Abstract

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is the nitric oxide synthase isoform responsible for maintaining systemic blood pressure, vascular remodelling and angiogenesis1-4. eNOS is phosphorylated in response to various forms of cellular stimulation5-7, but the role of phosphorylation in the regulation of nitric oxide (NO) production and the kinase(s) responsible are not known. Here we show that the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt (protein kinase B) can directly phosphorylate eNOS on serine 1179 and activate the enzyme, leading to NO production, whereas mutant eNOS (S1179A) is resistant to phosphorylation and activation by Akt. Moreover, using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer, activated Akt increases basal NO release from endothelial cells, and activation-deficient Akt attenuates NO production stimulated by vascular endothelial growth factor. Thus, eNOS is a newly described Akt substrate linking signal transduction by Akt to the release of the gaseous second messenger NO.

The Akt proto-oncogene is an important regulator of various cellular processes including glucose metabolism and cell survival8,9. Activation of receptor tyrosine kinases and G-protein-coupled receptors, and stimulation of cells by mechanical forces, can lead to the phosphorylation and activation of Akt10-12. Akt can then phosphorylate substrates such as glycogen synthase kinase-3, Bad and caspase-9, resulting in protein inactivation, or 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase, resulting in protein activation10,13. The relationships between activation of Akt, its downstream effectors and the production of soluble second messengers are not well understood.

eNOS is the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoform that produces endothelium-derived NO. Treatment of endothelial cells with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or insulin stimulates the production of NO by a phosphatidylinositol-3-OH-kinase (PI(3)K)-dependent mechanism14,15. Wortmannin and LY294002, two structurally dissimilar inhibitors of PI(3)K, partially block NO release. VEGF also stimulates the Ras pathway; inhibition of Ras signalling blocks extracellular-signal-related-kinase (ERK)-1/2 activation, but not VEGF-stimulated NO production, indicating that there may be a link between growth factor signalling through PI(3)K and eNOS16.

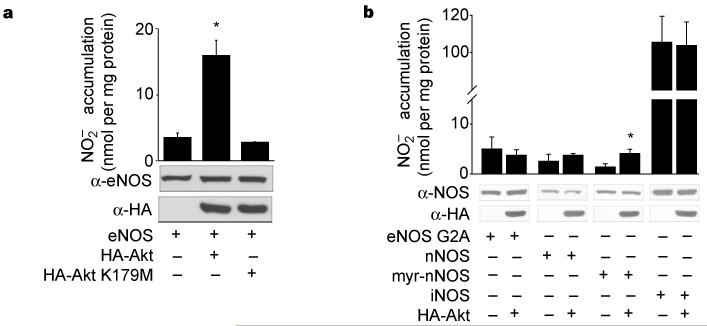

To investigate whether Akt, a downstream effector of PI(3)K, could directly influence the production of NO, COS-7 cells (which do not express NOS) were co-transfected with eNOS and wild-type Akt (HA–Akt) or kinase-inactive Akt (HA–Akt K179M), and the accumulation of nitrite () was measured by NO-specific chemiluminescence. Transfection of eNOS results in increased accumulation, which is markedly enhanced by co-transfection of wild-type Akt, but not the kinase-inactive variant (Fig. 1a). Identical results were obtained using cyclic GMP (cGMP) as a bioassay for biologically active NO. Transfection of a constitutively active form of Akt (myr-Akt) increases cGMP accumulation (assayed in COS cells) from 5.5 ± 0.8 to 11.6 ± 0.9 pmol cGMP per mg protein (in cells transfected with eNOS alone or eNOS with myr-Akt, respectively) whereas the kinase-inactive Akt did not influence cGMP accumulation (5.8 ± 0.8 pmol cGMP, n = 4 experiments). Under these experimental conditions, Akt was catalytically active, as determined by western blotting with a phospho-Akt-specific antibody (which recognizes serine 473; data not shown) and Akt activity assays (see Fig. 2a). Equal levels of eNOS and Akt were expressed in COS cell lysates (Fig. 1), indicating that Akt modulates eNOS, thereby increasing NO production under basal conditions.

Figure 1.

