Abstract

Significance: The worldwide blood shortage has generated a significant demand for alternatives to whole blood and packed red blood cells for use in transfusion therapy. One such alternative involves the use of acellular recombinant hemoglobin (Hb) as an oxygen carrier. Recent Advances: Large amounts of recombinant human Hb can be expressed and purified from transgenic Escherichia coli. The physiological suitability of this material can be enhanced using protein-engineering strategies to address specific efficacy and toxicity issues. Mutagenesis of Hb can (i) adjust dioxygen affinity over a 100-fold range, (ii) reduce nitric oxide (NO) scavenging over 30-fold without compromising dioxygen binding, (iii) slow the rate of autooxidation, (iv) slow the rate of hemin loss, (v) impede subunit dissociation, and (vi) diminish irreversible subunit denaturation. Recombinant Hb production is potentially unlimited and readily subjected to current good manufacturing practices, but may be restricted by cost. Acellular Hb-based O2 carriers have superior shelf-life compared to red blood cells, are universally compatible, and provide an alternative for patients for whom no other alternative blood products are available or acceptable. Critical Issues: Remaining objectives include increasing Hb stability, mitigating iron-catalyzed and iron-centered oxidative reactivity, lowering the rate of hemin loss, and lowering the costs of expression and purification. Although many mutations and chemical modifications have been proposed to address these issues, the precise ensemble of mutations has not yet been identified. Future Directions: Future studies are aimed at selecting various combinations of mutations that can reduce NO scavenging, autooxidation, oxidative degradation, and denaturation without compromising O2 delivery, and then investigating their suitability and safety in vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 2314–2328.

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 103 million units of whole blood and packed red blood cells are donated every year (161a). In the United States alone, over 15 million units are transfused annually (159). These transfusions are often life saving (27, 29, 106, 154) and rarely cause serious adverse events, although side effects do occur (23, 37, 70, 71, 82, 105). However, most U.S. hospitals consistently report blood shortages (159), and studies predict that these shortages will worsen as the population ages (53, 130, 144, 164). This situation is more troubling in less-developed countries where blood donation rates are as low as 0.4 units per thousand people compared to 85 units per thousand in the United States and blood-borne diseases are much more prevalent (159, 161a). Costly diagnostics and handling regulations, increasingly stringent donor deferral criteria, and a lack of blood donors partly explain this problem (17, 51, 70, 161). However, other issues, including emergent pathogens and natural disasters are of concern (1, 24, 25, 32, 34, 50, 59, 60, 89, 128, 141, 161). Disease transmission and adverse reactions from misstransfusions remain problematic even with best practices in place (30, 103, 129, 133, 161). These and other factors have led to a cost explosion in the industry (105), with the price of blood units increasing significantly in recent years (7, 11, 134).

Recombinant hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (rHBOCs), along with many other naturally occurring Hb-based products, provide an alternative transfusion strategy (46, 100, 124). rHBOCs consist of concentrated solutions of purified acellular human Hb, which has been heterologously expressed in transgenic bacteria, mice, swine, yeast, and other organisms (2, 12, 28, 31, 52, 62, 78, 79, 85, 95–97, 123, 135, 136, 145, 156). They are analogous to non-rHBOCs, which are constructed from human or animal Hb obtained from whole blood. Both types of products can be transfused in place of packed red blood cells to restore impaired oxygen transport and offer the following advantages: (i) universal compatibility; (ii) longer shelf-life; (iii) diminished risk of disease transmission; (iv) enhanced oxygen delivery; (v) improved rheological properties; (vi) improved uniformity in composition; (vii) more reliable availability; and (viii) use by individuals who cannot receive conventional blood transfusions for clinical, geographical, or religious reasons (55, 88, 94, 143, 147). Despite these advantages, significant efforts at developing HBOCs and rHBOCs have not yet resulted in therapeutic licensure in the United States, although HBOC 201 (Hemopure™; OPK Biotech, Boston, MA) is approved for human use in South Africa and Russia (40, 72). The lack of approval of these HBOC products in the United States is primarily due to reports of adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with hypertension (4, 18, 26, 40, 44, 55, 64, 65, 72, 74, 81, 88, 94, 105, 138, 143). In the case of recombinant HBOCs, additional barriers to development include globin denaturation, misfolding, and heme-orientational disorder, issues that arise during expression of recombinant heme proteins (46, 108). There are also significant downstream processing problems, including the removal of large amounts of antigenic Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharides (LPS), protein impurities, and modified hemes and free porphyrin, all of which increase costs (109). Finally, additional formulations may be needed, including polymerization (or encapsulation) to prevent endothelial extravasation and increase particle O2-carrying capacity or PEGylation to enhance stability and inhibit vessel wall penetration (46, 56, 111).

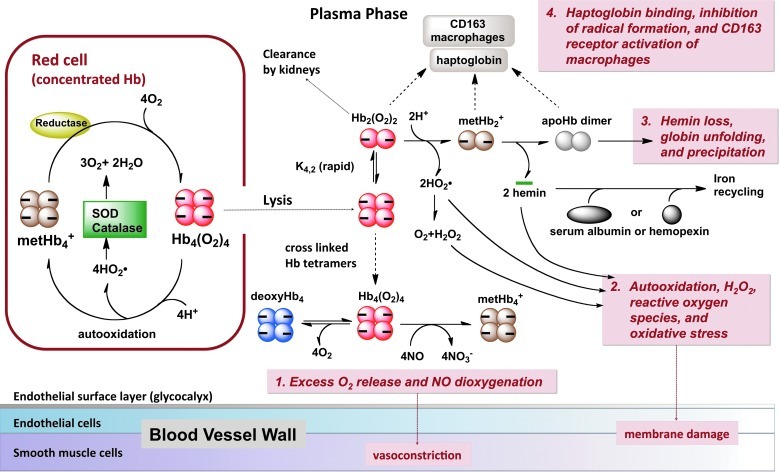

Figure 1 outlines the events that extracellular Hb undergoes in vivo. These include nitric oxide (NO) scavenging, tissue-damaging oxidative reactions, hemin loss, denaturation, aggregation, precipitation, and uptake by macrophages via the CD163 haptoglobin–Hb receptor, internalization, and proteolysis of the globin. The erythrocyte membrane and endogenous reduction systems mitigate or prevent these reactions in intact erythrocytes. Outside the red cells, however, all levels of acellular Hb are associated with some degree of enhanced morbidity and mortality rates (122, 138). Small-to-moderate levels of hemolysis (10–100 μM free Hb) can occur after red blood cell transfusions, chronic inflammatory disorders, myocardial infarction, septic shock, sickle cell crises, and physical injury (19, 67). Ten-fold higher levels of free Hb (200–1000 μM) can occur due to acute hemolytic disorders, hemorrhaging, or trauma (122), and even higher levels of acellular Hb (2000–6000 μM) are generated after HBOC infusion (19, 67). Regardless of dosage, there is a general consensus that toxic reactions associated with acellular Hb are either the direct cause of the pathology or an enhancer of pre-existing clinical conditions.

FIG. 1.

Physiologically relevant reactions involving acellular hemoglobin (Hb) that are possible causes of toxicity. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.

Historical Overview of Recombinant Hb

Experiments with recombinant Hb first began in the 1980s when investigators created transgenic organisms capable of producing high yields of human Hb (75). Transgenic pigs were produced that expressed up to 32 g of human Hb per liter of hemolysate, amounting to 24% of the total Hb content in the erythrocytes (135). Expression of rHb in E. coli and S. cerevisiae was also accomplished with impressive yields (i.e., 2%–10% of the total cellular protein content consists of Hb) (2, 28, 52, 62, 74, 79, 96, 97, 136, 156). Although each system has its own set of advantages and drawbacks, most recent efforts have focused on E. coli production systems.

In the early 1980s, Nagai et al. showed that the unfolded β-subunits from human Hb could be expressed and isolated from inclusion bodies in E. coli. The denatured globin could be refolded and reconstituted with hemin in the presence of native, reduced α-chains to produce functional, tetrameric Hb (47, 90–92). Subsequently, Nagai developed a similar system for obtaining unfolded α-globin and reconstituting it with native β-chains (92, 125, 146). Two years later, Somatogen's and Nagai's groups developed an Hb operon for coexpression of α- and β-chains with the addition of exogenous heme to produce large amounts of intact, soluble tetrameric Hb in E. coli (62, 79, 80). Sligar's group developed a similar Hb operon system to express human adult human Hb A (HbA) (57, 58). The initial expression systems used an extra N-terminal methionine to facilitate bacterial translation of the subunit genes. However, this approach led to heterogeneity due to incomplete processing of the N-terminal Met, and as a result, both groups adopted V1M mutations, for which no cleavage of the N-terminal Met occurs. A few years later, T-J. Shen and C. Ho developed a system in which α- and β-chains containing an extra N-terminal Met were coexpressed with E. coli methionine aminopeptidase to allow complete removal of the initiator amino acid and generation of recombinant Hb identical in a primary structure to native HbA (136, 137). The Somatogen and Nagai groups also developed a fused di-α gene, which was inserted in an operon with a copy of the β-gene to express a tetramer that does not dissociate into α1β1 dimers under normal physiological conditions, even when very dilute (79). The latter genetically crosslinked tetramer was called rHb0.1, with the 0.1 referring to one glycine linker between the two α-polypeptides, and this recombinant protein served as the genetic background for their initial rHBOC products. The first prototype for initial animal and phase I human trials was rHb1.1, which had the V1M mutations for expression in E. coli, the fused di-α-subunits with one glycine linker, and the Hb Presbyterian mutation (N108K) to decrease oxygen affinity to a value similar to that observed for intact human red blood cells (79).

