SUMMARY

Cellular disturbances that cause accumulation of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lead to a condition referred to as “ER stress” and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), a signaling pathway that attempts to restore ER homeostasis. The complexity of UPR signaling can generate adaptive and apoptotic outputs, depending on the nature and duration of the ER stress. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small non-coding RNAs that typically repress gene expression, have recently emerged as key gene regulators of the pro-adaptive/pro-apoptotic molecular switch emanating from the ER. Importantly, select miRNAs have been shown to directly regulate key UPR components.

INTRODUCTION

Microribonucleic acids (miRNAs) are short, ~22 nucleotide (nt), single-stranded RNAs that typically exert post-transcriptional control of gene activity [1]. First described in the early 1990s through analysis of temporal control of postembryonic development in C. elegans [2,3], miRNAs began attracting significant attention in 2001 when numerous endogenously expressed miRNAs were identified in worms, flies and mammals [4–7]. A wealth of research, coupled with advances in high throughput sequencing, has revealed that miRNAs represent a sizeable class of regulators which outnumbers kinases and phosphatases [8]. Indeed, over 60% of human protein-coding genes are predicted targets of miRNA-mediated modulation of mRNA stability and/or translation potential [9].

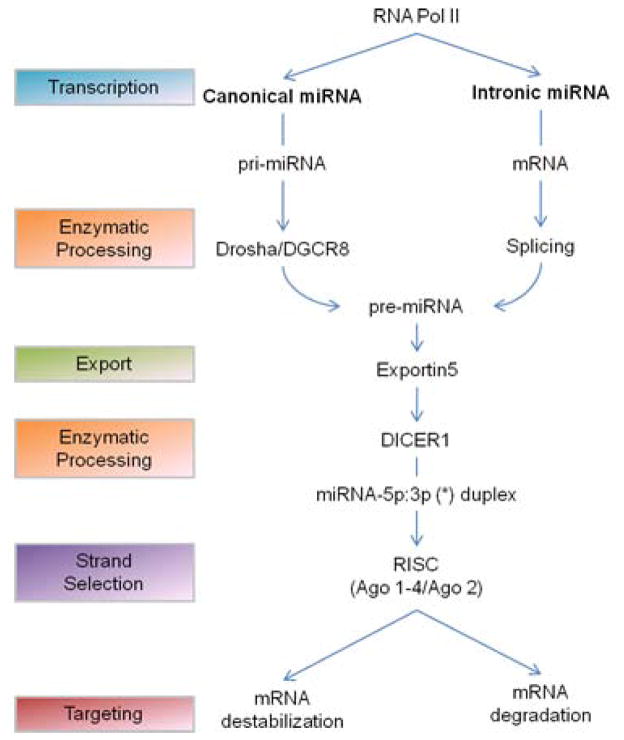

Expression of miRNAs is transcriptionally regulated, with the majority of miRNA genes encoded by RNA-polymerase II-transcribed genes and approximately one-third of known miRNAs embedded within introns of protein-coding genes [10]. In some cases, miRNAs are expressed and function as clusters, whereas many miRNAs act individually. Transcribed miRNAs are enzymatically processed in the nucleus by either the RNase III-type endonuclease Drosha (canonical miRNA) or the spliceosome (intronic miRNA) [11], yielding a hairpin-like pre-miRNA (Figure 1). The pre-miRNAs are exported from the nucleus via the nucleocytoplasmic shuttle, Exportin-5, and subsequently processed by the cytosolic RNase III enzyme, Dicer, to produce a double-stranded miRNA duplex (miRNA-5p: 3p) ~22 nts in length [12]. One strand of the duplex, the guide strand, is preferentially incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) by an Argonaute (Ago) protein, directing the miRNA-loaded RISC to target mRNAs by interacting with sites of imperfect complementarities in 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) [1,13]. The non-incorporated strand of the pre-miRNA, referred to as the passenger strand, is released and degraded. Typically, the guide strand is the more conserved 5′ sequence (miR-5p) of the miRNA-5p:3p duplex and the generally lesser conserved 3′ sequence (miR-3p) serves as the passenger strand [4,14]. However, both strand species can co-accumulate and exert regulatory activity in various settings [14–16]. Most commonly, metazoan miRNAs fine-tune gene expression by mediating translational repression, mRNA destabilization, or a combination of these two mechanisms [17,18].

Figure 1.

Overview of miRNA biogenesis and function. Two predominant miRNA biogenesis pathways have been described, the canonical pathway and the intronic pathway. Canonical (pri-miRNA) and intronic (mRNA) miRNA are primarily transcribed by RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) and enzymatically processed by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex or spliceosome, respectively, to yield a hairpin precursor (pre-miRNA). pre-miRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by Exportin-5, where they are further processed by Dicer to yield dsRNA duplexes (miRNA-5p:3p) ~22nt in length. One strand of the miRNA-5p:3p duplex is loaded onto RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and guided to its mRNA via interactions with members of the Argonaute family (Ago1–4, Ago2) of proteins. miRNA-mediated gene silencing activity is primarily attributed to translational repression via mRNA destabilization or degradation.

