Abstract

Rearrangement hotspot (Rhs) and related YD-peptide repeat proteins are widely distributed in bacteria and eukaryotes, but their functions are poorly understood. Here, we show that Gram-negative Rhs proteins and the distantly related wall-associated protein A (WapA) from Gram-positive bacteria mediate intercellular competition. Rhs and WapA carry polymorphic C-terminal toxin domains (Rhs-CT/WapA-CT), which are deployed to inhibit the growth of neighboring cells. These systems also encode sequence-diverse immunity proteins (RhsI/WapI) that specifically neutralize cognate toxins to protect rhs+/wapA+ cells from autoinhibition. RhsA and RhsB from Dickeya dadantii 3937 carry nuclease domains that degrade target cell DNA. D. dadantii 3937 rhs genes do not encode secretion signal sequences but are linked to hemolysin-coregulated protein and valine-glycine repeat protein G genes from type VI secretion systems. Valine-glycine repeat protein G is required for inhibitor cell function, suggesting that Rhs may be exported from D. dadantii 3937 through a type VI secretion mechanism. In contrast, WapA proteins from Bacillus subtilis strains appear to be exported through the general secretory pathway and deliver a variety of tRNase toxins into neighboring target cells. These findings demonstrate that YD-repeat proteins from phylogenetically diverse bacteria share a common function in contact-dependent growth inhibition.

Keywords: bacterial competition, CDI, cell-cell interaction, DNase activity, toxin/immunity genes

Rearrangement hotspot (rhs) elements were first identified as sites that promote recombination in Escherichia coli (1). The region between rhsA and rhsB is frequently duplicated in E. coli cells, presumably because these genes share large regions (∼3.7 kbp) of sequence identity and are positioned relatively close to one another in the genome. The large invariant rhs sequence was originally termed the “core” (2) and encodes the conserved N-terminal 1,240 residues of E. coli Rhs proteins including the YD-peptide repeats that define this protein family (Pfam ID: PF03527 and PF05593). More recent analysis has revealed that enterobacterial Rhs proteins are composed of four distinct regions and that the core can vary among family members (3). Rhs C-terminal regions (Rhs-CT) are highly variable and encoded by “core extensions” with GC content and codon bias that are different from sequences encoding the N-terminal regions (2–4). The Rhs-CT region is sharply demarcated by a PxxxxDPxGL peptide motif within the adjacent hyperconserved domain (3). This structure suggests that rhs genes are composites formed by the insertion of horizontally transferred core-extension sequences (2, 3). Rhs-CT polymorphism is extensive, and different strains of a given species typically contain a distinct complement of rhs alleles (2, 3, 5). Rhs are distributed throughout β-, γ-, and δ-proteobacteria, and genes encoding more distantly related YD-peptide repeat proteins are found in Gram-positive bacteria, some fungi, and higher metazoans through the vertebrates (6–8). This broad distribution suggests that Rhs/YD-repeat proteins play a fundamental role in biology. Indeed, the rhs genes of E. coli and Shigella strains show evidence of strong positive selection (9); however, the functions of this gene family are not well understood.

We recently found that some Rhs-CT regions share sequence identity with the toxic effector domains of contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) systems (10). CDI systems mediate interbacterial competition and encode large CdiA proteins with highly variable C-terminal toxin domains (CdiA-CT) (11, 12). CdiA is exported to the inhibitor cell surface where it engages receptors on related bacteria and delivers its toxin into target cells (13, 14). CDI+ bacteria also carry cdiI immunity genes immediately downstream of cdiA, and together these genes form a family of polymorphic toxin/immunity pairs. CdiI immunity proteins bind and neutralize CdiA-CT toxins to protect CDI+ cells from autoinhibition (11). Because CdiI proteins are highly variable, they protect cells from cognate CdiA-CT but not from the toxins deployed by other CDI systems. Similar to CDI, the rhsB locus of Dickeya dadantii 3937 encodes a toxin/immunity protein pair. RhsB-CT inhibits growth when expressed in E. coli, but this toxicity is blocked by coexpression of an immunity protein (RhsIB) encoded immediately downstream of rhsB (10). These parallels with CDI led us to examine the role of Rhs proteins in intercellular competition. We find that D. dadantii 3937 uses two of its three Rhs proteins to inhibit the growth of neighboring cells in a contact-dependent manner. Additionally, we show that distantly related wall-associated protein A (WapA) from Bacillus subtilis strains also carries variable C-terminal toxin domains and is encoded with a linked immunity gene. Like D. dadantii 3937, B. subtilis 168 deploys WapA to inhibit adjacent nonimmune cells. Together, these results demonstrate that YD-repeat proteins from diverse bacteria share a common function in intercellular competition.

Results

Rhs Proteins Mediate Intercellular Competition in D. dadantii 3937.

