Abstract

The Brazilian agro-industrial frontier in Mato Grosso rapidly expanded in total area of mechanized production and in total value of production in the last decade. This article shows the spatial pattern of that expansion from 2000 to 2010, based on novel analyses of satellite imagery. It then explores quantitatively and qualitatively the antecedents and correlates of intensification, the expansion of the area under two crops per year. Double cropping is most likely in areas with access to transportation networks, previous profitable agricultural production, and strong existing ties to national and international commodity markets. The article concludes with an exploration of the relationship between double cropping and socioeconomic development, showing that double cropping is strongly correlated with incomes of all residents of a community and with investments in education. We conclude that double cropping in Mato Grosso is very closely tied to multiple indicators of socioeconomic development.

Keywords: double cropping, agricultural intensification, economic development, Mato Grosso

1. Introduction

The intensification of agriculture in South America and elsewhere has been framed in international environmental science as a potentially land-sparing process [1–3], but it is framed in public debate and by some scholars as a development issue [4,5]. Agricultural intensification both permits a decoupling of agricultural production and deforestation [6], and increases profits per unit area of land [7]. Intensive, mechanized agriculture depends on infrastructure and a skilled labour force, but also increases local land values and returns to labour [8,9]. Potential outcomes of increasing farm values, farmworker incomes and specialization in the labour market include demand for local labour in complementary economic sectors, demand for education and higher tax revenues. This article shows how economic development and agricultural intensification go hand-in-hand in Mato Grosso.

Intensification of agriculture presents a dilemma for development, with a priori uncertain socioeconomic and environmental outcomes [10]. The fundamental premise of agrarian reform in Brazil and throughout Latin America is that familial agriculture systems, characterized by relatively equal land distributions, and production for family needs as well as for markets, promote well-being and an engaged citizenry [11–13]. Yet observations and theories of modern economies show that consolidation of farming into larger operations, which take advantage of economies of scale and verticalize agricultural processing (i.e. install local processing for agricultural products), lead to overall economic growth [14]. Critics argue that the benefits of this economic growth are reaped by the elite or by outside investors, and not by local residents or farm workers [4,15]. However, if this growth benefits the population through rising incomes and provision of public goods such as schools, healthcare and public safety, it has the potential to be dramatically more beneficial than the wealth and food security associated with owning a family farm.

This article presents a series of quantitative and qualitative analyses to empirically address the relationship between agricultural intensification and socioeconomic development. We start by mapping the expansion of mechanized agriculture in Mato Grosso between 2000 and 2010, distinguishing areas with one harvest per year from those with two harvests per year. We then quantitatively examine the association between socioeconomic indicators in the year 2000 with subsequent changes in area in mechanized agriculture, and qualitatively show key social and institutional dynamics leading to divergent outcomes in two case study communities. We then show quantitatively the association between level of agricultural intensification and a suite of indicators of socioeconomic development across Mato Grosso at the end of the last decade. We conclude with a discussion of future research directions and policy recommendations.