Wild-type Akt, but not kinase-inactive Akt, increases NO release from cells expressing membrane-associated eNOS. a, COS cells were transfected with plasmids for eNOS, with or without Akt or kinase-inactive Akt (K179M). The production of NO (assayed as ) was determined by chemiluminescence. b, COS cells were transfected with various NOS plasmids as above. In both a and b, values for production were subtracted from levels obtained from cells transfected with the β-galactosidase cDNA only. The insets show the expression of proteins in total cell lysates. Data were mean ± s.e.m., n = 3-7 experiments; asterisk denotes P < 0.05.

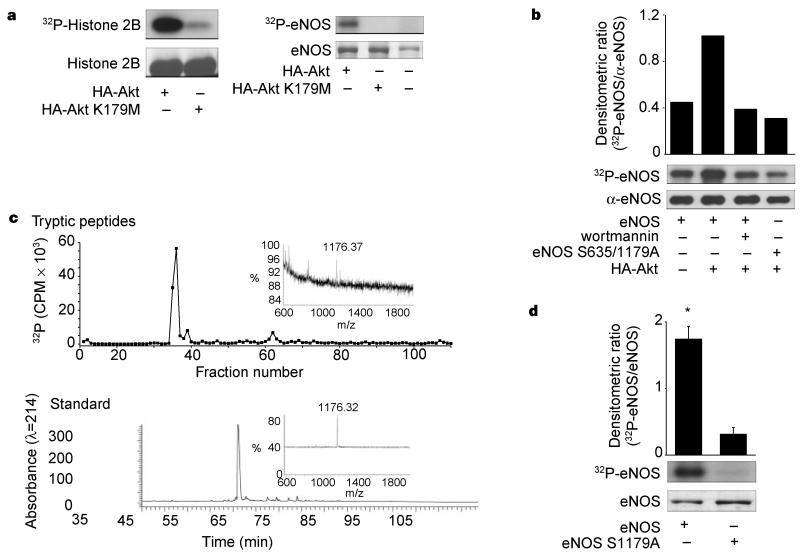

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of eNOS by active Akt in vitro and in vivo. a, COS cells were transfected with HA-Akt or HA-Akt(K179M) and lysates were immunoprecipitated and placed into an in vitro kinase reaction with histone 2B (25 μg) or recombinant eNOS (3 μg) as substrates. Top panel: incorporation of 32P into the substrates; Bottom panel: amount of substrate by Coomassie staining of the gel. b, 32P-labelled wild-type or double-serine mutant of eNOS (eNOS S635/1179A) was affinity purified from transfected COS cells and subjected to autoradiography (upper panel) or western blotting (lower panel). The histogram shows the relative amount of labelled protein to the amount of immunoreactive eNOS in the gel. c, Labelled eNOS was digested with trypsin and peptides separated by RP-HPLC. The upper panel shows a predominant labelled tryptic peptide that comigrates with the unlabelled synthetic phosphopeptide standard (bottom panel). Insets: linear mode MS of labelled peptide (top) and phosphopeptide standard showing identical mass ions (bottom). d, Recombinant wild-type eNOS or eNOS S1179A were purified and equal amounts (2.4 μg) placed into an in vitro kinase reaction with recombinant Akt (see Methods). Top panel: the incorporation of 32P into eNOS; bottom panel; amount of substrate by Coomassie staining of the gel. Histogram (n = 3) reflects the relative amount of labelled eNOS to the mass of eNOS (Coomassie) in the in vitro kinase reaction.

eNOS is a dually acylated peripheral membrane protein that targets into the Golgi region and plasma membrane of endothelial cells17-19; compartmentalization is required for efficient production of NO in response to agonist challenge20-22. To test whether eNOS activation by Akt requires membrane compartmentalization, we cotransfected COS-7 cells with complementary DNAs for Akt and a myristoylation, palmitoylation-defective mutant of eNOS (G2A eNOS); we then quantified the release of NO. Akt did not activate the non-acylated form of eNOS (Fig. 1b), indicating that compartmentalization of both proteins to the membrane is required for their functional interaction10. Next, we tested whether Akt could activate two structurally similar but distinct soluble NOS isoforms, neuronal NOS and inducible NOS (nNOS and iNOS, respectively). Cotransfection of Akt with nNOS and iNOS did not result in a further increase in NO release, demonstrating the specificity of Akt for eNOS. However, the addition of an N-myristoylation site to nNOS, to enhance its interactions with biological membranes, results in Akt stimulation of nNOS in a manner analogous to that seen with eNOS, indicating that both isoforms may be susceptible to activation by Akt when anchored to the membrane.