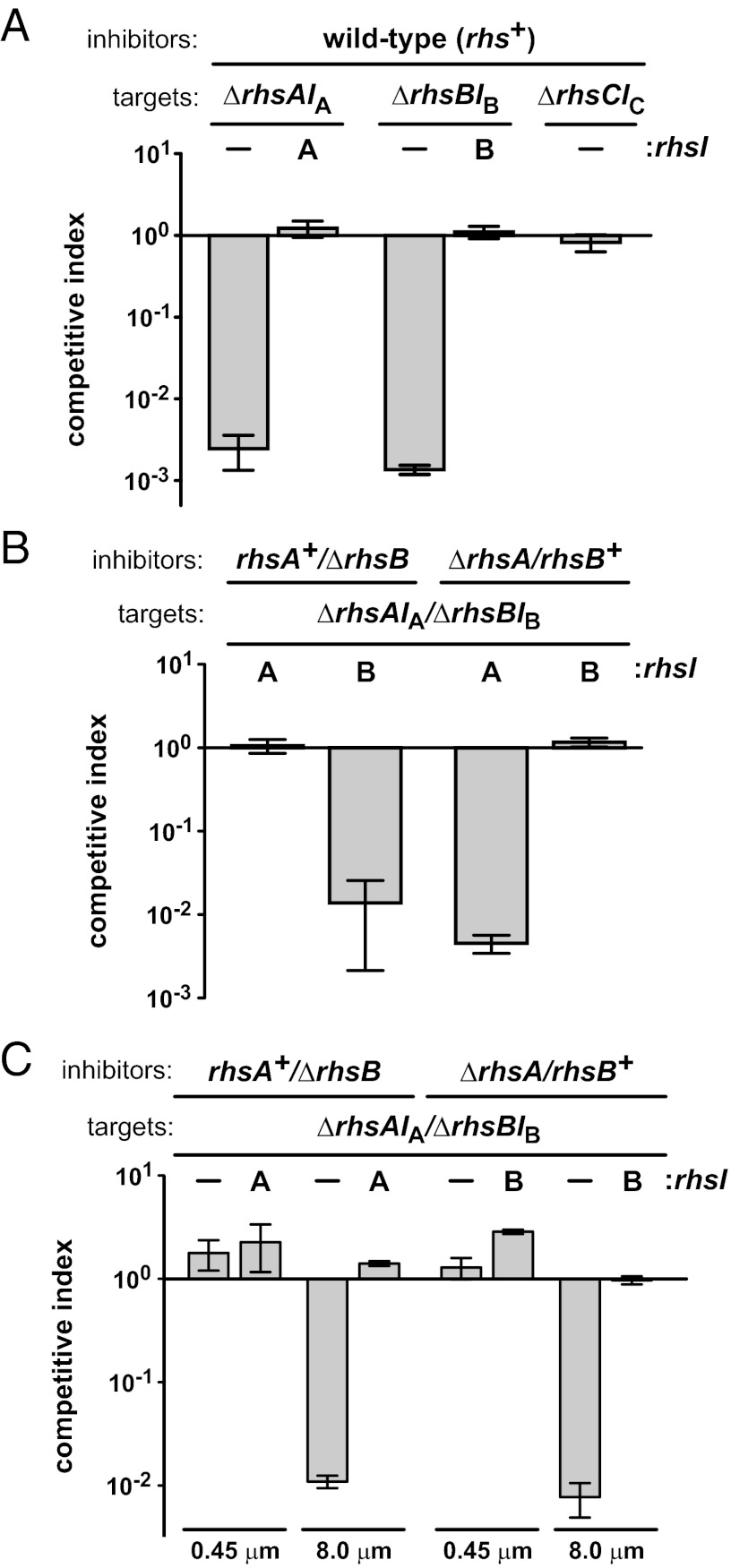

To explore the role of Rhs in intercellular competition, we examined the three rhs loci in Dickeya dadantii 3937 (Fig. S1). We first generated target strains deleted for individual rhs/rhsI gene pairs, reasoning that cells lacking rhsI immunity genes should be susceptible to inhibition by the wild-type rhs+ strain. Indeed, ∆rhsA-∆rhsIA and ∆rhsB-∆rhsIB mutants were outcompeted by wild-type D. dadantii 3937 during coculture on solid medium, whereas growth of the ∆rhsC-∆rhsIC mutant was unaffected (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that D. dadantii 3937 uses RhsA and RhsB for intercellular competition. The Rhs toxin/immunity model predicts that RhsI proteins should protect cells from growth inhibition. Therefore, we reintroduced the rhsIA and rhsIB genes into ∆rhsA-∆rhsIA and ∆rhsB-∆rhsIB target cells, respectively, using a Tn7-based integration vector and tested the complemented strains in competitions with rhs+ cells. As predicted, each rhsI gene protected target cells from growth inhibition (Fig. 1A). Together, these results indicate that D. dadantii cells deploy Rhs to inhibit other cells and protect themselves with immunity proteins.

