Abstract

Aims

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) represents the deposition of amyloid β protein (Aβ) in the meningeal and intracerebral vessels. It is often observed as an accompanying lesion of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or in the brain of elderly individuals even in the absence of dementia. CAA is largely age-dependent. In subjects with severe CAA a higher frequency of vascular lesions has been reported. The goal of our study was to define the frequency and distribution of CAA in a one-year autopsy population (91 cases) from the Department of Internal Medicine, Rehabilitation, and Geriatrics, Geneva.

Materials and methods

Five brain regions were examined, including the hippocampus, and the inferior temporal, frontal, parietal, and occipital cortex, using an antibody against Aβ, and simultaneously assessing the severity of AD-type pathology with Braak stages for neurofibrillary tangles identified with an anti-tau antibody. In parallel, the relationships of CAA with vascular brain lesions were established.

Results

CAA was present in 53.8% of the studied population, even in cases without AD (50.6%). The strongest correlation was seen between CAA and age, followed by the severity of amyloid plaques deposition. Microinfarcts were more frequent in cases with CAA; however, our results did not confirm a correlation between these parameters.

Conclusion

The present data show that CAA plays a role in the development of microvascular lesions in the aging brain, but cannot be considered as the most important factor in this vascular pathology, suggesting that other mechanisms also contributes importantly to the pathogenesis of microvascular changes.

Keywords: amyloid angiopathy, cortical microinfarcts, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, neuropathology, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is defined as the deposition of amyloid β protein (Aβ) in the wall of meningeal as well as intracerebral vessels, in small- and medium-sized arteries, arterioles, and less frequently capillaries and small veins [1, 2]. It is a primary lesion in rare familial forms of CAA (for review see [3–5]), and it is more often seen sporadically, as an accompanying lesion of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and in the brain of elderly individuals even in the absence of age-related cognitive deficits. Based on autopsy series, the prevalence of CAA stands between 10 and 57% in the general population [6–11] and is substantially higher (about 80%) in AD brains [2, 12–14]. However, severe CAA was observed in only 21% in a large series of elderly cases [15], and even in AD, moderate to severe CAA has been reported in only 20.2–25.6% of cases [12, 16]. In fact, CAA could be considered as one of the manifestations of amyloidosis in the elderly [17].

Usually CAA affects leptomeningeal and small cerebral arteries and arterioles [3, 5], affected meningeal vessels generally outnumbering affected cerebral vessels. Aβ deposition begins in the vessel wall in the tunica media, around smooth muscle cells [18] and later invades the whole vessel wall. To define the severity of CAA on neuropathological examination, two different staging systems have been proposed. Vonsattel et al. [10] developed a useful three-stage scoring approach, and Olichney et al. [19] a 5-level grading system, based on the severity of Aβ deposition in the vessels. Interestingly, endothelial cells are preserved even in severe CAA [20].

Thal et al. distinguished two main subtypes of CAA depending on which vessels are affected [17]. In type 1 amyloid deposition appears also in the wall of capillaries besides arteries and/or veins, but is absent in type 2. Capillary CAA seems to be a distinct form of CAA [21], for which apolipoprotein E ε4 allele frequency is very high [17]. It occurs in any stage of CAA and it is correlated with the severity of AD pathology [1].

With advanced age, the severity, extent, and prevalence of CAA increase [6–10, 12, 22, 23]. The observation that CAA favours posterior brain regions has been well known for a long time [24]. The predilection sites of CAA due to Aβ deposition are the occipital, following by other neocortical (parietal, frontal, and temporal) areas, while the medial temporal structures and hippocampus are often spared or less affected [17]. CAA is rarely present in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum, and usually does not occur in the white matter and brainstem [12, 20, 25]; however Pantelakis reported a relatively high involvement (42.3 %) of the cerebellum [24], a value comparable to that observed in the hippocampus.

Mandybur [26] discussed “CAA-associated vasculopathies” as vascular alterations that could be associated with haemorrhages or infarcts. He distinguished seven types: the glomerular formation due to multiple arteriolar lumina, aneurysmal formations, obliterative intimal thickening, the “double-barreling” or concentric vessels-within-a-vessel configuration, perivascular or transmural chronic infiltration, hyaline degeneration and fibrinoid necrosis. The relationships between CAA and vascular lesions of the brain (as cortical microinfarcts, brain haemorrhagse, or microbleeds) are largely debated and most studies – with only rare exceptions [7, 10, 12, 22, 27] - confirm a correlation between amyloid angiopathy and vascular brain lesions [7, 28–35]. The aim of our study was to assess the frequency of CAA in a large cohort of autopsy materials, and to define its relation with vascular brain lesions and AD-type histopathological hallmarks.

Materials and methods

Ninety-one human brains corresponding to one calendar year (2007) of unselected autopsy materials were investigated in this study. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. The mean age (± S.D.) of the subjects was 78.2 ± 11.0 years (range, 45 to 97 years). The brains from and 46 women and 45 men were included in the study. In all cases routine macroscopic and microscopic neuropathological examination was performed to obtain final neuropathological diagnosis. All protocols for postmortem brain collection and use of clinical information were approved by the relevant ethical committee on research on human subjects at the University of Geneva School of Medicine. For the present study, tissue blocks from the hippocampus, inferior temporal cortex (Brodmann area 20, frontal cortex (Brodmann area 9), parietal cortex (Brodmann area 40), and occipital cortex (Brodmann areas 17 and 18 were obtained and embedded in paraffin. From each block, 14-µm-thick serial sections were stained with haematoxylin-eosin (HE), and with anti-tau (AT8; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA, 1:1,000), and anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies (4G8; Signet Laboratories, Dedham, MA, USA, 1:2,000), consecutively. Tissues were incubated overnight at 4°C. After incubation, sections were processed by the PAP method with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen [36].

Table 1.

