Abstract

Background

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common and have been associated with the subsequent diagnosis of prostate cancer (PCa) in population cohorts.

Objective

To determine whether the association between LUTS and PCa is due to the intensity of PCa testing after LUTS diagnosis.

Design, setting, and participants

We prospectively followed a representative, population-based cohort of 1922 men, aged 40–79 yr, from 1990 until 2010 with interviews, questionnaires, and abstracting of medical records for prostate outcomes. Men were excluded if they had a previous prostate biopsy or PCa diagnosis. Self-reported LUTS was defined as an American Urological Association symptom index score >7 (n = 621). Men treated for LUTS (n = 168) were identified from review of medical records and/or self report. Median follow-up was 11.8 yr (interquartile range: 10.7–12.3).

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Associations between self-reported LUTS, or treatment for LUTS, and risk of subsequent prostate biopsy and PCa were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results and limitations

Fifty-five percent of eligible men enrolled in the study. Men treated for LUTS were more likely to undergo a prostate biopsy (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–3.3). Men younger than 65 yr who were treated for LUTS were more likely to be diagnosed with PCa (HR: 2.3, 95% CI, 1.5–3.5), while men aged >65 yr were not (HR: 0.89, 95% CI, 0.35–1.9). Men with self-reported LUTS were not more likely to be biopsied or diagnosed with PCa. Neither definition of LUTS was associated with subsequent intermediate to high-risk cancer. The study is limited by lack of histologic or prostate-specific antigen level data for the cohort.

Conclusions

These results indicate that a possible cause of the association between LUTS and PCa is increased diagnostic intensity among men whose LUTS come to the attention of physicians. Increased symptoms themselves were not associated with intensity of testing or diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common solid malignancy among men in the United States [1], and one of the most common in the world [2]. The incidence increases in an age-dependent manner and autopsy studies suggest that at some point, nearly every man may eventually develop PCa [3]. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are also common as men age and are present in >50% of men aged >60 yr and nearly 100% of men aged ≥90 yr [4, 5]. LUTS are generally attributed to benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), and though BPH can cause LUTS, LUTS can occur in the absence of BPH. Furthermore, both LUTS [6] and BPH [7] have been associated with the subsequent risk of PCa. These three related disease processes (LUTS, BPH, and PCa) share much more in common: They increase in an age-dependent manner [4, 8], they all tend to worsen through a hormone-dependent mechanism [9, 10], inflammation may play a role in the development of all three processes [11, 12], and they can be treated with antihormone medications [13–15]. These similarities, along with epidemiologic data from large populations suggesting a possible link, have fueled a debate since the 1940s as to whether the association between BPH and/or LUTS and PCa is causative [6, 7].

Despite these similarities, BPH and or LUTS have not been considered traditional risk factors for the subsequent development of PCa [5]. This may be due, in part, to evidence from a recent publication from the placebo arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT), which suggested there was no association between LUTS and PCa [16]. However, a recent, large, population-based study from Europe found a rather marked association between LUTS and the subsequent risk of PCa with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 2.2 to 4.5 [6]. Of note, these estimates of relative risk (RR) are as high or higher than more traditional risk factors such as family history (RR: 2–4), prostatitis (RR: 1.5), race (African American vs white, RR: 1.3), sexually transmitted diseases (RR: 1.5), and obesity (RR: 1.05) [17]. Unfortunately, the European study did not have a standardized measurement of LUTS and was unable to evaluate whether the association between clinical LUTS and PCa incidence was merely detection bias. In other words, were the men who were diagnosed with LUTS more likely to be diagnosed with PCa because of more frequent physician contact, leading to more frequent prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, digital rectal exams (DRE), and prostate biopsies, resulting in higher rates of cancer diagnosis [18, 19]? If there were a true biologic association between LUTS and PCa, we might expect to observe men with symptomatic LUTS developing PCa at consistent rates regardless of whether they obtain treatment for their LUTS or not. To address the shortcomings of the previous studies, we evaluated the association of LUTS with subsequent risk for prostate biopsy and PCa diagnosis in a population-based cohort of men in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA.

