Abstract

Action observation (AO), observing another individual perform an action, has been implicated in several higher cognitive processes including forming basic motor memories. Previous work has shown that physical practice (PP) results in cortical motor representational changes, referred to as use-dependent plasticity (UDP), and that AO combined with PP potentiates UDP in both healthy adults and stroke patients. In humans, AO results in activation of the ventral premotor cortex (PMv), however, whether PMv activation has a functional contribution to UDP is not known. Here, we studied the effects disruption of PMv has on UDP when subjects performed PP combined with AO (PP+AO). Subjects participated in 2 randomized-crossover sessions measuring the amount of UDP resulting from PP+AO while receiving disruptive (1Hz) transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over the fMRI activated PMv or over orbito-frontal cortex (FC, Sham). We found that unlike the sham session, disruptive TMS over PMv reduced the beneficial contribution of AO to UDP. To ensure that disruption of PMv was specifically interfering with the contribution of AO and not PP, subjects completed two more control sessions where they performed only PP while receiving disruptive TMS over PMv or FC. We found that the magnitude of UDP for both control sessions was similar to PP+AO with TMS over PMv. These findings suggest that the fMRI activation found in PMv during action observation studies is functionally relevant to task performance, at least for the beneficial effects that AO exerts over motor training.

Keywords: Motor control, Neural Plasticity, Neurophysiology, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Introduction

Action observation (AO), defined as observing another individual perform a task, has recently been implicated in a number of higher cognitive processes like understanding the actions and intentions of others (Iacoboni et al. 2005), imitation learning (Iacoboni et al. 1999), and motor learning (Mattar & Gribble, 2005), as well as disorders like autism (Cattaneo et al., 2009). In the motor domain, the mere observation of skill training can lead to performance improvements (Brass et al., 2001; Heyes & Foster, 2002; Vinter & Perruchet, 2002; Mattar & Gribble, 2005).

Human studies have shown that simple repetitive movements can elicit cortical motor representational changes referred to as use-dependent plasticity (UDP) (Classen et al., 1998; Bütefisch et al., 2004; Stefan et al., 2005, 2008; Celnik et al., 2006, 2008). Given that this form of plasticity encodes the specific kinematic aspects of the recently practiced movement, UDP has been interpreted as being indicative of a formation of a motor memory and possibly one of the initial steps in skill development (Classen et al., 1998). Interestingly, observing another individual perform the same repetitive training (i.e. action observation) elicits similar corticomotor representational changes or memory formation (Stephan et al., 2005). Furthermore, when this action observation (AO) is combined with physical practice, the training effects are quantitatively enhanced beyond what either intervention alone can do in young healthy adults (Stefan et al., 2008), older healthy adults, (Celnik et al., 2006) and stroke patients (Celnik et al., 2008).

Human imaging studies have indirectly shown an increased activation in the rostral part of the inferior parietal lobe (IPL) and the ventral premotor cortex (PMv) in association with AO (Iacoboni et al. 1999; Buccino et al. 2001; Buccino et al. 2004a; Buccino et al. 2004b; Iacoboni et al. 2005). Physiological studies in humans have also demonstrated that AO results in increased excitability of the cortical representation in the primary motor cortex (M1) of the muscles participating in the observed training (Fadiga et al., 1995; Hari et al., 1998; Nishitani et al., 2000; Edwards et al., 2003). Furthermore, recent studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) have shown that AO changes the excitability of connections between PMv and M1 (Koch et al., 2010; Lago et al., 2010). These investigations have proposed that during AO, connections from PMv map the observed movement onto the same neuronal substrate that is involved for generating the movements (Cattaneo et al. 2009) and this drives the performance improvements associated with action observation. However, whether the activation observed in the human PMv area is crucial to the behavioral or physiological effects of AO or is a mere epiphenomenon has not been determined. In this study, we investigated the functional relevance of PMv activation resulting from AO using fMRI-guided transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). We hypothesized that disruptive TMS over PMv while healthy individuals perform physical practice combined with action observation would disrupt the additive effect action observation has on use-dependent plasticity. Thus, we predicted that disruptive PMv stimulation would result in less UDP changes as a consequence of PP+AO, and would have a similar magnitude as performing physical practice alone.

Methods

Ten healthy, right-handed subjects (4 men, 6 women, ranging from ages 19-27) with no history of neurological disorders participated in this study. All subjects gave informed consent approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and in accordance to the declaration of Helsinki.

Recording Procedures

Participants sat comfortably with the right forearm supported in a semipronated position in a molded arm cast that allowed the thumb to move unrestrained. Electromyographic (EMG) activity was recorded with disposable surface electrodes placed over the right extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) and right flexor pollicis brevis (EPB) muscles. Signals were sampled at 2 kHz, visually displayed on-line, and analyzed off-line using MATLAB (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Kinematic measurements were made with a two-dimensional accelerometer (Kistler Instruments, Amherst, NY) mounted on the distal portion of the first thumb phalanx. Movement directions were calculated from the first peak acceleration vector composed of two components: acceleration in the vertical (extension-flexion) axis and in the horizontal (adduction-abduction) axis (Classen et al., 1998).

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

In all conditions, we applied transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) using a fan-cooled figure-of-eight coil connected to a super rapid magnetic stimulator (Magstim 2002). Using a frameless neuronavigation system (BrainSight, Rogue Research, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) we first coregistered the subjects' heads to their magnetic resonance images. We then identified and marked as “hot spot” the area of the primary motor cortex (M1) that elicited isolated and directionally consistent thumb movements. In this location, we determined the resting motor threshold (rMT) for the FPB and EPB as the minimum TMS intensity that evoked a motor evoked potential (MEP) of 50 mV in at least 5 out of 10 trials in the resting target muscle (Rossini et al., 1994). Muscle relaxation was monitored by visual feedback of the EMG recording.