2. Intensification of agriculture across Mato Grosso

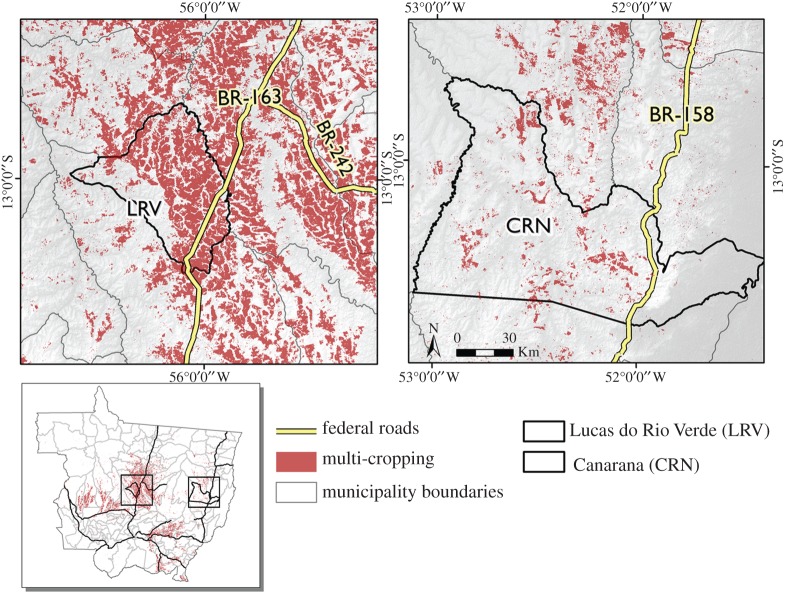

Figure 1 provides a novel mapping of the extent and distribution of intensive agriculture in Mato Grosso. All areas identified as agriculture are mechanized row crop production, and single cropping is one harvest per year, whereas double cropping is two harvests per year. Crop rotations in double-cropping systems are most often soya bean–corn, and are soya bean–cotton in a minority of cases [16]. These areas were identified from Terra moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) remotely sensed data by analysing the phenology (change in plant vigour over time) of each pixel over each growing year. We use the enhanced vegetation index from each 16-day period in each agricultural year as a measure of greenness or vegetation health in each pixel, and then look for patterns across the growing year characteristic of non-agricultural uses, single-crop agriculture (a single peak of greenness) or double-crop agriculture (two peaks of greenness). This approach has been used widely in recent work to study mechanized agriculture because of the rapid greenup and loss of greenness that characterize mechanized planting and harvesting [17,18]. Details of the approach are shown in the supplemental material and in other work in progress [16]. We calculate an overall accuracy of 87 per cent using field validation points (see the electronic supplementary material) and our estimates of the total area in mechanized agriculture in the 2000–2001 (38 850 km2, comprising 23 780 km2 in single cropping and 15 070 km2 in double cropping) and 2010–2011 (69 421 km2, comprising 26 042 km2 in single cropping and 43 379 km2 in double cropping) growing seasons are very close to other published estimates [17,18].

Figure 1.

Mechanized single and double cropping, Mato Grosso, 2000–2010. Years refer to the initial year of the growing season (e.g. 2000 is the 2000–2001 growing season). This figure shows the state of Mato Grosso, with background colours indicating the biome (according to the WWF). Areas of mechanized agriculture with a single crop harvested per year are shown in purple and areas of mechanized agriculture with more than one crop harvested per year are shown in orange.

These maps show that the process of mechanization of agriculture was already underway in 2000, with patches across much of the centre and south of the state. The move to double cropping was heavily focused in the centre of the state, around the municípios (equivalent to counties) of Lucas do Rio Verde and Sorriso, and in the southeast, around the município of Primavera do Leste. Investment continued in the areas already mechanized and double cropping expanded from its original foci by 2010. In 2010, we can see what an expert informant identified as the five areas of multi-cropping in the state (which Arvor et al. group in four areas [18]). The original two clusters are joined by two areas in the centre-west of the state and a line of intensification on the eastern side of the state. This clustering suggests that the process of conversion to double cropping builds on certain pre-existing characteristics of regions, and also provides the spatial variation in the extent of double cropping on which we draw to analyse the socioeconomic antecedents and correlates of double cropping in this article.

3. Development of county-level double cropping

Existing literature on the spread of deforestation and agropastoral land use in the Brazilian Amazon has pointed to the importance of roads and population growth through in-migration and settlement [19,20]. Export-oriented soya bean production in Mato Grosso does not necessarily follow this same pattern. Over time, the expansion of soya bean production is driven by macroeconomic factors including global prices and the devaluation of the Brazilian real [21]. Spatial variation is argued to follow from biophysical properties of the landscape and from variation in availability of inputs and markets [22]. Mechanization is only possible on flat lands and soya bean in Mato Grosso grows on very flat lands and at higher elevations [23]. Case study research in Brazil suggests that the organization of markets and the size of the agricultural sector in a community are important drivers of mechanization and soya bean profitability [24].

We combine these previously studied characteristics of areas in a single regression model of the spatial variation in the extent of double cropping in municípios in 2010. We merge data from multiple sources to generate measures of roads, population size, prior agricultural and non-agricultural gross domestic product (GDP), and biophysical suitability. The log of the proportion of the município in double cropping in 2010 is regressed on these variables measured for 2000, controlling for the single and double cropping in 2000 and for spatial autocorrelation. We use a three-category variable to measure roads, indicating the presence of a federal highway in the município, in a neighbouring município, or neither. (These highways are indicated in bold in the inset map in figure 3 below.) We measure population size from the 2000 census of population and use the município GDP in 2000 divided into agricultural and non-agricultural GDP. Full regression results are available in the electronic supplementary material. Figure 2 shows the results graphically, showing the predicted proportion of area in double cropping across the range of key variables with other variables held at their mean or mode.