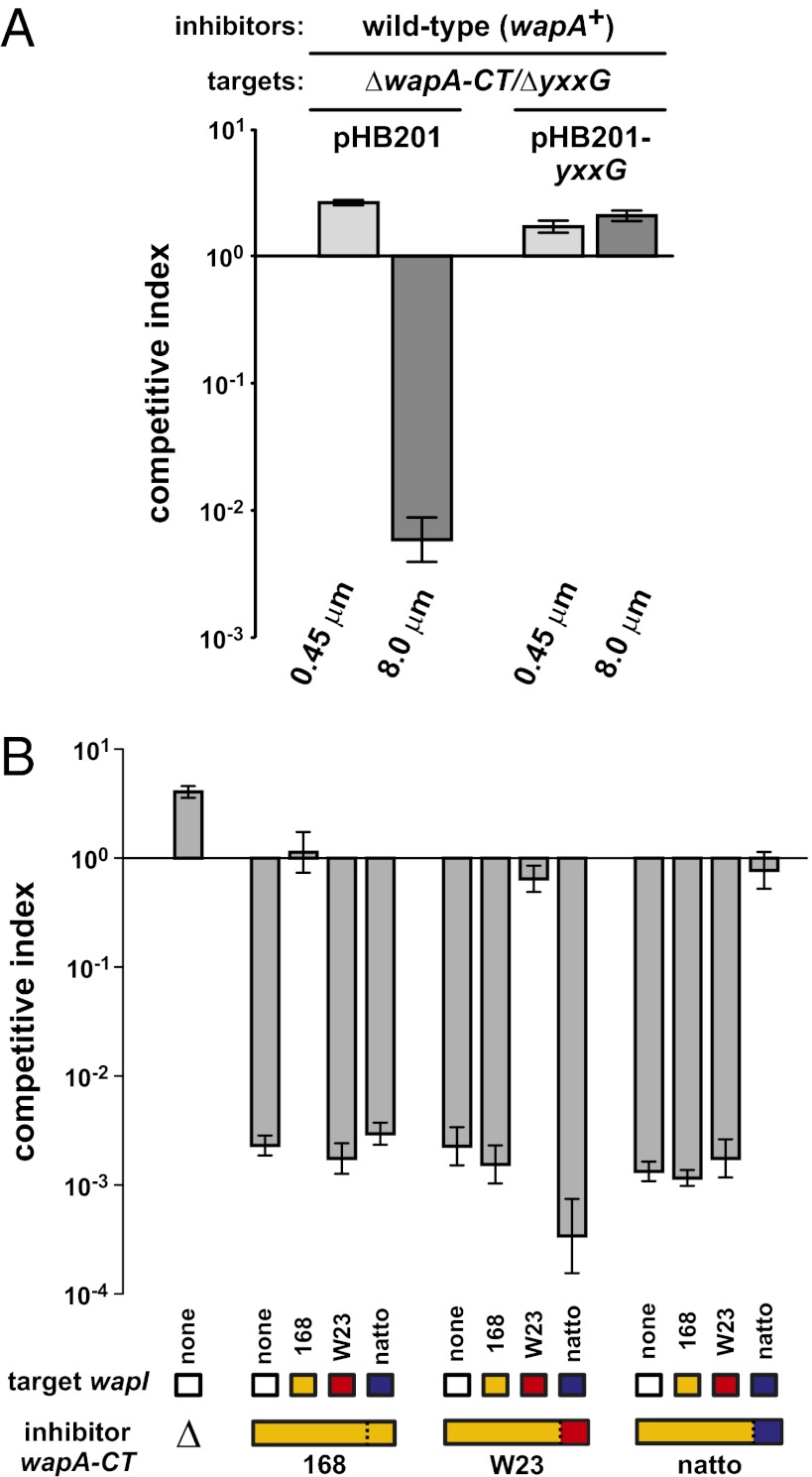

Fig. 1.

Rhs mediates contact-dependent inhibition. (A) Rhs mediates competition between D. dadantii 3937 cells. Wild-type inhibitors (rhs+) were cocultured with target cells lacking the indicated rhs loci. (B) Specificity of Rhs immunity. Inhibitors expressing either RhsA (rhsA+/∆rhsB) or RhsB (∆rhsA/rhsB+) were cocultured with targets lacking both rhsAIA and rhsBIB loci. (C) Rhs-mediated growth inhibition requires cell–cell contact. Inhibitor and target cells were separated by membranes containing 0.45-µm or 8.0-µm pores. In each panel, target cells were complemented with rhsIA or rhsIB where indicated. For all competitions, cells were cocultured at a 10:1 inhibitor-to-target ratio, and target cell growth is expressed as the competitive index as described in Materials and Methods.

RhsA and RhsB are nearly identical over 1,303 N-terminal residues, but their C-terminal toxin domains are divergent (Fig. S2A). Similarly, the associated RhsIA and RhsIB proteins are unrelated (Fig. S2B), suggesting that immunity is specific for each Rhs-CT. To test this hypothesis, we cocultured inhibitors that express only RhsA (rhsA+/∆rhsB) or RhsB (∆rhsA/rhsB+) with ∆rhsA-∆rhsIA/∆rhsB-∆rhsIB target cells complemented with either rhsIA or rhsIB. The rhsIA gene conferred immunity to rhsA+/∆rhsB inhibitors but not to ∆rhsA/rhsB+ cells (Fig. 1B). Similarly, rhsIB protected only targets from ∆rhsA/rhsB+ inhibitors (Fig. 1B), demonstrating the specificity of Rhs immunity. Because Rhs shares many features with CDI, we asked whether Rhs-mediated inhibition also requires close contact between cells. We repeated the competitions but separated inhibitors from target cells using membranes of different porosities. RhsA- and RhsB-mediated inhibition was not observed when cells were segregated with a membrane containing 0.45-µm pores, which allow transfer of soluble factors but prevent cell mixing (Fig. 1C). However, target cells were inhibited when separated from inhibitors by 8.0-µm pores (Fig. 1C), which allow bacterial cell passage. These results suggest that soluble Rhs is not inhibitory and that cells must be in close proximity for inhibition.

D. dadantii 3937 Rhs Toxins Degrade Target Cell DNA.

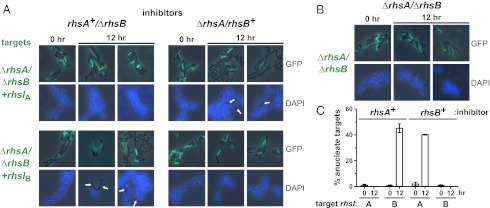

RhsA and RhsB inhibit cell growth, but their biochemical activities are uncharacterized. The RhsA-CT domain is a member of the endonuclease NS_2 family (PF13930), and RhsB-CT contains an HNH endonuclease motif (PF01844), suggesting that both toxins are nucleases. To test these predictions, we expressed each toxin inside E. coli and stained the cells with DAPI to visualize DNA by microscopy. Growth was inhibited after ∼1.5 h of RhsA-CT induction, and cells became elongated with condensed, centrally located nucleoids (Fig. S3A). The rhsB-CT coding sequence could not be isolated from the linked immunity gene, presumably because of toxicity. Therefore, we used controlled proteolysis of RhsIB to activate the RhsB-CT toxin inside E. coli cells (10, 15). RhsB-CT activation immediately arrested growth, and the inhibited cells became filamentous and lost DNA staining (Fig. S3B). Additionally, plasmid DNA was degraded rapidly in cells overproducing either RhsA-CT or RhsB-CT (Fig. S4), indicating that changes in DAPI staining probably reflect DNA damage. We also tested RhsC-CT and found that it inhibits E. coli growth but does not alter nucleoid structure (Fig. S3C). For each toxin, growth inhibition and the associated changes in cell morphology were blocked specifically by the cognate RhsI immunity protein (Fig. S3). We next asked whether DNA is degraded in D. dadantii 3937 target cells during coculture with rhs+ inhibitors. We labeled ∆rhsA-∆rhsIA/∆rhsB-∆rhsIB target cells with GFP to differentiate them from unlabeled inhibitors by fluorescence microscopy. DAPI staining revealed that many target cells had lost DNA during coculture with either rhsA+/∆rhsB or ∆rhsA/rhsB+ inhibitors (Fig. 2A). However, targets complemented with cognate rhsI retained their DNA (Fig. 2A), as did target cells that were cocultured with mock inhibitors that lack rhsAIA and rhsBIB loci (Fig. 2B). Quantification of these data showed that 40–45% of the targets lost DNA after 12 h of coculture with inhibitors (Fig. 2C). In contrast, none of the targets expressing cognate rhsI lost DNA staining (Fig. 2C). Together, these findings demonstrate that RhsA and RhsB toxins act by degrading target cell DNA.