Experimental Procedure

Each subject participated in 2 crossover counterbalance-ordered sessions designed to assess the amount of UDP changes as previously described (Classen et al., 1998; Stefan et al., 2005; Stefan et al., 2008; Celnik et al., 2008). Briefly, at the beginning of each session (separated by at least 7 days), we determined the direction of 65 TMS-evoked thumb movements elicited at a frequency of 0.1Hz over the hot spot (Fig. 1). The mean direction of these 65 movements constituted the baseline TMS-evoked thumb movement direction. After this, subjects underwent one of 2 interventions:

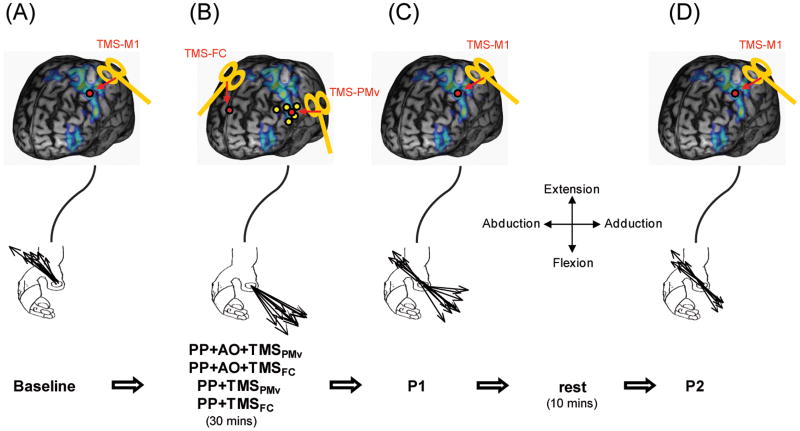

Fig. 1. Experimental design.

A. Baseline. At the beginning, TMS-evoked thumb movements were elicited and their directions calculated from the first-peak acceleration along the two major axes of the movement, extension/flexion and adduction/abduction using an accelerometer. Black lines depict the direction of the individual TMS-evoked thumb movements, in this example extension and abduction. B. Interventions. Immediately following Baseline subjects underwent 4 interventions in separate sessions. (1) Physical practice combined with action observation plus disruptive TMS over PMv (PP+AO+TMSPMv): Subjects performed voluntary thumb movements in the opposite direction to baseline for 30 min, in this case flexion and adduction. The physical practice (PP) was combined with observing a video displaying thumb movements in the same direction (action observation, AO). During this training single TMS pulses were delivered over PMv. (2) Physical practice combined with action observation plus disruptive TMS over frontal cortex (PP+AO+TMSFC): This session is identical to the previously described except that TMS was delivered over the mid-frontal cortex (Fz in the 10-20 EEG-coordinate system). (3) Physical practice with disruptive TMS over PMv (PP+TMSPMv): This session is similar to the PP+AO+TMSPMV condition except that subjects did not perform action observation. (4) Physical practice with disruptive TMS over FC (PP+TMSFC): Subjects performed PP without AO, as in PP+TMSPMV, but the TMS was applied over FC as done during the PP+AO+TMSFC session. C. Post1 (P1). The direction of TMS-evoked thumb movements was determined identically as done at Baseline. D. Post 2 (P2). Following a break of 10 min, the direction of TMS-evoked thumb movements was determined again. Red dots represent the TMS location sites for each study phase. Yellow dots represent previously established fMRI-activated coordinates in PMv during action observation studies (see methods).

Physical Practice + Action Observation + TMS over PMv (PP+AO+TMSPMV)

Physical practice (PP) consisted of performance of voluntary thumb movements at 1Hz in the opposite direction to the TMS-evoked baseline direction for 30 minutes (3 blocks of 10 min each separated by a 2 min rest period). For example, if the principal baseline direction was extension and abduction, then the subject was instructed to perform repetitive flexion and adduction movements during training. We instructed the subjects to relax and let the thumb return to its original position after each movement. This was ensured by monitoring on-line EMG, acceleration signals, and providing verbal feedback when needed. Action observation (AO) consisted of watching a video displaying the hand of a volunteer performing the same motor training task at 1Hz and in the same direction to the physically practiced. We instructed participants to synchronize and match the direction of their voluntary thumb movements with the movements observed in the video. Subjects also wore a pair of goggles with a cover below the eyes to ensure that subjects could not observe their own hand. Disruptive stimulation consisted of applying single TMS pulses over PMv triggered by the onset of each voluntary thumb movement. The onset of movement was determined by the thumb accelerometer and defined as a thumb movement acceleration of at least 0.65cm/s2 along the vertical axis. This resulted in stimulation being delivered at approximately 1Hz frequency at the beginning of each voluntary thumb movement as previously done in earlier work (Bütefisch et al., 2004).

Physical Practice + Action Observation + TMS over Frontal Cortex (PP+AO+TMSFC)

This session was identical to the previously described except that TMS was delivered over the midline of the frontal cortex to the site corresponding to Fz in the 10-20 EEG coordinate system (Lagerlund et al., 1993). Fz is standard control site used in UDP studies because of its lack of involvement in motor memory formation (Cohen et al., 1997) and lack of fMRI activation during similar motor training (Morgen et al., 2004a; Morgen et al. 2004b).