The above data indicate that Akt, perhaps by phosphorylation of eNOS, can modulate NO release from intact cells. Indeed, two putative Akt phosphorylation motifs (RXRXXS/T) are present in eNOS (serines 635 and 1179 in bovine eNOS; serines 633 and 1177 in human eNOS) and one motif is present in nNOS (serines 1412 in rat and 1415 in human nNOS), with no obvious motifs found in iNOS. To test whether eNOS is a potential substrate for Akt phosphorylation in vitro, we transfected COS cells with HA–Akt or HA–Akt (K179M), and assessed kinase activity using recombinant eNOS as a substrate. The active kinase phosphorylates histone 2B and eNOS (Fig. 2a; 69.3 ± 2.9 and 115.4 ± 3.8 pmol of ATP per nmol substrate, respectively; n = 3), whereas the inactive Akt did not significantly increase histone or eNOS phosphorylation. To investigate whether the putative Akt phosphorylation sites in eNOS were responsible for the incorporation of 32P, the two serines were mutated to alanine residues and the ability of Akt to stimulate wildtype and mutant eNOS phosphorylation was examined in intact COS cells. We labelled transfected cells with 32P-orthophosphate and partially purified eNOS by ADP-sepharose affinity chromatography, and quantified the phosphorylation state and protein levels. Co-expression of Akt results in a twofold enhancement in the phosphorylation of eNOS relative to non-stimulated cells (Fig. 2b). Pretreatment of eNOS/Akt-transfected cells with wortmannin abolished the Akt-induced increase in phosphorylation. Moreover, mutation of serines 635 and 1179 to alanine residues abolished Aktdependent phosphorylation of eNOS, indicating that these residues could serve as potential phosphorylation sites in intact cells. To directly identify the residues phosphorylated by Akt, we incubated wild-type eNOS with immunopurified Akt and determined the sites of phosphorylation by high-performance liquid chromatography followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDi-MS). The primary 32P-labelled tryptic phos-phopeptide co-elutes with a synthetic phosphopeptide (amino acids 1177–1185 with phosphoserine at position 1179) and has the identical mass ion as determined by linear mode MS (Fig. 2c). Using reflectron mode MALDi-MS monitoring, both the labelled tryptic peptide and the standard phosphopeptide demonstrated a loss of H3PO4, indicating that the tryptic peptide was phosphorylated. In addition, mutation of Ser 1179 to alanine markedly reduces Akt-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS compared with the wild-type protein (Fig. 2d). Identical results were obtained using peptides (amino acids 1174–1194) derived from wild-type or eNOS S1179A as substrates for recombinant Akt (the wild-type peptide incorporated 24.6 ± 3.7 nmol phosphate per mg compared to the alanine mutant peptide, which incorporated 0.22 ± 0.02 nmol phosphate per mg; n = 5). These data show that eNOS is a substrate for Akt and that the primary site of phosphorylation is serine 1179.

