Abstract

Background

The use of inguinal hernia repair techniques in the community setting is poorly understood.

Methods

A retrospective review of all inguinal hernia repairs performed on adult residents of Olmsted County, MN, from 1989 to 2008 was performed through the Rochester Epidemiology Project.

Results

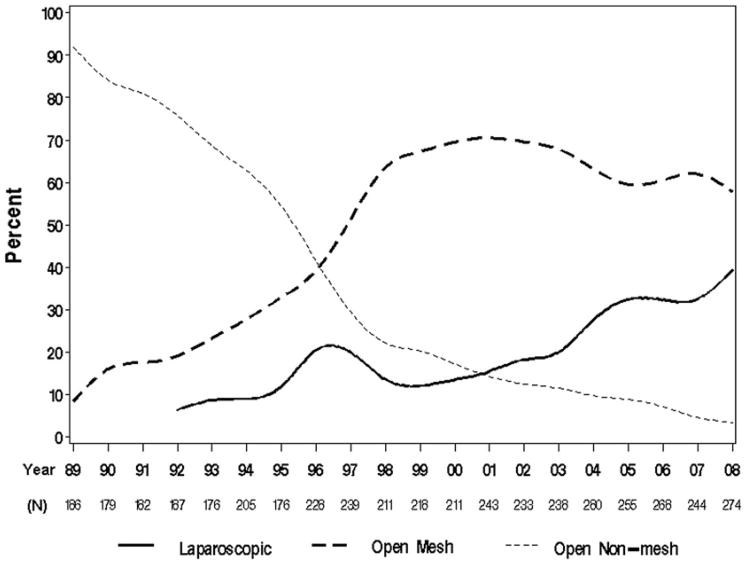

A total of 4,433 inguinal hernia repairs among 3,489 individuals were reviewed. Non–mesh-based repairs predominated in the late 1980s (94% in 1989), declined throughout the 1990s (40% in 1996), and are rarely used nowadays (4% in 2008). Open mesh-based repairs comprised 21% in 1990, peaked in 2001 with 72%, and declined to 55% in 2008. The adoption of laparoscopic repairs began in 1992 (6%) and has increased steadily to 41% in 2008 (P < .001).

Conclusions

Although non–mesh-based repairs, once the predominant method, have been supplanted by open mesh-based techniques, nowadays the use of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair techniques has increased substantially to nearly equal that of open mesh-based techniques.

Keywords: Inguinal hernia, Utilization, Population, Community, Technique, Repair

Abdominal wall hernias collectively are the most common cause of major surgeries performed by general surgeons. Of these, inguinal hernias represent the vast majority. It is estimated that more than 700,000 inguinal hernias are repaired each year in the United States and that 1 in every 4 males will develop an inguinal hernia in his lifetime.1,2 The societal, medical, and economic implications of the management of inguinal hernias are complex and poorly understood.

Costs, both direct and indirect, related to hospital resources and/or days off from work, as well as surgical and patient-reported outcomes, can vary substantially between treatment modalities (ie, laparoscopic vs open repairs, mesh vs nonmesh), setting (inpatient vs ambulatory), surgeon experience, and institution type (academic vs nonacademic medical center).3–5 Despite such perceived variability in care and outcomes in the management of inguinal hernias, there is weak and scarce epidemiologic evidence emanating from population-based studies, particularly US-based studies, because many of the quoted rates are either guesstimates or are outdated (prelaparoscopic era).1,2,6 Therefore, there is a need to determine up-to-date and accurate estimates. To better understand inguinal hernia repair practice patterns, we sought to evaluate the trends in use of inguinal hernia repair techniques over the past 2 decades in the population from Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Methods

With prior institutional review board approval, a retrospective review of all inguinal hernia repairs performed on adult residents of Olmsted County, MN, from January 1, 1989, to December 31, 2008 was performed.

