Abstract

Irisin is a recently identified myokine secreted from the muscle in response to exercise. In the rats and mice, immunohistochemical studies with an antiserum against irisin peptide fragment (42–112), revealed that irisin-immunoreactivity (irIRN) was detected in three types of cells; namely, skeletal muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Tissue sections processed with irisin antiserum pre-absorbed with the irisin peptide(42–112) (1 μg/ml) showed no immunoreactivity. Cerebellar Purkinje cells were also immunolabeled with an antiserum against fibronectin type II domain containing 5 (FNDC5), the precursor protein of irisin. Double-labeling of cerebellar sections with irisin antiserum and glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) antibody showed that nearly all irIRN Purkinje cells were GAD-positive. Injection of the fluorescence tracer Fluorogold into the vestibular nucleus of the rat medulla retrogradely labeled a population of Purkinje cells, some of which were also irIRN. Our results provide the first evidence of expression of irIRN in the rodent skeletal and cardiac muscle, and in the brain where it is present in GAD-positive Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Our findings together with reports by others led us to hypothesize a novel neural pathway, which originates from cerebellum Purkinje cells, via several intermediary synapses in the medulla and spinal cord, and regulates adipocyte metabolism.

Keywords: Purkinje cells, vestibular nucleus, thermogenesis, cardiomyocyte, glutamate decarboxylase, rostral ventrolateral medulla

1. Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) is a transcriptional coactivator regulating gene in response to metabolic and/or neuroendocrine signals (Finck and Kelly, 2006). Exercise, particularly chronic, is associated with increased expression of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle; whereas, type 2 diabetes or a sedentary lifestyle is correlated with a reduced expression (Handschin and Spiegelman, 2008). Increased PGC-1α expression protects against weight gain, inflammation, oxidative stress, muscle wasting and bone loss (Wenz et al., 2009). The molecule(s) that conveys the signal from PGC-1α to the target cell, however, has yet to be firmly identified.

A recent report by Boström et al. (2012) shows in mice that over-expression of PGC-1α induced a brown-like adipose tissue gene program, including uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) expression, in white adipose tissue, which can also be induced by free wheel running exercise. Moreover, the observation that subcutaneous adipocytes treated with medium from muscle cells expressing PGC-1α, had a similar response, raises the possibility that a secreted substance from muscle cells over-expressing PGC-1α may be responsible for browning of white adipocyte tissues (Boström et al., 2012). Profiling of muscle genes activated by PGC-1α identified a factor termed fibronectin type III domain containing 5 (FNDC5) with predicted structural features of a type I membrane protein that could be proteolytically cleaved to release a smaller protein, which was subsequently named irisin, into the blood stream (Boström et al., 2012). Several observations support the contention that irisin may be the signaling molecule. First, exercise-induced FNDC5 gene expression in muscles was accompanied by a parallel increase in the concentration of circulating irisin. Second, irisin activated oxygen consumption and thermogenesis of the fat cells in culture. Third, injection of an adenoviral vector over-expressing irisin into mice resulted in browning of subcutaneous white fat and increased total body energy expenditure. These results support the model that exercise induces muscle FNDC5 expression. The latter increases the amount of circulating irisin, which in turn, activates adipocyte thermogenic programs, leading to mitochondrial heat production and energy expenditure (Boström et al., 2012).

While FNDC5 is detected in skeletal muscle (Boström et al., 2012), the cellular distribution of irisin has not been established. Further, FNDC5 is expressed in the adult rodent heart and brain (Ferrer-Martínez et al., 2002). Immunohistochemical studies were undertaken with the aim to identify the type(s) of cells expressing irisin in the rat and mouse brain and musculature.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1 Experimental animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 gm) and ICR mice (25–30 gm) were used in this study. Experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Design of irisin antigen

