Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine whether Strongyloides stercoralis FKTF-1, a transcription factor of the FOXO/FKH family and the likely output of insulin/IGF signal transduction in that parasite, has the same or similar developmental regulatory capabilities as DAF-16, its structural ortholog in Caenorhabditis elegans. To this end, both splice variants of the fktf-1 message were expressed under the control of the daf-16α promoter in C. elegans carrying loss of function mutations in both daf-2 (the insulin/IGF receptor kinase) and daf-16. Under well-fed culture conditions the majority (91%) of untransformed daf-2; daf-16 double mutants developed via the continuous reproductive cycle, whereas under the same conditions 100% of daf-2 single mutants formed dauers. Transgenic daf-2; daf-16 individuals expressing fktf-1b showed a reversal of the double mutant phenotype with 75% of the population forming dauers under well-fed conditions. This phenotype was even more pronounced than that of daf-2; daf-16 mutants transformed with a homologous rescuing construct, daf-16α::daf-16a (56% dauers under well fed conditions), indicating that S. stercoralis fktf-1b can almost fully rescue loss-of-function mutants in C. elegans daf-16. By contrast, daf-2; daf-16 mutants expressing S. stercoralis fktf-1a, encoding the second splice variant of FKTF-1, showed a predominantly continuous pattern of development identical to that of the parental double mutant stock. This indicates that, unlike FKTF-1b, the S. stercoralis transcription factor FKTF-1a cannot trigger the shift to dauer-specific gene expression in C. elegans.

Keywords: Strongyloides stercoralis, Caenorhabditis elegans, Dauer larva, Infective larva, Fork head transcription factor, Transgenesis

1. Introduction

Morphological, developmental and behavioral similarities between the infective third-stage larvae of parasitic nematodes (L3i) and dauer larvae of Caenorhabditis elegans have led to the hypothesis that the development of L3i and of C. elegans dauers may be regulated by common molecular and cellular mechanisms (Hotez et al., 1993; Blaxter and Bird, 1997; Blaxter, 1998; Burglin et al., 1998). This hypothesis has been bolstered by the discovery that dauer switching in C. elegans and the switch between homogonic and heterogonic developmental alternatives in the parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis are controlled by the homologous amphidial neurons (Bargmann and Horvitz, 1991; Ashton et al., 1998; Nolan et al., 2004). Our laboratory is investigating possible parallels between molecular mechanisms regulating dauer development in C. elegans and the development of L3i in S. stercoralis. In C. elegans, dauer arrest is controlled by three interacting cellular signal transduction pathways: a G protein coupled odorant receptor pathway that processes signals from a constitutively secreted dauer pheromone (Zwaal et al., 1997) and TGF-β- (Georgi et al., 1990; Bargmann and Horvitz, 1991; Estevez et al., 1993; Ren et al., 1996; Nolan et al., 2002) and insulin-like (Morris et al., 1996; Kimura et al., 1997; Ogg et al., 1997; Ogg and Ruvkun, 1998; Paradis and Ruvkun, 1998; Paradis et al., 1999; Li et al., 2003) pathways that transduce signals from sensory neurons in the amphids to multiple tissues that are remodeled during dauer development. We have discovered that orthologs of genes in all three of these signal transduction pathways are conserved in S. stercoralis (Massey et al., 2001, 2003, 2005) and we are investigating the possible role of insulin-like signaling in regulating L3i development in this parasite.

Under environmental conditions favoring continuous, reproductive development, output from the insulin-like pathway in C. elegans negatively regulates DAF-16, a forkhead, winged helix-class transcription factor, causing it to remain localized in the cytoplasm. Under dauer inducing conditions, insulin-like signaling ceases and DAF-16 assumes a nuclear localization where it shifts the pattern of gene expression to one favoring dauer arrest and lifespan extension. Loss-of-function mutations in daf-16 result in a dauer deficient (daf-d) phenotype and suppress the dauer constitutive and lifespan extension phenotypes associated with mutations in all known upstream kinases in the insulin pathway, suggesting that negative regulation of daf-16 is the major output of this pathway (Lin et al., 1997; Ogg et al., 1997).