Following the interventions in each of the sessions we reassessed the TMS-evoked thumb movement directions as done during baseline (post1). A change in the TMS-evoked thumb movement direction is referred to as UDP and interpreted as a reflection of motor memory formation. After this, subjects rested for 10 minutes followed by another 65 TMS pulses applied over the M1 hot spot (post2) to assess the longevity of the effects. At the end of each session subjects reported their alertness, attention, and perceived pain of TMS using a self-scored visual analogue scale (Stefan 2005).

Controls

Upon completion of the initial experiment all subjects returned and completed two more subsequent control sessions in a randomized-cross over design. Testing and recording procedures were identical to the previous sessions.

Physical Practice +TMS over PMv (PP+TMSPMV)

Similar to the PP+AO+TMSPMV conditions, subjects performed PP and received TMS over PMv synchronized to each thumb movement, but they did not perform video observation. Here, subjects observed a blue dot blinking at 1Hz to cue the subjects to perform the voluntary movements. This control was designed to determine whether TMS over PMv alone had a disruptive effect on UDP induced by PP alone.

Physical Practice + TMS over Frontal Cortex (PP+TMSFC)

In this session subjects only performed PP without AO, as in PP+TMSPMV, but the TMS was applied over the frontal cortex as done during the PP+AO+TMSFC session.

These controls were necessary to ensure that any reduction in UDP changes with disruptive stimulation over PMv was due to the elimination of the contribution of action observation and not due to TMS stimulation affecting the contribution of physical practice.

PMv Stimulation Site Determination

To determine the PMv stimulation location for each individual subject, we first performed a functional MRI study in all participants. Subjects laid in the scanner with an fMRI compatible accelerometer (Kistler Instruments, Amherst, NY) attached to their right thumb. The movement period of the task involved subjects flexing their thumb while observing a video displaying congruent thumb movements. The video showed a thumb of a volunteer flexing at a rate of 1Hz. Participants were instructed to move their thumb at the same rate and time as in the video. The rest period involved subjects remaining motionless while observing a still picture of a thumb. The task lasted 5 minutes with the movement and rest periods alternating every 30 seconds.

To determine the peak activation area of PMv for each participant we compared activation during performance of PP+AO relative to rest (see Supplementary Methods for further details of the fMRI study). We then overlaid the individual peak activation of the PMv area to previously published PMv regions (Binkofski et al., 1999; Buccino et al., 2001; Buccino et al., 2004a; Ehrsson et al., 2000; Ehrsson et al., 2001; Grefkes et al., 2002; and Kuhtz-Buschbeck et al., 2001). The coordinates from these studies were transferred from MNI coordinates to each subject's brain space using MRIcroN. The area of largest individual activation that approximated the previously described PMv coordinates was chosen as the target for TMS over PMv used in conditions 1 and 3 (Fig. 1).

To determine whether the PMv stimulation site chosen with the above procedure was also activated during the PP alone session, we performed a 2nd fMRI session similar to the previously described. The only difference was that in this session subjects performed the physical practice without video observation. Movements were cued as in the controls sessions (see above). The images were analyzed as previously described (see also Supplementary Methods).

Data Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the change in direction of TMS-evoked movements as a function of the different interventions. This was determined as the percentage of movements falling within the training target zone (TTZ), defined as a window of +/− 20 degrees around the training direction (i.e. 180 degrees opposite to the baseline TMS-evoked movements), before and after each intervention. The secondary outcome measures included: 1) Relative angular distance (RAD), defined as the mean TMS-evoked movement direction at baseline subtracted from the mean TMS-evoked movement direction after training; (2) Corticomuscular excitability, calculated by measuring MEP amplitudes in the agonist and antagonist muscles of the trained movement direction. To describe the net effects of training on corticomuscular excitability, we calculated the ratio between post-training and pre-training MEP amplitudes for the agonist and antagonist muscles.

To assess the consistency of training across conditions we measured the compound acceleration of the voluntary training movements, defined as the mean magnitude of the first peak acceleration in the extension/flexion direction regardless of direction. In addition, we calculated angular variability (Stephan et al., 2008; Galea and Celnik, 2009) that depicts the movement direction dispersion during training, radial distance which indicates the mean length of each thumb movement, and the angular difference between TMS-evoked movement directions at baseline and training.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the primary and secondary outcome measures using separate polynomial nested repeated measures ANOVA (ANOVARM) with factors TIME (baseline, post-intervention 1, post-intervention 2) and SESSION (PP+AO+TMS-FC, PP+AO+TMS-PMv, PP+TMS-FC, PP+TMS-FC). When appropriate we performed post hoc testing using paired t-tests. To analyze general measurements of baseline corticomotor excitability (motor threshold, TMS stimulus intensity, MEPagonist and MEPantagonist amplitudes), attention, fatigue, and motor training kinematics (angular dispersion, compound acceleration, radial distance, and angular difference between TMS-evoked movement direction at baseline and during voluntary motor training), we employed separate ANOVARM with factor SESSION (PP+AO+TMS-FC, PP+AO+TMS-PMv, PP+TMS-FC, PP+TMS-FC). To determine changes in the MEPPost-Intervention/Baseline ratio between the agonist and antagonist muscles we performed a pre-planned paired t-test analysis only in the conditions that showed significant difference for the primary outcome measure, and corrected for multiple comparisons when appropriate. All data is presented as mean ± SEM.

To determine fMRI activation differences in the stimulated PMv site between sessions, we created a 6mm ROI centered on the PMv trajectory and analyzed the activation intensity using a paired t-test.