Fig. 2.

RhsA and RhsB degrade target cell DNA. (A) Fluorescence microscopy of D. dadantii 3937 cocultures. Inhibitors expressing RhsA (rhsA+/∆rhsB) or RhsB (∆rhsA/rhsB+) were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio with GFP-labeled target cells lacking both rhsAIA and rhsBIB loci. Targets were complemented with either rhsIA or rhsIB where indicated. Samples from 0 and 12 h were stained with DAPI to visualize genomic DNA. Anucleate target cells are indicated by white arrows. (B) Mock competition between ∆rhsA/∆rhsB inhibitors and GFP-labeled ∆rhsA/∆rhsB target cells. (C) Quantification of anucleate target cells. GFP-labeled targets were examined visually and scored as anucleate if they completely lack DAPI staining. Reported values represent the mean ± SEM.

Valine-Glycine Repeat Proteins Are Required for RhsB-Mediated Inhibition.

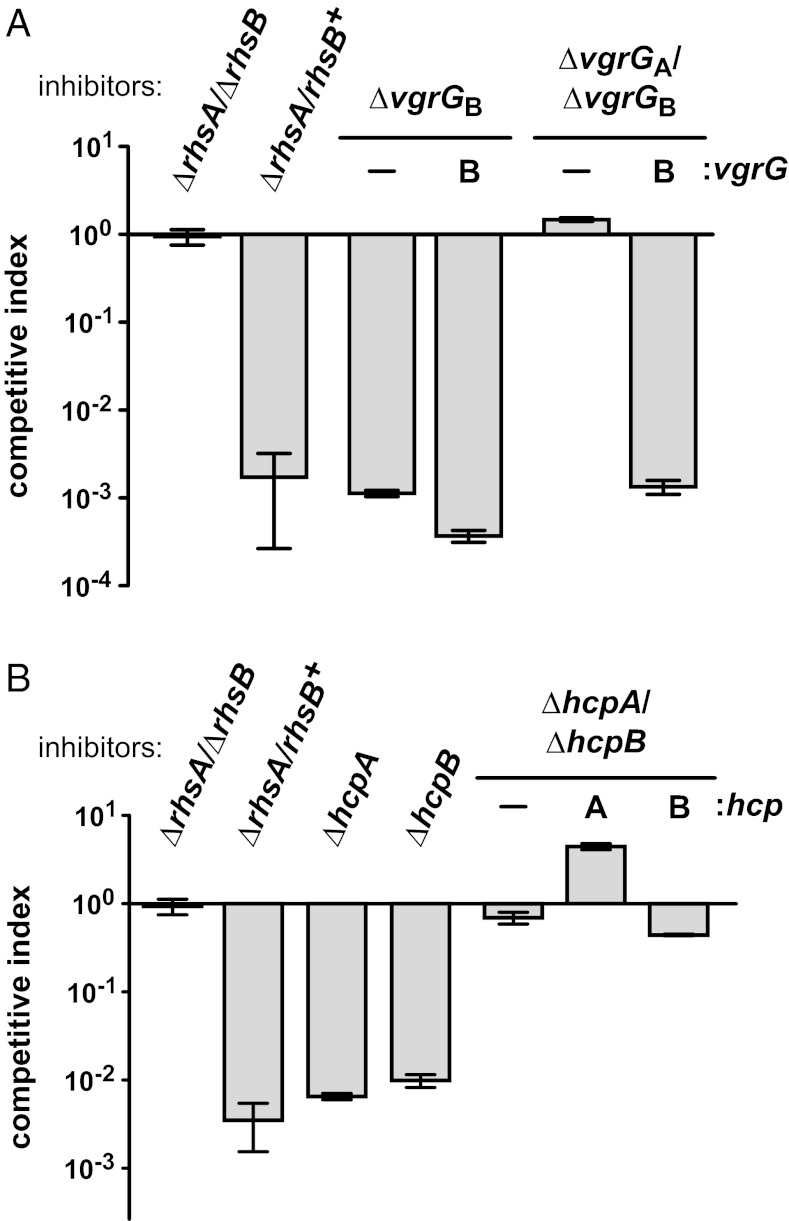

RhsA and RhsB deliver DNase domains into target cells, but both proteins lack recognizable secretion signal sequences, raising the question of how these toxins are exported. The rhs genes in many bacteria are linked to type VI secretion systems (T6SS), suggesting a possible mechanism of Rhs delivery. T6SS encode cell-puncturing structures that deliver effector proteins into both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells (16). This apparatus resembles a tailed bacteriophage assembly and is composed of a filamentous tube of hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp) protomers capped by valine-glycine repeat proteins (VgrG) (16). The D. dadantii 3937 rhsA and rhsB loci are linked to hcp and vgrG genes, whereas rhsC is adjacent to a full complement of T6SS genes (Fig. S1). To test whether T6S plays a role in RhsB-mediated inhibition, we deleted vgrG genes from ∆rhsA/rhsB+ inhibitor cells and examined the effects in growth competitions. Inhibitor cells lacking vgrGB still outcompeted targets, but deletion of both vgrGA and vgrGB genes abrogated this competitive advantage (Fig. 3A). Inhibitor activity was restored when vgrGB was reintroduced into the ∆vgrGA ∆vgrGB strain (Fig. 3A). We also tested the role of the linked hcp genes and again found that inhibitors lacking both hcpA and hcpB lost their competitive advantage over target cells (Fig. 3B). However, the ∆hcpA ∆hcpB phenotype could not be complemented with reintroduced hcpA or hcpB (Fig. 3B). The ∆hcpA ∆hcpB inhibitor strain grows more slowly than ∆rhsA-∆rhsIA/∆rhsB-∆rhsIB target cells. Therefore, the apparent loss of inhibitor cell function could reflect a difference in growth rates. Nevertheless, a copy of either vgrGA or vgrGB is required for the inhibitor cell phenotype, suggesting that Rhs proteins are exported using a T6S mechanism.

Fig. 3.