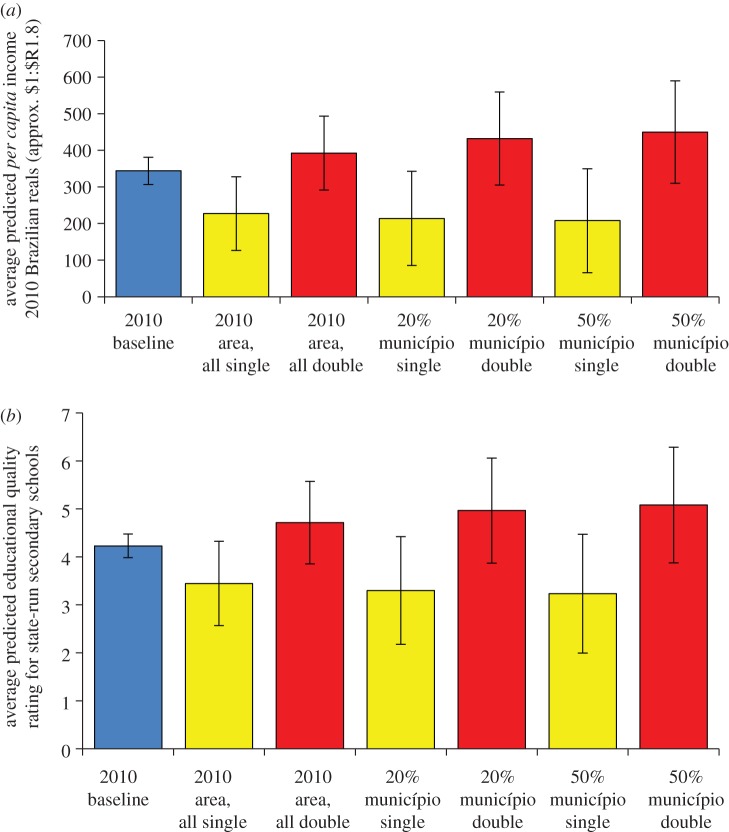

Figure 3.

Case study municípios, Lucas do Rio Verde and Canarana.

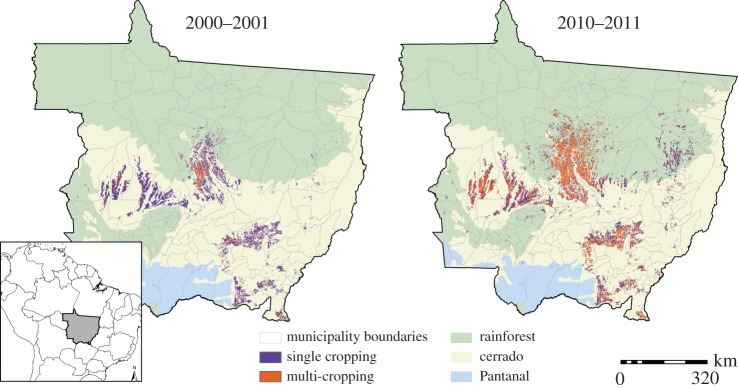

Figure 2.

Predicted proportion double-cropped across ranges of highway access and GDP. Predictions are for a município with land use in 2000 at mean values for each class, control variables set at their means (or to category of no federal highway access), and GDP and road access variables systematically varied over their range. Solid line, agricultural GDP in 2000, in 1000's of reals; dashed line, non-agricultural GDP in 2000, in 1000's of reals.

Figure 2 shows that road access is positively associated with expansion of intensive agriculture. Results in the electronic supplementary material show the relationship of the biophysical characteristics and the extent of the spatial autocorrelation in double cropping, even after controlling for observed variables. The strongest relationship between a socioeconomic indicator and double cropping is seen for prior agricultural GDP, even after controlling for the area of single and double cropping in 2000. This result suggests that it is not simply that double cropping is increasing where it got an early start, or where mechanized agriculture has taken hold early, but that the complementary investments in agricultural processing and services are associated with the concentrated expansion of double cropping in clusters of municípios. This story is very consistent with that told by Garrett et al. [24], in which all the complementary institutions are key for farmers to make a large profit.