Engineering Principles for rHBOC Products

Early studies showed that transfusing stroma-free, unmodified, extracellular Hb into humans results in renal dysfunction, hypertension, and abdominal pain (87, 94, 126). Subsequent work indicated that free HbA tetramers dissociate into dimers when diluted into plasma. These dimers pass through the kidney glomerular filters, resulting in an initial rapid clearance. Because the dimers are relatively unstable, autooxidation, hemin loss, and precipitation also occur, leading to obstruction of the kidney pores and oxidative stress with attendant renal failure (3, 21, 46, 74, 124). Another problem is that extracellular Hb rapidly scavenges endothelial NO and interferes with vasoregulation. In addition, the oxygen transport behavior of cell-free Hb is substantially different from that of erythrocyte-encapsulated Hb.

To address clearance issues associated with tetramer dissociation into dimers, investigators initially experimented with ways to inhibit Hb dissociation by chemical, physical, or genetic methods, including polymerization, conjugation, encapsulation into vesicles, and fusion of the subunit genes (94). Although polymerization and conjugation with polyethylene glycol polymers (PEGylation) strategies significantly mitigated problems associated with short circulation life spans and renal toxicity, there does not appear to be a consensus in the field as to the ideal HBOC formulation. The most successful strategy for rHBOCs has historically involved the use of a di-α gene with a single glycine linker between the C-terminal end of one α-subunit and the N-terminal end of the other and coexpression with V1M β subunits (79). Initial studies with these genetically crosslinked tetramers suggested that a number of biochemical properties needed to be optimized. These include (i) adjusting oxygen affinity and binding rate constants for efficient O2 transport, (ii) reducing rates of NO dioxygenation (NOD), (iii) increasing resistance to auto-oxidation and hemin loss, and (iv) enhancing globin stability for both high levels of expression during production in E. coli and inhibited denaturation during storage or in blood.

Rational mutagenesis can be used to optimize these properties, although alternative engineering approaches could be used, including directed evolution or random mutagenesis to select or screen for new rHb molecules with more desirable properties. Random mutagenesis is a very powerful approach if little is known about a protein's structure and function. Studies of random substitutions at the 64 (E7), 67 (E10), and 68 (E11) positions have been evaluated in sperm whale myoglobin. In this work, colonies were screened for red color as an indication of globin stability and efficient expression. Interestingly, these studies provided little new information about apomyoglobin stability and hemin affinity and confirmed what had already been established from rational mutagenesis experiments (98, 140). Although significant technical advancements have been made in the area of directed evolution, screening a large library of Hb variants simultaneously for four to five distinct properties in bacteria is not yet technically feasible with current methods. Highly complex expression systems with appropriate selective pressures have not yet been devised, and as a result, essential experiments cannot be performed without labor-intensive protein purification steps. Thus, over the past 20 years, only rational and comparative mutagenesis approaches have generated useful and practical results. However, directed evolution- or library-screening approaches could potentially advance the field more rapidly if an appropriate screening methodology were developed.

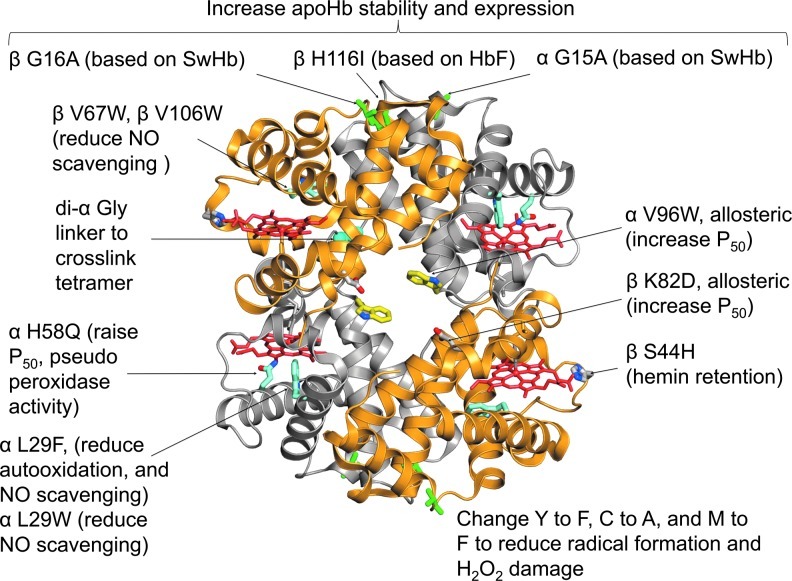

Figure 2 depicts a hypothetical rHBOC prototype that contains 10 mutations designed to optimize several properties. The purpose of each mutation is described briefly in the legend and in the figure. The initial second-generation rHBOC, which was developed by Baxter Hemoglobin Therapeutics (formerly Somatogen) and Olson's group at Rice University, contained the di-α-Gly linker, V1M mutations for expression in E. coli, βV67W and αL29W mutations to reduce NO scavenging ∼30-fold, and the αH58Q mutation to enhance O2 dissociation from α-subunits (33, 35, 99). The genetically crosslinked tetrameric prototype was named rHb3011 and then polymerized and PEGylated to generate rHb2.0 by Baxter Hemoglobin Therapeutics (56, 99, 110, 116). Unfortunately, there were no systematic attempts to determine quantitatively the benefit of the additional polymerization and PEGylation steps compared to the simple genetically crosslinked tetramer with low rates of NOD and moderate O2 affinity. Both PEGylation and polymerization lower the extent of the hypertensive effect of acellular HBOC products by themselves and so do the mutations, but it is not clear if the effects are additive.

FIG. 2.

Structure of human rHb containing mutations designed to optimize specific properties. The structure is a composite of the following rHb protein data bank (PDB) files: 101L [di-α Gly(L29F)/β(WT)], 101M [di-α-Gly(WT)β(V67W)], and 1VWT [α(V96W)/β(WT)]. The remaining mutations were modeled into the composite structure. The mutations shown were selected to: (i) crosslink the tetramer by creating a di-α gene with a single glycine linker (di-αGly); (ii) inhibit the rate of nitric oxide dioxygenation (NOD) ≥20-fold by reducing the capture volume in the distal portion of the heme pocket (αL29F or L29W and βV67W or βV106W); (iii) raise P50 (lower O2 affinity) directly by weakening stabilization of the bound ligand (αH58Q) or allosterically stabilizing the T or low affinity quaternary state of the tetramer (αV96W or βK82D [Hb Providence]); (iv) reduce autooxidation rates (αL29F) and inhibit hemin loss (βS44H); (v) reduce production of reactive ferryl species and protein radicals, enhance pseudoperoxidase activity by the αH58Q mutations, and inhibit protein radical formation by Y to F, C to A, and M to F at key locations;and (vi) enhance apoHb stability by strengthening the α1β1 interface (αG15A, βG16A, and βH116I) as described in the text. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.

Unfortunately, the L29W(B10) mutation, which lowers the rate of the NOD reaction in α-subunits, also decreases the stability of apoHb, reduces expression yields, and increases autooxidation and hemin loss, even though NO scavenging is reduced, and O2 binding is optimized (see Figs. 5 and 6). The similar L28W(B10) mutation in β-subunits creates an even more unstable Hb, which is why this replacement was not used in the second-generation product.

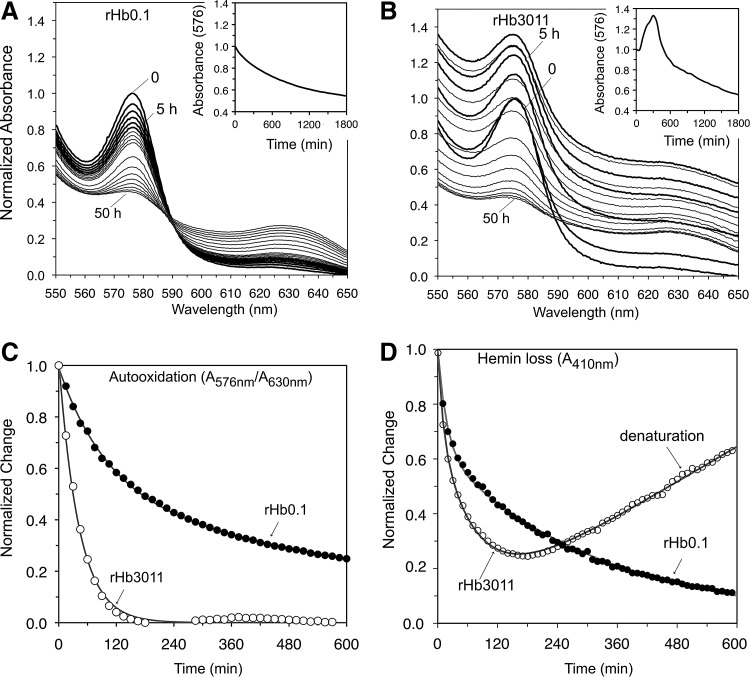

FIG. 5.