Results

Summary

All subjects completed the study without adverse events. fMRI activation of the stimulated PMv site during the PP+AO condition was significantly higher than during the PP alone condition (p=0.03). TMS-evoked movements at baseline and training kinematics were consistent across sessions. All interventions showed training-induced changes in TMS-evoked movement directions. However, this effect was most prominent in the PP+AO+TMSFC session immediately after training (p1) and 20 minutes later (p2) relative to all other interventions. Training-induced effects in PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv sessions were comparable.

Training characteristics

Subjects' ratings of attention, fatigue, and discomfort were similar across all sessions (Table 1).

Table 1. Psychological measures.

Values represent subjects' reported alertness and attention using a self-scored visual analog scale (VAS): 1 represents the poorest attention, least fatigue, and least discomfort; and 7 represents the maximal attention, ad most fatigue, and most discomfort. Training kinematics. Distance from baseline reflects the mean angular difference between movement directions at baseline and training. The compound acceleration describes the mean acceleration of each thumb movement during training regardless of direction. Angular variability depicts the movement direction dispersion during training. The radial distance indicates the mean length of each thumb movement during training. All psychological and kinematic measures were similar across sessions. Data are means ± SEM.

| Parameter | PP+AO+TMSFC | PP+AO+TMSPMv | PP+TMSFC | PP+TMSPMv | ANOVARM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsychologicalMeasures | |||||

| Attention | 5.44±0.50 | 5.56±0.23 | 5.80±0.39 | 5.90±0.66 | p=0.75 |

| Fatigue | 2.67±0.52 | 3.00±0.38 | 2.30±0.33 | 2.00±0.94 | p=0.30 |

| Discomfort | 1.00±0.00 | 1.67±0.32 | 1.20±0.13 | 1.33±0.60 | p=0.21 |

| Training Kinematics | |||||

| Compound Acceleration (cm/s2) | 1.62±0.15 | 1.84±0.27 | 1.50±0.14 | 1.67±0.21 | p=0.44 |

| Angualar Variance (degrees) | 14.01±1.54 | 13.56±1.60 | 11.44±1.30 | 14.39±0.2.21 | p=0.36 |

| Distance from Baseline (degrees) | 138.12±4.41 | 125.89±5.73 | 127.05±4.86 | 129.72±6.27 | p=0.38 |

| Radial Distance (cm) | 2.02±0.18 | 2.32±0.27 | 1.80±0.16 | 2.08±0.19 | p=0.11 |

Motor training kinematics were comparable across all training interventions for compound acceleration, angular variance, radial distance, and the angular difference between TMS-evoked movement directions at baseline and training (Table 1). On average the EMG activity duration of each thumb movement was 137.51±15.38 ms and the TMS pulse was delivered at 36.78±6.40 ms into the onset of the EMG activity.

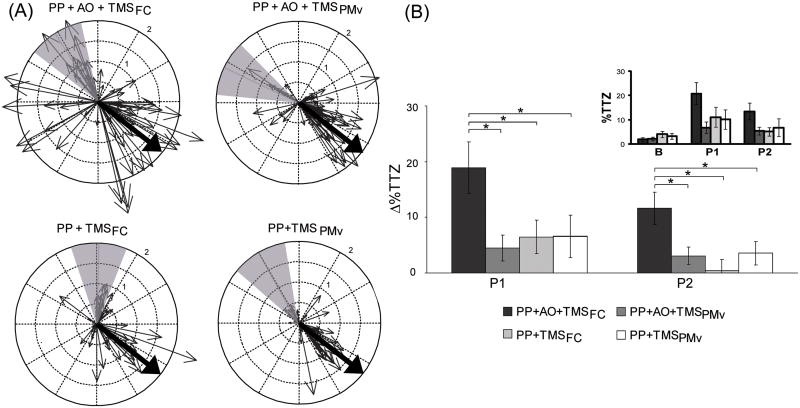

Effects of disruptive TMS on use-dependent plasticity resulting from PP+AO

ANOVARM revealed a significant effect of time (F(2,18)=8.09, p<0.01), session (F(3,27)=3.08, p<0.05), and time by session interaction (F(6,54)=3.62, p<0.05) for the percent of movements falling within the training target zone (TTZ), the primary outcome measure (Fig. 2). Given the lack of significant differences in the percent of movements falling in TTZ at baseline (F(3,27)=0.97, p=0.41), we evaluated the change in the percentage of movements falling with the TTZ relative to baseline (ΔTTZ). ANOVARM showed a significant main effect for session for ΔTTZ (F(3,27)=7.23, p<0.05). Post hoc paired t-tests revealed that at p1 ΔTTZ was significantly larger than 0 in all sessions (PP+AO+TMSFCt(9)=4.12, p<0.01; PP+AO+TMSPMv t(9)=1.93, p<0.05; PP+TMSFC t(9)=2.16, p<0.05; PP+TMSPMv t(9)=1.74, p<0.05). This effect was similar at p2 in all sessions except for PP+TMSFC(PP+AO+TMSFC t(9)=3.94, p<0.01; PP+AO+TMSPMv t(9)=1.96, p<0.05; PP+TMSPMv t(9)=1.67, p=0.07). In addition, two-tailed paired t-tests post hoc showed that PP+AO+TMSFC effects on ΔTTZ were significantly larger in p1 and p2 relative to all other sessions (Table 2). Importantly, there were no significant differences in ΔTTZ between PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv for p1 or p2 (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Circle plot of a representative subject showing the distribution of TMS-evoked movement directions for post 1 of each session. Each small arrow represents the direction of one movement and its radial distance (represented by its length in centimeters). The large arrow depicts the average direction of all TMS-evoked movement at baseline (size of the arrow is not to scale). Gray shaded region represents the training target zone (TTZ). (B) Percent of TMS-evoked movements that fell within the training target zone (TTZ) after training relative to baseline (ΔTTZ). PP+AO+TMSFC effects on ΔTTZ were significantly larger in post 1 (P1) and post 2 (P2) relative to all other sessions. There were no significant differences in ΔTTZ between PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv for P1 or P2. This suggests that disruptive stimulation over PMv significantly reduced UDP changes resulting from PP+AO. The small inset shows the percent of TMS-evoked movements that fell within TTZ at baseline (B), post 1 (P1), and post (P2). *p<0.05. Data are means ± SEM.