Demographic data of the present series

| Number of cases (W/M) | Mean age ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (W/M) | 91 (46/45) | 78.2 ± 11.0 |

| Dementia | 32 (17/15) | 83.0 ± 9.1 |

| Non demented | 59 (29/30) | 75.6 ± 11.1 |

| AD* | 10 (5/5) | 84.4 ± 4.1 |

AD* = number of neuropathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease cases (Braak stage ≥ 4) M, men; W, women.

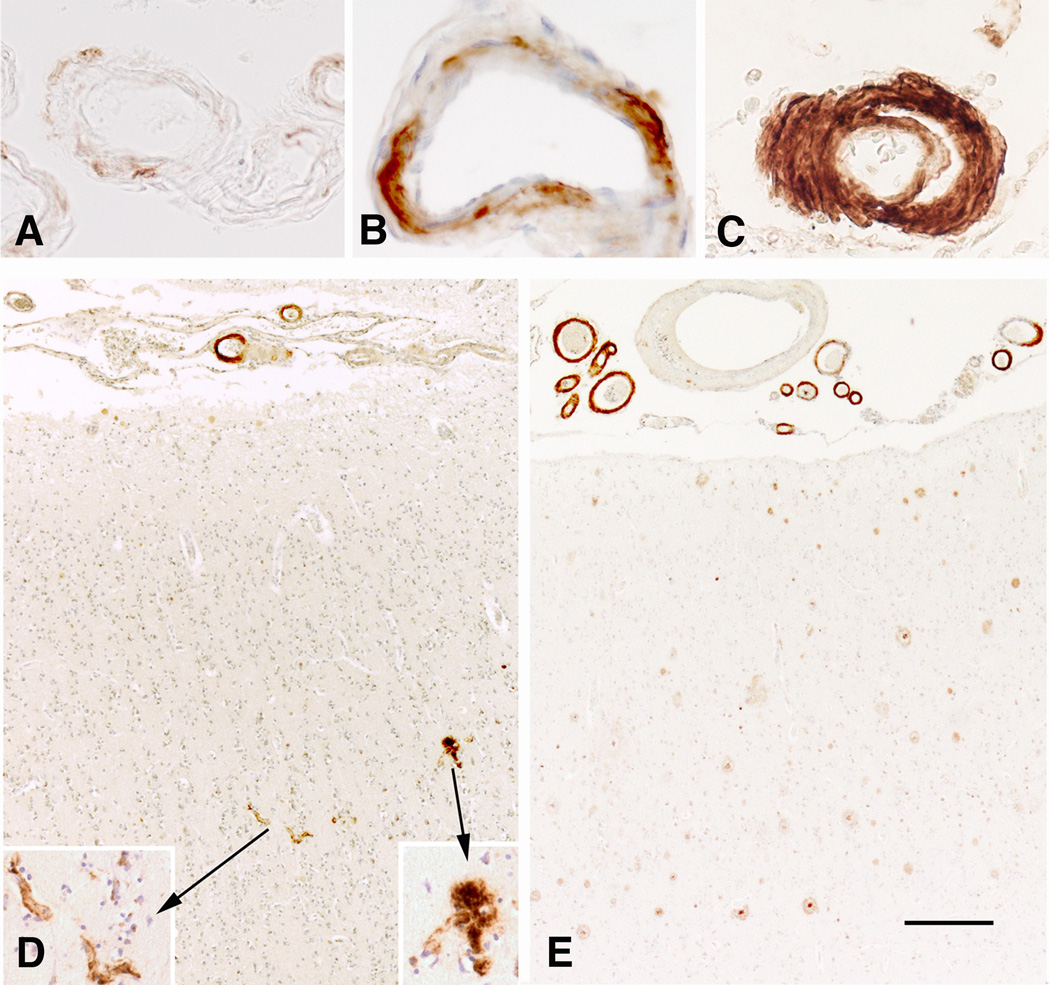

The presence or absence of meningeal and intracerebral amyloid angiopathy, as well as of capillary amyloid deposits was noted separately, in all five regions of interest. Furthermore, the severity of Aβ deposits in meningeal and intracerebral vessels was defined using the semiquantitative scale proposed by Vonsattel et al. [10] (Fig. 1A–C), in which “mild” stage corresponds to the presence of a thin rim of Aβ deposition in the media around smooth muscle cells but without their significant destruction. In “moderate” CAA, the media becomes thicker due to the deposition of fibrillary Aβ and a substantial loss of smooth muscle cells is present. In “severe” CAA, the vascular structure is destroyed and replaced by a large quantity of Aβ fibrils with focal fragmentation of the wall. In parallel, the number of cases with type 1 and type 2 CAA was noted (Fig. 1D–E). The severity of Aβ deposition varied in most cases within the same region, and as such, the dominant score was selected.

Figure 1.

Severity and types of CAA. (A) mild, (B) moderate, and (C) severe amyloid deposition in the meningeal vessels of the temporal lobe. (D) Type 1 with and (E) type 2 without amyloid deposition in capillaries in the frontal cortex in two different cases. Immunohistochemistry with anti-amyloid antibody 4G8 (A–E). Scale bar: 50 µm (A–C and inset); 200 µm (D and E).

To obtain the severity of AD-related pathologic changes, Braak stages for neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) were employed using an anti-tau antibody, according to the Braak and Braak criteria [37]. Demented cases were considered as having AD when their NFT Braak stage was at least 4. In parallel, on Aβ-immunostained slides, the Thal amyloid stages were obtained for amyloid plaques [38].

The number and location of cortical microinfarcts (CMI) was examined on HE-stained slides. The amount of microinfarcts was assessed using a semiquantitative 4-level scale (0–3) in each region, as published earlier, with the following scores: 0 (absence of lesions), 1 (<3 lesions per slide), 2 (3 to 5 lesions per slide), or 3 (>5 lesions per slide) [39]. Microinfarcts were defined as small cortical lesions seen only upon histological examination, composed of central gliotic tissue, newly formed capillary-type vessels, and at the periphery of variable amounts of glial cells (astrocytes and microglia) [27, 40, 41].

