Abstract

Jasmonates, i.e., jasmonic acid (JA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA), are signaling hormones that regulate a large number of defense responses in plants which in turn affect the plants’ interactions with herbivores and their natural enemies. Here, we investigated the effect of jasmonates on the emission of volatiles in the American cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, at different levels of biological organization from gene expression to organismal interactions. At the molecular level, four genes (BCS, LLS, NER1, and TPS21) responded significantly to gypsy moth larval feeding, MeJA, and mechanical wounding, but to different degrees. The most dramatic changes in expression of BCS and TPS21 (genes in the sesquiterpenoid pathway) were when treated with MeJA. Gypsy moth-damaged and MeJA-treated plants also had significantly elevated expression of LLS and NER1 (genes in the monoterpene and homoterpene biosynthesis pathways, respectively). At the biochemical level, MeJA induced a complex blend of monoterpene and sesquiterpene compounds that differed from gypsy moth and mechanical damage, and followed a diurnal pattern of emission. At the organismal level, numbers of Sparganothis sulfureana moths were lower while numbers of parasitic wasps were higher on sticky traps near MeJA-treated cranberry plants than those near untreated plants. Out of 11 leaf volatiles tested, (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, linalool, and linalool oxide elicited strong antennal (EAG) responses from S. sulfureana, whereas sesquiterpenes elicited weak EAG responses. In addition, mortality of S. sulfureana larvae increased by about 43% in JA treated cranberry plants as compared with untreated plants, indicating a relationship among adult preference, antennal sensitivity to plant odors, and offspring performance. This study highlights the role of the jasmonate-dependent defensive pathway in the emissions of herbivore-induced volatiles in cranberries and its importance in multi-trophic level interactions.

Keywords: methyl jasmonate, jasmonic acid, herbivore-induced plant volatiles, Sparganothis sulfureana, electroantennograms, multi-trophic interactions

Introduction

Plants can sometimes change their phenotype after herbivore feeding damage by becoming more protected from future enemy attacks (Karban and Baldwin, 1997; Walling, 2000; Heil, 2010). These induced phenotypic changes can reduce the performance of herbivores or alter their behavior, i.e., reduce the herbivore’s feeding or oviposition on plants (Agrawal, 1998; Denno et al., 2000; De Moraes et al., 2001; Kessler and Baldwin, 2001; Van Zandt and Agrawal, 2004; Viswanathan et al., 2005), and can thus be classified as direct defenses if they provide a fitness benefit to plants (Agrawal, 1998, 2000). They can also indirectly defend plants by changing the behavior of the herbivores’ natural enemies (Price et al., 1980). One such indirect defense is the emission of volatiles – so-called herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) – that attract predators and parasitoids of insect herbivores to the attacked plant (Turlings et al., 1990; Vet and Dicke, 1992; Dicke and Vet, 1999). Manipulation of these defensive traits in plants can serve as a natural pest control tactic in agriculture (Thaler, 1999a; Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2012).

An important signaling pathway involved in the induction of plant defenses, including HIPV emissions, is the octadecanoid pathway (Karban and Baldwin, 1997; Arimura et al., 2005). In many plants, activation of the octadecanoid pathway by herbivore feeding may lead to increased production of the plant growth regulator, jasmonic acid (JA) (Farmer et al., 1992; Staswick and Lehman, 1999), which in turn can elicit multiple direct and indirect defenses in plants (Karban and Baldwin, 1997). For example, increases in HIPV emissions similar to those induced by insect feeding have been reported in response to exogenous applications of jasmonates, i.e., JA or its volatile methyl ester methyl jasmonate (MeJA), in many plant species including gerbera, Gerbera jamesonii Bolus (Gols et al., 1999), cotton, Gossypium hirsutum L. (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2001), Manchurian ash, Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr. (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2006), and sacred datura, Datura wrightii Regel (Hare, 2007).

Activation of the octadecanoid pathway by jasmonate treatment is known to affect the preference and performance of herbivores on plants. Thaler et al. (2001), for example, found fewer caterpillars, flea beetles, aphids, and thrips on tomato plants that were sprayed with JA. Manduca quinquemaculata Haworth oviposition was reduced when Nicotiana attenuata Torr ex. S. Watts plants were treated with MeJA (Kessler and Baldwin, 2001). Similarly, Bruinsma et al. (2007) showed that two species of cabbage white butterflies, Pieris rapae L. and P. brassicae L., laid fewer eggs on JA-treated Brussels sprouts, Brassica oleracea L., plants compared to untreated plants. Pieris rapae also preferred untreated leaves over JA-treated leaves of black mustard plants, Brassica nigra L., for oviposition (Bruinsma et al., 2008). Jasmonate-induced changes can also affect members of higher trophic levels. For example, JA treatment increased parasitism of caterpillars in tomato fields (Thaler, 1999b), but negatively affected predatory hoverflies due to a decrease in prey (aphid) abundance (Thaler, 2002). JA or MeJA also induced the emission of plant volatiles that attracted predatory mites (Dicke et al., 1999; Gols et al., 2003).

Studies that integrate multiple research approaches, such as gene expression, metabolite induction, and ecological interactions, are needed for a better understanding of plant interactions with arthropods across different levels of biological organization (Zheng and Dicke, 2008). Previously, we showed that gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar L. (Lep., Lymantriidae), larval feeding, and MeJA induce emissions of several monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes in a perennial ericaceous crop, the American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011). In the present study, we linked volatile induction with transcriptional induction and organismal level interactions by investigating the effects of jasmonates on the up-regulation of several key terpene biosynthesis genes, induced volatile emissions, and the preference-performance of a polyphagous herbivore, Sparganothis sulfureana Clemens (Sparganothis fruitworm; Lep., Tortricidae), in cranberries. Sparganothis sulfureana is an important pest of cranberries in the United States (USA); in spring, the overwintered first instar larvae feed on foliage, adults emerge in late spring to mid-summer, and in June to early July second generation larvae feed on foliage and burrow into developing fruit (Beckwith, 1938; Averill and Sylvia, 1998). Specifically, we conducted studies to: (1) determine the effects of MeJA, gypsy moth larval feeding, and mechanical wounding on expression of eight genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis; (2) compare the volatile emissions of cranberries in response to MeJA application, gypsy moth feeding, and mechanical wounding, and investigate the diurnal pattern of volatile emissions; (3) examine the response of key herbivores (S. sulfureana and leafhoppers) and natural enemies [hoverflies (Dip., Syrphidae), minute pirate bugs (Hem., Anthocoridae), spiders (Araneae), and parasitic wasps (Hymenoptera)] to MeJA application on cranberry plants; (4) test the effect of JA-treated cranberry foliage on S. sulfureana larval mortality; and, (5) investigate the electrophysiological response of S. sulfureana antennae (EAG) to various cranberry leaf volatiles.

Materials and Methods

Plants and insects

Cranberries are propagated clonally and grow from single shoots by producing new uprights and runners. Cranberries, V. macrocarpon var. Stevens, were grown from rooted cuttings in 10 cm pots in a greenhouse (22 ± 2°C; 70 ± 10% RH; 15:9 L:D) at the Rutgers P. E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research and Extension (Chatsworth, NJ, USA). Three cuttings were rooted per pot. Plants were allowed to grow in the greenhouse for at least a year before being used in experiments, and were fertilized biweekly with PRO-SOL 20-20-20 N-P-K All Purpose Plant Food (Pro Sol Inc., Ozark, AL, USA) at a rate of 165 ppm N and watered daily. At the time of bioassays, plants from each rooted cutting contained 3–5 uprights and runners. Runners were pruned as needed, and all plants were at the vegetative stage and insect-free when used in experiments.

Lymantria dispar caterpillars and Sparganothis sulfureana adults and caterpillars were obtained from a laboratory colony maintained at the Rutgers Marucci Center. Caterpillars were reared on a wheat germ diet (Bell et al., 1981) in 30 ml clear plastic cups at 24 ± 1°C, 65% RH, and 14:10 L:D. Field-collected caterpillars were added yearly to the laboratory colony.

Treatment applications

Plants in each pot were bagged with a spun polyester sleeve (Rockingham Opportunities Corp., Reidsville, NC, USA) and then subjected to one of the following treatments:

-

(1)

Jasmonate treatment: potted plants were sprayed with 1 ml of a 1 mM JA or MeJA solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in 0.4% acetone or 0.1% Tween 20, respectively. Treated plants were used for bioassays (gene expression, volatile collections, and field experiments, see below) ∼16 h after jasmonate application (unless otherwise stated); this time period was sufficient to induce a volatile response from cranberry leaves in previous studies (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011).

-

(2)

Caterpillar treatment: cranberry leaves were damaged by third–fourth instar gypsy moth caterpillars. Four or eight caterpillars were placed on plants and allowed to feed for 2 days before used in bioassays (gene expression and volatile collections); this amount of feeding time by gypsy moth was sufficient to induce a volatile response from cranberry leaves (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011).

-

(3)

Mechanical treatment: mechanical damage was inflicted for 2 days by cutting the tips of 40 leaves (20 leaves were mechanically damaged on day 1 and 20 leaves on day 2) with scissors to simulate the amount of leaf area removed by gypsy moth caterpillars. Following, plants were used for gene expression and volatile collections.

-

(4)

Control treatment: plants were either sprayed with 1 ml of distilled water with 0.4% acetone, 0.1% Tween 20, or received no treatment.

Bags were opened just prior to, and closed soon after, treatment.