We turn now to a qualitative examination of such institutional development and double cropping, showing how it moves with other important aspects of socioeconomic development. Case study material from two municípios in Mato Grosso shows the gradual process of investment that gains momentum and results in current patterns. Our case study municípios are Lucas do Rio Verde (LRV), in the centre of the state, and Canarana (CRN), in the emerging eastern band of double cropping. We draw on published materials as well as on interviews and field research conducted in each of these two municípios by one coauthor (R.d.S.) during 2010 and 2011. A full description of fieldwork is beyond the scope of this article; however, a summary is included in the electronic supplementary material. Figure 3 shows that the extent of double cropping is greater in LRV than in CRN, despite CRN having incipient intensification. Incomes are also higher: the overall GDP in 2009 is $R1 809 788 155 in LRV compared with $R327 445 521 in CRN, whereas per capita GDP and per capita monthly household income are $R53 933 versus $R18 177, and $R600 versus $R440, respectively, for LRV compared with CRN.

These two municípios started in similar ways. Both have access to federal highways and were settled by cooperatives of farmers from the south of Brazil in the 1970s. Both are in regions with relatively flat topography and amenable soils, evidenced in part by the fact that both are currently home to extensive mechanized agriculture. Almost 90 per cent of CRN is above 300 m elevation and less than 1 degree of slope, our definition of desirable for mechanized agriculture (see the electronic supplementary material for more detail). LRV is almost 100% suitable. Both were characterized by largeholder agriculture or ranching from their inception. They both are in the cerrado–Amazon transition zone and are at roughly the same latitude in a state where the precipitation gradient runs north–south.

The core of our analysis shows that the crux of the difference in trajectories between LRV and CRN was an investment of capital and entry of economic networks into LRV in the 1980s. Initial differences in capital made this investment more desirable, but the ability of people in LRV to leverage external investments was the core of their recent success. Southern Brazilian families following the BR-163 highway construction first settled in LRV in 1976. These moderately capitalized families acquired semi-legal land titles on lots ranging from 1000 to 5000 ha, which they largely were able to maintain through a 1981 government colonization project to bring families from Rio Grande do Sul [25]. In 1985, the São Paulo-based cooperative Cooperlucas selected 50 families for a second LRV settlement project focused on soya bean farming. Selection was based on assets and farming experience, and the programme has been described as ‘elite agrarian reform’ [26]. PRODECER (The Japanese–Brazilian Cooperative Programme for Cerrado Development) financed the project, and its implementation importantly linked LRV to industrialized agriculture and external soya bean demand.

CRN is located 35 km from the BR-158 highway, and was founded in 1972 by a Lutheran colonization cooperative from Rio Grande do Sul [27]. A total of 81 families settled in the county, each with assets of between $1500 and $28 000. They were able to access credit by virtue of the cooperative's immediate land title guarantee [28]. These families purchased 480 ha (on average) in CRN, a smaller average landholding than in LRV. Interviews suggest that settlers in CRN were slightly less well-off than those in LRV, despite their access to credit and title.1 More importantly, however, agriculture in LRV acquired an industrial tone and link to external commodity and investment markets with the arrival and assets of the PRODECER colonists, whereas CRN lacked those connections during the same time period.

Two important processes began as a result of these early differences. First, the level of mechanization has been higher in LRV than in CRN since very early in the settlement process, with a larger number of tractors and large trucks in LRV than in CRN in the 1995/6 agricultural census [29]. Second, farmers in LRV concentrated on soya bean production in the 1980s, whereas landholders in CRN concentrated on ranching. While settlers in CRN were advantaged in access to credit by having secure land title, they were led into ranching by subsidized agricultural credit for cattle and credit that was contingent on demonstrated ‘productive use’ of land. LRV, by contrast, focused on soya bean production and industrial linkages [30], and in 1992 founded a regional agricultural research organization, the Fundação Rio Verde (FRV). The FRV focused on region-specific crop research, recognizing that Embrapa, the national public–private agricultural research organization, did not yet work in their area. FRV has published technical bulletins after each harvest since 2000, and hosts two annual agricultural research and demonstration fairs that bring multinational companies to the county.