In many cases, miRNAs are embedded within the gene expression network containing their mRNA targets. This connectivity allows miRNA responses that either exert restorative regulatory activity or enforce new gene expression programs through negative or positive feedback loops, respectively [19]. Significant genetic evidence indicates that miRNAs play key roles in mediating cellular stress responses to pathophysiological and physiological conditions, including oxidative stress [8,20,21], DNA damage and oncogenic stress [22], cardiac overload [23], insulin secretion [24] and the differentiation of activated B cells [25]. Among these are many conditions that impinge on the function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), leading to accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins, a cellular condition referred to as “ER stress”.

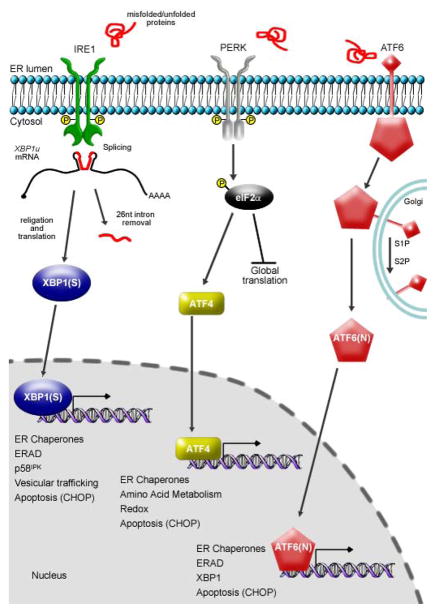

In response to the nature, intensity and duration of ER stress, cells launch the unfolded protein response (UPR), an intracellular signaling mechanism that triggers translational control and an extensive transcriptional response to balance client protein load with the folding capacity of the ER [26]. The mammalian UPR is comprised of three ER transmembrane sensors (Figure 2): protein kinase RNA-activated (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) [26]. Activated PERK phosphorylates the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), effectively down-regulating protein synthesis [27]. Paradoxically, this global diminution of protein synthesis allows for enhanced translation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) via a mechanism involving selection of alternative open reading frames in ATF4 mRNA [28–30]. As a transcriptional activator, ATF4 upregulates genes involved in a variety of cellular processes including amino acid metabolism, control of cellular redox and apoptosis [26,31]. Proteolytic processing of ATF6 yields an active transcription factor (ATF6(N)) [32,33]) that up-regulates expression of ER resident quality control proteins, including chaperones and ER-associated degradation (ERAD) components [34–36]. Upon activation of IRE1, its endoribonucleolytic activity catalyzes an unconventional cytosolic splicing of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA, resulting in a translational frameshift that generates XBP1(S), a pro-adaptive, basic leucine zipper transcription factor [37–39]. The endoribonuclease activity of IRE1, in a process termed regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD), has also been implicated in the degradation of mRNA and miRNA substrates [40–42]. If the adaptive mechanisms do not sufficiently recover ER homeostasis, the UPR can switch from a pro-adaptive to a pro-apoptotic role [43].

Figure 2.

Overview of UPR signaling. Three distinct signaling pathways, originating from ER transmembrane proteins, exist in the mammalian UPR: IRE1, PERK, and ATF6. Activation of IRE1 results in the unconventional cytosolic splicing of XBP1 mRNA and subsequent generation of XBP1(S), an inducer of UPR target genes that include ER chaperones, ERAD components and vesicular trafficking genes. Activated PERK phosphorylates eIF2α, leading to a global down-regulation of de novo protein synthesis and, paradoxically, increased expression of the transcription factor ATF4. ATF4 activates expression of genes encoding protein chaperones, ERAD components, enzymes that reduce oxidative stress and proteins that function in amino acid biosynthesis and transport. Recently, each UPR pathway has been linked to expression of the pro-apoptotic transcription factor CHOP. ATF6 is transported to the Golgi apparatus upon activation, where it is cleaved by the site 1 and site 2 proteases (S1P and S2P) to generate the cytosolic fragment, ATF6(N). ATF6(N) translocates to the nucleus as a functional transcription factor that upregulates expression of a variety of genes involved in ER quality control processes.

Though many stress responses that perturb the ER have been linked to miRNAs, the integration of miRNAs into specific UPR signaling pathways has only recently emerged. As modulators of gene expression, miRNAs are well-suited to finely adjust the cellular response to ER stress. Indeed, it is now apparent that ER stress-regulated miRNAs modulate translation of UPR effectors, synthesis of secretory pathway proteins and the fate of cells challenged with increased demands on the ER [44–46]. In this review, we fuse current understanding of the UPR with recent reports of miRNAs that regulate, and/or are regulated by, UPR-associated genes. Within this context, we discuss the emerging contribution of miRNAs to the bi-functional, pro-adaptive/pro-apoptotic roles of the UPR.

