PEM (Figure 6C), which depended on IL-4 (Figure 6D). Notably, the expression of these markers peaked on day 3, coinciding with IL-4 production by efferocytosing macrophages in the peritoneum. Thus, another function of IL-4 from macrophages in this model may be to promote the M2 phenotype.

Figure 6.

IL-4 signaling in macrophages promotes an M2 phenotype important for the resolution of inflammation. (A-B) The number of IL-4–producing macrophages (A) or NKT cells (B) during the course of peritonitis in WT mice was determined by ICS and flow cytometry. At least 3 mice were examined for each time point. (C) Peritoneal macrophages were cultured ex vivo for 48 hours, and expression of M2 markers Arg1, Ym1, and Fizz1 were quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data represent 2 independent experiments. (D) Expression of M2 markers in day 3 WT and Il4−/− peritoneal macrophages were determined and compared as described in (C). Each dot represents data from 1 mouse. (E) Severity of sodium periodate–induced peritonitis in WT or I14raL/−LysMCre mice was scored by enumeration of peritoneal cells at days 0, 3, and 4. (F) Expression of Ym1 in mice from (E) was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

To identify cellular targets of IL-4 to suppress inflammation, we induced peritonitis in I14raL/-LysMCre BALB/c mice in which myeloid cells were unable to respond to IL-4 because of deletion of IL-4Rα. Peritoneal inflammation in I14raL/−LysMCre mice was significantly enhanced compared with WT BALB/c mice (Figure 6E). Efferocytosing macrophages in I14raL/−LysMCre mice were capable of making IL-4, and MPO+ and IL4+ peritoneal macrophages in I14raL/−LysMCre mice appeared comparable to WT controls (supplemental Figure 6A-B). Although expression of Arg1 and Fizz1 was not altered by inflammation in WT BALB/c mice (data not shown), induction of Ym1 was attenuated in I14raL/−LysMCre PEM, compared with WT PEM (Fig. 6F). Importantly, activation of NKT cells in I14raL/−LysMCre mice was not affected by the deletion of IL-4 responses in macrophages (supplemental Figure 6C). Activated NKT cells were detected on day 3 and day 4 in BALB/c mice (supplemental Figure 6C), but only detected on day 4 in B6 mice (Figure 6B). Together, our data supported that myeloid cells, likely macrophages, are critical targets for IL-4 to mediate suppression of inflammation, and that this requirement is independent of iNKT activation.