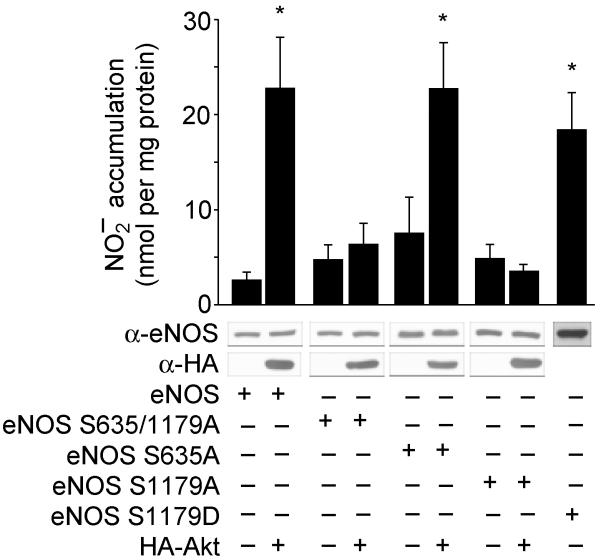

Next we examined the functional significance of the putative Akt phosphorylation site at Ser 635 and the identified site at Ser 1179. Transfection of COS cells with the double mutant eNOS S635/1179A abolishes Akt-dependent NO release. Mutation of Ser 635 to alanine did not attenuate NO release, whereas eNOS S1179A abolishes Akt-dependent activation of eNOS (Fig. 3). These results indicate that Ser 1179 is functionally important for NO release. Mutation of Ser 1179 into aspartic acid (eNOS S1179D), to substitute for the negative charge afforded by the addition of phosphate, partially mimics the activation state induced by Akt. All site-directed mutants were amply expressed (see inset western blots) and retained NOS catalytic activity in cell lysates (in COS cells transfected with eNOS only, NOS activity was 85.3 ± 27.0, 71.9 ± 2.9, 80.8 ± 23.2 and 131.8 ± 36.7 pmol L-citrulline generated per mg protein from lysates of COS cells expressing wild-type, S1179A, S635/1179A and S1179D eNOS, respectively; n = 3 experiments).

Figure 3.

Evidence that Ser 1179 is functionally important for Akt-stimulated NO release. COS cells were transfected with plasmids for wild-type eNOS or eNOS mutants, in the absence or presence of Akt, and the expression of the proteins and production of NO (assayed as ) were determined. Constructs with the S1179A mutation were not activated by Akt; the S1179D mutation resulted in a gain of function. Data are mean ± s.e.m. of 4-7 experiments; asterisks represent significant differences (P < 0.05).

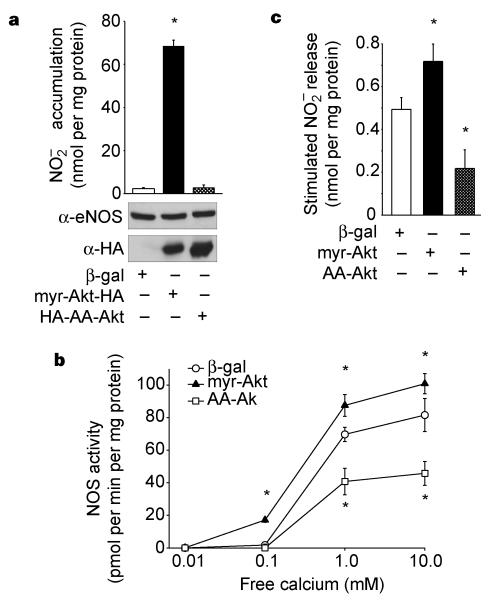

To test whether Akt mediates NO release from endothelial cells, we infected bovine lung microvascular endothelial cells (BLMVEC) with adenoviruses expressing activated Akt (myr-Akt), activation-deficient Akt (AA-Akt) or β-galactosidase (as a control), and measured the accumulation of NO. Myr-Akt stimulates the basal production of NO from BLMVEC, whereas cells infected with β-galactosidase or activation-deficient Akt released small amounts of NO that were close to the limits of detection (Fig. 4a). These results, in conjunction with the results in COS cells, indicate that phosphorylation of eNOS by Akt is sufficient to regulate NO production at resting levels of calcium. Indeed, NOS activity measured in lysates from myr-Akt-infected BLMVEC demonstrates that the sensitivity of the enzyme to activation by calcium, assayed at a fixed calmodulin concentration, is enhanced relative to NOS activity seen in BLMVEC infected with the β-galactosidase virus (Fig. 4b). The calcium sensitivity of NOS activity in cells infected with activation-deficient Akt was greatly suppressed relative to both myr-Akt and β-galactosidase-infected cells.

Figure 4.

Akt regulates the basal and stimulated production of NO in endothelial cells. a, BLMVEC were infected with adenoviral constructs (β-gal as control, myr-Akt and AA-Akt) and the amount of produced over 24 h was determined (n = 3). Inset: expression of eNOS and Akt. b, Lysates from adenovirus-infected BLMVEC were examined for NOS activity. Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were incubated with various concentrations of free calcium, and the NOS activity was determined (n = 3 experiments). c, BLMVEC were infected with adenoviruses as above followed by stimulation with VEGF (40 ng per ml) for 30 min and release was quantified by chemiluminescence. Data are presented as VEGF-stimulated release of after subtraction of basal levels; mean ± s.e.m., n = 4; asterisks represent significant differences (P < 0.05).