Recently, we discovered fktf-1, an S. stercoralis ortholog of daf-16 in C. elegans (Massey et al., 2003). The structures of fktf-1 and daf-16, of their alternately spliced transcripts and of their predicted peptide products are similar. The predicted peptide sequences of FKTF-1A and DAF-16A1, for example, show the highest levels of homology (79.5% identity) in their DNA-binding or ‘forkhead’ domains. Lower levels of homology are predicted for the C-terminal (31.4% identity) and N-terminal (51.4% identity) domains of these proteins. The latter value excludes the serine rich region predicted at the N terminus of FKTF-1A (Massey et al., 2003). Like its C. elegans ortholog, fktf-1 is expressed at similar levels throughout development (Ogg et al., 1997; Massey et al., 2003). The splice variants of the daf-16 transcript are expressed in various tissues and anatomical sites that undergo remodeling during dauer development, each under the control of its own promoter, (Lee et al., 2001). The anatomical expression patterns of fktf-1 are unknown at this time.

At present, the lack of functional genomic methods prevents direct assessment of fktf-1 function in S. stercoralis. An alternative approach to obtaining information about the functional capabilities of fktf-1 might be to characterize its ability to complement daf-16 loss of function mutations in C. elegans by transgenesis. This approach has been used to assess functional conservation of promoter elements (Britton et al., 1999; Gomez-Escobar et al., 2002) and coding sequences (Britton and Murray, 2002) from other parasite genes. In the present paper, we have taken a similar approach with fktf-1 from S. stercoralis. We showed that when expressed as a transgene, one of its alternately spliced transcripts could restore dauer-forming capability to C. elegans carrying a loss-of-function mutation in daf-16, thus demonstrating possible functional homology of the two genes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Genetic stocks of C. elegans

Starting cultures of the N2 (wild-type) strain of C. elegans, the single mutant daf-2 (e1370) and the double mutant daf-2 (e1370); daf-16 (mg54) strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota). Worms from all genetic stocks as well as transgenic lines were maintained on NGM agar plates with Escherichia coli OP50 lawns using standard methods (Lewis and Fleming, 1995).