X-CGD mice had enhanced peritoneal inflammation and delayed resolution

We next investigated the efferocytosing macrophage-iNKT cell circuit during sterile peritoneal inflammation in mice with CGD, which are impaired in resolving sterile inflammation.28-30 We observed that periodate challenge led to more exaggerated and prolonged peritoneal inflammation in mice lacking gp91phox, referred to as X-CGD mice (Figure 7A). There was no difference in the fraction of X-CGD PEM ingesting AC, either in vivo or in vitro, compared to WT PEM (supplemental Figure 7A-B). In association with the elevated numbers of infiltrated neutrophils initially at 8 hours and later more exudate macrophages in X-CGD mice on day 3 (Figure 7B), there were more MPO-positive and IL-4–producing macrophages recovered from the peritoneum of X-CGD mice on day 3 compared with WT mice (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Impaired activation of peritoneal NKT cells partially contributed to the enhanced peritoneal inflammation and delayed resolution in mice with X-CGD. (A) Total peritoneal cell counts in X-CGD and WT mice were determined at day 0, 8 hours, and days 3, 4, and 6 after intraperitoneal (IP) injection. (B, left) The number of neutrophils (GR1high) in the peritoneal cavities of WT or X-CGD mice at baseline and 8 hours after IP injection of sodium periodate was determined by flow cytometry. (Right) Absolute cell numbers of macrophages (F4/80+), granulocytes (GR1high), T cells (CD3+), and B cells (B220+) in the peritoneal cavities of WT or X-CGD mice at baseline and 8 hours after IP injection of sodium periodate was determined by flow cytometry. (C) The numbers of MPO+ (E) or IL-4+ (F) PEMs were determined by ICS in X-CGD and WT mice at day 0 and day 3. At least 3 mice were used for each genotype at each time point. Data represent at least 3 experiments. (D) NKT (CD1d tetramer+ TCRβ +) or non-NKT (CD1d tetramer- TCRβ +) populations from day 4 WT or X-CGD peritoneum were identified as described in Figure 3. Each population was assessed for intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ. (E) Day 0 or day 4 WT and X-CGD CD4 T cells were ex vivo–stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 hours; IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ in supernatants were measured by ELISA. (F) Day 0 and day 4 WT or X-CGD PEM were assessed for surface expression of CD1d by flow cytometry, and mean fluorescence intensity is shown. (G) Activation of N38-2C12 NKT cells by day 4 WT or X-CGD PEMs was determined by measuring IL-2 production by the NKT cells 24 hours after co-culture with the macrophages. (H) Adoptive transfer of WT splenic NKT cells into either WT or X-CGD mice after induction of peritonitis was performed as described in Figure 3. Day 4 peritoneal cell counts were determined. (I) CD4 T cells from recipient mice were ex vivo–stimulated as described in Figure 3, and IL-4 and IFN-γ production were measured by ELISA. (J) WT or X-CGD splenic NKT cells were co-cultured with mCD1d-expressing LMTK cells ex vivo for 48 hours, and IL-4 and IFN-γ production were measured by ELISA. All data represent 2 to 3 independent experiments. PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Because the production of IL-4 by macrophages was not impaired in X-CGD mice, we next examined NKT cell function in these mice. The percentage of peritoneal NKT cells in the CD4 T cell population in X-CGD mice was similar to that in WT mice (Figure 7D). However, fewer X-CGD NKT cells produced IL-4, but more produced IFN-γ compared with WT NKT cells (Figure 7D). Cytokine analysis by ELISA after ex vivo stimulation of peritoneal exudate CD4 T cells was consistent and also revealed decreased IL-13 production (Figure 7E). Additionally, day 4 X-CGD PEM showed reduced surface CD1d and induced only minimal IL-2 production by N38-2C12 NKT cells in vitro (Figure 7G), thus suggesting a defect in the activation of iNKT cells by X-CGD PEM.

To demonstrate a defect in activation of NKT cells by X-CGD PEM, we adoptively transferred WT splenic NKT cells into X-CGD mice. Inflammation in X-CGD NKT recipients was not ameliorated and there were only modest changes in IL-4 and IFN-γ production by CD4 T cells isolated from these mice compared with PBS controls, in contrast to results in WT recipients (Figure 7H-I). To delineate whether there was an intrinsic defect in X-CGD NKT cells contributing to their reduced activation, we activated WT or X-CGD splenic NKT cells ex vivo with CD1d-expressng LMTK cells. X-CGD splenic NKT cells produced about 50% and 30% less IL-4 and IFN-γ, respectively, compared with WT splenic NKT cells (Figure 7J), demonstrating a partial intrinsic defect in activation of X-CGD NKT cells. Therefore, our data support a role for the NADPH-oxidase in macrophages to activate NKT cells, in the ability X-CGD NKT cells to be activated, and that both of these defects contribute to exaggerated and prolonged inflammation in X-CGD mice.

Discussion

Macrophage efferocytosis of apoptotic cells induces many responses to suppress inflammation. In this study, we demonstrate a novel cellular circuit involving 3 innate cell types required to resolve sterile inflammation (supplemental Figure 6D). Upon ingesting apoptotic neutrophils, macrophages produce IL-4, increase CD1d expression, and activate iNKT cells that produce IL-4. Macrophage-derived IL-4 has autocrine effects on M2 development and paracrine effects on IL-4 production by NKT cells.

IL-4 from both macrophages and iNKT cells, and IL-4Rα–mediated acquisition of M2 characteristics all are required for prompt resolution of sterile inflammation. Both the ability of macrophages to activate NKT cells and cytokine production from NKT cells are impaired in X-CGD mice. Thus, efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages initiates the activation of iNKT cells and IL-4 production that contribute to the resolution of sterile inflammation.