Gene expression analysis

Leaves were harvested from jasmonate (MeJA)-treated, caterpillar-damaged, mechanically wounded, and control (Tween) plants (N = 3 individual plants or biological replicates per treatment). We used eight rather than four gypsy moth caterpillars in these studies because this herbivore density induces a stronger volatile response in cranberries (see Results). We also harvested undamaged leaves from plants upon which gypsy moths fed and from mechanically wounded plants (systemic response). All samples were collected at 10:00. RNA was immediately extracted from the harvested leaves using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. The total RNA was eluted in 100 μl sterile dH2O and quantified using the ND-1000 Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Products; Wilmington, DE, USA). The cDNA was synthesized using 100 ng of RNA per reaction and the Superscript VILO cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The genes targeted for real-time PCR and the primers used for each are listed in Table 1. The eight genes were selected for expression analysis based partly on published reports of terpenoid biosynthesis gene induction when jasmonate treated or in response to herbivores and partly on our own previous work on the volatiles that cranberry plants emit (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011). These include (−)-β-caryophyllene synthase (BCS), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FDS), R-linalool synthase (LLS), (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase (MDS), (3S,6E)-nerolidol synthase (NER1), phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK), terpene 1,8-cineole synthase (TPS), and α-humulene/β-caryophyllene synthase (TPS21). Actin (ACT) and RNA Helicase 8 (RH8) were used as endogenous controls. The gene sequences were selected from an assembled total genome sequence of cranberry (Georgi et al., 2013 and unpublished). Each target gene sequence was identified by homology to published sequences from other plant species. The primers were designed using the predicted coding sequence of each gene and the Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA). Real-time PCR reactions were set up using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s directions and run on an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR machine. Thermocycling conditions were 50°C–2 min, 95°C–10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95°C–15 s, 60°C–1 min with melt curve set at 95°C–15 s, 60°C–1 min, 95°C–30 s, 60°C–15 s. There were three biological replicates (individual plants) of each sample and three technical replicates were run for each biological replicate. The technical replicates for each biological replicate were averaged. Relative expression levels were calculated by the ΔΔCT method using the DataAssist 3.0 software package (Applied Biosystems) and using ACT and RH8 to normalize the expression.

Table 1.

Targets used for real-time qPCR, enzyme commission (EC) numbers and primer sequences.

| Target (abbreviation) | EC number | Real-time F primer | Real-time R primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FDS) | 2.5.1.10 | CGAGGTCAGCCATGTTGGTA | CCATCATTTGCAGCAATCAAA |

| (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase (MDS) | 1.17.7.1 | GCACAGGCGTTACTTCGATTT | CCCTCTTTTTGGATTGGCAAT |

| Phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK) | 2.7.4.2 | TTCCCTTCCACCGTTTACATCT | AGGCTTGCGAGTTTCTGAATTT |

| Terpene 1,8-cineole synthase (TPS) | 4.2.3.108 | GGTGGGATATAACTGCAATGGAA | TGAAAAGAGCAAGGAAGCAAATC |

| (−)-β-Caryophyllene synthase (BCS) | 4.2.3.57 | TCCGGTGGTTACAAAATGCTT | CACCAAATCCCCCATGACA |

| R-Linalool synthase (LLS) | 4.2.3.26 | GGGCAAGTTTGTGCAATGC | GGCAACTGCCCAGAAGCA |

| α-Humulene/β-caryophyllene synthase (TPS21) | 4.2.3. | TCCGGTGGTTACAAAATGCTT | CACCAAATCCCCCATGACA |

| (3S,6E)-nerolidol synthase (NER1) | 4.2.3.48 | GGGCAAGTTTGTGCAATGC | GGCAACTGCCCAGAAGCA |

| Actin (ACT) | – | TTCACCACCACGGCTGAAC | AGCCACGTATGCAAGCTTTTC |

| RNA Helicase-Like 8 (RH8) | 3.6.4.13 | TGCCAAGATGCTTCAAGATCA | GCATGCACCATTCCGAAAAT |

Headspace collection

Volatiles emitted from cranberry plants that were either damaged by four or eight gypsy moth caterpillars, treated with MeJA, or left undamaged were collected using a push-pull volatile collection system (Tholl and Röse, 2006; Rodriguez-Saona, 2011) in a greenhouse (under conditions described above). The system consisted of four 4 L glass chambers (Analytical Research Systems, Inc., Gainesville, FL, USA). The chambers had a guillotine-like split plate with a hole in the center at the base that closed loosely around the stem of the plant. Incoming purified air entered each chamber at 2 L min−1 and was pulled through a filter trap containing 30 mg of Super-Q adsorbent (Alltech; Nicholasville, KY, USA) with a vacuum pump at 1 L min−1. Volatile collections were initiated at 10:00. After 4 h of volatile collection, fresh weight of plants was measured to account for differences in plant size. Each treatment was replicated four times.

To determine the diurnal pattern of emissions, volatiles were collected from MeJA-treated at five different times of the day (06:00–10:00, 10:00–14:00, 14:00–18:00, 18:00–22:00, and 22:00–06:00). The experiment was replicated three times.

Volatile analysis

Collected volatiles were desorbed from the Super-Q traps with dichloromethane (150 μl) and added 400 ng of n-octane (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA) as internal standard (IS). Headspace samples (1 μl aliquots) were injected onto a Hewlett Packard 6890 Series Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a HP-1 column (10 m × 0.53 mm ID × 2.65 μm film thickness; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), with helium flow of 5 ml min−1. The temperature program started at 40°C (1 min hold), and rose at 14°C min−1 to 180°C (2 min hold), then at 40°C min−1 to 200°C (2 min hold). Compounds (relative amounts) were quantified based on comparison of peak areas with that of the IS without FID response factor correction.

Identification of compounds was performed on a Varian 3400 GC coupled to a Finnigan MAT 8230 mass spectrometer (MS) equipped with a MDN-5S column (30 m × 0.32 mm ID × 0.25 μm film thickness; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The temperature program was initiated at 35°C (1 min hold), rose at 4°C min−1 to 170°C, then at 15°C min−1 to 280°C. The MS data were recorded and processed in a Finnigan MAT SS300 data system. The eluted compounds were identified by comparing the mass spectra with those from NIST library spectra and comparison of their retention times to those of commercially available compounds (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011).

Electroantennographic analysis

The relative antennal receptivity of adult males and females of S. sulfureana to 11 synthetic volatile compounds emitted from cranberry plants (this study; Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011) was compared by EAG. The insect head was cut off carefully, and a reference electrode was inserted into its base with a glass capillary filled with physiological saline solution (Malo et al., 2004). The distal end of the antenna was inserted into the tip of the recording glass capillary electrode. EAGs were measured using 5–10 moths of each sex per volatile compound. The signals generated by the antennae were passed through a high-impedance amplifier (NL 1200; Syntech, Hilversum, Netherlands) and displayed on a monitor by Syntech software for processing EAG signals. A stimulus flow controller (CS-05; Syntech) was used to generate a stimulus at 1 min intervals. A current of humidified pure air (0.7 L min−1) was constantly directed onto the antenna through a 10-mm-diameter glass tube. Dilutions of the synthetic compounds were prepared in HPLC-grade hexane to make 10 μg per μl solutions. A standard aliquot (1 μl) of each test dilution was pipetted onto a piece of filter paper (0.5 cm × 3.0 cm; Whatman, No. 1), exposed to air for 20 s to allow the solvent to evaporate, then inserted into a glass Pasteur pipette or sample cartridge, and left for 40 s before applying to antennae. A new cartridge was prepared for each insect. To present a stimulus, the pipette tip containing the test compound was inserted through a side hole located at the midpoint of a glass tube through which humidified pure air flowed at 0.5 L min−1. The duration of stimulus was 1 s. The continuous flow of clean air through the airflow tube and over the preparation ensured that odors were removed immediately from the vicinity. The synthetic compounds (10 μg) were presented in random order. Control stimuli (air or filter paper with hexane) were presented at the beginning and end of each EAG analysis. Synthetic chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Bedoukian Research (Danbury, CT, USA), and the purities were >95% based on the results with GC.

Ecological level analysis

The goal of this field study was to investigate the response of arthropods to MeJA-treated cranberry plants. The experiment was conducted in June–July of 2009 to coincide with S. sulfureana peak flight activity (Averill and Sylvia, 1998), on a commercial cranberry farm located in Chatsworth, New Jersey (39°72′ N, 74°50′ W), using potted cranberry plants (grown as described above). Potted plants were either treated with MeJA or left untreated (controls) (N = 15 pots per treatment). Pots were placed in a 5 × 6 grid pattern within an established cranberry bed (∼2 ha), and were separated by at least 10 m from each other. Treatments were assigned randomly to each location and applied at 17:00. The following morning (08:00), a sticky trap was placed in each pot to monitor abundances of all colonizing arthropods. The sticky traps were 5 cm × 5 cm pieces of green cardboard, covered on both sides (e.g., bi-directional trap) with a thin layer of Tangle-Trap (The Tanglefoot Co., Grand Rapids, MI, USA), and mounted on wooden stakes about 10 cm from the soil, such that the traps were next to but not touching the plants. Traps were left in the field for 48 h, after which they were removed, wrapped in plastic film, and stored in a refrigerator (4°C) for arthropod identification. The entire experiment was replicated three times with a new set of plants each time.

To determine the effects of jasmonate-mediated responses in cranberries on S. sulfureana larval survival, an experiment was conducted in a cranberry bed located at the Rutgers Marucci Center. Plots (60 cm × 60 cm) were treated with JA or left untreated (controls), replicated three times, and separated by 60 cm. Applications were made with an R&D (Bellspray Inc., Opelousas, LA, USA) CO2 backpack sprayer, using a 1 L plastic bottle, calibrated to deliver 418 L per hectare at 241 kPa (∼15.4 ml per plot). Treatments were applied at 06:00 in early August, 2007. Four hours after treatment, five uprights were randomly collected from each plot and inserted in florists’ water picks, enclosed in a ventilated 40-dram plastic vial, and secured on polystyrene foam trays. Each replicate consisted of a total of 10 vials per treatment (N = 30 vials per treatment). Four S. sulfureana neonates were added to each vial, and vials were placed in the laboratory at ∼25°C. The number of live larvae was recorded after 7 days.

To confirm that the effects of the JA treatment on S. sulfureana larval survival were the result of plant effects rather than any direct toxic effects of JA, an additional experiment was conducted to test the toxicity of JA to S. sulfureana neonates. Sparganothis sulfureana neonates were placed in 30 ml plastic cups (one neonate per cup), containing 10 ml of wheat germ diet. The diet in each cup was sprayed with either 1 mM JA solution with 0.4% acetone or distilled water with 0.4% acetone 4 h prior to placing the caterpillars (N = 50 cups per treatment). The number of live larvae was recorded after 7 days.