The selection of the fragment irisin(42–112) as the antigen to immunize the rabbits was based on the following considerations. First, the region of irisin(1–44) is absent from the human FNDC5 isoform 3 (Q8NAU1-3) and 4 (Q8NAU1-4); but, both are protein transcripts that begin with irisin(45–112) to the C-terminal end of FNDC5. Second, when modeling the protein using the Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) bioinformatics, the residues of irisin(39–42), QKKD, are the transition sequences between the protein domain 1 and protein domain 2 (Krogh et al.,1994), raising the possibility that irisin(42–112) being the functional domain capable of turning on the UCP1 gene. Lastly, both the isoform 4 of FNDC5 and the 112 residues of irisin have the same bioactivity in activating the CD137 positive beige precursor cells which, in turn, trigger UCP1 gene expression (see Fig. 4C of Wu et al., 2012). The overlapping region of these two proteins is that of irisin(45–112), which may serve a key function in turning on the UCP1 gene expression. From the MASS Spectrometry analysis, we have detected the presence of irisin derived peptide that was possibly cleaved from irisin between K41 and residue D42. Therefore, our design for an antibody specifically recognized the antigen containing three residues of corresponding sequences, DVR, at the N-terminal side, in addition to irisin(45–112). The specificity of the antibody against the entire sequence of irisin and irisin(42–112) was later confirmed by the enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and radioimmunoassay. For these reasons, the fragment irisin(42–112) was selected as the surrogate of irisin in our study.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Rats and mice anesthetized with 4% isofurane were intracardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains, hearts and gastrocnemius were removed, postfixed for 2 h, and stored in 30% sucrose/PBS overnight.

In single staining, tissues were processed for irIRN by the avidin-biotin complex procedure (Dun et al., 2006; 2010). Tissues were first treated with 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase, washed several times, blocked with 10% normal goat serum, and incubated in irisin-antiserum (1:700 dilution; a rabbit polyclonal against the human C-terminus irisin fragment (42–112); Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA). The amino acid sequence of 112 residues portion of irisin is identical in human (uniprot:Q8NAU1-1 and Q8NAU1-2 ), rat (uniprot:Q8K3V5), and mouse (uniprot:Q8K4Z2) (Ota et al., 2004). Cross-reactivity of irisin-antiserum against several peptides was evaluated by EIA. Irisin-antiserum showed 100% cross-reactivity with the following peptides: irisin (human, rat, mouse), irisin (42–112) (human, rat, mouse); 9% cross-reactivity was noted with FNDC5 isoforms 4 (Q8NAU1-4) (human), and no cross-reactivity against FNDC5 (162–209) (rat, mouse) and irisin (42–95) (human, rat, mouse).

Heart and gastrocnemius were sectioned horizontally or transversely. Coronal sections of 50 μm were prepared from the brain. After thorough rinsing, sections were incubated in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:100 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 h and rinsed with PBS and incubated in avidin-biotin complex solution for 1.5 h (1:100 dilution; Vector Laboratories). After several washes in Tris-buffered saline, sections were developed in 0.05% diaminobenzidine/0.001% H2O2 solution and washed for at least 2 h with Tris-buffered saline. Sections were mounted on slides with 0.25% gel alcohol, air dried, dehydrated with absolute alcohol followed by xylene, and coverslipped with Permount.

With respect to FNDC5 immunoreactivity (irFNDC5), cerebellar sections from rats and mice were incubated in a rabbit polyclonal antiserum directed against FNDC5 C-terminal fragment (149–196) (1:2,000, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc.). The immunostaining procedure was similar to that described for irisin. The FNDC5 antibody exhibits no cross-reactivity with irisin, but recognizes the intact recombinant protein FNDC5 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.).

For control experiments, cerebellar and muscle sections were processed with irisin- or FNDC5-antiserum pre-absorbed with the irisin peptide fragment (42–112) (1μg/ml) or FNDC5 peptide fragment (149–196) (mouse, rat) (1μg/ml) overnight.

2.4. Immunofluorescence procedures

In the case of double-labeling experiments, immunofluorescent techniques were applied (Dun et al., 2010). Cerebellar sections were first incubated with irisin antiserum (1:500 dilution) and then with GAD65 antibody (1:300 dilution, a mouse monoclonal, Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA). The GAD65 monoclonal antibody has been shown to label Purkinje cells of the rat cerebellum, albeit cell bodies were less intensely labeled as compared to that labeled with GAD67 antibody (Esclapez et al., 1994). Sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antiserum conjugated to either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or Texas Red, and examined under a confocal scanning laser microscope (Leica TCS SP5) with excitation wavelengths set to 488 nm for FITC and 561 nm for Texas Red in the sequential mode.