PRO-ADAPTIVE MICRORNAs

microRNAs and XBP1

XBP1(S) is a transcription factor that enhances a variety of ER and secretory pathway processes by up-regulating expression of genes involved in the entry of nascent polypeptides into the ER, protein folding and maturation within the ER, ERAD, and vesicular trafficking [47,48]. Several recent studies have reported relationships between miRNAs and XBP1 [44,46,49]. Our group identified a miRNA, miR-30c-2* (since designated miR-30c-2-3p), that targets a single site in the 3′-UTR of XBP1 mRNA, thereby influencing XBP1(S) expression levels and the survival of cells experiencing ER stress [46] (Table 1). Interestingly, miR-30c-2* is up-regulated during the UPR, concomitant with XBP1, suggesting that this miRNA might affect XBP1(S) expression levels as the UPR proceeds [46]. We found that up-regulation of miR-30c-2* is dependent on the protein kinase PERK, another key signaling component of the UPR. This mechanism involves the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and its interaction with a NF-κB enhancer motif upstream of the miR-30c-2* genes [46]. In the UPR, NF-κB is activated downstream of PERK [50,51]. Importantly, these results identified a novel miRNA-mediated mechanism for “cross-talk” between the PERK and IRE/XBP1 signaling branches of the UPR.

Table 1.

Differential miRNA activity contributes to pro-adaptive and pro-apoptotic UPR signaling. Summary table of miRNAs that have been linked to UPR activation and function.

| microRNA | Regulation | Gene Target(s) | Contribution to the UPR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-346 | XBP1(S) | TAP1 | ADAPTIVE - reduces TAP1 expression, potentially decreasing MHC class I- associated antigen presentation | 44 |

| miR-708 | CHOP | Rhodopsin | ADAPTIVE - reduces ER protein folding demand | 45 |

| miR-30c-2-3p | NF-κB (downstream of PERK) | XBP1 | ADAPTIVE - governs XBP1 expression as the UPR proceeds | 46 |

| miR-214 | NF-κB (correlation) | XBP1 | ADAPTIVE - governs XBP1 expression until the UPR is activated | 49 |

| miR-221/222 | CHOP (correlation) | p27Kip1 | APOPTOTIC - contributes to p27 Kip1 and MEK/ERK-mediated G1 phase arrest | 78 |

| miR-455 | ATF6 | Calreticulin (correlation) | ADAPTIVE - regulates calreticulin levels | 59 |

| miR-663 | ER stress-inducible | ATF4 (correlation) | ADAPTIVE - indirectly reduces ATF4 targets, VEGF and TRIB | 63 |

| miRs -17, -34a, -96, -125b | IRE1-mediated degradation | Caspase-2 | ADAPTIVE - miRs inhibit Caspase-2 translation, until IRE1 degrades the miRs, leading to apoptosis initiation | 42 |

| miR-204 | ER stress-inducible | not identified | APOPTOTIC - general inhibitory affect on UPR induction | 74 |

| miR-122 | ER stress-inducible | ER stress proteins (correlation) | APOPTOTIC - miR-122-PSMD10-UPR mediated UPR gene regulation | 76 |

| miR-23a~27a~24-2 | ER stress-inducible | not identified | APOPTOTIC - increases ROS production; preferentially activate PERK and IRE1 | 68, 69, 71 |