2. Methods

2.1. Study cohort and follow-up

The study population consisted of 1922 men aged 40–79 yr who were living in Olmsted County and enrolled in a prospective cohort study entitled Natural History of Prostatism: The Olmsted County Study (US National Institutes of Health grant number DK058859). The entire cohort has been described previously [20].

Beginning in 1990, 3874 randomly selected men between the ages of 40 and 79 yr and living in Olmsted County were invited to participate; 2115 (55%) of eligible subjects enrolled at baseline and completed biennial questionnaires about overall health status, urinary symptoms (including an American Urological Association symptom index [AUASI]), and sexual function. Men in the first few years of the study who died or were lost to follow-up were replaced during rounds 2 and 3 (in 1992 and 1994), resulting in a total of 2447 study participants. The study population was then maintained as a closed cohort and followed biennially. A random subsample of these men (n = 634) was then selected as a clinic cohort, with 87% of invited men electing to participate in a biennial physical exam including a DRE, PSA screening, and a transrectal ultrasound of the prostate. Men not included in the clinic cohort completed questionnaires only and were free to undergo PSA screening, DRE, and transrectal ultrasound at the discretion of their own physicians. Men were followed until January 1, 1997, to allow for the accumulation of a sufficient number of men undergoing either surgical (n = 29) or medical (n = 139) LUTS treatment, as a comparison cohort. Sensitivity analyses were performed using several time points (1995, 1999, and 2001) and effects were similar (data not shown). The year 1997 was chosen as the end point for follow-up because it allowed a sufficient number of men in the cohort of those treated for LUTS with adequate follow-up for evaluation of the events of interest (ie, prostate biopsy and PCa). Men with a benign prostate biopsy (n = 221), diagnosis of PCa (n = 93), or those who chose not to continue in the study prior to January 1, 1997 (n = 211), were excluded, leaving 1922 men. All men treated for LUTS prior to this date were included in a cohort (n = 168, 8.4%). The median year of treatment was 1994 (interquartile range [IQR]: 1992–1995). In addition, a cohort of men with self-reported moderate to severe LUTS was identified by using an AUASI score >7 prior to January 1, 1997 (n = 621, 33%). Institutional review was obtained from the Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center.

The community medical records of all the men in the study were abstracted to obtain information on PCa diagnosis, prostate biopsy, death, and cause of death. Cause of death was also verified using the death certificate.

Differences between the cohorts were analyzed by Pearson chi-square or Wilcoxon log-rank tests as appropriate. Unfortunately, we did not have complete PSA testing results for the entire population as a measure of diagnostic intensity; however, we did have prostate biopsy information during follow-up and this was used as a proxy for diagnostic intensity. Risk of subsequent biopsy or cancer diagnosis was calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves, the log-rank test, and unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional HRs. All analyses were performed using JMP v.9.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) All tests of statistical significance were two-sided with alpha <0.05.

3. Results

The characteristics of the population stratified according to LUTS treatment status and normal/moderate/severe LUTS are presented in Table 1. The median AUASI of those receiving treatment was comparable to the median score of men with self-reported moderate to severe LUTS. Length of follow-up, family history of PCa, and participation in the clinic cohort were similar between the groups. However, those with self-reported LUTS and those receiving LUTS treatment were older on average than population controls.

Table 1.

Comparison of the population stratified by two lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) definitions: men with LUTS who were treated and men with self-reported moderate to severe LUTS by American Urological Association Symptom Index score >7

| Men with treated LUTS: characteristics at baseline |

Men with LUTS treatment (n = 168) |

Men without LUTS treatment (n = 1754) |

p value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry, yr, median (IQR) | 66.2 (60.3–72.3) | 55.4 (49.5–63.9) | <0.0001 |