2.5. Microinjection of Fluorogold to the vestibular nucleus of rat medulla

Purkinje cells in the cerebellum project some of their axons to the vestibular nucleus of the medulla in several species (Carleton and Carpenter, 1983; De Zeeuw and Berrebi, 1995). Retrograde tract tracing experiments were performed to determine whether irIRN Purkinje cells project their axons to the vestibular nucleus. Rats (n=6) anesthetized with 4% isofurane were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) and under a heat lamp. Aseptic conditions were maintained during the surgical procedure. The stereotaxic coordinates for microinjection to the vestibular nuclei were as follows: 10.8 to 11.5 mm caudal from the bregma, 1.5 to 2.0 mm lateral from the midline and 6.6–8.0 mm deep from the surface of cerebellum (Paxions and Watson, 1998). Each rat received an injection of 15 nl 4% Fluorogold solution along the rostro-caudal axis of the vestibular nucleus. Five days later, rats were anesthetized with 4% isofurane and intracardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde fixative. Brains were removed and processed for irisin Texas Red fluorescence, as described above. In an effort to enhance the fluorescent intensity of Fluorogold, cerebellar sections were incubated in anti-Fluorogold antiserum (1:500; Chemicon), washed and then incubated in secondary antiserum conjugated to FITC.

2.6. Cell counting

Viewed under 20x objective, the number of irIRN and irGAD cells from 15 randomly selected cerebellar sections from 3 rats doubled-labeled with irisin-antiserum and GAD-antibody was counted. Similarly, the number of irIRN and Fluorogold cells was counted in 15 cerebellar sections from 3 rats to which 15 nl 4% Fluorogold solution was microinjected to the vestibular nucleus.

3. Results

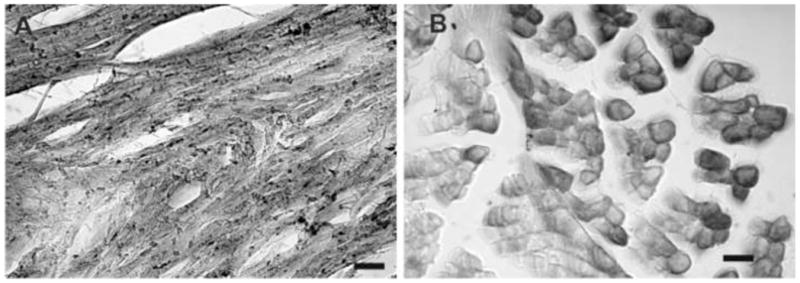

3.1. Irisin immunoreactivity in murine skeletal and cardiac muscle

Transverse or horizontal sections prepared from the gastrocneimus and hearts (n=6) showed that irIRN of varying intensities could be detected in the majority of cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 1A and 1B). As shown in the cross-sections of mouse skeletal muscle cells, irIRN appeared to be concentrated on or immediately adjacent to the cell membrane, with a lower immunoreactivity toward the center of muscle fibers (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Cross sections of mouse cardiac and skeletal muscle fibers labeled with irisin antiserum. A and B, cardiac and skeletal muscle cells express varying intensities of irIRN. In skeletal muscle fibers, irIRN appears to be more densely localized to the cell membrane, with lower immunoreactivity close to the middle of muscle cells. Scale bar: 50 μm.

