Abstract

Purpose

To compare vitreous biopsy methods using analysis platforms employed in proteomics biomarker discovery.

Methods

Vitreous biopsies from 10 eyes were collected sequentially using a 23-gauge needle and a 23-gauge vitreous cutter instrument. Paired specimens were evaluated by UV absorbance spectroscopy, SDS-PAGE, and mass-spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Results

The total protein concentration obtained with a needle and vitrectomy instrument biopsy averaged 1.10 mg/ml (SEM = 0.35) and 1.13 mg/ml (SEM = 0.25), respectively. In eight eyes with low or medium viscidity, there was a very high correlation (R2 = 0.934) between the biopsy methods. When data from two eyes with high viscidity vitreous were included, the correlation was reduced (R2 = 0.704). The molecular weight protein SDS-PAGE profiles of paired needle and vitreous cutter samples were similar, except for a minority of pairs with single band intensity variance. Using LC-MS/MS, equivalent peptides were identified with similar frequencies (R2 ≥ 0.90) in paired samples.

Conclusion

Proteins and peptides collected from vitreous needle biopsies are nearly equivalent to those obtained from a vitreous cutter instrument. This study suggests both techniques may be used for most proteomic and biomarker discovery studies of vitreoretinal diseases, although a minority of proteins and peptides may differ in concentration.

Introduction

The vitreous gel is an optically transparent extracellular matrix that normally displays a graded density at different anatomical locations.1, 2 Although it is estimated to be nearly 90% water, the vitreous gel contains diverse proteins, proteoglycans, and small molecules that originate from within and outside the eye. In specific vitreoretinal diseases, the gel composition changes and some proteins may be differentially expressed.3–5 With alterations in vitreous proteins and constituents, the vitreous gel can change from a normally low to high viscidity, which describes a change in thickness, viscosity, or “stickiness” of a liquid tissue, or an elevation of its spinnability (spinnbarkeit). This is clinically recognized during intraocular surgery when the density of vitreous slows the flow characteristics during vitrectomy and changes in the optical index gradient between moving laminar high and low density fluids, which may be evident as schlieren.6,7 Understanding the molecular basis associated with clinical changes to the vitreous gel may help determine some of the underlying mechanisms of vitreoretinal diseases.

Proteomic analytical methods are used to identify biomarkers and molecular changes associated with changes in physiologic conditions or specific disease mechanisms.8 Recent advances in proteomic research facilitate the identification and quantification of the library of proteins present in the vitreous of diseased eyes. 4, 5 However, proteomic analyses are expensive and pilot studies are needed to establish optimum comparative techniques that may be used in larger clinical studies. Vitreous biopsies are frequently utilized in the clinical diagnosis and management of intravitreal infection, inflammation, and cancer. 9–11 Vitreous biopsies are routinely obtained by one of two different methods. In the most common and least invasive method, a needle is inserted through the pars plana into the vitreous cavity, and fluid is manually aspirated into a syringe. Since the instrumentation is simple and the procedure straightforward, needle biopsies may be performed under topical anesthesia in an outpatient clinic setting. The second technique is more complex, invasive, and is performed under regional and/or systemic anesthesia in an operating room. This method utilizes a vitreous cutter that requires a high-speed guillotine blade that can “chop” the vitreous gel and aspirate fluid. Advantages of the vitrectomy cutter technique include the ability to assure adequate sample volume, intraocular visualization of the vitreous removed with endoillumination, simultaneous control of intraocular pressure, diminished traction on the retina, and possibly the removal of insoluble molecular species. 12 13, 14

Clinical proteomic analysis is highly dependent on the quality of biological samples.15 The composition of the samples may vary by intraocular location or by sampling method.7 It is possible that a needle technique may remove soluble or non-bound proteins, whereas cutting techniques may provide additional insoluble or bound constituents. 16, 17 Proteins may be degraded or adsorbed during harvesting, transport and storage, which may vary by technique. The plastic tubing, for example, attached to the aspiration line of the vitrectomy cutter may adsorb positively charged molecules.18 Differing methods of sampling and archiving tissues may not be comparable and may limit the validity of study comparisons. 8, 15, 19 How each of the two techniques effect the extraction of proteins is not fully understood. Even though proteomic analyses of tissue biopsies are complex and expensive, they promise to discover the next “VEGF”-like therapeutic target for ophthalmic disease and will be part of pre-clinical and clinical trials. Vitreous biopsies are the key first step. To take advantage of this emerging technology, we need insight into whether surgical techniques affect the samples. The purpose of this study was to determine differences in proteins extracted by the needle and vitreous cutter biopsy techniques.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research (IRB) at the University of Iowa, was HIPPA compliant, adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and patients underwent informed consent.

Surgical technique

A single-step transconjunctival 23-gauge trocar cannula system (Alcon Laboratories Inc, Fort Worth, TX) was used to create sclerotomies. 20 One-half-ml of undiluted vitreous (infusion in the off position) was aspirated into 3-cc syringes attached to either a 23-gauge needle or vitreous cutter instrument (Alcon Laboratories Inc, Fort Worth, TX). In the operating room, vitreous samples were processed immediately by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 5 minutes at room temperature to remove particulate matter (centrifuge type) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were then stored at −80°. At the time of biopsy, two surgeons gave a subjective grade for vitreous viscidity as low, medium, or high based on the vitreous appearance, presence of insoluble material, clarity, aspiration quality, and intraoperative surgical observation.