The crucial role of M2 macrophages in resolution of inflammation, tissue repair, and homeostasis is well documented.31 Although alternative activation of macrophages has been largely attributed to IL-4 and IL-13 from Th2 lymphocytes, potential sources of IL-4 during acute sterile inflammation have not been investigated. Our observation of IL-4 production in efferocytosing macrophages revealed autocrine IL-4 production by macrophages that promoted M2 characteristics. Although the amounts of IL-4 secreted by macrophages are modest, our observations are consistent with previous studies of IL-4 production by dendritic cells that postulated autocrine IL-4 binding as being responsible for this discrepancy.32,33 IL-4 from efferocytosing macrophages might be an initial source of IL-4 to skew macrophages toward the M2 phenotype to promote digestion of damaged tissue and tissue repair before activation of IL-4 production by other cell types. Efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils and the recruitment and induction of M2 macrophages are crucial early events necessary for wound healing. Our study establishes a link between these 2 events.

Our data demonstrated an important role for the macrophage-iNKT cell circuit in resolving sterile inflammation. The essential role of CD1d-dependent stimulation of NKT cells to resolve sterile inflammation was highlighted by the ability of adoptively transferred WT NKT cells to rescue Jα18−/− but not Cd1d−/− mice. In addition, the exaggerated inflammation in Il4−/− mice reflects a requirement for IL-4 from efferocytosing macrophages and NKT cells. Subsequently, by the enhanced inflammation in Jα18−/− mice and the failure of transferred WT NKT cells to rescue Il4−/− mice, we demonstrated the importance of both IL-4 from iNKT cells and macrophages in mediating the resolution of inflammation, respectively.

NKT cells are involved in responses to viral infections, autoimmune diseases, and tumor rejection.34,35 Although counterregulation by type I and type II NKT cells has been observed,36,37 the inability of Cd1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice to promptly resolve the inflammation supported a more essential role for type I NKT cells in our model. Our data also suggested IL-4 from efferocytosing macrophages or exogenous IL-4 enhances IL-4 production in NKT cells. Activation of NKT cells requires presentations of lipid antigens via CD1d by APC, but additional signals are likely necessary to promote Th1-like or Th2-like responses from NKT cells.21 For example, IFN-γ production by α-GalCer–stimulated NKT cells is mainly dependent on IL-12 from DC.38 Therefore, IL-4 producing efferocytosing macrophages may represent a type of in vivo APC capable of both activating and altering the cytokine response of iNKT cells.

Defective inflammatory responses in the absence of NADPH oxidase-generated oxidants have been identified in CGD patients and mice.17 In contrast to a report of defective efferocytosis by CGD macrophages,39 our in vitro and in vivo studies revealed a similar capacity for efferocytosis by CGD macrophages. The discrepancy may be due to the differences in the types of ACs used and how ACs were prepared. In our study, X-CGD mice had elevated numbers of peritoneal neutrophils in response to tissue injury and subsequently a prolonged increase in the number of macrophages, including those ingesting neutrophils and producing IL-4 and IL-13. The presence of these cytokine-producing macrophages is insufficient to suppress inflammation in these mice, and their prolonged presence may in fact contribute to sustained inflammation, as seen in chronic Th2-dependent airway inflammation.40 We also showed defective activation of iNKT cells in X-CGD mice during sterile inflammation and delineated 2 contributory factors: an impairment in CD1d-dependent antigen presentation by X-CGD macrophages and an intrinsic defect in cytokine production from X-CGD NKT cells. The phagocyte NADPH oxidase has been linked to phagosome maturation and processing of ingested particles.41,42 Conversely, oxidants derived from the NADPH oxidase may modulate the processing of ingested AC and subsequent interaction with iNKT cells, because we also found that ingestion of AC activates the NADPH oxidase in WT macrophages (unpublished data). The intrinsic defect we observed in X-CGD NKT cells is intriguing and suggests that NKT cells may have a functional oxidase and its possible engagement during NKT cell activation. Of note, expression of NADPH oxidase and its activation after T-cell receptor stimulation was observed in T cells43 and dysregulated T-cell responses were reported in X-CGD mice.44 The difficulty of resolving inflammation in the absence of infection is a hallmark of CGD. Therefore, defective activation of NKT cells during inflammation might contribute to the pathology of CGD.