| Follow-up, yr, median (IQR) | 10.8 (7.4–11.7) | 11.1 (8.8–11.8) | 0.09 |

| Family history of PCa, no. (%) | 20 (12) | 153 (9) | 0.17 |

| Baseline AUA symptom score, median (IQR) ** | 10 (5–16) | 5 (2–9) | <0.0001 |

| Subsequent prostate biopsy, no. (%) | 50 (30) | 239 (14) | *** |

| Subsequent PCa, no. (%) † | 19 (11) | 126 (7) | †† |

| Low-risk cancer ‡, no. (%) | 12 (7.1) | 78 (4.4) | 0.11 |

| Intermediate/high-risk cancer ‡‡, no. (%) | 6 (3.6) | 41 (2.3) | |

| Clinic cohort, no. (%) | 48 (29) | 444 (25) | 0.4 |

| Baseline PSA level for this subset of 492 patients, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 1.4 (1.0–2.75) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Men with self-reported moderate to severe LUTS by AUASI score >7: characteristics at baseline | Self-reported moderate/severe LUTS £ (n = 621) | No self-reported moderate/severe LUTS £ (n = 1218) | p value |

| Age at entry, yr, median (IQR) | 54.2 (51.8–69.2) | 48.8 (49.6–63.4) | <0.0001 |

| Follow-up, yr, median (IQR) | 11.7 (10.5–12.2) | 11.8 (10.8–12.4) | 0.04 |

| Family history of PCa, no. (%) | 55 (8.9) | 107 (8.8) | 0.9 |

| Baseline AUA symptom score, median (IQR) ** | 11 (9–15) | 3 (2–5) | <0.0001 |

| Subsequent prostate biopsy, no. (%) | 106 (17.1) | 174 (14.3) | *** |

| Subsequent prostate cancer, no. (%)§ | 43 (6.9) | 94 (7.7) | †† |

| Low-risk cancer ‡, no. (%) | 30 (4.8) | 55 (4.5) | 0.8 |

| Intermediate/high-risk cancer ‡‡, no. (%) | 11 (1.8) | 33 (2.7) | |

| Clinic cohort, no. (%) | 171 (27.5) | 304 (25) | 0.2 |

| Baseline PSA level for this subset of 492 patients, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.15 |

IQR = interquartile range; PCa = prostate cancer; AUA = American Urological Association; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; AUASI = AUA symptom index.

Pearson chi-square test, family history, clinic cohort, prostate cancer risk group, Wilcoxon log-rank test, age at entry, median follow-up, and AUASI. Time-to-event variables were analyzed separately in Table 1.2 and 1.3, only raw event data are presented here.

Eighty-three men did not complete AUASI.

See Table 2.

Eight men missing pathology.

See Table 3.

Gleason score <7, PSA >10 ng/ml.

Gleason score >6, PSA ≥ 10 ng/ml.

Moderate/severe LUTS defined at AUA symptom score >7.

Ten men with missing pathology.