The cascading consequences from initial differences in its settlement process and capitalization put LRV on a path to be ready to attract external capital at the moment that Brazil's soya bean boom was beginning. Richards et al. [21] trace the expansion of Brazil's soya bean production to the devaluation of the real in the late 1990s and early 2000s. During this time, politicians and businesspeople from LRV worked with many other stakeholders to attract outside investments profitable to agriculture in LRV. These included Cargill's construction of the soya bean export processing facility in Santarém at the northern end of the BR-163 highway (first opened in 2003), federal investment in the paving of the BR-163 between LRV and Santarém (begun in the early 2000s but still incomplete), the installation of confined chicken-raising facilities around the município (begun mid-2000s), the installation in LRV of an incubator capable of hatching 1 million chicks per day (2005), and the construction in LRV of a meatpacking plant capable of processing 500 000 chickens per day (2007). The local government–industry partnership involves corporate-subsidized housing, and subsidies to school, sanitation and electricity infrastructure.

4. Intensification and socioeconomic development

The preceding sections show how socioeconomic development accompanied or set the stage for the expansion of mechanized agriculture and double cropping. This section looks across municípios and estimates how município-to-município differences in 2010 extent of single and double cropping are associated with contemporaneous differences in income and public provision of services. We use two indicators of well-being here; additional indicators are shown in the electronic supplementary material. First, we examine the median monthly per capita household income measured in the 2010 census of population [31]. The median captures the experience of the average household in the community by minimizing the influence of outliers on the high end of the income distribution. Thus, we are not measuring simply the effects of double cropping on the income of a small group of wealthy landowners. This measure comes from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [32]. Second, we use an index of school quality called the Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica (basic education development index; IDEB) estimated by the Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais and used by the Brazilian Ministry of Education for evaluation and target setting. It includes performance on end-of-level standardized tests and time to completion of a level [33]. We use this index value for state-run secondary schools in 2009. Unlike income, which merely captures personal or household well-being, this variable captures investments in a key public good.

To examine these key measures, we estimated regression models of each outcome at the município level. In each case, we used cross-sectional spatial-autoregressive models with spatial-autoregressive disturbances to account for spatial dependence in the process under study [34,35]. Right-hand side variables include the log of the proportion of the município in single cropping, the log of the proportion of the município in double cropping, and controls for the log of population, the percent urban, road access and biophysical characteristics of the município. The details of these measures and regression models, as well as models of alternative indicators of socioeconomic development are provided in the electronic supplementary material. Figure 4 presents key results of estimated models using a simulation approach. We simulate changes in município single and double cropping and then predict the associated differences in socioeconomic development from the estimated regression equations. Each panel shows the average predicted value for the outcome (median per capita household income or school quality index) for municípios taking nine sets of values for single and double cropping. In each case, they maintain their true values on all other variables. We predict the outcomes if they have their true values of single and double cropping (which reproduces the sample means), if they maintain their true proportion of area in mechanized agriculture but devote it all to either single or double cropping and if they take 20 or 50 per cent of their area entirely in either single or double cropping.

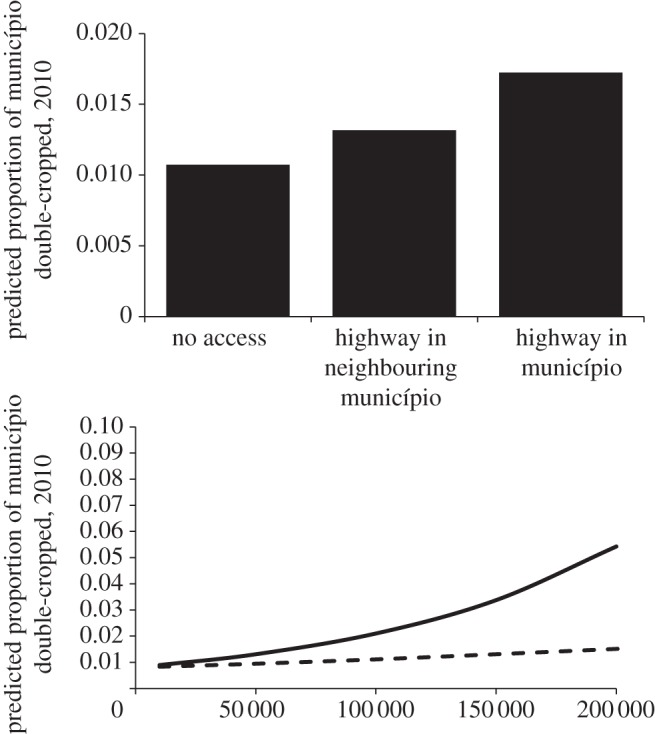

Figure 4.

