Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To examine whether the association between hypertension and decline in gait speed is significant in well-functioning older adults and whether other health-related factors, such as brain, kidney, and heart function, can explain it.

DESIGN

Longitudinal cohort study.

SETTING

Cardiovascular Health Study.

PARTICIPANTS

Of 2,733 potential participants with a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, measures of mobility and systolic blood pressure (BP), no self-reported disability in 1992 to 1994 (baseline), and with at least 1 follow-up gait speed measurement through 1997 to 1999, 643 (aged 73.6, 57% female, 15% black) who had received a second MRI in 1997 to 1999 and an additional gait speed measure in 2005 to 2006 were included.

MEASUREMENTS

Mixed models with random slopes and intercepts were adjusted for age, race, and sex. Main explanatory factors included white matter hyperintensity progression, baseline cystatin-C, and left cardiac ventricular mass. Incidence of stroke and dementia, BP trajectories, and intake of antihypertensive medications during follow-up were tested as other potential explanatory factors.

RESULTS

Higher systolic BP was associated with faster rate of gait speed decline in this selected group of 643 participants, and results were similar in the parent cohort (N = 2,733). Participants with high BP (n = 293) had a significantly faster rate of gait speed decline than those with baseline BP less than 140/90 mmHg and no history of hypertension (n = 350). Rates were similar for those with history of hypertension who were uncontrolled (n = 110) or controlled (n = 87) at baseline and for those who were newly diagnosed (n = 96) at baseline. Adjustment for explanatory factors or for other covariates (education, prevalent cardiovascular disease, physical activity, vision, mood, cognition, muscle strength, body mass index, osteoporosis) did not change the results.

CONCLUSION

High BP accelerates gait slowing in well-functioning older adults over a long period of time, even for those who control their BP or develop hypertension later in life. Health-related measurements did not explain these associations. Future studies to investigate the mechanisms linking hypertension to slowing gait in older adults are warranted.

Keywords: hypertension, brain, older adults, MRI

High blood pressure (BP) in older adults is associated with poor physical function and physical disability.1-7 The association between high BP and physical functional limitations has been demonstrated in a number of cohort studies of aging and is known to persist over periods of up to 5 years. Whether these associations also remain significant in well-functioning older adults and for longer periods is unknown. Studies of the explanatory factors of the association between hypertension and physical functional limitations are also scarce. These questions have public health implications. The prevalence of hypertension has been strikingly high since the mid-1900s,8 and hypertension prevention and control remain substantial public health concerns in the United States, where one-third of adults with hypertension are untreated and fewer than half (43%) are successfully controlled.9 With a rapidly aging population, the number of well-functioning older adults exposed to hypertension and at risk for physical disability is also rapidly increasing. The ability to walk at an acceptable speed is important for social and functional activities, and it is central to the independence of older adults in the community.10 Finally, physical functional limitations increase the risk of hospitalization and death,11 and slower walking pace is an important prognostic factor for dementia, disability, and mortality.12-16

It was hypothesized that vascular brain abnormalities, measured on brain MRI as white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), are potential explanatory factors of the association between hypertension and physical function. This hypothesis is based on the evidence that hypertension is associated with greater numbers of WMHs17-25 and on recent work indicating that greater numbers of WMHs are also associated with impaired mobility and slower gait.26-39 The hypothesis that, in older adults free from physical disability, high BP is associated with a more-rapid decline in gait speed over time was first tested. It was further hypothesized that an effect of high BP on vascular disease of the brain, measured as progression of WMHs, mediates gait slowing. The hypothesis that the association between hypertension and faster gait slowing is independent of possible dysfunction of kidney and heart was also tested.

