Abstract

Context

Epidemiologic studies of adults show that DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a highly prevalent and seriously impairing disorder. Although retrospective reports in these studies suggest that IED typically begins in childhood, no previous epidemiologic research has directly examined the prevalence or correlates of IED among youth.

Objective

To present epidemiologic data on the prevalence and correlates of IED among US adolescents in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.

Design

United States survey of adolescent (age, 13–17 years) DSM-IV anxiety, mood, behavior, and substance disorders.

Setting

Dual-frame household-school samples.

Participants

A total of 6483 adolescents (interviews) and parents (questionnaires).

Main Outcome Measures

The DSM-IV disorders were assessed with the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).

Results

Nearly two-thirds of adolescents (63.3%) reported lifetime anger attacks that involved destroying property, threatening violence, or engaging in violence. Of these, 7.8% met DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for lifetime IED. Intermittent explosive disorder had an early age at onset (mean age, 12.0 years) and was highly persistent, as indicated by 80.1% of lifetime cases (6.2% of all respondents) meeting 12-month criteria for IED. Injuries related to IED requiring medical attention reportedly occurred 52.5 times per 100 lifetime cases. In addition, IED was significantly comorbid with a wide range of DSM-IV/CIDI mood, anxiety, and substance disorders, with 63.9% of lifetime cases meeting criteria for another such disorder. Although more than one-third (37.8%) of adolescents with 12-month IED received treatment for emotional problems in the year before the interview, only 6.5% of respondents with 12-month IED were treated specifically for anger.

Conclusions

Intermittent explosive disorder is a highly prevalent, persistent, and seriously impairing adolescent mental disorder that is both understudied and undertreated. Research is needed to uncover risk and protective factors for the disorder, develop strategies for screening and early detection, and identify effective treatments.

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is defined in the DSM-IV1 as a disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of aggression involving violence or destruction of property out of proportion to provocation or precipitating stressors. The attacks must involve failure to control aggressive impulses and not be accounted for by another mental disorder or physiological effects of a substance. Intermittent explosive disorder is the only DSM-IV disorder for which the core feature is impulsive aggression.

Few epidemiologic studies have examined IED prevalence or correlates, and these focused almost exclusively on adults. A survey of patients in a university private practice clinic reported a 3.1% point prevalence of IED.2 A community study in a small nonprobability subsample of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-up study found lifetime and 1-month IED prevalence estimates of 4.0% and 1.6%, respectively.3 The only national data on IED were collected in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).4 Because the DSM-IV does not provide diagnostic thresholds for frequency, severity, or temporal clustering of anger attacks required for diagnosis, IED was defined using both narrow and broad interpretations of DSM-IV criteria, with lifetime prevalence estimated at 5.4% to 7.3%. Lifetime prevalence was much higher among younger than older respondents. Retrospective reports3,4 suggested that IED typically begins in childhood or adolescence and has a persistent course associated with significant impairment and low treatment. However, although uncontrollable anger is known to occur more often among youths than adults,5 we are aware of only one study6 that examined IED among children or adolescents. That study found IED to be the most common impulse-control disorder in a sample of 102 adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Information on the general population prevalence and correlates of adolescent IED would be useful for both research and public health planning purposes. The current report presents such data, based on the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), a national general population survey of DSM-IV mental disorders among US adolescents.

METHODS

SAMPLE

The NCS-A was carried out between February 5, 2001, and January 31, 2004, in dual-frame household and school samples of adolescents aged 13 to 17 years (face-to-face interviews) and their parents (self-administered questionnaires [SAQs]).7,8 The household sample (86.8% response rate) included 904 adolescents (879 in school and 25 who had dropped out of school) from households that participated in the NCS-R, a national survey of adults.9 The school sample (82.6% response rate) included 9244 adolescents from a representative sample of schools in the NCS-R counties. The proportion of initially selected schools that participated in the NCS-A was low (28.0%). Matched replacement schools were selected for schools that declined to participate. A comparison of household sample respondents who attended nonparticipating schools with school sample respondents from replacement schools found no evidence of bias in estimates of prevalence or correlates of mental disorders.8 One parent or guardian was asked to complete an SAQ about the adolescent’s developmental history and mental health. The SAQ response rate, conditional on adolescent participation, was 82.5% in the household sample and 83.7% in the school sample. This report focuses on the 6483 adolescent-parent pairs for whom data were available from adolescent interviews and parent SAQs.

Written informed consent was obtained from parents before adolescents were approached. Written assent from adolescents was then obtained before surveying either the adolescents or parents. Each respondent was given $50 for participation. These recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the human subjects committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. Once the survey was completed, cases were weighted for variation in within-household probability of selection in the household sample and residual discrepancies between sample and population sociodemographic and geographic distributions. The household and school samples were then merged with sums of weights proportional to relative sample sizes adjusted for design effects in estimating disorder prevalence. These weighting procedures are detailed elsewhere.7,8 The weighted sociodemographic distributions of the composite sample closely approximate those of the census population.10

MEASURES

Diagnostic Assessment

Adolescents were administered a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a fully structured interview designed to be administered by trained lay persons.11 Previous factor analysis of lifetime DSM-IV disorders in the NCS-A found that they differentiated into 4 classes12: fear disorders (agoraphobia without history of panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia), distress disorders (major depressive disorder/dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and separation anxiety disorder), behavior disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], and conduct disorder [CD]), and substance abuse (alcohol abuse and drug abuse, with or without dependence). Bipolar disorder (BPD), which was also assessed in the surveys, did not have a strong unique loading on any of these 4 factors.