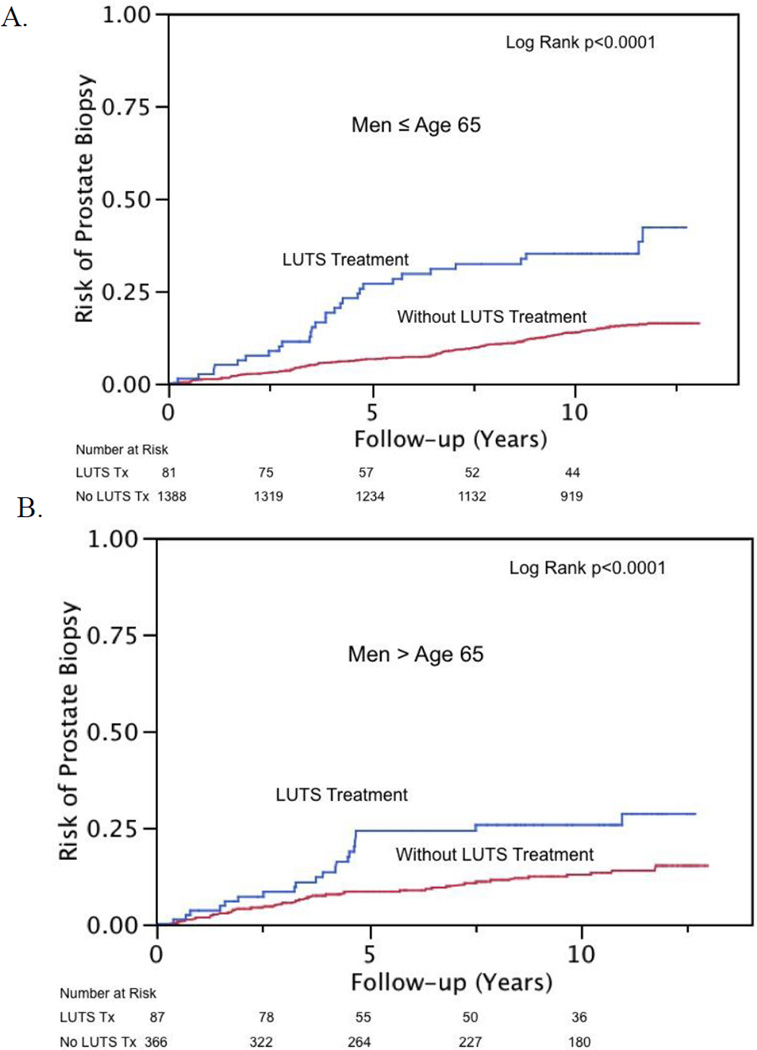

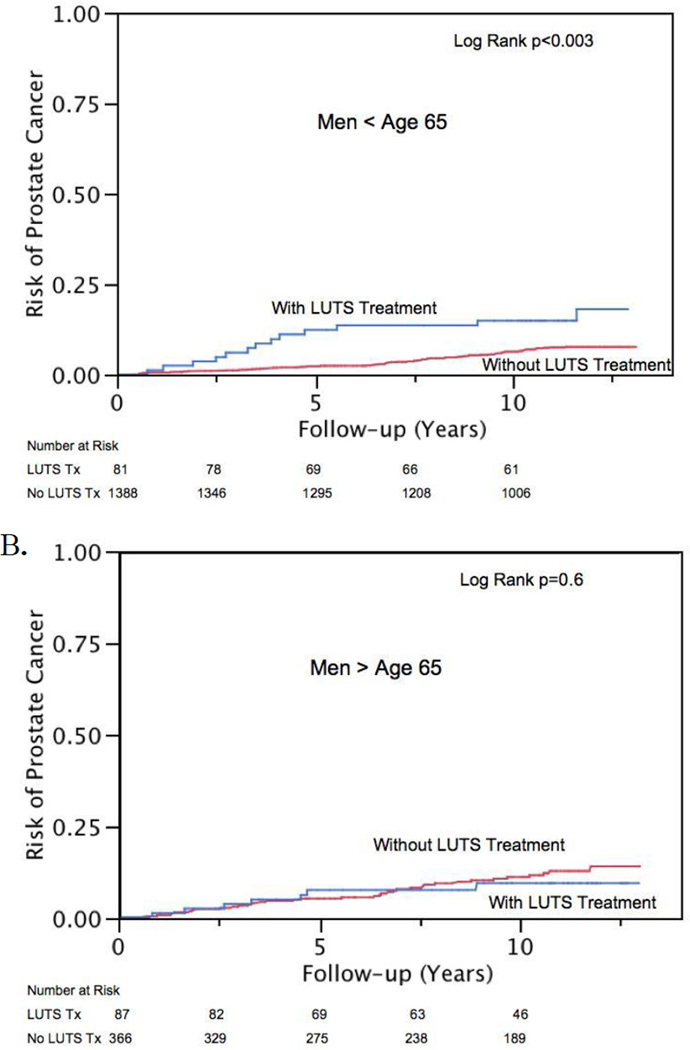

Kaplan-Meier estimates of risk of biopsy and PCa diagnosis are presented in Figure 1 and 2, respectively. Treated LUTS interacted with age and the association of subsequent PCa diagnosis (interaction term p = 0.03). Therefore, analyses were stratified at age 65 yr for men with treated LUTS for the outcome of PCa. Treated LUTS did not interact with age and subsequent prostate biopsy (interaction term p = 0.053), nor was such interaction observed in patients with self-reported moderate to severe LUTS and subsequent biopsy or PCa diagnosis (interaction term p = 0.2 and 0.7, respectively). Proportional hazard models, both unadjusted and adjusted, are displayed in Table 2 and 3. Men treated for LUTS were more likely to be biopsied (HR: 2.4; 95% CI, 1.7–3.3) regardless of age. However, younger men (<65 yr) were also more likely to be diagnosed with cancer (HR: 2.4; 95% CI, 1.2–4.2) than men of similar age who were not undergoing treatment. Most of the excess risk appears to be due to low-risk cancers (HR: 2.3; 95% CI, 1.0–4.8). There were only 44 intermediate- or high-risk cancer events and an interaction was not noted with age and LUTS treatment (p = 0.15). On multivariate Cox models adjusting for age, AUA symptom score, and family history, men treated for LUTS were no more likely to be diagnosed with intermediate- or high-risk cancers than men without (HR: 1.19; 95% CI, 0.43–2.8). Most of this increased risk appears to occur in the first 5–8 yr after treatment for LUTS (Fig. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Risk of subsequent prostate biopsy in men undergoing treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) versus men not treated for LUTS stratified by age (a) ≤65 yr and (b) >65 yr.

Fig. 2.

Risk of subsequent prostate cancer diagnosis by lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS) treatment in men aged (a) ≤65 yr and (b) >65 yr.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of risk of prostate biopsy