As mentioned above, treatment of endothelial cells with VEGF activates Akt23 and the release of NO through a mechanism partially blocked by inhibitors of PI(3)K15. Indeed, treatment of quiescent endothelial cells with VEGF induces Akt and eNOS phosphorylation (approximately twofold) concomitant with NO release (see Supplementary Information). To examine the functional link between VEGF as an agonist for NO release and Akt activation, BLMVEC were infected with adenoviruses for myr-Akt, AA-Akt or β-galactosidase, and VEGF-stimulated NO release was quantified. Infection of endothelial cells with myr-Akt enhances VEGF-driven NO production, whereas AA-Akt attenuates NO release (Fig. 4c). These results indicate that Akt may participate in the signal transduction events required for both basal and stimulated NO production in endothelial cells.

Our data show that Akt can phosphorylate eNOS on Ser 1179 and that phosphorylation enhances the ability of the enzyme to generate NO. Our results indicate that stimuli that promote NO release through a PI(3)K-dependent mechanism, independent of elevations in intracellular calcium (insulin and shear stress14,24,25), will stimulate Akt, thus permitting the phosphorylation and activation of eNOS at resting levels of calcium (Figs 1, 4). This can occur contemporaneously with the recruitment of the NOS regulatory protein Hsp9026, perhaps by stabilizing calmodulin previously bound to eNOS, thus resulting in NO release. In the case of G-protein-coupled receptors or receptor tyrosine kinases that mobilize intracellular calcium, we propose that agonist-dependent stimulation of PI(3)K11 and/or activation of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK)27 will activate Akt to phosphorylate eNOS concomitantly with the increase in cytoplasmic calcium. The calcium-dependent activation of calmodulin will stimulate CaMKK and the recruitment of calmodulin and perhaps Hsp90 to eNOS, facilitating rapid eNOS activation and the burst-like release of NO. How phosphorylation of eNOS by Akt enhances NO release is not known, but it is likely to be related to changes in the sensitivity of the enzyme to calcium-activated calmodulin. This may occur by the introduction of a negative charge, either by phosphate or aspartate, thereby ‘opening up’ the structure (perhaps by removing the auto-inhibitory loop of eNOS28) and thus permitting activated calmodulin binding at lower calcium concentrations. Thus, regulation of NO production by Akt-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS may provide a novel therapeutic target for the design of drugs aimed at improving endothelial function in cardiovascular diseases associated with dysfunction in the synthesis or biological activity of NO, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, heart failure and diabetes.

Methods

Cell transfections

The bovine eNOS, human iNOS and rat nNOS cDNAs in pcDNA3 and HA-tagged wild-type Akt, Akt (K179M) and myr-Akt in pCMV6 were generated by standard cloning methods. The myr-nNOS in pcDNA3 was generated by PCR, incorporating a new amino terminus containing the eNOS N-myristoylation consensus site (MGNLKSVG) fused in frame to the second amino acid of the nNOS coding sequence. In preliminary experiments in COS cells, this construct was N-myristoylated based on incorporation of 3H-myristic acid (unlike native nNOS) and resulted in approximately 60% of the total protein being targeted into the membrane fraction of cells (only 5–10% of nNOS was membrane associated in COS cells). The putative Akt phosphorylation sites in eNOS were mutated using the Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturers instructions. All mutants were verified by DNA sequencing. We plated COS-7 cells (100 mm dish) and transfected them with the NOS (7.5–30 μg) and Akt (1 μg) plasmids using calcium phosphate. To balance all transfections, the expression vector for β-galactosidase cDNA was used. 24–48 h after transfection, the expression of appropriate proteins (40–80 μg) were confirmed by western blot analysis using eNOS mAb (9D10, Zymed), HA mAb (12CA5, Boehringer Mannheim), iNOS pAb (Zymed Laboratories) or nNOS mAb (Zymed Laboratories).

NO release from transfected COS cells

24-48 h after transfection, media were processed for the measurement of nitrite (), the stable breakdown product of NO in aqueous solution, by NO-specific chemiluminescence as described20. Media were deproteinized and samples containing were refluxed in glacial acetic acid containing sodium iodide. Under these conditions, was quantitatively reduced to NO which was quantified by a chemiluminescence detector after reaction with ozone in a NO analyser (Sievers). In all experiments, release was inhibitable by a NOS inhibitor. In addition, release from cells transfected with the β-galactosidase cDNA was subtracted to control for background levels of found in serum or media. In some experiments, we used cGMP accumulation in COS cells as a bioassay for the production of NO as described.