Role of T6SS genes in RhsB activity. (A) VgrG is required for RhsB-mediated inhibition. RhsB+ (∆rhsA/rhsB+) inhibitors carrying vgrG deletions were tested in competition with ∆rhsAIA ∆rhsBIB target cells. Inhibitors were complemented with vgrGB where indicated. (B) RhsB+ (∆rhsA/rhsB+) inhibitors carrying hcp deletions were tested in competition with ∆rhsAIA ∆rhsBIB target cells. Inhibitors were complemented with hcpB where indicated. Mock competitions using ∆rhsA/∆rhsB inhibitors are included in both panels. Inhibitors and targets were cocultured at a 10:1 ratio in all experiments. Target cell growth is expressed as the competitive index as described in Materials and Methods.

WapA Proteins from Bacillus subtilis Strains Contain C-terminal Toxin Domains.

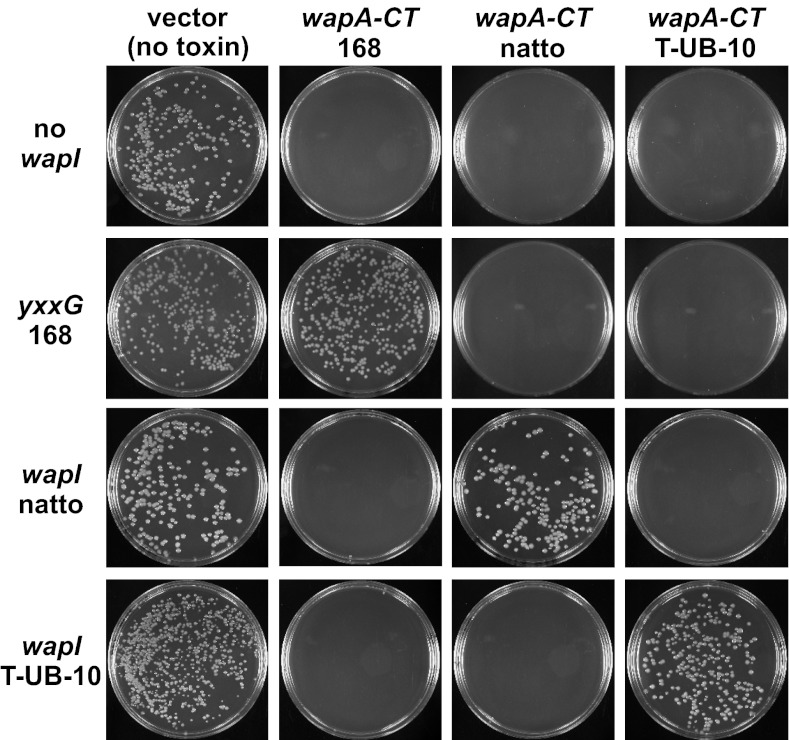

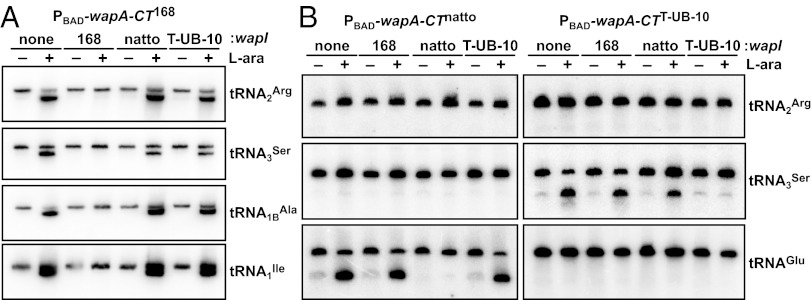

Rhs proteins are found only in Gram-negative bacteria, but many Gram-positive bacteria express large WapA proteins that contain YD-peptide repeats (8). As with Rhs and CdiA, the WapA-CT region is variable among different species and strains. All Bacillus subtilis strains contain a single wapA locus that encodes one of four distinct WapA-CT sequences (Fig. S5A). Moreover, the genes immediately following wapA also are variable, with four sequences that cosegregate with the wapA-CT alleles (Fig. S5B). These observations suggest that wapA and the downstream ORF encode cognate toxin/immunity pairs. To determine if WapA-CT domains are toxic, we cloned wapA-CT sequences from various B. subtilis strains under the arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter (PBAD) and tested whether the resulting plasmids inhibit E. coli cell growth. Although each wapA-CT plasmid could be maintained stably when expression was repressed with D-glucose, none of the plasmids could be introduced into E. coli cells in the presence of L-arabinose (Fig. 4). However, cells expressing predicted wapI immunity genes from a given B. subtilis strain were readily transformed with wapA-CT constructs from the same strain (Fig. 4). These findings suggest that WapA-CTs have toxic activities that are neutralized by cognate WapI immunity proteins. We next sought to identify the biochemical activities of WapA-CTs by examining nucleic acids from inhibited E. coli cells. Gel analysis revealed extensive tRNA cleavage in cells expressing wapA-CT168 from B. subtilis 168 but not in cells coexpressing the toxin and cognate wapI (yxxG) immunity gene. Northern blot analysis confirmed that several different tRNA isoacceptors are cleaved by this activity (Fig. 5A), and the cleavage sites were mapped to the 3′ end of E. coli tRNA2Arg using S1 nuclease protection analysis (Fig. S6). This RNase activity could account for the observed growth inhibition because tRNAs lacking the universally conserved 3′-CCA sequence cannot support protein synthesis. Additional Northern blot screening revealed that the other WapA-CT toxins are specific tRNases. Induction of wapA-CTnatto from B. subtilis subsp. ‘natto’ led to tRNAGlu cleavage, whereas tRNA3Ser was cleaved in cells expressing wapA-CTT-UB-10 from B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii T-UB-10 (Fig. 5B). In each instance, tRNase activity was specifically blocked by coexpression of the cognate wapI gene (Fig. 5B). Thus, each WapA-CT possesses a distinct tRNase activity capable of inhibiting cell growth.