| Characteristics at baseline | HR (95% CI), unadjusted |

HR (95% CI), adjusted * |

|---|---|---|

| Family history | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) |

| Treatment for LUTS | 2.4 (1.3–4.2) | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) |

| Moderate to severe LUTS (AUASI ≥7) | 1.32 (1.0–1.8) | NA |

| AUASI as continuous variable (HR for each unit increase) | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

| Participant in the clinic cohort | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; AUASI = American Urological Association symptom index; NA = not applicable.

Adjusted model included age, family history, treatment for LUTS, and AUASI and clinic-cohort status.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of risk of prostate cancer diagnosis stratified by age

| Characteristics at baseline | HR (95% CI), unadjusted |

HR (95% CI), adjusted * |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Men ≤65 yr | Family history | 2.7 (1.6–4.3) | 2.6 (1.5–4.4) |

| Treatment for LUTS | 2.4 (1.3–4.2) | 2.4 (1.2–4.2) | |

| Moderate to severe LUTS (AUASI ≥7) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | n/a | |

| AUASI as continuous variable (HR for each unit increase) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | |

| Participant in the clinic cohort | 1.2 (0.77–1.87) | 1.2 (0.74–1.9) | |

| Men >65 yr | Family history | 2.6 (1.2–5.1) | 2.2 (0.94–4.9) |

| Treatment for LUTS | 0.78 (0.32–1.7) | 0.89 (0.35–1.9) | |

| Moderate to severe LUTS (AUASI ≥7) | 0.74 (0.38–1.4) | n/a | |

| AUASI as continuous variable (HR for each unit increase) | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) | |

| Participant in the clinic cohort | 1.68 (0.88–3.1) | 1.8 (0.95–3.5) |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; AUASI = American Urological Association symptom index; n/a = not applicable.

Adjusted model included family history, treatment for LUTS, and AUASI and clinic cohort status.