Parents provided diagnostic information about major depression/dysthymia, ADHD, ODD, and CD based on the fact that these are the disorders for which parent reports have been shown13,14 to play the largest role in diagnosis. Parent and adolescent reports were combined at the symptom level using an “or” rule: a symptom was considered present if it was endorsed by either respondent. All diagnoses were made using DSM-IV organic exclusion rules. All but 2 diagnoses were made using DSM-IV diagnostic hierarchy rules. The exceptions were ODD, which was defined with or without CD, and substance abuse, which was defined with or without dependence.

In a blinded design, a clinical reappraisal study reinter-viewed a subsample of NCS-A respondents with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Lifetime Version (K-SADS).15 As reported in more detail,16 concordance between CIDI/SAQ and K-SADS diagnoses was good, with area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) curve of 0.81 to 0.94 for fear disorders, 0.79 to 0.87 for distress disorders, 0.78 to 0.98 for behavior disorders, 0.56 to 0.98 for substance disorders, and 0.87 for any disorder. As in other studies, parent and adolescent reports contributed to AUC when both were assessed,17 with values based on respective adolescent, parent, and combined reports of 0.75, 0.71, and 0.87 for depression/dysthymia; 0.57, 0.71, and 0.78 for ADHD; 0.71, 0.66, and 0.85 for ODD; and 0.59, 0.96, and 0.98 for CD. Diagnoses of IED were not validated because IED is not assessed in the K-SADS.

The CIDI assessed IED based on DSM-IV criteria. Criterion A requires several “discrete episodes of failure to resist aggressive impulses that result in serious assaultive acts or destruction of property.”1(p663) This was operationalized in the CIDI with questions about anger attacks “when all of a sudden you lost control and … ” (1) “broke or smashed something worth more than a few dollars,” (2) “hit or tried to hurt someone,” and (3) “threatened to hit or hurt someone.” The respondent was required to report 3 or more such attacks in his/her lifetime to meet this criterion. We also created a narrow definition that required 3 attacks in a single year, with at least 1 attack involving interpersonal violence or property destruction. Although this temporal clustering requirement is not specified in the DSM-IV, it has been used in clinical studies of IED3 and in the NCS-R.4 Three successively more stringent definitions were also used to define 12-month IED. The broad definition required 3 lifetime attacks with at least 1 attack in the past 12 months. The intermediate definition required 3 lifetime attacks in the same year with at least 1 attack in the past 12 months. The narrow definition required 3 attacks in the past 12 months with at least 1 attack involving interpersonal violence or property destruction.

The DSM-IV criterion B for IED requires that the aggression is “grossly out of proportion to any precipitating psychosocial stressor.”1(pp663–664) This was operationalized in the CIDI by requiring the respondent to report that he or she “got a lot more angry than most people would have been in the same situation,” that the attacks occurred “without good reason,” or that the attacks occurred “in situations where most people would not have had an anger attack.”

The DSM-IV criterion C for IED requires that the “aggressive episodes are not better accounted for by another mental disorder and are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition.”1(p664) This criterion was partially operationalized in the CIDI with a series of questions that determined whether anger attacks occurred only in the context of a substance use disorder, depression, or organic causes. The substance use and depression questions asked respondents if their anger attacks usually occurred when they had been drinking or using drugs or when they were in an episode of being sad or depressed. Positive responses were followed with probes about whether the attacks ever occurred at times when the respondent was not under the influence of alcohol or drugs or not depressed. The questions about organic causes were as follows: “Anger attacks can sometimes be caused by physical illnesses such as epilepsy or a head injury or by the use of medications. Were your anger attacks ever caused by physical illness or medications?” Positive responses were followed with probes that inquired about the nature of the illness and/or medication and whether the respondent ever had attacks other than during the course of the illness or under the influence of the medication. If not, the case was considered to be the result of an organic cause.

Although the CIDI did not include parallel questions that excluded respondents whose anger attacks occurred in the course of BPD, we excluded all respondents with a history of BPD based on the fact that anger attacks occur in BPD and on evidence that IED has a particularly strong relationship with BPD.18–20 In addition, because impulsive aggression is a common feature in disruptive behavior disorders such as ADHD, ODD, and CD,21,22 we excluded respondents having a history of ADHD with hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, ODD, or CD with overt features. These exclusions might have been overly inclusive, but we concluded that this conservative approach was appropriate in light of controversy regarding the diagnosis of IED.

Clinical Features

Measures of the onset and course of IED were based on retrospective reports about age at onset (AAO), number of lifetime attacks, number of years with attacks, and number of attacks in the 12 months before the interview. Lifetime impairment was assessed with questions about the financial value of all things the respondent ever broke or damaged during an anger attack and the number of times either the respondent or someone else had to seek medical attention because of an injury caused by the respondent’s anger attacks. Twelve-month impairment was assessed with questions about the extent to which the respondent’s anger attacks interfered with his or her life and activities in the worst month of the year based on a modified version of the Sheehan Disability Scales23 that used a 0 to 10 visual analog scoring scheme to assess how much a focal disorder interfered with home life, school or work, family relationships, and social life. Response options were none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), and very severe (10).

Sociodemographics

The sociodemographic variables included in the analysis were sex, age (13, 14, 15–16, and 17–18 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), parent’s educational level (less than high school, high school graduate, some postsecondary schooling, and college graduate), number of biological parents living with the respondent, number of siblings, birth order, region of the country (Northeast, Midwest, West, and South), and urbanicity (central city of a major metropolitan area, other urbanized area, and rural area).

ANALYSIS METHODS

Prevalence was estimated with cross-tabulations. Cumulative lifetime AAO curves were calculated using the actuarial method.24 Associations of IED with sociodemographics and comorbid DSM-IV disorders were examined using logistic regression analysis. Impairment was examined using analysis of variance. Logistic regression coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated to create odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Standard errors were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method in commercial software (SUDAAN, version 8.01; Research Triangle Institute) to account for sample weights and clustering. Statistical significance was evaluated using 2-sided tests, with significance set at P < .05.