Olmsted County is located in southeastern Minnesota and has a population primarily of northern and central European descent. More than 70% of the population resides in Rochester, the centrally located county seat; the remainder of the county is rural. The local economy is based on farming, health care, and light industry. To be included in the study, patients were required to reside within the county limits at the time of the inguinal hernia repair. Patients who moved to the county for their inguinal hernia repair thus were excluded. We ascertained cases through the records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP),7 which provides the infrastructure for indexing and linking essentially all medical information of the county population. The REP covers and provides access to more than 97% of the population in Olmsted County (124,177 in the year 2000). Each provider in the community uses a dossier system (or unit record) in which all medical information for each individual is accumulated in a single record. Medical diagnoses, surgical interventions, and other key information from the medical records are abstracted routinely in a summary record (master sheet) and entered into computerized indexes using the International Classification of Diseases, Adapted Code for Hospitals. We ascertained potential cases of inguinal hernia repairs (both primary and recurrent) by searching the indexes for the following International Classification of Diseases, Adapted Code for Hospitals diagnostic: 550.91, 550.93, 550.01, 550.03, 550.11, 550.13, and Current Procedural Terminology codes: 53.00 to 53.17, and 17.11 to 17.24. The records of all patients with at least one of the aforementioned codes entered during the study period were screened by the study team using a specifically designed form and following an instruction manual. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic.8 Inguinal hernia repair techniques were obtained directly from the surgical note, either as directly stated by the surgeon or from reading the surgical description; surgical techniques were classified into major categories according to their main surgical principle: open nonmesh, open mesh, and laparoscopic. Each major classification was subdivided further into minor subgroups according to individual techniques (ie, open nonmesh = Bassini, McVay, Shouldice; open mesh = Lichtenstein, Mesh-Plug, Kugel, Prolene Hernia System (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ); laparoscopic = transabdominal, totally extraperitoneal). Because of the myriad of modifications of the original surgical descriptions, each modification was classified within the same category of the original description as long as they followed the main surgical principle. For example, the so-called plug-stein or plug and patch, the combination of a mesh-plug and Lichtenstein technique, was considered in the mesh-plug category. The senior author (D.R.F.), an experienced hernia surgeon, reviewed all cases of uncertainty in the surgical technique.

Univariate associations between type of repair and patient- and hernia-related characteristics were evaluated with the chi-square, Kruskal–Wallis, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate these associations after adjusting for year of surgery. Trends over time were evaluated with the Cochran–Armitage trend test. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All tests were 2-sided and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 4,433 inguinal hernia repairs among 3,489 individuals (321 women, 3,168 men; mean age, 54 ± 18 y) were performed during the study period, ranging from 176 to 280 repairs per year. The use of surgical techniques greatly varied by year: non–mesh-based repairs predominated in the late 1980s (94% in 1989), declined throughout the 1990s (40% in 1996), and rarely are used in current day practice (4% in 2008). Open mesh-based repairs comprised 21% in 1990, peaked in 2001 at 72%, and declined to 55% in 2008. The adoption of laparoscopic hernia repairs began in 1992 (6%) and has increased steadily to 41% in 2008 (P < .001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in the utilization of inguinal hernia repair techniques.

No major changes over time were seen within the non–mesh-based category; during the entire study period, the Bassini-type repair was the predominant non–mesh-based repair (range, 47%–86% per year), followed by the McVay repair (range, 0%–24%), hernia sac resection with annuloplasty (range, 0%–18%), and the Shouldice repair (range, 0%–6%).