3.2. Irisin immunoreactivity in the rat and mouse brain

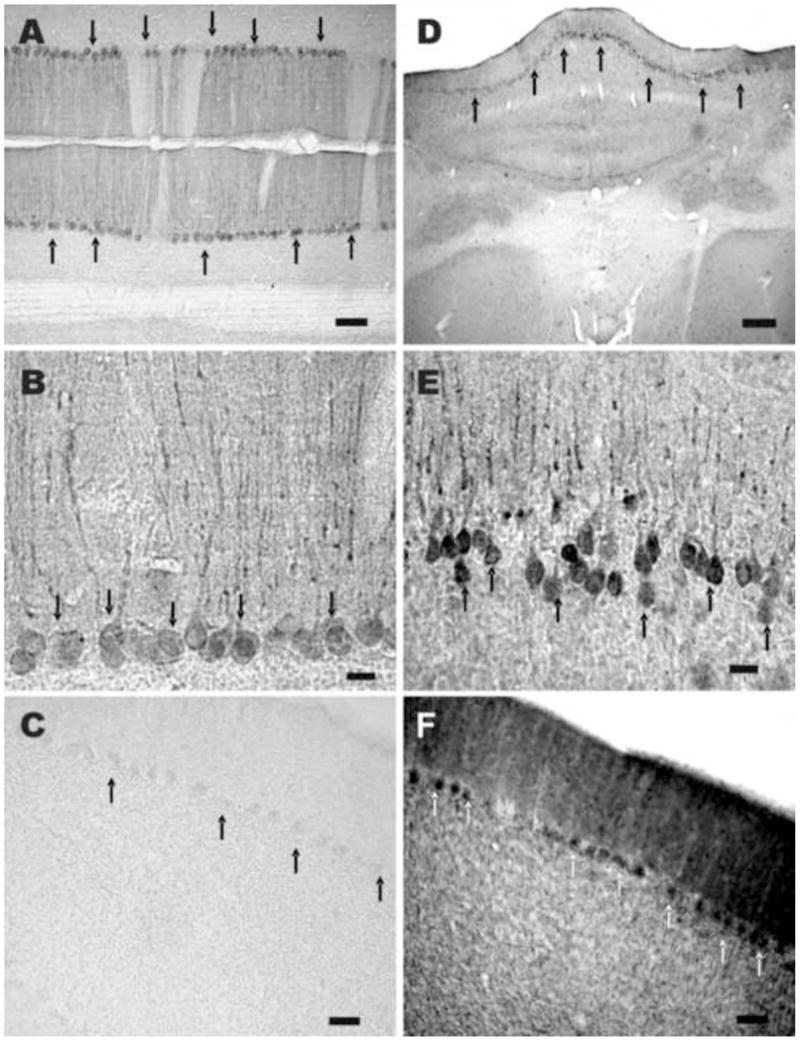

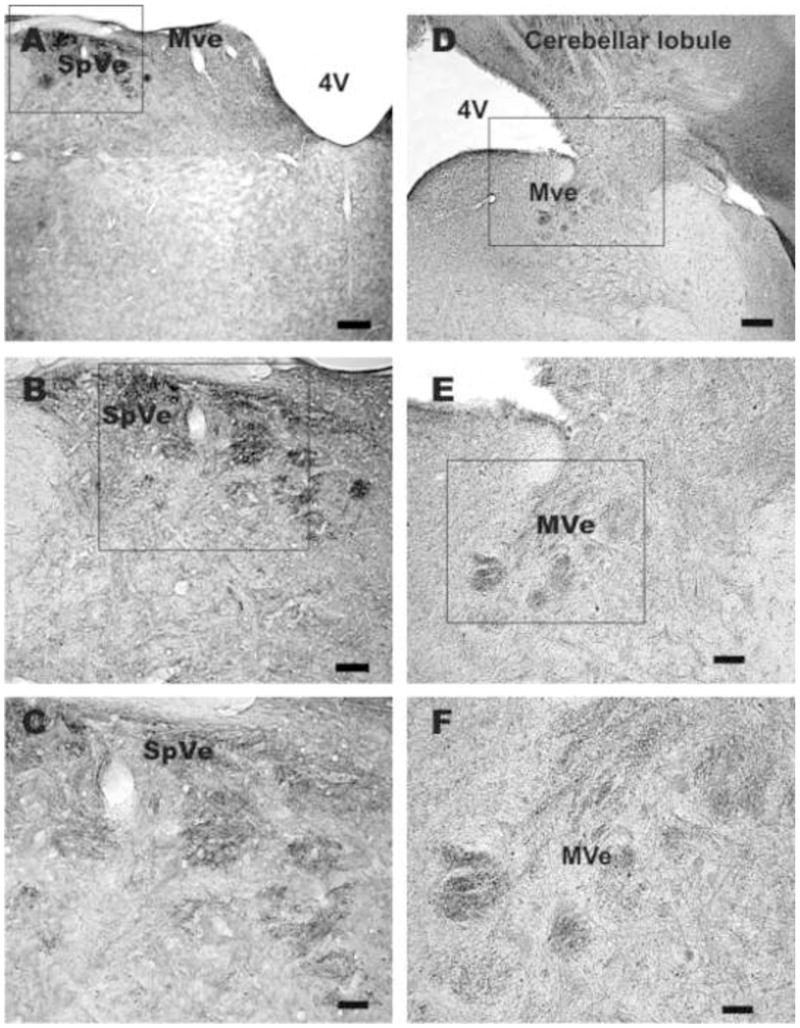

Examination of every five sections taken between the frontal lobe and the caudal medulla of rat (n=6) and mouse (n=4) brains revealed that irIRN was present only in Purkinje cells of the rat cerebellum (Fig. 2A and 2B) and mouse cerebellum (Fig. 2D and 2E) and in cell processes distributed to the vestibular nuclei of the medulla oblongata (Fig. 3A–F). Clusters of irIRN cell processes were distributed throughout the four subdivisions of the vestibular nucleus: superior, lateral, medial and inferior. Fig. 3 shows irIRN cell processes in the superior and medial vestibular nuclei. Immunoreactive cells or cell processes were not detectable in other areas of the brain or the spinal cord of the rats and mice. Thus, the pattern of distribution of irIRN was similar in the rat and mouse brains.