Autooxidation, hemin loss, aggregation, and precipitation of rHb3011 at 37°C, pH 7. (A) Spectra of oxy-rHb0.1, bold lines every 1 h; gray lines every 5 h; insets, time courses for A576nm. (B) Same data for oxy-rHb3011. In both (A) and (B) the initial A576nm was normalized to 1.0, and catalase and superoxide dismutase were present at 12 and 6 mmol/mol of heme respectively. (C) Time courses for autooxidation, showing the normalized change of the ratio A576nm/A630nm; (D) time courses for hemin loss measuring the decrease in A410nm as hemin transferred to the H64Y/V68F apoMb reagent. The increase at long times for rHb3011 is due to aggregation of the apoglobin and an increase in turbidity.

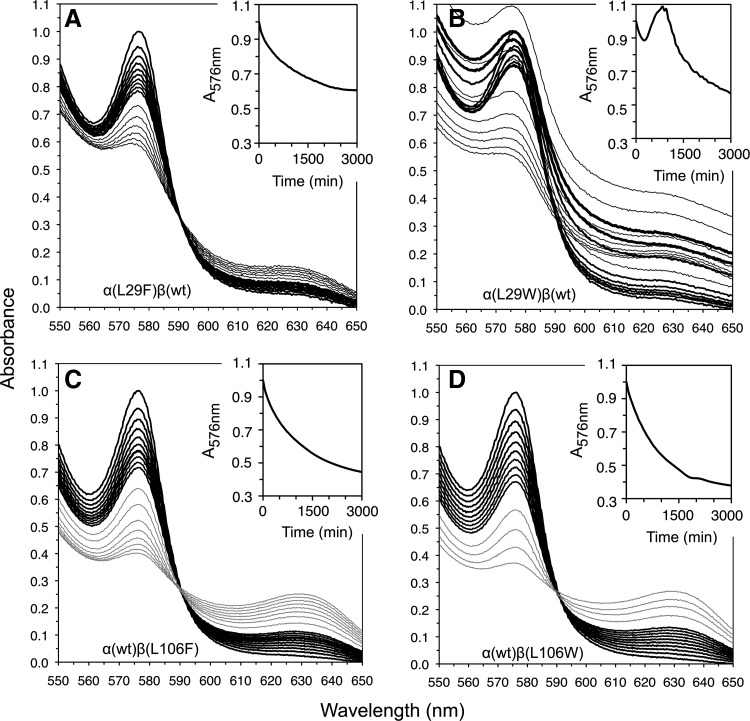

FIG. 6.

Autooxidation and denaturation of αB10 and βG8 mutants in wt/mutant hybrid rHbO2 tetramers at pH 7, 37°C. Spectral changes following autooxidation of (A) α (L29F) β (wt); (B) α (L29W) β (wt); (C) α (wt) β (L106F); and (D) α (wt) β (L106W) recombinant human Hb. The black lines, spectra collected every 1 h for the first 10 h; gray lines, every 5 h afterward; insets, time courses for A576nm. Only half the expected absorbance change at A576nm is observed for α(L29F)β(wt) after 50 h, suggesting very slow autooxidation of the mutated subunit. In all cases, the initial A576nm was normalized to 1.0. Catalase and superoxide dismutase were present at 12 and 6 mmol/mol of heme, respectively.

The other mutations in Figure 2 have not been used in a product. However, we and others have investigated them as potentially useful substitutions that can (i) increase P50 by selectively stabilizing the low-affinity (T) quaternary state by substitutions at allosteric sites [αV96W or βK82D (83, 158)]; (ii) decrease the rate of hemin dissociation from β-subunits [βS44H (160)]; (iii) increase the resistance of apoHb to unfolding [β G16A, β H116I, and α G15A (52)], and (iv) decrease the lifetimes of destructive protein radicals and ferryl species after treatment with H2O2 by changing tyrosines to phenylalanines and vice versa, removing cysteines to prevent thiol radicals and oxidation to cysteic acid, and methionines to phenylalanines to prevent degradation to sulfones and other breakdown products (113, 114). It is not clear how many of these mutations are needed for a safe, effective, and commercially feasible rHBOC.

Controlling O2 Affinity and NOD

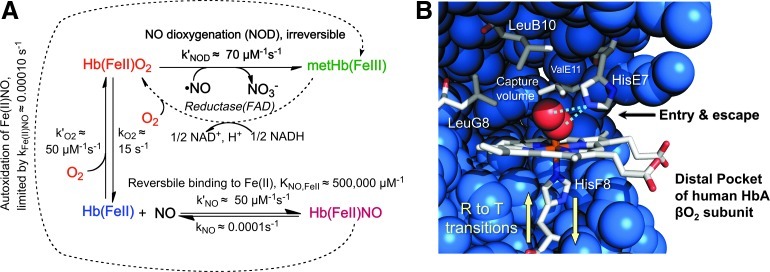

The affinity and rate constants for O2 binding are crucial properties that need to be engineered for rapid uptake and release by Hb in response to changing partial pressures of oxygen in the microcirculation. The optimum parameters for oxygen transport by Hb in human red blood cells appear to be a P50=30–50 μM (20–40 mm Hg) at 37°C and association (k′O2) and dissociation (kO2) rate constants ≥1 μM −1s−1 and ≥2 s−1, respectively (22, 35, 63, 76, 93, 104, 150). The mechanisms that govern O2 binding have been established in detail and used to design recombinant Hb molecules with P50 values that range from ≤0.2 to ≥200 μM, using both allosteric and active site mutations (14, 35, 83). The more difficult challenge has been to inhibit the rate of NO scavenging without markedly altering the rates of O2 uptake and release. The key reactions of NO with reduced Hb are shown in Figure 3A (69, 99). Even if some free NO binds to deoxyHb, its ultimate fate will be irreversible dioxygenation to nitrate if any O2 is present (45). To reduce the rate of NO scavenging, strategies had to be devised to selectively inhibit NOD.

FIG. 3.

O2 binding, NO dioxygenation, and active site of Hb subunits. (A) Rates of reaction of NO and O2 with adult human Hb A (HbA) (35, 45, 99). (B) Structure of the active site of oxygenated human HbA β subunit (PDB 2DN1). The helical positions LeuB10, HisE7, ValE11, HisF8, and LeuG8 correspond to the 29, 58, 87, 62, and 101 sequence positions, respectively, in α subunits and the 28, 63, 67, 92, and 106 positions in β subunits of human HbA. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.

Both the NOD reaction to produce nitrate and bimolecular NO binding to Fe(II) are limited by the rate of entry and capture of the ligand (38, 101). The distal histidine (E7) acts like the thumb of a baseball glove, rotating outward to allow ligand entry, which is then captured in the internal pocket surrounded by Leu(B10), Phe(CD1), Val(E11), and Leu (G8) (Fig. 3B) (13–15, 131). Both NOD and bimolecular ligand binding can be inhibited by filling the back of the pocket with large Phe or Trp replacements at these positions (Fig. 3B) (15, 35, 38, 101), which cause the incoming ligand to reflect back out of the pocket before the His(E7) gate closes. Insertion of large aromatic side chains at the B10 position are much more effective at reducing k′NODin α-subunits than mutations at the E11 and G8 positions, whereas the opposite is true in β-subunits (13, 38). The largest reductions in the rate of NO scavenging in β-subunits have been achieved with Trp replacements at the E11 position (13, 38, 99).

In α-subunits, the bimolecular rates of NO and O2 binding are reduced to almost the same extent as the rates of the NOD reaction by single Trp or Phe mutations at the B10, E11, and G8 positions. However, replacement of His(E7) with Gln in these space-filling mutants allows discrimination between ligand binding and the NOD reaction. The lack of ordered water in the distal pocket of Gln(E7) deoxy-α-subunits (39) allows more rapid bimolecular ligand binding, but hydrogen bonding between Gln(E7) and bound O2 still occurs and acts as a barrier to NO entry and dioxygenation. The hydrogen bond donated by Gln(E7) to bound O2 is weaker than that donated by His(E7), which reduces O2 affinity, increases the rate of O2 release, but, combined with Trp(B10), maintains a low value of k′NOD (Fig. 4B) (35).

FIG. 4.

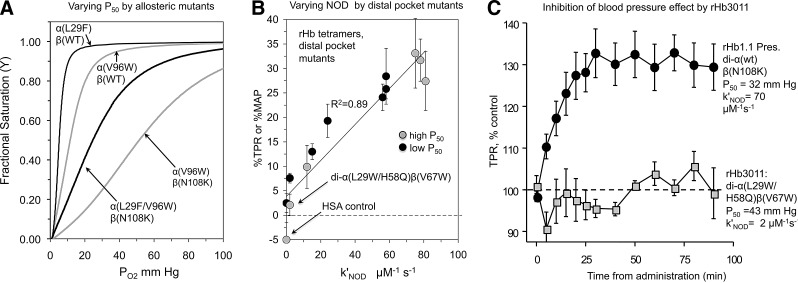

Successful variants for independently varying P50 (83) and NOD rates (99) and for reducing the blood pressure effect in rat model systems by lowering k′NOD (36, 99). rHb1.1 contains the Hb Presbyterian mutation βN108K to maintain a high P50. HSA refers to infusion of human serum albumin instead of an recombinant hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier (rHBOC) (36, 99). (A) Increasing P50 with allosteric mutations (83); (B) Decreasing mean arterial blood pressue (MAP) and/or total peripheral resistance (TPR) by reducing k′NOD, the bimolecular rate constant for NO dioxygenation (99); (C) Eliminating the blood pressure effect by distal pocket mutations (99).