Data analysis

The normalized gene expression levels were log-transformed, to satisfy the homogeneity of variance assumption for ANOVA. However, even with this transformation, responses of two genes (BCS and TPS21) to one treatment (systemic response in mechanically wounded plants) had excessively large variances, so were excluded from the analyses. Linear mixed models were fit with the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2011) in R (R Development Core Team, 2012) (with biological replicate as a random effect) to a subset of genes whose expression levels changed over treatments, means separations within a gene were done using the multcomp package (Hothorn et al., 2008).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to visualize overall differences among blends emitted from each treatment (gypsy moth feeding, MeJA, mechanical wounding, and control) using Minitab v. 16 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). PCA was initially performed on the data because individual volatile compounds within blends are not independent (Hare, 2011). We also used multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA; Minitab) to analyze the effects of treatment on volatile emissions. Volatile compounds were grouped into esters, monoterpenes, homoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, or others (only groups containing more than two compounds were considered for MANOVA). A significant MANOVA was followed by ANOVA (Minitab) to determine which compounds within a group were affected by treatment (Scheiner, 2001). Similarly, PCA and ANOVA were used to test the effect of time of day on volatiles emissions from MeJA-treated plants (06:00–10:00, 10:00–14:00, 14:00–18:00, 18:00–22:00, and 22:00–06:00). Volatile emissions data were either ln(x)- or ln(x + 0.5)-transformed prior to analysis to satisfy assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. Differences in the emissions of individual compounds among treatments were analyzed by Tukey post hoc comparisons (α = 0.05).

Sticky trap data were first analyzed by functional group, i.e., herbivores and natural enemies (predators and parasitoids), using MANOVA. MANOVA was initially performed on the data because densities of individual arthropod groups are not independent (Scheiner, 2001). The model included treatment (MeJA versus control), time of year (date), and treatment × date. A significant MANOVA was followed by ANOVA for individual arthropod groups. When needed, data were ln(x) or ln(x + 0.5)-transformed before analysis. Mortality data were arcsine square-root transformed before analysis with ANOVA. A chi-square test was used to determine differences in S. sulfureana mortality rate when fed diets sprayed with JA versus unsprayed diets.

The values of the EAG depolarization amplitude after exposure to the volatile compounds were transformed [ln(x + 0.5)] prior to analysis with two-way ANOVA with sex of insect and type of chemical compound as the two factors. Significant ANOVA results were followed by Tukey test for means comparison.

Results

Gene expression

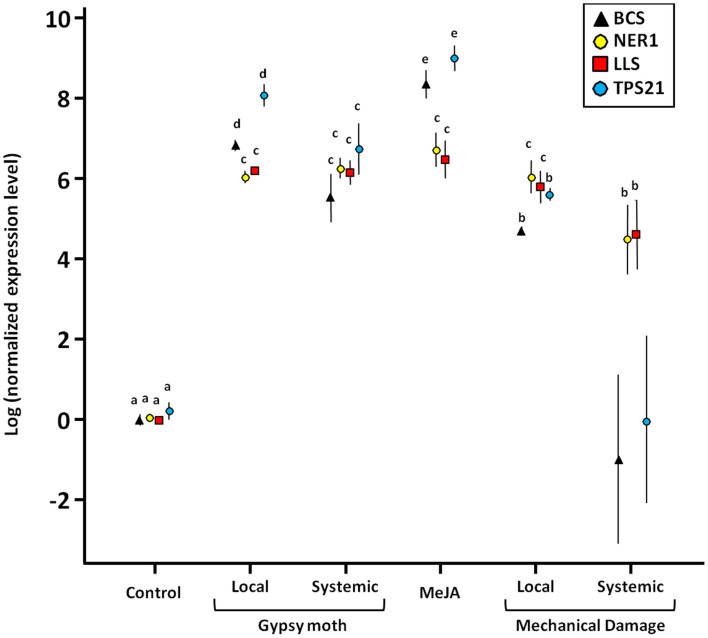

To determine if the various treatments induced expression of key enzymes in the terpenoid biosynthetic pathway, we tested the relative expression levels of eight selected genes – BCS, FDS, LLS, MDS, NER1, PMK, TPS, TPS21 – using real-time PCR. Four of the genes tested responded significantly to gypsy moth larval feeding, MeJA, and mechanical wounding (BCS, LLS, NER1, and TPS21), but to different degrees (Figure 1). The most dramatic changes in expression of BCS and TPS21 were when treated with MeJA. All MeJA-treated plants also had significantly elevated expression of LLS and NER1. For those genes that responded to gypsy moth feeding (BCS, LLS, NER, and TPS21), the changes in gene expression were also evident in the undamaged tissue on the same plant. This was also true in mechanically wounded plants, but only for NER1 and LLS. The undamaged leaves from the mechanically wounded plants had a wide variance in gene expression for BCS and TPS21. Expression of the other four genes tested (FDS, MDS, PMK, TPS) were unchanged for any of the treatments (P > 0.05; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression of terpene genes (BCS, NER1, LLS, and TPS21) in cranberries, Vaccinium macrocarpon, in response to gypsy moth larval feeding, MeJA, and mechanical damage as compared to control plants. Targets: BCS = (-)-β-caryophyllene synthase; NER1 = (3S,6E)-nerolidol synthase; LLS = R-linalool synthase; TPS21 = α-humulene/β-caryophyllene synthase. Local = expression at the site of feeding damage or mechanical damage; Systemic = expression of undamaged leaves on damaged plants. Values are the mean ±1 SE. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (adjusted for multiple comparisons); there are four sets of means separation letters, one for each gene. BCS and TPS21 values for “Mechanical Damage-Systemic” were not included in the statistical analysis due to excessively high variance.

Volatile emissions

Cranberry plants responded to gypsy moth feeding in a density-dependent manner such that volatile emissions were ∼2.5 times greater when plants were damaged by eight caterpillars as compared with four caterpillars (four caterpillars [mean emissions in ng h−1 g−1 fresh tissue ± SE]: 81.9 ± 24.1; eight caterpillars: 199.9 ± 18.4; F = 10.41, df = 1.6, P = 0.018). Eleven out of 22 volatiles were significantly induced by herbivory from cranberry plants compared with undamaged plants (Table 2); with eucalyptol/limonene, linalool, DMNT, indole, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, and germacrene-D emitted in highest quantities.

Table 2.

Volatiles identified in the headspace of cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, plants damaged by eight gypsy moth larvae, sprayed with 1 mM MeJA solution, mechanically damaged with scissors, or left undamaged (control)1.

| Compound | Control2 | Gypsy moth | MeJA | Mechanical wounding | F3 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIPOXYGENASE PATHWAY PRODUCTS | ||||||||||

| (Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate4 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | (18)b | 8.7 ± 1.0 | (4)ab | 39.2 ± 31.0 | (13)ab | 313.5 ± 170.6 | (92)a | 4.88 | 0.019 |

| ISOPRENOID PATHWAY PRODUCTS | ||||||||||

| Monoterpenes | ||||||||||

| α-Pinene | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | 1.5 ± 0.6 | (<1)a | n.d. | b | 8.10 | 0.003 |

| Camphene | 1.5 ± 0.1 | (7)bc | 5.1 ± 0.7 | (3)a | 3.0 ± 0.5 | (1)ab | 0.7 ± 0.5 | (<1)c | 10.87 | 0.001 |

| Sabinene | 0.5 ± 0.5 | (2)b | 4.3 ± 0.8 | (2)a | 3.3 ± 0.5 | (1)ab | 9.9 ± 5.2 | (3)a | 5.56 | 0.013 |

| β-Pinene | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | 1.3 ± 0.4 | (<1)a | n.d. | b | 8.93 | 0.002 |

| Myrcene | n.d. | b | 2.3 ± 0.3 | (1)ab | 1.0 ± 0.6 | (<1)a | 0.3 ± 0.3 | (<1) b | 7.01 | 0.006 |

| Eucalyptol/Limonene5 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | (4)b | 9.2 ± 3.6 | (5)a | 3.4 ± 0.8 | (1)ab | 7.3 ± 3.5 | (2)ab | 5.22 | 0.015 |

| Linalool oxide | n.d. | b | 1.4 ± 0.8 | (1)ab | 1.5 ± 0.3 | (<1)a | n.d. | b | 5.93 | 0.01 |

| Linalool | 3.9 ± 0.4 | (18)b | 23.3 ± 3.6 | (12)a | 42.6 ± 10.3 | (14)a | 3.4 ± 0.8 | (1)b | 35.93 | <0.001 |

| Borneol | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 0.4 ± 0.4 | (<1)a | n.d. | a | 1.00 | 0.426 |

| Homoterpenes | ||||||||||

| α-Copaene | n.d. | b | 0.9 ± 0.5 | (<1)ab | 2.1 ± 0.4 | (1)a | n.d. | b | 11.66 | 0.001 |

| β-Cubebene | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 1.6 ± 1.0 | (1)a | n.d. | a | 2.93 | 0.077 |

| β-Caryophyllene | n.d. | b | 28.0 ± 1.8 | (14)a | 37.3 ± 18.5 | (12)a | n.d. | b | 28.71 | <0.001 |

| α-Humulene | n.d. | b | 15.9 ± 1.1 | (8)a | 20.6 ± 9.6 | (7)a | n.d. | b | 41.67 | <0.001 |

| Germacrene-D | n.d. | b | 8.8 ± 1.0 | (4)a | 10.6 ± 5.1 | (3)a | n.d. | b | 32.26 | <0.001 |

| α-Farnesene | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 1.1 ± 0.7 | (<1)a | n.d. | a | 2.89 | 0.079 |

| δ-Cadinene | n.d. | b | 1.4 ± 0.5 | (1)a | 1.5 ± 0.6 | (<1)a | n.d. | b | 5.55 | 0.013 |

| Sesquiterpenes | ||||||||||

| 4,8-Dimethyl-1,3,7-nonatriene6 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | (32)b | 57.5 ± 7.4 | (29)a | 100.0 ± 31.2 | (32)a | 4.1 ± 0.7 | (1)b | 45.46 | <0.001 |

| SHIKIMIC ACID /PHENYLPROPANOID PATHWAY PRODUCTS | ||||||||||

| Indole | n.d. | b | 15.4 ± 3.0 | (8)a | 17.2 ± 2.9 | (6)a | 0.3 ± 0.3 | (<1)b | 87.98 | <0.001 |

| Methyl salicylate | 2.8 ± 0.2 | (13)ab | 3.9 ± 0.2 | (2)a | 2.7 ± 0.7 | (1)ab | 1.8 ± 0.4 | (1)b | 3.88 | 0.038 |

| Phenylethyl ester | n.d. | b | 7.4 ± 0.9 | (4)a | 6.7 ± 1.5 | (2)a | n.d. | b | 160.23 | <0.001 |

| Benzoic acid, ethyl ester | 1.4 ± 0.8 | (6)a | 6.3 ± 5.2 | (3)a | 9.4 ± 2.7 | (3)a | 0.8 ± 0.5 | (<1)a | 2.66 | 0.095 |

| Total | 21.5 ± 1.3 | b | 199.9 ± 18.4 | a | 307.9 ± 71.7 | a | 342.3 ± 180.6 | ab | 6.29 | 0.008 |

1N = 4.

