Abstract

A balanced chromosomal translocation segregating with schizophrenia and affective disorders in a large Scottish family disrupting DISC1 implicated this gene as a susceptibility gene for major mental illness. Here we study neurons derived from a genetically engineered mouse strain with a truncating lesion disrupting the endogenous Disc1 ortholog. We provide a detailed account of the consequences of this mutation on axonal and dendritic morphogenesis as well as dendritic spine development in cultured hippocampal and cortical neurons. We show that the mutation has distinct effects on these two types of neurons, supporting a cell-type specific role of Disc1 in establishing structural connections among neurons. Moreover, using a validated antibody we provide evidence indicating that Disc1 localizes primarily to Golgi apparatus-related vesicles. Our results support the notion that in vitro cultures derived from Disc1Tm1Kara mice provide a valuable model for future mechanistic analysis of the cellular and biochemical effects of this mutation, and can thus serve as a platform for drug discovery efforts.

Keywords: schizophrenia, hippocampal cultures, cortical cultures, dendritic spines, axons, dendrites

Introduction

A role for rare mutations in schizophrenia is well established (Rodriguez-Murillo et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2011). A rare balanced chromosomal translocation segregating with schizophrenia and affective disorders in a large Scottish family (Millar et al., 2000) implicated DISC1 as a susceptibility gene for major mental illness. Several mouse models have been generated to investigate Disc1 function, and shown to display diverse profiles of behavioral and cellular abnormalities (Clapcote et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2008; Pletnikov et al., 2008; Li et al., 2007; Hikida et al., 2007). These models include mice over-expressing truncated versions of human DISC1 protein under various exogenous or endogenous promoters either constitutively (Hikida et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2008) or transiently during early postnatal life (Pletnikov et al., 2008), as well as mice carrying ENU-induced mutations in the Disc1 gene (Clapcote et al., 2007; Shoji et al., 2012).

The well-defined DISC1 risk allele found in the Scottish pedigree (the only DISC1 mutation unequivocally associated with mental illness), represents a potentially valuable tool for gaining insight into the pathogenesis of mental illnesses. We had previously described a disease-oriented approach (Arguello and Gogos, 2006; Arguello et al., 2010; Arguello and Gogos, 2012) to generate mutant mice carrying a truncating lesion in the endogenous Disc1 orthologue that models the Scottish schizophrenia risk allele (Koike et al., 2006). This mutant mouse strain propagates a Disc1 allele (Mouse Genome Informatics nomenclature: Disc1Tm1Kara) that carries two termination codons (in exons 7 and 8), as well as a premature polyadenylation site in intron 8, which leads to the production of a truncated transcript (Koike et al., 2006). We have previously shown that this genetic lesion results in the elimination of the major isoforms of Disc1 at ~98 kD (predicted full-length protein(s): L and Lv forms, http://genome.ucsc.edu) and ~70 kD in the postnatal and adult brain (Kvajo et al., 2008). It also results in the production of low-levels of a predicted truncated protein product detected, as expected, by an N-terminally directed antibody but not by a C-terminal antibody. Overall, the genetic lesion introduced into the endogenous Disc1 orthologue preserves the endogenous spatial and temporal expression pattern of the gene and mimics key aspects of the Scottish mutation by virtue of the position of the introduced truncating lesions (in the vicinity of the translocation breakpoint) and of the fact that it preserves short N-terminal isoform(s) of the gene (http://genome.ucsc.edu). A comprehensive analysis of these mice revealed robust and highly selective deficits in working memory and implicated malfunction of neural circuits within the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex as contributing to the genetic risk conferred by the DISC1 gene (Koike et al., 2006; Kvajo et al., 2008; Kvajo et al., 2011). Immunocytochemical studies using a variety of antibodies in cultured cells, have localized Disc1 at multiple cellular compartments, including the centrosome, microtubules (Morris et al., 2003), mitochondria (James et al., 2004), nucleus (Sawamura et al., 2005) and cytoplasmic puncta (Brandon et al., 2005). In primary neurons Disc1 has been also localized to the distal part of axons (Taya et al., 2007), cell body and dendritic shafts and spines (Hayashi-Takagi et al., 2010). In vitro studies also suggested that Disc1 may have a role in dendritic and axonal outgrowth. Overexpression of the C-terminally truncated Disc1 inhibited neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells (Ozeki et al., 2003), and shRNA-mediated decrease of endogenous Disc1 in cultured neurons was shown to inhibit axonal elongation (Taya et al., 2007). It has been proposed that some of these effects stem from interactions with centrosomal and cytoskeletal proteins (Wang and Brandon, 2011); however, limited specificity of Disc1 antibodies (Kvajo et al., 2008; Kuroda et al., 2011), and possible off-target effects from overexpression- and shRNA-mediated manipulations (Kvajo et al., 2010) pose challenges in the interpretation of these findings and to our current understanding of the impact of the Scottish allele on various cellular functions.

The purpose of this study is to characterize in detail the impact of the Disc1Tm1Kara allele on the development of primary neurons and compare these findings to neuronal development in vivo. This information is important to facilitate mechanistic studies to determine the factors that modulate the expressivity and penetrance of this genetic lesion during neuronal development and maturation, independently of network level influences and development compensation in the intact organism. A great advantage of using cultured neurons is that they offer a platform for small molecule screens and other drug development approaches.

Using this mouse strain we demonstrate that a mutation in mouse Disc1 resembling a schizophrenia risk allele results in morphological alterations in both the axonal and dendritic arbor and spines of cultured neurons. These deficits were specific to the origin of the primary cells, with hippocampal neurons showing altered axonal and dendritic arborization as well as altered spine formation, while cortical neurons primarily showing alterations in spine development. Notably, comparison of Disc1 protein localization in wild-type (WT) and mutant neurons revealed that Disc1 is specifically localized to the Golgi network raising important questions about the mechanisms underlying its cellular functions.