RESULTS

PREVALENCE OF ANGER ATTACKS

Nearly two-thirds (63.3%) of adolescents in the NCS-A reported at least 1 lifetime anger attack involving destroying property, threatening violence, or engaging in violence (Table 1). More detailed analyses (results available on request) found attacks involving threats of violence to be the most common (57.9%), followed by attacks involving violence (39.3%) and destruction of property (31.6%). Most respondents who reported anger attacks (72.5%) had attacks that involved more than 1 of these 3 behaviors.

Table 1.

Distribution of Lifetime Anger Attacks Among 6483 Adolescents in the NCS-A

| Characteristic | Prevalence in the Total Sample (SE) | Mean (SE) No. of Attacks | Extreme, Range (IQR)a | Total No. of Attacksb | Proportion of All Attacks in the Population, % (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anger attacks among respondents who do not qualify for a diagnosis of IED | |||||

| 1–2 Lifetime attacks | 29.3 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.0) | 1–2 (1–2) | 43.3 | 5.7 (0.5) |

| ≥3 Attacks not out of proportion | 8.0 (0.6) | 12.3 (1.5) | 3–500 (3–10) | 98.4 | 12.9 (1.8) |

| ≥3 Out-of-proportion attacks not out of control | 12.1 (0.7) | 16.2 (2.4) | 3–500 (3–10) | 195.0 | 25.5 (4.0) |

| ≥3 Out-of-proportion/out-of-control attacks disqualified because of diagnostic hierarchy and/or organic exclusions | 6.2 (0.6) | 47.0 (7.7) | 3–500 (5–40) | 290.3 | 38.0 (4.5) |

| Anger attacks among respondents who qualify for a diagnosis of IEDc | |||||

| Broadly defined IED | 7.8 (0.7) | 17.6 (3.6) | 3–500 (4–10) | 137.0 | 17.9 (4.0) |

| Narrowly defined IED | 5.3 (0.5) | 22.6 (4.8) | 3500 (5–20) | 118.7 | 15.5 (0.1) |

| Broadly defined–only IED | 2.5 (0.4) | 7.2 (2.0) | 3–50 (3–5) | 18.3 | 2.4 (0.1) |

| Prevalence of attacks within the whole population | 63.3 (1.0) | 12.1 (0.9) | 1–500 (2–5) | 764.1 | 100.0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations: IED, intermittent explosive disorder; IQR, interquartile range; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent supplement.

25th to 75th percentiles of the frequency distribution.

Prevalence × mean.

Narrowly defined, 3 or more annual attacks in at least 1 year of life, including physical assault or property damage; broadly defined–only, 3 or more lifetime attacks either without ever having as many as 3 attacks in a single year or 3 or more annual attacks in at least 1 year but attacks involved only threatening someone; broadly defined, narrowly defined or broadly defined–only.

Nearly half of those who reported attacks (29.3% of the sample) had only 1 or 2 lifetime attacks, and another third (20.1% of the sample) only had attacks that were either proportional in response to provoking circumstances (8% of the sample) or not out of control (12.1% of the sample). The remaining, approximately one-fifth of adolescents with anger attacks, were made up of those with IED (7.8% of the sample) and those for whom a diagnosis of IED was excluded because of diagnostic hierarchy rules or organic cause exclusions (6.2% of the sample). The latter respondents had a much higher mean number of anger attacks (47.0, representing 38.0% of all attacks reported in the sample) than did respondents with IED (17.6, representing 17.9% of all attacks reported in the sample).

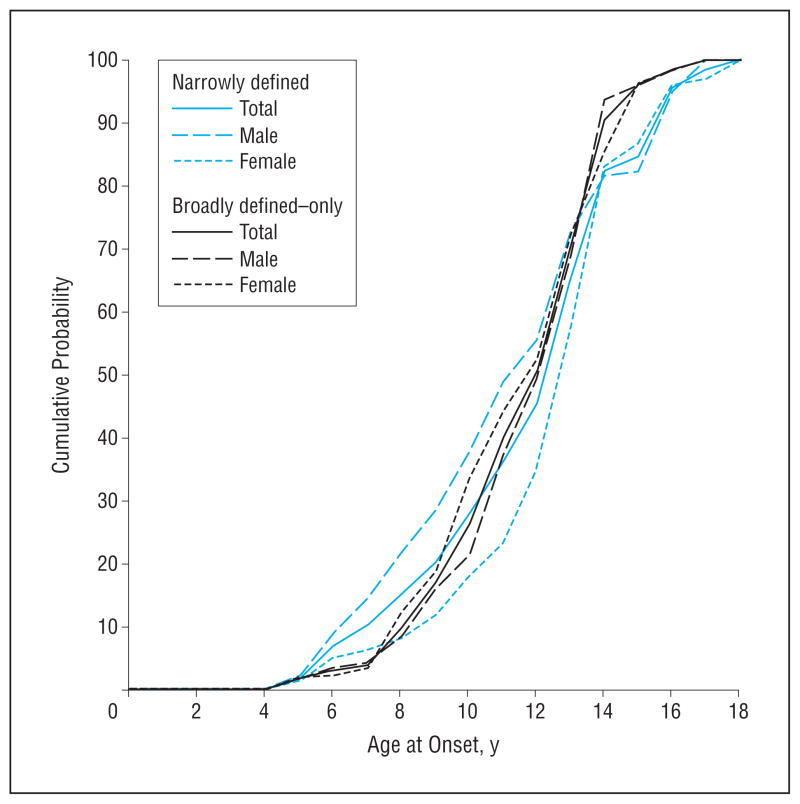

Estimated lifetime prevalence (SE) of narrowly defined IED was 5.3% (0.5%). Estimated 12-month prevalence was 6.2% (0.7%) using the broad definition, 4.5% (0.4%) using intermediate definition, and 1.7% (0.4%) using the narrow definition. The ratio of 12-month to lifetime prevalence provides an estimate of persistence across the age range of the sample. This ratio was 80.1% (ie, 6.2%: 7.8%) for broadly defined IED, suggesting that IED is persistent throughout adolescence. Mean AAO was in early adolescence for both broadly defined (12.0 years) and narrowly defined (12.5 years) IED. The full AAO distributions were similar for broadly defined–only and narrowly defined lifetime cases (Figure).

