Abstract

The signaling pathway mediated by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) participates in various biologic processes, including cell growth, differentiation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling. In the context of cancer, TGF-β signaling can inhibit tumor growth in early-stage tumors. However, in late-stage tumors, the very same pathway promotes tumor invasiveness and metastasis. This paradoxical effect is mediated through similar to mothers against decapentaplegic or Smad protein dependent and independent mechanisms and provides an opportunity for targeted cancer therapy. This review summarizes the molecular process of TGF-β signaling and the changes in inhibitory Smads that contribute to lung cancer progression. We also present current approaches for rational therapies that target the TGF-β signaling pathway in cancer.

Keywords: TGF-β signaling, Smads, Non-small cell lung cancer survival, Target-based therapy

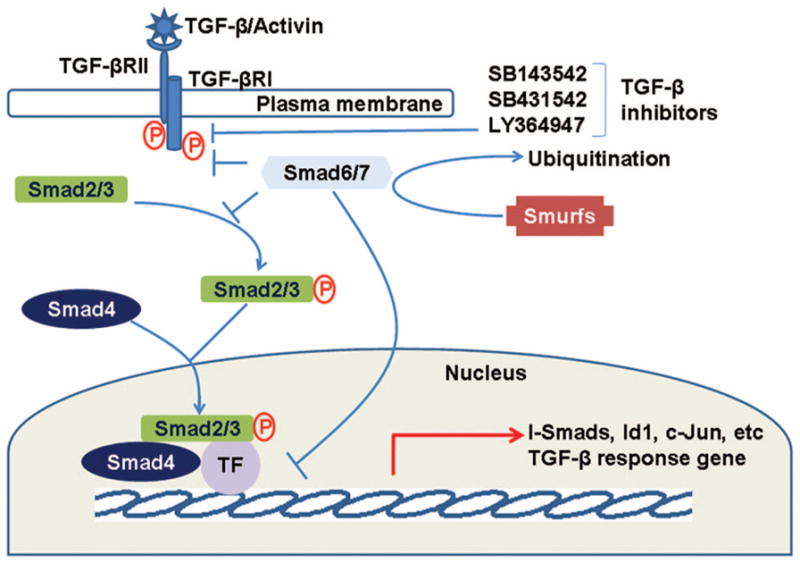

Transforming growth factor (TGF-β) belongs to a superfamily of structurally related polypeptides that also includes TGF-β2, TGF-β3, Activins, Nodals, and bone morphogenetic (BMP) proteins.1,2 TGF-β receptor I (TGF-β RI) is recruited to the complex by ligand binding to a heteromeric complex of type I and type II (TGF-β RII) receptors, which are serine/threonine kinase transmembrane proteins. This results in the activation of TGF-β RII kinase domain in the cytoplasm and then phosphorylates receptor-regulated Smad proteins (R-Smad), Smad2 and Smad3. Activated phospho-Smad2 and 3 bind with common mediated Smad (co-Smad), Smad4, and translocate to the nucleus, which in turn regulates transcription in a diverse array of genes (Figure 1).3 TGF-β signaling is subjected to negative feedback by two inhibitory Smads (I-Smad), Smad6 and Smad7. Both I-Smads can interfere the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 by interaction with TGF-β RI.4,5 The termination of TGF-β signaling can also be achieved through ubiquitination of TGF-β RI and I-Smads by ubiquitin ligases Smad ubiquitin regulatory factors 1 and 2 (Smurf1 and Smurf2), which promote polyubiquitination followed by lysosomal-mediated degradation (Figure 1).6 In addition to Smads mediated signaling, TGF-β can also activate Smad-independent pathways in different cell contexts.7,8

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling pathway. TGF-β signaling is initiated by the binding of TGF-β to its receptors, transforming growth factor-β receptor I (TGF-β RI) and transforming growth factor-β receptor II (TGF-β RII), and receptor tyrosine kinase activation which then phosphorylates Smad2/3. Activated Smad2/3 regulates gene expression of Smad4 and other transcription factors (TF). Feedback regulation is mediated by Smad6/7, which interferes the binding of Smad2/3 to TGF-β receptors and inhibits transcription. Both Smad6 and Smad7 are in turn induced by TGF-β and regulated by Smad ubiquitin regulatory factors (Smurfs). Synthetic inhibitors inactivate the TGF-β pathway by inhibition of receptor enzymatic activity.

TGF-β and Cancer

Alterations in TGF-β signaling are linked to a variety of human diseases, including cancer and inflammation. Disruption of TGF-β homeostasis occurs in several human cancers.9,10 Data from both experimental model systems and studies of human cancers clearly show that not only the ligand itself but also its downstream elements, including its receptors and its primary cytoplasmic signal transducers, the Smad proteins, are important in suppressing primary tumorigenesis in many tissue types.11 However, many human cancers, including lung cancer, often overexpress TGF-β. Furthermore, TGF-β enhances the invasiveness and meta-static potential in certain late-stage tumors.12 The role of TGF-β in cancer progression and metastasis is generally accompanied by decreased or altered TGF-β responsiveness and increased expression or activation of the TGF-β ligand.12 In the immunocytochemical analysis, localization of secreted TGF-β is found at the advancing edges of primary tumors and in lymph node metastases of human mammary carcinoma.13 High levels of TGF-β were also detected in the serum of patients with lung cancer and colorectal carcinomas compared with nondiseased individuals, and TGF-β level in serum is deceased to normal range after surgical resection of the tumor in colorectal cancer.14,15 This suggests that both autocrine and paracrine effects of TGF-β contribute to promote tumor progression.