2Mean ng n-octane units h−1 g−1 of fresh tissue (±SE). In parenthesis are percent values based on total amounts. n.d. = not detected (zero values were assigned to non-detectable values for statistical analysis).

3df = 3.12

4For each compound, different letters indicate significant differences between the samples.

5Peaks of these volatile compounds co-eluted in the GC.

6This compound was misidentified as myrcenone (based on spectral library match) in Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2011).

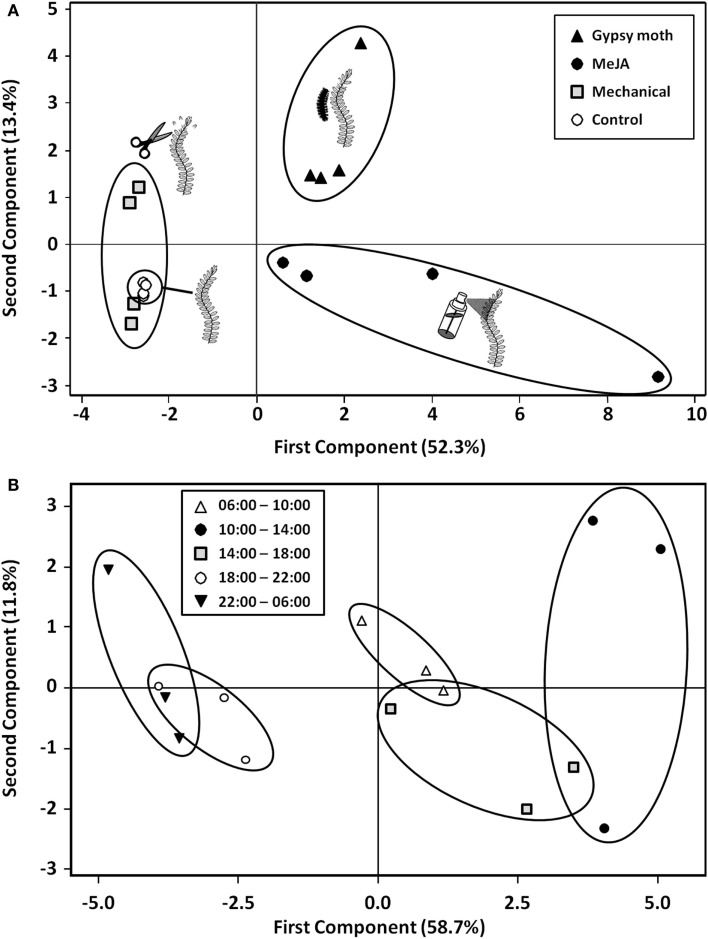

Total emissions of volatiles were 9 and 14-fold higher in gypsy moth-damaged (eight caterpillars) and MeJA-treated plants than in control plants, respectively; whereas emissions from mechanically wounded plants were variable and not significantly different from control plants (Table 2). The PCA resulted in a model with the first two PC components explaining 65.7% of the total variation in volatile blends. The score plot of PC1 versus PC2 shows no overlap among volatile blends of gypsy moth, MeJA, and control treatments, while the mechanically wounded and control treatments overlapped (Figure 2A). The first PC component explained 52.3% of the variation in volatile blend and separated the gypsy moth and MeJA treatments from the mechanically wounded and control treatments; while the second PC component explained 13.4% of the variation in the data and separated the gypsy moth from MeJA treatments (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Score plot of principal component analysis (PCA) for (A) the effects of gypsy moth larval feeding, MeJA, and mechanical damage as compared to control plants on the volatile profiles of cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) leaves, and (B) the effects of time of day on volatile emissions from MeJA-treated plants. Percent variation explained by each principal component is indicated in parenthesis.

Two major biosynthetic pathways in the regulation of plant volatiles were influenced by herbivory and MeJA treatments in cranberries; these included the isoprenoid pathway, that resulted in increased emissions of monoterpenes (MANOVA: Wilks’ λ < 0.001; F = 4.98; P = 0.003), sesquiterpenes (Wilks’ λ < 0.001; F = 19.77; P < 0.001), and homoterpenes, and the shikimic acid/phenylpropanoid pathway (Wilks’ λ = 0.006; F = 11.94; P < 0.001). In particular, emission of linalool, DMNT, phenylethyl ester, indole, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, germacrene-D, and γ-cadinene were higher in the gypsy moth and MeJA treatments compared with the other treatments (Table 2). Only (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate emissions were greater in the mechanically wounded plants compared with the control plants (Table 2).

The score plot shows no overlap between volatiles emitted from MeJA-treated cranberry plants at 10:00–14:00 versus those emitted at 06:00–10:00, 18:00–22:00, and 22:00–06:00 (Figure 2B). Total volatile emissions from MeJA-treated cranberries peaked between 10:00 and 14:00 and were lowest between 18:00 and 06:00 (Table 3). Emissions of linalool, DMNT, methyl salicylate, phenylethyl ester, indole, α-copaene, β-cubebene, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, germacrene-D, and γ-cadinene peaked between 10:00 and 14:00. Only a few compounds (e.g., linalool, DMNT, indole, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, and germacrene-D) were emitted in detectable amounts at dusk (18:00–22:00) and during the scotophase (in the dark) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Time course of volatile emissions from cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, plants sprayed with 1 mM MeJA solution1.

| Compound | 06:00–10:002 | 10:00–14:00 | 14:00–18:00 | 18:00–22:00 | 22:00–06:00 | F3 | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIPOXYGENASE PATHWAY PRODUCTS | ||||||||||||

| (Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate4 | 10.3 ± 0.9 | ab | 13.1 ± 0.7 | a | 33.9 ± 24.8 | a | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | 31.41 | <0.001 |

| ISOPRENOID PATHWAY PRODUCTS | ||||||||||||

| Monoterpenes | ||||||||||||

| α-Pinene | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | |||||

| Camphene | 7.8 ± 1.1 | a | 12.8 ± 2.3 | a | 11.0 ± 1.3 | a | n.d. | b | 0.8 ± 0.8 | b | 28.81 | <0.001 |

| Sabinene | 2.0 ± 2.2 | a | 5.2 ± 2.6 | a | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 2.14 | 0.151 |

| β-Pinene | n.d. | b | 4.8 ± 2.4 | a | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | 3.98 | 0.035 |

| Myrcene | n.d. | a | 2.7 ± 2.7 | a | 2.6 ± 2.6 | a | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 0.75 | 0.58 |

| Eucalyptol/Limonene5 | 9.3 ± 2.9 | ab | 17.0 ± 2.6 | a | 15.0 ± 2.8 | a | 1.6 ± 1.6 | bc | 0.7 ± 0.7 | c | 9.69 | 0.002 |

| Linalool oxide | n.d. | a | 2.5 ± 2.5 | a | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 1.00 | 0.452 |

| Linalool | 85.7 ± 20.3 | a | 135.8 ± 23.3 | a | 52.8 ± 14.4 | ab | 9.4 ± 0.9 | bc | 2.5 ± 1.3 | c | 19.85 | <0.001 |

| Borneol | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | |||||

| Sesquiterpenes | ||||||||||||

| α-Copaene | 5.2 ± 2.8 | ab | 13.2 ± 1.9 | a | 10.6 ± 0.7 | ab | 2.0 ± 2.0 | b | 0.9 ± 0.9 | b | 3.75 | 0.041 |

| β-Cubebene | 2.3 ± 2.3 | ab | 19.0 ± 3.9 | a | 9.8 ± 4.9 | ab | n.d. | b | 1.4 ± 1.4 | b | 3.84 | 0.038 |

| β-Caryophyllene | 123.8 ± 31.0 | ab | 365.5 ± 104.3 | a | 264.2 ± 34.3 | a | 75.1 ± 20.4 | ab | 43.7 ± 16.6 | b | 7.63 | 0.004 |

| α-Humulene | 66.4 ± 16.6.6 | ab | 193.7 ± 55.6 | a | 152.2 ± 21.5 | a | 42.5 ± 10.9 | ab | 25.9 ± 10.2 | b | 6.68 | 0.007 |

| Germacrene-D | 36.0 ± 10.5.5 | ab | 104.9 ± 48.1 | a | 74.1 ± 14.3 | ab | 18.5 ± 6.7 | ab | 9.3 ± 4.7 | b | 3.87 | 0.038 |

| α-Farnesene | n.d. | a | 14.1 ± 7.2 | a | 8.6 ± 4.3 | a | n.d. | a | n.d. | a | 3.00 | 0.072 |

| δ-Cadinene | n.d. | b | 17.7 ± 6.8 | a | 10.0 ± 5.1 | a | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | 9.30 | 0.002 |

| Homoterpenes | ||||||||||||

| 4,8-Dimethyl-1,3,7-nonatriene | 223.1 ± 75.2 | ab | 635.8 ± 252.4 | a | 450.3 ± 128.2 | ab | 80.2 ± 34.4 | bc | 24.5 ± 10.5 | c | 11.90 | 0.001 |

| SHIKIMIC ACID/PHENYLPROPANOID PATHWAY PRODUCTS | ||||||||||||

| Indole | 39.8 ± 4.8 | ab | 56.8 ± 11.2 | a | 41.1 ± 12.2 | ab | 20.0 ± 3.2 | b | 12.9 ± 2.8 | b | 8.72 | 0.003 |

| Methyl salicylate | 9.8 ± 1.9 | a | 11.3 ± 2.8 | a | 4.5 ± 2.3 | ab | n.d. | b | 1.2 ± 1.2 | ab | 6.80 | 0.007 |

| Phenylethyl ester | 13.3 ± 6.8 | ab | 53.2 ± 18.3 | a | 15.4 ± 15.4 | ab | n.d. | b | n.d. | b | 4.49 | 0.025 |

1N = 3. MeJA was applied 16 h before volatile collections.