Results

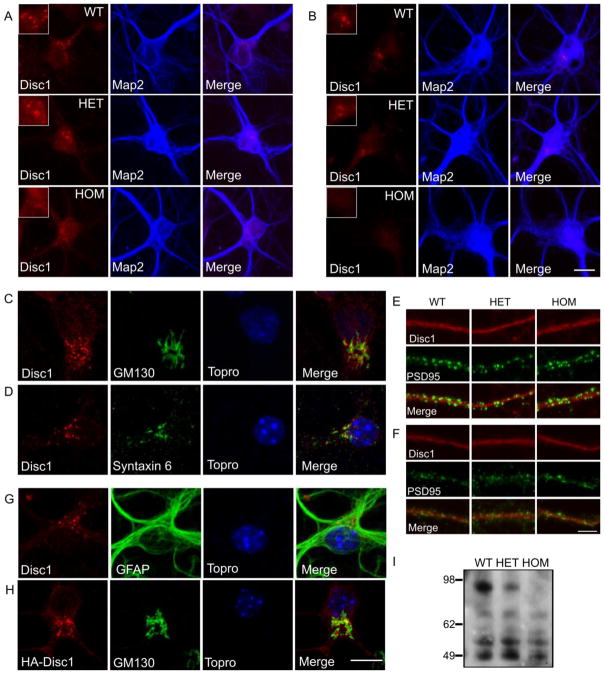

Disc1 is enriched in vesicular structures associated with the Golgi apparatus

We first determined the subcellular localization of endogenous Disc1 in dissociated hippocampal and cortical neurons derived from WT, heterozygous (HET) and homozygous (HOM) Disc1Tm1Kara mice. A detailed analysis in developing and mature neurons was performed using a N-terminal antibody raised in our lab which can specifically detect all major Disc1 isoforms (Koike et al., 2006; Kvajo et al., 2008). Immunofluorescence at different time points during neuronal development revealed a pattern of bright punctuate structures confined to the neuronal soma that were absent in neurons derived from HOM cells (Figure 1A, B). Double immunocytochemistry with markers for organelles in whose function Disc1 has been previously implicated, including mitochondria (James et al., 2004), centrosome, centriolar satellites (Kamiya et al., 2008) and kinesin (Taya et al., 2007), did not show appreciable colocalization (Supplementary Figure 1A–G). In contrast, Disc1 was found in vesicle-like structures juxtaposed to the cis-Golgi marker GM130 (Figure 1C), and partially overlapping with the trans-Golgi marker syntaxin 6 (Figure 1D) suggesting that it is localized to the vesicles of the Golgi network. This observation is consistent with recent results obtained with an independently generated and validated antibody (Kuroda et al., 2011). This distribution could be observed from the first day in culture (DIV1), and was retained throughout neuronal maturation (Supplementary Figure 2). Disc1 immunoreactivity did not colocalize with other components of the endomembrane system, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, the early endosome or the recycling endosome (Supplementary Figure 3A–D), but localized in close proximity to the late endosome, with limited instances of colocalization (Supplementary Figure 4) In mature neurons, Disc1 immunoreactivity was previously described in dendritic spines (Hayashi-Takagi et al., 2010). Our analysis of cortical and hippocampal DIV22 neurons revealed specific and robust expression in Golgi-related structures in the soma of neurons derived from WT but not HOM mice, and a diffuse, weaker signal in the dendrites, which did not differ appreciably among the genotypes (Figure 1). This latter immunoreactivity pattern may reflect non-specific reactivity of the antibody or detection of short N-terminal isoform(s) that are preserved in HOM Disc1Tm1Kara mice. Colocalization analysis with the postsynaptic marker PSD-95 or the presynaptic marker synaptophysin demonstrated that this diffuse immunoreactivity was restricted to the dendritic shaft and did not extent to the spines (Figure 1E, F, data not shown). Finally, analysis of glial cells, identified by their expression of GFAP, also revealed robust Disc1 expression in punctuate structures, which was abolished in glial cells from HOM mice (Figure 1G).

Figure 1. Disc1 localization in primary neurons.

A, B. DIV6 primary neurons from hippocampal (A) and cortical (B) culture from all three genotypes stained with the antibody raised against the N-terminals portion of Disc1. Bright punctuate staining observed in WT and HET, is missing in HOM neurons. Inserts show a magnification of the punctuate signal. Map2 staining (blue) is used to identify neurons.

C, D. Hippocampal primary neurons stained with markers of the Golgi network. Disc1 puncta localize perinucleary, in the vicinity of the cis-Golgi network expressing GM130 (C), and the trans-Golgi network marker syntaxin 6 (D). Nuclei are labeled in blue.

E, F. Hippocampal (E) and cortical (F) DIV22 neurons stained for Disc1 and the presynaptic marker PSD-95 (green). No specific signal is observed in distal dendrites and spines.

G. Disc1-positive puncta are observed in WT GFAP-positive astrocytes.

H. Exogenously expressed HA-Disc1 also localizes to Golgi-associated puncta.

I. Western blotting of Disc1 on lysates of hippocampal cultures. The long Disc1 isoform (98 kDa) is prominently expressed, and missing in HOM cultures. Scale bars: B, H: 10 μm, F: 5 μm

Transfection of neurons with a full-length HA-tagged mouse Disc1 expression construct (Disc1-FL) revealed a similar pattern of expression, with exogenous Disc1 being localized to vesicle-like structures associated with the Golgi network (Figure 1H). This suggested that endogenous Disc1 immunoreactivity represents the long forms of Disc1, which are abolished by Disc1Tm1Kara. This was further confirmed by western blotting of endogenous Disc1, showing that pyramidal neurons in culture abundantly express the long isoforms of Disc1 (Figure 1I).

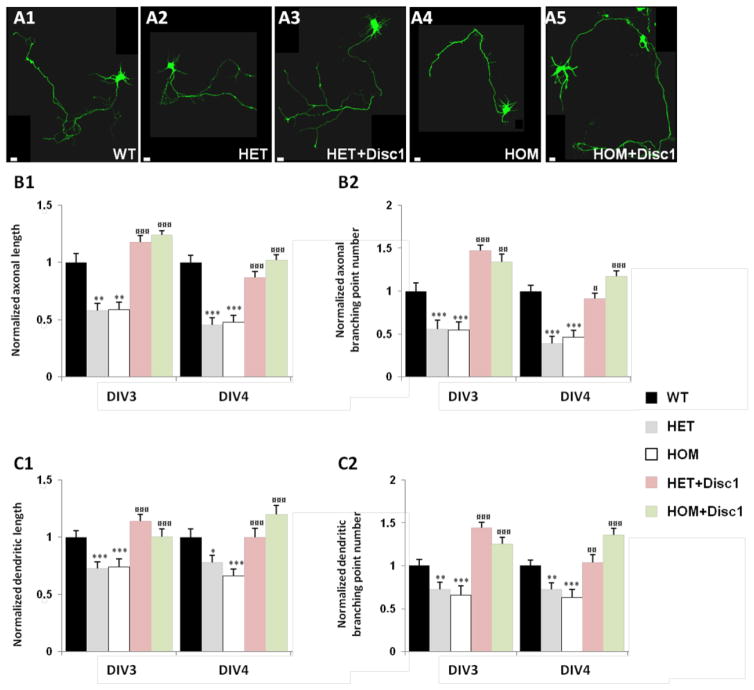

Disc1Tm1Kara alters growth of axons, dendrites and dendritic spines in cultured hippocampal neurons