Protein Analysis

The albumin and IgG proteins were removed from all vitreous samples using the Aurum Serum Protein Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). Total protein was measured in five 1.5-µL samples of the clarified protein solutions from each acquisition method using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). Protein quantity was determined via UV absorbance at 280 nm (Stoscheck, Methods in Enzymology, 1990, 182, 50–68).

SDS-PAGE

Twenty µL of the clarified, soluble protein solution was added to denaturing Nu-PAGE LDS sample buffer and NuPAGE reducing agent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were boiled for ten minutes in preparation for electrophoresis. Invitrogen NuPAGE Novex precast 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient mini SDS-PAGE gels were run at 150 V for 75 minutes using MOPS NuPAGE running buffer. Gels were then fixed in 50% MeOH, 10% glacial acetic acid for 30 minutes on a rocker at room temperature. The gel was rinsed for 5 minutes in 750 mL distilled water and then rinsed in fresh distilled water overnight on a rocker at room temperature. Following rinses, the gel was incubated with 1.3 mM sodium thiosulfate solution for 2 minutes followed by three 30-second washes with distilled water and then an incubation in 12 mM silver nitrate solution on a rocker at room temperature for 30 minutes. The gel was rinsed 3x5 min with distilled water and then developed in 26 µM sodium thiosulfate, 0.28 M sodium carbonate solution with 0.05% formaldehyde until desired band intensity was achieved. To stop the development reaction, the gel was washed in 38 mM EDTA solution.

LC-MS/MS

Albumin-depleted vitreous samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and quantified by silver staining. Samples containing 20 µg of protein were reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 minutes in buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 3M Urea) and alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide for 60 minutes in the dark. Samples were diluted with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.5) to a final concentration of 0.5M Urea. One microgram of sequence-grade trypsin (Promega) was added to each sample and incubated overnight at 37°C. Each sample was spiked with a tryptic-digest of bovine serum albumin (BSA) containing iodoacetic acid alkylated cysteine residues (Michrom Bioresources) at a 1:75 ratio (270 ng BSA: 20,000 ng sample) and trypsin-digested overnight. Samples were acidified and desalted on Vydac C18 spin-columns (The Nest Group) and subjected to strong-cation exchange (SCX) fractionation on polysulfoethyl A packed spin-columns (The Nest Group) according to the manufacturers protocol. Briefly, desalted samples were dissolved into SCX buffer B (5 mM KHPO4, 25 % acetonitrile (ACN)), loaded onto the SCX spin-columns, and the tryptic digest were released from the SCX spin-columns using a seven-step KCl elution gradient developed from a mixture of buffer B and buffer C (5 mM KHPO4, 25% ACN, 350 mM KCl). Salt-bumped eluted fractions were desalted, dried down, and dissolved into mass spectrometry loading buffer (1% acetic- acid, 1% ACN). The samples were subjected to LC-MS/MS on the Agilent Accurate-Mass Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer interfaced with the HPLC Chip Cube. The samples were loaded onto the large capacity C18 Chip II (160nl enrichment column, 9 mm analytical column). The samples were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis using a 90 minute gradient from 1.5% to 35% buffer B (100% ACN, 0.8% AA). The data-dependent settings included: a maximum precursor of 10 ions per cycle, a medium isolation width (~4 AMU), precursor masses were dynamically excluded for 30 seconds after 5 MS/MS in a 30 second time-window. Mass spectrometry capillary voltage and capillary temperature settings were set to 1800 V and 330 C, respectively. The infused reference mass of 1221.9906 was used to correct precursor m/z masses after the end of each LC-MS/MS experiment.

Bioinformatics

The raw .d files were converted by trapper to mzXML files and were searched against the SwissProt human database with a peptide mass tolerance of 50 ppm using the Sage-n Research Sorcerer2 SEQUEST Software version 4.0.4. The search modifications included a single trypsin miss-cleavage, a static carbamidomethylation on cysteine residues (C = 57.02146 AMU), and differential modifications for oxidized methionine (M = 15.9949 AMU), phosphorylated (STY = 79.9663 AMU) serine, tyrosine, and threonine, and ubiquitinated lysine (K = 114.0429 AMU) was used for post-translational modifications. The masses for the modifications phosphorylation, ubiquitination, carbamidomethylation and oxidation were 79.9663, 114.0429, 57.02146 and 15.9949 AMU, respectively. Scaffold 2.02.03 was used to visualize peptide and protein identifications. The software included the PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet software to assign statistical probabilities on the MS data. The data were filtered based upon the minimum protein ID probability of 80%, the minimum peptide ID probability of 50% and the minimum number of peptides of 2. The identified protein’s spectral counts were normalized to the ratio of the needle over cutter sample extraction experiments identified bovine serum albumin carboxymethylated cysteine (C = 58.0055 AMU) peptides for equal sample loading. Peptide spectra confidence levels were set between 80 – 90% and unique peptide hits were set to 1 or 2. The spectral counts were normalized for the samples by using the ratio of BSA in the needle sample compared to that in the cutter sample. The values were multiplied by the cutter sample raw values. The normalized values were plotted in Excel using the scatter plot function. A best-fit linear trend line was created to obtain a correlation coefficient for each dataset.