Figure.

Age-at-onset distributions of narrowly defined and broadly defined–only lifetime DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder (N = 6483).

LIFETIME PERSISTENCE AND SEVERITY

Narrowly defined IED was significantly more persistent than broadly defined–only IED, as indicated by a higher mean number of lifetime attacks (22.6 vs 7.2; , P =.004), mean years with attacks (4.3 vs 3.3; , P=.02), and highest number of attacks in a single year (24.9 vs 3.1; , P =.01) (Table 2). Narrowly defined cases also appeared to be more severe than broadly defined–only cases because of the higher mean monetary value of objects damaged ($250.50 vs $97.50; , P =.05). However, mean lifetime property damage per attack did not differ significantly for narrowly defined ($15) vs broadly defined–only IED ($14; , P =.79). In addition, there was no significant difference between narrowly defined and broadly defined–only IED in the number of injuries requiring medical attention per 100 attacks (10.6 vs 4.2; , P =.24).

Table 2.

Course and Severity of Lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI Intermittent Explosive Disorder Among 6483 Adolescents in the NCS-A

| Characteristic | Mean (SE)

|

Narrowly Defined vs Broadly Defined–Only b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrowly Defineda (n = 327) | Broadly Defined–Onlya (n = 147) | Broadly Defineda (n = 474) | ||

| Course | ||||

| No. of lifetime attacks | 22.6 (4.8) | 7.2 (2.0) | 17.6 (3.1) | 8.3c |

| No. of years with attacks | 4.3 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.2) | 5.2 |

| Highest No. of annual attacks | 24.9 (8.3) | 3.1 (0.6) | 17.8 (5.2) | 6.6c |

| Severity | ||||

| Property damage, $d | 250.5 (75.8) | 97.5 (13.9) | 208.9 (56.4) | 3.8 |

| Medical attention required (per 100 cases)e | 64.1 (25.4) | 20.1 (9.5) | 52.5 (18.9) | 2.7 |

Abbreviations: CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.

Narrowly defined, 3 or more annual attacks in at least 1 year, including physical assault or property damage; broadly defined–only, 3 or more lifetime attacks either without ever having as many as 3 attacks in a single year or having 3 or more annual attacks in at least 1 year but the attacks involved only threatening someone; broadly defined (includes all intermittent explosive disorder cases), narrowly defined or broadly defined–only.

Significance test with bivariate linear regression models to test the difference in mean between narrowly defined and broadly defined–only cases. No controls were used.

Significant difference in means at P < .05, 2-sided test.

Estimated cost of all property ever damaged or broken in an anger attack.

Number of times during an anger attack that someone was hurt enough to need medical attention per 100 cases of intermittent explosive disorder.

TWELVE-MONTH PERSISTENCE AND SEVERITY

The mean number of past-year anger attacks was higher for 12-month narrowly defined (18.3) than intermediately defined–only (1.6) or broadly defined–only (2.5) IED ( , P < .001) (Table 3). The same pattern held for number of weeks with attacks ( , P < .001). A higher proportion of narrowly defined (31.3%) and intermediately defined–only (27.9%) than broadly defined–only (13.2%) cases reported severe 12-month role impairment of some type resulting from anger attacks. These differences were not statistically significant ( , P =.10), although the IED subsamples differed significantly in impairments in social life ( , P < .001) but not in other domains of functioning ( , P=.96–.10).

Table 3.

Duration and Impairment of 12-Month DSM-IV/CIDI Intermittent Explosive Disorder Among 6483 Adolescents in the NCS-A

| Narrowly Defineda (n = 216) | Intermediately Defined–Onlya (n = 72) | Broadly Defined–Onlya (n = 97) | Broadly Defineda (n = 385) |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-mo Persistence, mean (SE) | ||||||

| No. of 12-mo attacks | 18.3 (4.8) | 1.6 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.4) | 10.4 (2.5) | 68.8c | |

| No. of weeks with attacks | 8.3 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.1) | 2.0 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.5) | 62.0c | |

| Severe role impairment (Sheehan Disability Scales), % (SE) | ||||||

| Home | 4.8 (1.9) | 5.7 (4.1) | 4.3 (3.5) | 4.8 (1.9) | 0.1 | |

| Work | 7.4 (2.3) | 9.8 (5.9) | 3.5 (2.2) | 6.8 (1.7) | 1.6 | |

| Interpersonal | 14.6 (2.6) | 22.5 (6.6) | 6.5 (4.2) | 14.0 (2.7) | 3.2 | |

| Social | 16.5 (5.0) | 5.4 (2.9) | 1.4 (0.9) | 10.0 (2.9) | 14.8c | |

| Summary | 31.3 (4.6) | 27.9 (7.0) | 13.2 (5.8) | 25.6 (3.8) | 4.6 | |

Abbreviations: CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.