METHODS

Study Population

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a multicenter, population-based, longitudinal study of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in 5,888 older adults.40 An initial 5,201 participants were recruited in 1989/90, with 687 black participants added to the study in 1992/93. The institutional review boards at all sites approved the protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent. Cohort characteristics and prevalence of comorbid conditions in the CHS are similar to those of the Medicare population.41,42 Briefly, participants received annual in-person visits through 1999 and have had ongoing semiannual telephone interviews twice per year for new diagnoses, hospitalizations, procedures, and disability. To enhance the complete ascertainment of events, hospitalization data from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services records were also obtained to identify missing hospitalizations.43 Participants received an additional in-person visit in 2006/07 as part of the CHS All Stars Study.44

Selection

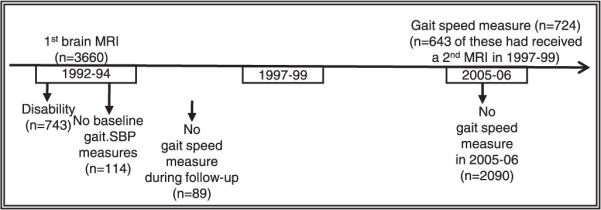

Of the 3,660 CHS participants who had completed a cerebral MRI between 1991 and 1994 (baseline for this study),29 those who had a self-reported disability (defined as persistent walking difficulty or difficulty with one or more activity of daily living (ADL) difficulties,) were excluded (n = 724. Exclusion of those with missing information for mobility or systolic BP at baseline (n = 114) and without at least one follow-up measure through 1997 to 1999 (n = 89) yielded a sample size of 2,733 participants. Of these, 724 had a gait speed test in 2006/07. For this study, the analyses focus on the 643 participants who also received a brain MRI between 1997 and 1999 (Figure 1). Supplementary analyses were conducted of the parent cohort of 2,733 and of the 724 participants with one MRI only (at baseline) to examine whether selection and survivor bias affect the results.

Figure 1.

Selection of the study sample. MRI = magnetic resonance image; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Measurements

Centrally trained and certified staff took all measurements. Quality assurance and control protocols were regularly implemented.40

Exposure to high BP was assessed at the 1992 to 1994 in-person visit (baseline) using actual BP measurements and assessing prior hypertension diagnosis. Presence of prior hypertension diagnosis was based on self-report of hypertension (answering “yes” to the question: “Has the doctor ever told you that you have hypertension?”) or antihypertensive medication intake (classified based on an inventory of medications brought to the clinic at the time of the in-person visit). These measures were used to identify four groups: no exposure (BP < 140/90 at baseline, and the absence of prior hypertension diagnosis or antihypertensive medications intake), recent exposure or newly diagnosed hypertension (BP ≥140/90 at baseline and the absence of prior hypertension diagnosis or antihypertensive medications intake), previous exposure or controlled hypertension (BP < 140/90 at baseline and the presence of prior hypertension diagnosis or antihypertensive medications intake), and previous exposure or uncontrolled hypertension (BP ≥140/90 at baseline, and the presence of prior hypertension diagnosis or antihypertensive medications intake).

The main dependent variable was change in gait speed from baseline to follow-up measured yearly between 1992 and 1997 and again in 2005/06. Gait speed was measured as the time needed to walk a 15-foot course (4.57 m) at usual pace beginning from a still-standing position. The time was recorded using a stopwatch (to 0.1 seconds). The average time in seconds of two trials was converted into m/s and used as a continuous variable at each year. Change over time was modeled as described below in statistical analyses.

WMHs and brain infarcts were measured on brain MRI obtained in 1992 to 1994 and in 1997 to 1999 as previously described.31,45 Briefly, MRI protocols were centrally established, and quality controls and assurances were regularly implemented at all sites. Centrally trained and certified neuroradiologists evaluated the MRIs and rated the presence and severity of WMHs and brain infarcts. WMHs were quantified according to an atlas of predefined visual standards at baseline and follow-up19,29 on standardized sagittal axial spin-density/T2-weighted images. The severity of WMHs was graded on a 10-point scale (0–2 = minimal, 3–4 = moderate, 5–9 = severe). WMH progression from baseline to follow-up was quantified by rereading the pair of brain MRIs side by side17 and defined as the difference of 1 grade or greater between the follow-up and baseline scans. Brain infarcts were defined as areas of abnormal signal intensity in a vascular distribution that lacked mass effect, were brighter than the gray matter on spin-density and T2-weighted images, and 3-mm or larger in size. Infarcts in the white matter or brain stem also had to be hypointense on T1-weighted images.33

Cystatin-C was quantified from frozen samples collected at the baseline visit using a BNII nephelometer (Siemens, Deerfield, IL); values were used as measures of kidney integrity.46 Left ventricular mass was quantified using two-dimensionally directed M-mode images from parasternal short-axis recordings; values were used as measures of heart integrity.47