This multiple-mutation strategy was used to construct prototype rHb molecules with both high and low O2 affinity and systematically reduced NOD rates and blood pressure effects when transfused into rats (Fig. 4B) (33, 99). The correlation between k′NOD and changes in mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) or total peripheral resistance (TPR), ΔMAP or ΔTPR in Figure 4B, provides strong, if not unambiguous, evidence that the blood pressure effect caused by acellular Hb is due to NO scavenging. The most successful rHBOC prototype was called rHb3011 [di-α(L29W/H58Q)β(V67W) in Fig. 4B] and has a markedly reduced k′NOD, a high P50, and moderate rates of O2 binding and release (33, 99). Acellular rHb3011 does not cause a rapid increase in TPR (MAP/cardiac output) when infused into rats at a level of ∼0.35 g of rHb per kg of animal, which increased the blood volume by 10% (99), whereas the control, rHb1.1, with a high rate of NOD, causes a ≥30% increase (Fig. 4C). The simplest interpretation of Figure 4C is that the low rate of NOD reduces the toxicity of rHb3011 with respect to hypertension. The rHb3011 molecule has also been shown to reduce or prevent gastrointestinal dysmotility (54), and its genetic background was built into the last Baxter HBOC prototype, rHb2.0, which also showed no hypertensive side effect (56, 84, 110, 116, 142, 155). However, rHb2.0 was later shown to cause complement activation in initial safety trials in humans (40), which, as shown in Figure 5, appears to be due to high rates of auto-oxidation, hemin loss, and/or globin denaturation, properties that were not optimized in the second-generation product, but have been shown to lead to endothelial damage and inflammatory responses (8–10).

Autooxidation, Hemin Loss, and Reactivity with H2O2

Recent work has demonstrated that, in addition to NOD activity, spontaneous and H2O2-induced oxidation of Hb iron atoms to the ferric and ferryl states can lead to diverse pathophysiologies that are thought to be related to hemin loss and destruction, iron-catalyzed redox reactions, and globin denaturation (112, 115). These events may be linked to the adverse events observed after HBOC infusion and must also be addressed in rHBOC prototypes. Baldwin, Alayash, and others have shown that these oxidative processes can damage the endothelial cells of blood vessel walls and the epithelial cells lining intestinal villi after transfusion with simple tetrameric HBOCs (4, 5, 8–10, 20). Thus, in addition to reducing NO scavenging, protein-engineering strategies also need to generate rHbs that are more resistant to oxidation and denaturation than the native globin.

One simple method for screening resistance to auto-oxidation and denaturation is to incubate rHb variants in an air-equilibrated buffer and follow autooxidation and precipitation over a period of days at pH 7 at 37°C. Sterile conditions are required to prevent bacterial growth, and catalase and superoxide dismutase are necessary to prevent acceleration due to H2O2 accumulation. Evaluations of several candidate rHbs are shown in Figure 5. The results show that oxygenated rHb3011 is unstable for long periods of time at 37°C. The absorbance spectra for rHb3011 are suggestive of the formation of soluble aggregates, which then precipitate within 30 h (Fig. 5B and inset). By contrast, rHb0.1 exhibits a slow autooxidation process, with isosbestic points and a two exponential decay curve (Fig. 5A) representing differences between the α- and β-subunits (148, 162). This behavior is similar to that observed for wild-type HbA obtained from donated red blood cells. The samples in Figures 5 and 6 had not been subjected to a final removal of LPS. When LPS levels are lowered to <1 E.U. per ml of concentrated protein (∼1 mM heme), the rates of precipitation after oxidation and hemin loss are slowed, but the relative behavior remains the same, with rHb3011 being very unstable at 37°C (data not shown). Thus, LPS appears to facilitate unfolding of apoglobin, perhaps by either binding to the empty heme pocket or acting as a surfactant (66, 120, 121).

An estimate of the rate of autooxidation for rHb3011 can be obtained by plotting the change in the ratio A576nm/A630nm (∼[HbO2]/[metHb]) as a function of time to compensate for changes in turbidity and precipitation of the sample. As shown in Figure 5C, rHb3011 autooxidizes 5-fold to 20-fold more rapidly than rHb0.1. The instability of the resultant met-rHb3011 is most likely due to rapid hemin loss and unfolding. When we looked at hemin dissociation directly (Fig. 5D), rHb3011 loses its prosthetic group about two-to-four times more rapidly than rHb0.1. The resultant apo-rHb3011 also rapidly denatures, increasing the turbidity of the solution within 1–2 h, as shown by the almost linear slow increases in absorbance at 410 nm (Fig. 5D). These detrimental properties of the TrpE7 and TrpE11 mutations probably account for the unsuccessful initial human safety trials of rHb2.0 that was based on the rHb3011 design. The oxidative stress and inflammation resulting from plasma Hb denaturation seem a likely cause of complement activation, although this conclusion needs further testing (40). Regardless, it is clear that alternative strategies are needed for lowering NO scavenging while retaining low rates of autooxidation, hemin loss, and globin unfolding.

The instability of rHb3011 is due to the presence of Trp29(B10) in α-subunits and Trp67(E11) in β-subunits. Similar rapid rates for the appearance of turbidity and precipitation occur for α(L29W)β(wt), but not α(L29F)β(wt) (Fig. 6A, B), and for α(wt)β(V67W), but not α(wt)β(V67F), rHb (data not shown). In contrast, the α(wt)β(L106W) mutant was resistant to unfolding and precipitation (Fig. 6C, D), and thus Trp106(G8) can be used in β-subunits to slow NO scavenging without compromising stability. One lesson learned from these simple experiments is that NO scavenging can be reduced without compromising stability by using αPhe29, βLeu67, and βTrp106 insertions. Individually, the βV67L and βL106W mutations reduce k′NOD roughly ∼4-fold (data not shown), and in combination, they are expected to achieve a ≥16-fold decrease. The cause for the reduction of capture volume in deoxy-βTrpG8 subunits is the presence of a water molecule in the distal pocket, which is held in place by three hydrogen bonds, including one from the indole N–H atoms (13).

Alayash's group and many others (5, 18, 20, 149) have suggested that the ferryl species and protein radicals produced by the reaction of H2O2 with acellular Hb cause many of the side effects associated with acellular Hb. This same group has shown that administration of haptoglobin can mitigate the oxidative stress caused by acellular Hbs (6, 20, 127). Alternatively, Reeder, Cooper, Wilson, and colleagues have suggested that Hb can be engineered to be less toxic with respect to the generation of long-lived protein radicals by engineering electron transfer pathways that enhance pseudoperoxidase activity by speeding up reduction of ferryl species to more-inert ferric states (112–114). For example, they have shown that α-Tyr42 facilitates reduction of ferryl α-subunits back to the ferric state in the presence of reducing agents found in plasma, including ascorbate, and suggested that engineering more efficient reduction pathways would stabilize acellular Hb (113). Similarly Alayash has also suggested that replacing more reactive amino acids with more inert ones might also prevent Hb damage and radical generation (i.e., C to A, and M to F in Fig. 2)

Increasing Expression Yields with Heme Transporters

A major limitation in the production of recombinant Hb stems from its instability during expression in E. coli. Although recombinant technology allows for expression of large amounts of protein, often the majority of the globin lacks the heme prosthetic group that is required for function and stability (57, 157, 158). Heme synthesis by E. coli is simply too slow to keep up with induced synthesis of recombinant heme proteins from high-copy-number plasmids, and thus a high apo-/holoprotein ratio is observed in the absence of added heme. The availability of heme is the most dominant factor limiting the high-level expression of recombinant Hb in E. coli. Hb expressed without adequate amounts of heme results in both proteolysis and precipitation into inclusion bodies, from which reconstitution of holoHb is inefficient, time consuming, and costly (57, 157).

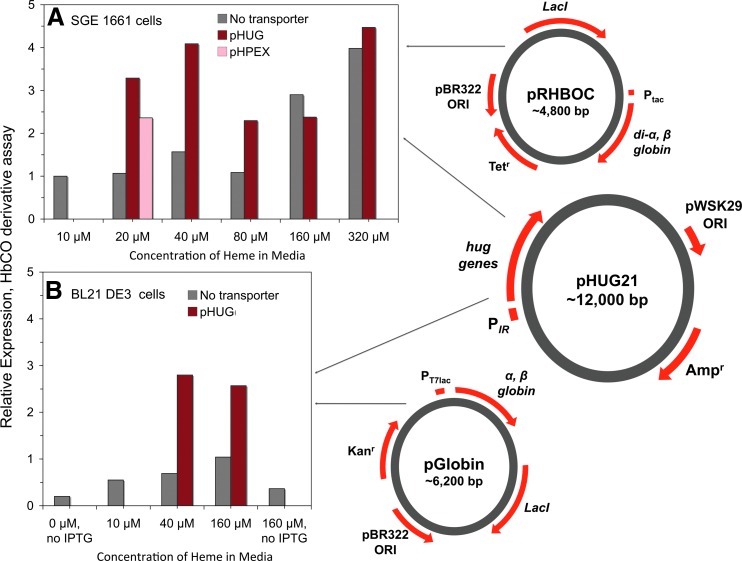

In current rHBOC production protocols, holoHb expression is maximized by adding ∼160–320 μM free hemin to the growing culture after induction of the Hb genes (Fig. 7). Normal E. coli strains do not have an outer membrane heme transporter and cannot use heme as an iron source. Thus, very high levels of exogenous heme are needed for passive diffusion, and only certain strains, presumably with smaller, more porous outer membranes, can be used (primarily based on E. coli JM109 strains). This protocol was developed by Somatogen, Inc., in the early 1990s (80) and is also used by Chien Ho's group for producing recombinant Hb in E. coli (137). Stimulation of endogenous heme synthesis by E. coli can be achieved by the addition of δ-aminolevulonic acid, but this reagent is too expensive to use routinely for large-scale production, and the enhancement of rHb production is not as great as adding high levels of exogenous hemin. However, the addition of large amounts of hemin leads to the generation of degradation products that contaminate the rHb preparations, including metal-free porphyrins that must be removed to prevent photoinduced oxidation of the samples (109).