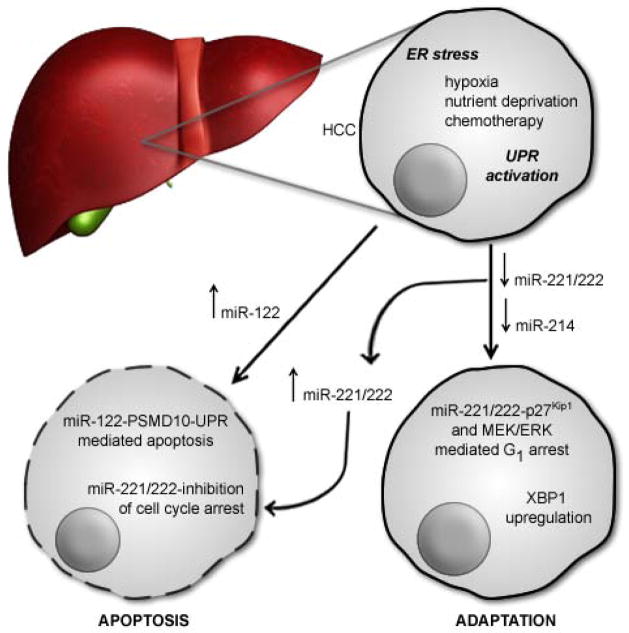

Another miRNA, miR-214, was recently reported as a negative regulator of XBP1 expression in hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) [49] (Table 1). UPR activation is associated with poor clinical outcome, increasing tumor grade, and resistance to ER stress-induced apoptosis in HCC [52,53]. Though numerous reports have linked miRNA dysregulation to liver cancers, the role of miRNAs during the UPR in these solid tumors remains in the early stages of discovery. In HCC, miR-214 expression is down-regulated in response to ER stress, suggesting that miR-214 represses XBP1 expression until the UPR is activated (Figure 3). NF-κB activation correlated with a negative regulatory effect on expression of the miR-199a/214 gene cluster [49]. However, a direct binding site through which NF-κB mediates this effect was not demonstrated, raising the possibility of an indirect regulatory mechanism(s).

Figure 3.

UPR-associated miRNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Hypoxia, nutrient deprivation and chemical stress are ER stressors characteristic of the HCC cellular environment. In HCC, miR-214, miR-221/222, and miR-122 have been linked to UPR-mediated adaptation. miR-214 is expressed in HCC until UPR activation suppresses its expression. Since miR-214 targets pro-adaptive XBP1, suppression of miR-214 allows expression of XBP1 and cellular adaptation to stress. In non-cancerous liver tissue, miR-221/222 is up-regulated during a persistent UPR, where it suppresses its target p27Kip1, and allows the stressed cell to proceed to apoptosis. In the pathology of HCC, dysregulation of miR-221/222 during the UPR relieves suppression of p27Kip1 and allows G1 phase arrest, thereby aiding in cellular adaptation, HCC viability, and decreased susceptibility to treatment. miR-122 is up-regulated during the UPR and aids in ER-mitochondria crosstalk-mediated apoptosis via a novel miR-122-PSMD10-UPR apoptosis pathway.

Bartoszewski and colleagues [44] recently identified miR-346 as being subject to XBP1(S) transcriptional control (Table 1). miR-346 is up-regulated in response to ER stress in an XBP1-dependent fashion, and enforced expression of XBP1(S) is sufficient to induce miR-346. In addition, the ER antigen peptide transporter (TAP1) mRNA is a direct target of miR-346 [44]. TAP1 is necessary for proper assembly of MHC class I-peptide complexes [54], a process that is down-regulated during ER stress [55–57]. Therefore, it is intriguing to speculate that miR-346, downstream of XBP1(S), targets TAP1 and dampens MHC class I biogenesis under conditions that perturb the ER and activate the UPR [44]. Further studies will be necessary to test this model during pathological conditions, such as viral infection, that involve MHC class I-antigen presentation and are associated with UPR induction.

microRNAs and Activating Transcription Factors

ATF6 is an activating transcription factor that senses ER stress and induces numerous genes encoding proteins which restore ER homeostasis [34–36]. In response to ischemia in the heart, ATF6 aids in decreasing infarct size, limiting apoptosis, and improving functional recovery upon reperfusion [58]. A recent study reported that part of this ATF6 pro-adaptive response can be attributed to a subset of ATF6-inducible miRNAs [59]. Specifically, in cardiomyocytes and in the heart of tamoxifen-inducible-ATF6 (ATF6-MER) transgenic mice, activated ATF6 altered the levels of 13 miRNAs, 8 of which were down-regulated and 5 were up-regulated [59]. The study further showed that ATF6-inducible miR-455 may regulate calreticulin levels (Table 1). Calreticulin, an ER resident Ca2+-binding molecular chaperone, contributes to the folding of nascent polypeptides [60]. A strong correlation was shown between ATF6 down-regulation of miR-455 and subsequent augmentation of calreticulin expression. The authors proposed a new facet to the protective effect of ATF6 in the ischemic heart, whereby ATF6 down-regulates miR-455, leading to up-regulation of the cardio-protective gene, calreticulin [59]. Seed-sequence validation and direct targeting studies of miR-455, as well as the other ATF6-dependent miRNAs identified in this study, will certainly be of great interest to this field.

Recent reports have also implicated a pro-adaptive role for miRNAs via the ATF4 arm of the UPR [45,61]. ATF4, a downstream effector of PERK (Figure 2), activates a variety of genes including the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP), a transcription factor associated with apoptosis [31,62]. Behrman and colleagues [45] identified miR-708, an intronic miRNA encoded within Odz4, as a transcriptional target of CHOP. Odz4 and miR-708 are co-expressed in the brain and eyes of mice, suggesting common physiological function(s) in these tissues [45] (Table 1). Indeed, rhodopsin, a transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor expressed in the retina, is subject to regulation by miR-708 [45]. Since the folding and transport of rhodopsin relies on ER function, it was proposed that induction of miR-708 in the UPR alleviates protein folding demand by reducing the flow of nascent rhodopsin into the stressed ER [45]. Interestingly, this study implies a miRNA-inclusive, pro-adaptive role for CHOP early in the UPR.

