Abstract

Xeroderma pigmentosum-variant (XPV) is one type of XP, a rare autosomal recessive disorder, and caused by defects in the post replication repair machinery while nucleotide-excision repair (NER) is not impaired. In the present study, we reported a Chinese family with XPV phenotype, which was confirmed by histopathological results. Genetic variants were detected by polymerase chain reaction and exon sequencing. Furthermore, the reported molecular defects in XPV patients from previous literatures were reviewed. A homozygous c.67C>T mutation in the exon 2 of DNA polymerase eta (POLH), a novel non-sense mutation in POLH, was discovered.

Keywords: POLH, Xeroderma Pigmentosum

Introduction

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by sun sensitivity, photophobia, early onset of freckling, and subsequent neoplastic changes on sun-exposed skin. Seven XP complementation groups (XPA to XPG), as well as variant (XPV), have been revealed. XPA through XPG group represents defective in NER, which is responsible for the removal of UV-induced damage in genomic DNA. The XPV (OMIM 278750) is caused by defects in the post replication repair machinery while NER is not impaired. XPV patients may display sunlight-induced pigmentation changes and a highly elevated incidence of skin malignancies, but rarely have neurological abnormalities1,2. The POLH gene (NM_006502.2), located on chromosome 6p21.1-6p12.3, has 11 exons spread over encodes a Y-family DNA polymerase eta (Pol η, NP_006493) that enables the cells to synthesize the correct daughter strands for translesion synthesis, despite the presence of thymine dimmers, on to the UV-damaged template DNA3.

In the present study, we reported a Chinese family with XPV phenotype and identified a novel nonsense mutation in POLH- that may lead to XPV.

Patients and methods

A 27-year-old man was admitted due to an unusually increased number of freckle-like pigmentation in sun-exposed areas, occurred when he was 4-month old. No photophobia or ocular lesion was noted. The patient was a computer engineer and had no neurological abnormalities. Review of family history revealed no similar patient. However, it was noted that he was born to consanguineous healthy parents and his parents were first cousins (Fig. 1A). We collected the data of the patient's clinical history, clinical findings and laboratory results.

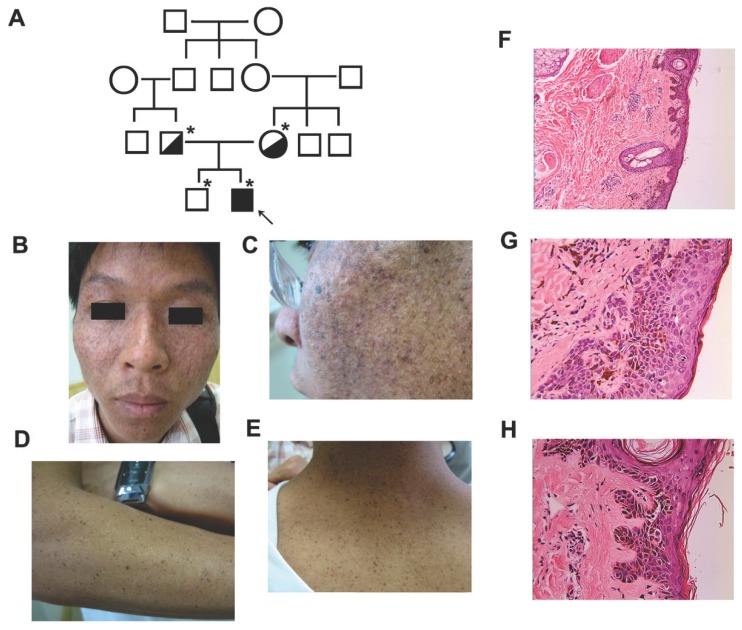

Figure 1.

Clinical features of the affected individual with XPV. (A) Pedigree of the reported family with XPV. An asterisk indicated that a blood sample was available. An arrow indicated the proband. (B-E) Clinical presentations of the affect individual with XPV phenotype showed diffuse cutaneous pigmentation and atrophy on the face and scattered small darken freckles on the nose, zygoma, neck and forearms. (F-H) Histological examination of a skin biopsy of facial lesion showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and atypic keratinocytes. Epidermal ridges elongated as bud-like and extended into the dermis.