Fig. 4.

The wapA loci from B. subtilis strains encode different toxin/immunity pairs. B. subtilis wapA-CT/wapI genes encode a network of cognate toxin/immunity pairs. Arabinose-inducible wapA-CT constructs were introduced into E. coli cells expressing various wapI genes and transformants selected on media supplemented with L-arabinose.

Fig. 5.

WapA-CT toxins have diverse tRNase activities. (A) WapA-CT168 is a general tRNase. The PBAD-wapA-CT168 construct was induced with L-arabinose (+) in E. coli cells that coexpress wapI from the indicated strains. RNA was analyzed by Northern blot using probes to the indicated tRNAs. (B) WapA-CTnatto and WapA-CTT-UB-10 toxins are specific tRNases. PBAD-wapA-CT constructs were induced with L-arabinose (+) in E. coli cells that coexpress wapI from the indicated strains. tRNAs were analyzed by Northern blot.

WapA Mediates Intercellular Competition in Bacillus subtilis 168.

Finally, we tested whether WapA mediates intercellular competition. We deleted the wapA-CT/yxxG region from B. subtilis 168 to generate a target strain for coculture with wild-type wapA+ cells. Initially, we conducted competitions in transwell chambers, which separate the two populations with membranes containing either 0.45-µm or 8.0-µm pores. The ∆wapA-CT-∆yxxG targets were inhibited if they could make contact with wapA+ cells but not when segregated from the inhibitors by 0.45-µm pores (Fig. 6A). Moreover, ∆wapA-CT-∆yxxG targets carrying a plasmid-borne copy of yxxG were protected from inhibition (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that this gene is sufficient to confer immunity. WapA-CT variability suggests that this system is modular and can deliver different toxins. To test this hypothesis, we generated chimeric inhibitor strains by replacing the wapA-CT/yxxG coding region in B. subtilis 168 with the corresponding sequences from B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. W23 and B. subtilis subsp. ‘natto’. Both chimeric strains inhibited ∆wapA-CT-∆yxxG target cells, and targets were protected only by cognate wapI immunity genes (Fig. 6B). Together, these results demonstrate that B. subtilis WapA functions like Rhs as a modular contact-dependent inhibition system.

Fig. 6.

WapA functions in intercellular competition. (A) WapA mediates contact-dependent inhibition. Wild-type B. subtilis 168 (wapA+) was cocultured with ∆wapA-CT-∆yxxG targets in a transwell apparatus. Growth chambers were separated by membranes containing 0.45-µm or 8.0-µm pores. Target cells carried plasmid-borne yxxG or vector alone (pHB201) where indicated. (B) WapA is a modular toxin delivery system. Wild-type B. subtilis 168 and chimeric inhibitors expressing wapA-CT/wapI sequences from the indicated B. subtilis strains were cocultured with ∆wapA-CT-∆yxxG targets at a 1:1 ratio. Targets expressed wapI from the indicated B. subtilis strains. The bar at the far left represents mock competition with B. subtilis 168 ∆wapA-CT mutant cells. Target cell growth is expressed as the competitive index as described in Materials and Methods.

Discussion

Rhs elements were discovered more than 30 y ago, but only now are their physiological functions being elucidated. Early studies found that the E. coli rhsA core extension inhibits recovery from stationary phase (17), and recent work suggests that this toxin inhibits protein synthesis (18). Additionally, a plasmid-encoded Rhs protein has been implicated in bacteriocin production in Pseudomonas savastanoi (19). Bioinformatic analyses also support the conclusion that bacterial Rhs proteins commonly carry toxin domains (10, 20). We propose that intercellular growth inhibition is the primary function of these proteins because the distantly related WapA proteins of Bacillus and Listeria species share a similar architecture with Rhs and also deliver toxic C-terminal domains. The divergence of Rhs and WapA probably reflects the different strategies required to deliver protein toxins across Gram-negative and Gram-positive cell envelopes. D. dadantii 3937 appears to use a T6S apparatus to introduce Rhs toxins into target cells. It is unclear whether an entire Rhs protein could be delivered in this process because these systems typically secrete much smaller effector proteins (16). Remarkably, T6SS can inject toxins into a variety of Gram-negative bacteria and eukaryotes (21–23), suggesting that D. dadantii 3937 also may deliver Rhs to other species. On the other hand, WapA carries a canonical secretion signal sequence and is stably associated with the peptidoglycan wall of B. subtilis (8). By analogy with bacteriocins and CDI systems (13, 24), WapA probably binds to cell-surface receptors on target cells and subsequently delivers its C-terminal toxin domain. Such surface receptor–ligand interactions are specific, and therefore we predict that WapA-mediated inhibition is restricted to closely related bacteria. Despite the differences in delivery modalities, Rhs and WapA act only on nearby target cells. Thus, both systems are designed to influence the immediate environment and therefore could serve to establish a niche and defend it against other bacteria. The fact that diverse bacteria possess several distinct systems (CDI, Rhs, and T6SS) to mediate contact-dependent inhibition suggests that this activity is fundamental to bacterial biology.