FIG. 7.

Strategies for co-expressing recombinant hemoglobin and bacterial heme transporter genes. Relative expression of wild type rHb0.1 (di-α Gly/βwt) in Escherichia coli as a function of media heme concentration with and without co-expression of the Plesiomonas shigelloides heme transport system [pHUG(IR)] or with chuA from E.coliO157:H7 [pHPEX(IR)] where IR is the iron regulated promoter. Expression was measured using the CO derivative assay described by Graves et al. (52). The expression levels are relative to that measured for rHb0.1 expression in 10 μM heme with no heme transport co-expression. (A) Expression in the JM109-based E. coli cells developed by Somatogen, SGE 1661 cells using the pRHBOC plasmid with the α and β HbA genes under Ptaccontrol and the pHUG21 plasmid with the hug genes under PIRcontrol. (B) Expression in BL21 DE3 E. coli using the pGlobin plasmid with the α and β genes under PT7lac control and the same pHUG21(IR) plasmid for hug gene expression. The expression levels are normalized to the control in (A), which is our standard system. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.

Attempts have been made to address the heme uptake problem by coexpressing heterologous heme transport systems with the Hb genes, so that less hemin has to be added and uptake is more efficient. We have examined two systems: (i) the pHUG system developed originally by D. Henderson at the University of Texas, Permian Basin, which expresses the complete Plesiomonas shigelloides heme utilization gene (hug) operon (52, 153); and (ii) the pHPEX system, which was developed by C. Varnado and D. Goodwin at Auburn University (151). The latter system coexpresses the apoglobin genes with the chuA outer membrane receptor from pathogenic E. coli O157:H7. Two sample coexpression experiments are shown in Figure 7. In panel A, the E. coli strain SGE1661 (JM109 based) was grown with the rHb vector pRHBOC alone or cotransformed with either the hug vector pHUG21 or the chuA vector pHPEX. In panel B, the E. coli strain BL-21 DE3 was grown with the pET-based rHb vector pGlobin or cotransformed with the pHUG21.

In each case, rHb expression was induced by IPTG addition. The heme transport genes are regulated by the iron-regulated (IR) promoter and induced by iron depletion using the iron chelator ethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetic acid (52, 153). As shown, much more Hb is produced at low (20–40 μM) external heme concentrations when the heme transporters are coexpressed, and the pHUG system is more effective than the pHPEX system. High levels of expression are also seen at larger concentrations of external heme, and, under these conditions, coexpression of the hug genes does not significantly increase the apparent expression levels. However, samples from the high heme incubations contain significant levels of sulfheme and partially denatured holoprotein, which lead to large decreases in final product yields.

Sulfhemoglobin, having a characteristic absorbance peak in the visible spectrum around 620 nm, is a result of the reaction of inorganic sulfides with iron–protoporphyrin IX. The modified heme is likely created as a result of redox chemistry from reactive oxygen species (ROS, i.e., O2•−, H2O2, and Fe(IV)=O) generated in the cells. ROS levels are increased by the presence of high amounts of the highly reactive free hemin. Reports of sulf- and other modified hemes have also been described for the expression of recombinant myoglobin variants with green to blue colors (49, 77). Although heating steps or redox recycling can be used to remove protein with modified heme, these procedures often lead to lower protein yields. In our hands, optimal holoHb production requires coexpression with the hug genes at low exogenous heme levels (∼20–40 μM).

Expression of Hb in E. coli cell lines that are less porous (i.e., BL-21) than JM109 cells requires the presence of an outer membrane heme receptor to obtain measureable amounts of soluble holoHb, regardless of the concentration of heme added (Fig. 7B). This need for heme transport has also been shown for the expression of high levels of other heme proteins in BL-21 cells (117, 151). Expression of Hb with a heme transporter and low concentrations of heme result in an increase in holoprotein production, and at the same time limits the fraction of modified heme complexes, which decrease the yield of functional and stable human Hb.

Increasing Expression Yields with α-Hb Stabilizing Protein

α-Hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP) is a conserved molecular chaperone that is thought to facilitate HbA expression in mammalian erythroid precursors (48, 68). Work characterizing this protein suggests that it facilitates HbA α-subunit structure acquisition and diminishes α-subunit reactivity with ROS by stabilizing a hemichrome-folding intermediate (42, 43, 163). These findings indicate that coexpressing AHSP with rHb in E. coli might result in greater production yields of rHb. Vasseur-Godbillon et al. (152) investigated this hypothesis by coexpressing AHSP with α-subunits. Although β-subunits were not included in this study, it was found that AHSP enhanced α-subunit expression yields dramatically. More recently, Faggiano et al. (41) coexpressed AHSP with both α- and β-subunits to produce a self-polymerizing bovine rHb in E. coli. In contrast to the work of Vasseur-Godbillon et al. (152) on the expression of α-subunits alone, Faggiano et al. (41) found that AHSP impedes rHb production when expressed with the α- and β-subunits in equimolar amounts. We have independently conducted coexpression assays in our laboratory using rHb in pET and AHSP in pBAD expression vectors to vary the levels of AHSP with respect to the α- and β-subunits. Our preliminary results also suggest that high [AHSP] may inhibit rHb formation, but low catalytic levels of AHSP may facilitate production or holo-rHb (86). However, much more work is needed to verify these observations.

Enhancing apoHb Stability

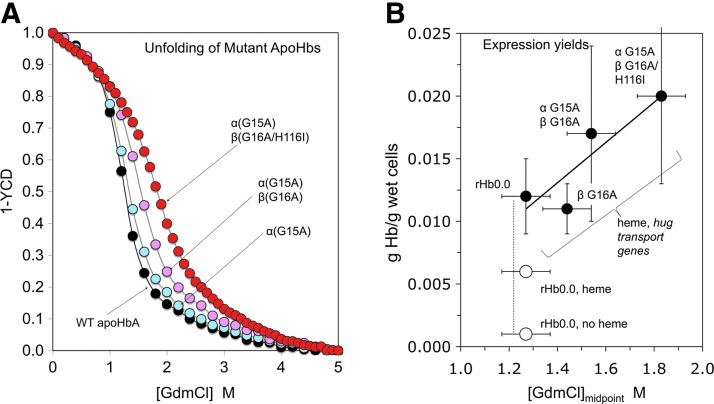

In 2000, we discovered that apoMb and apoHb stability varies widely among different mammalian species and that it is a major limiting factor in the production of intact holoproteins in E. coli (52, 132, 140). Sperm whale myoglobin, sperm whale Hb, and human fetal Hb are all more stable than human Hb A (52). By comparing the primary amino acid sequences of these proteins, Graves et al. (52) identified three mutations that markedly increase the resistance of apoHbA to GdmCl-induced unfolding (Fig. 8A). These mutations include αG15A, βG16A, and βH116I. Although βH116I is located directly in the α1β1 interface within HbA, the other mutations are solvent-exposed residues of the A-helices very near the AB loop at the edges of the interface. Therefore, they most likely exert their effects by increasing the stability of the A helix secondary structure.

FIG. 8.

Correlation between apoglobin stability and expression yield of holoHb. (A) GdmCl-induced unfolding curves of wild-type human rHb and three mutants containing replacements based on comparisons between sperm whale, adult human, and fetal human Hb sequences (52). There is a clear progressive increase in stability, with the [GdmCl]midpoint increasing from ∼1.2 to 1.9 M. (B) Correlations between the grams of holohemoglobin isolated per gram of cell paste with GdmCl midpoint concentrations of apoHb unfolding curves (52). Closed circles, co-expression of rHbs with P. shigelloides hug genes and in the presence of 60 μM external heme. Open circles, yields without expression of hug genes±added external heme. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.

These mutations were incorporated into rHb expression vectors, and the proteins produced using these constructs were purified and characterized by Graves et al. (52). As shown Figure 8A, the stabilizing effects of these mutants are additive, and each mutation progressively increases rHb resistance to chemical denaturation by GdmCl. The expression yields of these rHbs were also found to be variable, with the incorporation of each mutation resulting in predictable increases in rHb expression levels. These results are shown in Figure 8B, which is a plot of expression level in vivo against GdmCl-induced denaturation midpoint measured in vitro [data taken from Graves et al. (52)]. These gains appear to be additive to the enhancement obtained with the use of the P. shigeloides heme transport (hug) genes discussed in the previous section; however, the standard errors in the small growth assay are very large and much more systematic work in bioreactors is needed (Fig. 8B).