Narrowly defined, 3 or more 12-mo attacks involving physical assault or property damage; intermediately defined–only, 3 or more lifetime attacks in a single year (lifetime narrow) and either one or two 12-mo attacks, or 3 + 12-mo attacks but attacks only involved threatening someone; broadly defined–only, 3 or more lifetime attacks without ever having more than 3 in a single year (lifetime broad), and having one or two 12-mo attacks; broadly defined (includes all intermittent explosive disorder cases), narrowly defined or intermediately defined–only or broadly defined–only.

Narrowly defined vs intermediately defined–only vs broadly defined–only. The top 2 rows (number of 12-mo attacks, number of weeks with attacks) are continuous variables, and a bivariate linear regression model was used to assess the differences across subsamples. The final 5 rows are dichotomous variables, and a bivariate logistic regression model was used to assess the differences across subsamples. No controls were used in these models.

Significant difference at P < .05, 2-sided test.

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CORRELATES

The only statistically significant sociodemographic correlates of broadly defined lifetime IED were the number of siblings and living with fewer than 2 biological parents, both of which were positively related to IED (detailed results available on request). Sex was not a significant correlate. Among respondents who met broad lifetime criteria, parental educational level and number of siblings distinguished narrowly defined from broadly defined–only cases, with respondents whose parents had fewer years of education and who had no siblings being more likely than others to meet criteria for narrowly defined lifetime IED. The number of siblings and number of biological parents living with the respondent were also associated with 12-month persistence among lifetime cases, with greater persistence observed among respondents with 1 to 2 siblings than among those with more siblings and among those not living than among those living with biological parents (detailed results available on request).

COMORBIDITY

Most (63.9%) respondents with broadly defined lifetime IED met the criteria for at least 1 additional lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorder (Table 4). After controlling for sociodemographics, comorbidity was significantly elevated for all disorders considered in this study other than major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and alcohol abuse, with ORs in the range of 1.5 to 5.1. Associations of IED were strongest with fear disorders (OR, 2.6), followed by substance abuse and distress disorders (OR,1.5–1.6). Odds ratios were consistently higher for narrowly defined than broadly defined–only IED, although the difference in ORs was significant only for substance abuse.

Table 4.

Lifetime Comorbidity of DSM-IV/CIDI IED With Other DSM-IV/CIDI Disorders Among 6483 Adolescents in the NCS-Aa

| Disorder | Broadly Definedb

|

Narrowly Definedb,c: Broadly Defined–Onlyb,c

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE)d | % (SE)e | OR (95% CI)f | % (SE)g | % (SE)h | OR (95% CI)i | |

| Fear | ||||||

| Agoraphobia | 9.7 (2.6) | 28.5 (6.1) | 5.1 (2.8–9.2)j | 10.7 (4.1) | 21.2 (6.8) | 1.1 (0.3–4.5) |

| Social phobia | 16.0 (2.9) | 14.7 (2.9) | 2.2 (1.3–3.7)j | 16.6 (4.1) | 10.3 (2.7) | 1.3 (0.5–3.3) |

| Specific phobia | 32.7 (3.5) | 12.8 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.5–2.9)j | 36.0 (3.8) | 9.5 (1.3) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) |

| Panic disorder | 7.2 (2.2) | 23.3 (6.8) | 3.8 (1.8–7.9)j | 8.6 (2.9) | 18.7 (6.5) | 2.5 (0.3–24.0) |

| Any fear disorder | 46.0 (3.6) | 13.7 (1.8) | 2.6 (2.0–3.5)j | 50.0 (4.5) | 10.1 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) |

| Distress | ||||||

| Major depression or dysthymia | 21.6 (2.2) | 9.1 (1.2) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 23.0 (3.1) | 6.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 2.6 (1.0) | 6.3 (2.5) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 3.1 (1.4) | 5.2 (2.3) | 2.6 (0.5–14.5) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 6.5 (2.0) | 10.8 (3.1) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 6.4 (3.2) | 7.2 (3.3) | 0.7 (0.1–7.1) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 12.9 (2.6) | 13.3 (2.5) | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 13.6 (4.5) | 9.5 (2.8) | 1.1 (0.2–5.4) |

| Any distress disorder | 34.3 (2.8) | 10.4 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0)j | 35.9 (4.9) | 7.3 (1.1) | 1.4 (0.5–3.4) |

| Substance use | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 8.1 (1.7) | 10.3 (2.4) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 10.2 (2.5) | 8.8 (2.2) | 2.7 (0.9–7.7) |

| Drug abuse or dependence | 14.4 (2.8) | 12.7 (2.7) | 1.8 (1.0–3.1)j | 17.4 (3.8) | 10.3 (2.3) | 2.2 (1.0–4.8) |

| Any substance disorder | 17.1 (3.0) | 11.7 (2.2) | 1.6 (1.0–2.7) | 21.1 (4.1) | 9.7 (1.9) | 2.8 (1.2–6.4)j |

| Any disorder | ||||||

| ≥1 Disorder | 63.9 (3.9) | 11.3 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.6–3.5)j | 68.5 (4.6) | 8.2 (1.1) | 1.9 (0.9–4.0) |

| 1 Disorder | 27.7 (3.3) | 9.3 (1.6) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 27.4 (3.3) | 6.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) |

| 2 Disorders | 19.3 (2.4) | 13.4 (2.1) | 2.0 (1.4–2.8)j | 22.2 (3.4) | 10.4 (2.1) | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) |

| ≥3 Disorders | 16.9 (2.5) | 13.4 (2.1) | 1.9 (1.3–2.9)j | 18.9 (4.2) | 10.1 (2.1) | 1.3 (0.4–4.9) |

| No. of cases in the analysis | 6483 | 474 | ||||

Abbreviations: CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; IED, intermittent explosive disorder; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement; OR, odds ratio.