Table 2. Statistical measures.

P and t scores from post hoc paired t-tests performed on the post1 and post2 values for the PP+AO+TMSFC, PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv sessions for both the change in the percent of movements falling within the training target zone (ΔTTZ) and the relative angular difference (RAD) between post-training and baseline.

| PP+AO+TMS PMv | ΔTTZ PP+TMSFC | PP+TMS PMv | PP+AO+TMS PMv | RAD PP+TMS FC | PP+TMS PMv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post1 | ||||||

| PP+AO+TMS FC | t(9)=2.86, p<0.05 | t(9)=2.98, p<0.05 | t(9)=2.29, p<0.05 | t(9)=3.59, p<0.01 | t(9)=3.56,p<0.01 | t(9)=3.56, p<0.01 |

| PP+AO+TMS PMv | --- | t(9)=-0.61, p=0.56 | t(9)=-0.53,p=0.61 | --- | t(9)=0.03,p=0.98 | t(9)=0.25, p=0.81 |

| PP+TMS FC | --- | --- | t(9)=0.09,p=0.93 | --- | --- | t(9)=-0.35, p=0.73 |

| Post2 | ||||||

| PP+AO+TMS FC | t(9)=2.75, p<0.05 | t(9)=3.80, p<0.01 | t(9)=2.88, p<0.05 | t(9)=2.73, p<0.05 | t(9)=2.58,p<0.05 | t(9)=2.83, p<0.05 |

| PP+AO+TMS PMv | --- | t(9)=0.94, p=0.37 | t(9)=-0.16,p=0.88 | --- | t(9)=-0.01,p=0.10 | t(9)=0.03, p=0.97 |

| PP+TMS FC | --- | --- | t(9)=1.13,p=0.29 | --- | --- | t(9)=-0.04, p=0.97 |

In summary, disruptive stimulation over PMv significantly reduced the percentage of movements falling within the TTZ after training, a parameter indicative of the magnitude of UDP. Specifically, ΔTTZ for the PP+AO+TMSFC session was significantly larger in p1 and p2 relative to all other sessions, whereas there were no significant differences in ΔTTZ between PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv for p1 nor p2.

In addition, given that the angular difference between TMS-evoked movement directions at baseline and training were similar across conditions (F(3,27)=1.39, p=0.27), we determined the effects of the interventions on the angular difference between post-training minus baseline. Unlike the TTZ analysis, the relative angular distance (RAD) gives continuous information about angular changes of the TMS-evoked movement directions. ANOVARM revealed a significant main effect of session (F(3,27)=9.130, p<0.01) and time (F(1,9)=5.318, p<0.05) in RAD. Two-tailed paired t-tests showed that RAD was significantly larger than 0 at p1 in all groups (PP+AO+TMSFC t(9)=6.88, p<0.01; PP+AO+TMSPMv t(9)=4.15, p<0.01; PP+TMSFC t(9)=4.05, p<0.01; PP+TMSPMv t(9)=3.03, p<0.05). This effect was also found at p2 (PP+AO+TMSFC t(9)=4.64, p<0.01; PP+AO+TMSPMv t(9)=9.53, p<0.01; PP+TMSFC t(9)=4.62, p<0.01; PP+TMSPMv t(9)=4.76, p<0.01). Furthermore, two-tailed paired t-tests showed that PP+AO+TMSFC effects on RAD were significantly larger at both p1 and p2 relative to all other interventions (Table 2). Finally, two-tailed pairwise t-tests for RAD were not significantly different between PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv at p1 or p2 (Table 2).

In summary, disruptive stimulation over PMv significantly reduced the change in relative angular direction (RAD). Change in RAD is another parameter that reflects the amount of motor memory formation. RAD was significantly larger for PP+AO+TMSFC relative to all other sessions for both p1 and p2, and was similar between PP+AO+TMSPMv, PP+TMSFC, and PP+TMSPMv for p1 and p2.

Corticomuscular excitability changes associated to training

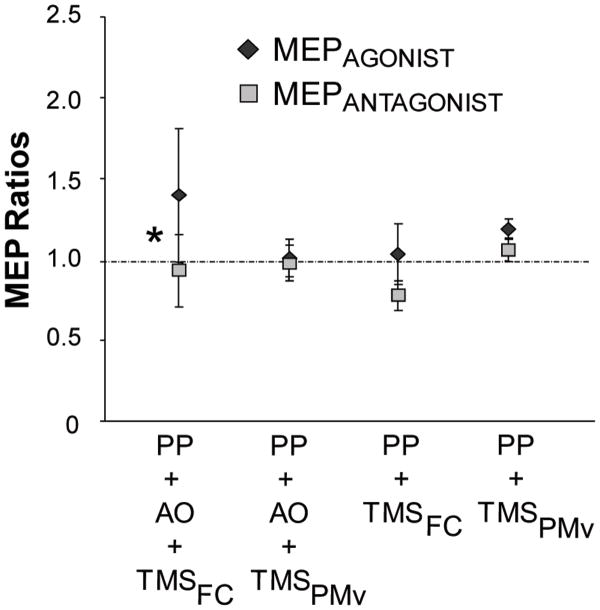

To determine changes in corticomotor excitability we assessed the MEP amplitude ratio (post/pre) for the agonist and antagonist muscles. A two-tailed pairwise t-test revealed a significant difference between the increase in the MEPAGONIST ratio compared with the MEPANTAGONIST ratio at p1 for the PP+AO+ TMSFC session (t(9)=2.27, p<0.05; Fig. 3). This effect was not present in the other conditions.