(a) Predicted median per capita income and (b) educational quality under simulated levels of agricultural intensification. Microsimulations were conducted by setting the values of single or double cropping to those specified, maintaining true values for all other variables, and then predicting the value of income or IDEB and the s.e. of that prediction.

The values estimated under these counterfactual scenarios serve to illustrate the powerful development potential of intensive agriculture. The baseline Mato Grosso-wide measure of median monthly per capita income is 346 Brazilian reals (approximately $190 in 2010). In a scenario in which all municípios single-cropped all of their currently mechanized agricultural areas, this would be reduced to $R144, but were they to double crop all of their currently mechanized agricultural areas, it would increase to $R459. Figure 4 shows even further increases in the median monthly per capita income as the percent of area double-cropped increases from the 2010 mechanized area to 20 per cent, the legal limit of usable area at the farm level in the Amazon biome, and then to 50 per cent, below the legal limit of 65 per cent at the farm level in the cerrado biome.

Figure 4 shows a similar relationship of single and double cropping to public investment in secondary education. The theoretical range of the IDEB is 0–10, but municípios in Mato Grosso ranged from 3 to 5.7, with a mean of 4.2, for state-run secondary schools. Our models estimate that converting all currently mechanized agriculture to double cropping would increase that mean to 5.1 and that further increasing the area double-cropped to 20 per cent of each município could increase it to 5.4. Such an increase would be equivalent to the improvement seen in Mato Grosso between 2005 and 2009 during a nationwide campaign to improve school quality.

5. Conclusions: path dependence and promoting agriculture-led development

The analyses presented in this article have shown the strong association between the expansion of double cropping and public well-being. Double cropping and complementary institutions and economic activities go hand in hand, bringing employment, in-migration, income and investment in public goods. Prior economic investment in the agricultural sector, particularly in export-oriented production and processing, is associated with expansion of double cropping. Double cropping is then associated with positive outcomes for local incomes across economic sectors and across the income distribution, as well as with investment in public goods. The evidence presented here suggests that policies promoting export and the expansion of processing and marketing capabilities in Mato Grosso and beyond would bring about socioeconomic development across the state.

Yet, we should be cautious in drawing such universal lessons from the history to date of Mato Grosso and promoting, for example, blanket subsidies for double cropping. Our models show the historical coevolution of socioeconomic development and double cropping, but do not definitively establish causality. Research across Brazil shows the improvements and subsequent crash in the human development index associated with boom and bust cycles [36]. Soya bean production appears unlikely to experience a bust in the near future, but we need to invest further research effort to assess the likelihood of such a bust. We also need to acknowledge and further explore the potential spatial dispersion of the population associated with the expansion of ever-more-intensive agriculture. In many parts of the world, intensification pushes small farmers or agricultural labourers without the requisite skills into urban poverty or forest frontiers [9].

As we undertake this research, our comparative case study points to the need to integrate a historical and political economic view into our landscape- and population-wide models. We showed that small differences gain large importance over time, as they trigger cascades of changes in the social system in the same way small changes feedback to change ecosystems over time. The impact of these differences depends in underexamined ways on the macroeconomic and policy context. Our case study and others talk about the importance of what is perceived as luck in the moment: being in the right place at the right time, and being able to take advantage of larger forces to effect major local change. Such thinking is relatively rare in the most influential environmental science, which is tightly focused on drivers, causal relationships and policy levers that change the decision-making of individual farmers. To move such science forward, we must integrate the rich understandings of context and feedbacks within the social system that characterize much qualitative human geography and anthropology with the quantitative, regression-based models of the literature on the drivers of land use change. This article points to key processes to study in the search for a more complex understanding of social system feedbacks. The most important processes in the successful harnessing of agriculture for development involved flows of people (and their skills), financial capital, and institutions across the landscape. The changing distributions of these across space create new combinations and connections, changing the social system in which land use and development processes operate.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this research were supported by NASA grant no. NNX11AH91G, NIH grant no. R24-HD041020 and with financial and administrative assistance from the Environmental Change Initiative at Brown University. We also thank Lynn Carlson for assistance with data processing and maps, and Kelley Smith for editorial assistance. Finally, we are grateful to residents of Lucas do Rio Verde and Canarana who generously shared information about their history with us.