Although most lung cancer cells secrete TGF-β, the malignant transformation in lung cancer results in a loss of the tumor suppressor effects of TGF-β. Loss of the TGF-β response, which results in lost of inhibitory effect of TGF-β on proliferation, has been associated with tumor development and/or tumor progression in several cancers.16,17 Reduced expression and inactivation of TGF-β receptors were associated with loss of sensitivity with antiproliferative effects of TGF-β in carcinogenesis.11 In lung cancer, overexpression of TGF-β is associated with better prognosis in 5-year patient survival.18 TGF-β1 level in serum was elevated after radiotherapy in lung cancer, and the risk of radiation-induced lung injury is associated with TGF-β1 single nucleotide polymorphism.19,20

I-Smads and TGF-β Signaling

The feedback mechanisms that regulate TGF-β signaling play a central role in cellular homeostasis mediated by TGF-β (Figure 1). The transcriptional activation of I-Smads is induced by TGF-β and other signaling pathways such as EGF, interferon gamma, and interleukin 1β.21–23 I-Smads (Smad6 and Smad7) regulate TGF-β function by interfering with receptor-mediated phosphorylation of Smad2/3.5,24 Generally, Smad6 is thought to repress BMP signaling, whereas Smad7 represses the TGF-β signaling pathway.21 However, both proteins can regulate the TGF-β signaling pathway through negative regulation in lung epithelial cells.25 In lung cancer, Smad6 is overexpressed in a portion of the tumors, and high expression of Smad6 is associated with poor survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer.26 Knockdown of Smad6 in overexpressed lung cancer cells induced apoptosis and growth arrest at the G1 phase, which contributed to the reestablishment of TGF-β homeostasis in lung cancer cells by reactivating the TGF-β signal pathway.26 Similarly, overexpression of Smad7 causes malignant conversion in multistage cancer models by cooperating with oncogenic Ras and enhances tumorigenicity in pancreatic cancer.27,28 Furthermore, stable expression of Smad7 impairs bone metastasis in human melanoma cells and lung and liver metastasis in JygMC(A) breast cancer cells.29,30 These studies indicate that I-Smads play a critical role in tumorigenesis by regulating TGF-β homeostasis in normal and cancer cells. Therapies targeting I-Smads could potentially help re-establish TGF-β mediated growth inhibition in tumors and enhance patient survival.

Development of TGF-β Signaling Inhibitors for Cancer Treatment

TGF-β suppresses early epithelial cancers by TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition. As premalignant lesions progress, TGF-β signaling contributes to tumor progression by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), thereby promoting the conversion of early epithelial tumors to invasive, metastatic tumors.31 Many inhibitors of TGF-β signaling target the EMT process. For example, the small molecule ATP competitive compounds SB-505124 and SB-431542 have been developed as inhibitors against the enzymatic activity of the TGF-β RI type receptor called activin receptor-like kinase ALK5.32–34 These drugs have been shown to inhibit TGF-β-induced cell migration and invasiveness in glioma or EMT in vitro.

In addition to small molecules, antibodies have been developed. The TGF-β antibody inhibits phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT activity in mammary cancer cells by neutralizing TGF-β protein and suppresses the growth of renal cell carcinoma overexpressing TGF-β.35,36 Antisense oligonucleotides have been developed to directly target TGF-β2 mRNA. Recently, targeted TGF-β2 suppression using AP 12009 has emerged as a promising novel approach for treating malignant gliomas and other highly aggressive TGF-β2-overexpressing tumors.37 Little studies have been done targeting TGF-β signaling pathway in lung cancer. However, our recent study suggests that Smad6 protein contributes to lung cancer survival and targeting Smad6 may serve as an effective means to reduce tumor growth and improve patient outcome.26

CONCLUSION

TGF-β signaling contributes to diverse cellular processes and plays a critical role in lung cancer growth and progression. TGF-β generally serves as a negative growth regulator in normal cells and early stage tumor development, but it promotes tumor invasiveness and metastases by inducing EMT and neoangiogenesis. Current strategies focus on developing effective therapies that target mainly the tumor-promoting activities of TGF-β signaling. However, the complex nature and dual effects of TGF-β signaling in cancer must be considered together to be effective in clinical trials for cancer therapy. This requires combinational therapies that seek to interfere with both TGF-β/Smads dependent- and independent-signaling processes.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the national R&D Program for Cancer Control Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (0720550-2) and the Brain Korea 21 Project (to H.S.J.) and by Research Funds from the Mayo Cancer Center and the Mayo Center for Individualized Medicine (to J.J.).