Statistical analyses employed group comparisons were conducted using Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test for continuous (ordinal) variables. Correlations were assessed using the non-parametric Spearman rank test. Maximal likelihood ordered logistic regression with proportional odds was used to evaluate sequentially the association between CMI in each region, Braak NFT staging, Aβ deposition staging (dependent variables), and the presence or absence of CAA in a univariate model. Subsequently, the same method was applied in a multivariate model to take into account the effect of age. All statistical analyses were done using Stata version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Prevalence, severity pattern, and extent of CAA

In this series of 91 autopsy cases, 49 (53.8%) displayed any one type or severity of CAA at least in one region, and all of them displayed meningeal CAA. Intracerebral CAA itself was less frequent, observed in 30 cases (32.9%). Moderate to severe CAA was found in neocortical regions to a lesser degree, ranging between 7.8% in the parietal cortex and 16.2% in the occipital cortex. In most cases intracerebral CAA appeared when meningeal vessels showed a moderate or severe degree of amyloid deposits.

Both meningeal and intracerebral amyloid angiopathy was most frequent in the occipital cortex, followed by the temporal, parietal, and frontal cortical areas, and the hippocampus (Table 2). Amyloid deposition in capillaries (type 1 CAA) was observed only in a relatively low percentage of cases (14.3%) in our series.

Table 2.

Distribution patterns of CAA in cortical regions

| Region | Meningeal CAA % |

Intracerebral CAA % |

|---|---|---|

| CA | 6.6 | 6.6 |

| TC | 32.9 | 15.4 |

| FC | 26.4 | 15.4 |

| PC | 26.6 | 16.6 |

| OC | 36.0 | 25.6 |

CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CA = hippocampus (Ammon’s horn), TC = temporal cortex, FC = frontal cortex, PC = parietal cortex, OC = occipital cortex

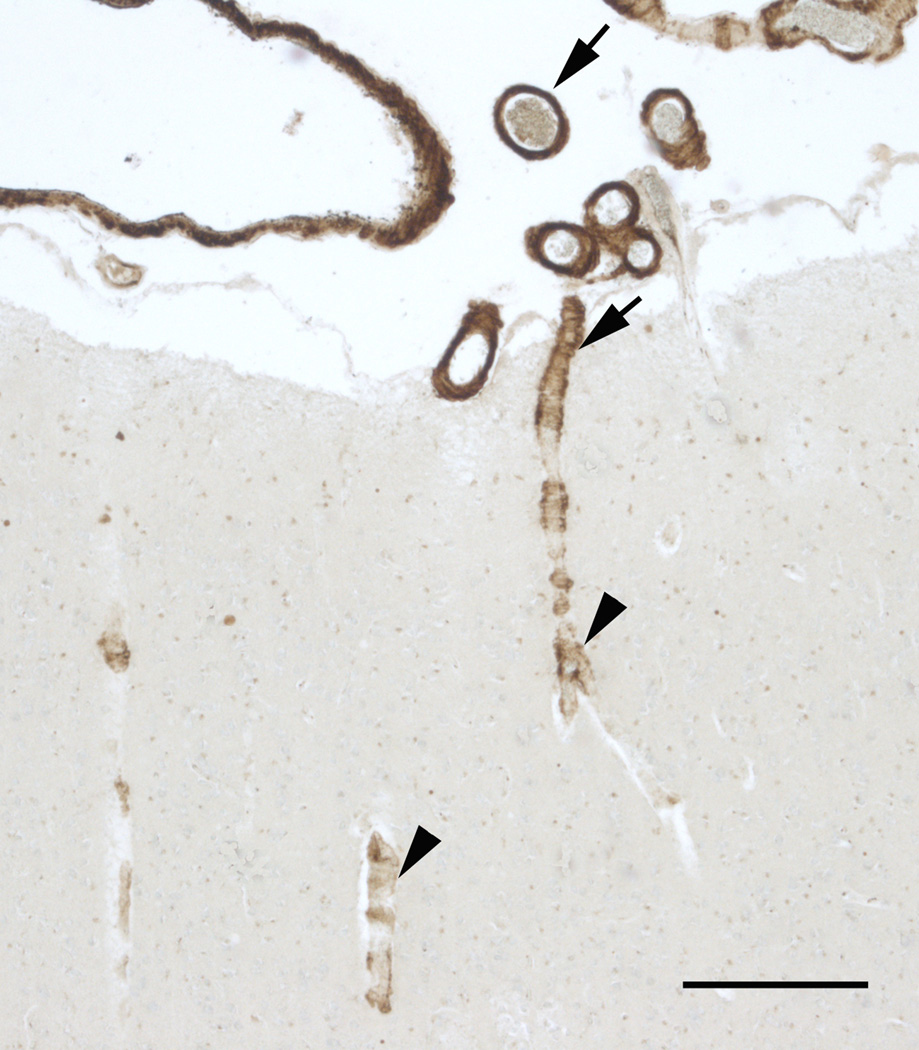

In addition, the amount of affected vessels paralleled the severity of amyloid deposition in the vessel wall. We observed a moderate, inverse statistically significant correlation between the severity of CAA and the laminar depth of the cortical pathology (Fig. 2), the superficial layers showing more severe amyloid deposition in the vessels than deeper layers (Spearman’s rho ranged between −0.326 and −0.454, p < 0.0001 for all regions).

Figure 2.

Example for the decreasing severity of CAA between superficial and deep layers in the frontal cortex. Note severe (arrows) CAA of the meningeal vessels and first cortical layer to contrast to the moderate-mild amyloid deposition (arrowheads) in deeper regions. Immunohistochemistry with anti-amyloid antibody 4G8. Scale bar: 200 µm.

Relation with advancing age

Data on effect of age on the prevalence of CAA are presented in Table 3. The percentage of CAA across increasing age groups rose from 16.6% (< 60 years) to 87.5% (> 90 years), in both controls and AD cases.