ATF4 has also been linked to miR-663. A study by Afonyushkin, et al. [61] revealed the induction of miR-663 in aortic and venous endothelial cells (EC) in response to oxidized palmitoyl-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylcholine (OxPAPC), which has been shown to cause ER stress and induce the UPR [63]. Inhibition of miR-663 during OxPAPC-induced ER stress correlates with attenuated expression of ATF4 expression and the ATF4 target genes, VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and TRIB (testis-specific ribbon protein) [61] (Table 1). Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism by which miR-663 suppresses ATF4 expression and the role this might play in controlling expression of its downstream targets.

These reports provide evidence for the interplay between miRNAs and the pro-adaptive activity of UPR-associated transcription factors. Specifically, the transcription factor XBP1(S) appears to be embedded in the genetic network of miRNA expression [44] and regulation [46,49]. Biosynthesis of the pro-adaptive XBP1(S) involves a unique cytosolic splicing event mediated by the RNase activity of the ER stress sensor and UPR component, IRE1. IRE1 also promotes apoptosis through incompletely understood mechanisms. However, Upton and colleagues [42] recently reported selective cleavage of miRNAs by IRE1. During unmitigated ER stress, the protease CASPASE-2 (CASP2) is activated, triggering the mitochondrial BAX/BAK-dependent apoptosis pathway [64]. A subset of miRNAs (miR-17, -34a, -96, 125b) that repress translation of CASP2 mRNA were identified as targets of IRE1 RNase activity [42]. Activation of IRE1 resulted in a decrease in the abundance of these mature miRNAs and their pre-miRNA precursor, but not of the corresponding nucleolar pri-miRNA molecule. Furthermore, each miRNA can regulate CASP2 expression by interacting with the target sites in the CASP2 mRNA 3′UTR, and IRE1 activation correlates with increases in CASP2 protein production, without altering CASP2 gene transcription [42]. Finally, IRE1-mediated cleavage of miR-17 maps to a position that is distinct from DICER sites, but possesses similarities to IRE1 cleavage recognition sequences in XBP1 mRNA [42]. This novel discovery provides the first evidence that IRE1-mediated RNase activity selectively targets pro-adaptive miRNAs to initiate CASP2-dependent, mitochondrial-induced cellular apoptosis. Interestingly, in pancreatic β cells experiencing ER stress, IRE1 reduces miR-17, thereby contributing to the stabilization of the mRNA encoding the pro-oxidant thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) [41]. In turn, TXNIP activates the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, thereby promoting inflammation and programmed cell death [41,65]. Therefore, in addition to regulating expression of the pro-adaptive factor XBP1(S), the IRE1 endoribonuclease de-represses cell death-promoting mechanisms by cleaving miR-17.

PRO-APOPTOTIC MICRORNAs

Apoptosis is a highly regulated programmed cell death event characterized by cytoskeletal disruption, cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, chromatin condensation, and DNA fragmentation [64]. The involvement of miRNAs in apoptosis has been predominantly studied in the context of tumorigenesis in various cancer types, where certain miRNAs (e.g. miR-29b, miR-15-16, let-7/miR-98 and miR-17-92) influence apoptotic signaling cascades [66]. In a prolonged UPR, where ER stress remains unmitigated, ER stress-induced apoptosis is initiated [43]. Though the nature of the switch from pro-adaptive to pro-apoptotic signaling in the UPR is not fully understood, it is known that UPR components can activate both mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent apoptosis [67].

Several studies have linked a cluster of miRNAs, miR-23a~27a~24-2, to various cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, proliferation, differentiation and hematopoiesis [68]. All three mature miRNAs of this cluster are derived from a single transcript, but can be differentially expressed in various settings. Chhabra, et al. [69] initially observed that upregulation of the miR-23a~27a~24-2 cluster induces apoptosis by both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways via c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Table 1). JNK, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family of signaling molecules, is responsive to stress stimuli and induces expression of genes encoding mediators of host defense, including apoptotic factors [70]. When the UPR and ERAD fail to sufficiently alleviate ER stress, the UPR is involved in a signaling cascade, occurring via PERK/eIF2α-induced CHOP and/or IRE1-mediated activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1(ASK1)/JNK, which leads to apoptosis [43,67]. Interestingly, miR-23a~27a~24-2 upregulation alone is sufficient to cause ER stress and induce expression of genes associated with PERK and IRE1 activation during the UPR [71]. Inhibition of endogenous miR-23a~27a~24-2 correlated with increased expression of several pro-adaptive genes. However, upregulation of miR-23a~27a~24-2 also led to significant release of ER Ca2+ stores into the cytoplasm and a concomitant increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability [71]. Therefore, Chhabra and colleagues [71] proposed that upregulation of miR-23a~27a~24-2 increases ROS production which perturbs the ER environment, leading to preferential activation of the PERK and IRE1/ASK1/JNK apoptotic signaling cascades. This intriguing model involving miRNAs, the UPR, and ER-mitochondria crosstalk, warrants further investigation. Specifically, a more thorough analysis of UPR pathways activated in response to the inhibition of endogenous miR-23a~27a~24-2 may provide insight into the relationship between this miRNA cluster and ER stress-sensing molecules. Equally important will be further studies of the relative accumulation and individual role(s) of each miRNA expressed in the cluster.