Alterations in dendritic growth are consistently observed in vivo in the hippocampus of Disc1Tm1Kara mice albeit in a cell-type and developmental-stage specific manner (Kvajo et al., 2008; Kvajo et al., 2011). We have previously shown that these alterations can be recapitulated in cultures from hippocampal neurons harvested from Disc1Tm1Kara embryos (Kvajo et al., 2011). Specifically, cultured DIV5 neurons from HET and HOM mice displayed a less complex dendritic tree than WT neurons, with decreased branch point numbers and total length. Expression of Disc1-FL normalized dendritic length and branching point numbers, confirming that the observed deficits are a direct effect of reduced Disc1 levels. However, how early during neuronal maturation in vitro these Disc1Tm1Kara-dependent deficits in dendritic growth and complexity appear and whether Disc1Tm1Kara also affects axonal growth as well as spine development in cultured neurons remain unknown.

To address these question we used, as previously (Kvajo et al., 2011), Disc1Tm1Kara HOM, HET and WT littermates harvested at E17 to establish hippocampal neuronal cultures. We transfected dissociated neurons at DIV2 with constructs encoding GFP (β-actin-GFP) in order to visualize their morphology (Figure 2A). In complementation experiments designed to re-introduce Disc1 in deficient neurons, both HET and HOM neurons were co-transfected with β-actin-GFP and Disc1-FL. 24 and 48 hours following transfection (at DIV3 and DIV4), we fixed and stained transfected neurons with an anti-MAP2 antibody to identify dendrites, and anti-Tau1 antibody to identify axons (Supplementary Figure 5). The total axonal and dendritic length and the branching point number per transfected cell were measured (Figure 2B, C). HET and HOM neurons displayed a less complex axonal and dendritic network than WT neurons, and these anomalies were observed as early as DIV3. In neurons co-transfected with β-actin-GFP and Disc1-FL expression of exogenous Disc1 reversed axonal and dendritic length and branching point numbers to WT levels. In some instances, we observed an “over-rescue”, where exogenous Disc1 increased axonal and dendritic growth beyond WT levels (Figure 2B, C). Overall, consistent with previous results (Kvajo et al., 2011), our findings confirm that the observed phenotypes are a direct effect of reduced Disc1 levels.

Figure 2. Axonal and dendritic phenotypes in hippocampal Disc1Tm1Kara neurons.

A. DIV5 hippocampal neurons, WT (A1), HET (A2) and HOM (A4) transfected at 2 days in culture with β-actin-GFP or β-actin-GFP+Disc1 plasmid (A3, A5).

B. Axonal complexity in neurons transfected with GFP at DIV2 and fixed at DIV3 and DIV4. Quantification of axonal length (B1) and axonal branching point number (B2) at DIV3 (n=63, 54 and 53 HET, HOM and WT respectively), and at DIV4 (n=52, 54 and 52 HET, HOM and WT respectively). Transfection with exogenous Disc1 rescued axonal length (B1) and axonal branching points (B2) at all time points; DIV3 (n=70 and 48 respectively) and DIV4 (n=54 and 44 respectively). (Axonal length: p=8.7E−06, p=1.0E−06 at DIV3, and p=1.9E−10, p=6.5E−10 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs WT; p=1.3E−16, p=4.6E−13 at DIV3 and p=2.1E−11, p=6.2E−15 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1 respectively. Axonal branching point: p=2.0E−04, p=1.1E−04 at DIV3 and p=4.0E−08, p=1.0E−06 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs WT; p=5.9E−13, p=7.4E−09 at DIV3 and p=1.4E−11, p=7.0E−12 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1 respectively.) In some cases we observed an “over-rescue” when transfecting with exogenous Disc1 (axonal length: p=2.8E−02 at DIV3 and p=2.8E−02 at DIV4 for HOM+Disc1 vs WT), (axonal branching point: p=7.1E−04 for HET+Disc1 vs WT and p=2.6E−02 for HOM+Disc1 vs WT at DIV3).

C. Dendritic complexity in neurons transfected with GFP at DIV2 and fixed at DIV3, and DIV4. Quantification of dendritic length (C1) and dendritic branching point number (C2) at DIV3 (n=329, 246 and 342 HET, HOM and WT respectively), and at DIV4 (n=265, 277 and344 HET, HOM and WT respectively). Transfection with exogenous Disc1 rescued dendritic length (C1) and dendritic branching points (C2) at all time points DIV3 (n=426 and 287 respectively), and DIV4 (n=340 and 268 respectively). (Dendritic length: p=1.7E−04, p=6.7E−04 at DIV3 and p=1.1E−02, p=1.1E−04 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs WT; p=3.7E−07, p=1.6E−03 at DIV3 and p=1.5E−02, p=2.0E−07 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1 respectively. Dendritic branching point: p=2.7E−03, p=4.4E−04 at DIV3 and p=6.4E−03, p=2.6E−04 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs WT; p=7.1E−10, p=8.3E−07 at DIV3 and p=5.4E−03, p=2.7E−09 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1 respectively). In some cases we observed an “over-rescue” in cells transfected with exogenous Disc1 (dendritic branching point: p=4.1E−04 for HET+Disc1 vs WT, and p=4.0E−02 for HOM+Disc1 vs WT at DIV3, p=6.8E−03 for HOM+Disc1 vs WT at DIV4).

*p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.0005 against WT.

¤p<0.05; ¤¤p<0.005; ¤¤¤p<0.0005 against HET or HOM.