YD-repeat proteins play an important role in bacterial interactions with eukaryotic host cells. The insecticidal toxin-complex C proteins (TccC) of Photorhabdus luminescens strains contain YD-peptide repeats and have a core/core-extension architecture that is reminiscent of Rhs (25). TccC core extensions carry toxin domains that are used to destroy the midgut of insect hosts. The Serratia entomophila pathogenicity C protein (SepC) shares homology with TccC and very likely has the same insecticidal function (26). Similarly, RhsT (UniProt ID: A6N5U6) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PSE9 recently was shown to be translocated into phagocytic cells, where it induces inflammasome-mediated cell death (27). Kung et al. (27) also showed that mice survive infection with ∆rhsT mutants in an acute pneumonia model, demonstrating that RhsT is a bona fide virulence factor. However, we note that a potential immunity gene lies immediately downstream of rhsT (GenBank ID: EF611305.1). The translation initiation signals for this unannotated gene overlap with the rhsT 3′-coding sequence, which is very similar to the arrangement of other rhs toxin/immunity gene pairs. These observations suggest that P. aeruginosa PSE9 is also a potential RhsT target and needs to protect itself from toxin delivery. Perhaps RhsT is delivered into both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells through a T6S mechanism. Because D. dadantii 3937 is a soft-rot pathogen, it also could deploy Rhs as virulence factors against plant host cells. RhsC may be a good candidate for delivery into plant cells because its gene is linked to a full complement of T6SS genes. Although the biochemical activity of RhsC-CT is unknown, this domain clearly inhibits E. coli and conceivably could exert a similar effect if introduced into plant hosts. We suspect that Rhs evolved to exchange protein toxins between bacteria and that some bacteria have co-opted these systems for a role in pathogenesis.

In addition to their growth-inhibiting function, Rhs also appear to coordinate multicellular behavior. Disruption of an rhs gene in Myxococcus xanthus ablates social motility (28), suggesting a broader role in communication between kin. Perhaps contact-dependent exchange of Rhs-CTs between isogenic/immune cells provides information about population density, analogous to quorum sensing mediated by soluble factors. The toxin/immunity activities may ensure that only isogenic cells are allowed to participate and could exclude “cheaters” who wish to benefit from cooperative behavior but not bear the burden of rhs expression. This general hypothesis is supported by a recent report that CDI is required for robust biofilm formation in Burkholderia thailandensis E264 (29). Thus, immune sibling cells appear to exploit CDI-mediated contact to build a multicellular community. Intercellular communication also is a function of the YD-repeat–containing teneurin proteins of higher metazoans. Teneurins are type II integral membrane proteins that help to establish neuronal cell connections during development (30, 31). Remarkably, some teneurins carry C-terminal sequences that resemble neuroendocrine signaling peptides (32). These sequences are adjacent to predicted furin cleavage sites, suggesting that the C-terminal peptides are released and transmit signals to neighboring cells. The parallels with the bacterial inhibition systems described here are striking and suggest that all YD-repeat proteins share a primordial function in cell–cell contact and communication.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

All bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. D. dadantii 3937 mutants were constructed by allelic exchange as described (33). Briefly, regions upstream and downstream of the target gene were amplified by PCR. The two products then were combined into one fragment by overlapping end-PCR and were ligated into plasmid pRE112 (33). D. dadantii 3937 gene deletions were complemented using the mini-Tn7 delivery plasmid pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T to introduce genes in a single copy at the glmS locus (34). B. subtilis 168 mutants were generated by double-crossover integration using a series of plasmid constructs described in SI Materials and Methods. B. subtilis wapI genes were amplified by PCR and ligated to plasmid pHB201 (35) for analysis of immunity function in B. subtilis 168. Sequences encoding Rhs-CT and WapA-CT toxins and corresponding immunity proteins were amplified by PCR and cloned into derivatives of plasmids pCH450 (36) or pTrc99A for analysis in E. coli cells. Oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table S3, and the details of all plasmid constructions are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Growth Conditions and Competition Assays.

D. dadantii 3937 and B. subtilis strains were routinely grown in LB broth/agar at 30 °C and 37 °C, respectively. When appropriate, medium was supplemented with antibiotics as described in SI Materials and Methods. D. dadantii 3937 competitions were performed on LB agar buffered at pH ∼7.3 with 50 mM potassium phosphate and supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) D-glucose. Inhibitors and targets were mixed at a 10:1 ratio and were plated for coculture at 30 °C. Contact dependence was tested by separating the inhibitor and target cells with membranes as described in SI Materials and Methods. B. subtilis 168 competitions were performed at a 1:1 inhibitor-to-target ratio in shaking LB broth cultures. Contact dependence was determined by coculture in a transwell apparatus as described in SI Materials and Methods. Viable inhibitor and target cells were enumerated as colony-forming units at the beginning and end of coculture by plating on selective media. All competition data are expressed as the competitive index (CI) of target cells: .

.

Microscopy.

Inhibitor and GFP-labeled target cells were cocultured at a 1:1 cell ratio for 12 h. Cells were fixed in 4% (vol/vol) formaldehyde for 12 h, quenched with 125 mM glycine (pH 7.5) for 15 min, and washed with 1× PBS. Bacteria were plated onto glass slides coated with poly-D-lysine and were stained with DAPI supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100. Images were collected and processed with the GIMP imaging suite as described in SI Materials and Methods. Anucleate target cells were quantified by visual inspection of at least 300 target cells from two independent cocultures (∼150 target cells from each biological replicate). Cells were scored as anucleate if they lacked visible DAPI staining.

RNA Analyses.