NOS activity assays

We used the conversion of 3H-L-arginine to 3H-L-citrulline to determine NOS activity in COS cell or endothelial cell lysates as described26.

Phosphorylation studies in vivo and In vitro

For in vivo phosphorylation studies, COS cells were transfected with the cDNAs for wild-type or S635/1179A eNOS and HA-Akt overnight. 36 h after transfection, we placed cells into dialysed serum-replete, phosphate-free Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 80 μCi per ml of 32P orthophosphoric acid for 3 h. Some cells were pretreated with wortmannin (500 nM) in the phosphate-free medium for 1 h and during the labelling. The lysates were collected and the eNOS was solubilized and partially purified by ADP Sepharose-affinity chromatography as previously described. 32P incorporation into eNOS was visualized after SDS–PAGE (7.5%) by autoradiography, and the amount of eNOS protein was verified by western blotting for eNOS. For in vitro phosphorylation studies, we incubated recombinant eNOS purified from Escherichia Coli with wild-type or kinase-inactive Akt immunoprecipitated from transfected COS cells. eNOS was incubated with 32P γ-ATP (2 μl, specific activity 3000Ci per mmol), ATP (50 μM) and DTT (1 mM), in a buffer containing HEPES (20 mM, pH = 7.4), MnCl2 (10 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM) and immunoprecipitated Akt for 20 min at room temperature. In experiments examining the in vitro phosphorylation of wild-type and mutant eNOS we incubated recombinant Akt (1 μg) purified from baculovirus-infected SF9 cells with wild-type or S1179A eNOS (2.4 μg, purified from E. coli) using essentially the same conditions as above. Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and 32P incorporation and the amount of protein was determined by Coomassie staining as above. In studies identifying the labelled eNOS peptide, we incubated immunoprecipitated Akt with recombinant eNOS as above. The sample was run on SDS-PAGE and the eNOS band digested in gel, and the resultant tryptic fragments were purified by RP-HPLC. Peptide mass and 32P incorporation were monitored and the prominent labelled peak was further analysed by mass spectrometry. In other experiments, peptides corresponding to the potential Akt phosphorylation site were synthesized, purified by HPLC and verified by mass spectrometry (W. M. Keck Biotechnology Resource Center, Yale University School of Medicine). The wild-type peptide was 1174RIRTQSFSLQERHLRGAVPWA1194 and the mutant peptide was identical except that Ser 1179 was changed to alanine. In vitro kinase reactions were done essentially as described above by incubating peptides (25 μg) with recombinant Akt (1 μg). Reactions were then spotted onto phosphocellulose filters and the amount of phosphate incorporated was measured by Cerenkov counting.

Adenoviral infections and NO release in endothelial cells

We cultured BLMVEC in either 100 mm dishes (for basal NO release and NOS activity assays) or C6 well plates (for stimulated NO) as described18. BLMVEC were infected with 200 MOI of adenovirus containing the β-galactosidase29, HA-tagged, inactive phosphorylation mutant Akt (AA-Akt30) or carboxy-terminal HA-tagged constitutively active Akt (myr-Akt) for 4 h. The virus was removed and cells left to recover for 18 h in complete medium. In preliminary experiments with the β-galactosidase virus, these conditions were optimal for infecting 100% of the cultures. For measurement of basal NO production, medium was collected 24 h after the initial infection with virus. For measurement of stimulated NO release, cells were then washed with serum-free medium followed by stimulation with VEGF (40 ng ml−1) for 30 min. In some experiments, we determined the calcium dependency of NOS 24 h after adenoviral infection. Infected cells were lysed in NOS assay buffer containing 1% NP40, and detergent soluble material was used for activity assays. Lysates were incubated with EGTA-buffered calcium to yield appropriate amounts of free calcium in the incubation.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Comparisons were made using a two-tailed Student’s t-test or ANOVA with a post-hoc test where appropriate. Differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Martasek and B. S. Masters for recombinant eNOS; J. Liu for constructing and characterizing the myr-nNOS construct; D. Bredt and T. Billiar for NOS cDNAs; T. Zioncheck for human VEGF; Y. Chen for generating the eNOS S1179A E. Coli expression construct; and K. Williams, M. LoPresti and K. Stone in the Keck Facility for their help with identification of the eNOS phosphopeptides. This work was supported by grants from the NIH and American Heart Association. W.C.S. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. J.P.G. is supported by fellowships from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and from FCAR.