Scale bar: 10μm

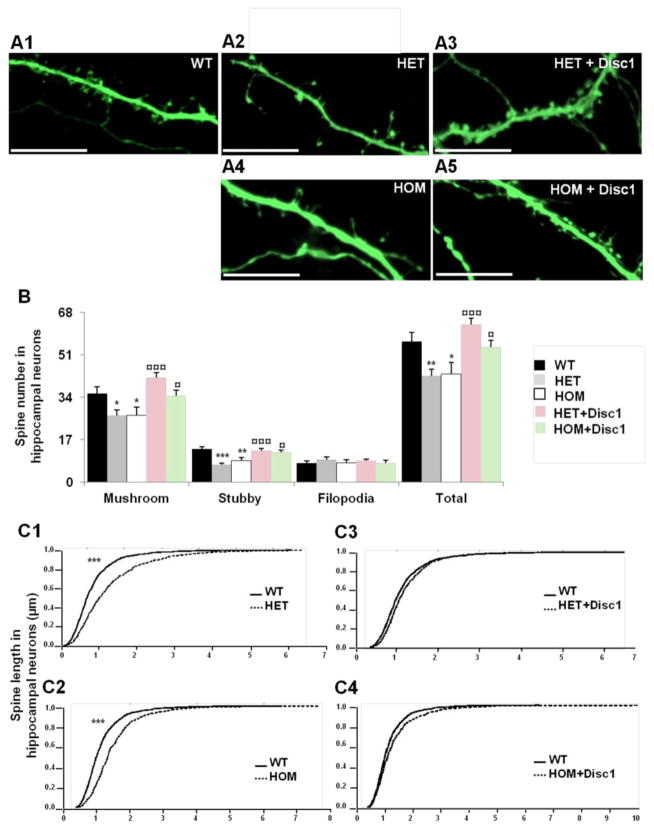

We next examined whether Disc1Tm1Kara affects the density and morphology of dendritic spines. We transfected hippocampal neuronal cultures at DIV8 with constructs encoding GFP and viewed the spine morphology of GFP-positive pyramidal neurons at DIV22 (Figure 3A). Analysis of dendritic spine development showed that spine density was reduced in both HET and HOM neurons (Figure 3B), with a significant decrease in spine density for both mushroom and stubby morphotypes, while the density of filopodia was not significantly affected. Morphometric analysis of mushroom spines showed a small, but statistically significant increase in the head-width and length (Figure 3C). The average spine head-width was increased by 10.9% in HET and 17.4% in HOM neurons and the average length was increased by 38.3% and 30.4 % compared to WT neurons (p<1.0E−04). Complementation experiments confirmed that the observed reduction in spine density is a direct effect of reduced Disc1 levels since both HET and HOM neurons transfected with the Disc1-FL construct showed a restoration of the spine size and density to nearly WT levels (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Alterations in dendritic spines of Disc1Tm1Kara hippocampal neurons.

A. Dendritic spines from WT (A1), HET (A2–A3) and HOM (A4–A5) hippocampal neurons transfected at DIV8 with β-actin-GFP (A1, A2, A4) or β-actin-GFP+Disc1 construct (A3, A5) and fixed at DIV22.

B. Spine density (number of spines per 75 μm of dendrite) was reduced in both HET and HOM neurons (n=26, 23 and 12 for HET, HOM and WT respectively) (p=4.3E−03 and p=1.4E−02 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively). Mushroom (p=2.3E−02 and p=2.9E−02 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively) and stubby spines (p=1.6E−06 and p=8.6E−04 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively) were both affected. Transfection with exogenous Disc1 rescued the phenotype in both HET and HOM neurons (n=31 and 15, respectively) (p=4.8E−07 and p=1.9E−02 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1, respectively). Mushroom (p=4.4E−06 and p=2.8E−02 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1, respectively) and stubby spines (p=2.7E−07 and p=2.1E−02 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1, respectively) were both rescued.

C. Dendritic spine length analysis per 75 μm dendritic length of hippocampal neurons. Mushroom spines displayed an increase in head-width and head-length in both HET and HOM neurons (C1, C2) (n= 615, 561 and 920 for HOM, HET and WT respectively) (p<1.0E−04 for HET and HOM vs WT). Transfection with exogenous Disc1 rescued the head-length phenotype in both HET and HOM neurons (C3, C4) (n=1839 and 548, respectively) (p=3.0E−03 and p=1.0E−02 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1).*p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.0005 against WT.

¤p<0.05; ¤¤p<0.005; ¤¤¤p<0.0005 against HET or HOM.

Scale bar: 10μm

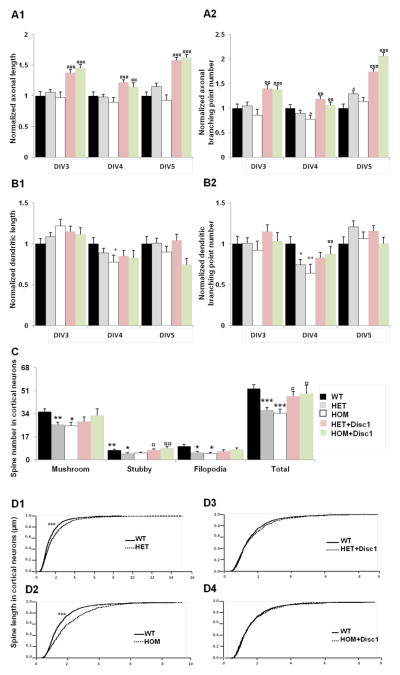

Disc1Tm1Kara alters growth of dendritic spines but not dendrites or axons in cultured cortical neurons

We repeated the experiments described above on cortical primary neurons. As for hippocampal cultures, we transfected cortical neurons at DIV2 with constructs encoding GFP in order to visualize their morphology. In contrast to hippocampal neurons, we did not observe significant changes in axonal and dendritic complexity of HET and HOM cortical neurons at DIV3 and DIV5. A modest and transient decrease was found at DIV4 (Figure 4A, B). Expression of Disc1-FL did not significantly change dendritic parameters, but it increased axonal length and branching in all three genotypes and at all time points.

Figure 4. Axonal and dendritic phenotypes in cortical Disc1Tm1Kara neurons.