Bioreactor Protocol Optimization

Previous work using small scale assays have shown that Hb production can be increased by ten-fold in E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with a single plasmid containing human Hb genes and P. shigelloides heme transport genes, versus the strain containing only the Hb genes (153). As described in Figure 8, Graves et al. (52) found that modifying the Hb genes to generate a more stable form of Hb also increased Hb produced in E. coli. Recently, Smith et al. (139) described a protocol to produce Hb in a bioreactor, which combined both approaches. Their procedure included the following important features: (i) expression of the human Hb variant with the stability mutations on the same plasmid as the P. shigelloides heme transport genes (52); (ii) the use of a mass flow equation for glucose addition (73) and close monitoring of glucose levels to optimize cell growth and plasmid retention; (iii) addition of phosphate later in the run to better enable the transport and metabolism of glucose (118); and (iv) induction of the culture during the mid log phase of growth and the addition of a heme/base feed at the time of induction that is controlled by pH.

Using this procedure, the cultures reached an average OD600 of 281 and a dry cell weight of 84 g/L, with the OD600 and dry cell weight increasing threefold and twofold, respectively, over what was seen at induction. In addition, the cultures produced 6.6 g/L of Hb in clarified lysates or ∼0.08 g of Hb/g of dry weight cells. This production level is similar to that shown in Figure 8 for the triple stability mutant in small scale 50 ml cultures without purification [∼0.06 g/g dry wt, assuming that the dry weight of cells is 0.3 that of the wet weight of paste (16)]. Both results are highly encouraging and suggest that the production of recombinant Hb in E. coli may be an economically viable method of obtaining therapeutic Hb, as was argued previously by Baxter Hemoglobin Therapeutics (109, 158).

Cost of rHb Production

One of the major issues with rHBOCs is production cost. In the United States, one unit of whole blood can vary from 405 to 550 ml and is collected from adult donors whose Hb concentration can range from 12.5 to 18.0 g/dL (119). A single unit of blood can therefore contain 50.6–99.0 g of Hb. In 2011, the United States Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services fixed reimbursement prices at $202.83/unit for whole blood and $154.32/unit for packed red blood cells (www.aabb.org/programs/reimbursementinitiatives/Pages/12hoppsrule.aspx). These prices do not include costs that arise subsequent to purchase from blood centers (e.g., those associated with blood administration, storage, transport, disposal, and adverse event treatment), and blood centers may of course charge more or less than the fixed reimbursable costs. However, these reimbursable prices suggest that the cost of Hb on a per unit mass basis is roughly $2/g to $4/g. As a comparison, current rHb expression methods using E. coli can generate 0.38–6.6 g of rHb per liter of clarified bacterial lysate (80, 109, 139, 158). Based on nonbulk costs of growth media, hemin, antibiotic, glucose, and expression inducer and assuming a 60% purification recovery we estimate that it is possible to produce rHb at a cost of approximately $11/g. However, if we include costs of equipment investment and maintenance, utilities, labor, waste disposal, purification, downstream processing, and other operating expenses, the cost increases to ≥$200/g. However, with further optimization and economies of large-scale production, rHb could become comparably priced or only moderately more expensive than whole blood and packed red blood cells as a source of Hb.

Endotoxin Removal

Although expression of rHb in bacterial systems has the potential for large-scale applications, endotoxin levels are increased due to antigenic LPS present in the bacterial cell wall that bind to Hb (66, 120). In addition, Levin and coworkers have provided evidence that Hb binding enhances the inflammatory responses caused by LPS (66, 121). The standard purification procedure for rHb decreases endotoxin levels by several orders of magnitude. However, additional steps are needed to lower endotoxin levels for safe use in humans.

In the early 1990s, Somatogen, Inc. conducted a variety of initial safety trials with healthy human volunteers with their initial rHb1.1 (Optro) product. Many of the subjects developed pyrogenic responses and gastrointestinal problems, most of which were the result of bacterial endotoxin and protein contamination (109). These results led to the development of a “flash” heating step for the CO complex followed by a Q Sepharose FF column, both of which remove large amounts of weakly bound LPS, free porphyrin, and other contaminants and decrease the endotoxin levels to ≤2 EU/g (109). Polymyxin B agarose, diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) cellulose, or ɛ-poly-L-lysine cellulose can be used to safely and efficiently remove any remaining LPS as long as breakdown of the column matrix does not occur (61). These techniques led to the use of the first (rHb1.1) and second (rHb2.0) products in humans where, as described in previous sections, the observed side effects were much less severe and appeared to be due to NO scavenging (Fig. 4) and protein instability (Fig. 5). The latter are intrinsic properties of the Hb itself and not bacterial contaminants, although it is always difficult to exclude the possibility of contamination.

Although current LPS reduction techniques may be satisfactory, most pharmacopeias specify an upper limit of 5 EU per kg of body mass per hour for intravenous therapeutics (107). Infusion of therapeutic levels of rHBOCs in a trauma care context will require hundreds of grams of protein. Thus, LPS-mitigation requirements for this amount of a rapidly infused rHBOC are more stringent than most other therapeutic proteins, which are used in milligram-level quantities. Thus, although expression in E. coli is required for pilot-scale experiments and screening of small to medium sized libraries of prototype rHBOCs, it may eventually be more practical to use previously developed heterologous expression in mammalian systems for large scale manufacturing of a rHBOC product (135).

Future Prospects

The use of extracellular Hb as a blood substitute is probably the most economically and scientifically feasible way to produce an oxygen carrier when donated blood is not available. Recombinant technology allows the use of rational protein engineering strategies to mitigate or eliminate toxic effects caused by the presence of acellular Hb in the circulation (i.e., the problems shown in Fig. 1). Genetic crosslinking of α subunits prevents dissociation into dimers. Detailed mechanisms of O2 binding to and NOD by Hb provide a blueprint for addressing efficacy and interference with vasoregulation. Similar protein engineering strategies can be used to inhibit autooxidation, hemin loss, and globin unfolding, all of which can cause oxidative stress and inflammation. Future work should be aimed at reducing production costs and identifying the specific ensemble of suitable rHb mutations.

Abbreviations Used

- AHSP

α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein

- Apo

heme-lacking

- Hb

hemoglobin

- HbA

adult human hemoglobin A

- HBOC

hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier

- heme

ferroprotoporphyrin IX

- hemin

ferriprotoporphyrin IX

- IR

iron regulated

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- met

ferric oxidation state

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOD

nitric oxide dioxygenation

- rHb

recombinant hemoglobin

- rHBOC

recombinant hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TPR

total peripheral resistance

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Betsy Poindexter for helpful discussions regarding the costs associated with blood utilization in the United States. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grants HL47020 (J.S.O.), GM35649 (J.S.O.), HL110900(JSO), HL079992 (D.P.H.), University of Texas Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation Funds (Equipment Funds, UT Permian Basin) (D.P.H.), and Robert A. Welch Foundation Grant C-0612 (I.B., J.S.O., T.L.M.). T.L.M. received support from the Institute of Biosciences and Bioengineering NIH Biotechnology Predoctoral Training Grant (GM008362) and C.L.V. received funding from the Baylor College of Medicine Hematology Training Program (T32 DK60445).