The normalized values were represented using a Bland-Altman plot. This plot depicted the relationship between the average of the two techniques (x-axis) and the difference between the two techniques (y-axis). The average difference line was plotted (y = 1) as well as the positive and negative standard deviation of the difference lines (y = −18.5, y = 20.5). Proteins that had significant spectral counts between the two techniques were plotted further away from the y = 1 line. Outliers were defined as the proteins outside of one standard deviation of the average line, or outside of the y = −18.5 and y = 20.5 lines.

Results

Patient Demographics

Sequential needle and vitreous cutter biopsy was performed in ten patients that included eight males and two females with an age range of 20 – 73 (Table 1). There were four right eyes and six left eyes. In each case, a 23-gauge needle was inserted through a preplaced 23-gauge cannula and an undiluted 0.5-cc vitreous sample was manually aspirated. This was immediately followed by insertion of the vitreous cutter instrument, activation of cutting for 20 seconds, and manual aspiration of an undiluted approximate 0.5-cc vitreous sample. Vitrectomy then proceeded as usual for indications that included proliferative diabetic retinopathy (2/10), retinal detachment (3/10), vitreous opacities (2/10), endophthalmitis (1/10), epiretinal membrane (1/10), and proliferative vitreoretinopathy with tractional retinal detachment (2/10) (Table 1). At the time of biopsy, two surgeons were asked to grade vitreous viscidity as low, medium, or high in each case(Table 1). In eight cases surgeons graded the vitreous as low or medium viscidity. In two cases with proliferative vitreoretinopathy (case 9 and 10), the vitreous was graded as high viscidity.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| Case | Age | Sex | Eye | Diagnosis | Viscidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | M | OD | Posterior vitreous detachment Vitreous Opacities |

Low |

| 2 | 15 | M | OD | Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment | Low |

| 3 | 45 | M | OS | Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment | Low |

| 4 | 62 | M | OS | Proliferative diabetic retinopathy | Medium |

| 5 | 49 | M | OS | Idiopathic uveitis with retinal vasculitis | Medium |

| 6 | 49 | F | OS | Infectious Endophthalmitis | Medium |

| 7 | 55 | M | OS | Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment | Medium |

| 8 | 73 | M | OD | Proliferative diabetic retinopathy | Medium |

| 9 | 69 | M | OD | Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy Tractional Retinal Detachment Diabetic retinopathy |

High |

| 10 | 20 | F | OS | Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy Tractional retinal detachment Retinopathy of Prematurity |