Covariates

Age, race, sex, education, and conditions known to be associated with slower gait 48 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics at Baseline (1992–1994) for Those Excluded and Those Included in the Study Stratified According to Exposure to High Blood Pressure Measured at Baseline

| Included (n = 643) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Excluded (n = 5,245) |

No (n = 350) |

Recent or Newly Diagnosed (n = 96) |

Previous or Controlled Hypertension (n = 87) |

Previous or Uncontrolled Hypertension (n = 110) |

| Black, n (%) | 827 (15.8) | 39 (11.1) | 12 (12.5) | 19 (21.8)* | 27 (24.6)† |

| Female, n (%) | 3,000 (57.2) | 206 (58.9) | 55 (57.3) | 60 (69.0) | 72 (65.5) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 75.5 ± 5.6 | 72.1 ± 3.3 | 72.6 ± 3.2 | 72.1 ± 3.2 | 72.4 ± 4.2 |

| Education, >12 years, n (%) | 2,199 (41.9) | 205 (58.6) | 57 (58.3) | 47 (54.0) | 49 (44.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean ± SD | 137.4 ± 21.9 | 120.0 ± 11.8 | 146.6 ± 6.6‡ | 124.6 ± 11.4† | 158.3 ± 15.0‡ |

| Gait speed, m/s, mean ± SD | 0.87 ± 0.24 | 1.01 ± 0.21 | 1.04 ± 0.20 | 1.03 ± 0.23 | 1.00 ± 0.18 |

| Male | 1.02 ± 0.21 | 1.06 ± 0.19 | 1.12 ± 0.26* | 1.05 ± 0.21 | |

| Female | 1.00 ± 0.21 | 1.02 ± 0.21 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 0.98 ± 0.16 | |

| Potential explanatory factors | |||||

| White matter hyperintensity progression >0, n (%) | 141 (41.0) | 44 (46.8) | 33 (38.8) | 48 (44.4) | |

| Small brain infarct progression > 0, n (%) | 306 (89.0) | 78 (83.0) | 70 (82.4) | 91 (84.3) | |

| Cystatin-C, mg/L, mean ± SD | 1.14 ± 0.36 | 0.98 ± 0.17 | 1.00 ± 0.22* | 1.02 ± 0.19* | 1.01 ± 0.18 |

| Left ventricular mass, g, mean ± SD | 156.9 ± 40.2 | 148.2 ± 33.0 | 156.6 ± 31.9 | 152.7 ± 23.7 | 151.3 ± 30.2 |

| Other covariates | |||||

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 429 (8.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0(0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Impaired vision, n (%) | 717 (13.7) | 48 (13.9) | 10 (10.5) | 13 (15.1) | 20 (18.7) |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score, mean ± SD |

5.7 ± 5.0 | 4.0 ± 4.0 | 3.6 ± 3.8 | 3.9 ± 3.5 | 3.8 ± 3.6 |

| Modified Mini-Mental State Examination score, mean ± SD |

88.9 ± 10.8 | 94.4 ± 4.8 | 94.4 ± 5.1 | 93.5 ± 5.2 | 92.8 ± 5.9* |

| Physical activity level, kcal × 1,000, mean ± SD | 1.33 ± 1.7 | 1.87 ± 1.92 | 1.90 ± 2.07 | 1.73 ± 1.58 | 1.77 ± 1.72 |

| Obese (body mass index ≥30.0 kg/m2), n (%) | 915 (17.4) | 37 (10.6) | 18 (19.0)* | 21 (24.1)† | 19 (17.3) |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | 448 (8.5) | 23 (6.82) | 2 (2.17) | 8 (9.52) | 6 (5.83) |

| Grip strength, kg, mean ± SD | 27.5 ± 9.9 | 29.6 ± 9.7 | 30.6 ± 9.8 | 26.9 ± 10.4* | 29.1 ± 10.0 |

P< .05 compared with the group without hypertension.

P< .005 compared with the group without hypertension.

P< .001 compared with the group without hypertension.

SD = standard deviation.