Fig. 3.

Corticomotor excitability changes as measured by motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitude ratios (Post/Baseline) for the agonist (dark diamonds) and antagonist (light squares) muscles involved in training. After training, only the PP+AO+TMSFC session resulted in a significant increase in the MEPagonist ratio compared with the MEPantagonist ratio at post 1. Data are means ± SEM.

In summary, a differential corticomotor excitability change was seen only in the PP+AO+TMSFC condition.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that disruptive stimulation over PMv reduced the amount of use-dependent plasticity resulting from the combination of physical practice (PP) and action observation (AO). Moreover, the magnitude of plasticity changes found when disrupting PMv in the PP+AO condition was similar to performing the task without AO. This indicates that PMv activation during action observation is functionally relevant to the behavioral performance and not a mere epiphenomenon.

Although skills are acquired through repetitive practice, it has been shown that the mere observation of physical practice, termed action observation, can lead to improvement of performance and UDP (Stefan et al., 2005). It has been suggested that the beneficial effect of AO on performance is due to the merging of information from two anatomically different pathways onto M1 (Celnik et al., 2006; Stefan et al. 2008). One route provides input from the physical execution of movements via connections between dorsal premotor cortex (PMd) and/or Supplementary motor areas (SMA) and M1 (physical practice pathway). The second route provides input from the observation of movements via connections between PMv and M1 (action observation pathway). When these two pathways converge they can potentially reinforce one another in inducing qualitatively similar UDP changes in M1 (Stefan et al., 2005) thus enhancing what either component could do alone. This hypothesis is in line with previous work showing that when AO is combined with congruent PP, the training effects are quantitatively enhanced beyond what the linear summation of the effects of AO or PP alone can do for both healthy subjects (Stefan et al., 2008; Celnik et al., 2006) and stroke patients (Celnik et al., 2008). This hypothesis is further supported by prior evidence showing that the excitability of connections between PMv and M1 are influenced by AO (Koch et al., 2010; Lago et al., 2010).

In this study, we were interested in exploring whether activation of PMv is crucial for the contribution AO has on UDP changes in M1 that underlie motor memory formation. We speculate that disruption of PMv may be interrupting part of the action observation pathway that allows AO to facilitate UDP occurring in M1. This information is important not only for motor exercises and rehabilitation, but also because determining the functional role of PMv activation associated to AO can have significant implications in understanding the actions and intentions of others (Iacoboni et al. 2005), imitation learning (Iacoboni et al. 1999), and disorders like autism (Cattaneo et al., 2009).

Previous work has shown that repetitive TMS (rTMS) at 1Hz can be used to transiently inactive different cortical areas to induce a “virtual lesion” (Chen et al., 1997). In addition, delivering TMS in synchrony with thumb movements over the involved primary motor cortex in a similar paradigm successfully interfered with motor memory formation (Bütefisch et al., 2004). Here, we used fMRI-guided rTMS to disrupt the activation of PMv during performance of PP and AO. We found that disruptive rTMS reduced the change in angular direction and the percent of movements following the training direction relative to performance of PP+AO with disruptive rTMS over a control site (orbitofrontal cortex, FC). This reduction in movement direction changes is interpreted as interference of UDP changes that underlie motor memory formation. In addition, we found that in both control groups where PP was performed without AO during disruptive stimulation over PMv or FC, the effect of PP on UDP changes was similar to PP+AO with disruptive stimulation over PMv. These suggest that the contribution of AO to UDP was canceled out by disruptive rTMS over PMv resulting in similar gains as performing PP alone.

Importantly, our controls showed that rTMS over PMv did not interfere with UDP induced by PP alone. We reasoned that if disruptive stimulation over PMv was interfering with the physical practice contribution to plasticity changes then the magnitude of memory formation during PP+TMSPMv should be smaller than PP+TMSFC. However, we found that this was not the case; in fact, the effects of training in both control sessions were similar to PP+AO+TMSPMV.