2Mean ng n-octane units h−1 g−1 of fresh tissue (±SE). n.d. = not detected (zero values were assigned to non-detectable values for statistical analysis).

3df = 4.10.

4For each compound, different letters indicate significant differences between the samples.

5Peaks of these volatile compounds co-eluted in the GC.

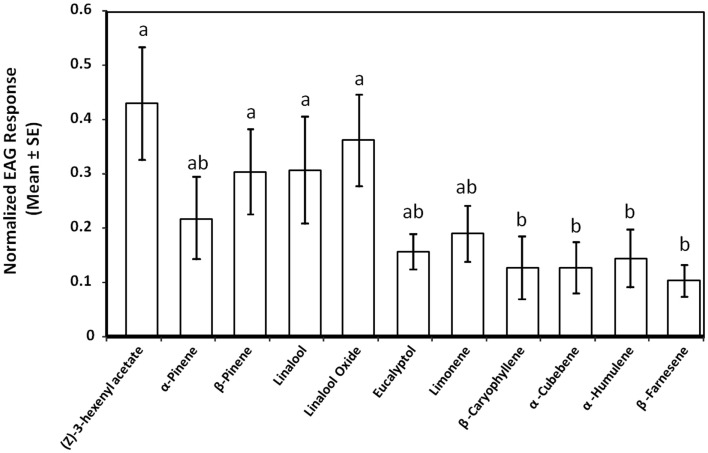

Electroantennography

We used EAG to determine the antennal activity of a polyphagous herbivore, S. sulfureana, to various cranberry volatiles. The magnitude of the EAG response was significantly different among the tested chemical compounds (F = 2.29, df = 10,129, P = 0.017). The EAG responses between males and females were, however, not different (F = 1.28, df = 1,129, P = 0.261), nor the interaction between chemical compound and sex of insect (F = 0.99, df = 10,129, P = 0.458). Antennal responses were greater to (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, β-pinene, linalool, and linalool oxide compared with β-caryophyllene, α-cubebene, α-humulene, and β-farnesene (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Electroantennogram (EAG) responses of Sparganothis fruitworm, Sparganothis sulfureana, to various cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, leaf volatiles. For analysis, control depolarizations (hexane) were subtracted from the test stimuli values. Different letters indicate significant differences among means (P ≤ 0.05). Results of male and female S. sulfureana responses were combined in the graph (N = 13–17).

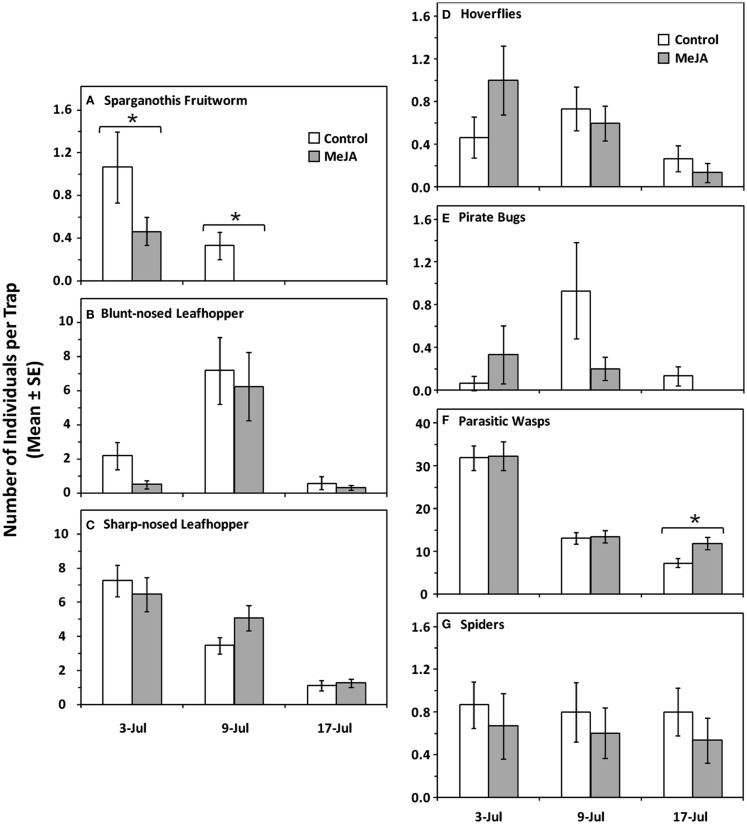

Ecological level

Three herbivores were most abundant on sticky traps; these were: the Sparganothis fruitworm, S. sulfureana, the sharp-nosed leafhopper, Scaphytopius magdalensis Provancher (Hem., Cicadellidae), and the blunt-nosed leafhopper, Limotettix vaccinii (Van Duzee) (Hem., Cicadellidae). The most abundant groups of natural enemies on traps were hoverflies [mainly Toxomerus marginatus (Say)], minute pirate bugs (Orius spp.), spiders, and parasitic wasps.

MeJA treatment (MANOVA: Wilks’ λ = 0.86, F = 3.36, df = 4.81, P = 0.014), date (Wilks’ λ = 0.29, F = 16.85, df = 8.162, P < 0.001), but not treatment × date interaction (Wilks’ λ = 0.87, F = 1.39, df = 8.162, P = 0.201) had a significant negative effect on herbivore abundance on sticky traps. When analyzed in more detail, MeJA had an effect on S. sulfureana moths (treatment: F = 6.10, df = 1.84, P = 0.016; date: F = 13.66, df = 2.84, P < 0.001; treatment × date interaction: F = 1.90, df = 2.84; P = 0.156) (Figure 4A), but not on the leafhoppers L. vaccinii (treatment: F = 2.10, df = 1.84, P = 0.151; date: F = 30.83, df = 2.84, P < 0.001; treatment × date interaction: F = 1.06, df = 2.84; P = 0.352) (Figure 4B), or S. magdalensis (treatment: F = 1.51, df = 1.84, P = 0.223; date: F = 29.43, df = 2.84, P < 0.001; treatment × date interaction: F = 0.45, df = 2.84; P = 0.638) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Mean numbers of arthropods per sticky trap placed near cranberry plants treated with exogenous MeJA and untreated plants (control). Herbivores: (A) Sparganothis fruitworm, Sparganothis sulfureana (Lep., Tortricidae), (B) blunt-nosed leafhoppers, Limotettix vaccinii (Hem., Cicadellidae), (C) sharp-nosed leafhopper, Scaphytopius magdalensis (Hem., Cicadellidae). Natural enemies: (D) hoverflies (mainly Toxomerus marginatus) (Dip., Syrphidae), (E) minute pirate bugs (Orius spp.) (Hem., Anthocoridae), (F) parasitic wasps (Hymenoptera), and (G) spiders (Araneae). Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between MeJA and control treatments (P ≤ 0.05); all other comparisons were non-significant (P > 0.05).

Abundance of natural enemies on sticky traps were positively affected by MeJA treatment (MANOVA: Wilks’ λ = 0.68, F = 9.122, df = 4.81, P < 0.001), date (Wilks’ λ = 0.28, F = 17.57, df = 8.162, P < 0.001), and treatment × date interaction (Wilks’ λ = 0.47, F = 9.10, df = 8.162, P < 0.001). When analyzed in more detail, MeJA had a positive effect on parasitic wasps (treatment: F = 36.43, df = 1.84, P < 0.001; date: F = 91.56, df = 2.84, P < 0.001; treatment × date interaction: F = 36.48, df = 2.84; P < 0.001) (Figure 4F), but not on the hoverfly T. marginatus (treatment: F = 0.31, df = 1.84, P = 0.582; date: F = 4.35, df = 2.84, P = 0.016; treatment × date interaction: F = 1.91, df = 2.84; P = 0.155) (Figure 4D), minute pirate bugs (treatment: F = 1.19, df = 1.84, P = 0.278; date: F = 2.67, df = 2.84, P = 0.075; treatment × date interaction: F = 2.52, df = 2.84; P = 0.087) (Figure 4E), or spiders (treatment: F = 1.21, df = 1.84, P = 0.275; date: F = 0.08, df = 2.84, P = 0.919; treatment × date interaction: F = 0.01, df = 2.84; P = 0.988) (Figure 4G).

Sparganothis sulfureana larval mortality was significantly higher when fed foliage from JA-treated cranberry plants as compared with those fed foliage from untreated plants [mean (± SE) percent mortality = JA: 42.5% (±13.5); control = 0% (±0); F = 33.37, df = 1.6, P = 0.001]. Moreover, the negative effects of JA on larval mortality were attributable to the activation of plant defenses by JA and not to direct toxicity because mortality rates were similar on JA-treated (4%) and untreated diets (8%) (χ2 = 0.67; df = 1; P = 0.414).

Discussion

Jasmonates such as jasmonic acid and MeJA can serve as an important tool in insect pest management for plant protection against herbivorous pests (Thaler, 1999a; Rohwer and Erwin, 2008; Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2012). Before this can be achieved, however, studies are needed that link the activation of defensive genes by these hormones in plants, the plant’s biochemical changes, and the response of both antagonistic and mutualistic organisms to jasmonate-induced plants. In this study, we showed that: (1) herbivory by gypsy moth caterpillars, jasmonate treatment, and mechanical wounding induce, albeit differently, the expression of genes from two different pathways in the biosynthesis of terpene compounds, i.e., the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway that produces sesquiterpenes and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway that leads to monoterpene production (Lichtenthaler et al., 1997; Paré and Tumlinson, 1999; Bartram et al., 2006; Dudareva et al., 2013); (2) herbivore feeding and jasmonate treatment, but not mechanical wounding, induced emissions of monoterpene, homoterpene, and sesquiterpene volatiles; however, blends were distinct from one another; and, (3) jasmonate treatment reduced preference and performance of the herbivore S. sulfureana to cranberry plants, and increased colonization by parasitic wasps. Furthermore, S. sulfureana antennae were highly sensitive to inducible monoterpenes, in particular linalool, which might explain the repellence effects of jasmonate-induced plants.