Another miRNA, miR-204, was recently implicated in ER stress-responsive gene modulation and apoptosis susceptibility in human trabecular meshwork (HTM) cells. Senescence of HTM cells has been proposed to play a role in the functional alterations of this tissue in primary open angle glaucoma, a chronic condition involving optic nerve damage [72]. Li, et al. [73] reported that senescence of HTM cells is associated with significant changes in expression of several miRNAs, including miR-204, which might contribute to phenotypic alterations characteristic of senescent cells. Interestingly, over-expression of miR-204 increases apoptosis in response to oxidative stress and pharmacologic ER stress [74] (Table 1). Over-expressing miR-204 also attenuates induction of ER stress responsive genes including GRP94, GRP78/BiP, and CHOP. Direct targets of miR-204 have been identified, but UPR-associated genes are not among those validated experimentally [74]. Though it appears miR-204 may have a general inhibitory affect on UPR induction, additional gene target verification is necessary to fully understand the direct/indirect role(s) of miR-204 during ER stress. Presently, it seems that miR-204 is potentially involved in multiple functions in HTM cells including apoptosis, accumulation of damaged proteins and the ER stress response.

The complexity of miRNA regulation during the UPR is particularly evident in HCC (Figure 3). In addition to the potential role of miR-214 in the regulation of XBP1 expression in HCC (as discussed above), miR-122 and miR-221/222 have been linked to apoptosis during the UPR in this type of cancer (Table 1). In fact, miR-122 is the most abundant miRNA in the liver and can influence the sensitivity of HCC cells to doxorubicin through both p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptotic pathways [75]. Recently, Yang and colleagues [76] provided additional insight into potential mechanism by which miR-122 may influence cell fate. In vitro inhibition of miR-122 in human hepatoma cells leads to increased expression of ER stress-associated proteins such as calreticulin and ER protein 29 (ERp29). In addition, inhibition of miR-122 leads to up-regulation of CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4), a direct target of miR-122, and enhances stability of the 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 10 (PSMD10, also known as Gankyrin and p28GANK) [76]. PSMD10, a CDK4-interacting protein, is expressed at high levels in HCC and has been implicated in UPR enhancement [52], tumor growth progression and inhibition of apoptosis [77]. Therefore, Yang et al. [76] suggested a pro-apoptotic role for miR-122, whereby expression of select UPR-associated genes is modulated via a novel miR-122-PSMD10-UPR pathway (Figure 3).

In other studies of HCC cells, Dai and colleagues [78] reported that miR-221/222 is suppressed during ER stress by a mechanism involving CHOP. Suppression of these miRNAs in HCC cells allowed accumulation of the p27Kip1 protein, a direct target for miR-221/222 (Figure 3). p27Kip1, a CDK inhibitor that binds directly to G1 cyclin-CDK complexes, controls cell proliferation by promoting G1 arrest [79]. Also, miR-221/222 suppression correlated with increased G1 phase arrest mediated by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-MAPK (MEK/ERK) pathway [78]. Taken together, these data suggest that UPR-induced down-regulation of miR-221/222 allows enhancement of both p27Kip1- and MEK/ERK-mediated G1 phase arrest, thereby promoting ER stress adaptation and survival of HCC cells [78]. Since miR-221/222 levels are typically lower in non-cancerous liver tissues, it follows that miR-221/222 normally promotes apoptosis triggered by ER stress [78]. However, in the context of HCC, UPR-mediated suppression of miR-221/222 contributes to the pathology by promoting cell cycle arrest (Figure 3). Thus, the dysregulation of UPR associated miRNAs can affect both pro-adaptive/pro-apoptotic cellular signaling mechanisms in these cancer cells.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