Fig. 2.

Rat and mouse cerebellar sections labeled with irisin antiserum, irisin antiserum pre-absorbed with the peptide or FNDC5-antiserum. A and B, a section of rat cerebellum where only Purkinje cells and their axons are labeled, arrows indicate several irIRN Purkinje cells. C, a section of rat cerebellum labeled with irisin antiserum pre-absorbed with the peptide irisin (42–11) (1 μg/ml) overnight; irIRN is not detected in Purkinje cells; several of which are indicated by arrows. D and E, a section of mouse cerebellum where irIRN is detected in Purkinje cells and their axons. F, a section of rat cerebellum labeled with FNDC5-antiserum, where Purkinje cells were positively labeled; several of which are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: A, 100 μm; B and E, 25 μm; C and F, 50 μm; D, 250 μm.

Fig. 3.

Sections of rat medulla labeled with irisin antiserum. A, several bundles of irIRN cell processes in the superior vestibular nucleus (SpVe); fewer cell processes are noted in the medial vestibular nucleus (MVe). B and C, higher magnifications of A, varicose irIRN cell processes are detected in the SpVe. D, a medullary section where several bundles of irIRB cell processes are noted in the medial vestibular nucleus (MVe); which connects to the cerebellar lobule via the inferior cerebellar peduncle (box square). E and F, higher magnifications of the boxed area in D; irIRN cell processes with bead-like appearance are seen in the MVe. Scale bar: A and D, 250 μm; B and E, 100 μm; C and F, 50 μm.

Control studies were carried out in which cerebellum or muscle specimen were incubated in irisin antiserum pre-absorbed with the peptide irisin(42–112) (1 μg/ml). Under these conditions, irIRN was not detectable in any of the tissue sections; a representative control section of rat cerebellum, where irIRN was absent in Purkinje cells, is illustrated in Fig. 2C.

3.3. FNDC5 immunoreactivity in the rat brain

Similar to irIRN, cerebellar sections from three rats processed with FNDC5 antiserum revealed that Purkinje cells were immunoreactive to FNDC5 (Fig. 2F). Cerebellar sections processed with FNDC5 antiserum pre-absorbed with the FNDC5(149–196) peptide (1μg/ml) showed no positively labeled cells (not shown).

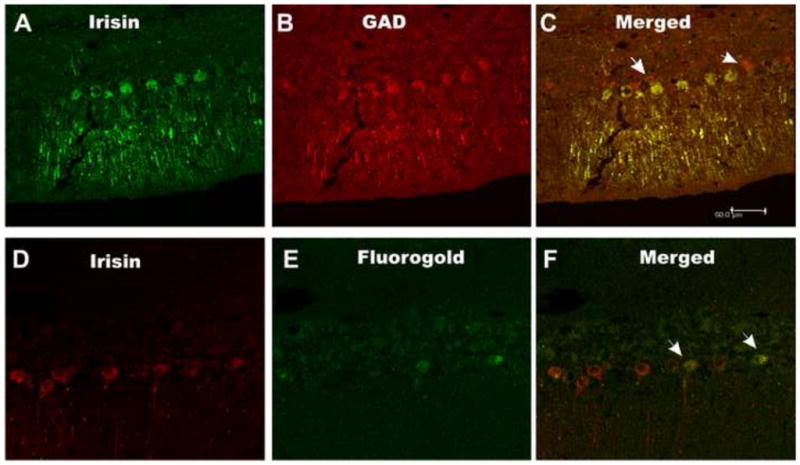

3.4. Expression of irisin- and GAD-immunoreactivity in murine cerebellar Purkinje cells

Purkinje cells of the cerebellum contain GAD, the enzyme that catalyses the conversion of glutamate to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Saito et al., 1974). Hence, GAD can be a biomarker for GABA-containing cells. Double-labeling the cerebellar sections from rats (n=3) and mice (n=3) with irisin antiserum and GAD antibody revealed that nearly all irIRN Purkinje cells were GAD-positive, but not vice versa (Fig. 4A–C). The number of irIRN and irGAD Purkinje cells obtained from 15 randomly selected cerebellar sections double-labeled with anti-IRN and anti-GAD antiserum was 633 and 672, respectively, representing approximately 94% of irGAD Purkinje cells expressing irIRN.