High |

Protein Quantification

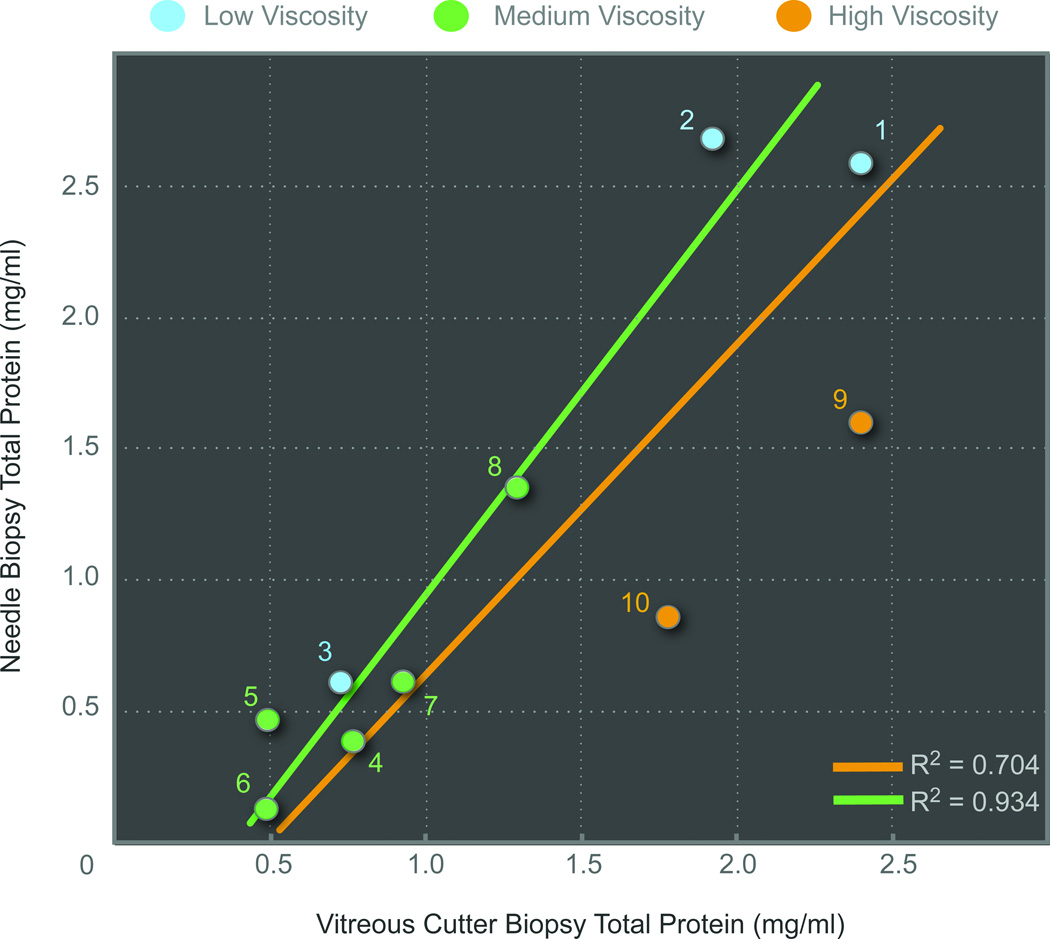

Affinity columns were used to deplete albumin and immunoglobulin from samples and isolate the remaining vitreous proteins, which is standard protocol for analysis since these proteins overwhelm analysis of less abundant proteins21. The total protein collected was quantified and measured 1.124 mg/ml (SEM = 0.287, range 0.135 – 2.679) for needle biopsies and 1.320 mg/ml (SEM = 0.238, range 0.492 – 2.402) for vitreous cutter biopsies. Following the depletion step, there was on average a 5-fold decrease in protein concentration, indicating that albumin and immunoglobulin constituted a high portion of protein content in the vitreous. There was a trend toward slightly more protein in the vitreous cutter biopsy, but this was not statistically significant (paired Student's t-test, p=0.61). The correlation between needle and vitreous cutter biopsy was R2 = 0.704 (Figure 1). In the two proliferative vitreoretinopathy samples with high viscidity, the protein concentration in the vitreous cutter was greater (1.7x) than the needle sample. If these two samples were excluded, the correlation between needle and vitreous cutter biopsies was R2 = 0.934 and the average total protein values were 1.104 mg/mL and 1.128 mg/mL, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total protein concentration obtained from needle and vitreous cutter biopsies.

Simultaneous needle and vitreous cutter instrument biopsies were performed in the same eye of ten patients (case number in circles). Surgeons graded vitreous viscidity as low (blue circle), medium (green circle), or high (yellow circle). The total protein concentration correlation between techniques was R2 = 0.704 (yellow line). If two patients with high viscidity vitreous were removed, the correlation was R2 = 0.934 (green line). There was a slight trend towards higher protein concentrations in the vitreous cutter samples.

Protein Analysis

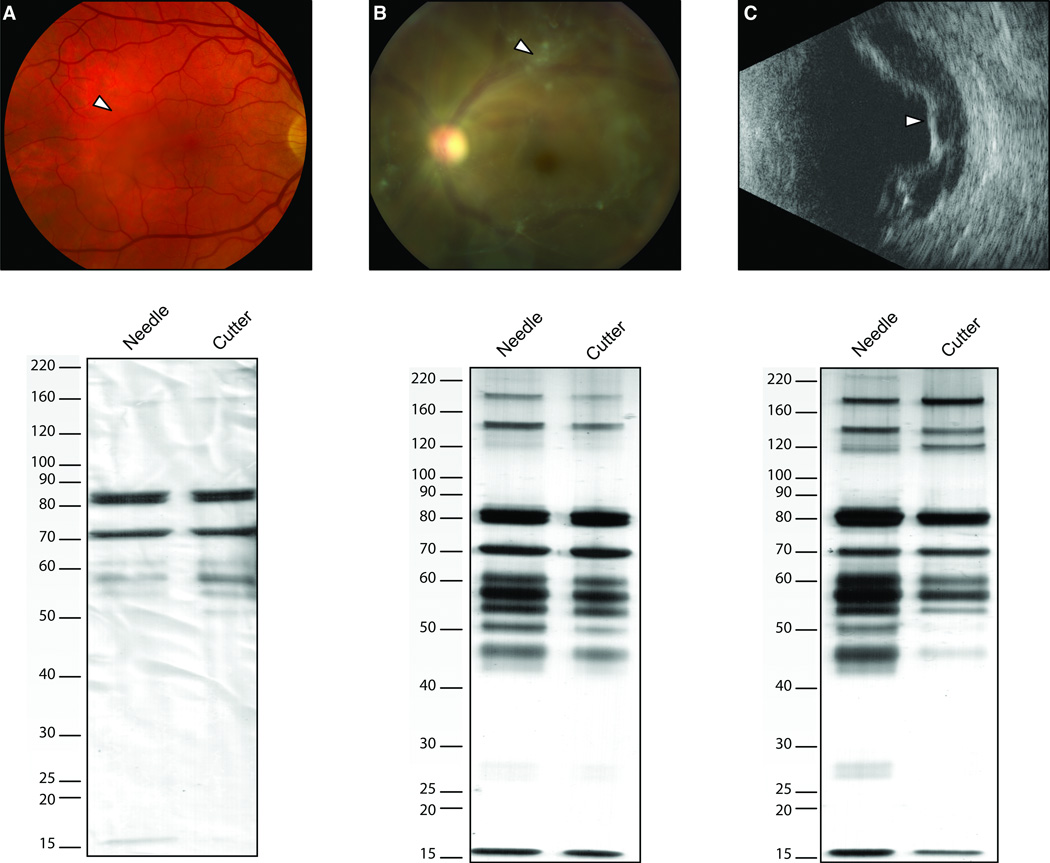

Protein samples from needle and vitreous cutter biopsies were visualized on 1-dimensional SDS-PAGE gels. Overall, the ten, paired samples showed similar profiles with respect to the number of protein bands and their respective sizes. In some eyes, however, band intensities for specific proteins varied between the needle and cutter samples. In low viscidity biopsies, for example, this variance was typically seen in protein bands in a range below 80 kDa. In some medium viscidity vitreous biopsies, the vitreous cutter sample had lower intensity of two bands (28 kDa and 180 kDa). In high viscidity vitreous samples, a range of protein bands (less than 50 kDa) in the cutter sample had less intensity, while one was absent (28 kDa). The protein band at 120 kDa also appeared different between the two samples, where the needle sample appeared to have a double band compared to the single band in the cutter profile (Figure 2C). Three case examples are discussed below, and the corresponding protein profiles are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Comparative vitreous protein profiles using one-dimensional SDS PAGE.