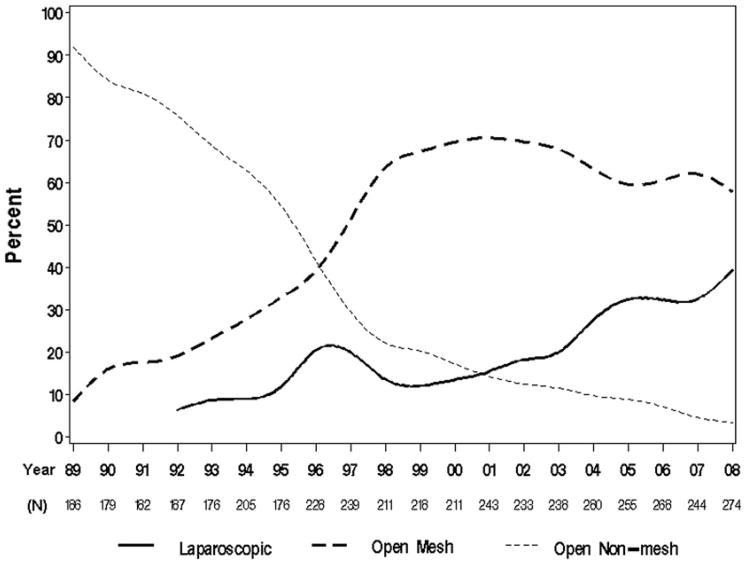

Among mesh-based repairs, the predominant method from 1989 to 1995 was the Lichtenstein repair. In 1995, the mesh-plug repair emerged and became the most common type of mesh-based repair (67% in 1997) until the early 2000s when the adoption of the Lichtenstein technique again increased slightly above that of the mesh-plug (54% vs 44% in 2004), a ratio that has remained relatively constant in the past half a decade (55% vs 39% in 2008) (Fig. 2). The remaining percentage of repairs (<5% –10%) largely are attributed to either open preperitoneal mesh-based repairs in the early 1990s or to the Prolene Hernia System in the 2000s.

Figure 2.

Trends in the utilization of open mesh-based repairs. Other includes Kugel patch, Prolene Hernia System, Rives-Stoppa, and preperitoneal mesh repair.

Laparoscopic repairs were first documented in 1992, performed predominantly (100%) by the transabdominal approach. The first cases of the totally extraperitoneal approach were documented in 1995 (17%) and swiftly became the most common laparoscopic approach by 1997 (totally extraperitoneal = 60% vs transabdominal approach = 40%). Such totally extraperitoneal over transabdominal approach predominance increased to an 80% to 90% range in the year 2000 and has remained constant until current day. For the entire study period, the use of laparoscopy for bilateral and recurrent hernias was 43% and 18%, respectively; however, in 2008 this increased to 65% and 30%, respectively.

Laparoscopic repairs were more likely to be performed in the elective setting (>99% vs 97%), in a younger (mean age ± standard deviation, 51 ± 15 vs 55 ± 18), healthier (%American Society of Anesthesiologist Risk Classification (ASA) I, 33 vs 27), male (97% vs 90%) individual with bilateral (61% vs 18%), direct (43% vs 31%) hernias when compared with open techniques, respectively, even after adjusting for year of repair (all P < .05). Body mass index (median body mass index, 26.1 vs 25.7 kg/m2), side (left side, 48% vs right side, 46%), recurrent hernia (11% vs 11%), outpatient setting (81% vs 73%), or the need for an additional procedure (10% vs 11%) were not associated with the repair being performed in either a laparoscopic or open approach after adjusting for year of surgery, respectively (all P > .05).

Comments

This study showed that the use of inguinal hernia repair techniques has changed substantially over time. Open non–mesh-based techniques, once the mainstay treatment, rarely are used in current day practice. Open mesh-based techniques became the most common type of repair in the mid-1990s, however, the adoption of laparoscopic repairs has increased to nearly equal that of open mesh-based repairs, with this study documenting the highest (41%) use rate to date.