2.2. Transformation constructs

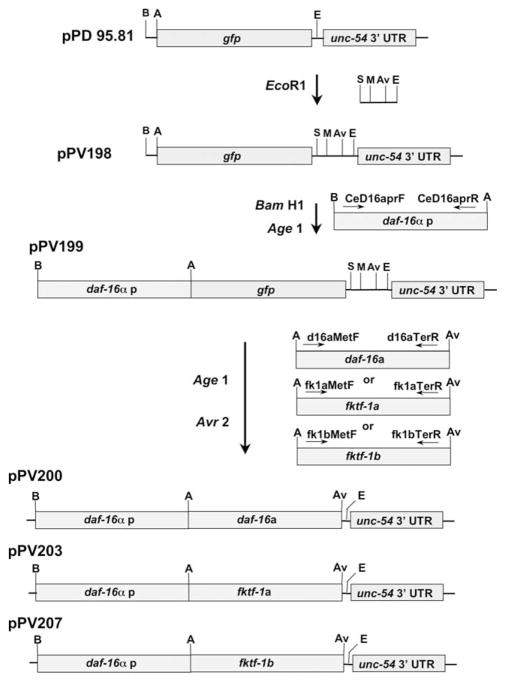

The vector pPV198 (Fig. 1) was made from the C. elegans vector pPD95.81 (gift from Andrew Fire). pPD95.81 was cut at the Eco R1 site between the gfp coding sequence and the unc- 54 3′ end cassette and the oligonucleotide sequence (5′-AAT TAC GCG TCC TAG GCC TG-3′) adding restriction sites for Stu1, Mlu1, Avr2 upstream of Eco R1. The C. elegans daf-16α promoter (Ogg et al., 1997) was amplified from genomic DNA with the primers CeD16aprF and CeD16aprR tagged with restriction sites for BamH1 and Age1, respectively. This was cloned into pPCRScript Amp SK+ (Stratagene), and the BamH1, Age1 fragment from this construct was inserted into pPV198 to create pPV199 (Fig. 1) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNAs encoding daf-16a, fktf-1a and fktf-1b were amplified by reverse trancsriptase (RT)-PCR using the SuperScript First Strand Synthesis System® (Invitrogen) and the following primers in the PCR step: D16aMetF and D16TerR (daf-16a), FK1aMetF and FK1TerR (fktf-1a), and FK1bMetF and FK1TerR (fktf-1b). Sequences of these primers are given in Table 1. All forward and reverse primers used to amplify daf-16 or fktf-1 coding sequences contained an Age1 or Avr2 restriction site, respectively, for cloning. Amplified coding sequences were cloned into pPCRScript Amp SK+(Stratagene). The cDNAs were cut from the pPCR-Script clones with Age1 and Avr2 and ligated to pPV199 from which the gfp sequence had been removed with the same restriction endonucleases to make pPV200, pPV203 and pPV207 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cloning strategy for reporter and rescuing constructs. Starting material is the Caenorhabditis elegans vector pPD 95.81, kindly provided by A. Fire. Preliminary steps involve inserting a supplemental cloning cassette with restriction sites for Stu1 (S), Mlu1 (M) and Avr2 (Av) at the EcoR1 site (E) upstream of the unc-54 3′ untranslated region (UTR) to yield plasmid pPV198 and the daf-16α promoter at the Bam H1 (B) and Age1 (A) sites upstream of the gfp coding sequence to yield the reporter construct, plasmid pPV199. Rescuing constructs containing coding sequences for daf-16a (pPV200), fktf-1a (pPV203) or fktf-1b (pPV207) were made by first removing the gfp coding sequence from pPV199 by digestion with Age1 and Avr2 and ligating the appropriate cDNAs, generated with Age1- and Avr2-compatible ends by reverse transcriptase-PCR, at these same restriction sites.

Table 1.

PCR primers used to amplify promoters and coding sequences for synthesis of transformation constructs (see Fig. 1) used for Caenorhabditis elegans complementation studies

| Element | Primer designation | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| daf-16a promoter | CeD16aprF | 5′-GATGGATCCTCTGATTGGCTTCTCGTGGTG-3′a |

| CeD16aprR | 5′-TCTACCGGTATTTCAGCCAAAGACGACGATG-3′b | |

| daf-16a coding sequence | d16aMetF | 5′-AATACCGGTAGACGTTATGATGGAGATGCTGG-3′b |

| d16aTerR | 5′-CGTTTTTGGTACCTAGGTCAGTGCTAATGATTTTACTATCTGG-3′c | |

| fktf-1a coding sequence | fk1aMetF | 5′-AATACCGGTAAGAGTAAAAATGAGTGGACATC-3′b |

| fk1aTerR | 5′-AAACCTAGGTTTGTTACAACTTTTAGGAATC-3′c | |

| fktf-1b coding sequence | fk1bMetF | 5′-ATAACCGGTAAAAATGAATACATCCATTGTATCGG-3′b |

| fk1bTerR | 5′-AAACCTAGGTTTGTTACAACTTTTAGGAATC-3′c |

BamH1 restriction site underscored.

Age1 restriction site underscored.

Avr2 restriction site underscored.

2.3. DNA transformation of C. elegans and selection of transgenic lines

Caenorhabditis elegans of the daf-2; daf-16 double mutant background were transformed by microinjection of the test constructs at a final concentration of 20 ng/μl into the distal gonad arms of L4 or young hermaphrodites. Plasmid pRF4 (a gift from M. Sundaram, University of Pennsylvania) containing the rol-6 marker was co-injected with each transgene construct at a final concentration of 80 ng/μl. This transgene encodes a cuticular collagen with a dominant mutation resulting in the abnormal ‘right roller’ motility phenotype, allowing easy identification and manual selection of transformants (Kramer et al., 1990; Mello et al., 1991). Microinjected worms were reared in isolation, and transformants were selected from among their F1 progeny and re-plated. Progeny of individual microinjected worms that transmitted transgenes to the F2 generation and beyond were maintained as independent transgenic lines.

Cell-specific expression was indicated by gfp expression and viewed under a fluorescent microscope.