A skin biopsy from facial lesion was performed and the sample was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Four-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Peripheral blood samples were collected from the affected patient and the unaffected family members, including his parents and brother, as well as 100 healthy controls. Genomic DNA was extracted using DNA extraction kit (Omega, Madison WI, USA). The DNA samples were delivered to Invitrogen Company (Shanghai, China), then were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequenced by ABI PRISM 3730 automated sequencer. To confirm whether genetic variants in genes involved in XP may be responsible for the affected family, we sequenced xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group C (XPC), damage-specific DNA binding protein 2 (DDB2), excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 4 (ERCC4) and POLH that lead to XPC, XPD, XPF and XPV, which have no neurological involvement.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University. All patients and healthy controls gave their written informed consents.

Results

On examination, the patient showed diffuse cutaneous pigmentation and atrophy on the face and scattered small darken freckles on the nose, zygoma, neck and forearms. No basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or melanoma lesions were seen in the affected areas (Fig. 1B-E). A skin biopsy of facial lesion showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and atypic keratinocytes with increased melanin granules, abnormally large nuclei and disorder to some degrees. Epidermal ridges elongated as bud-like and extended into the dermis. Some disseminated melanophages in the superficial layer of dermis and a mild perivascular mononuclear infiltration were observed (Fig. 1F-H).