At the molecular level, expression of genes from two isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways – the MVA and MEP pathways – were activated by gypsy moth feeding, MeJA, and mechanical wounding. Of the eight genes targeted in this study – BCS, FDS, LLS, MDS, NER1, PMK, TPS, TPS21, four responded significantly to gypsy moth larval feeding, MeJA, and mechanical wounding (BCS, LLS, NER1, and TPS21), but to different degrees. Expression of the other four genes (FDS, MDS, PMK, and TPS) did not change. MDS, PMK, and FDS are higher up in the terpenoid pathway (Terpenoid Backbone Biosynthesis pathway; KEGG map00900), so the whole pathway is not being induced by larval feeding, MeJA, or mechanical wounding but rather the genes involved in the synthesis of specific terpenes. These data thus indicate that cranberry leaves use pre-formed intermediates to rapidly make specific terpenes. The most dramatic changes in expression of BCS and TPS21 were when treated with MeJA; these genes are in the MVA pathway and the enzymes encoded catalyze the production of β-caryophyllene and α-humulene, respectively. Gypsy moth-damaged and MeJA-treated plants also had elevated expression of LLS and NER1 [LLS is in the MEP pathway and the encoded enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of linalool; NER1 is in the homoterpene biosynthesis pathway and the encoded enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of nerolidol-derived DMNT (Boland et al., 1998)]. Interestingly, for those genes that responded to gypsy moth feeding (BCS, LLS, NER1, and TPS21), the changes in gene expression were also evident in the undamaged tissue on the same plant, indicating a systemic response in gene expression. This was also true in mechanically wounded plants, but only for NER1 and LLS; thus, genes from the MVA pathway do not appear to be expressed systemically by mechanical wounding.

At the biochemical level, volatiles from the MVA pathway (e.g., β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, and germacrene-D) were strongly induced by gypsy moth feeding but not by mechanical wounding in cranberries. Similarly, volatiles from the MEP pathway (e.g., camphene, eucalyptol/limonene, and linalool) were strongly induced by gypsy moth feeding but not or only weakly induced by mechanical wounding. These data suggest that insect-derived elicitors (see Alborn et al., 1997) are required for the induction of terpene emissions in cranberries. In a previous study, Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2011) found differences in the volatile response to gypsy moth feeding among five cranberry varieties, indicating genotypic variation in the volatile response of cranberries to herbivore feeding. Contrary, they reported similar induction of volatiles by MeJA among these varieties (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011). In this study, we also showed that MeJA induces a blend of volatiles in cranberries that was different from herbivore feeding. Other studies have reported a high degree of resemblance, but also some qualitative and quantitative differences, between jasmonate and herbivore-induced volatile profiles (e.g., Dicke et al., 1999; Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2001, 2006; Gols et al., 2003). Altogether, previous data (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2011) and the present data indicate that signals (i.e., hormones) other than jasmonates might be involved in the emission of HIPVs in cranberries. For example, ethylene was found to interact with JA and the insect-derived elicitor volicitin in the induction of volatile emissions from maize seedlings (Schmelz et al., 2003).

Herbivory and MeJA also induced indole and phenylethyl ester emissions, both products of the shikimic acid pathway (Paré and Tumlinson, 1999), indicating that induced volatiles in cranberries originate mainly from the isoprenoid and shikimic acid pathways. On the other hand, mechanical wounding increased emissions of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, a product of the lipoxygenase pathway and that is often emitted rapidly in plants as a result of wounding (Paré and Tumlinson, 1999; Chehab et al., 2008).

At the organismal level, jasmonates were involved in the activation of both direct (i.e., plant chemicals that deter or kill the herbivore) and indirect (i.e., chemicals such as HIPVs that attract the herbivores’ natural enemies) resistance in cranberries. Host-plant preference and performance were correlated for the polyphagous herbivore S. sulfureana: adults were less attracted to, and larval survival was reduced on, jasmonate-induced plants. Table 4 summarizes studies on the effects of jasmonates on herbivorous arthropod performance and preference – we limit this list to studies that used methodologies similar to ours, i.e., jasmonates (JA or MeJA) were sprayed exogenously on plants; thus, investigated only local responses. Out of 37 herbivore-plant interactions reported in these studies, 31 (84%) showed a negative effect of jasmonates on herbivores, while positive effects accounted for only 8%. Negative effects on the herbivores included lower abundance, performance, colonization, and oviposition on jasmonate-induced plants (Table 4) – likely resulting in increased foraging time and reduced overall fitness; while positive effects included greater abundance, attraction, and oviposition (Table 4). Interestingly, the western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis Pergande, performs poorly on tomato (Thaler et al., 2001) and Chinese cabbage (Abe et al., 2009) induced by JA, whereas it has higher performance on JA-induced cotton (Omer et al., 2001). Likewise, the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L., was more attracted for oviposition to JA-treated compared with untreated common cabbage, while it was less attracted to JA-treated than untreated Chinese cabbage (Lu et al., 2004). Thus, the outcome of these interactions can be host-plant dependent.

Table 4.

Effects of jasmonic acid (JA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) sprayed exogenously to plants on herbivorous arthropods1.

| Arthropod Species | Common Name | Feeding Guild | Elicitor | Concentration (mM) | Ecological Effects | Overall Effect | Plant | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spodoptera exigua | Beet armyworm | Chewer | JA | 0.5 | Lower growth rate/feeding | Negative | Tomato | Laboratory | Thaler et al. (1996) |

| Manduca sexta | Tobacco hornworm | Chewer | JA | 1 | Lower growth rate | Negative | Tomato | Greenhouse | Cipollini and Redman (1999) |

| Unknown | Unknown | Chewer | JA | 0.5, 1.5 | Lower feeding damage | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler (1999c) |

| Daktulosphaira vitifoliae | Grape phylloxera | Phloem feeder (roots) | JA | 1 | Lower performance | Negative | Grape | Greenhouse | Omer et al. (2000) |

| Tetranychus pacificus | Pacific spider mite | Cell-content feeder | JA | 1 | Lower performance | Negative | Grape | Greenhouse | Omer et al. (2000) |

| Spodoptera exigua | Beet armyworm | Chewer | JA | 0.5, 1.5 | Lower performance | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler et al. (2001) |

| Macrosiphum euphorbiae | Potato aphid | Phloem feeder | JA | 0.5, 1.5 | Lower abundance | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler et al. (2001) |

| Myzus persicae | Green peach aphid | Phloem feeder | JA | 0.5, 1.5 | Lower abundance | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler et al. (2001) |

| Frankliniella occidentalis | Western flower thrips | Cell-content feeder | JA | 0.5, 1.5 | Lower abundance | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler et al. (2001) |

| Epitrix hirtipennis | Flea beetle | Chewer | JA | 0.5, 1.5 | Lower abundance | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler et al. (2001) |

| Aphis gossypii | Cotton aphid | Phloem feeder | JA | 1 | Lower abundance | Negative | Cotton | Greenhouse/laboratory | Omer et al. (2001) |

| Tetranychus urticae | Two-spotted spider mite | Cell-content feeder | JA | 1 | Lower abundance | Negative | Cotton | Greenhouse/laboratory | Omer et al. (2001) |

| Frankliniella occidentalis | Western flower thrips | Cell-content feeder | JA | 1 | Higher abundance | Positive | Cotton | Greenhouse/laboratory | Omer et al. (2001) |

| Aphis gossypii | Aphid nymphs | Phloem feeder | JA | 1 | Lower performance | Negative | Cotton | Greenhouse/laboratory | Omer et al. (2001) |

| Tetranychus urticae | Two-spotted spider mite | Cell-content feeder | JA | 0.1–1 | Lower abundance | Negative | Lima bean | Laboratory | Gols et al. (2003) |

| Unknown | Unknown | Chewer | JA | 1 | Lower feeding damage | Negative | Lima bean | Field | Heil (2004) |

| Plutella xylostella | Diamonback moth | Nectar feeder | JA | 0.01–1 | Lower oviposition | Negative | Chinese cabbage | Field/laboratory | Lu et al. (2004) |

| Plutella xylostella | Diamonback moth | Nectar feeder | JA | 0.01–1 | Higher oviposition | Positive | Common cabbage | Field/laboratory | Lu et al. (2004) |

| Macrosiphum euphorbiae | Potato aphid | Phloem feeder | JA | 1.5 | Lower performance | Negative | Tomato | Greenhouse | Cooper and Goggin (2005) |

| Ips typographus | Spruce bark beetle | Chewer | MeJA | 100 | Lower colonization/higher resistance | Negative | Norway spruce | Field | Erbilgin et al. (2006) |

| Agrilus planipennis | Emerald ash borer | Chewer | MeJA | 1.4 | Higher attraction | Positive | Manchurian ash | Laboratory | Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2006) |

| Myzus persicae | Green peach aphid | Phloem feeder | MeJA | 1, 5, 10 | Lower population growth | Negative | Tomato | Greenhouse | Boughton et al. (2006) |

| Pieris rapae | Small cabbage white | Nectar feeder | JA | 0.1 | Lower oviposition | Negative | Brussels sprouts | Greenhouse | Bruinsma et al. (2007) |

| Pieris brassicae | Cabbage white | Nectar feeder | JA | 0.1 | Lower oviposition | Negative | Brussels sprouts | Greenhouse | Bruinsma et al. (2007) |

| Pieris rapae | Small cabbage white | Nectar feeder | JA | 0.5 | Lower oviposition | Negative | Black mustard | Greenhouse | Bruinsma et al. (2008) |

| Nilaparvata lugens | Brown planthopper | Phloem feeder | JA | 2.5, 5 | Increase resistance | Negative | Rice | Greenhouse | Senthil-Nathan et al. (2009) |

| Frankliniella occidentalis | Western flower thrips | Cell-content feeder | JA | 0.05 | Increase resistance | Negative | Chinese cabbage | Greenhouse | Abe et al. (2009) |

| Tetranychus urticae | Two-spotted spider mite | Cell-content feeder | MeJA | 0.1 | Increase dispersal/resistance | Negative | Impatiens, Pansy, Tomato | Greenhouse | Rohwer and Erwin (2010) |

| Tetranychus urticae | Two-spotted spider mite | Cell-content feeder | MeJA | N/A2 | Increase resistance | Negative | Apple, strawberry | Greenhouse | Warabieda and Olszak (2010) |

| Dendrolimus superans | Larch caterpillar moth | Chewer | JA | 0.01–1 | Lower oviposition | Negative | Larch | Laboratory | Meng et al. (2011) |

| Lymantria dispar | Gypsy moth | Chewer | JA | 1 | Increase resistance | Negative | Cranberry | Laboratory | Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2011) |

| Helicoverpa armigera | Cotton bollworm | Nectar feeder | MeJA | 1.5 | No effect on oviposition | None | Tomato | Greenhouse | Tan et al. (2012) |

| Gynandrobrotica guerreroensis | – | Chewer | JA | 0.001–1 | Repellency (females) | Negative | Lima bean | Laboratory | Ballhorn et al. (2013) |

| Cerotoma ruficornis | – | Chewer | JA | 0.001–1 | Repellency (females) | Negative | Lima bean | Laboratory | Ballhorn et al. (2013) |

| Sparganothis sulfureana | Sparganothis fruitworm | Nectar feeder | MeJA, JA | 1 | Lower attraction/performance | Negative | Cranberry | Field | This study |

| Scaphytopius magdalensis | Sharp-nosed leafhopper | Phloem feeder | MeJA | 1 | No effect on abundance | None | Cranberry | Field | This study |

| Limotettix vaccinii | Blunt-nosed leafhopper | Phloem feeder | MeJA | 1 | No effet on abundance | None | Cranberry | Field | This study |

1Listed in chronological order.