References

- 1.Abolghasemi H. Radfar MH. Tabatabaee M. Hosseini-Divkolayee NS. Burkle FM., Jr. Revisiting blood transfusion preparedness: experience from the Bam earthquake response. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:391–394. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00006117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi K. Konitzer P. Lai CH. Kim J. Surrey S. Oxygen binding and other physical properties of human hemoglobin made in yeast. Protein Eng. 1992;5:807–810. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alayash AI. Hemoglobin-based blood substitutes: oxygen carriers, pressor agents, or oxidants? Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:545–549. doi: 10.1038/9849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alayash AI. Oxygen therapeutics: can we tame haemoglobin? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:152–159. doi: 10.1038/nrd1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alayash AI. Setbacks in blood substitutes research and development: a biochemical perspective. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alayash AI. Haptoglobin: Old protein with new functions. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin M. Fergusson D. Aziz A. Wilson K. Coyle D. Hebert P. The cost of allogeneic red blood cells—a systematic review. Transfus Med. 2003;13:275–285. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2003.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin AL. Blood substitutes and redox responses in the microcirculation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:1019–1030. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin AL. Wiley EB. Alayash AI. Comparison of effects of two hemoglobin-based O(2) carriers on intestinal integrity and microvascular leakage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1292–H1301. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00221.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldwin AL. Wiley EB. Alayash AI. Differential effects of sodium selenite in reducing tissue damage caused by three hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:893–903. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00615.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basha J. Dewitt R. Cable D. Jones G. Transfusions and their costs: managing patients needs and hospitals economics. Internet J Emerg Intensive Care Med. 2006;9 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behringer RR. Ryan TM. Reilly MP. Asakura T. Palmiter RD. Brinster RL. Townes TM. Synthesis of functional human hemoglobin in transgenic mice. Science. 1989;245:971–973. doi: 10.1126/science.2772649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birukou I. Maillett DH. Birukova A. Olson JS. Modulating distal cavities in the alpha and beta subunits of human HbA reveals the primary ligand migration pathway. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7361–7374. doi: 10.1021/bi200923k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birukou I. Schweers RL. Olson JS. Distal histidine stabilizes bound O2 and acts as a gate for ligand entry in both subunits of adult human hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8840–8854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birukou I. Soman J. Olson JS. Blocking the gate to ligand entry in human hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10515–10529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bratbak G. Dundas I. Bacterial dry matter content and biomass estimations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:755–757. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.755-757.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks JP. Reengineering transfusion and cellular therapy processes hospitalwide: ensuring the safe utilization of blood products. Transfusion. 2005;45:159S–171S. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buehler PW. Alayash AI. All hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers are not created equally. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1378–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buehler PW. D'Agnillo F. Schaer DJ. Hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers: from mechanisms of toxicity and clearance to rational drug design. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buehler PW. Karnaukhova E. Gelderman MP. Alayash AI. Blood aging, safety, and transfusion: capturing the “radical” menace. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1713–1728. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunn HF. Esham WT. Bull RW. The renal handling of hemoglobin. I. Glomerular filtration. J Exp Med. 1969;129:909–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.5.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bunn HF. Forget BG. Hemoglobin, Molecular, Genetic and Clinical Aspects. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch MP. Kleinman SH. Nemo GJ. Current and emerging infectious risks of blood transfusions. JAMA. 2003;289:959–962. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamberland ME. Emerging infectious agents: do they pose a risk to the safety of transfused blood and blood products? Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:797–805. doi: 10.1086/338787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamberland ME. Alter HJ. Busch MP. Nemo G. Ricketts M. Emerging infectious disease issues in blood safety. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:552–553. doi: 10.3201/eid0707.010731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang TM. Future generations of red blood cell substitutes. J Intern Med. 2003;253:527–535. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cinat ME. Wallace WC. Nastanski F. West J. Sloan S. Ocariz J. Wilson SE. Improved survival following massive transfusion in patients who have undergone trauma. Arch Surg. 1999;134:964–968. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.9.964. discussion 968–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coghlan D. Jones G. Denton KA. Wilson MT. Chan B. Harris R. Woodrow JR. Ogden JE. Structural and functional characterisation of recombinant human haemoglobin A expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:931–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Como JJ. Dutton RP. Scalea TM. Edelman BB. Hess JR. Blood transfusion rates in the care of acute trauma. Transfusion. 2004;44:809–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cyranoski D. Tainted transfusion leaves Japan scrambling for safer blood tests. Nat Med. 2004;10:217. doi: 10.1038/nm0304-217a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dieryck W. Pagnier J. Poyart C. Marden MC. Gruber V. Bournat P. Baudino S. Merot B. Human haemoglobin from transgenic tobacco. Nature. 1997;386:29–30. doi: 10.1038/386029b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodd RY. Leiby DA. Emerging infectious threats to the blood supply. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:191–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty DH. Doyle MP. Curry SR. Vali RJ. Fattor TJ. Olson JS. Lemon DD. Rate of reaction with nitric oxide determines the hypertensive effect of cell-free hemoglobin. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:672–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong J. Olano JP. McBride JW. Walker DH. Emerging pathogens: challenges and successes of molecular diagnostics. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:185–197. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dou Y. Maillett DH. Eich RF. Olson JS. Myoglobin as a model system for designing heme protein based blood substitutes. Biophys Chem. 2002;98:127–148. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyle MP. Armstrong AM. Brucker EA. Fattor TJ. Lemon DD. Design of second generation recombinant hemoglobin: minimizing nitric oxide scavenging and vasoactivity while maintaining efficacy. Artif Cells Blood Sub Immobil Biotech. 2001;29:100. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eder AF. Chambers LA. Noninfectious complications of blood transfusion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:708–718. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-708-NCOBT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eich RF. Li T. Lemon DD. Doherty DH. Curry SR. Aitken JF. Mathews AJ. Johnson KA. Smith RD. Phillips GN., Jr. Olson JS. Mechanism of NO-induced oxidation of myoglobin and hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6976–6983. doi: 10.1021/bi960442g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esquerra RM. Lopez-Pena I. Tipgunlakant P. Birukou I. Nguyen RL. Soman J. Olson JS. Kliger DS. Goldbeck RA. Kinetic spectroscopy of heme hydration and ligand binding in myoglobin and isolated hemoglobin chains: an optical window into heme pocket water dynamics. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:10270–10278. doi: 10.1039/c003606b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Estep T. Bucci E. Farmer M. Greenburg G. Harrington J. Kim HW. Klein H. Mitchell P. Nemo G. Olsen K. Palmer A. Valeri CR. Winslow R. Basic science focus on blood substitutes: a summary of the NHLBI Division of Blood Diseases and Resources Working Group Workshop, March 1, 2006. Transfusion. 2008;48:776–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faggiano S. Bruno S. Ronda L. Pizzonia P. Pioselli B. Mozzarelli A. Modulation of expression and polymerization of hemoglobin polytaur, a potential blood substitute. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;505:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng L. Gell DA. Zhou S. Gu L. Kong Y. Li J. Hu M. Yan N. Lee C. Rich AM. Armstrong RS. Lay PA. Gow AJ. Weiss MJ. Mackay JP. Shi Y. Molecular mechanism of AHSP-mediated stabilization of alpha-hemoglobin. Cell. 2004;119:629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng L. Zhou S. Gu L. Gell DA. Mackay JP. Weiss MJ. Gow AJ. Shi Y. Structure of oxidized alpha-haemoglobin bound to AHSP reveals a protective mechanism for haem. Nature. 2005;435:697–701. doi: 10.1038/nature03609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferguson E. Prowse C. Townsend E. Spence A. Hilten JA. Lowe K. Acceptability of blood and blood substitutes. J Intern Med. 2008;263:244–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foley EW. Rice University; Houston, TX: 2006. Physiologically relevant reactions of myoglobin and hemoglobin with NO [Ph.D. Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fronticelli C. Koehler RC. Design of recombinant hemoglobins for use in transfusion fluids. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.12.010. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fronticelli C. O'Donnell JK. Brinigar WS. Recombinant human hemoglobin: expression and refolding of beta-globin from Escherichia coli. J Protein Chem. 1991;10:495–501. doi: 10.1007/BF01025477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gell D. Kong Y. Eaton SA. Weiss MJ. Mackay JP. Biophysical characterization of the alpha-globin binding protein alpha-hemoglobin stabilizing protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40602–40609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibson QH. Regan R. Olson JS. Carver TE. Dixon B. Pohajdak B. Sharma PK. Vinogradov SN. Kinetics of ligand binding to Pseudoterranova decipiens and Ascaris suum hemoglobins and to Leu-29→Tyr sperm whale myoglobin mutant. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16993–16998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glynn SA. Busch MP. Schreiber GB. Murphy EL. Wright DJ. Tu Y. Kleinman SH. Effect of a national disaster on blood supply and safety: the September 11 experience. JAMA. 2003;289:2246–2253. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.17.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goodnough LT. Brecher ME. Kanter MH. AuBuchon JP. Transfusion medicine. First of two parts—blood transfusion. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:438–447. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graves PE. Henderson DP. Horstman MJ. Solomon BJ. Olson JS. Enhancing stability and expression of recombinant human hemoglobin in E. coli: progress in the development of a recombinant HBOC source. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1471–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greinacher A. Fendrich K. Alpen U. Hoffmann W. Impact of demographic changes on the blood supply: Mecklenburg-West Pomerania as a model region for Europe. Transfusion. 2007;47:395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartman JC. Argoudelis G. Doherty D. Lemon D. Gorczynski R. Reduced nitric oxide reactivity of a new recombinant human hemoglobin attenuates gastric dysmotility. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;363:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henkel-Honke T. Oleck M. Artificial oxygen carriers: a current review. AANA J. 2007;75:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hermann J. Corso C. Messmer KF. Resuscitation with recombinant hemoglobin rHb2.0 in a rodent model of hemorrhagic shock. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:273–280. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270756.11669.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hernan RA. Hui HL. Andracki ME. Noble RW. Sligar SG. Walder JA. Walder RY. Human hemoglobin expression in Escherichia coli: importance of optimal codon usage. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8619–8628. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernan RA. Sligar SG. Tetrameric hemoglobin expressed in Escherichia coli. Evidence of heterogeneous subunit assembly. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26257–26264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hess J. Thomas M. Blood use in war and disaster: lessons from the past century. Transfusion. 2003;43:1622–1633. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hess JR. Blood use in war and disaster: The U.S. experience. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2005;13:74–81. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hirayama C. Sakata M. Chromatographic removal of endotoxin from protein solutions by polymer particles. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;781:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoffman SJ. Looker DL. Roehrich JM. Cozart PE. Durfee SL. Tedesco JL. Stetler GL. Expression of fully functional tetrameric human hemoglobin in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8521–8525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang H. Olsen KW. Thermal stabilities of hemoglobins crosslinked with different length reagents. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1994;22:719–724. doi: 10.3109/10731199409117903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Intaglietta M. Editorial: Blood Substitutes Better Than Blood. Transfus Altern Tranfus Med. 2008;9:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jia Y. Ramasamy S. Wood F. Alayash AI. Rifkind JM. Cross-linking with O-raffinose lowers oxygen affinity and stabilizes haemoglobin in a non-cooperative T-state conformation. Biochem J. 2004;384:367–375. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaca W. Roth RI. Levin J. Hemoglobin, a newly recognized lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein that enhances LPS biological activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25078–25084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kato GJ. Taylor JG. Pleiotropic effects of intravascular haemolysis on vascular homeostasis. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:690–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kihm AJ. Kong Y. Hong W. Russell JE. Rouda S. Adachi K. Simon MC. Blobel GA. Weiss MJ. An abundant erythroid protein that stabilizes free alpha-haemoglobin. Nature. 2002;417:758–763. doi: 10.1038/nature00803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim-Shapiro DB. Schechter AN. Gladwin MT. Unraveling the reactions of nitric oxide, nitrite, and hemoglobin in physiology and therapeutics. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:697–705. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000204350.44226.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klein H. Will blood transfusion ever be safe enough? JAMA. 2000;284:238–240. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klein H. How safe is blood, really? Adv Transfus Safety. 2010;38:1–104. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kluger R. Red cell substitutes from hemoglobin—do we start all over again? Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Korz DJ. Rinas U. Hellmuth K. Sanders EA. Deckwer WD. Simple fed-batch technique for high cell density cultivation of Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 1995;39:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(94)00143-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kresie L. Artificial blood: an update on current red cell and platelet substitutes. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2001;14:158–161. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2001.11927754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar R. Recombinant hemoglobins as blood substitutes: a biotechnology perspective. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;208:150–158. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lemon DD. Boland EJ. Nair PK. Olson JS. Hellums JD. Effects of physiological factors on oxygen transport in an in vitro capillary system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;222:37–44. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9510-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lloyd E. Mauk AG. Formation of sulphmyoglobin during expression of horse heart myoglobin in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1994;340:281–286. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Logan JS. Martin MJ. Transgenic swine as a recombinant production system for human hemoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1994;231:435–445. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)31029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Looker D. Abbott-Brown D. Cozart P. Durfee S. Hoffman S. Mathews AJ. Miller-Roehrich J. Shoemaker S. Trimble S. Fermi G, et al. A human recombinant haemoglobin designed for use as a blood substitute. Nature. 1992;356:258–260. doi: 10.1038/356258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Looker D. Mathews AJ. Neway JO. Stetler GL. Expression of recombinant human hemoglobin in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1994;231:364–374. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)31025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lowe K. Blood substitutes: from chemistry to clinic. J Mat Chem. 2006;16:4189–4196. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luban NL. Transfusion safety: where are we today? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1054:325–341. doi: 10.1196/annals.1345.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maillett DH. Simplaceanu V. Shen TJ. Ho NT. Olson JS. Ho C. Interfacial and distal-heme pocket mutations exhibit additive effects on the structure and function of hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10551–10563. doi: 10.1021/bi800816v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malhotra AK. Kelly ME. Miller PR. Hartman JC. Fabian TC. Proctor KG. Resuscitation with a novel hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier in a Swine model of uncontrolled perioperative hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2003;54:915–924. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000061000.74343.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Manjula BN. Kumar R. Sun DP. Ho NT. Ho C. Rao JM. Malavalli A. Acharya AS. Correct assembly of human normal adult hemoglobin when expressed in transgenic swine: chemical, conformational and functional equivalence with the human-derived protein. Protein Eng. 1998;11:583–588. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.7.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mollan TL. Rice University; Houston TX: 2011. The role of the alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein in human hemoglobin assembly [Ph.D. Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moore E. Blood substitutes: the future is now. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01704-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moore E. Emerging role of hemoglobin solutions in trauma care. Transfus Altern Tranfus Med. 2005;6:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mujeeb SA. Jaffery SH. Emergency blood transfusion services after the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:22–24. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.036848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nagai K. Perutz MF. Poyart C. Oxygen binding properties of human mutant hemoglobins synthesized in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7252–7255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nagai K. Thogersen HC. Generation of beta-globin by sequence-specific proteolysis of a hybrid protein produced in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1984;309:810–812. doi: 10.1038/309810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagai K. Thogersen HC. Synthesis and sequence-specific proteolysis of hybrid proteins produced in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1987;153:461–481. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nair PK. Huang NS. Hellums JD. Olson JS. A simple model for prediction of oxygen transport rates by flowing blood in large capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1990;39:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(90)90070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ness PM. Cushing MM. Oxygen therapeutics: pursuit of an alternative to the donor red blood cell. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:734–741. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-734-OTPOAA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O'Donnell JK. Martin MJ. Logan JS. Kumar R. Production of human hemoglobin in transgenic swine: an approach to a blood substitute. Cancer Detect Prev. 1993;17:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ogden JE. Coghlan D. Jones G. Denton KA. Harris R. Chan B. Woodrow J. Wilson MT. Expression and assembly of functional human hemoglobin in S. cerevisiae. Biomater Artif Cells Immobilization Biotechnol. 1992;20:473–475. doi: 10.3109/10731199209119671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ogden JE. Harris R. Wilson MT. Production of recombinant human hemoglobin A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1994;231:374–390. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)31026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Olson JS. Eich RF. Smith LP. Warren JJ. Knowles BC. Protein engineering strategies for designing more stable hemoglobin-based blood substitutes. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1997;25:227–241. doi: 10.3109/10731199709118912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Olson JS. Foley EW. Rogge C. Tsai AL. Doyle MP. Lemon DD. No scavenging and the hypertensive effect of hemoglobin-based blood substitutes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Olson JS. Maillett DH. Designing Recombinant Hemoglobin for Use as a Blood Substitute. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Olson JS. Soman J. Phillips GN., Jr. Ligand pathways in myoglobin: a review of Trp cavity mutations. Iubmb Life. 2007;59:552–562. doi: 10.1080/15216540701230495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.This reference has been deleted