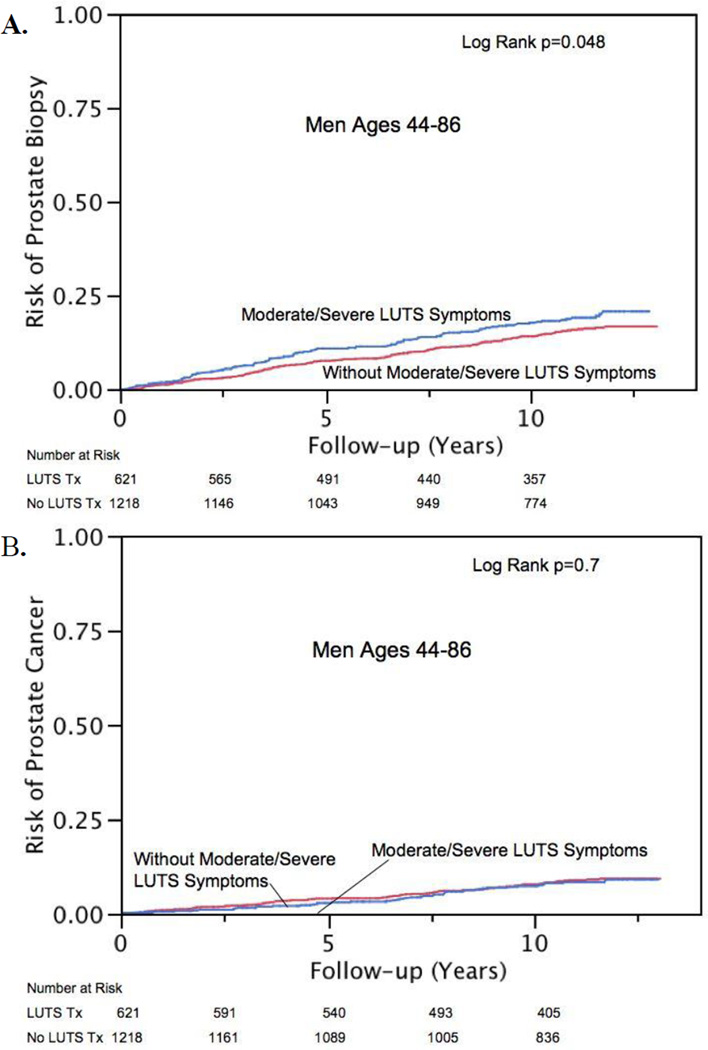

Univariate Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrating the subsequent risk of prostate biopsy and cancer diagnosis are displayed in Figure 3, stratified by self-reported LUTS. Men with moderate to severe LUTS were no more likely to be biopsied or diagnosed with PCa after adjusting for age, family history, and participation in the clinic cohort (HR: 1.2; 95% CI, 0.93–1.5 and HR: 0.80; 95% CI, 0.54–1.1, respectively). Furthermore, when AUASI was evaluated as a linear variable, it was not associated with either the subsequent risk of biopsy or PCa (Table 2 and 3).

Fig. 3.

Risk of (a) subsequent biopsy or (b) prostate cancer diagnosis among men with and without self-reported moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

Men treated surgically for LUTS were no more likely to be biopsied or develop cancer when controlling for age, family history, AUASI, and participation in the clinic cohort (HR: 0.61; 95% CI, 0.15–1.6 and HR: 0.92; 95% CI, 0.23–2.6, respectively). However, younger men (<65 yr) treated with medical therapy for their LUTS were more likely to be biopsied and diagnosed with PCa (HR: 3.2; 95% CI, 2.1–4.6 and HR: 2.7; 95% CI, 1.6–4.6, respectively) on adjusted analyses.

4. Discussion

Researchers have long wondered if there is a biologic association between BPH and/or LUTS and PCa [7, 21, 22]. Autopsy studies have found evidence of BPH in conjunction with PCa 83% of the time [23], and while BHP and LUTS are not synonymous, a recent, large, population-based study from Europe also found a rather marked association with LUTS and the subsequent risk of PCa, with HRs ranging from 2.2 to 4.5 [6]. Unfortunately, this population-based study, though impressive in its size (3 million people), was unable to assess whether this association was merely due to detection bias, and goes against another recent publication from the PCPT [16]. The placebo arm of PCPT used multiple definitions of LUTS, including medical treatment, surgical treatment, and a standardized questionnaire, and found that no definition of LUTS was associated with cancer. But this study is flawed in that the stringent exclusion criteria at study entry may not be representative of the general population [24]. Furthermore, all participants were evaluated uniformly with annual PSA level tests, DREs, and end-of-study biopsies, effectively eliminating the potential to measure a detection bias.