Fig. 4.

Rat cerebellar sections double-labeled with irisin antiserum and GAD antibody or retrogradely labeled with Fluorogold. A, a cerebellar section containing several irIRN Purkinje cells. B, same section as A, where several GAD positive Purkinje cells are detected. C, a merged image of A and B, where Purkinje cells with yellowish red color are indicative of co-expression of irIRN and GAD; two GAD positive cell (arrows) that are not labeled with irIRN. D and E, a cerebellar section where two of the irIRN cells (D) are Fluorogold positive (E); F, a merged image where two of the irIRN cells are also Fluorogold containing, as indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 50 μm.

3.5. Retrograde labeling of Purkinje cells of the rat

Purkinje cells send their axons to target neurons within or outside of the cerebellum, including neurons in the vestibular nucleus of the rat (De Zeeuw and Berrebi, 1995), cat and monkey (Carleton and Carpenter, 1983). Here, microinjection of the retrograde tracer Fluorogold to subdivisions of the vestibular nucleus: i.e., superior vestibular nucleus (SVe), lateral vestibular nucleus (LVe), medial vestibular nucleus (MVe) and inferior vestibular nucleus (IVe) (n=4), resulted in the retrograde labeling of cerebellar Purkinje cells; some of which also expressed irIRN; a representative cerebellar section where two of the irIRN cells were also Fluorogold-positive, is shown in Fig. 4D–F. The number of irIRN cells and Fluorogold-positive cells obtained from 15 randomly selected cerebellar sections was 562 and 284, indicating about 50% of irIRN cells were retrogradely labeled by Fluorogold microinjected into the vestibular nucleus.

4. Discussion

With the use of an antiserum directed against the C-terminus of irisin peptide fragment (42–112), our result shows that irIRN is present in three types of cells; namely, skeletal muscle, cardiomyocytes and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. This pattern of distribution is similar in rats and mice. The irisin-antiserum appears to be specific, as pre-absorption of the antiserum with the irisin peptide(42–112) resulted in no immunoreactivity in any of the tissue sections examined.

Irisin is proposed to be the secreted product of FNDC5, which is highly expressed in the mouse (Boström et al., 2012; Lecker et al., 2012) and human (Huh et al., 2012) muscle cells. In our study, nearly all muscle fibers, regardless skeletal or cardiac, expressed varying intensities of irIRN; the highest being associated with the cell membrane. This observation appears to be consistent with the report that FNDC5 is associated with mouse muscle membrane (Boström et al., 2012). A recent study utilizing quantitative real-time PCR reports that among 47 different human tissues assayed, skeletal muscle has the highest amount of FNDC5, which is taken as 100%; the pericardium, heart and brain is about 80%, 20% and 5% of the amount expressed in the muscle; peripheral tissues, such as liver, pancreas, kidney, etc., express little or no FNDC5 mRNA (Huh et al., 2012). Results from an earlier study, on the other hand, show that the adult rat brain expressed a high level of FNDC5 mRNA (Ferrer-Martínez et al., 2002). The discrepancy may be related to different areas of the brain where tissue FNDC5 mRNA was assayed.

Irisin is proposed to serve as a circulating myokine to increase thermogenesis, improve obesity and glucose homeostasis (Boström et al., 2012). A more recent study, on the other hand, fails to establish a positive correlation between the plasma concentration of several signaling molecules including irisin, and calorie restriction-related improvement in insulin sensitivity (Sharma et al., 2012). Hence, the physiological role of irisin as it relates to energy metabolism remains to be established. Moreover, our study shows that the heart may serve as another source of irisin, as the latter is detectable in cardiomyocytes. FNDC5 mRNA, the precursor of irisin, has been reported in the adult rat heart (Ferrer-Martínez et al., 2002). At present, it is not known whether or not irisin associated with the cardiomyocyte is processed in a manner similar to that found in the skeletal muscle. The physiological function of cardiac irisin also remains to be determined.