While many cell types, such as specialized secretory cells, possess a remarkable ability to alleviate ER stress through UPR activation, pathological conditions can overwhelm the maintenance of ER homeostasis. Elucidation of the molecular switches that determine when ER stress is irremediable is of great interest. The emergence of miRNAs that are embedded in the UPR genetic network has profound implications for understanding their roles in gene regulation in vivo. As all three UPR sensors (Figure 2), IRE1, PERK and ATF6, have pro-adaptive outputs that can switch into apoptotic signaling, it is interesting to consider a potential role for select miRNAs as ‘timers’ that might trigger this critical cell fate switch. For example, under excessive or chronic ER stress conditions an expression network of miRNA that regulate pro-adaptive/pro-apoptotic genes [46,49,76] might influence the decision of life versus death for the affected cells. In addition, the finding that IRE1-mediated miRNA degradation leads to activation of the initiator caspase, C2 [42], directly links ER signaling to mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Moving forward, it will also be of interest to determine if one or more of the three UPR sensors might be targeted by select miRNAs. Importantly, advances in understanding how miRNAs are intertwined in UPR-mediated adaptive and apoptotic signaling will hopefully reveal novel therapeutic potential for diseases associated with ER dysfunction and/or the UPR.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the US National Institutes of Health for grant support (GM061970).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Andrew E. Byrd, Email: eab303@jaguar1.usouthal.edu.