Table 3.

Prevalence of CAA in different age groups in the study sample

| Age group (years) |

% of cases with CAA |

% of cases with AD |

% of CAA in AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 – 59 | 16.6 % (1/6) | 0 % (0/6) | |

| 60 – 69 | 21.4 % (3/14) | 0 % (0/14) | |

| 70 – 79 | 44.4 % (8/18) | 0 % (0/18) | |

| 80 – 89 | 66.6 % (30/45) | 20.0 % (9/45) | 77.7 % (7/9) |

| 90 – 97 | 87.5 % (7/8) | 12.5 % (1/8) | 100 % (1/1) |

CAA and AD-type changes

There were 32 demented cases in the present series including 10 cases (31.2 %) corresponding neuropathologically to AD (Braak stage ≥ 4) (Table 1), 2 of which with associated cortical Lewy body pathology, 14 cases (43.8%) in which dementia could be explained by vascular lesions, 3 cases (9.4 %) diagnosed as pure Lewy body disease, 4 cases (12.5%) in which no neuropathological lesions were found to explain the clinical diagnosis of dementia, and 1 case (3.1%) in which brain metastases were found.

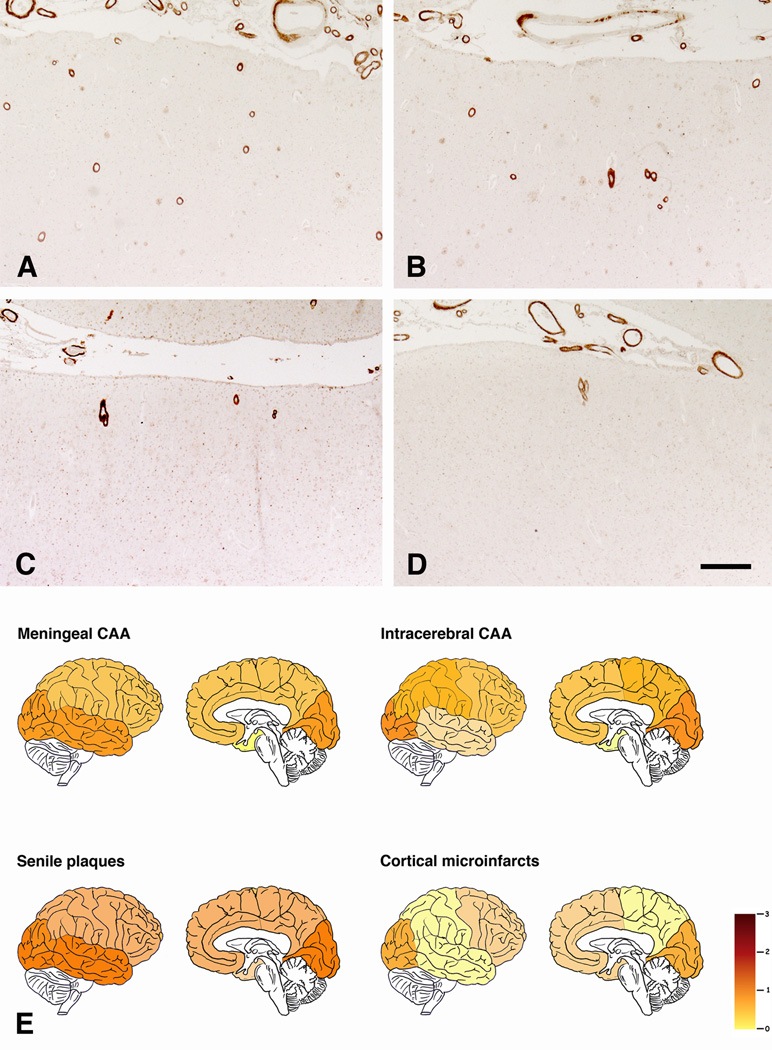

Amyloid plaques and CAA exhibited a comparable distribution. Both lesions were most numerous in the occipital and temporal cortex, followed by the frontal and parietal areas, and lastly by the hippocampus (Fig. 3A–E). However, among the 41 cases without CAA, 13 had amyloid plaques in at least one cortical region. In contrast, only 8 cases had CAA in any of the examined region in the absence of amyloid deposition.

Figure 3.

Representative examples of regional severity of CAA. Note severe involvement of occipital (A) and temporal (B) cortex in contrast to moderate severity in frontal (C) and parietal (D) cortex. (E) Schematic representation of regional differences in mean severity of meningeal and intracerebral CAA, amylid plaques, and CMI. Immunohistochemistry with anti-amyloid antibody 4G8 (A–D). Scale bar: (A–D): 400 µm.

The percentage of CAA-positive cases was higher in the neuropathologically confirmed AD group (80%) than in controls (50.6%), but without statistical difference (Fisher's exact test; p = 0.1). This non-significant difference persisted even when meningeal vessels and intracerebral amyloid vessel deposits were examined separately, (Fisher's exact test; p = 0.075). Interestingly, among AD-type lesions only amyloid plaques (p < 0.001) but not NFTs (p = 0.1) showed an association with CAA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relationship of CAA with vascular and Alzheimer-type lesions

| CAA + N (%) |

CAA − N (%) |

Fischer’s exact P < |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (N = 91) | 49 (53.8%) | 42 (46.2%) | |

| CMI | 21 (42.9%) | 13 (31.0%) | 0.282 |

| AD | 8 (16.3%) | 2 (4.8%) | 0.100 |

| SP | 41 (83.7%) | 11 (26.2%) | 0.001 |

CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CMI = cortical microinfarcts present, AD = neuropathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease (Braak stage ≥ 4), SP = senile plaques present

In the totality of our population 68.8% (22/32) of demented and 45.8% (27/59) of non-demented cases had CAA, and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.048). The majority of demented cases (78.6%, 11/15) with the pathological diagnosis of vascular encephalopathy (e.g., no other cause than vascular lesions was found to explain dementia clinically) showed CAA.