A. Case-1. Samples obtained by needle and vitreous cutter from a 61-year-old male with a visually significant vitreous opacity (arrowhead, fundus photo) showed different protein profiles in regards to number of protein bands as well as intensity of the bands, especially in the range below 80 kDa. B. Case-5. Samples obtained from a 49-year-old male with idiopathic uveitis, retinal vasculitis, and significant vitreous opacities (arrowhead, fundus photo) demonstrated similar number of protein bands. The protein band at 28 kDa is more intense in the needle sample than in the cutter sample. C. Case-10. Samples obtained from a 20-year-old female with a history of regressed retinopathy of prematurity and tractional retinal detachment (arrowhead, ultrasound) demonstrated similar band patterns. Some bands, especially of lower molecular weights (< 50 kDa) were more intense in the vitreous needle sample compared to the cutter sample. It appears that the cutter sample does not have a band at 28 kDa in this set of samples, a pattern that is similar to that found in case-5 (B).

Case-1

A 61-year-old-male developed visually significant floaters over two years. Although his visual acuity was 20/15 in the both eyes, the floaters significantly limited his ability to drive at night, hunt, read and watch television, especially in the right eye. A dilated fundus examination showed posterior vitreous detachments with a dense, large vitreous opacity overlying the macula in the right eye (Figure 2A). He underwent a needle biopsy followed by a 23-gauge vitrectomy in his right eye. The vitreous was graded as low viscidity (Table 1). The vitreous protein profiles from the different techniques showed a similar number of protein bands with some intensity variance between 50 and 60 kDa (Figure 2A). Corresponding to the low viscidity grade, the protein profile was not as complex as those obtained from eyes with inflammatory disease (case-5 and case-10), especially below 50 kDa or above 90 kDa.

Case-5

A 49-year-old male with bilateral idiopathic uveitis and retinal vasculitis developed vitreous opacities, worse in the left eye over two years. The floaters made driving and reading difficult. Subtenon’s Kenalog injections put the uveitis in remission, but did not improve his symptoms. The visual acuity was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/70 in the left eye, there were mild nuclear sclerotic cataracts, and a dilated fundus examination showed dense vitreous opacities overlying the maculas (Figure 2B), along with a mild epiretinal membrane in the left eye. There was mild inferior vascular sheathing. He underwent a needle biopsy followed by a 23-gauge vitrectomy in his left eye. The vitreous was graded as medium viscidity (Table 1). The protein profiles obtained from the needle and cutter were very similar in the number of proteins, however, some proteins appeared more intense (Figure 2B). For example, the protein band at approximately 28 kDa, was more intense in the vitreous cutter sample compared to the needle sample. This difference was not observed for the majority of the protein bands.

Case-10

A 20-year-old female was monocular due to regressed retinopathy of prematurity. Her right eye was phthisical with no light perception vision and her left eye was 20/400 due to a chronic epiretinal membrane. She noticed a recent visual decline in the left eye and presented with count fingers at 2-feet vision. On examination, there was a moderate nuclear and posterior subcapsular cataract, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, a macula-off tractional retinal detachment on ultrasound (Figure 2C), and a 3-clock hour superotemporal retinal break. She underwent a needle biopsy followed by a 23-gauge vitrectomy, extensive membrane peeling, and silicone oil placement. The vitreous was graded as high viscidity (Table 1). The vitreous protein profiles showed very similar patterns (Figure 2C). However, bands less than 50 kDa were more intense in the needle sample compared to the cutter sample. This pattern was similar to case #5.

Proteomic Analysis

To overcome the sensitivity and specificity limitations of SDS-PAGE, a more detailed comparative analysis of vitreous biopsy techniques was performed using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Vitreous proteins were trypsinized and the resulting peptides subjected to liquid chromatography. Peptides were sequenced using tandem mass spectrometry, assigned to their parent protein bioinformatically, and quantified for comparison using spectral counts. We identified as many as 11,189 spectra corresponding to 1,968 unique proteins. The high number of proteins detected may be due to increased detection sensitivity of the current mass spectrometry instrumentation or false positives and low stringency filter criteria set at an 80% confidence level and single peptide hit for protein identification. Following application of high stringency filtering criteria that included two or more peptide hits per protein and a greater than 90% confidence level, 8360 spectra corresponding to 87 unique proteins were selected for further analysis. Although these numbers are not directly comparable to previous proteomics studies using different instrument platforms, these results compared favorably to those obtained using similar filtering criteria.5, 22