Given that certain subgroups of PMv neurons have been shown to be involved in grasping and reaching movements (Hoshi et al., 2007; Kurata et al., 2002; Shadmehr et al., 2005; Fogassi et al., 2001), one might have expected that disruption of PMv could have decreased UDP changes in M1 resulting from PP simply due to interference of motor performance. However, our behavioral task does not require reaching toward a target or grasping any object, which could explain why disruption of PMv had a similar effect on UDP induced by PP alone as disruption of FC. Furthermore, it has been shown that although premotor areas are activated during finger flexion or extension movements, UDP evoked by 30 min of voluntary thumb training is associated with fMRI activation changes in contralateral M1, S1, and IPL, but not with changes in activation of premotor cortex or inferior frontal gyrus (Morgen et al., 2004a, Morgen et al., 2004b). Additionally, the same study showed that premotor activation during finger flexion and extension, as done in our study, was bilateral. This may be an alternative explanation as to why disrupting only one premotor area had relatively little effect on movement execution. In the current study, the PMv stimulated site chosen when subjects performed PP+AO was not similarly activated when the same subjects performed PP alone. Importantly, our repetitive stimulation over PMv during the physical practice did not affect the kinematics of the thumb movement training. Thus, although PMv has been shown to be involved in finger movements, it appears that this area is not critically responsible in eliciting use-dependent plasticity changes in M1, at least when assessed using our behavioral paradigm. This is supported by other studies showing that disruptive stimulation over other premotor areas such as the pars opercularis of the inferior fronta gyrus (i.e. Broca's area) resulted in an impairment in the imitation of a finger-movement task, but not in the mere execution of the same task (Heiser et al., 2003). Alternatively, it may still be possible that TMS in this paradigm is not disruptive enough to override the PMv role during finger training. Therefore, we interpret that the reduction in UDP changes in M1 during the PP+AO+TMSPMv session was due to a specific interference of the contribution of action observation to UDP and not due to a disruption of the physical practice component.

Importantly, although here we found that disruption of PMv diminishes the contribution of AO to physical practice, other investigations have shown that interfering with M1 or the cerebellum can also affect the beneficial effects of AO to different behaviors (Brown et al., 2009; Petrosini et al., 2007). This current investigation adds to these previous findings, showing here that disrupting PMv can also disturb the action observation pathway in an upstream node to M1.

In addition, similar to previous studies, we also found that large UDP changes in M1 resulting from PP+AO with sham rTMS was associated with a specific change in excitability of the muscles involved in the observation and practice of the task (Bütefisch et al., 2004; Celnik et al., 2005; Stefan et al., 2008). Specifically, the excitability of the agonist muscle cortical representation of the observed/practiced movements increased whereas the antagonist muscle excitability decreased. This training-dependent plasticity, not observed in any of the other sessions, indicates a change in the distribution of neuronal network strength between cortical representations, a mechanism thought to represent the neurophysiological correlate of successful motor memory formation (Bütefisch et al., 2000). We did not find any significant changes in the MEPagonist excitability for the PP with sham rTMS, a finding inconsistent with previous results (Bütefisch et al., 2000; Stefan et al., 2008). This discrepancy may be attributed to the overall low percent of TMS-evoked movement changes. This can be explained by an overall reduction of training effects when the practice is performed with TMS delivered to any part of the head (i.e. non-specific TMS effects during training) or because, unlike previous studies, we did not exclude subjects for having low amounts of plasticity changes.

In the future, it would be important to explore the functional relevance of other cortical regions also believed to be associated with action observation, such as the anterior inferior parietal lobule (IPL) (Buccino et al., 2004; Cattaneo et. al., 2009; Morgen et al., 2004a). Furthermore, it would be interesting to figure out specifically which subset of neurons in the PMv are responsible for the contributions of AO, unfortunately such a level of specificity cannot be tested using noninvasive brain stimulation techniques. However, using direct recordings of extracellular neural activity in patients (Mukamel et al., 2010) during action observation in the same regions explored in the current study could be used to asses more in depth the neurophysiological interactions described here.

In sum, our findings demonstrate that the fMRI-activated areas of PMv during action observation are functionally relevant to task performance, at least for the beneficial effects that AO has over plasticity changes induced by physical practice. Importantly, our results open an opportunity to investigate the use of non-invasive brain stimulation techniques over PMv to enhance the effects of action observation, a strategy that can potentially result in a therapeutic intervention for patients with neurological disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NICHD, NIH (R01 HD053793 and R21 HD060169).