2.4. Assay for dauer switching in C. elegans mutants and transgenic lines

In order to assess effects of various transgenes on dauer switching in C. elegans, we used an assay for dauer switching based on that outlined previously (Nolan et al., 2002). This assay involves evaluating development of synchronized cohorts of worms under uniform non-dauer inducing conditions. Mutant strains used as controls in these experiments were stably transformed with the rol-6 plasmid, pRF4. Briefly, 10–20 egg-laying transformant (roller) hermaphrodites were placed on 60 mm NGM agar plates with standard E. coli OP50 lawns formed by drying 40 μl of an overnight LB broth culture with cell density adjusted to 0.25% w/v. The worms were allowed to oviposit for 3–8 h and then removed from their respective plates. The aim was to accumulate a semi-synchronous population of 50–100 eggs from each line on an individual assay plate. The plates were then incubated at 25 °C for 65–70 h. At the end of this incubation, individual transformants were picked either to a separate plate or a clear area of their own plate and scored as non-dauer individuals (L4s or adults) or dauer larvae. These assessments were made based on radial constriction of the body and on filariform pharyngeal morphology and lack of pharyngeal pumping (Riddle and Albert, 1997). Mean proportions of dauer and non-dauer development were calculated from at least two replicate assays, conducted on different days, of at least two independently derived lines for each transgene construct. Proportions of dauer and non-dauer development in transgenic lines were compared to those in the daf-2; daf-16 parental stock by χ2 analysis, and P less than or equal to 0.05 was set as the criterion for significance.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of test constructs in C. elegans mutants

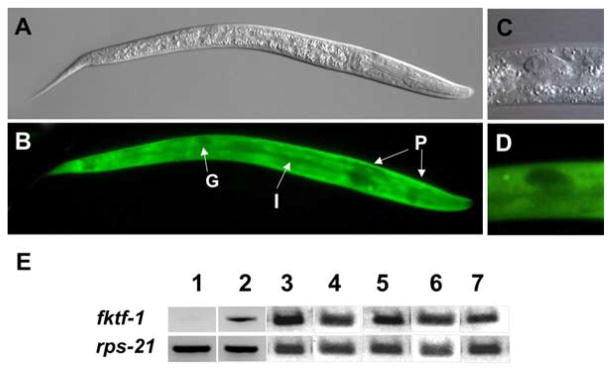

The daf-16α promoter::gfp fusion construct (pPV199, Fig. 1) was expressed in all life stages of C. elegans transformants. Bright fluorescence was seen in cells of the body wall, muscles, intestine and neurons but not in the pharynx or gonad (Fig. 2A–D). Messenger RNA encoding FKTF-1 was amplified by RT-PCR using fktf-1-specific primers in all lines created by transforming daf-2; daf-16 double mutants with our daf-16α::fktf-1a (pPV203) or daf-16α::fktf-1b (pPV207) rescuing constructs (Fig. 2E). An RTPCR signal, presumably from the mutant daf-16(mg54) message prevented this type of confirmatory analysis in our control lines transformed with the homologous rescuing construct daf-16α::daf-16a.

Fig. 2.

Expression of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans strains. (A,B), DIC and fluorescence images, respectively, of N2 (wild type) L1 expressing daf- 16α::gfp. Note generalized expression in body wall and intestine (I) and lack of expression in pharynx (P) and gonad (G). (C,D), DIC and fluorescence images, respectively detailing characteristic lack of daf-16α::gfp expression in gonad. (E), results of reverse transcriptase-PCR to detect fktf-1-specific mRNA in daf- 2; daf-16 trangenic lines. The constitutively expressed mRNA encoding the ribosomal protein small subunit RPS-21 was used as a loading control. Templates in lanes as follows: (1), untransformed parental daf-2; daf-16 double mutant stock; (2–5) daf-16α::fktf-1b transformant lines 031003-3, 020403-16, 021805-10 and 170304-10, respectively; 6–7, daf-16α::fktf-1a transformant lines 020105-17 and 2251103-6, respectively.