Lifetime history of disruptive behavior disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, oppositional defiant disorder, or conduct disorder with overt features, was an exclusion criteria for IED. This rule artificially rules out the possibility of comorbidity between IED and disruptive behavior disorders. See the “Methods” section for details.

Narrowly defined, 3 or more annual attacks in at least 1 year of life, including physical assault or property damage; broadly defined–only, 3 or more lifetime attacks either without ever having as many as 3 attacks in a single year or 3 or more annual attacks in at least 1 year but attacks only involved threatening someone; broadly defined (includes all IED cases), narrowly defined or broadly defined–only.

Narrowly defined: broadly defined–only, comparing lifetime narrowly defined with lifetime broadly defined–only by restricting the sample to cases with either of these 2 definitions and treating lifetime broadly defined–only as the reference category.

Prevalence of the row variables among the column variables. For example, in the first row, % represents the percentage of cases among lifetime broadly defined IED with agoraphobia.

Prevalence of broadly defined IED among the row variables. For example, in the first row, % represents the percentage of cases of lifetime broadly defined IED among those with lifetime agoraphobia.

Bivariate logistic regression models controlling for age, sex, race, region, urbanicity, parent educational level, number of biological parents, birth order, and number of siblings to predict lifetime broadly defined IED with other DSM-IV disorders.

Prevalence of the row variables among lifetime narrowly defined IED. For example, in the first row, % represents the percentage of cases among lifetime narrowly defined IED with agoraphobia.

Prevalence of narrowly defined IED among the row variables. For example, in the first row, % represents the percentage of cases of lifetime narrowly defined IED among those with lifetime agoraphobia.

Bivariate logistic regression models controlling for age, sex, race, region, urbanicity, parent educational level, number of biological parents, birth order, and number of siblings to predict lifetime narrowly defined IED with other DSM-IV disorders. Subsample is restricted to cases with either lifetime narrowly defined IED or lifetime broadly defined–only IED; lifetime broadly defined–only IED is the excluded category.

Significant at P < .05, 2-sided test, controlling for age, sex, race, region, urbanicity, parent educational level, number of biological parents, birth order, and number of siblings.

Temporal sequencing of onset of IED vs comorbid disorders was examined by calculating the proportion of lifetime comorbid cases in which AAO of IED was earlier, later, or within the same year as that of the comorbid disorder (detailed results available on request). First onset of IED occurred before onset of comorbid substance disorders in nearly all cases (92.0%–92.6%), before comorbid distress disorders in about half the cases (48.8%–55.6% for major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), and before comorbid panic disorder in 45.6% of the cases. In contrast, most cases of comorbid phobias and separation anxiety disorder had first onset before IED (58.7%–91.9%).

TREATMENT

Although more than one-third (37.8%) of respondents with 12-month IED received treatment for emotional problems in the year of the interview, only 17.1% of those with this treatment were treated specifically for anger (6.5% of all 12-month cases) (Table 5). The vast majority of the latter respondents received treatment in the mental health specialty sector (6.0% of all 12-month cases).

Table 5.

12-Month Treatment of DSM-IV/CIDI IED Among 6483 Adolescents in the NCS-A

| Characteristic | % (SE)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 12-mo Treatmenta | 12-mo Treatment and Received Treatment for IED in the Past 12 mob | Patients Who Received Treatment for IED Among Those Who Had Received 12-mo Treatmentc | |

| Mental health specialty | 16.6 (3.3) | 6.0 (1.8) | 36.0 (10.1) |

| General medical | 9.3 (3.3) | 0.3 (0.2) | 3.5 (2.2) |

| School medication | 22.6 (4.2) | 4.6 (1.8) | 20.4 (7.6) |

| Any health care | 24.3 (4.0) | 6.1 (1.8) | 25.1 (6.6) |

| Human services | 10.2 (2.9) | 0.2 (0.1) | 1.6 (1.1) |

| Complementary/alternative medicine | 2.9 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.0) | 51.8 (20.7) |

| Juvenile justice | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Any treatment | 37.8 (3.6) | 6.5 (1.9) | 17.1 (5.0) |

Abbreviations: CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; IED, intermittent explosive disorder; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.

Proportion of 12-mo cases that received treatment in the past year from the specified treatment sector.

Proportion of 12-mo cases that received treatment in the past year from the specified treatment sector and received treatment for IED.

Ratio of the first 2 columns, with the first column serving as the denominator.

COMMENT

The results are limited in several ways. First, although the CIDI assessment of IED has good face validity, diagnoses were not validated against independent clinical assessments and might be less sensitive than clinical assessments to distinctions between IED and other disorders involving impulsive aggression. However, we adopted stringent criteria that excluded anger attacks in the context of depression, substance abuse, and disorders characterized by aggression to ensure that IED was not diagnosed among respondents whose symptoms could be better accounted for by another DSM-IV disorder assessed in the survey. These exclusions might have resulted in conservative estimates of IED prevalence. Second, estimates of lifetime prevalence, AAO, and course are based on retrospective reports. Methods shown experimentally to improve the accuracy of retrospective reports were used to address this problem,25 but recall bias nevertheless is a concern. Third, assessments were based on adolescent-only reports, although we would expect this limitation to lead to an underestimation rather than overestimation of prevalence. Fourth, prevalence estimates were based on operational definitions that differ somewhat from other proposed criteria.26,27