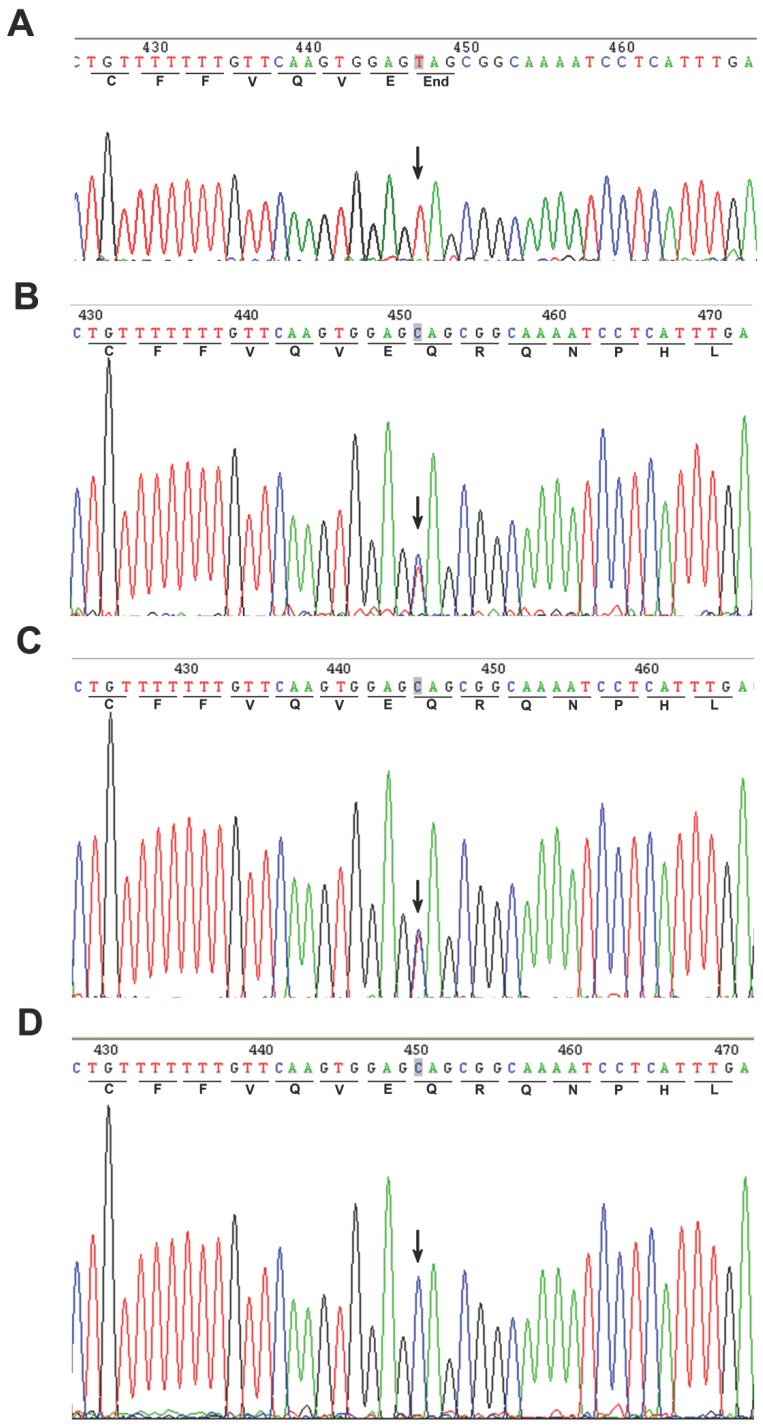

A homozygous c.67C>T mutation in the exon 2 of POLH was noted in the affected patient (Fig. 2A). The parents showed a heterozygous c. 67C>T mutation (Fig. 2B and C), while the genotype of the unaffected sibling is CC (Fig. 2D). In addition, we screened 100 unrelated control subjects and none had this mutation (data not shown), indicating that this mutation was not a common polymorphism but a novel pathological mutation of POLH in the affected family. We sequenced other causal genes implicated in other XP groups, including the xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group C (XPC/XPC), damage-specific DNA binding protein 2 (DDB2/XPD) and excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 4 (ERCC4/XPF) genes. We did not identify genetic variants in these genes that may cause XP in this affected family (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Direct sequencing of the PCR products amplified from exon 2 of the POLH gene. An arrow showed the position of mutated base. (A) Homozygous mutation of C>T in the coding region at nucleotide position 67 in the proband's sequence. (B-C) Heterozygous c.67C>T mutation was found in the parents. (D) The sequence of unaffected sibling was reference homozygote.

Discussion

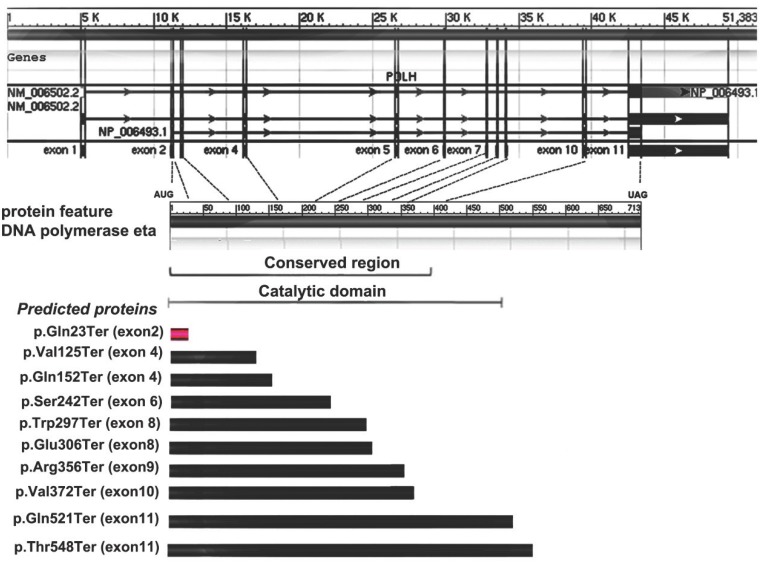

Allelic variants listed in OMIM (http://omim.org/entry/603968) and reported in previous literatures have revealed some molecular defects in XPV patients from America, Europe, Africa and Asia (mainly from Japan)1-10. Of these, ten are missense mutations, nine are nonsense and twenty-one represent frameshift or large deletion. Furthermore, four types of possible founder mutations, c.490G>T, c. del1661A, c.916G>T and c.725C>G, are responsible for 87% Japanese patients with XPV9. Among the nonsense mutations detected previously, all of them are in exons 4-11 and none is from the exon 2, which are inside the conserved region and catalytic domain of Pol η (Fig. 3). Here, a novel point mutation - c.67C>T in the exon 2 of POLH, leading to a nonsense mutation (p.Gln23Ter) -was identified (Fig. 3), which was not reported previously. Furthermore, the different predicted protein sizes associated to each nonsense mutation in the present study and the reviewed XPV patients were shown in the Fig.3.