References

- Brass M, Bekkering H, Prinz W. Movement observation affects movement execution in a simple response task. Acta Pshychol (Amst) 2001;106:3–22. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(00)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LE, Wilson ET, Gribble PL. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to the primary motor cortex interferes with motor learning by observing. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21(5):1013–22. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccino G, Binkofski F, Fing GR, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Galeese V, Seitz RJ, Ziolles K, Rizzolatti G, Freund HJ. Action observation activates premotor and parietal areas in a somatotopic manner: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13(2):400–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccino G, Lui F, Canessa N, Patteri I, Lagravinese G, Benuzzi F, Porro CA, Rizzolatti G. Neural circuits involved in the recognition of actions performed by nonconspecifics: an fMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004b;16(1):114–126. doi: 10.1162/089892904322755601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccino G, Vogt S, Ritzl A, Fing GR, Zilles K, Freund HJ, Rizzolatti G. Neural circuits underlying imitation learning of hand actions; an event-related fMRI study. Neuron. 2004a;42:323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkofski F, Buccino G, Posse S, Seitz RJ, Rizzolatti G, Freund H. A fronto-parietal circuit for object manipulation in man: evidence from an fMRI-study. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3276–3286. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bütefisch CM, Khurana V, Kopylev L, Cohen LG. Enhancing encoding of a motor memory in the primary motor cortex by cortical stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(5):2110–2116. doi: 10.1152/jn.01038.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bütefisch CM, Davis BC, Wise SP, Sawaki L, Kopylev L, Classen J, Cohen LG. Mechanisms of use-dependent plasticity in the human motor cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(7):3661–3665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050350297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo L, Rizzolatti G. The mirror neuron system. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(5):557–60. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff C, Celnik P, Wassermann EM, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1389–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celnik P, Stefan K, Hummel F, Duque J, Classen J, Cohen LG. Encoding a motor memory in the older adult by action observation. Neuroimage. 2006;29(2):677–684. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celnik P, Webster B, Glasser DM, Cohen LG. Effects of action observation on physical training after stroke. Stroke. 2008;39(6):1814–1820. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen J, Liepert A, Wise SP, Hallet M, Cohen LG. Rapid plasticity of human cortical movement representation induced by practice. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1117–1123. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LG, Celnik P, Pascual-Leone A, Corwell B, Falz L, Dambrosia J, Honda M, Sadato N, Gerloff C, Catalá MD, Hallett M. Functional relevance of cross-modal plasticity in blind humans. Nature. 1997;389(6647):180–183. doi: 10.1038/38278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MG, Humphreys GW, Castello U. Motor facilitation following action observation: a behavioural study in prehensile action. Brain Cogn. 2003;53:495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrsson HH, Fagergren E, Forssberg H. Differential fronto-parietal activation depending on force used in a precision grip task: an fMRI study. J Neurophsiol. 2001;85:2613–2623. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrsson HH, Fagergren A, Jonsson T, Westling G, Johansson RS, Forssberg H. Cortical activity in precision- versus power-grip tasks: an fMRI study. J Neurophsiol. 2000;83:528–536. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.1.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Pavesi G, Rizzolatti G. Motor facilitation during action observation: a magnetic stimulation study. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:2608–2611. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogassi L, Gallese V, Buccino G, Craighero L, Fadiga L, Rizzolatti G. Cortical mechanism for the visual guidance of hand grasping movements in the monkey: A reversible inactivation study. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 3):571–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea JM, Celnik P. Brain polarization enhances the formation and retention of motor memories. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:294–301. doi: 10.1152/jn.00184.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C, Weiss PH, Zilles K, Fink GR. Crossmodal processing of object features in human anterior intraparietal cortex: an fMRI study implies equivalencies between humans and monkeys. Neuron. 2002;35(1):173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00741-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari R, Forss N, Avikainen S, Kirveskari E, Salenius S, Rizzolatti G. Activation of human primary motor cortex during action observation: a neurmagnetic study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15061–15065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser M, Iacoboni M, Maeda F, Marcus J, Mazziotta JC. The essential role of Broca's area in imitation. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17(5):1123–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes CM, Foster CL. Motor learning by observation: evidence from a serial reaction time task. Q J Exp Psychol A. 2002;55:593–607. doi: 10.1080/02724980143000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E, Tanji J. Distinctions between dorsal and ventral premotor areas: anatomical connectivity and functional properties. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;2:234–42. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Molnar-Szakacs I, Gallese V, Buccino G, Mazziotta JC, Rizzolatti G. Grasping the intentions of others with one's own mirror neuron system. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Woods RP, Brass M, Bekkering H, Mazziotta JC, Rizzolatti G. Cortical mechanisms of human imitation. Science. 1999;286:2526–2528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Versace V, Bonnì S, Lupo F, Lo Gerfo E, Oliveri M, Caltagirone C. Resonance of cortico-cortical connections of the motor system with the observation of goal directed grasping movements. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(12):3513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhtz-Buschbeck JP, Ehrsson HH, Forssber H. Human brain activity in the control of fine static precision grip forces: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:392–390. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata K, Hoshi E. Movement-related neuronal activity reflecting the transformation of coordinates in the ventral premotor cortex of monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88(6):3118–32. doi: 10.1152/jn.00070.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerlund TD, Sharbrough FW, Jack CR, Jr, Erickson BJ, Strelow DC, Cicora KM, Busacker NE. Determination of 10-20 system electrode locations using magnetic resonance image scanning with markers. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;86(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(93)90062-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lago A, Koch G, Cheeran B, Márquez G, Sánchez JA, Ezquerro M, Giraldez M, Fernández-del-Olmo M. Ventral premotor to primary motor cortical interactions during noxious and naturalistic action observation. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(6):1802–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattar AG, Gribble PL. Motor learning by observation. Neruon. 2005;46:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgen K, Kadom N, Sawaki L, Tessitore A, Ohayon J, Frank J, McFarland H, Martin R, Cohen LG. Kinematic specificity of cortical reorganization associated with motor training. Neuroimage. 2004a;21(3):1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgen K, Kadom N, Sawaki L, Tessitore A, Ohayon J, McFarland H, Frank J, Martin R, Cohen LG. Training-dependent plasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2004b;127(Pt 11):2506–2517. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel R, Ekstrom AD, Kaplan J, Iacoboni M, Fried I. Single-neuron responses in humans during execution and observation of actions. Current Biology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.045. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani N, Hari R. Temporal dynamics of cortical representation for action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:913–918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosini L. “Do what I do” and “do how I do”: different components of imitative learning are mediated by different neural structures. Neuroscientist. 2007;13(4):335–48. doi: 10.1177/10738584070130040701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini PM, Barker AT, Berardelli A, Caramia MD, Caruso G, Cracco RQ, Dimitrijević MR, Hallett M, Katayama Y, Lücking CH, et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91(2):79–92. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Wise SP. The computational neurobiology of reaching and pointing: a foundation for motor learning. In: Sejnowski TJ, Pogio TA, editors. Computational Neuroscience. The MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Classen J, Celnik P, Cohen LG. Concurrent action observation modulates practice-induced motor memory formation. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(3):730–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Cohen LG, Duque J, Mazzocchio R, Celnik P, Sawaki L, Ungerleider L, Classen J. Formation of a motor memory by action observation. J Neurosci. 2005;25(41):9339–9346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2282-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinter A, Perruchet P. Implicit motor learning through observational training in adults and children. Mem Cognit. 2002;30:256–261. doi: 10.3758/bf03195286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.