2Not indicated

The mechanism of the repellent effects of MeJA on adult S. sulfureana remains unknown – it is not known which compound(s) is responsible for these effects. Both male and female S. sulfureana antennae responded strongly to four cranberry volatiles [(Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, β-pinene, linalool, and linalool oxide]; however, only linalool was emitted in detectable amounts from MeJA-treated cranberry plants during dusk and nighttime (Table 3), when moths are expected to be most active. The more attractive cranberry plants to S. sulfureana (controls) emitted low quantities of linalool constitutively; whereas less attractive plants (MeJA-treated) emitted this compound in high amounts (Table 2). This compound has important behavioral effects on other moth species both as an attractant (e.g., Suckling et al., 1996; Raguso et al., 2003) and a repellent (e.g., Kessler and Baldwin, 2001; McCallum et al., 2011), and possibly also on S. sulfureana. Also, the herbivore Spodoptera frugiperda Smith showed an increment in the antennal response (EAG) to linalool at higher doses (Malo et al., 2004). In our study we could not discard the possibility that jasmonates themselves caused the effect. It was also difficult to determine the gender of the moths on sticky cards because of their poor condition, i.e., moths were either too dry or covered with adhesive. Further studies are needed on the dose-dependent effects of linalool and other induced volatile compounds on S. sulfureana foraging behavior, and to determine if gender differences exist in S. sulfureana’s response to jasmonate-induced plants and, in particular, the effects of induced volatiles on oviposition.

In contrast to herbivores, the majority (11 out of 18 or 61%) of natural enemy-plant interactions involving jasmonate-induce plants were positive (Table 5). All these interactions involved greater attraction to induced plants likely through increases in volatile emissions. Only 1 out of 18 case studies (6%) reported a negative effect of jasmonates on natural enemies (Table 5). Thaler (2002) reported reduced number of hoverfly eggs laid on induced plants due to a decrease in aphid (prey) abundance. Interestingly, Thaler (2002) found no effect on adult Hyposoter exiguae Viereck caught on sticky traps placed beneath the canopy of control and JA-induce tomato plants. However, a previous study (Thaler, 1999b) showed higher parasitism of Spodoptera exigua Hübner larvae by H. exiguae on JA-induced induced tomato plants, indicating a possible discrepancy between adult attraction and parasitism rate. In the present study, higher numbers of parasitic wasps were caught on sticky traps near MeJA-treated plants than on untreated plants. This attraction coincided with the time of S. sulfureana egg laying and larval development; whether this effect translates to greater parasitism of S. sulfureana eggs or larvae (or other herbivore pest) requires further investigation. Additional studies are also needed to address the identity and function of these parasitic wasps.

Table 5.

Effects of jasmonic acid (JA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) sprayed exogenously to plants on natural enemy behavior through induction of volatiles1.

| Arthropod species | Common name | Feeding guild | Elicitor | Concentration (mM) | Ecological effects | Overall effect | Plant | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyposoter exigua | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 0.5 | Higher parasitism | Positive | Tomato | Field | Thaler (1999b) |

| Phytoseiulus persimilis | Predatory mite | Predator | JA | 1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Lima bean | Laboratory | Dicke et al. (1999) |

| Cotesia rubecula | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Arabidopsis thaliana | Laboratory | van Poecke and Dicke (2002) |

| Unknown | Hoverfly | Predator | JA | 0.5 | Lower abundance | Negative | Tomato | Field | Thaler (2002) |

| Hyposoter exigua | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 0.5 | No effect on adult abundance | None | Tomato | Field | Thaler (2002) |

| Hippodamia convergens | Convergent lady beetle | Predator | JA | 0.5 | No effect | None | Tomato | Field | Thaler (2002) |

| Aphelinid spp. | Aphid parasitoid | Parasitoid | JA | 0.5 | No effect | None | Tomato | Field | Thaler (2002) |

| Phytoseiulus persimilis | Predatory mite | Predator | JA | 0.1–1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Lima bean | Laboratory | Gols et al. (2003) |

| Cotesia kariyai | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Corn | Laboratory | Ozawa et al. (2004) |

| Cotesia glomerata | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 0.5 | Higher attraction | Positive | Black mustard | Greenhouse | Bruinsma et al. (2008) |

| Eristalis tenax | Syrphid fly | Predator | JA | 0.5 | No effect on adults | None | Black mustard | Field | Bruinsma et al. (2008) |

| Cotesia glomerata | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Brussels sprouts | Laboratory | Bruinsma et al. (2009) |

| Cotesia rubecula | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 1 | Higher attraction | positive | Brussels sprouts | Laboratory | Bruinsma et al. (2009) |

| Diadegma semiclausum | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Brussels sprouts | Laboratory | Bruinsma et al. (2009) |

| Anastatus japonicas | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | JA | 0.01–1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Larch | Laboratory | Meng et al. (2011) |

| unknown (complex) | Parasitic wasp | Parasitoid | MeJA | 1 | Higher attraction | Positive | Cranberry | Field | This study |

| Toxomerus marginatus | Hoverfly | Predator | MeJA | 1 | No effect on adults | None | Cranberry | Field | This study |

| Orius spp. | Pirate bug | Predator | MeJA | 1 | No effect | None | Cranberry | Field | This study |

1Listed in chronological order.

In summary, this study demonstrates the potential of jasmonates as natural plant protectants against herbivorous pests in cranberries. It also summarizes the overall effects of these phytohormones on herbivorous arthropods and their natural enemies (Tables 4 and 5). These studies show that jasmonates provide protection against herbivores from multiple feeding guilds (chewers, phloem feeders, and cell-content feeders) and increase natural enemy attraction in various agro-ecosystems. However, jasmonate-induced responses can be costly in the absence of herbivores (Baldwin, 1998; Cipollini et al., 2003; but see Thaler, 1999c), or could lead to ecological costs due to trade-offs between resistance to herbivores and pathogens (Felton and Korth, 2000). Further studies are needed to measure these costs in cranberries. Other remaining concerns include: the cost of spraying cranberry fields with MeJA, the length of the effect, and the possibility of inducing all plants and producing a no-choice situation.

In addition, this study integrates multiple levels of biological organization from gene expression to biochemical activation to ecological consequences. Such studies are needed for a better understanding of plant-arthropod interactions (Zheng and Dicke, 2008); yet, we are not aware of any similar studies that investigated the effects of jasmonates (e.g., JA or MeJA) on plants and arthropods at all of these three levels of biological organization (molecular, biochemical, and organismal) in a single study (but see Birkett et al., 2000). Our data show general agreement across all three biological levels of organization: key genes from the terpene pathway were highly expressed in MeJA-treated cranberry plants and terpene volatiles were induced by MeJA, which in turn led to repellency of an herbivore and attraction of certain natural enemies. There were, however, some discrepancies: mechanical wounding induced the local expression of four terpene genes – BCS, LLS, NER1, and TPS21 – that encode the enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of β-caryophyllene, linalool, DMNT, and α-humulene, respectively; however, none of these volatiles were emitted in quantities different from unwounded plants. Therefore, we highlight the need of multiple approaches for a more complete assessment on the effects of various environmental stresses that activate the jasmonate signaling – such as herbivory – on plant-insect interactions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the topic editors for their invitation to submit this contribution and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also to Robert Holdcraft, Vera Kyryczenko-Roth, Kristia Adams, Jennifer Frake, and Elizabeth Bender for laboratory and field assistance. Our special thanks to Dr. Thomas Hartman (Rutgers University, Mass Spectrometry Support Facility) and Dr. Hans Alborn (USDA-ARS, Center for Medical, Agricultural, and Veterinary Entomology) for their assistance in volatile identification, and to Matthew Kramer (USDA-ARS, Biometrical Consulting Service) for the statistical analyses of gene expression and for generating the graph presented in Figure 1. This work was supported by the USDA NIFA Special Grant “Blueberry and Cranberry Disease, Breeding and Insect Management” to Cesar R. Rodriguez-Saona and James Polashock, and by hatch funds to Cesar R. Rodriguez-Saona.