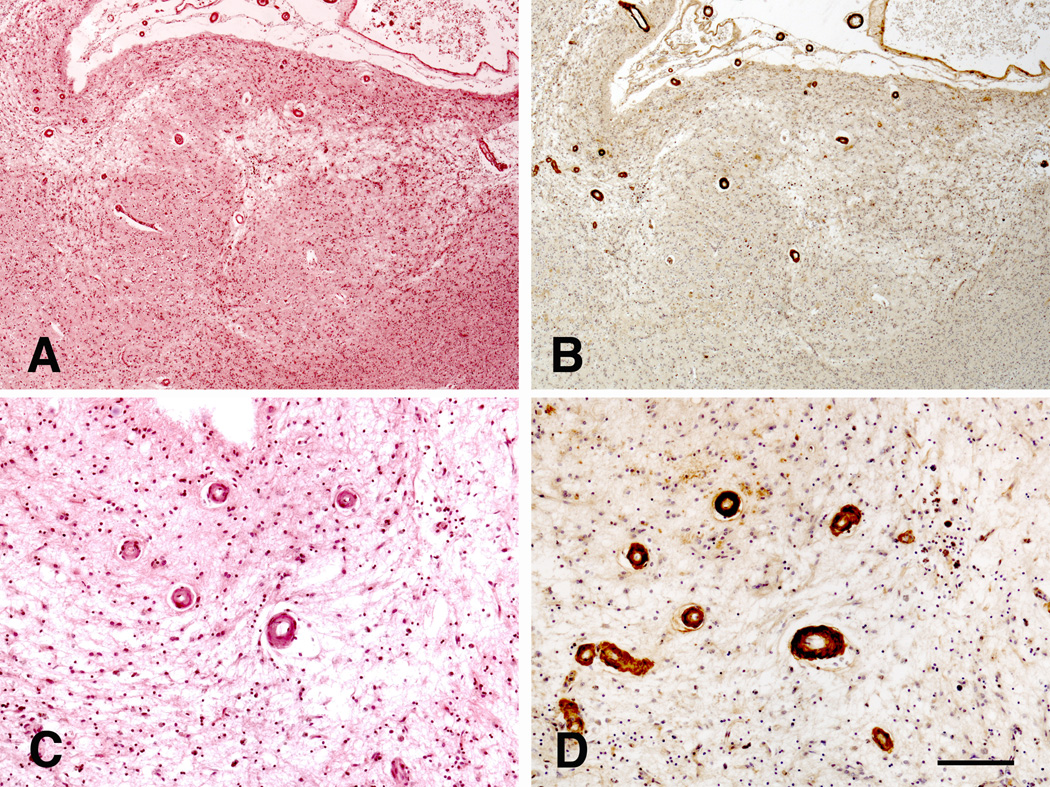

Cortical microinfarcts and other vascular lesions

Thirty-four cases presented with CMI of variable severity. In general, CMI were more numerous in cases with CAA (Fig. 4) than without (21 cases − 61.8% vs. 13 cases − 38.2%), but without reaching statistical significance (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.282; Table 4). Comparably, no significant differences were observed in the case of meningeal (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.394) and intracerebral CAA (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.251). Finally, with the exception of a slight correlation between meningeal CAA and CMI in the frontal cortex (Spearman’s rho = −0.239; p = 0.023), there was no association between the CAA and CMI in any of the other regions. Spearman’s rho ranged from −0.12 (p = 0.266) to 0.134 (p = 0.266) for intracerebral CAA and from −0.12 (p = 0.266) to 0.134 (p = 0.208) for meningeal CAA in the other regions. Comparing different levels of severity (absent or mild versus moderate/severe), no statistical significance was revealed.

Figure 4.

CMI in a case with severe CAA in the parietal cortex. Haematoxylin-eosin (A and C), and immunohistochemistry with anti-amyloid antibody 4G8 (B and D). Scale bar: (A and B): 500 µm; (C and D): 200 µm.

There were only few vascular lesions of other types. Three cases showed microbleeds in the examined regions, and among them only 1 case presented with CAA. Among the 10 cases with macroscopic brain infarcts (9 ischaemic and 1 haemorrhagic), 3 cases displayed CAA. Major intracerebral haemorrhages were found in 4 cases: 2 of them had both meningeal and intracerebral amyloid, one only meningeal amyloid, and the last one no amyloid deposition in vessels’ walls. The low number of these vascular lesions did not permit further statistical analyses.

The mean severity values of CMI and CAA in our series – with exception of occipital cortex, where both lesions were frequent - did not follow the same distribution (Fig. 3E). After the occipital cortex, CAA were more frequent in the temporal cortex, followed by frontal and parietal areas, in contrast to CMI, which were more severe in the frontal cortex and hippocampus.

Discussion

Our retrospective one-year non-selected autopsy study showed that 53.8% of cases had evidence of CAA in intracerebral and/or meningeal vessels. This value was higher in neuropathologically proven AD (in 8 of 10 cases), confirming the results of previous studies [2, 6, 10–14, 42]. While CAA could appear patchy and segmental, non-exhaustive pathological examination can also lead to under-diagnosis [20]. Our results confirmed earlier observations that CAA is largely age-dependent and it showed an increase in severity with age [6–10, 12, 22, 23]. The important observation that only amyloid plaques, but not NFTs, are correlated with CAA, supports previous results reported by Attems et al. [1].

Most authors agree that the regional distribution of CAA exhibits a posterior-to-anterior axis [5, 9, 11, 24, 43]. We confirmed these observations: the occipital cortex was the most affected and hippocampus the less affected regions in our materials [17].