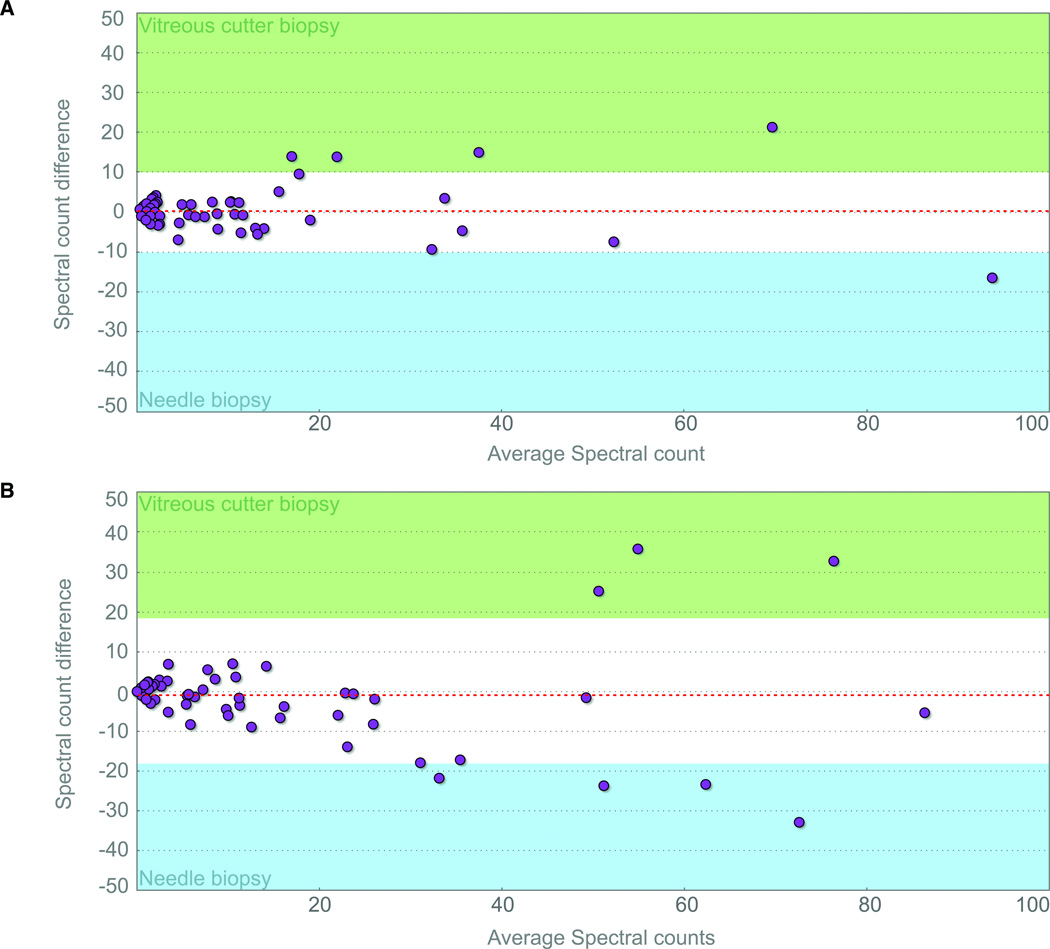

After graphing peptide spectral counts from the needle biopsy versus the cutter biopsy for each eye, a regression line and correlation coefficient was determined. Results from two samples are shown in figure 3. The correlation coefficient was very high with R2 = 0.949 and R2 = 0.976. Next, we determined the presence of outlier proteins by identifying peptides with expression differences greater than 1-standard deviation (Table 2). The vitreous cutter biopsy showed higher spectral counts for several peptides. Vitamin D binding protein and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, for example, had higher spectral counts in both cases. Myosin-11 displayed higher spectral counts in sample-1. Transthyretin and leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein spectral counts were higher in sample-2. For some proteins, higher spectral counts were observed in the needle biopsies. Ceruloplasmin, alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein, and Ig subunits displayed higher spectral counts in the first sample, whereas only hemoglobin subunit beta had higher spectral counts in second sample. These details are summarized in table 2. The graphs also suggested that proteins with higher expression showed more variance. Among these outliers, there was no trend or pattern in protein size, function, or cellular location. There were no specific proteins identified by one biopsy technique that were missing with the other technique.

Figure 3. Peptide spectral counts shows a high correlation between vitreous cutter and needle biopsy profiles on a Bland-Altman plot of LC-MS/MS data.

A. Sample-1. Idiopathic uveitis. B. Sample-2. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The Bland-Altman plot shows the average spectral count values between the vitreous cutter and needle biopsies ((vitreous cutter + needle)/2); x-axis) graphed against the difference in spectral counts between the two techniques (vitreous cutter – needle; y-axis). Red, dotted line: average difference; gray region: 95% limits of agreement (±1.96 SD); green region: outlier with greater detection in the vitreous cutter instrument biopsy; blue region: outlier with greater detection in the needle biopsy.

Table 2.