A. Analysis of axonal complexity of neurons transfected at DIV2 and fixed at DIV3, DIV4 and DIV5. Quantification of total axonal length (A1) and axonal point number (A2) at DIV3 (n=82, 40 and 48 HET, HOM and WT respectively), at DIV4 (n=81, 40 and 49 HET, HOM and WT respectively) and at DIV5 (n=56, 41 and 49 HET, HOM and WT, respectively). Transfection with exogenous Disc1 did affect axonal length (A1) and branching points (A2) at all time points DIV3 (n=59 and 41 respectively), DIV4 (n=62 and 41 respectively) and DIV5 (n=60 and 41 respectively). (Axonal length: p=1.0E−02 at DIV5 for HET vs WT; p=2.0E−04, p=1.1E−04 at DIV3, p=9.2E−04, p=2.2E−02 at DIV4 and p=2.9E−05, p=7.8E−08 at DIV5 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1 respectively. Axonal branching point: p=1.0E−02 at DIV4 for HOM vs WT; p=5.9E−03, p=9.6E−04 at DIV3, p=2.7E−03, p=2.6E−03 at DIV4 and p=5.7E−04, p=1.2E−06 at DIV5 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1 respectively.) In some cases we observed an “over-rescue” in cells transfected with exogenous Disc1 (axonal length: p=3.6E−04 and p=6.2E−05 at DIV3 for HET+Disc1 vs WT, and HOM+Disc1 vs WT; p=1E−02 at DIV4 for HET+Disc1 vs WT; p=2.5E−07 and p=9.5E−08 at DIV5 for HET+Disc1 vs WT, and HOM+Disc1 vs WT), (axonal branching point: p=4.1E−03 and p=6.4E−03 at DIV3 for HET+Disc1 vs WT, and HOM+Disc1 vs WT; p=1E−02 at DIV4 for HET+Disc1 vs WT; p=3.3E−07 and p=2.6E−08 at DIV5 for HET+Disc1 vs WT, and HOM+Disc1 vs WT).

B. Analysis of dendritic complexity of neurons transfected at DIV2 and fixed at DIV3, DIV4 and DIV5. Quantification of total dendritic length (B1) and branching point number (B2) at DIV3 (n=567, 215 and 303 HET, HOM and WT respectively), at DIV4 (n=551, 272 and 342 HET, HOM and WT respectively) and at DIV5 (n=306, 343 and 579 HET, HOM and WT respectively). Transfection with exogenous Disc1 did not affect dendritic length (B1) and branching points (B2) DIV3 (n=436 and 284 respectively), DIV4 (n=538 and 301 respectively) and at DIV5 (n=579 and 429 respectively). (Dendritic length: p=2.9E−02 at DIV4 for HOM vs WT; Dendritic branching point: p=1.5E−03 and p=1.0E−02 at DIV4 for HET and HOM vs WT; p=2.7E−02 at DIV4 dor HOM vs HOM+Disc1). In some cases we observed an “over-rescue” in cells transfected with exogenous Disc1 (dendritic length: p=1.7E−02 at DIV5 for HOM+Disc1 vs WT).

C. Dendritic spines from WT, HET and HOM cortical neurons transfected at DIV8 with β-actin-GFP or β-actin-GFP+Disc1 construct and fixed at DIV22. Spine density (number of spines per 75μM of dendrite) was reduced in both HET and HOM neurons (n=19, 39 and 13 for HOM, HET and WT respectively) (p=4.7E−05 and p=2.6E−04 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively). Mushroom (p=1.5E−03 and p=8.2E−03 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively), stubby (p=4.9E−03 and p=4.8E−02 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively) and filopodia spines (p=1.6E−02 and p=7.5E−03 for HET and HOM vs WT, respectively) were all affected. Transfection with exogenous Disc1 rescued the phenotype in both HET and HOM mice (n=16 and 11, respectively) (p=2.2E−02 and p=4.0E−02 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1, respectively). Stubby spines (p=8.9E−03 and p=3.8E−03 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1, respectively) were rescued.

D. Mushroom spines displayed an increase in head-length but not in width in both HET and HOM neurons (D1, D2) (n=1025, 465 and 674 for HET, HOM and WT respectively). (p <1.0E−04 for HET and HOM vs WT). Transfection with exogenous Disc1 rescued the head-length phenotype in both HET and HOM neurons (D3, D4) (n=455 and 359, respectively) (p=3.0E−03 and p<1.0E−04 for HET and HOM vs HET+Disc1 and HOM+Disc1).

*p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.0005 against WT.

¤p<0.05; ¤¤p<0.005; ¤¤¤p<0.0005 against HET or HOM.

Notably, and despite the lack of effect on neurite growth, Disc1Tm1Kara results in alterations of dendritic spine density and size (Figure 4C, D). Specifically, analysis of dendritic spine development showed that total spine density was reduced in both HET and HOM cortical neurons at DIV22 compared to WT neurons (Figure 4C), with a significant reduction of all spine morphotypes. Morphometric analysis of mushroom spines showed again a small, but statistically significant increase in the head-length but not in the head-width (Figure 4D). The average spine head-length was increased by 21.6% in HET and 27.8% in HOM neurons compared to WT neurons. Complementation experiments confirmed that the reduction in spine density is a direct effect of reduced Disc1 levels, since both HET and HOM neurons transfected with Disc1-FL showed an almost complete restoration of spine size and density (Figure 4C, D).

Discussion

We have previously shown that a mouse Disc1 orthologue (Disc1Tm1Kara), genetically engineered to carry a gene-disruptive lesion, results in alterations of neuronal morphology (including dendritic arborization and spine development) that show a strong regional and cell type selectivity (Kvajo et al., 2008; Kvajo et al., 2011). Here we built upon these findings and provide a number of relevant and novel insights. First, we provide unequivocal evidence that this human risk allele alters neural growth and extension, as well as the dendritic spine formation not only in vivo but also in dissociated primary neurons, suggesting that the observed effects are to a large extent cell autonomous in nature. Interestingly, and as previously noted (Kvajo et al 2011), the extent of these deficits did not appreciably differ among heterozygous and homozygous neurons. The fact that Disc1Tm1Kara acts in a dominant fashion suggests that Disc1 is haploinsufficient and a single copy of the gene is incapable of producing sufficient protein to assure normal function. This observation furthers supports the relevance of Disc1Tm1Kara to the human pathology.

Importantly, we show a cell type-specific contribution of Disc1, with distinct effects on the development of hippocampal and cortical neurons. This effect likely reflects differential sensitivity of various neuronal subtypes to alterations in Disc1 levels and the corresponding affected signaling pathways (Kvajo et al., 2010). While hippocampal and cortical neurons share a large number of attributes (Spruston, 2008), they have individual identities with unique morphological and functional properties (Chen et al., 2005). Distinct pathways controlling dendrite outgrowth in cortical and hippocampal neurons have been reported (Ko et al., 2005; Kwon et al., 2011) although the mechanisms behind these differences are not yet well understood. In that respect, the differential effect of Disc1Tm1Kara may stem from the role of Disc1 in downstream signaling pathways such as cAMP-dependent signaling (Kvajo et al., 2011), which was shown to be differently modulated in cortical and hippocampal neurons (Dumuis et al., 1988; Miro et al., 2002).