WapA-CT toxins were expressed in E. coli cells from the arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter. Cells were frozen at −80 °C and extracted with guanidinium isothiocyanate-phenol to isolate total RNA. tRNAs were analyzed by Northern blot hybridization and S1 nuclease protection as described (14, 36). Oligonucleotide probes (Table S3) were radiolabeled with [32P] for northern and S1 protection analyses as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Lindow for pPROBE plasmids and Amy Charkowski for strains and discussions. This work was supported by Grant 0642052 from the National Science Foundation (to D.A.L.) and by National Institutes of Health Grants U54 AI065359 (to D.A.L.) and R01 GM078634 (to C.S.H.). S.K. is supported by fellowships from the Carl Tryggers and Wenner-Gren Foundations.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1300627110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lin RJ, Capage M, Hill CW. A repetitive DNA sequence, rhs, responsible for duplications within the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. J Mol Biol. 1984;177(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill CW, Sandt CH, Vlazny DA. Rhs elements of Escherichia coli: A family of genetic composites each encoding a large mosaic protein. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12(6):865–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson AP, Thomas GH, Parkhill J, Thomson NR. Evolutionary diversification of an ancient gene family (rhs) through C-terminal displacement. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:584. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao S, Hill CW. Reshuffling of Rhs components to create a new element. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(5):1393–1398. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1393-1398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K, Knabel SJ, Dudley EG. rhs genes are potential markers for multilocus sequence typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(18):5853–5862. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00859-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker RP, Beckmann J, Leachman NT, Schöler J, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Phylogenetic analysis of the teneurins: Conserved features and premetazoan ancestry. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(3):1019–1029. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minet AD, Rubin BP, Tucker RP, Baumgartner S, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Teneurin-1, a vertebrate homologue of the Drosophila pair-rule gene ten-m, is a neuronal protein with a novel type of heparin-binding domain. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 12):2019–2032. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.12.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster SJ. Molecular analysis of three major wall-associated proteins of Bacillus subtilis 168: Evidence for processing of the product of a gene encoding a 258 kDa precursor two-domain ligand-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8(2):299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen L, Bollback JP, Dimmic M, Hubisz M, Nielsen R. Genes under positive selection in Escherichia coli. Genome Res. 2007;17(9):1336–1343. doi: 10.1101/gr.6254707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole SJ, et al. Identification of functional toxin/immunity genes linked to contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) and rearrangement hotspot (Rhs) systems. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(8):e1002217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki SK, et al. A widespread family of polymorphic contact-dependent toxin delivery systems in bacteria. Nature. 2010;468(7322):439–442. doi: 10.1038/nature09490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aoki SK, et al. Contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli. Science. 2005;309(5738):1245–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoki SK, et al. Contact-dependent growth inhibition requires the essential outer membrane protein BamA (YaeT) as the receptor and the inner membrane transport protein AcrB. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70(2):323–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diner EJ, Beck CM, Webb JS, Low DA, Hayes CS. Identification of a target cell permissive factor required for contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) Genes Dev. 2012;26(5):515–525. doi: 10.1101/gad.182345.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGinness KE, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Engineering controllable protein degradation. Mol Cell. 2006;22(5):701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD. Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:453–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlazny DA, Hill CW. A stationary-phase-dependent viability block governed by two different polypeptides from the RhsA genetic element of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(8):2209–2213. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2209-2213.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aggarwal K, Lee KH. Overexpression of cloned RhsA sequences perturbs the cellular translational machinery in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(18):4869–4880. doi: 10.1128/JB.05061-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sisto A, et al. An Rhs-like genetic element is involved in bacteriocin production by Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2010;98(4):505–517. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyer LM, Zhang D, Rogozin IB, Aravind L. Evolution of the deaminase fold and multiple origins of eukaryotic editing and mutagenic nucleic acid deaminases from bacterial toxin systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(22):9473–9497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hood RD, et al. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacIntyre DL, Miyata ST, Kitaoka M, Pukatzki S. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(45):19520–19524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012931107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng J, Ho B, Mekalanos JJ. Genetic analysis of anti-amoebae and anti-bacterial activities of the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cascales E, et al. Colicin biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(1):158–229. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00036-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waterfield NR, Bowen DJ, Fetherston JD, Perry RD, ffrench-Constant RH. The tc genes of Photorhabdus: A growing family. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9(4):185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)01978-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurst MR, Glare TR, Jackson TA, Ronson CW. Plasmid-located pathogenicity determinants of Serratia entomophila, the causal agent of amber disease of grass grub, show similarity to the insecticidal toxins of Photorhabdus luminescens. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(18):5127–5138. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5127-5138.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kung VL, et al. An rhs gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a virulence protein that activates the inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(4):1275–1280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109285109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Youderian P, Hartzell PL. Triple mutants uncover three new genes required for social motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Genetics. 2007;177(1):557–566. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson MS, Garcia EC, Cotter PA. The Burkholderia bcpAIOB genes define unique classes of two-partner secretion and contact dependent growth inhibition systems. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(8):e1002877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong W, Mosca TJ, Luo L. Teneurins instruct synaptic partner matching in an olfactory map. Nature. 2012;484(7393):201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature10926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosca TJ, Hong W, Dani VS, Favaloro V, Luo L. Trans-synaptic Teneurin signalling in neuromuscular synapse organization and target choice. Nature. 2012;484(7393):237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenzelmann D, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Tucker RP. Teneurins, a transmembrane protein family involved in cell communication during neuronal development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64(12):1452–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7108-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards RA, Keller LH, Schifferli DM. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene. 1998;207(2):149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi KH, et al. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat Methods. 2005;2(6):443–448. doi: 10.1038/nmeth765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bron S, et al. Protein secretion and possible roles for multiple signal peptidases for precursor processing in bacilli. J Biotechnol. 1998;64(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(98)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes CS, Sauer RT. Cleavage of the A site mRNA codon during ribosome pausing provides a mechanism for translational quality control. Mol Cell. 2003;12(4):903–911. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.