Differentially extracted proteins obtained in vitreous cutter and needle. Protein outliers were identified by LC-MS/MS and appear outside the confidence interval in figure 3. Sample-1 was a patient with uveitis and sample-2 was a patient with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Both vitreous samples were medium viscidity.

| Sample # |

Higher protein quantity in Cutter biopsy |

Higher protein quantity in Needle biopsy |

Protein name | Gene Symbol |

UniProt KB |

MW (kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 & 2 | ● | Vitamin D binding protein | GC | P02774 | 53.0 | |

| 1 & 2 | ● | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 | ORM1 | P02763 | 23.5 | |

| 1 | ● | Ig kappa chain C region | IGKC | P01834 | 11.6 | |

| 1 | ● | Ig alpha-1 chain C region | IGHA1 | P01876 | 37.7 | |

| 1 | ● | Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein | AHSG | P02765 | 39.3 | |

| 1 | ● | Ceruloplasmin | CP | P00450 | 122.2 | |

| 1 | ● | Myosin-11 | MYH11 | P35749 | 227.3 | |

| 2 | ● | Hemoglobin subunit beta | HBB | P68871 | 16.0 | |

| 2 | ● | Transthyretin | TTR | P02766 | 15.9 | |

| 2 | ● | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein | LRG1 | P02750 | 38.2 |

Higher protein levels are indicated by “●” in either the needle or cutter column.

Discussion

Diagnostic vitreous samples are typically analyzed for the presence of pathogenic cells, bacteria, viral particles, immunoglobulin, cytokines, and additional proteins involved in ocular disease. 23,24 Depending on the surgical indication or specific vitreoretinal pathology, the vitreous may contain insoluble or formed collagenous material that can block a needle and limit sample volume. Despite the ability of vitrectomy instruments to obtain larger tissue samples, costs, speed of acquisition and lower complication rates make needle biopsies in the outpatient setting a more desirable sampling option. With either technique, diagnostic tests may be negative or equivocal requiring repeat biopsies. 25, 26

This study compared vitreous proteins obtained by the two most commonly used vitreous biopsy techniques on three protein analytical platforms. Overall, our findings suggest that for the purpose of proteomic analysis, needle biopsy techniques are not inferior to vitreous cutter, but rather two methods may not be quantitatively comparable for all proteins. The concern that insoluble or viscous material might have occluded a needle and this method may be enriched in proteins free in solution rather than proteins bound to insoluble material does not seem to be true. Although differing viscidity is clinically evident during surgery as schlieren or retarded movement of scattered visible particulate matter such as cells, fibrinogen, or fibrotic material,6,7 needle biopsies did not prove inferior to the vitreous cutter at extracting protein. At the molecular level, the change in viscidity may be due to broad compositional changes in the gel, posttranslational modifications, altered protein-protein and protein-glycoprotein interactions, or new cellular and extracellular constituents.7 Because of the small sample size and limited number of diagnoses, it will be necessary to validate these findings in future studies that focus on specific diagnoses and specific proteins.

In support that insoluble vitreous components may be equally represented, we found that the concentration of total protein was very similar whether biopsies were obtained with a needle or vitreous cutter instrument. The exception to this was high viscidity vitreous in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. In these cases, the vitreous cutter instrument was superior and extracted more total protein. Nevertheless, overall protein profiles appeared similar on protein gels with only some differences in band intensities and no clear trend towards either technique. Small variations in band intensity on silver stained gels is not uncommon, and understanding the significance of these will require further study of multiple, replicative samples focused on single diseases. It is also interesting to note the significant reduction in total protein following removal of albumin and IgG from the vitreous. Although other proteins may non-specifically bind albumin and become removed during the processing, it supports the observation that a large fraction of vitreous protein is made up of albumin, IgG, and a few other serum proteins.4, 27, 28 Finally, after analyzing peptides on a highly sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS platform, we determined again that both techniques were very similar. Some quantitative differences in specific proteins were present, but no technique was favored over the other. It is not clear why these peptide differences were present, but it may depend on the varying density and composition of vitreous substructures or protein-protein interactions present in specific diseases.3, 5, 7 Further studies will be required to determine the underlying reason for these differences.

Proteomic analysis is especially important in the examination of complex extracellular matrices such as the vitreous where several tissues both inside the eye and remote to the eye contribute to the diseased state. In these cases, genomic analysis of local tissue gene expression may provide a very limited view of disease pathophysiology. For example, complement factor proteins are key agents in age-related macular degeneration, but they are mostly synthesized in the liver, circulate to the eye, and can be detected in the vitreous.22, 29, 30 Since the protein samples obtained from needle biopsies are comparable to those obtained from vitreous cutter biopsies, our results suggest that typically non-surgical diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration or diabetic macular edema, are accessible to vitreous proteomic analysis through needle biopsies. With the identification of protein biomarkers, one of the key issues will be whether they correlate with disease diagnosis, progression, or response.31 Although this analysis suggests that the two sampling techniques yield very similar results in terms of total protein profiles, specific biomarker levels associated with particular diseases may be best measured by one or the other method. In some situations the vitreous cutter may be optimal, but in others the vitreous needle aspiration may be best. This may also depend on whether the patient has a condition that is treated in the operating room or minor procedure room.

A broad range of diagnoses were selected for this initial proteomics comparison, but future studies should look in greater depth at specific diagnoses. An additional limitation is how the needle biopsies were taken. For patient safety reasons, we elected to perform the needle biopsy through the cannula for clear visualization during insertion, aspiration, and retraction and with infusion readily available in case of hypotony. Although this avoided potential protein contamination that might be present if the needle was first passed through conjunctiva, sclera, as is typically done in the clinic setting, we do not feel this would have a significant effect on protein detection. For now it seems that specific instrumentation should not be a limiting factor for further proteomics analyses of the vitreous. Access to these tools offers the opportunity to identify diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in complex ophthalmic disease in both the clinic and operating room. 5, 32, 33

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: An unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY.