The IL-4–dependent macrophage-iNKT cell circuit may be 1 suppressive component of AC clearance in the resolution of sterile inflammation. The clearance of AC is not as “silent” as once viewed; rather, it elicits various immune responses. For example, dendritic cells that have engulfed apoptotic tumor or virus-infected cells can cross-present antigens from AC to cytotoxic T cells.45-47 Infected AC may direct Th17 differentiation by inducing IL-6 production by dendritic cells.48 In a potentially parallel mechanism to our work, iNKT cells were recently demonstrated to mediate the anti-inflammatory effects of AC by limiting autoreactive responses by CD1d+ B cells.49 Therefore, efferocytosis-induced activation of iNKT cells may be a mechanism for iNKT cell activation to suppress autoreactivity that could be otherwise induced by AC. It is noteworthy that discoid lupus has been reported in X-CGD patients and carriers.50 Thus, modulating iNKT cell function from the perspective of macrophage efferocytosis could be explored further to address the inflammation and possible enhanced autoimmune response arising in patients with CGD and lupus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Blum for suggestions and review of this article, J. Jones for help with NKT-deficient mice, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Tetramer Facility for CD1d tetramers.

This work was supported by NIH grants (R01 AI045515, R01 AI057459 to M.H.K., R01 HL45635 (to M.C.D.), and R01 AI46455 (to R.R.B.), and from the Children’s Discovery Institute at Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital (M.C.D.). M.Y.Z was supported by NIH grant T32 AI060519. D.P. was supported by NIH grant T32 HL07910 to Indiana University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.Y.Z, M.H.K., and M.C.D. designed all experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.Y.Z. performed experiments; D.P., J.B., J.L., K.O., and M.S. helped with experiments; and R.R.B., F.B., and T.A.W. provided key reagents.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary C. Dinauer, Department of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: dinauer_m@kids.wustl.edu.