Second, by comparing Disc1 protein localization in WT and mutant neurons we show that Disc1 consistently localizes to vesicular structures juxtaposed to the cis-Golgi network, suggesting that these may be vesicles associated with the trans-Golgi network (Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 2000). While we were not able to assign a specific cargo to the Disc1-positive vesicles (a wide range of molecules is transported via such structures), it is pertinent to discuss some possible roles of Disc1 within this cellular department. For example, Disc1 may sequester specific cargo molecules transported within the vesicles, through their association with its binding domains (Kvajo et al., 2010). Alternatively, it may regulate the cellular functions of the Golgi apparatus. Notably, the major downstream effector of cAMP, Protein Kinase A (PKA), regulates Golgi assembly and function in response to intracellular changes in cAMP (Mavillard et al., 2010; Bejarano et al., 2006). Moreover, phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) a major regulator of cAMP levels, which is decreased in Disc1 mutant mice (Kvajo et al., 2011), is also associated with the Golgi apparatus (Verde et al., 2001), raising the possibility that Disc1 may be part of macromolecular complexes regulating cAMP in this cellular compartment. Importantly, the Golgi apparatus and post-Golgi trafficking have critical roles in dendrite and axonal growth, and spine morphogenesis (Horton et al., 2005; Rosso et al., 2004; Camera et al., 2008). Thus, Disc1-mediated impairments in aspects of Golgi-related metabolism may adversely affect dendritic growth. It is interesting to note that BDNF, a major Golgi-derived regulator of dendritic growth (McAllister, 2000; Evans et al., 2011), differentially affects cortical and hippocampal neurons (Kwon et al., 2011) further demonstrating specialized responses to shared signaling pathways. In that respect it is also noteworthy that there are established links between the Golgi apparatus and neuronal phenotypes associated with 22q11.2 microdeletions, a well-established genetic risk factor for schizophrenia (Mukai et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2013).

Interestingly, and in contrast to earlier studies (Kirkpatrick et al., 2006; Hayashi-Takagi et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; Carlisle et al., 2011), we did not observe Disc1 immunoreactivity in the spine compartments of hippocampal or cortical neurons. The reasons for this discrepancy remain unknown but it is worth emphasizing here that we evaluated Disc1 cellular localization using antibodies of confirmed specificity, using Disc1 mutant mice as a negative control.

As a conclusion, this study provides evidence that the effects of the Disc1 mutation in neuronal cultures recapitulate to a large extent the in vivo phenotypes. While a complete comparison between the two systems is not possible, the observed changes support a role for Disc1 in axonal, dendritic and spine development. Thus, in vitro cultures derived from Disc1Tm1Kara mice provide a valuable model for future mechanistic analysis and identification of the cellular and biochemical effects of this mutation. In conjunction, this system can also serve as a platform for the development of pharmacological screens which will enhance the drug discovery efforts.

Material and methods

Animals and genotyping

We used mice of the C57BL6 strain and the Disc1Tm1Kara mutant mice (Koike et al., 2006). Genotypes were determined using genomic DNA and the PCR protocol and primers as previously described (Koike et al., 2006) All animal procedures were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Primary cell cultures and transfection

Primary culture cells were performed as described (Loe-Mie et al., 2010). Heterozygous Disc1Tm1Kara mice were crossed, resulting in embryos of all three genotypes. E15.5 Disc1Tm1Kara telencephalic neurons or E17.5 Disc1Tm1Kara hippocampal neurons were dissociated by individually dissecting each embryo out of its amniotic sac, removing the head and dissecting out the target brain tissue in an separate dish. The remainder of the brain was used for genotyping. Neurons from each embryo were dissociated enzymatically (0.25% trypsin, DNase), mechanically triturated with a flamed Pasteur pipette, and individually plated on 35mm dishes (8×105 cortical cells and 4×105 hippocampal cells per dish) coated with poly-DL-ornithine (Sigma), in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Four hours after plating, DMEM was replaced by Neurobasal® medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2mM glutamine and 2% B27 (Invitrogen). For dendritic analysis, primary neuronal cultures were transfected after two or seven days in culture and analyzed on day three, four and five or on day nine. To analyze dendritic spines, neurons were transfected after seven or eight days in culture and analyzed on day 21 or 22 respectively. Cells were transfected with constructs (co-transfections with Disc1-FL were performed at 1:4 ratio) using Lipofectamine and Plus-Reagent (Invitrogen), as described by the manufacturer.

For the analysis of neurite length and ramification and for spine numbers and length, cells were scanned using the laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM 510) at 40x magnification or 63x magnification (with a 2X digital zoom), respectively, and 3D Z-stacks were build using the ImageJ software (Wayne Rasband, NIH). All the analysis were carried out with the Wright Cell Imaging Facility plug-in in ImageJ. Neurite length was measured using the “freehand line sections” tool, and the spine length with the “straight line sections” tool. Spine numbers were manually counted on 75 μm long dendritic segments starting after the first branch point in the dendritic tree. One 75 μm dendritic segment per neuron was analyzed. They were categorized into filopodia, stubby and mushroom classes as described (Bourne and Harris, 2008). The dendritic spine length measurement consisted in measuring the neck of the mushroom spines.

Constructs

Mouse Disc1 cDNA was cloned as described (Kvajo et al., 2011). The β-actin-GFP expressing plasmid was described before (Mukai et al., 2004).

Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed by incubation for 20 min at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), permeabilized by incubation for 10 min at room temperature in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked for 30 min at RT with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, washed three times in PBS and incubated for 1h at room temperature with appropriate Alexa-coupled secondary antibodies (1:1000, Invitrogen) diluted in the blocking solution. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and mounted with Prolong Gold Mounting Medium (Invitrogen). The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-MAP2 (1:10,000, Abcam), mouse anti-Tau1 (1:500, Chemicon), purified rabbit anti-Disc1 directed against the N-terminal portion of the mouse Disc1 (1:100 (Koike et al., 2006)), rat anti-HA (1:100, Roche), mouse anti-GM130 (1:500, BD Biosciences), mouse anti-syntaxin 6 (1:100, Abcam), mouse anti-PSD-95 (1:100, Abcam), mouse anti-synaptophysin (1:100, Sigma), mouse anti-GFAP (1:200, Chemicon), mouse anti-Cytochrome C (1:1000, BD Biosciences), mouse anti-pericentrin (1:100, BD Biosciences), goat anti-PCM1 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), mouse anti-kinesin (1:100, Chemicon), goat anti-Grp78 (1:200 Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-Tfr (1:100, BD Biosciences), mouse anti-Rab11 (1:100, BD Biosciences), and mouse anti-Rab7 (1:100, Abcam). A second, alternative protocol has been used to stain for centrosome-associated proteins (Kamiya et al., 2008). Cells were fixed by incubation for 10 min on ice in −20 °C methanol, and blocked for 30 min at RT with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies (purified rabbit anti-Disc1 directed against the N-terminal portion of the mouse Disc1 (1:100), goat anti-PCM1 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), mouse anti-kinesin (1:100, Chemicon), mouse anti-pericentrin (1:100, BD Biosciences) in blocking solution, washed three times in PBS and incubated with appropriate Alexa-coupled secondary antibodies (1:1000, Invitrogen) diluted in the blocking solution. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and mounted with Prolong Gold Mounting Medium (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