Prevalent cardiovascular diseases included baseline history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or atrial fibrillation; presence of a pacemaker; history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; history of angina pectoris or use of nitroglycerine; and history of claudication, peripheral vascular surgery, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or carotid artery surgery. Systolic BP, antihypertensive medication intake, and stroke events were recorded at baseline and during the follow-up period and entered into the model as time-dependent covariates. An ankle–arm index (AAI) less than 0.90 was used as an indication of leg peripheral arterial disease.49,50

Other factors included obesity (body mass index >30.0 kg/m2) and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes mellitus was assessed on the basis of self-report, a doctor’s diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, use of oral hypoglycemic medications or insulin, or a fasting blood glucose of 6.1 mmol/L or higher. Grip strength was used as a proxy for muscle strength and measured as the average strength in kg from two handheld dynamometer trials using the dominant hand.51,52

Other covariates included self-rated health, self-reported regular leisure-time physical activity level (kcal) from the last 12 months, and smoking history (ever vs never). Cognitive function was assessed using the modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS)48 and mood using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D),53 and these were considered to be potential confounders because of their association with hypertension and mobility impairment.54

Statistical Analyses

Differences in baseline characteristics between included and excluded participants were tested using the chi-square test, Student t-test, or Wilcoxon test as appropriate. Because of known race and sex differences in hypertension prevalence,8 analyses were repeated stratified according to race and sex.

Random slopes and intercepts from longitudinal mixed models were used to examine the association between hypertension status and gait speed decline. Each of the three groups with hypertension was compared with the group without hypertension, and a Sidak correction factor for multiple comparisons was applied. The Sidak factor, computed as 1 – (1 – α)l/c (c = number of comparisons and α = confidence level; α = 0.05 for this study, c = 3) was P =.02. The hypothesis that progression of WMHs or baseline measures of kidney and heart function explained the main association was then tested by examining whether there was a substantial change (>10%) of the coefficient after adding these variables to an age-, race-, and sex-adjusted model.55 Additional models were also adjusted for WMHs measured at the first MRI.

Time-dependent covariates included variables measured during follow-up: incident stroke, incident dementia, systolic BP, and intake of antihypertensive medications at each in-person visit from baseline to follow-up. Models were also adjusted for other contributors to slower gait: education, physical activity, and central (vision, depression, cognition) and peripheral (joint pain or arthritis, muscle strength, body mass index, osteoporosis, peripheral arterial disease) factors.

Internal validity analyses were conducted using continuous measures of systolic BP, pulse pressure (systolic–diastolic BP), or diastolic BP, as well as dichotomous measures of high BP (systolic/diastolic BP ≥140/90). All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance, and all tests of statistical significance were two sided.

RESULTS

The participants in this study (those who were not disabled at baseline and had two brain MRIs and one gait speed measure in 1992–94, at least one follow-up measure, and one additional gait speed measure in 2006/07) were younger and more likely to be white and have more years of education, lower systolic BP, and lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors than those who were excluded (Table 1). Differences between those who were included and excluded were statistically significant for all measures (P<.001). In the parent cohort of 2,733 participants, gait speed was 0.96 (no hypertension), 0.95 (recent hypertension), 0.94 (controlled hypertension), and 0.92 m/s (uncontrolled hypertension) at baseline. These values are lower than those observed in the selected sample for this article (Table 1). Gait speed was significantly lower in participants with uncontrolled hypertension than in those without hypertension (unadjusted P =.005) but not in the other groups.

Approximately half of the cohort included in this study (293/643, 45%) had prior history of or high BP at baseline. Of those with hypertension, the prevalence of treated uncontrolled hypertension was 38%. Those with previously diagnosed hypertension were more likely to be black than the rest of the sample. Participants with hypertension (newly diagnosed and those previously diagnosed and uncontrolled) had faster WMH progression than the rest of the sample, although differences were not significant. Small differences in cystatin-C, peripheral arterial disease, obesity, and cognitive status were found between groups (Table 1).

The three groups with exposure to high BP (newly diagnosed hypertensive and previously diagnosed hypertensive, controlled and uncontrolled) had a significantly faster rate of gait speed decline from baseline through the end of follow-up than the group with no hypertension (P-value <Sidak correction factor of P =.02), as shown in Table 2, Model 1. Further adjustment for the MRI findings and the kidney and heart measures did not change the beta coefficients by more than 10% (Table 2). Results also remained substantially unchanged after adjustment for covariates (Table 2, Model 2) and for the time-dependent covariates measured from baseline through the end of follow-up, including incident dementia, incident stroke, and antihypertensive medication (not shown).