References

- 1.Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(12):965–975. doi: 10.1038/nri957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erwig LP, Henson PM. Immunological consequences of apoptotic cell phagocytosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(1):2–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch X. Systemic lupus erythematosus and the neutrophil. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):758–760. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1107085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(73):73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savill JS, Wyllie AH, Henson JE, Walport MJ, Henson PM, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. Programmed cell death in the neutrophil leads to its recognition by macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(3):865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanui H, Yoshida S, Nomoto K, Ohhara R, Adachi Y. Peritoneal macrophages which phagocytose autologous polymorphonuclear leucocytes in guinea-pigs. I: induction by irritants and microorgansisms and inhibition by colchicine. Br J Exp Pathol. 1982;63(3):278–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(4):890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32(5):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(4):225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goenka S, Kaplan MH. Transcriptional regulation by STAT6. Immunol Res. 2011;50(1):87–96. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loke P, Gallagher I, Nair MG, et al. Alternative activation is an innate response to injury that requires CD4+ T cells to be sustained during chronic infection. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):3926–3936. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loke P, Nair MG, Parkinson J, Guiliano D, Blaxter M, Allen JE. IL-4 dependent alternatively-activated macrophages have a distinctive in vivo gene expression phenotype. BMC Immunol. 2002;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirey KA, Pletneva LM, Puche AC, et al. Control of RSV-induced lung injury by alternatively activated macrophages is IL-4R alpha-, TLR4-, and IFN-beta-dependent. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3(3):291–300. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee S, Chen LY, Papadimos TJ, Huang S, Zuraw BL, Pan ZK. Lipopolysaccharide-driven Th2 cytokine production in macrophages is regulated by both MyD88 and TRAM. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(43):29391–29398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirey KA, Cole LE, Keegan AD, Vogel SN. Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain induces macrophage alternative activation as a survival mechanism. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4159–4167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinauer MC. Chronic granulomatous disease and other disorders of phagocyte function. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005;1:89–95. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schäppi MG, Jaquet V, Belli DC, Krause KH. Hyperinflammation in chronic granulomatous disease and anti-inflammatory role of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30(3):255–271. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendiratta SK, Martin WD, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6(4):469–477. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, et al. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278(5343):1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert DR, Hölscher C, Mohrs M, et al. Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity. 2004;20(5):623–635. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gui M, Li J, Wen LJ, Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. TCR beta chain influences but does not solely control autoreactivity of V alpha 14J281T cells. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6239–6246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burdin N, Brossay L, Koezuka Y, et al. Selective ability of mouse CD1 to present glycolipids: alpha-galactosylceramide specifically stimulates V alpha 14+ NK T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161(7):3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts TJ, Sriram V, Spence PM, et al. Recycling CD1d1 molecules present endogenous antigens processed in an endocytic compartment to NKT cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(11):5409–5414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, Paul WE. Cultured NK1.1+ CD4+ T cells produce large amounts of IL-4 and IFN-gamma upon activation by anti-CD3 or CD1. J Immunol. 1997;159(5):2240–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohrs M, Shinkai K, Mohrs K, Locksley RM. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity. 2001;15(2):303–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278(5343):1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brutkiewicz RR. CD1d ligands: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Immunol. 2006;177(2):769–775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson SH, Gallin JI, Holland SM. The p47phox mouse knock-out model of chronic granulomatous disease. J Exp Med. 1995;182(3):751–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Boyanapalli R, Frasch SC, Riches DW, Vandivier RW, Henson PM, Bratton DL. PPARγ activation normalizes resolution of acute sterile inflammation in murine chronic granulomatous disease. Blood. 2010;116(22):4512–4522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-272005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollock JD, Williams DA, Gifford MA, et al. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat Genet. 1995;9(2):202–209. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karp CL, Murray PJ. Non-canonical alternatives: what a macrophage is 4. J Exp Med. 2012;209(3):427–431. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelleher P, Maroof A, Knight SC. Retrovirally induced switch from production of IL-12 to IL-4 in dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(7):2309–2318. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2309::AID-IMMU2309>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maroof A, Penny M, Kingston R, et al. Interleukin-4 can induce interleukin-4 production in dendritic cells. Immunology. 2006;117(2):271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. NKT cells in tumor immunity: opposing subsets define a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2008;180(6):3627–3635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grajewski RS, Hansen AM, Agarwal RK, et al. Activation of invariant NKT cells ameliorates experimental ocular autoimmunity by a mechanism involving innate IFN-gamma production and dampening of the adaptive Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):4791–4797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, et al. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5126–5136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halder RC, Aguilera C, Maricic I, Kumar V. Type II NKT cell-mediated anergy induction in type I NKT cells prevents inflammatory liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2302–2312. doi: 10.1172/JCI31602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189(7):1121–1128. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez-Boyanapalli RF, Frasch SC, McPhillips K, et al. Impaired apoptotic cell clearance in CGD due to altered macrophage programming is reversed by phosphatidylserine-dependent production of IL-4. Blood. 2009;113(9):2047–2055. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bosnjak B, Stelzmueller B, Erb KJ, Epstein MM. Treatment of allergic asthma: modulation of Th2 cells and their responses. Respir Res. 2011;12:114. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantegazza AR, Savina A, Vermeulen M, et al. NADPH oxidase controls phagosomal pH and antigen cross-presentation in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112(12):4712–4722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savina A, Peres A, Cebrian I, et al. The small GTPase Rac2 controls phagosomal alkalinization and antigen crosspresentation selectively in CD8(+) dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;30(4):544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson SH, Devadas S, Kwon J, Pinto LA, Williams MS. T cells express a phagocyte-type NADPH oxidase that is activated after T cell receptor stimulation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(8):818–827. doi: 10.1038/ni1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romani L, Fallarino F, De Luca A, et al. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature. 2008;451(7175):211–215. doi: 10.1038/nature06471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonmort M, Dalod M, Mignot G, Ullrich E, Chaput N, Zitvogel L. Killer dendritic cells: IKDC and the others. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(5):558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albert ML, Pearce SF, Francisco LM, et al. Immature dendritic cells phagocytose apoptotic cells via alphavbeta5 and CD36, and cross-present antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;188(7):1359–1368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albert ML, Sauter B, Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cells acquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature. 1998;392(6671):86–89. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM. Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;458(7234):78–82. doi: 10.1038/nature07781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wermeling F, Lind SM, Jordö ED, Cardell SL, Karlsson MC. Invariant NKT cells limit activation of autoreactive CD1d-positive B cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207(5):943–952. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Ravin SS, Naumann N, Cowen EW, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease as a risk factor for autoimmune disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(6):1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.