3.2. Results of cross-species complementation experiments

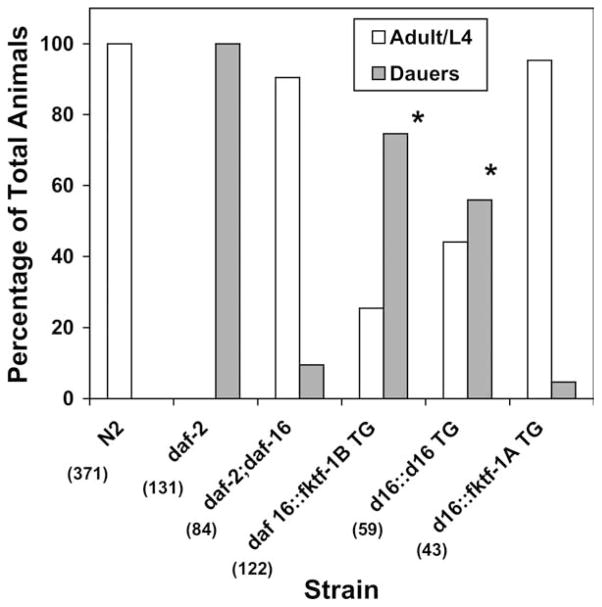

Percentages of dauer and non-dauer development in wild type, mutant and transgenic C. elegans are shown in Fig. 3. Patterns of development in untransformed N2 (wild-type) worms, daf-2 mutants and daf-2; daf-16 double mutants transformed only with the rol-6 encoding plasmid pRF4 were consistent with those reported previously for worms of these strains developing under well-fed conditions (Kimura et al., 1997; Lin et al., 1997; Ogg et al., 1997). Note especially the uniform daf-c phenotype of daf-2 and the suppression of this phenotype by a second mutation in daf-16. Interestingly, the heterologous transgene construct daf-16α::fktf-1b resulted in partial restoration of constitutive dauer development in C. elegans daf-2; daf-16 double mutants, indicating that FKTF-1b can partially replace DAF-16 function. χ2 comparison of this result with proportion of dauer and non-dauer development in the parental daf-2; daf-16 stock was highly significant (P<0.005). On the other hand, when worms from this strain were transformed with the daf-16α::fktf-1a construct they showed no appreciable change in their patterns of dauer switching compared with the parental daf-2; daf-16 strain (P>0.9). Finally, transformation of the daf-2; daf-16 double mutant with the homologous daf-16α::daf-16a construct also resulted in a statistically significant departure from the developmental pattern in the daf-2; daf-16 parental stock (P<0.005), indicating partial complementation of the daf-16 mutation.

Fig. 3.

Results of dauer developmental assay on mutant and transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans stocks. Data are pooled from three replicate experiments on at least two independently derived lines for each transgene. Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of worms scored in all experiments. *Denotes statistically significant (P<0.005) difference from proportions of dauer and non-dauer development in parental daf-2; daf-16 stock.

4. Discussion

The daf-2; daf-16 double mutant used in this study provided a convenient subject in which to study fktf-1 function since restoration of daf-16-like activity in this genetic background could be easily quantified by assaying the frequency of dauer development in well-fed cultures. Another important methodological point is that the daf-16α promoter we derived and used in all transgene constructs in this study drove GFP expression primarily in body wall and intestine, a subset of tissues known to be remodeled during dauer development in C. elegans (Ogg et al., 1997). This, along with the conspicuous lack of reporter expression observed in the gonad and pharynx of L1 transformants, is consistent with anatomical patterns of daf-16α promoter activation reported by others for C. elegans L1 (Ogg et al., 1997) and indicates that the promoter element we derived functioned normally and drove expression of the fktf-1 transcripts in the appropriate cell and tissue types. The finding that fktf-1b complements a loss-of-function mutation in daf-16 indicates that the product of this gene is capable of effecting the switch to dauer-specific gene expression in C. elegans. This result is not surprising given the highly conserved domain structure, putative Akt/PKB phosphorylation sites and high degree of sequence identity in the DNA binding domains of FKTF-1, DAF-16 and their orthologs in other systems (Massey et al., 2003). Indeed, Lee et al. (2001) have shown that the insulin-regulated forkhead transcription factor FKHRL-1 from humans will partially complement mutations in daf-16. The fact that the fktf-1b gene product can be appropriately regulated and can shift gene expression in C. elegans to a pattern favoring the developmental and biochemical modifications involved in dauer arrest in the L3 supports the hypothesis that, under the control of insulin-like signaling, it regulates the strikingly similar process of heterogonic-to-homogonic life cycle switching in S. stercoralis. This, in turn, supports the hypothesis that parasitic nematodes have adapted the neural and cell signaling mechanisms governing dauer development in C. elegans to regulating the development of their morphologically and physiologically similar L3i (Hotez et al., 1993; Ashton et al., 1998; Blaxter, 1998; Burglin et al., 1998; Tissenbaum et al., 2000).