In addition to the skeletal muscle and heart, our result demonstrates that irIRN is expressed in a population of central neurons, namely, Purkinje cells of the cerebellum and their cell processes projecting to the vestibular nucleus of the medulla. With an antiserum directed against the FNDC5 C-terminal fragment (149–196), Purkinje cells of the cerebellum were shown to be irFNDC5. This observation supports the hypothesis that irisin is derived from FNDC5 in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. The possibility that other types of neurons may express irIRN and/or irFNDC5 in quantity below detection limit by our antibody cannot be dismissed. Purkinje cells, a type of neurons found in the Purkinje layer of the cerebellar cortex, are arranged in such a way that one is stacked in front of the other, giving a characteristic layer-like appearance. Cells that were irIRN or irFNDC5 were arranged in such a manner in both the rat and mouse cerebellum. Purkinje cells contain the GABA synthesizing enzyme GAD, therefore, are GABAergic (Chan-Palay et al., 1979). Double-labeling studies show that nearly all irIRN cells were GAD-positive, supporting the contention that irIRN cells are indeed GABA-expressing Purkinje cells. Cerebellar Purkinje cells are not all GABA-containing; for example, some of the Purkinje cells express motilin-like immunoreactivity, with no evidence of GAD (Chan-Palay et al.,1981). Viewed in this context, irIRN Purkinje cells may constitute a sub-population of cerebellar Purkinje cells.

Purkinje cells send their projections to the deep cerebellar nuclei and to the vestibular nucleus (Chan-Palay et al., 1979; De Zeeuw and Berrebi, 1995). Here, microinjection of the retrograde tracer Fluorogold to the vestibular nucleus labeled a population of Purkinje cells, some of which were also irIRN, further supporting the concept that some of the irIRN Purkinje cells innervate the vestibular nucleus. The number of Fluorogold containing irIRN cells was relatively small as compared to the number of irIRN cells (284 vs 562). The vestibular nucleus is an elongated structure, measuring over 3 mm rostro-caudally in an adult rat (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). It is possible that Fluorogold injected into one division of the vestibular nucleus may not reach irIRN axonal terminals distributed to other divisions, contributing to a lower percentage of Fluorogold containing irIRN cells.

A functional role of irisin in the cerebello-vestibular projection is presently not known. Purkinje cells being GABAergic in nature, send inhibitory projections to the deep cerebellar nuclei and vestibular nucleus, and constitute the sole output of all motor coordination in the cerebellar cortex. The major functions of this system include perceptual, ocular motor, coordination of the head and trunk movement, postural and vegetative functions, as well as, navigation and spatial memory (Dieterich and Brandt, 2008). Conversely, loss of Purkinje cells may cause severe cerebellar dysfunction such as dizziness, vertigo, disequilibrium, and ataxia which is an inability to coordinate voluntary muscle movements resulting in nystagmus of the eyes, uncoordinated movement of the limbs, and unsteady or staggering gait (Wang and Zoghbi, 2001; Taroni and DiDonato, 2004). Viewed in this context, irisin may function as a signaling molecule in coordinating body and head movement, particularly during exercise.

In addition to motor function, retrograde and antegrade tract tracing studies show that neurons in the vestibular nucleus, particularly the caudal vestibular nuclei, project their axons directly to rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), with a minor projection to the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) (Holstein et al., 2011). Neurons in the CVLM and RVLM are an integral component of the medullary sympathetic circuitry and project their axons to spinal sympathetic premotor neurons; the latter, via sympathetic postganglionic neurons, may regulate adipose tissue thermogenesis (Morrison et al., 2012). The neurally mediated thermogenic effect of irisin most likely arises either from an increased responsiveness of the adipose tissue to its normal sympathetic nerve input or by enhancing the sympathetic input to brown adipose tissue.

5. Conclusion

Immunohistochemical results demonstrate the expression of irisin immunoreactivity in three types of cells: skeletal, cardiac muscle, and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Irisin is likely to be released from muscles and serves as either a myokine to a multitude of target cells or a paracrine affecting the activity of neighboring cells. A functional role of irisin in the cerebellum has yet to be identified.

Highlights.