Table 2. Results of Longitudinal Mixed-Model Analyses of Rate of Gait Speed Decline According to Hypertension at Baseline Visit (1992–1994) and Follow-Up Through 2006/07.

|

Exposure to High

Blood Pressure |

Coefficient (95% Confidence Interval)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1* | Model 2 † | Model 3 ‡ | Model 4 ∥ | Model 5 § | |

| No (n = 346) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Recent or newly diagnosed (n = 96) | −0.074 (−0.115, −0.034) <.001 | −0.061 (−0.104, −0.018) .006 | −0.075 (−0.115, −0.034) <.001 | −0.075 (−0.116, −0.034) <.001 | −0.081 (−0.122, −0.040) <.001 |

| Previous or controlled hypertension (n = 87) | −0.071 (−0.111, −0.031) <.001 | −0.057 (−0.099, −0.015) .008 | −0.073 (−0.113, −0.033) <.001 | −0.071 (−0.112, −0.030) <.001 | −0.074 (−0.115, −0.033) <.001 |

| Previous or uncontrolled hypertension (n = 110) | −0.050 (−0.091, −0.009) .02 | −0.040 (−0.084, 0.004) .08 | −0.050 (−0.091, −0.009) .02 | −0.046 (−0.087, −0.004) .03 | −0.052 (−0.093, −0.011) .01 |

Units hypertension status predicting gait speed change from baseline to follow-up are in 0.1 m/s per year.

Adjusted for age, race, sex, and systolic blood pressure (measured over follow-up in person visits).

Adjusted for variables in Model 1 and variables univariately associated with the outcome: education, body mass index, osteoporosis, grip strength, congestive heart failure, self-reported vision, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score, modified Mini-Mental State Examination score, self-reported health, and physical activity.

Adjusted for variables in Model 1 and white matter hyperintensities measured at the follow-up scan minus baseline scan.

Adjusted for variables in Model 1 and cystatin-C.

Adjusted for variables in Model 1 and left ventricular mass.

The association between controlled hypertension and faster gait speed decline remained statistically significant after stratification according to sex and was stronger for men (β = −0.14, unit 0.1 m/s per year, P<.001) than for women (β = −0.08, unit 0.1 m/s per year, P =.047). Associations for those with uncontrolled or recent onset hypertension with gait speed decline were similar in men and women. Further adjustment for other covariates, including baseline WMHs and potential mediators, did not change the association in men or women.

The association between hypertension status (none, previous controlled, previous uncontrolled, recent onset) and gait speed decline was also significant in the larger parent cohort of 2,733 (Supplementary Table 1), and results remained substantially unchanged after adjustment for covariates, including time-dependent covariates. There was also a statistically significant association with rate of gait speed decline when other measures of BP (systolic or diastolic BP, pulse pressure, or hypertension) were entered into the model as predictors for the sample of 643, as well as for the parent cohort of 2,733 participants (not shown).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that hypertension accelerated gait speed slowing in this group of well-functioning community-dwelling older adults over 14 years of follow-up. Specifically, it was estimated that hypertension would accelerate gait speed slowing by 0.1 m/s over the follow-up time, which is a clinically meaningful predictor of conversion to disability.10 The association was significant not only for those with recent exposure to high BP (the newly diagnosed group) and for those whose high BP was uncontrolled (the previously diagnosed and uncontrolled hypertension group), but also for those who had successfully controlled hypertension (the previously diagnosed and controlled hypertension group).

Contrary to the hypotheses, the association between exposure to high BP and gait speed decline was independent of, and was not attenuated by, other risk factors for slower gait. Specifically, the regression coefficient of hypertension status predicting gait slowing did not substantially change after adding those measures and conditions that are known to be associated with hypertension and could be important for gait slowing to the model, including measures of integrity of brain, kidney, and heart, as well as incident stroke and dementia. Health-related measurements did not explain these associations. These negative results were consistent in the numerous internal validity analyses with different hypertension classification.