The analyses performed on transgenic neurons with at least 5 embryos and at least 40 cells and 12 cells per genotype for dendrite and spine analyses respectively. T-test were performed with Excel Software and KS-test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) with web software (Kirkman, 2004) http://www.physics.csbsju.edu).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dionne Swor and Megan Sribour for technical help. This work was supported by grants MH77235 and MH080234 (to JAG) as well as partly funded by INSERM, the ANR 2011 ERNA-006-01 and Fondation Orange (MS). AMLB was supported in part by Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale and Fondation Bettencourt-Schueller. MK was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arguello PA, Gogos JA. Modeling madness in mice: one piece at a time. Neuron. 2006;52:179–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arguello PA, Gogos JA. Genetic and cognitive windows into circuit mechanisms of psychiatric disease. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arguello PA, Markx S, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Development of animal models for schizophrenia. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:22–26. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bejarano E, Cabrera M, Vega L, Hidalgo J, Velasco A. Golgi structural stability and biogenesis depend on associated PKA activity. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3764–3775. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne JN, Harris KM. Balancing structure and function at hippocampal dendritic spines. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:47–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandon NJ, Schurov I, Camargo LM, Handford EJ, Duran-Jimeniz B, Hunt P, Millar JK, Porteous DJ, Shearman MS, Whiting PJ. Subcellular targeting of DISC1 is dependent on a domain independent from the Nudel binding site. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camera P, Schubert V, Pellegrino M, Berto G, Vercelli A, Muzzi P, Hirsch E, Altruda F, Dotti CG, Di CF. The RhoA-associated protein Citron-N controls dendritic spine maintenance by interacting with spine-associated Golgi compartments. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:384–392. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlisle HJ, Luong TN, Medina-Marino A, Schenker L, Khorosheva E, Indersmitten T, Gunapala KM, Steele AD, O’Dell TJ, Patterson PH, Kennedy MB. Deletion of densin-180 results in abnormal behaviors associated with mental illness and reduces mGluR5 and DISC1 in the postsynaptic density fraction. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16194–16207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5877-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JG, Rasin MR, Kwan KY, Sestan N. Zfp312 is required for subcortical axonal projections and dendritic morphology of deep-layer pyramidal neurons of the cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17792–17797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509032102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapcote SJ, Lipina TV, Millar JK, Mackie S, Christie S, Ogawa F, Lerch JP, Trimble K, Uchiyama M, Sakuraba Y, Kaneda H, Shiroishi T, Houslay MD, Henkelman RM, Sled JG, Gondo Y, Porteous DJ, Roder JC. Behavioral phenotypes of Disc1 missense mutations in mice. Neuron. 2007;54:387–402. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumuis A, Sebben M, Bockaert J. Pharmacology of 5-hydroxytryptamine-1A receptors which inhibit cAMP production in hippocampal and cortical neurons in primary culture. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;33:178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans SF, Irmady K, Ostrow K, Kim T, Nykjaer A, Saftig P, Blobel C, Hempstead BL. Neuronal brain-derived neurotrophic factor is synthesized in excess, with levels regulated by sortilin-mediated trafficking and lysosomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29556–29567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi-Takagi A, Takaki M, Graziane N, Seshadri S, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Makino Y, Seshadri AJ, Ishizuka K, Srivastava DP, Xie Z, Baraban JM, Houslay MD, Tomoda T, Brandon NJ, Kamiya A, Yan Z, Penzes P, Sawa A. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) regulates spines of the glutamate synapse via Rac1. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nn.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hikida T, Jaaro-Peled H, Seshadri S, Oishi K, Hookway C, Kong S, Wu D, Xue R, Andrade M, Tankou S, Mori S, Gallagher M, Ishizuka K, Pletnikov M, Kida S, Sawa A. Dominant-negative DISC1 transgenic mice display schizophrenia-associated phenotypes detected by measures translatable to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14501–14506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton AC, Racz B, Monson EE, Lin AL, Weinberg RJ, Ehlers MD. Polarized secretory trafficking directs cargo for asymmetric dendrite growth and morphogenesis. Neuron. 2005;48:757–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James R, Adams RR, Christie S, Buchanan SR, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) is a multicompartmentalized protein that predominantly localizes to mitochondria. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiya A, Tan PL, Kubo K, Engelhard C, Ishizuka K, Kubo A, Tsukita S, Pulver AE, Nakajima K, Cascella NG, Katsanis N, Sawa A. Recruitment of PCM1 to the centrosome by the cooperative action of DISC1 and BBS4: a candidate for psychiatric illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:996–1006. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkman TW. Statistics To Use. 2004;2008 Ref Type: Internet Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkpatrick B, Xu L, Cascella N, Ozeki Y, Sawa A, Roberts RC. DISC1 immunoreactivity at the light and ultrastructural level in the human neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:436–450. doi: 10.1002/cne.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko M, Zou K, Minagawa H, Yu W, Gong JS, Yanagisawa K, Michikawa M. Cholesterol-mediated neurite outgrowth is differently regulated between cortical and hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42759–42765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koike H, Arguello PA, Kvajo M, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Disc1 is mutated in the 129S6/SvEv strain and modulates working memory in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3693–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511189103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda K, Yamada S, Tanaka M, Iizuka M, Yano H, Mori D, Tsuboi D, Nishioka T, Namba T, Iizuka Y, Kubota S, Nagai T, Ibi D, Wang R, Enomoto A, Isotani-Sakakibara M, Asai N, Kimura K, Kiyonari H, Abe T, Mizoguchi A, Sokabe M, Takahashi M, Yamada K, Kaibuchi K. Behavioral alterations associated with targeted disruption of exons 2 and 3 of the Disc1 gene in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4666–4683. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kvajo M, McKellar H, Arguello PA, Drew LJ, Moore H, Macdermott AB, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. A mutation in mouse Disc1 that models a schizophrenia risk allele leads to specific alterations in neuronal architecture and cognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7076–7081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802615105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kvajo M, McKellar H, Drew LJ, Lepagnol-Bestel AM, Xiao L, Levy RJ, Blazeski R, Arguello PA, Lacefield CO, Mason CA, Simonneau M, O’donnell JM, Macdermott AB, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Altered axonal targeting and short-term plasticity in the hippocampus of Disc1 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kvajo M, McKellar H, Gogos JA. Molecules, signaling, and schizophrenia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:629–656. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon M, Fernandez JR, Zegarek GF, Lo SB, Firestein BL. BDNF-promoted increases in proximal dendrites occur via CREB-dependent transcriptional regulation of cypin. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9735–9745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6785-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Zhou Y, Jentsch JD, Brown RA, Tian X, Ehninger D, Hennah W, Peltonen L, Lonnqvist J, Huttunen MO, Kaprio J, Trachtenberg JT, Silva AJ, Cannon TD. Specific developmental disruption of disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 function results in schizophrenia-related phenotypes in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18280–18285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Roberts TH, Hirschberg K. Secretory protein trafficking and organelle dynamics in living cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:557–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mavillard F, Hidalgo J, Megias D, Levitsky KL, Velasco A. PKA-mediated Golgi remodeling during cAMP signal transmission. Traffic. 2010;11:90–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAllister AK. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of dendrite growth. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:963–973. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Millar JK, Wilson-Annan JC, Anderson S, Christie S, Taylor MS, Semple CA, Devon RS, Clair DM, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH, Porteous DJ. Disruption of two novel genes by a translocation co-segregating with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1415–1423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miro X, Perez-Torres S, Artigas F, Puigdomenech P, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Regulation of cAMP phosphodiesterase mRNAs expression in rat brain by acute and chronic fluoxetine treatment. An in situ hybridization study. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:1148–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris JA, Kandpal G, Ma L, Austin CP. DISC1 (Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1) is a centrosome-associated protein that interacts with MAP1A, MIPT3, ATF4/5 and NUDEL: regulation and loss of interaction with mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1591–1608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukai J, Dhilla A, Drew LJ, Stark KL, Cao L, Macdermott AB, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Palmitoylation-dependent neurodevelopmental deficits in a mouse model of 22q11 microdeletion. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1302–1310. doi: 10.1038/nn.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukai J, Liu H, Burt RA, Swor DE, Lai WS, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Evidence that the gene encoding ZDHHC8 contributes to the risk of schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:725–731. doi: 10.1038/ng1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozeki Y, Tomoda T, Kleiderlein J, Kamiya A, Bord L, Fujii K, Okawa M, Yamada N, Hatten ME, Snyder SH, Ross CA, Sawa A. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1 (DISC-1): mutant truncation prevents binding to NudE-like (NUDEL) and inhibits neurite outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:289–294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pletnikov MV, Ayhan Y, Nikolskaia O, Xu Y, Ovanesov MV, Huang H, Mori S, Moran TH, Ross CA. Inducible expression of mutant human DISC1 in mice is associated with brain and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:173–186. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Murillo L, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. The genetic architecture of schizophrenia: new mutations and emerging paradigms. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:63–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-072010-091100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosso S, Bollati F, Bisbal M, Peretti D, Sumi T, Nakamura T, Quiroga S, Ferreira A, Caceres A. LIMK1 regulates Golgi dynamics, traffic of Golgi-derived vesicles, and process extension in primary cultured neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3433–3449. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawamura N, Sawamura-Yamamoto T, Ozeki Y, Ross CA, Sawa A. A form of DISC1 enriched in nucleus: altered subcellular distribution in orbitofrontal cortex in psychosis and substance/alcohol abuse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406543102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen S, Lang B, Nakamoto C, Zhang F, Pu J, Kuan SL, Chatzi C, He S, Mackie I, Brandon NJ, Marquis KL, Day M, Hurko O, McCaig CD, Riedel G, St CD. Schizophrenia-related neural and behavioral phenotypes in transgenic mice expressing truncated Disc1. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10893–10904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shoji H, Toyama K, Takamiya Y, Wakana S, Gondo Y, Miyakawa T. Comprehensive behavioral analysis of ENU-induced Disc1-Q31L and -L100P mutant mice. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:108. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spruston N. Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:206–221. doi: 10.1038/nrn2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taya S, Shinoda T, Tsuboi D, Asaki J, Nagai K, Hikita T, Kuroda S, Kuroda K, Shimizu M, Hirotsune S, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. DISC1 regulates the transport of the NUDEL/LIS1/14-3-3epsilon complex through kinesin-1. J Neurosci. 2007;27:15–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3826-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verde I, Pahlke G, Salanova M, Zhang G, Wang S, Coletti D, Onuffer J, Jin SL, Conti M. Myomegalin is a novel protein of the golgi/centrosome that interacts with a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11189–11198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Q, Brandon NJ. Regulation of the cytoskeleton by Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Q, Charych EI, Pulito VL, Lee JB, Graziane NM, Crozier RA, Revilla-Sanchez R, Kelly MP, Dunlop AJ, Murdoch H, Taylor N, Xie Y, Pausch M, Hayashi-Takagi A, Ishizuka K, Seshadri S, Bates B, Kariya K, Sawa A, Weinberg RJ, Moss SJ, Houslay MD, Yan Z, Brandon NJ. The psychiatric disease risk factors DISC1 and TNIK interact to regulate synapse composition and function. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:1006–1023. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu B, Hsu PK, Stark KL, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Derepression of a Neuronal Inhibitor due to miRNA Dysregulation in a Schizophrenia-Related Microdeletion. Cell. 2013;152:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu B, Ionita-Laza I, Roos JL, Boone B, Woodrick S, Sun Y, Levy S, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. De novo gene mutations highlight patterns of genetic and neural complexity in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/ng.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu B, Roos JL, Dexheimer P, Boone B, Plummer B, Levy S, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Exome sequencing supports a de novo mutational paradigm for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:864–868. doi: 10.1038/ng.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu B, Roos JL, Levy S, van Rensburg EJ, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:880–885. doi: 10.1038/ng.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.