The daf-2; daf-16 double mutant stock used in this study contains the mg54 allele in daf-16. This mutation produces an amber stop mutation in the DNA binding domain of daf-16a, but it is not predicted to affect daf-16b splice variant. Our finding that daf-16a mutations can be complemented by fktf-1b is consistent with the findings of Lee et al. (2001) that the respective functions of the ‘a’ and ‘b’ splice forms of daf-16 are determined not by differences in their intrinsic structures but rather by the tissue specificities of their individual promoters. daf-16a and daf-16b are functionally equivalent in pharyngeal remodeling when expressed under the control of the pharynx-specific daf-16β promoter. Likewise the two splice forms are functionally equivalent when expressed under the control of the daf-16α promoter in gut and body wall tissues (Lee et al., 2001). On the other hand, the failure of fktf-1a to complement the daf-16 (mg54) mutation may stem from a marked structural peculiarity predicted for the S. stercoralis protein. Conceptual translations predict a long serine-rich region at the N terminus of FKTF-1a. This motif is predicted to be absent in FKTF-1b and DAF-16b and much reduced in DAF-16a (Massey et al., 2003) and may prevent FKTF-1a from carrying out its developmental regulatory function in C. elegans. It should be possible to test this hypothesis in the C. elegans surrogate system by observing developmental phenotypes resulting from expression of chimeric gene constructs in which the sequence encoding the serine-rich domain is deleted from fktf-1a or appended to the coding sequence of daf-16a or fktf-1b.

Insulin-like signal transduction regulates lifespan as well as larval development in C. elegans (Kenyon et al., 1993; Lin et al., 1997; Apfeld and Kenyon, 1999; Kenyon, 2001; Murphy et al., 2003). In addition to dauer constitutive development, loss-of-function mutations in DAF-2 and other intermediates in the cellular kinase signaling cascade also result in lifespan extension. Similar to their suppression of upstream dauer constitutive phenotypes, mutations in daf-16 also suppress the lifespan extension resulting from mutations in upstream signaling intermediates. Grant et al. (in press) have noted that extreme longevity is common to many parasitic nematodes and that the life cycles of Rhabditoid parasites such as Parastrongyloides trichosuri and Strongyloides spp. feature great disparities in longevity, with parasitic adults living for many weeks and their more ephemeral free-living counterparts living for a few days only. Our laboratory is currently using the C. elegans surrogate system to investigate the capability of fktf-1 and other putative insulin signaling elements from S. stercoralis to regulate lifespan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI-50688 to J.B. Lok, AI-22662 to G.A. Schad and RR02512 to M. Haskins) and The Ellison Medical Foundation (Grant No. ID-IA-0037-02 to J.B. Lok). We thank Qiukan Chen, Mario Brenes, Linda Capewell, Andrea Freeman and Laura Leighton for technical assistance and, for providing C. elegans strains, the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, University of Minnesota, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources.