The main result of our study is the absence of a significant correlation between CAA and microvascular brain lesions. Although more frequent in cases with CAA, statistical analyses did not reveal a correlation between vascular Aβ and CMI. This issue has been the subject of many investigations, which have yielded contradictory results (Table 5). Many studies that found a correlation between these two neuropathological lesions were based on populations of AD patients or patients with vascular dementia [16, 28, 30, 34, 44], but the number of studies reporting data from general populations (demented and non-demented) is small [27, 45, 46].

Table 5.

Bibliographic data focusing on the relationship of CAA and CMI

| Author | Population | % of CAA | Cortical microinfarcts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scholz 1938[46] | 104 consecutive autopsies (>70 years old) | 12% | Absence of any type of vascular lesion including CMI close to CAA |

| Grégoretti, 1956 [47] | 100 consecutive psychiatric autopsy cases (40–91 years old) | 27% | CAA more often in cases with CMI in the occipital cortex, but insufficient to cause CMI. ATS more related to CMI |

| Esiri and Wilcock, 1986 [6] | 159 autopsy cases | 82% (AD - 25% severe) 30% (non-AD) |

Multiple CMIs in only 2 cases with CAA |

| Ellis et al., 1996 [12] | 117 AD autopsy | 82.9% (25.6% severe or moderate) | No significant association of CAA with CMI |

| Olichney et al., 1997 [16] | 248 AD autopsy | 20.2 % severe 79.8 % mild/no |

CMI strongly associated with CAA (p = 0.01), in the whole population and in cases with hypertension, but not in normotensive cases (p = 0.07) |

| Haglund et al., 2004 [44] | 22 cases (11 AD, 11 VaD) | More CAA (6/11 severe) in VaD group than in AD | Significant correlation between CAA and CMI in the whole population (p = 0.018), but not in VaD (p = 0.083) |

| Haglund et al., 2006 [30] | 26 VaD cases | 72 % of all VaD cases | Correlation between severe (mainly meningeal) CAA and CMI, however causality not evident |

| Launer et al., 2008 [27] | 439 consecutive autopsy cases (99% with AD – HAAS study) | 62.6 % | No association between vascular lesions and AD-type lesions as NFT, AP, and CAA |

| Soontornniyomkij et al., 2010 [34] | 39 CAA brains (18 severe, 21mild CAA) | n.d. | 77.7% in severe CAA 33.3% in mild CAA |

| De Reuck et al., 2011 [28] | 90 consecutive autopsy cases with clinically suspected AD | 35% severe CAA | Significantly more CMI in CAA cases with sever than with mild AD features, but CMI can not be attributed to CAA alone |

| Okamoto et al., 2012 [45] | 275 consecutive autopsies (14 AD, 17 non-AD) | 11.3 % based on HE-staining in first step | CAA is a significant predictor of CMI in correlations with the severity of CAA |

| Kövari et al., present study | 91 consecutive autopsies | 53.8% | No significant association of CAA with CMI |

CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CMI = cortical microinfarct, ATS = atherosclerosis, AD = Alzheimer’s disease, VaD = vascular dementia, NFT = neurofibrillary tangle, AP = amyloid plaque, n.d. = no data

Our findings confirm the results of Ellis et al. (1996) and Launer et al. (2008). Ellis et al. found a correlation between CAA and haemorrhage and brain infarcts but not with CMIs in his study of 117 consecutive autopsy cases [12]. Launer et al. observed no association in 439 consecutive autopsy cases between vascular lesions and CAA [27]. Interestingly, already in 1938, Scholz did not find any type of vascular lesions, including CMI, in the vicinity of vessels with amyloid deposits [46], and some investigations concluded, as the present study, that in spite of the higher frequency of CMI in cases with CAA, no causal relationship could be firmly established [28, 30, 47].

The absence of a significant difference in CMI number between cases with or without CAA also agrees with the data of Thal et al. [17]. In his series of 41 CAA and 28 control cases, including 16 patients with small infarcts, the number of cases without CAA was higher than that of cases with CAA (9 vs. 7). The observed differences in the distribution of the mean severity values of CAA and CMI (Fig. 3E) presume that CMIs are not direct consequences of amyloid angiopathy and also questions the causality of both pathological lesions.

The importance of CAA in vascular brain changes was revealed mainly after the recognition of pathological complications of Aβ immunotherapy for AD, when CAA, accompanied by CMI and microbleeds occurred more frequently in immunized AD patients than in the control AD group [48]. The origin of vascular amyloid in the brain remains, however, a debated subject. According to one theory, Aβ drains from the brain via pericapillary and periarterial pathways like an interstitial fluid and its deposition in the vessels’ walls is due to perturbed drainage as in the case of arterial occlusion [49–51].

Other observations suggest that vascular amyloid derives from different sources than that seen in amyloid plaques. First, several studies reported that the type of amyloid found in vessels and amyloid plaques represent different subtypes of amyloid (Aβ1–40 vs Aβ1–42) [52–60]. Additionally, as seen in the present series, CAA and amyloid plaques are frequently not associated [12, 19, 61–64]. Many investigators also discussed the possibility that vascular amyloid originates from smooth muscle cells, in situ. CAA is beginning in the medial layer suggesting that it could be a product of smooth muscle cells in the vascular wall [44, 65], resulting from the release of amyloid precursor protein from degenerating smooth muscle cells [49, 66–68]. In fact the Vonsattel et al. grading system for the neuropathological severity of CAA also supports this possibility [10]. The present observation of a dissociation between CAA and amyloid plaques in several cases, and the apparently centripetal “growth” of CAA from meningeal to intracerebral vessels reinforces the notion that vessel-related amyloid is produced locally by smooth muscle cells.

In conclusion, our results show that CAA is more age-related than it is disease-related. The present study does not confirm a correlation between CAA and CMI. Although CMI are more frequent in cases with CAA, the importance of other causes, such as hypertension, arteriosclerosis, microembolisms, or hypotensive episodes, could not be excluded. While further neuropathological investigations in this field are necessary, our results do not support CAA as one of the most important risk factor to developing microvascular lesions and vascular dementia. The role of CAA in developing microvascular lesions also appears to be overestimated. Although the role of CMI in vascular dementia is increasingly recognized [39, 69–71], the identification of its main causative factors remains of major importance for disease prevention.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grant P50 AG05538 (to P.R.H.).