Footnotes

The authors have no commercial or financial interests associated with this article.

References

- 1.Skeie JM, Mahajan VB. Dissection of human vitreous body elements for proteomic analysis. J Vis Exp. 2011;(47) doi: 10.3791/2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Goff MM, Bishop PN. Adult vitreous structure and postnatal changes. Eye (Lond) 2008;22(10):1214–1222. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Los LI, van der Worp RJ, van Luyn MJ, Hooymans JM. Age-related liquefaction of the human vitreous body: LM and TEM evaluation of the role of proteoglycans and collagen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(7):2828–2833. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walia S, Clermont AC, Gao BB, et al. Vitreous proteomics and diabetic retinopathy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(5–6):289–294. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.518912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J, Liu F, Cui SJ, et al. Vitreous proteomic analysis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Proteomics. 2008;8(17):3667–3678. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friberg TR, Tano Y, Machemer R. Streaks (schlieren) as a sign of rhegmatogenous detachment in vitreous surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88(5):943–944. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose GE, Billington BM, Chignell AH. Immunoglobulins in paired specimens of vitreous and subretinal fluids from patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74(3):160–162. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallick P, Kuster B. Proteomics: a pragmatic perspective. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):695–709. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davuluri G, Espina V, Petricoin EF, 3rd, et al. Activated VEGF receptor shed into the vitreous in eyes with wet AMD: a new class of biomarkers in the vitreous with potential for predicting the treatment timing and monitoring response. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(5):613–621. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis JL, Miller DM, Ruiz P. Diagnostic testing of vitrectomy specimens. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(5):822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfahler SM, Brandford AN, Glaser BM. A prospective study of in-office diagnostic vitreous sampling in patients with vitreoretinal pathology. Retina. 2009;29(7):1032–1035. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181a2c1eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolis R. Diagnostic vitrectomy for the diagnosis and management of posterior uveitis of unknown etiology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19(3):218–224. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282fc261d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quiroz-Mercado H, Guerrero-Naranjo J, Agurto-Rivera R, et al. Perfluorocarbon-perfused vitrectomy: a new method for vitrectomy--a safety and feasibility study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243(6):551–562. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-1063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quiroz-Mercado H, Rivera-Sempertegui J, Macky TA, et al. Performing vitreous biopsy by perfluorocarbon-perfused vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troyer D. Biorepository standards and protocols for collecting, processing, and storing human tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;441:193–220. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-047-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroh EM. Microbiologic yields and complication rates of vitreous needle aspiration versus mechanized vitreous biopsy in the endophthalmitis vitrectomy study. Retina. 1999;19(6):576–578. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199919060-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han DP, Wisniewski SR, Kelsey SF, et al. Microbiologic yields and complication rates of vitreous needle aspiration versus mechanized vitreous biopsy in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Retina. 1999;19(2):98–102. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Lee ML. Biocompatible polymeric monoliths for protein and peptide separations. J Sep Sci. 2009;32(20):3369–3378. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel N, Solanki E, Picciani R, et al. Strategies to recover proteins from ocular tissues for proteomics. Proteomics. 2008;8(5):1055–1070. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahajan VB, Tarantola RM, Graff JM, et al. Sutureless triplanar sclerotomy for 23-gauge vitrectomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(5):585–590. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krief G, Deutsch O, Gariba S, et al. Improved visualization of low abundance oral fluid proteins after triple depletion of alpha amylase, albumin and IgG. Oral Dis. 2011;17(1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao BB, Chen X, Timothy N, et al. Characterization of the vitreous proteome in diabetes without diabetic retinopathy and diabetes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(6):2516–2525. doi: 10.1021/pr800112g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Augsburger JJ. Invasive diagnostic techniques for uveitis and simulating conditions. Trans Pa Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1990;42:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzales JA, Chan CC. Biopsy techniques and yields in diagnosing primary intraocular lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27(4):241–250. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9065-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Char DH, Ljung BM, Miller T, Phillips T. Primary intraocular lymphoma (ocular reticulum cell sarcoma) diagnosis and management. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(5):625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conlon MR, Craig I, Harris JF, et al. Effect of vitrectomy and cytopreparatory techniques on cell survival and preservation. Can J Ophthalmol. 1992;27(4):168–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamane K, Minamoto A, Yamashita H, et al. Proteome analysis of human vitreous proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2(11):1177–1187. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300038-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakanishi T, Koyama R, Ikeda T, Shimizu A. Catalogue of soluble proteins in the human vitreous humor: comparison between diabetic retinopathy and macular hole. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;776(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skeie JM, Fingert JH, Russell SR, et al. Complement component C5a activates ICAM-1 expression on human choroidal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(10):5336–5342. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zipfel PF, Jokiranta TS, Hellwage J, et al. The factor H protein family. Immunopharmacology. 1999;42(1–3):53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN. Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(11):845–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukai N, Nakanishi T, Shimizu A, et al. Identification of phosphotyrosyl proteins in vitreous humours of patients with vitreoretinal diseases by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis/Western blotting/matrix-assisted laser desorption time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45(Pt 3):307–312. doi: 10.1258/acb.2007.007151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shitama T, Hayashi H, Noge S, et al. Proteome Profiling of Vitreoretinal Diseases by Cluster Analysis. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2(9):1265–1280. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]