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available on Nature’s World-Wide Web site (http://www.nature.com) or as paper copy from the London editorial office of Nature.

Note added in proof: While in review, a recent paper has demonstrated that AMP-activated kinase can phosphorylate human eNOS on Ser 1177, in vitro (Chen et al. FEBS Lett., 443, 285–289 (1999)).

References

- 1.Shesely EG, et al. Elevated blood pressures in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13176–13181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang PL, et al. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;377:239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudic RD, et al. Direct evidence for the importance of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in vascular remodeling. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:731–736. doi: 10.1172/JCI1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murohara T, et al. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:2567–2578. doi: 10.1172/JCI1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michel T, Li GK, Busconi L. Phosphorylation and subcellular translocation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6252–6256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Cardena G, Fan R, Stern DF, Liu J, Sessa WC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation and interacts with caveolin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:27237–27240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corson MA, et al. Phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in response to fluid shear stress. Circ. Res. 1996;79:984–991. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.5.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffer PJ, Jin J, Woodgett JR. Protein kinase B (c-Akt): a multifunctional mediator of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Biochem. J. 1998;335:1–13. doi: 10.1042/bj3350001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downward J. Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murga C, Laguinge L, Wetzker R, Cuadrado A, Gutkind JS. Activation of Akt/protein kinase B by G protein-coupled receptors. A role for alpha and beta gamma subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins acting through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19080–19085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimmeler S, Assmus B, Hermann C, Haendeler J, Zeiher AM. Fluid shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of Akt in human endothelial cells: involvement in suppression of apoptosis. Circ. Res. 1998;83:334–341. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardone MH, et al. Regulation of cell death protease caspase-9 by phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng G, Quon MJ. Insulin-stimulated production of nitric oxide is inhibited by wortmannin. Direct measurement in vascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:894–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI118871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papapetropoulos A, Garcia-Cardena G, Madri JA, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:3131–3139. doi: 10.1172/JCI119868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parenti A, et al. Nitric oxide is an upstream signal of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 activation in postcapillary endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:4220–4226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Hughes TE, Sessa WC. The first 35 amino acids and fatty acylation sites determine the molecular targeting of endothelial nitric oxide synthase into the golgi region of cells: A green fluorescent protein study. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1525–1535. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Cardeña G, Oh P, Liu J, Schnitzer JE, Sessa WC. Targeting of nitric oxide synthase to endothelial cell caveolae via palmitoylation: Implications for nitric oxide signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaul PW, et al. Acylation targets emdothelial nitric-oxide synthase to plasmalemmal caveolae. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6518–6522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sessa WC, et al. The Golgi association of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is necessary for the efficient synthesis of nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17641–17644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Garcia-Cardena G, Sessa WC. Palmitoylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is necessary for optimal stimulated release of nitric oxide: implications for caveolae localization. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13277–13281. doi: 10.1021/bi961720e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantor DB, et al. A role for endothelial NO synthase in LTP revealed by adenovirus-mediated inhibition and rescue. Science. 1996;274:1744–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerber HP, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-Kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Requirement for flk-1/kdr activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30336–30343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuchan MJ, Frangos JA. Role of calcium and calmodulin in flow-induced nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:C628–636. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.3.C628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayajiki K, Kindermann M, Hecker M, Fleming I, Busse R. Intracellular pH and tyrosine phosphorylation but not calcium determine shear stress-induced nitric oxide production in native endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 1996;78:750–758. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Cardena G, et al. Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature. 1998;392:821–824. doi: 10.1038/33934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yano S, Tokumitsu H, Soderling TR. Calcium promotes cell survival through CaM-K kinase activation of the protein kinase-B pathway. Nature. 1998;396:584–587. doi: 10.1038/25147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salerno JC, et al. An autoinhibitory control element defines calcium-regulated isoforms of nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:29769–29777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith RC, et al. p21CIP1-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation by overexpression of the gax homeodomain gene. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1674–1689. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alessi DR, et al. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.