We thank Maria Surini-Demiri for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

C.B., P.R.H., and E.K. designed the study. E.K. did all of the analyses and photography and wrote the paper. F.R.H. performed the statistical analyses. C.B. and P.R.H. provided critical reading of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Attems J, Jellinger KA. Only cerebral capillary amyloid angiopathy correlates with Alzheimer pathology--a pilot study. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;107:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jellinger KA. Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:813–836. doi: 10.1007/s007020200068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revesz T, Ghiso J, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Frangione B, Holton JL. Cerebral amyloid angiopathies: a pathologic, biochemical, and genetic view. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:885–898. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.9.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Frangione B, Rostagno A, Ghiso J. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of sporadic and hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:115–130. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Ghiso J, Frangione B. Sporadic and familial cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:343–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esiri MM, Wilcock GK. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in dementia and old age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:1221–1226. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.11.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jellinger KA, Lauda F, Attems J. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy is not a frequent cause of spontaneous brain hemorrhage. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:923–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomonaga M. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29:151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinters HV, Gilbert JJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: incidence and complications in the aging brain. II. The distribution of amyloid vascular changes. Stroke. 1983;14:924–928. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Ropper AH, Bird ED, Richardson EP., Jr Cerebral amyloid angiopathy without and with cerebral hemorrhages: a comparative histological study. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:637–649. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada M, Tsukagoshi H, Otomo E, Hayakawa M. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the aged. J Neurol. 1987;234:371–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00314080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis RJ, Olichney JM, Thal LJ, Mirra SS, Morris JC, Beekly D, Heyman A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease: the CERAD experience, Part XV. Neurology. 1996;46:1592–1596. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itoh Y, Yamada M, Hayakawa M, Otomo E, Miyatake T. Subpial β/A4 peptide deposits are closely associated with amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Neurosci Lett. 1993;155:144–147. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90693-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joachim CL, Morris JH, Selkoe DJ. Clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease - Autopsy results in 150 cases. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:50–56. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Lancet. 2001;357:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olichney JM, Ellis RJ, Katzman R, Sabbagh MN, Hansen L. Types of cerebrovascular lesions associated with severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;826:493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Yamaguchi H, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Two types of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:282–293. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinters HV. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical review. Stroke. 1987;18:311–324. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olichney JM, Hansen LA, Hofstetter CR, Grundman M, Katzman R, Thal LJ. Cerebral infarction in Alzheimer's disease is associated with severe amyloid angiopathy and hypertension. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:702–708. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540310076019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biffi A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol. 2011;7:1–9. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2011.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard E, Carrano A, Hoozemans JJ, van Horssen J, van Haastert ES, Eurelings LS, de Vries HE, Thal DR, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA, Rozemuller AJ. Characteristics of dyshoric capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:1158–1167. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181fab558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attems J, Lauda F, Jellinger KA. Unexpectedly low prevalence of intracerebral hemorrhages in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: an autopsy study. J Neurol. 2008 Jan;255:70–76. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergeron C, Ranalli PJ, Miceli PN. Amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14:564–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pantelakis S. Un type particuliar d'angiopathie sénile du système nerveux central: l'angiopathie congophile; topographie et fréquence. [A particular type of senile angiopathy of the central nervous system: congophilic angiopathy, topography and frequency] Monatsschr Psychiatr Neurol. 1954;128:219–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Alzheimer's disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandybur TI. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: the vascular pathology and complications. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1986;45:79–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Launer LJ, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Markesbery W, White LR. AD brain pathology: vascular origins? Results from the HAAS autopsy study. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1587–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Leys D, Maurage CA, Pasquier F. The impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy on the occurrence of cerebrovascular lesions in demented patients with Alzheimer features: a neuropathological study. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:913–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Leys D, Pasquier F, Maurage CA. Prevalence of small cerebral bleeds in patients with a neurodegenerative dementia: a neuropathological study. J Neurol Sci. 2011;300:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haglund M, Passant U, Sjobeck M, Ghebremedhin E, Englund E. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cortical microinfarcts as putative substrates of vascular dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:681–687. doi: 10.1002/gps.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimberly WT, Gilson A, Rost NS, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Smith EE, Greenberg SM. Silent ischemic infarcts are associated with hemorrhage burden in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2009;72:1230–1235. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345666.83318.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olichney JM, Hansen LA, Hofstetter CR, Lee JH, Katzman R, Thal LJ. Association between severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cerebrovascular lesions in Alzheimer disease is not a spurious one attributable to apolipoprotein E4. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:869–874. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olichney JM, Hansen LA, Lee JH, Hofstetter CR, Katzman R, Thal LJ. Relationship between severe amyloid angiopathy, apolipoprotein E genotype, and vascular lesions in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;903:138–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soontornniyomkij V, Lynch MD, Mermash S, Pomakian J, Badkoobehi H, Clare R, Vinters HV. Cerebral microinfarcts associated with severe cerebral β-amyloid angiopathy. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:459–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yates PA, Sirisriro R, Villemagne VL, Farquharson S, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Cerebral microhemorrhage and brain β-amyloid in aging and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:48–54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318221ad36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallet PG, Guntern R, Hof PR, Golaz J, Delacourte A, Robakis NK, Bouras C. A comparative study of histological and immunohistochemical methods for neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;83:170–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00308476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–1800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kövari E, Gold G, Herrmann FR, Canuto A, Hof PR, Michel JP, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Cortical microinfarcts and demyelination significantly affect cognition in brain aging. Stroke. 2004;35:410–414. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110791.51378.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brundel M, de Bresser J, van Dillen JJ, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. Cerebral microinfarcts: a systematic review of neuropathological studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:425–436. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okamoto Y, Ihara M, Fujita Y, Ito H, Takahashi R, Tomimoto H. Cortical microinfarcts in Alzheimer's disease and subcortical vascular dementia. Neuroreport. 2009;20:990–996. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832d2e6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishihara T, Takahashi M, Yokota T, Yamashita Y, Gondo T, Uchino F, Iwamoto N. The significance of cerebrovascular amyloid in the etiology of superficial (lobar) cerebral-hemorrhage and its incidence in the elderly population. J Pathol. 1991;165:229–234. doi: 10.1002/path.1711650306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Attems J, Quass M, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its effect on cognitive decline are influenced by Alzheimer disease pathology. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haglund M, Sjobeck M, Englund E. Severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy characterizes an underestimated variant of vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18:132–137. doi: 10.1159/000079192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamoto Y, Yamamoto T, Kalaria RN, Senzaki H, Maki T, Hase Y, Kitamura A, Washida K, Yamada M, Ito H, Tomimoto H, Takahashi R, Ihara M. Cerebral hypoperfusion accelerates cerebral amyloid angiopathy and promotes cortical microinfarcts. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:381–394. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scholz W. Studien zur Pathologie der Hirngefässe II. Die drüsige Entartung der Hirnarterien und Capillaren. Z Ges Neurol Psychiat. 1938;162:694–715. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grégoretti L. Contribution à l'étude des foyers cicatriciels de nécrose parenchymateuse élective de l'écorce cérébrale occipitale et préfrontale [Cicatricial foci of elective parenchymatous necrosis of the occipital and prefrontal cortex] Rev Neurol. 1956;95:207–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Nicoll JA. Consequence of Aβ immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain. 2008;131:3299–3310. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalaria RN. Cerebral vessels in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol Ther. 1996;72:193–214. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weller RO, Massey A, Newman TA, Hutchings M, Kuo YM, Roher AE. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: amyloid β accumulates in putative interstitial fluid drainage pathways in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:725–733. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65616-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weller RO, Yow HY, Preston SD, Mazanti I, Nicoll JA. Cerebrovascular disease is a major factor in the failure of elimination of Aβ from the aging human brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Jr, Younkin LH, Suzuki N, Younkin SG. Amyloid β protein (Aβ) in Alzheimer's disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at Aβ40 or Aβ42(43) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7013–7016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwatsubo T, Mann DM, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Ihara Y. Amyloid β protein (Aβ) deposition: Aβ42(43) precedes Aβ40 in Down syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:294–299. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43) Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwatsubo T, Saido TC, Mann DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Full-length amyloid-β (1–42(43)) and amino-terminally modified and truncated amyloid-β 42(43) deposit in diffuse plaques. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1823–1830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Love S. Contribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mak K, Yang F, Vinters HV, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Polyclonals to β-amyloid(1–42) identify most plaque and vascular deposits in Alzheimer cortex, but not striatum. Brain Res. 1994;667:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mann DM, Iwatsubo T. Diffuse plaques in the cerebellum and corpus striatum in Down's syndrome contain amyloid β protein (Aβ) only in the form of Aβ42(43) Neurodegeneration. 1996;5:115–120. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mann DM, Iwatsubo T, Ihara Y, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL, Bogdanovic N, Lannfelt L, Winblad B, Maat-Schieman ML, Rossor MN. Predominant deposition of amyloid-β 42(43) in plaques in cases of Alzheimer's disease and hereditary cerebral hemorrhage associated with mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1257–1266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saido TC, Iwatsubo T, Mann DM, Shimada H, Ihara Y, Kawashima S. Dominant and differential deposition of distinct β-amyloid peptide species, Aβ N3(pE), in senile plaques. Neuron. 1995;14:457–466. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Armstrong RA, Myers D, Smith CU. The ratio of diffuse to mature β/A4 deposits in Alzheimer's disease varies in cases with and without pronounced congophilic angiopathy. Dementia. 1993;4:251–255. doi: 10.1159/000107330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lippa CF, Hamos JE, Smith TW, Pulaski-Salo D, Drachman DA. Vascular amyloid deposition in Alzheimer's disease. Neither necessary nor sufficient for the local formation of plaques or tangles. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:1088–1092. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540100073019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rozemuller AJ, Roos RA, Bots GT, Kamphorst W, Eikelenboom P, Van Nostrand WE. Distribution of β/A4 protein and amyloid precursor protein in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1993 May;142:1449–1457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tian J, Shi J, Bailey K, Mann DM. Negative association between amyloid plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2003;352:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wisniewski HM, Wegiel J. β-amyloid formation by myocytes of leptomeningeal vessels. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00296738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davis-Salinas J, Saporito-Irwin SM, Cotman CW, Van Nostrand WE. Amyloid β-protein induces its own production in cultured degenerating cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. J Neurochem. 1995;65:931–934. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65020931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frackowiak J, Mazur-Kolecka B, Wisniewski HM, Potempska A, Carroll RT, Emmerling MR, Kim KS. Secretion and accumulation of Alzheimer's β-protein by cultured vascular smooth muscle cells from old and young dogs. Brain Res. 1995;676:225–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01465-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kawai M, Kalaria RN, Cras P, Siedlak SL, Velasco ME, Shelton ER, Chan HW, Greenberg BD, Perry G. Degeneration of vascular muscle cells in cerebral amyloid angiopathy of Alzheimer disease. Brain Res. 1993;623:142–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90021-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kalaria RN, Kenny RA, Ballard CG, Perry R, Ince P, Polvikoski T. Towards defining the neuropathological substrates of vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2004;226:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kövari E, Gold G, Herrmann FR, Canuto A, Hof PR, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Cortical microinfarcts and demyelination affect cognition in cases at high risk for dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:927–931. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257094.10655.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, Nelson J, Davis DG, Ross GW, Masaki K, Launer L, Markesbery WR. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]