In our study, we had a standardized measurement of LUTS in 96% of our population and known prostate biopsy rates. This allowed us to compare the association between LUTS and subsequent cancer testing and diagnosis. In this population, there was no association between moderate to severe symptoms and subsequent PCa testing and diagnosis. However, there was a significant association between treated LUTS and PCa testing and diagnosis. We observed >2-fold increase in risk for biopsy in the first 5–8 yr after being treated for LUTS and a similar increased risk for cancer diagnosis in men treated for LUTS (HR: 2.4). However, this increased risk for cancer was only apparent in the men treated for LUTS prior to age 65 yr (Table 3). These findings argue against a biologically causative relationship between LUTS and PCa, and point toward detection bias. It is possible that LUTS treatment could result in increased physician contact. Increased physician contact could, in turn, result in a higher likelihood of testing for and diagnosis of PCa. Our findings tend to bridge the gap between the results of population studies [6] and the recent results published from the placebo arm of the PCPT [16].

Our data are unable to address other confounding variables or biologic differences between men with moderate to severe LUTS who seek treatment versus those who do not. In our study, these two cohorts had comparable baseline AUASI scores (Table 1), but had very different risks of cancer (Table 3). We note that the types of PCa diagnosed were similar between the groups, with about 70% of men presenting with low-risk cancer regardless of cohort (Table 1). These results suggest that men treated for LUTS who go on to be diagnosed with PCa do not appear to present with lower-risk PCa.

Our hypothesis for the reason for the higher PCa risk in younger men with treated LUTS may be summarized in the following scenario. A younger man seeking treatment for his LUTS will interact with physicians, have a PSA screening, and a DRE performed more often than a man of the same age not seeking treatment for his LUTS. This, in turn, results in a higher biopsy rate and the diagnosing of cancers that may not otherwise have been diagnosed. Although there was a higher risk of undergoing a biopsy in men treated for LUTS who were aged >65 yr, we did not observe an increased risk for PCa. The reason for this is unclear. It may be there is no association in older men, or conversely, in an older man the diagnosis of LUTS may mask (or explain) a potentially larger prostate or higher PSA level. In other words, a biopsy in a larger gland may fail to find PCa (as observed in the PCPT), or the physician may be less willing to biopsy because the elevated PSA level in an older man with LUTS is likely due to BPH. Furthermore, if men have a life expectancy of <10 yr, AUA guidelines recommend against screening for PCa, and therefore fewer cancers will likely be diagnosed in older men with LUTS because life expectancy is shorter.

Though our data cannot prove the aforementioned theory, they are compatible with this explanation. However, another plausible explanation is that bothersome LUTS lead to the detection of clinically significant PCa. However, if clinically significant PCa caused LUTS that led men to seek treatment, and then they were fortuitously found to have early PCa, we may expect that intermediate- to high-risk cancers, along with the low-risk cancers, would be associated with subsequent LUTS. We observed, however, that the HR for subsequent low-risk cancer was 2.3 compared to 1.19 for intermediate- to high-risk cancer. It remains unclear whether diagnosing these low-risk cancers may lead to some survival benefit down the road, since there was only one cancer-related death during the study period.

This study is limited by size, lack of PSA/DRE test results for the entire cohort, lack of tabulation of doctor’s visits, lack of bother scores, and poorly defined indications for biopsy. Furthermore, we had no data on BPH and were only able to measure the association between LUTS and PCa. We also were unable to measure whether medical treatment of LUTS causes pathophysiologic changes in the prostate that lead to cancer. Nevertheless, this study has merit in its population-based nature, the long-term follow-up, and the standardized measurement of urinary symptoms. It bridges the gap between previous population-based studies and the subset analyses of a clinical trial.

5. Conclusions

These results suggest that the association between LUTS and PCa observed in population-based studies may be due to increased diagnostic intensity among men whose LUTS come to the attention of physicians. We were unable to find any association between the symptoms themselves and PCa.

Take-home message.

The association between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and prostate cancer observed in population-based studies may be due to increased diagnostic intensity among men whose LUTS come to the attention of physicians rather than an underlying, shared biologic etiology or causative mechanism.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: Rochester Epidemiology Project Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This project was supported by research grants from the Public Health Service, NIH (DK58859, AR30582, and 1UL1 RR024150-01), and Merck Research Laboratories.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: Christopher J. Weight had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Weight, Kim, St. Sauver, Jacobson.