The authors thank Ms. Stacy Johnson for manuscript editing.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato Y, Habas R, Katsuyama Y, et al. A component of the ARC/Mediator complex required for TGF beta/Nodal signalling. Nature. 2002;418:641– 646. doi: 10.1038/nature00969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts AB. TGF-beta signaling from receptors to the nucleus. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1265–1273. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi H, Abdollah S, Qiu Y, et al. The MAD-related protein Smad7 associates with the TGFbeta receptor and functions as an antagonist of TGFbeta signaling. Cell. 1997;89:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imamura T, Takase M, Nishihara A, et al. Smad6 inhibits signalling by the TGF-beta superfamily. Nature. 1997;389:622– 626. doi: 10.1038/39355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebisawa T, Fukuchi M, Murakami G, et al. Smurf1 interacts with transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor through Smad7 and induces receptor degradation. J Biol Chem. 2001;20:12477–12480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signaling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Non-Smad TGF-beta signals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3573–3584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Caestecker MP, Piek E, Roberts AB. Role of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1388–1402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.17.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markowitz SD, Roberts AB. Tumor suppressor activity of the TGF-beta pathway in human cancers. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:93–102. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts AB, Wakefield LM. The two faces of transforming growth factor beta in carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8621–8623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalal BI, Keown PA, Greenberg AH. Immunocytochemical localization of secreted transforming growth factor-beta 1 to the advancing edges of primary tumors and to lymph node metastases of human mammary carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:381–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa Y, Takanashi S, Kanehira Y, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1 level correlates with angiogenesis, tumor progression, and prognosis in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shim KS, Kim KH, Han WS, et al. Elevated serum levels of transforming growth factor-beta1 in patients with colorectal carcinoma: its association with tumor progression and its significant decrease after curative surgical resection. Cancer. 1999;85:554–561. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<554::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SJ, Im YH, Markowitz SD, et al. Molecular mechanisms of inactivation of TGF-beta receptors during carcinogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanagisawa K, Osada H, Masuda A, et al. Induction of apoptosis by Smad3 and down-regulation of Smad3 expression in response to TGF-beta in human normal lung epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1998;17:1743–1747. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue T, Ishida T, Takenoyama M, et al. The relationship between the immunodetection of transforming growth factor-beta in lung adenocarcinoma and longer survival rates. Surg Oncol. 1995;4:51–57. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(10)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L, Wang L, Ji W, et al. Elevation of plasma TGF-beta1 during radiation therapy predicts radiation-induced lung toxicity in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a combined analysis from Beijing and Michigan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan X, Liao Z, Liu Z, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism at rs1982073:T869C of the TGFbeta1 gene is associated with the risk of radiation pneumonitis in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with definitive radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3370–3378. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afrakhte M, Moren A, Jossan S, et al. Induction of inhibitory Smad6 and Smad7 mRNA by TGF-beta family members. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:505–511. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulloa L, Doody J, Massague J. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta/SMAD signalling by the interferon-gamma/STAT pathway. Nature. 1999;397:710–713. doi: 10.1038/17826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Liang D, et al. A mechanism of suppression of TGF-beta/SMAD signaling by NF-kappa B/RelA. Genes Dev. 2000;14:187–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Moren A, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631– 635. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masui T, Wakefield LM, Lechner JF, et al. Type beta transforming growth factor is the primary differentiation-inducing serum factor for normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2438–2442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeon HS, Dracheva T, Yang SH, et al. SMAD6 contributes to patient survival in non-small cell lung cancer and its knockdown reestablishes TGF-beta homeostasis in lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9686–9692. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Lee J, Cooley M, et al. Smad7 but not Smad6 cooperates with oncogenic ras to cause malignant conversion in a mouse model for squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7760–7768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleeff J, Ishiwata T, Maruyama H, et al. The TGF-beta signaling inhibitor Smad7 enhances tumorigenicity in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:5363–5372. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javelaud D, Mohammad KS, McKenna CR, et al. Stable overexpression of Smad7 in human melanoma cells impairs bone metastasis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2317–2324. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma H, Ehata S, Miyazaki H, et al. Effect of Smad7 expression on metastasis of mouse mammary carcinoma JygMC(A) cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1734–1746. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442– 454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DaCosta Byfield S, Major C, Laping NJ, et al. SB-505124 is a selective inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta type I receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:744–752. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Callahan JF, et al. SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-β superfamily type I activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ge R, Rajeev V, Subramanian G, et al. Selective inhibitors of type I receptor kinase block cellular transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36803–36810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ananth S, Knebelmann B, Gruning W, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 is a target for the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor and a critical growth factor for clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2210–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hau P, Jachimczak P, Schlingensiepen R, et al. Inhibition of TGF-beta2 with AP 12009 in recurrent malignant gliomas: from preclinical to phase I/II studies. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:201–212. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]