Figure 3.

Gene and protein feature of Pol η, and nonsense mutation spectrum of POLH gene and predicted proteins in XPV cells. The first part showed the 11 exons of POLH gene. The 713 amino-acid Pol η protein and the indicated conversed region or catalytic domain was shown in the second part. The third part showed the different predicted protein sizes associated to each nonsense mutation in the present study (red) and the reviewed XPV patients (black).

One mechanism for the observed large reduction in polη protein would be nonsense-mediated message decay11. An XPV cell strain with a nonsense mutation in the POLH gene had no detectable polη protein levels and showed about 50% of normal POLH mRNA levels. Thus, we inferred that, in the present case, the novel nonsense mutation of POLH may result in message decay and further loss of polη protein, responsible for the high frequency and abnormal spectrum of UV-induced mutations, and ultimately their malignant transformation, which needs further in vitro and in vivo functional experiments to confirm. It was ever revealed that mutations outside the catalytic domain of Pol η is always associated with a very mild phenotype compared with those inside the catalytic domain regardless of the mutation type8,9. While it was also believed by other researchers that wild variability in clinical features among XPV patients was not obviously related to the site or type of mutation10. In addition to the localization of the mutation, the incidence of skin cancer in XPV patients might be related to accumulation of sun exposure, life style of a patient and other genetic determinants9. An actinic keratosis, the most common precancer, had been observed in the present patient till now. Therefore, it is important for him to improve his life style, such as sun protection and being away from caffeine.

In summary, we have identified a novel nonsense mutation in POLH leading to XPV in an affected family and extend the genetic mutation spectrum of XPV.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the XPV family and healthy volunteers for their cooperation in this study. This work was supported financially in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants (No. 81000761).

Abbreviation

- XP

xeroderma pigmentosum

- XPV

xeroderma pigmentosum-variant

- NER

nucleotide-excision repair

- POLH

DNA polymerase eta.

References

- 1.Tanioka M, Masaki T, Ono R. et al. Molecular analysis of DNA polymerase eta gene in Japanese patients diagnosed as xeroderma pigmentosum variant type. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1745–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inui H, Oh KS, Nadem C. et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients from America, Europe, and Asia. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2055–68. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuasa M, Masutani C, Eki T. et al. Genomic structure, chromosomal localization and identification of mutations in the xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XPV) gene. Oncogene. 2000;19:4721–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh T, Linn S, Kamide R. et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant heterozygotes show reduced levels of recovery of replicative DNA synthesis in the presence of caffeine after ultraviolet irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:981–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Pol eta. Science. 1999;283:1001–4. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Yamada A. et al. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase eta. Nature. 1999;399:700–4. doi: 10.1038/21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada A, Masutani C, Iwai S. et al. Complementation of defective translesion synthesis and UV light sensitivity in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells by human and mouse DNA polymerase eta. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2473–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben Rekaya M, Messaoud O, Mebazaa A. et al. A novel POLH gene mutation in a xeroderma pigmentosum-V Tunisian patient: phenotype-genotype correlation. J Genet. 2011;90:483–7. doi: 10.1007/s12041-011-0101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masaki T, Ono R, Tanioka M. et al. Four types of possible founder mutations are responsible for 87% of Japanese patients with Xeroderma pigmentosum variant type. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;52:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broughton BC, Cordonnier A, Kleijer WJ. et al. Molecular analysis of mutations in DNA polymerase eta in xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:815–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022473899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuzmiak HA, Maquat LE. Applying nonsense-mediated mRNA decay research to the clinic: progress and challenges. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:306–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]