- 103.Otsubo H. Yamaguchi K. Current risks in blood transfusion in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61:427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Page TC. Light WR. McKay CB. Hellums JD. Oxygen transport by erythrocyte/hemoglobin solution mixtures in an in vitro capillary as a model of hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier performance. Microvasc Res. 1998;55:54–64. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1997.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pape A. Habler O. Alternatives to allogeneic blood transfusions. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21:221–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pape A. Stein P. Horn O. Habler O. Clinical evidence of blood transfusion effectiveness. Blood Transfus. 2009;7:250–258. doi: 10.2450/2008.0072-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Petsch D. Anspach FB. Endotoxin removal from protein solutions. J Biotechnol. 2000;76:97–119. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Piro MC. Militello V. Leone M. Gryczynski Z. Smith SV. Brinigar WS. Cupane A. Friedman FK. Fronticelli C. Heme pocket disorder in myoglobin: reversal by acid-induced soft refolding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11841–11850. doi: 10.1021/bi010652f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Plomer J. Ryland J. Mathews A. Traylor D. Milne E. Durfee S, et al. Purification of hemoglobins U.S. Patent 5,840,851 (PCT publication number WO 96/15151) 1997.

- 110.Raat NJ. Effects of recombinant-hemoglobin solutions rHb2.0 and rHb1.1 on blood pressure, intestinal blood flow, and gut oxygenation in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146:304–305. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Raat NJH. Liu J-F. Doyle MP. Burhop KE. Klein J. Ince C. Effects of recombinant-hemoglobin solutions rHb2.0 and rHb1.1 on blood pressure, intestinal blood flow, and gut oxygenation in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;145:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Reeder BJ. The redox activity of hemoglobins: from physiologic functions to pathologic mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1087–1123. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Reeder BJ. Grey M. Silaghi-Dumitrescu RL. Svistunenko DA. Bulow L. Cooper CE. Wilson MT. Tyrosine residues as redox cofactors in human hemoglobin: implications for engineering nontoxic blood substitutes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30780–30787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804709200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Reeder BJ. Svistunenko DA. Cooper CE. Wilson MT. Engineering tyrosine-based electron flow pathways in proteins: the case of aplysia myoglobin. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7741–7749. doi: 10.1021/ja211745g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reeder BJ. Wilson MT. Hemoglobin and myoglobin associated oxidative stress: from molecular mechanisms to disease States. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2741–2751. doi: 10.2174/092986705774463021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Resta TC. Walker BR. Eichinger MR. Doyle MP. Rate of NO scavenging alters effects of recombinant hemoglobin solutions on pulmonary vasoreactivity. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1327–1336. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00175.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Richard-Fogal CL. Frawley ER. Feissner RE. Kranz RG. Heme concentration dependence and metalloporphyrin inhibition of the system I and II cytochrome c assembly pathways. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:455–463. doi: 10.1128/JB.01388-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rinas U. Hellmuth K. Kang R. Seeger A. Schlieker H. Entry of Escherichia coli into stationary phase is indicated by endogenous and exogenous accumulation of nucleobases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4147–4151. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4147-4151.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roback JD. Combs MR. Grossman BJ. Hillyer CD. AABB Technical Manual; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Roth RI. Hemoglobin enhances the binding of bacterial endotoxin to human endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:258–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Roth RI. Kaca W. Levin J. Hemoglobin: a newly recognized binding protein for bacterial endotoxins (LPS) Prog Clin Biol Res. 1994;388:161–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rother RP. Bell L. Hillmen P. Gladwin MT. The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin. JAMA. 2005;293:1653–1662. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ryan TM. Townes TM. Reilly MP. Asakura T. Palmiter RD. Brinster RL. Behringer RR. Human sickle hemoglobin in transgenic mice. Science. 1990;247:566–568. doi: 10.1126/science.2154033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sanders KE. Ackers G. Sligar S. Engineering and design of blood substitutes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:534–540. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sanna MT. Razynska A. Karavitis M. Koley AP. Friedman FK. Russu IM. Brinigar WS. Fronticelli C. Assembly of human hemoglobin. Studies with Escherichia coli-expressed alpha-globin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3478–3486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Savitsky JP. Doczi J. Black J. Arnold JD. A clinical safety trial of stroma-free hemoglobin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;23:73–80. doi: 10.1002/cpt197823173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Schaer DJ. Alayash AI. Clearance and control mechanisms of hemoglobin from cradle to grave. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:181–184. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schmidt PJ. Blood and disaster—supply and demand. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:617–620. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200202213460813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]