The mechanisms underlying impaired motor performance in old age are complex and involve many physiological and pathological changes, possibly including vascular-related damage to the musculoskeletal and peripheral nervous systems.56,57 This work focused on the pathway linking hypertension with gait slowing through vascular-related brain abnormalities. The findings do not support a mediation effect of end-organ abnormalities because the associations did not change substantially after adjusting for progression of WMHs or heart or kidney function. Perhaps the timing of brain, heart, and kidney measurements was too close to the BP measures to capture a substantial mediation effect. Exposure to high BP may have incubation periods longer than 5 years before it would determine a substantial change in these end organs. This may explain why the accelerated gait slowing in the group with newly diagnosed hypertension was independent of 5-year WMH progression. Another explanation for the lack of mediation effect could be that the neuroimaging methodologies could not detect microstructural changes of the white matter. Future studies using advanced neuroimaging approaches, for example magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor imaging methods, are warranted to provide more-precise quantitative measures of changes, including demyelination and axonal degeneration.58-60

It was also found that, in older adults with a previous diagnosis of hypertension, those with uncontrolled hypertension had slower gait decline and faster WMH progression than those with controlled hypertension. It is possible that this finding could be due to a floor effect; these participants also had slower baseline gait than those with controlled hypertension and perhaps could not decline any further over time. Additionally, in models adjusted for covariates or cystatin-C (Table 2, Models 2 and 4), differences between this group and the group with no hypertension were not significant after correction for the Sidak factor for multiple comparisons. Future studies are needed to identify possible “adaptive” mechanisms that these participants may have implemented.

These findings add to the current knowledge that high BP is associated with accelerated gait slowing in several ways. First, the association remained significant over a long period. Although previous studies have mostly examined 5-year follow-up periods and relied on fewer measurements of self-reported mobility, this study leveraged the availability of repeated, objective measurements of gait from 1992 to 1994 through 2006/07. Second, the cohort of this study was better functioning than those of other geriatric epidemiological studies that have examined patient populations or older adults with greater burden of vascular disease. This study provides new data on high prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension even in well-functioning older adults and is strikingly similar to the prevalence observed in another large epidemiological study of a group with more inclusive criteria.9 Third, this study examined history of hypertension in combination with actual BP measurements and medication data and measured gait slowing rates separately for four groups. These associations did not change after adjustment for changes in BP or changes in medication regimen during follow-up.

Strengths of this study include a long period of follow-up, comprehensive data on a large cohort of well-functioning older adults living in the community, repeated brain MRI scans, and repeated measures of gait speed, which is a reliable and valid measure of motor performance.61 In particular, repeated outcome measurements augmented the model’s robustness. The rates of progression of WMHs measured in this cohort were consistent with those observed in the parent population, as well as in other studies of older adults.17,27,62

A challenge of large epidemiological studies of hypertension is the lack of consensus on the definition of hypertension. In this study, hypertension was examined based on medication records and self-reported diagnosis, as well as continuous measures of systolic and diastolic BP, pulse pressure, and dichotomous measures of high systolic BP, and systolic BP measurements and antihypertensive drug intake during follow-up were accounted for.

Results of this study may not be generalizable, because participants were included if they were relatively well functioning at baseline, had received both brain MRIs and survived through 2006/07. Thus, those in the highest-risk category may not have been included in the analyses.

The repeated analyses in the parent cohort of 2,733 participants show a significant association between hypertension and gait slowing and indicate that survivor and selection bias did not affect these results. Although the CHS has lower mortality than the entire Medicare population, these differences are small, and there is no reason to expect that the relative risks estimated using CHS data would differ for nonparticipants.41,63 Nonetheless, future studies are needed to confirm the generalizability of these results in other groups of older adults.

A greater understanding of the biological pathway linking hypertension to physical disability is important to improve surveillance and intervention strategies to improve physical functional ability in older adults. Although intervention and descriptive studies indicate that antihypertensive drugs in very old people can significantly reduce rates of major cardiovascular events, mobility performance measures have not been systematically studied as outcomes in the major antihypertensive trials.64 The findings of the current study underscore the importance of including gait speed measures as outcomes for clinical trials of hypertension prevention and treatments and obtaining repeated measures of the integrity of multiple systems, possibly including more-advanced neuroimaging measures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Patricia Kearney and two anonymous reviewers who provided substantial comments that helped improve this manuscript.