References

- Abe H., Shimoda T., Ohnishi J., Kugimiya S., Narusaka M., Seo S., et al. (2009). Jasmonate-dependent plant defense restricts thrips performance and preference. BMC Plant Biol. 9:97. 10.1186/1471-2229-9-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A. A. (1998). Induced responses to herbivory and increased plant performance. Science 279, 1201–1202 10.1126/science.279.5354.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A. A. (2000). Benefits and costs of induced plant defense for Lepidium virginicum (Brassicaceae). Ecology 81, 1804–1813 10.2307/177272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alborn H. T., Turlings T. C. J., Jones T. H., Stenhagen G., Loughrin J. H., Tumlinson J. H. (1997). An elicitor of plant volatiles from beet armyworm oral secretion. Science 276, 945–949 10.1126/science.276.5314.945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura G.-I., Kost C., Boland W. (2005). Herbivore-induced, indirect plant defences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1734, 91–111 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill A. L., Sylvia M. M. (1998). Cranberry Insects of the Northeast. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Extension [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin I. T. (1998). Jasmonate-induced responses are costly but benefit plants under attack in native populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 8113–8118 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballhorn D. J., Kautz S., Heil M. (2013). Distance and sex determine host plant choice by herbivorous beetles. PLoS ONE 8:e55602. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram S., Jux A., Gleixner G., Boland W. (2006). Dynamic pathway allocation in early terpenoid biosynthesis of stress-induced lima bean leaves. Phytochemistry 67, 1661–1672 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Maechler M., Bolker B. (2011). lme4: Linear Mixed-effects Models Using S4 Classes. R Package Version 0.999375-42. Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4

- Beckwith C. S. (1938). Sparganothis sulfureana Clem., a cranberry pest in New Jersey. J. Econ. Entomol. 31, 253–256 [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. A., Owens C. D., Shapiro M., Tardiff J. R. (1981). “Development of mass rearing technology,” in The Gypsy Moth: Research Toward Integrated Pest Management, eds Doane C. C., McManus M. L. (Washington: US Department of Agricultural; ), 599–633 [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M. A., Campbell C. A. M., Chamberlain K., Guerrieri E., Hick A. J., Martin J. L., et al. (2000). New roles for cis-jasmone as an insect semiochemical and in plant defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9329–9334 10.1073/pnas.160241697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland W., Gäbler A., Gilbert M., Feng Z. (1998). Biosynthesis of C11 and C16 homoterpenes in higher plants; stereochemistry of the C-C-bond cleavage reaction. Tetrahedron 54, 14725–14736 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00902-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boughton A. J., Hoover K., Felton G. W. (2006). Impact of chemical elicitor applications on greenhouse tomato plants and population growth of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 120, 175–188 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00443.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma M., Ijdema H., Van Loon J. J. A., Dicke M. (2008). Differential effects of jasmonic acid treatment of Brassica nigra on the attraction of pollinators, parasitoids, and butterflies. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 128, 109–116 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00695.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma M., Posthumus M. A., Mumm R., Mueller M. J., Van Loon J. J. A., Dicke M. (2009). Jasmonic acid-induced volatiles of Brassica oleracea attract parasitoids: effects of time and dose, and comparison with induction by herbivores. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2575–2587 10.1093/jxb/erp101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma M., Van Dam N. M., Van Loon J. J., Dicke M. (2007). Jasmonic acid-induced changes in Brassica oleracea affect oviposition preference of two specialist herbivores. J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 655–668 10.1007/s10886-006-9245-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab E. W., Kaspi R., Savchenko T., Rowe H., Negre-Zakharov F., Kliebenstein D., et al. (2008). Distinct roles of jasmonates and aldehydes in plant-defense responses. PLoS ONE 3:e1904. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollini D., Jr., Redman A. (1999). Age-dependent effects of jasmonic acid treatment and wind exposure on foliar oxidase activity and insect resistance in tomato. J. Chem. Ecol. 25, 271–281 10.1023/A:1020842712349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollini D., Purrington C. B., Bergelson J. (2003). Costs of induced responses in plants. Basic Appl. Ecol. 4, 79–89 10.1078/1439-1791-00134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper W. R., Goggin F. L. (2005). Effects of jasmonate-induced defenses in tomato on the potato aphid, Macrosiphum euphorbiae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 115, 107–115 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2005.00289.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Moraes C. M., Mescher M. C., Tumlinson J. H. (2001). Caterpillar-induced nocturnal plant volatiles repel conspecific females. Nature 410, 577–580 10.1038/35069058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denno R. F., Peterson M. A., Gratton C., Cheng J., Langellotto G. A., Huberty A. F., et al. (2000). Feeding-induced changes in plant quality mediate interspecific competition between sap-feeding herbivores. Ecology 81, 1814–1827 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[1814:FICIPQ]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dicke M., Gols R., Ludeking D., Posthumus M. (1999). Jasmonic acid and herbivory differentially induce carnivore-attracting plant volatiles in lima bean plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 25, 1907–1922 10.1023/A:1020942102181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dicke M., Vet L. E. M. (1999). “Plant-carnivore interactions: evolutionary and ecological consequences for plant, herbivore and carnivore,” in Herbivores: Between Plants and Predators, eds Olff H., Brown V. K., Drent R. H. (Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; ), 483–520 [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N., Klempien A., Muhlemann J. K., Kaplan I. (2013). Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol. 198, 16–32 10.1111/nph.12145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbilgin N., Krokene P., Christiansen E., Zeneli G., Gershenzon J. (2006). Exogenous application of methyl jasmonate elicits defenses in norway spruce (Picea abies) and reduces host colonization by the bark beetle Ips typographus. Oecologia 148, 426–436 10.1007/s00442-006-0394-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer E. E., Johnson R. R., Ryan C. A. (1992). Regulation of expression of proteinase inhibitor genes by methyl jasmonate and jasmonic acid. Plant Physiol. 98, 995–1002 10.1104/pp.98.3.995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton G. W., Korth K. L. (2000). Trade-offs between pathogen and herbivore resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 309–314 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00086-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgi L., Johnson-Cicalese J., Honig J., Das S. P., Rajah V. D., Bhattacharya D., et al. (2013). The first genetic map of the American cranberry: exploration of synteny conservation and quantitative trait loci. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126, 673–692 10.1007/s00122-012-2010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gols R., Posthumus M. A., Dicke M. (1999). Jasmonic acid induces the production of gerbera volatiles that attract the biological control agent Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 93, 77–86 10.1046/j.1570-7458.1999.00564.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gols R., Roosjen M., Dijkman H., Dicke M. (2003). Induction of direct and indirect plant responses by jasmonic acid, low spider mite densities, or a combination of jasmonic acid treatment and spider mite infestation. J. Chem. Ecol. 29, 2651–2666 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000008010.40606.b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare J. D. (2007). Variation in herbivore and methyl jasmonate-induced volatiles among genetic lines of Datura wrightii. J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 2028–2043 10.1007/s10886-007-9375-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare J. D. (2011). Ecological role of volatiles produced by plants in response to damage by herbivorous insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 161–180 10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil M. (2004). Induction of two indirect defences benefits lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus, fabaceae) in nature. J. Ecol. 92, 527–536 10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00890.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heil M. (2010). Plastic defence expression in plants. Evol. Ecol. 24, 555–569 10.1007/s10682-009-9348-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T., Bretz F., Westfall P. (2008). Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometr. J. 50, 346–363 10.1002/bimj.200810425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karban R., Baldwin I. T. (1997). Induced Responses to Herbivory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A., Baldwin I. T. (2001). Defensive function of herbivore-induced plant volatile emissions in nature. Science 291, 2141–2144 10.1126/science.291.5511.2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H. K., Rohmer M., Schwender J. (1997). Two independent biochemical pathways for isopentenyl diphosphate and isoprenoid biosynthesis in higher plants. Physiol. Plant. 101, 643–652 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb01049.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.-B., Liu S.-S., Liu Y.-Q., Furlong M. J., Zalucki M. P. (2004). Contrary effects of jasmonate treatment of two closely related plant species on attraction of and oviposition by a specialist herbivore. Ecol. Lett. 7, 337–345 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00582.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malo E. A., Castrejón-Gómez V. R., Cruz-López L., Rojas J. C. (2004). Antennal 20 sensilla and electrophysiological response of male and female Spodoptera frugiperda 21 (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to conspecific sex pheromone and plant odors. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 97, 1273–1284 10.1603/0013-8746(2004)097[1273:ASAERO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum E. J., Cunningham J. P., Lucker J., Zalucki M. P., De Voss J. J., Botella J. R. (2011). Increased plant volatile production affects oviposition, but not larval development, in the moth Helicoverpa armigera. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3672–3677 10.1242/jeb.059923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Z. J., Yan S. C., Yang C. P., Jin H., Hu X. O. (2011). Behavioural responses of Dendrolimus superans and Anastatus japonicus to chemical defences induced by application of jasmonic acid on larch seedlings. Scand. J. Forest Res 26, 53–60 10.1080/02827581.2010.533689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omer A. D., Granett J., Karban R., Villa E. M. (2001). Chemically-induced resistance against multiple pests in cotton. Int. J. Pest Manag. 47, 49–54 10.1080/09670870150215595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omer A. D., Thaler J. S., Granett J., Karban R. (2000). Jasmonic acid induced resistance in grapevines to a root and leaf feeder. J. Econ. Entomol. 93, 840–845 10.1603/0022-0493-93.3.840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa R., Shiojiri K., Sabelis M. W., Arimura G., Nishioka T., Takabayashi J. (2004). Corn plants treated with jasmonic acid attract more specialist parasitoids, thereby increasing parasitization of the common armyworm. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 1797–1808 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000042402.04012.c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré P. W., Tumlinson J. H. (1999). Plant volatiles as a defense against insect herbivores. Plant Physiol. 121, 325–332 10.1104/pp.121.2.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price P. W., Bouton C. E., Gross P., McPheron B. A., Thompson J. N., Weis A. E. (1980). Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11, 41–65 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2012). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; ISBN 3-900051-07-0. Available at: URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Raguso R. A., Levin R. A., Foose S. E., Holmberg M. W., McDade L. A. (2003). Fragrance chemistry, nocturnal rhythms and pollination ‘syndromes’ in Nicotiana. Phytochemistry 63, 265–284 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00113-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Saona C. (2011). Herbivore-induced blueberry volatiles and intra-plant signaling. J. Vis. Exp. 58, e3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Saona C., Blaauw D. R., Isaacs R. (2012). “Manipulation of natural enemies in agroecosystems: Habitat and semiochemicals for sustainable insect pest control,” in Integrated Pest Management and Pest Control – Current and Future Tactics, eds Larramendy M. L., Soloneski S. (Rijeka: In Tech; ), 89–126 [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Saona C., Crafts-Brandner S. J., Paré P. W., Henneberry T. J. (2001). Exogenous methyl jasmonate induces volatile emissions in cotton plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 27, 679–695 10.1023/A:1010393700918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Saona C., Poland T. M., Miller J. R., Stelinski L. L., Grant G. G., De Groot P., et al. (2006). Behavioral and electrophysiological responses of the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis, to induced volatiles of Manchurian ash, Fraxinus mandshurica. Chemoecology 16, 75–86 10.1007/s00049-005-0329-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]