Smink et al5 examined the use of laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repairs in Florida during 2002–2003 and found a 19.5% use rate of laparoscopic techniques in the outpatient setting. Despite its proven effectiveness and favorable postoperative pain profile,4 the adoption of laparoscopic techniques for the management of inguinal hernias has been reported to be low in other countries as well. A survey in 2007 documented that only 15% of all surgeons from Wales perform laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs, and none used it as a first choice for a primary hernia.9 Smink et al5 suggested that financial considerations (ie, laparoscopy being more costly) may unduly bias the indications for laparoscopic repairs compared with open repairs, whereas others attribute the steep learning curve associated with laparoscopic hernia repairs to the low adoption of this technique.3 Nonetheless, the indications for laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy have changed over time; nowadays, some surgeons consider it the preferred approach for bilateral inguinal hernias and for recurrent hernias from a previous open repair.10 In Denmark, although laparoscopic repairs accounted for only 16% of all inguinal hernia repairs in 2006, 90% of bilateral hernias and 50% of recurrent hernias were repaired laparoscopically.11 In contrast, this study showed that only 65% of bilateral hernias and 30% of recurrent hernias were repaired laparoscopically in the population of Olmsted County in 2008, hence highlighting the vast differences in hernia care across geographic regions.

Similarly to Smink et al,5 this study showed that laparoscopic repairs were more likely to be performed in younger, healthier individuals in the elective setting. Such findings might be owing to either patient selection by the surgeon in his early learning curve, or to the relative contraindications of the laparoscopic repairs, because patients who either have multiple comorbidities, are unfit for general anesthesia, or who present in the emergent setting might fare better with an open repair. In contrast to the findings of Smink et al,5 this study showed that laparoscopic repairs were more likely to be performed in males, as opposed to females. The reasons for this gender discrepancy are unclear because the benefits from laparoscopic repairs have been shown to be equivalent for both.12 Further research should attempt to clarify these findings.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. The retrospective nature of data collection hinges on the accuracy and completeness of the medical record. Noncoverage bias could exist if residents of Olmsted County sought surgical repair of their inguinal hernia outside of the county, although we believe this issue to be negligible because medical care in the county is readily available. Because confidentiality agreements pertaining to the REP project preclude us from comparing data between participating individuals (ie, surgeons) or institutions, we were unable to evaluate how changes in the physician workforce or case volume affect the use of inguinal hernia repair techniques, and hence represent an opportunity for further study. Furthermore, the population covered by the REP is mostly Caucasian and reflective of the US midwest, therefore such practice patterns seen in this study might not be reflective of that of other populations. However, we believe that because the REP allows access to more than 97% of the population of a defined region, with coverage of academic and nonacademic medical centers as well as inpatient and outpatient procedures, it provides the best appraisal of a US-based population on the topic to date.

In summary, the past 2 decades have seen a radical shift in the treatment of inguinal hernias. Although non–mesh-based repairs, once the predominant method, have been supplanted by open mesh-based techniques, nowadays the use of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair techniques has increased substantially to nearly equal that of open mesh-based techniques. The societal and economic implications of these trends warrant further study.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (grant R01 AG034676) from the National Institute on Aging) and by a grant (1 UL1 RR024150) from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented at the Midwest Surgical Society 54th Annual Meeting, August 7–9, 2011, Galena, IL.

References

- 1.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Risk factors for inguinal hernia among adults in the US population. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1154–61. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:1045–51. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, et al. Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1819–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, et al. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD001785. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smink DS, Paquette IM, Finlayson SR. Utilization of laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair: a population-based analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:745–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson JH, Gofin J, Hopp C, et al. The epidemiology of inguinal hernia. A survey in western Jerusalem. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978;32:59–67. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanjay P, Woodward A. A survey of inguinal hernia repair in Wales with special emphasis on laparoscopic repair. Hernia. 2007;11:403–7. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowne WB, Morgenthal CB, Castro AE, et al. The role of endoscopic extraperitoneal herniorrhaphy: where do we stand in 2005? Surg Endosc. 2007;21:707–12. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg J, Bay-Nielsen M. Current status of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in Denmark. Hernia. 2008;12:583–7. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zendejas B, Onkendi EO, Brahmbhatt RD, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repairs performed by supervised surgical trainees. Am J Surg. 2011;201:379–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.019. discussion 383–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]