Detection of irisin immunoreactivity in skeletal muscle and cardiomyocyte

Presence of irisin immunoreactivity in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum

Co-expression of irisin immunoreactivity and glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) immunoreactivity in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum

Hypothetical neurocircuitry connecting the cerebellum to the fat tissue that may regulate adipocyte metabolism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant HL51314 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- EIA

Enzyme-linked immunoassay

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- FNDC5

fibronectin type III domain containing 5

- irFNDC5

FNDC5 immunoreactivity

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IVe

inferior vestibular nucleus

- irIRN

irisin-immunoreactivity

- GAD

glutamate decarboxylase

- LVe

lateral vestibular nucleus

- Mve

medial vestibular nucleus

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SVe

superior vestibular nucleus

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contribution statement: SLD, RML, YHC, JKC, JJL and NJD designed and performed the experiments. SLD, YHC, RML, JKC, JJL and NJD analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Boström EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton SC, Carpenter MB. Afferent and efferent connections of the medial, inferior and lateral vestibular nuclei in the cat and monkey. Brain Res. 1983;278:29–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Palay V, Palay SL, Wu J-Y. Gamma-aminobutyric acid pathways in the cerebellum studied by retrograde and anterograde transport of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody after in vivo injections. Anat and Embry (Berl) 1979;157:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00315638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Palay V, Nilaver G, Palay SL, Beinfeld MC, Zimmerman EA, Wu JY, O’Donohue TL. Chemical heterogeneity in cerebellar Purkinje cells: existence and coexistence of glutamic acid decarboxylase-like and motilin-like immunoreactivities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7787–7791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw CI, Berrebi AS. Postsynaptic targets of Purkinje cell terminals in the cerebellar and vestibular nuclei of the rat. Euro J Neurosci. 1995;7:2322–2333. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich M, Brandt T. Functional brain imaging of peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Brain. 2008;131:2538–2552. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun SL, Brailoiu E, Wang Y, Brailoiu GC, Liu-Chen LY, Yang J, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Insulin-like peptide 5: expression in the mouse brain and mobilization of calcium. Endocrinol. 2006;147:3243–3248. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Tica AA, Yang J, Chang JK, Brailoiu E, Dun NJ. Neuronostatin is co-expressed with somatostatin and mobilizes calcium in cultured rat hypothalamic neurons. Neurosci. 2010;166:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esciapez M, Tillakaratne NJK, Kaufman DL, Tobin AJ, Houser CR. Comparative localization of two forms of glutamic acid decarboxylase and their mRNAs in rat brain supports the concept of functional differences between the forms. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1834–1865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Martínez A, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR. Mouse PeP: a novel peroxisomal protein linked to myoblast differentiation and development. Dev Dynamics. 2002;224:154–167. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck BN, Kelly DP. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:615–622. doi: 10.1172/JCI27794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. The role of exercise and PGC1alpha in inflammation and chronic disease. Nature. 2008;454:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein GR, Friedrich VL, Jr, Kang T, Kukielka E, Martinelli GP. Direct projections from the caudal vestibular nuclei to the ventrolateral medulla in the rat. Neurosci. 2011;175:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh JY, Panagiotou G, Mougios V, Brinkoetter M, Vamvini MT, Schneider BE, Mantzoros CS. FNDC5 and irisin in humans: I. Predictors of circulating concentrations in serum and plasma and II. mRNA expression and circulating concentrations in response to weight loss and exercise. Metabolism. 2012;61:1725–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Browny M, Mianx IS, Sjőlander K, Haussler D. Hidden Markov Models in Computational Biology: Applications to Protein Modeling. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1501–1531. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecker SH, Zavin A, Cao P, Arena R, Allsup K, Daniels KM, Joseph J, Schulze PC, Forman DE. Expression of the irisin precursor FNDC5 in skeletal muscle correlates with aerobic exercise performance in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Failure. 2012 Sep 20; doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.969543. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF, Madden CJ, Tupone D. Central control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Front Endocrinol. 2012;3:5. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T, Sugiyama T, Irie R, Wakamatsu A, et al. Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs. Nat Genet. 2004;36:40–45. doi: 10.1038/ng1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4. Academic Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Barber R, Wu J, Matsuda T, Roberts E, Vaughn JE. Immunohistochemical localization of glutamate decarboxylase in rat cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:269–273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Castorena CM, Cartee GD. Greater insulin sensitivity in calorie restricted rats occurs with unaltered circulating levels of several important myokines and cytokines. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012 Oct 15;9(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-90. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taroni F, DiDonato S. Pathways to motor incoordination: the inherited ataxias. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:641–655. doi: 10.1038/nrn1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang VY, Zoghbi HY. Genetic regulation of cerebellar development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:484–491. doi: 10.1038/35081558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenz T, Rossi SG, Rotundo RL, Spiegelman BM, Moraes CT. Increased muscle PGC-1α expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20405–20410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911570106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012 Jul 20;150(2):366–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. Epub 2012 Jul 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]