Within the context of these limitations, the results constitute what we believe to be the first national data on prevalence and correlates of adolescent IED. Anger attacks were found to be common (63.3% of the sample), but nearly half of participants with any anger attacks had experienced only 1 to 2 and another one-third only had attacks proportional in response to provoking circumstances or not out of control. Most attacks occurred in the approximately one-fifth of other adolescents with anger attacks, including 7.8% of the sample with IED (with a mean number of 17.6 lifetime attacks, representing 17.9% of all attacks in the sample) and 6.2% of the sample with diagnostic exclusions (with a mean number of 47 lifetime attacks, representing 38.0% of all attacks in the sample). The higher mean among participants with other disorders presumably reflects anger attacks often being prodrome, residual, and/or severity markers of these disorders. Only about 12% of adolescents with anger attacks met the criteria for IED. As a point of comparison, approximately one-fourth of people with panic attacks meet criteria for panic disorder.28

The NCS-A IED prevalence estimates (5.3%–7.8% lifetime and 1.7%–6.2% 12-month prevalence) are similar to NCS-R estimates for adults (5.4%–7.3% lifetime and 2.7%–3.9% 12-month prevalence)4 despite IED being defined much more narrowly in the adolescent sample by excluding individuals with disruptive behavior disorders. This exclusion was not applied for adults because most lifetime behavior disorders were resolved among adults. Based on NCS-R results4 that 44.9% of adults with IED had a history of child-adolescent ADHD, ODD, or CD that remitted even though IED did not remit, we anticipated that a meaningful number of the adolescents with anger attacks excluded from a diagnosis of IED in the NCS-A because of comorbid behavior disorders would be classified as having IED if they were followed up into adulthood.

The NCS-A results confirm retrospective NCS-R results that IED begins early in life, exhibits a persistent course, co-occurs with a wide range of other disorders, and is associated with significant impairment and low treatment.4 The significant property damage and injury associated with IED underscores the public health significance of the disorder and suggests that the high estimated prevalence of IED reflects a true mental disorder as opposed to overdiagnosis of developmentally normative behavior.

The early AAO of IED is also important with regard to comorbidity because it shows that IED is temporally primary to many of the comorbid substance abuse and distress disorders.29 Intermittent explosive disorder might be a risk factor or a risk marker for these temporally secondary comorbid disorders.30 We are unaware of any systematic prospective research on the possibility that IED is a predictor of secondary mental disorders. The fact that so few adolescents with IED obtain treatment for anger becomes even more important in light of the possibility that IED is a causal risk factor for secondary disorders; this means that an opportunity is being missed to intervene at a time when it might be possible to prevent the onset of later disorders. An as-yet unanswered question raised by this possibility is whether successful early detection and treatment of IED would prevent later disorders. Given the early AAO distribution of IED, early detection and intervention would most reasonably take place in schools and might be addressed as an addition to school-based violence prevention programs.31,32

The only sociodemographic correlates of lifetime IED that we were able to document are related to family structure and size. Adolescents who do not live with both biological parents and who have more siblings have elevated odds of IED. Not living with both biological parents is the most consistent sociodemographic correlate of mental disorders in the NCS-A and is likely to be a nonspecific risk marker for psychopathology, whereas having more siblings is associated in the NCS-A specifically with behavior disorders, including not only IED but also CD.10 Although the prevalence of anger attacks is considerably higher among boys than girls, the prevalence of lifetime IED does not differ by sex.

Several important issues regarding IED diagnosis remain unresolved. The first relates to the distinction between broad and narrow definitions of IED. The most severe form of IED in our study (narrowly defined) was more persistent and associated with greater functional impairment than was the less severe form (broadly defined). This finding points to the importance of identifying the optimal diagnostic threshold for required frequency and clustering of anger attacks.

A second issue concerns the types of aggressive behavior that should be included in criterion A for a diagnosis of IED. A broader set of diagnostic criteria for IED has been proposed that includes recurrent aggressive outbursts that do not include threatened or actual violence or destruction of property (eg, verbal aggression against others, such as insults or arguments out of proportion to provocation).26,27 Although this issue was not included in the NCS-A assessment, the one study33 that examined it found that such individuals have levels of anger, hostility, aggressive responses to provocation, and functional impairment equivalent to those of individuals who meet full DSM-IV criteria for having IED. Because verbal aggression in the absence of threats, physical violence, or property destruction is significantly impairing and has been shown34 to respond to psychopharmacologic treatment, a case could be made for including these behaviors in a revision of the diagnostic criteria for IED, although the high prevalence of verbal aggression would make it important to be precise in characterizing the persistence and severity required to qualify for a diagnosis. An analysis carried out in a subsample of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study3 estimated that the prevalence of IED would be approximately 25% higher if verbal aggression were included in the diagnosis.

A third issue concerns whether IED is sufficiently distinct from other mental disorders to be considered a disorder rather than a prodrome, residual, or severity marker of other disorders.2,4,27,35 Aggressive behavior occurs in a wide range of mental disorders other than IED36,37 and is a core feature of ODD, CD, and antisocial personality disorder.21,22 In combination with negative mood, aggressive behavior is the focus of a proposed DSM-5 diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD).38 An evaluation of the overlap between DSM-IV IED and the proposed DSM-5 DMDD is beyond the scope of the NCS-A, since the survey did not assess several of the proposed diagnostic criteria of DMDD. It is relevant in this regard, though, that we found a high prevalence of DSM-IV IED, even after applying stringent exclusions for concomitant disorders. Moreover, there is at least some evidence39,40 that IED is distinguishable from nonpathologic aggression, antisocial and borderline personality disorders, and depressive disorders. In addition, the one published study41 of family aggregation of IED found high intergenerational continuity of the disorder independent of comorbid conditions. Together, these findings suggest that IED might be distinct not only from the disorders used as exclusions in the current study but also from DMDD, although resolution must await a study directly addressing this issue.