Endnote

Personal interview with Augusto Dunck, Canarana pioneer, and Domingos Finato, head of Radio Vida Nova Community Radio, 1 September, 2010.

References

- 1.Phalan B, Onial M, Balmford A, Green RE. 2011. Reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation: land sharing and land sparing compared. Science 333, 1289–1291 10.1126/science.1208742 (doi:10.1126/science.1208742) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilman D, Balzer C, Hill J, Befort BL. 2011. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20 260–20 264 10.1073/pnas.1116437108 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1116437108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudel TK, et al. 2009. Agricultural intensification and changes in cultivated areas, 1970–2005. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA 106, 20 675–20 680 10.1073/pnas.0812540106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0812540106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolford W. 2008. Environmental justice and the construction of scale in Brazilian agriculture. Soc. Nat. Res. 21, 641–655 10.1080/08941920802096432 (doi:10.1080/08941920802096432) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinelli LA, Garrett R, Ferraz S, Naylor R. 2011. Sugar and ethanol production as a rural development strategy in Brazil: evidence from the state of Sao Paulo. Agric. Syst. 104, 419–428 10.1016/j.agsy.2011.01.006 (doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2011.01.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macedo MN, DeFries RS, Morton DC, Stickler CM, Galford GL, Shimabukuro YE. 2012. Decoupling of deforestation and soy production in the southern Amazon during the late 2000s. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1341–1346 10.1073/pnas.1111374109 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1111374109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann ML, Kaufmann RK, Bauer D, Gopal S, Vera-Diaz MDC, Nepstad D, Merry F, Kallay J, Amacher GS. 2010. The economics of cropland conversion in Amazonia: the importance of agricultural rent. Ecol. Econ. 69, 1503–1509 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.02.008 (doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.02.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpentier CL, Vosti SA, Witcover J. 2000. Intensified production systems on western Brazilian Amazon settlement farms: could they save the forest? Agric Ecosyst. Environ. 82, 73–88 10.1016/S0167-8809(00)00217-6 (doi:10.1016/S0167-8809(00)00217-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards PD. 2012. Indirect land use change and the future of the Amazon. PhD dissertation, Michigan State University Department of Geography, East Lansing, MI [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee DR, Barrett CB. 2001. Tradeoffs or synergies? Agricultural intensification, economic development, and the environment. Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK: CABI Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittman H. 2009. Reframing agrarian citizenship: land, life and power in Brazil. J. Rural Stud. 25, 120–130 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.07.002 (doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.07.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolford W. 2010. Participatory democracy by default: land reform, social movements and the state in Brazil. J. Peasant Stud. 37, 91–109 10.1080/03066150903498770 (doi:10.1080/03066150903498770) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons C, Walker R, Perz S, Aldrich S, Caldas M, Pereira R, Leite F, Fernandes LC, Arima E. 2010. Doing it for themselves: direct action land reform in the Brazilian Amazon. World Dev. 38, 429–444 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.003 (doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiffin R, Irz X. 2006. Is agriculture the engine of growth? Agric. Econ. 35, 79–89 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2006.00141.x (doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2006.00141.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudel TK, Roberts JT, Carmin J. 2011. Political economy of the environment. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 37, 221–238 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102639 (doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102639) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spera S, Mustard J, Mahr D, Risso J, Adami M, Rudorff B, VanWey LK. Submitted. Methods for assessing agricultural intensification: the expansion of double cropping in Mato Grosso state, Brazil.