The research reported in this article was supported by contracts N01-HC-80007, N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, and N01-HC-45133 and grant U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: CR: study concept and design, interpretation of results, preparation of manuscript. WL, LK, and AN: data collection, interpretation of results, preparation of manuscript. RB, CT, and YD: data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geroldi C, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, et al. Mild cognitive deterioration with subcortical features: Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and association with cardiovascular risk factors in community-dwelling older persons (the InChianti study) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1064–1071. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volpato S, Ble A, Metter EJ, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and objective measures of lower extremity performance in older nondisabled persons: The InChianti study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:621–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volpato S, Blaum C, Resnick H, et al. Comorbidities and impairments explaining the association between diabetes and lower extremity disability: The Women’s Health and Aging Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:678–683. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maty SC, Fried LP, Volpato S, et al. Patterns of disability related to diabetes mellitus in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59A:148–153. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.2.m148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo X, Matousek M, Sundh V, et al. Motor performance in relation to age, anthropometric characteristics, and serum lipids in women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M37–M44. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.1.m37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloem BR, Gussekloo J, Lagaay AM, et al. Idiopathic senile gait disorders are signs of subclinical disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1098–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kattainen A, Koskinen S, Reunanen A, et al. Impact of cardiovascular diseases on activity limitations and need for help among older persons. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:82–88. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gover M. Physical impairments of members of low-income farm families; 11,490 persons in 2,477 rural families examined by the farm security administration, 1940; variation of blood pressure and heart disease with age; and the correlation of blood pressure with height and weight. Public Health Rep. 1948;63:1083–1101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angell SY, Garg RK, Charon Gwynn RC, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and predictors of control of hypertension in New York City. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:46–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.791954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perera S, Studenski S, Chandler JM, et al. Magnitude and patterns of decline in health and function in 1 year affect subsequent 5-year survival. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60A:894–900. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.7.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the Short Physical Performance Battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55A:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, et al. Change in motor function and risk of mortality in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people-results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marquis S, Moore MM, Howieson DB, et al. Independent predictors of cognitive decline in healthy elderly persons. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:601–606. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montero-Odasso M, Schapira M, Soriano ER, et al. Gait velocity as a single predictor of adverse events in healthy seniors aged 75 years and older. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60A:1304–1309. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.10.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longstreth WT, Jr, Arnold AM, Beauchamp NJ, Jr, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of worsening white matter on serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2005;36:56–61. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149625.99732.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longstreth WT, Jr, Bernick C, Manolio TA, et al. Lacunar infarcts defined by magnetic resonance imaging of 3660 elderly people: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1217–1225. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bots ML, van Swieten JC, Breteler MM, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and atherosclerosis in the Rotterdam Study. Lancet. 1993;341:1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91144-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dufouil C, de Kersaint-Gilly A, Besancon V, et al. Longitudinal study of blood pressure and white matter hyperintensities: The EVA MRI cohort. Neurology. 2001;56:921–926. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeer SE, Koudstaal PJ, Oudkerk M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2002;33:21–25. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uehara T, Tabuchi M, Mori E. Risk factors for silent cerebral infarcts in subcortical white matter and basal ganglia. Stroke. 1999;30:378–382. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.2.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havlik RJ, Foley DJ, Sayer B, et al. Variability in midlife systolic blood pressure is related to late-life brain white matter lesions: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Stroke. 2002;33:26–30. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Leeuw FE, De Groot JC, Oudkerk M, et al. Aortic atherosclerosis at middle age predicts cerebral white matter lesions in the elderly. Stroke. 2000;31:425–429. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, et al. Magnetic resonance abnormalities and cardiovascular disease in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 1994;25:318–327. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo X, Steen B, Matousek M, et al. A population-based study on brain atrophy and motor performance in elderly women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56A:M633–M637. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitman GT, Tang Y, Lin A, et al. A prospective study of cerebral white matter abnormalities in older people with gait dysfunction. Neurology. 2001;57:990–994. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.6.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfson L, Wei X, Hall CB, et al. Accrual of MRI white matter abnormalities in elderly with normal and impaired mobility. J Neurol Sci. 2005;232:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue NC, Arnold AM, Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. Sulcal, ventricular, and white matter changes at MR imaging in the aging brain: Data from the cardiovascular health study. Radiology. 1997;202:33–39. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.1.8988189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baloh RW, Yue Q, Socotch TM, et al. White matter lesions and disequilibrium in older people. I. Case-control comparison. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:970–974. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340062013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longstreth WT, Jr, Manolio TA, Arnold A, et al. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 1996;27:1274–1282. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camicioli R, Moore MM, Sexton G, et al. Age-related brain changes associated with motor function in healthy older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:330–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longstreth WT, Jr, Dulberg C, Manolio TA, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of brain infarcts defined by serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2002;33:2376–2382. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032241.58727.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tell GS, Lefkowitz DS, Diehr P, et al. Relationship between balance and abnormalities in cerebral magnetic resonance imaging in older adults. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:73–79. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starr JM, Leaper SA, Murray AD, et al. Brain white matter lesions detected by magnetic resonance [correction of resonance] imaging are associated with balance and gait speed. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:94–98. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benson RR, Guttmann CR, Wei X, et al. Older people with impaired mobility have specific loci of periventricular abnormality on MRI. Neurology. 2002;58:48–55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmelli D, DeCarli C, Swan GE, et al. The joint effect of apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and MRI findings on lower-extremity function and decline in cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55A:M103–M109. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sachdev PS, Wen W, Christensen H, et al. White matter hyperintensities are related to physical disability and poor motor function. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:362–367. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.042945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosano C, Kuller LH, Chung H, et al. Subclinical brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities predict physical functional decline in high-functioning older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:649–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: Design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiMartino LD, Hammill BG, Curtis LH, et al. External validity of the Cardiovascular Health Study: A comparison with the Medicare population. Med Care. 2009;47:916–923. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318197b104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, et al. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:358–366. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, et al. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman AB, Arnold AM, Sachs MC, et al. Long-term function in an older cohortFthe Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:432–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bryan RN, Wells SW, Miller TJ, et al. Infarctlike lesions in the brain: Prevalence and anatomic characteristics at MR imaging of the elderlyFdata from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Radiology. 1997;202:47–54. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.1.8988191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, et al. Cystatin c and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2049–2060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gardin JM, Wong ND, Bommer W, et al. Echocardiographic design of a multicenter investigation of free-living elderly subjects: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosano C, Newman AB, Katz R, et al. Association between lower digit symbol substitution test score and slower gait and greater risk of mortality and of developing incident disability in well-functioning older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newman AB, Shemanski L, Manolio TA, et al. Ankle-arm index as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study Group. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:538–545. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, et al. Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Heart Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Circulation. 1993;88:837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gale CR, Martyn CN, Cooper C, et al. Grip strength, body composition, and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:228–235. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al Snih S, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Hand grip strength and incident ADL disability in elderly Mexican Americans over a seven-year period. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16:481–486. doi: 10.1007/BF03327406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hajjar I, Yang F, Sorond F, et al. A novel aging phenotype of slow gait, impaired executive function, and depressive symptoms: Relationship to blood pressure and other cardiovascular risks. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A:994–1001. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander NB. Gait disorders in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:434–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb06417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rubino FA. Gait disorders in the elderly. Distinguishing between normal and dysfunctional gaits. Postgrad Med. 1993;93:185–190. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1993.11701693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi T, Murata T, Omori M, et al. Quantitative evaluation of age-related white matter microstructural changes on MRI by multifractal analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2004;225:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pugh KG, Lipsitz LA. The microvascular frontal-subcortical syndrome of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:421–431. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pantoni L. Pathophysiology of age-related cerebral white matter changes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(Suppl 2):7–10. doi: 10.1159/000049143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: Reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26:15–19. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.ten Dam VH, van den Heuvel DM, de Craen AJ, et al. Decline in total cerebral blood flow is linked with increase in periventricular but not deep white matter hyperintensities. Radiology. 2007;243:198–203. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431052111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yazdanyar A, Newman AB. The burden of cardiovascular disease in the elderly: Morbidity, mortality, and costs. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:563–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gueyffier F, Bulpitt C, Boissel JP, et al. for the INDANA Group Antihypertensive drugs in very old people: A subgroup meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 1999;353:793–796. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.