Putting aside the issue of overlap with DMDD, the NCS-A results strongly suggest that IED is a commonly occurring disorder among US adolescents and has high persistence and severity. However, the data also show that IED is undertreated, both in that a high proportion of youth with IED do not receive treatment for any emotional problems and, in those who do receive treatment, the focus for many is a disorder other than IED. Intermittent explosive disorder is also understudied, as indicated by the fact that the number of PubMed research reports dealing with panic attacks is roughly 60 times the number dealing with anger attacks even though the lifetime prevalence of IED is considerably higher than the prevalence of panic disorder. Given the substantial consequences of IED for individuals and society, research is sorely needed to resolve diagnostic disagreements, uncover risk and protective factors, and develop strategies for screening, early detection, and effective treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The NCS-A is supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants U01-MH60220 and R01-MH66627, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, grant 044780 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the John W. Alden Trust. Preparation of this manuscript was also supported by NIMH grants K01-MH092526 (Dr McLaughlin) and K01-MH085710 (Dr Green). The World Mental Health (WMH) Data Coordination Centres have received support from NIMH grants R01-MH070884, R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01-MH077883; NIDA grant R01-DA016558; the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health grant R03-TW006481; the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; the Pfizer Foundation; and the Pan American Health Organization. The WMH Data Coordination Centres have also received unrestricted educational grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, sanofiaventis, and Wyeth.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors had full access to all the data in the study. Dr Kessler takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US government.

Additional Contributions: The staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres assisted with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Kessler has been a consultant for Analysis Group, Inc, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerner-Galt Associates, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline Inc, HealthCore Inc, Health Dialog, Integrated Benefits Institute, John Snow Inc, Kaiser Permanente, Matria Inc, Mensante, Merck & Co, Inc, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc, Primary Care Network, Research Triangle Institute, sanofiaventis Groupe, Shire US Inc, SRA International Inc, Takeda Global Research & Development, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Appliance Computing II, Eli Lilly & Company, Mindsite, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Plus One Health Management, and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has had research support for epidemiologic studies from Analysis Group, Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, EPI-Q, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc, sanofiaventis Groupe, and Shire US Inc.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coccaro EF, Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Prevalence and features of intermittent explosive disorder in a clinical setting. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1221–1227. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coccaro EF, Schmidt CA, Samuels JF, Nestadt G. Lifetime and 1-month prevalence rates of intermittent explosive disorder in a community sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(6):820–824. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Coccaro EF, Fava M, Jaeger S, Jin R, Walters EE. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):669–678. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchard-Fields F, Coats AH. The experience of anger and sadness in everyday problems impacts age differences in emotion regulation. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(6):1547–1556. doi: 10.1037/a0013915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant JE, Williams KA, Potenza MN. Impulse-control disorders in adolescent psychiatric inpatients: co-occurring disorders and sex differences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1584–1592. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell BE, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A): II: overview and design. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):380–385. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181999705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell BE, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(2):69–83. doi: 10.1002/mpr.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, He J-P, Koretz D, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Pine DS, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Psychol Med. 2012:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):78–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braaten EB, Biederman J, DiMauro A, Mick E, Monuteaux MC, Muehl K, Faraone SV. Methodological complexities in the diagnosis of major depression in youth: an analysis of mother and youth self-reports. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(4):395–407. doi: 10.1089/104454601317261573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Guyer M, He Y, Jin R, Kaufman J, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky A. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A), III: concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK, Jensen PS, Fisher P, Bird HR, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Lichtman JH, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Rae DS. Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):878–888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McElroy SL. Recognition and treatment of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 15):12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McElroy SL, Soutullo CA, Beckman DA, Taylor P, Jr, Keck PE., Jr DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder: a report of 27 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 (4):203–211. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlis RH, Smoller JW, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS. The prevalence and clinical correlates of anger attacks during depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1–3):291–295. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eronen M, Hakola P, Tiihonen J. Mental disorders and homicidal behavior in Finland. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):497–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060039005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N, Poduska J, Kellam S. Modeling growth in boys’ aggressive behavior across elementary school: links to later criminal involvement, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Dev Psychol. 2003;39(6):1020–1035. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halli SS, Rao KV, Halli SS. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. New York, NY: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving accuracy of major depression age-of-onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999;8(1):39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2(1):67–71. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ, Berman ME, Lish JD. Intermittent explosive disorder–revised: development, reliability, and validity of research criteria. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(6):368–376. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Walters EE. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):415–424. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder. In: Coccaro EF, editor. Aggression: Psychiatric Treatment and Assessment. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2003. pp. 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY Aban Aya Investigators. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer G, Roberto AJ, Boster FJ, Roberto HL. Assessing the Get Real about Violence curriculum: process and outcome evaluation results and implications. Health Commun. 2004;16(4):451–474. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1604_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCloskey MS, Lee R, Berman ME, Noblett KL, Coccaro EF. The relationship between impulsive verbal aggression and intermittent explosive disorder. Aggress Behav. 2008;34(1):51–60. doi: 10.1002/ab.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coccaro EF, Lee RJ, Kavoussi RJ. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in patients with intermittent explosive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):653–662. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCloskey MS, Berman ME, Noblett KL, Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder—integrated research diagnostic criteria: convergent and discriminant validity. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(3):231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berman ME, Fallon AE, Coccaro EF. The relationship between personality psychopathology and aggressive behavior in research volunteers. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(4):651–658. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swanson JW, Holzer CE, III, Ganju VK, Jono RT. Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(7):761–770. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, Dickstein DP, Guyer AE, Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(9):991–997. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed AO, Green BA, McCloskey MS, Berman ME. Latent structure of intermittent explosive disorder in an epidemiological sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(10):663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnett J. Reckless behavior in adolescence: a developmental perspective. Dev Rev. 1992;12(4):339–373. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coccaro EF. A family history study of intermittent explosive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(15):1101–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]