- 17.Galford GL, Mustard JF, Melillo J, Gendrin A, Cerri CC, Cerri CEP. 2008. Wavelet analysis of MODIS time series to detect expansion and intensification of row-crop agriculture in Brazil. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 576–587 10.1016/j.rse.2007.05.017 (doi:10.1016/j.rse.2007.05.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arvor D, Jonathan M, Penello Meirelles MS, Dubreuil V, Durieux L. 2011. Classification of MODIS EVI time series for crop mapping in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32, 7847–7871 10.1080/01431161.2010.531783 (doi:10.1080/01431161.2010.531783) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaff ASP. 1999. What drives deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon? Evidence from satellite and socioeconomic data. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 37, 26–43 10.1006/jeem.1998.1056 (doi:10.1006/jeem.1998.1056) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perz S, et al. 2008. Road building, land use and climate change: prospects for environmental governance in the Amazon. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 1889–1895 10.1098/rstb.2007.0017 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.0017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards PD, Myers RJ, Swinton SM, Walker RT. 2012. Exchange rates, soybean supply response, and deforestation in South America. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 22, 454–462 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.01.004 (doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.01.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vera-Diaz MdC, Kaufmann RK, Nepstad DC, Schlesinger P. 2008. An interdisciplinary model of soybean yield in the Amazon Basin: the climatic, edaphic, and economic determinants. Ecol. Econ. 65, 420–431 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.07.015 (doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.07.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jasinski E, Morton D, DeFries R, Shimabukuro Y, Anderson L, Hansen M. 2005. Physical landscape correlates of the expansion of mechanized agriculture in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Earth Interact. 9, 1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrett RD, Lambin EF, Naylor RL. 2013. Land institutions and supply chain configurations as determinants of soybean planted area and yields in Brazil. Land Use Policy 31, 385–396 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.08.002 (doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.08.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zart LL. 1998. Desencanto na Nova Terra: assentamento no municipio de Lucas do Rio Verde - MT na decada de 80. Master's thesis, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocha BN. 2008. Posse de Terra e Diferenciação Social em Lucas do Rio Verde (1970–1980). Presented at Identidades XIII Encontro de Historia Anpuh-Rio See http://encontro2008.rj.anpuh.org/resources/content/anais/1212958359_ARQUIVO_BettyRocha-GTTerraeConflito.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jepson W. 2006. Private agricultural colonization on a Brazilian frontier, 1970–1980. J. Hist. Geogr. 32, 839–863 10.1016/j.jhg.2004.12.019 (doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2004.12.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jepson W. 2006. Producing a modern agricultural frontier: firms and cooperatives in Eastern Mato Grosso, Brazil. Econ. Geogr. 82, 289–316 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2006.tb00312.x (doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2006.tb00312.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.IBGE 1995. Censo Agropecuario de 1995–1996: tabela 7—Maquinaria e veiculos existentes em 31.12.1995, segundo Mesorregioes, Microrregioes e Municipios—Mato Grosso. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional de Geografia e Estatistica; See http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/economia/agropecuaria/censoagro/1995_1996/51/d51_t07.shtm [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galvão A, Silveira JMFJ, Attie JE, Ferreira LM, Garcia J, Buainain AM, Andrade P. 2012. Desenvolvimento socioeconômico e a agricultura na América do Sul (Resumo Executivo). Uberlândia, Brasil: IE/UNICAMP-Celeres [Google Scholar]

- 31.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) 2010. Censo de População de 2010. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; See http://www.ibge.gov.br/censo2010/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.IBGE 2012. Censo 2010: tabela 3563—Domicílios particulares permanentes, Valor do rendimento nominal médio mensal per capita e mediano mensal per capita dos domicílios particulares permanentes, segundo a situação do domicílio e as classes de rendimento nominal mensal domiciliar. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional de Geografia e Estatistica See http://www.sidra.ibge.gov.br/bda/tabela/listabl.asp?c=3563&z=cd&o=16

- 33.Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Texeira (INEP) 2012. Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica. Brasília, Brazil: INEP See http://ideb.inep.gov.br

- 34.Drukker DM, Prucha IR, Raciborski R. 2011. Maximum-likelihood and generalized spatial two-stage least-squares estimators for a spatial-autoregressive model with spatial-autoregressive disturbances. Working Paper, Department of Economics, University of Maryland, MD [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeSage JP, Pace RK. 2009. Introduction to spatial econometrics. Boca Raton: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigues ASL, Ewers RM, Parry L, Souza C, Verissimo A, Balmford A. 2009. Boom-and-bust development patterns across the Amazon deforestation frontier. Science 324, 1435–1437 10.1126/science.1174002 (doi:10.1126/science.1174002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]