Joseph W. Brewer, Email: jbrewer@southalabama.edu.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambros V, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Burge CB, Carrington JC, et al. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA. 2003;9:277–299. doi: 10.1261/rna.2183803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294:853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung AKL, Sharp PA. Function and localization of microRNAs in mammalian cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:29–38. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung AKL, Sharp PA. MicroRNA functions in stress responses. Mol Cell. 2010;40:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YK, Kim VN. Processing of intronic microRNAs. EMBO J. 2007;26:775–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JS, Phillips MD, Betel D, Mu P, Ventura A, et al. Widespread regulatory activity of vertebrate microRNA* species. RNA. 2011;17:312–326. doi: 10.1261/rna.2537911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamura K, Phillips MD, Tyler DM, Duan H, Chou YT, et al. The regulatory activity of microRNA* species has substantial influence on microRNA and 3′ UTR evolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:354–363. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ro S, Park C, Young D, Sanders KM, Yan W. Tissue-dependent paired expression of miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5944–5953. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shalgi R, Lieber D, Oren M, Pilpel Y. Global and local architecture of the mammalian microRNA-transcription factor regulatory network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulshreshtha R, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Garzon R, Alder H, et al. A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1859–1867. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsit CJ, Eddy K, Kelsey KT. MicroRNA responses to cellular stress. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10843–10848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayed D, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:827–887. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill J, et al. Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. 2007;316:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.1139089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, et al. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vigorito E, Perks KL, Abreu-Goodger C, Bunting S, Xiang Z, et al. MicroRNA-155 regulates the generation of immunoglobulin class-switched plasma cells. Immunity. 2007;27:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream orfs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wek RC, Cavener DR. Translational control and the unfolded protein response. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2357–2371. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Dave UP, et al. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J, Rutkowski DT, Dubois M, Swathirajan J, Saunders T, et al. ATF6α optimizes long-term endoplasmic reticulum function to protect cells from chronic stress. Dev Cell. 2007;13:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto K, Sato T, Matsui T, Sato M, Okada T, et al. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6α and XBP1. Dev Cell. 2007;13:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adachi Y, Yamamoto K, Okada T, Yoshida H, Harada A, et al. ATF6 is a transcription factor specializing in the regulation of quality control proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Struct Funct. 2008;33:75–89. doi: 10.1247/csf.07044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen X, Ellis R, Lee K, Liu CY, Yang K, et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell. 2001;107:893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, et al. Regulated IRE1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lerner AG, Upton JP, Praveen PVK, Ghosh R, Nakagawa Y, et al. IRE1α induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012;16:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upton JP, Wang L, Han D, Wang ES, Huskey NE, et al. IRE1α cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic caspase-2. Science. 2012;338:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1226191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartoszewski R, Brewer JW, Rab A, Crossman DK, Bartoszewska S, et al. The unfolded protein response (UPR)-activated transcription factor X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) induces microRNA-346 expression that targets the human antigen peptide transporter 1 (TAP1) mRNA and governs immune regulatory genes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41862–41870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Behrman S, Acosta-Alvear D, Walter P. A CHOP-regulated microRNA controls rhodopsin expression. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:919–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrd AE, Aragon IV, Brewer JW. MicroRNA-30c-2* limits expression of proadaptive factor XBP1 in the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:689–698. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duan Q, Wang X, Gong W, Ni L, Chen C, et al. ER stress negatively modulates the expression of the mir-199a/214 cluster to regulate tumor survival and progression in human hepatocellular cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;2012(7):e31518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng J, Lu PD, Zhang Y, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, et al. Translational repression mediates activation of nuclear factor kappa b by phosphorylated translation initiation factor 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10161–10168. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10161-10168.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang HY, Wek SA, McGrath BC, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, et al. Phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is required for activation of NF-kappa b in response to diverse cellular stresses. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5651–5663. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5651-5663.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dai RY, Chen Y, Fu J, Dong LW, Ren YB, et al. p28Gank inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death via enhancement of the endoplasmic reticulum adaptive capacity. Cell Res. 2009;19:1243–1257. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shuda M, Kondoh N, Imazeki N, Tanaka K, Okada T, et al. Activation of the ATF6, XBP1 and GRP78 genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma: a possible involvement of the ER stress pathway in hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol. 2003;38:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lankat-Buttgereit B, Tampe R. The transporter associated with antigen processing: function and implications in human diseases. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:187–204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Almeida SF, Fleming JV, Azevedo JE, Carmo-Fonseca M, de Sousa M. Stimulation of an unfolded protein response impairs MHC class I expression. J Immunol. 2007;178:3612–3619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Granados DP, Tanguay PL, Hardy MP, Caron E, de Verteuil D, et al. ER stress affects processing of MHC class I-associated peptides. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ulianich L, Terrazzano G, Annunziatella M, Ruggiero G, Beguinot F, et al. ER stress impairs MHC class I surface expression and increases susceptibility of thyroid cells to NK-mediated cytotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martindale JJ, Fernandez R, Thuerauf D, Whittaker R, Gude N, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress gene induction and protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury in the hearts of transgenic mice with a tamoxifen-regulated form of ATF6. Circ Res. 2006;98:1186–1193. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000220643.65941.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belmont PJ, Chen WJ, Thuerauf DJ, Glembotski CC. Regulation of microRNA expression in the heart by the ATF6 branch of the ER stress response. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1176–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Michalak M, Groenendyk J, Szabo E, Gold LI, Opas M. Calreticulin, a multiprocess calcium-buffering chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J. 2009;417:651–666. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Afonyushkin T, Oskolkova OV, Bochkov VN. Permissive role of mir-663 in induction of VEGF and activation of the ATF4 branch of unfolded protein response in endothelial cells by oxidized phospholipids. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, Batchvarova N, Lightfoot RT, et al. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gargalovic PS, Imura M, Zhang B, Gharavi NM, Clark MJ, et al. Identification of inflammatory gene modules based on variations of human endothelial cell responses to oxidized lipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12741–12746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605457103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oslowski CM, Hara T, O’Sullivan-Murphy B, Kanekura K, Lu S, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates ER stress-induced β cell death through initiation of the inflammasome. Cell Metab. 2012;16:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Y, Lee CGL. MicroRNA and cancer--focus on apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jager R, Bertrand MJ, Gorman AM, Vandenabeele P, Samali A. The unfolded protein response at the crossroads of cellular life and death during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biol Cell. 2012;104:259–270. doi: 10.1111/boc.201100055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chhabra R, Dubey R, Saini N. Cooperative and individualistic functions of the microRNAs in the mir-23a~27a~24-2 cluster and its implication in human diseases. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:232. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chhabra R, Adlakha YK, Hariharan M, Scaria V, Saini N. Upregulation of mir-23a-27a-24-2 cluster induces caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis in human embryonic kidney cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chhabra R, Dubey R, Saini N. Gene expression profiling indicate role of ER stress in mir-23a~27a~24-2 cluster induced apoptosis in HEK293T cells. RNA Biol. 2011;8:648–664. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.15583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liton PB, Challa P, Stinnett S, Luna C, Epstein DL, et al. Cellular senescence in the glaucomatous outflow pathway. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:745–748. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li G, Luna C, Qiu J, Epstein DL, Gonzalez P. Alterations in microRNA expression in stress-induced cellular senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:731–741. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li G, Luna C, Qiu J, Epstein DL, Gonzalez P. Role of mir-204 in the regulation of apoptosis, endoplasmic reticulum stress response, and inflammation in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2999–3007. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fornari F, Gramantieri L, Giovannini C, Veronese A, Ferracin M, et al. Mir-122/cyclin G1 interaction modulates p53 activity and affects doxorubicin sensitivity of human hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5761–5767. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang F, Zhang L, Wang F, Wang Y, Huo XS, et al. Modulation of the unfolded protein response is the core of microRNA-122-involved sensitivity to chemotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2011;13:590–600. doi: 10.1593/neo.11422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Higashitsuji H, Itoh K, Nagao T, Dawson S, Nonoguchi K, et al. Reduced stability of retinoblastoma protein by gankyrin, an oncogenic ankyrin-repeat protein overexpressed in hepatomas. Nat Med. 2000;6:96–99. doi: 10.1038/71600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dai R, Li J, Liu Y, Yan D, Chen S, et al. Mir-221/222 suppression protects against endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis via p27(Kip1)- and MEK/ERK-mediated cell cycle regulation. Biol Chem. 2010;391:791–801. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sgambato A, Cittadini A, Faraglia B, Weinstein IB. Multiple functions of p27(Kip1) and its alterations in tumor cells: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:18–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<18::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]