Acquisition of data: Jacobson, McGree, St. Sauver.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Weight, Jacobson, St. Sauver, McGree.

Drafting of the manuscript: Weight.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Weight, Boorjian, Karnes, Thompson, Leibovich, Kim, St. Sauver.

Statistical analysis: Weight, McGree, Jacobson, St. Sauver.

Obtaining funding: St. Sauver.

Administrative, technical, or material support: St. Sauver.

Supervision: St. Sauver, Karnes.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Christopher J. Weight certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/ affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int JCancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell IJ, Bock CH, Ruterbusch JJ, Sakr W. Evidence supports a faster growth rate and/or earlier transformation to clinically significant prostate cancer in black than in white american men, and influences racial progression and mortality disparity. J Urol. 2010;183:1792–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, et al. American Urological Association clinical practice guidelines. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) [Accessed February 20, 2012];American Urological Association Web site. 2010 http://www.auanet.org/content/clinical-practice-guidelines/clinical-guidelines/main-reports/bph-management/authors.pdf.

- 5.Bostwick DG, Burke HB, Djakiew D, et al. Human prostate cancer risk factors. Cancer. 2004;101(Suppl):2371–2490. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orsted DD, Bojesen SE, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Association of clinical benign prostate hyperplasia with prostate cancer incidence and mortality revisited: a nationwide cohort study of 3,009,258 men. Eur Urol. 2011;60:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopp RP, Freedland SJ, Parsons JK. Associations of benign prostatic hyperplasia with prostate cancer: the debate continues. Eur Urol. 2011;60:699–700. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.005. discussion 701–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alcaraz A, Hammerer P, Tubaro A, Schröder FH, Castro R. Is there evidence of a relationship between benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer? Findings of a literature review. Eur Urol. 2009;55:864–875. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson C, III, Rittmaster R. The role of dihydrotestosterone in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2003;61(Suppl 1):2–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tindall DJ, Rittmaster RS. The rationale for inhibiting 5α-reductase isoenzymes in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008;179:1235–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels NA, Ewing SK, Zmuda JM, Wilt TJ, Bauer DC. Correlates and prevalence of prostatitis in a large community-based cohort of older men. Urology. 2005;66:964–970. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB. Prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:366–381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802263380901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C. Role of androgen in prostate growth and regression: stromal-epithelial interaction. Prostate Suppl. 1996;6:52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenk JM, Kristal AR, Arnold KB, et al. Association of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1419–1428. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abouassaly R, Thompson IM, Jr, Platz EA, Klein EA. In: Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Patin AW, Peters CA, editors. vol 3. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011. pp. 2708–2715. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobsen SJ, Girman CJ, Guess HA, et al. Do prostate size and urinary flow rates predict health care-seeking behavior for urinary symptoms in men? Urology. 1995;45:64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(95)96766-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meigs JB, Barry MJ, Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Kawachi I. High rates of prostate-specific antigen testing in men with evidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Med. 1998;104:517–525. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oesterling JE, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen in a community-based population of healthy men: establishment of age-specific reference ranges. JAMA. 1993;270:860–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armenian HK, Lilienfeld AM, Diamond EL, Bross IDJ. Relation between benign prostatic hyperplasia and cancer of the prostate. A prospective and retrospective study. Lancet. 1974;2:115–117. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91551-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammarsten J, Högstedt B. Calculated fast-growing benign prostatic hyperplasia—a risk factor for developing clinical prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2002;36:330–338. doi: 10.1080/003655902320783827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bostwick DG, Cooner WH, Denis L, Jones GW, Scardino PT, Murphy GP. The association of benign prostatic hyperplasia and cancer of the prostate. Cancer. 1992;70(Suppl):291–301. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1+<291::aid-cncr2820701317>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ. Limitations of using outcomes in the placebo arm of a clinical trial of benign prostatic hyperplasia to quantify those in the community. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:759–764. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]