References

- Apfeld J, Kenyon C. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402:804–809. doi: 10.1038/45544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton FT, Bhopale VM, Holt D, Smith G, Schad GA. Developmental switching in the parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis is controlled by the ASF and ASI amphidial neurons. J Parasitol. 1998;84:691–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Horvitz HR. Control of larval development by chemosensory neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1991;251:1243–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.2006412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. Caenorhabditis elegans is a nematode. Science. 1998;282:2041–2046. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M, Bird D. Parasitic nematodes. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 1997. pp. 851–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton C, Murray L. A cathepsin L protease essential for Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis is functionally conserved in parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;122:21–33. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton C, Redmond DL, Knox DP, McKerrow JH, Barry JD. Identification of promoter elements of parasite nematode genes in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;103:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burglin TR, Lobos E, Blaxter ML. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for parasitic nematodes. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:395–411. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez M, Attisano L, Wrana JL, Albert PS, Massague J, Riddle DL. The daf-4 gene encodes a bone morphogenetic protein receptor controlling C. elegans dauer larva development. Nature. 1993;365:644–649. doi: 10.1038/365644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgi LL, Albert PS, Riddle DL. daf-1, a C. elegans gene controlling dauer larva development, encodes a novel receptor protein kinase. Cell. 1990;61:635–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90475-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Escobar N, Gregory WF, Britton C, Murray L, Corton C, Hall N, Daub J, Blaxter ML, Maizels RM. Abundant larval transcript-1 and -2 genes from Brugia malayi: diversity of genomic environments but conservation of 5′ promoter sequences functional in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;125:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant WN, Stasiuk S, Newton-Howes J, Ralston M, Bisset SA, Heath DD, Shoemaker CB. Parastrongyloides trichosuri, a nematode parasite of mammals that is uniquely suited to genetic analysis. Int J Parasitol. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.11.009. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P, Hawdon JM, Schad GA. Hookworm larval infectivity, arrest and amphiparatenesis: the Caenorhabditis elegans daf-c paradigm. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:23–26. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90159-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. Regulation of longevity by insulin/igf-1 signaling, sensory neurons and the germline in the nematode C. Elegans. Sci World J. 2001;1:132. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2001.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277:942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM, French RP, Park EC, Johnson JJ. The Caenorhabditis elegans rol-6 gene, which interacts with the sqt-1 collagen gene to determine organismal morphology, encodes a collagen. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2081–2089. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RY, Hench J, Ruvkun G. Regulation of C. elegans DAF-16 and its human ortholog FKHRL1 by the daf-2 insulin-like signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1950–1957. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Fleming JT. Basic culture methods. In: Epstein HF, Shakes DC, editors. Methods in Cell Biology. Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Vol. 48. Academic Press; New York: 1995. pp. 4–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Kennedy SG, Ruvkun G. daf-28 encodes a C. elegans insulin superfamily member that is regulated by environmental cues and acts in the DAF-2 signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2003;17:844–858. doi: 10.1101/gad.1066503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. daf-16: an HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278:1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey HC, Jr, Ball CC, Lok JB. PCR amplification of putative gpa-2 and gpa-3 orthologs from the (A+T)-rich genome of Strongyloides stercoralis. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey HC, Jr, Nishi M, Chaudhary K, Pakpour N, Lok JB. Structure and developmental expression of Strongyloides stercoralis fktf-1, a proposed ortholog of daf-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1537–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00205-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey HC, Castelletto M, Bhopale VM, Schad G, Lok JB. Ssttgh- 1 from Strongyloides stercoralis encodes a proposed ortholog of daf-7 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;142:116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb DT, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. Eur Mol Biol Org J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JZ, Tissenbaum HA, Ruvkun G. A phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase family member regulating longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1996;382:536–539. doi: 10.1038/382536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan KM, Sarafi-Reinach TR, Horne JG, Saffer AM, Sengupta P. The DAF-7 TGF-beta signaling pathway regulates chemosensory receptor gene expression in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3061–3073. doi: 10.1101/gad.1027702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan TJ, Brenes M, Ashton FT, Zhu X, Forbes WM, Boston R, Schad GA. The amphidial neuron pair ALD controls the temperature-sensitive choice of alternative developmental pathways in the parasitic nematode, Strongyloides stercoralis. Parasitology. 2004;129:753–759. doi: 10.1017/s0031182004006092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Ruvkun G. The C. elegans PTEN homolog, DAF-18, acts in the insulin receptor-like metabolic signaling pathway. Mol Cell. 1998;2:887–893. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, Patterson GI, Lee L, Tissenbaum HA, Ruvkun G. The fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature. 1997;389:994–999. doi: 10.1038/40194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis S, Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans Akt/PKB transduces insulin receptor-like signals from AGE-1 PI3 kinase to the DAF-16 transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2488–2498. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis S, Ailion M, Toker A, Thomas JH, Ruvkun G. A PDK1 homolog is necessary and sufficient to transduce AGE-1 PI3 kinase signals that regulate diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1438–1452. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren P, Lim CS, Johnsen R, Albert PS, Pilgrim D, Riddle DL. Control of C. elegans larval development by neuronal expression of a TGF-beta homolog. Science. 1996;274:1389–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle DL, Albert PS. Genetic and environmental regulation of dauer larva development. In: Riddle DL, editor. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Plainview, NY: 1997. pp. 739–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum HA, Hawdon J, Perregaux M, Hotez P, Guarente L, Ruvkun G. A common muscarinic pathway for diapause recovery in the distantly related nematode species Caenorhabditis elegans and Ancylostoma caninum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:460–465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaal RR, Mendel JE, Sternberg PW, Plasterk RH. Two neuronal G proteins are involved in chemosensation of the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer-inducing pheromone. Genetics. 1997;145:715–727. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]