Abstract

Background. Little is known about Tibetan medicine (TM), in Western industrialized countries. Objectives. To provide a systematic review of the clinical studies on TM available in the West. Data Sources. Seven literature databases, published literature lists, citation tracking, and contacts to experts and institutions. Study Eligibility Criteria. Studies in English, German, French, or Spanish presenting clinical trial results. Participants. All patients of the included studies. Interventions. Tibetan medicine treatment. Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods. Included studies were described quantitatively; their quality was assessed with the DIMDI HTA checklist; for RCTs the Jadad score was used. Results. 40 studies from 39 publications were included. They were very heterogeneous regarding study type and size, treated conditions, treatments, measured outcomes, and quality. Limitations. No Russian, Tibetan, or Chinese publications were included. Possible publication bias. Conclusions. The number of clinical trials on TM available in the West is small; methods and results are heterogeneous. Implications of Key Findings. Higher quality larger trials are needed, as is a general overview of traditional usage to inform future clinical trials. Systematic Review Registration Number. None.

1. Background

Traditional Tibetan medicine (TM), sometimes called “Lamaist” or “Buddhist” medicine, has developed in 1200 years into a unique medical system [1–3]. In TM, disease is understood as an imbalance of the three “Nyes-pa” (principles) consisting of one or two elements: “rLung” (air, wind), “mKhris-pa” (fire), and “Bad kann” (earth and water) [4]. Buddhist philosophy as well as shamanic origins of Tibetan culture form a background of cosmological, mind-body, and spiritual dimensions [1–3]. Treatment may consist of medicines (usually preparations of plants [5], seldom minerals or animals), physical treatments (e.g., massage, baths), life and diet regulation, or spiritual techniques [4]. Standardization of the originally individualized medicines, separation from the underlying philosophies, and discontinuation of some techniques (e.g., Tibetan dental medicine, cauterization) have led to derivative forms of TM [6]. We will use the term “Tibetan medicine” for the traditional TM (with its individual life style advice, diet, physical, and spiritual means) as well as larger or smaller subsets or varieties of it, down to single formulas.

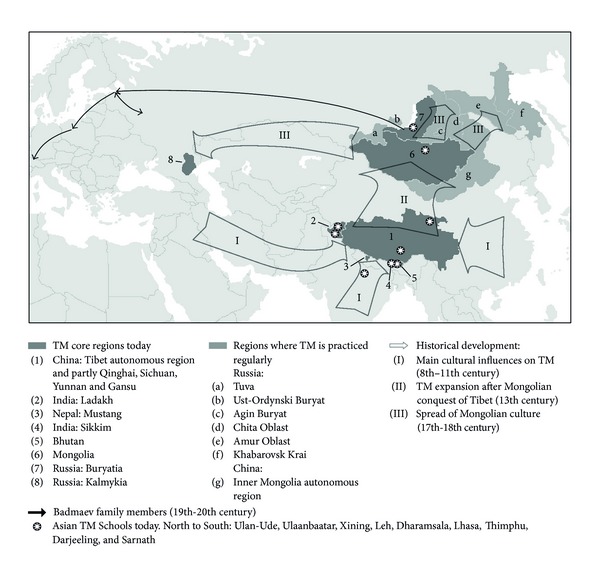

Besides the regions of the historical Tibet, very similar medical traditions are practised since the Mongolian conquest of Tibet in the 13th century in Mongolia, adjacent Siberia, and in the Russian province Kalmykia (Figure 1) [7]. Especially with traditional Mongolian medicine, TM has a substantial similarity. TM use in Western industrialized countries (the “West”) originates in a line of descendants of a Buryat physician migrating westward in the 19th century (Figure 1) [8, 9]. Still, there is little awareness of TM in the general Western public. Following the rising interest in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and complementary or alternative medicine (CAM) in general, more demand from Western countries can be expected in the future. The amount of available research in the West is small. A Medline search up to December 31, 2010, for example, for “Tibetan medicine” returned 371 hits, 0.0183 times the number for “traditional Chinese medicine.” The existing literature indicates a palliative, possibly curative potential, especially for chronic diseases [10], but studies on its multimodal individualized approach are scarce and systematic reviews exist only for one TM product [11–15]. Therefore, we attempted to present in this paper a systematic overview of clinical research currently available in the West on Tibetan medicine, and aim to provide details on methods and study quality. Some preliminary data can be found in [16].

Figure 1.

Tibetan medicine in geography and history. Map based on [7, 8, 17–22].

2. Methods

A preliminary list of 15 literature databases was tested using the search terms “Tibetan medicine,” “Himalaya medicine,” “Tibetan herbal,” and “Lamaistic medicine.” The database list had been compiled from recommendations by experts, by Ovid [23], and by Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) [24]. Those returning the most hits were used for the literature search, together with databases that were recommended by experts or appeared relevant in their characterization on the websites of DIMDI or the Charité library [25]. We finally searched seven databases up to publication date December 31, 2010: ABIM (accessed via Rijksuniversiteit Groningen), AMED (DIMDI), CAMbase (cambase), CCmed (DIMDI), Cochrane Collaborative Library (OVID), Embase (OVID), and Medline (PubMed). The search term “(Tibet OR Himalaya OR Mongolia OR Buddhist) AND (herbal OR medicine) AND study” was adapted as necessary to database language and syntax. Similar searches were used on the medical information services of DIMDI [24] and ZB MED [26] and by adding “AND clinical study” on Google scholar [27]. The published literature lists [28, 29] were screened. We also contacted European experts, research departments of TM medical faculties (Mentsekhang) in Lhasa and Dharamsala, and European centres for TM [30–32]. All identified literature was further screened for relevant citations. Duplicate references were eliminated throughout the process; of multiple publications of a study the most recent one was included. Included papers had to be written in English, German, French, or Spanish and had to present clinical trial results on a clinical outcome. No further restrictions were applied.

One of the authors (K. P. Reuter) used a predefined form to extract descriptive study data into MS Access 2003 and MS Excel 2003 [33, 34] data bases, including bibliographic data, and study parameters such as type, methods (including diagnostics, randomization, and blinding), and patient numbers. Furthermore, data regarding treated diseases, interventions, outcomes, and types of outcome measures (clinical symptoms, tests, and laboratory parameters) were extracted. If no primary outcome was defined, the first outcome mentioned in the title or the abstract was extracted, unclear cases were discussed with another author (C. M. Witt) until consensus was reached.

Methodological quality of the studies was determined with a DIMDI checklist (Table 1) that is used to evaluate studies for in-/exclusion in health technology assessments (HTA) in Germany [35]. The checklist has up to 31 items sorted into 7 categories and was used on a descriptive basis. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were further evaluated with the Jadad score [36, 37]. Descriptive statistics were calculated using MS Access 2003 and MS Excel 2003 [33, 34].

Table 1.

DIMDI HTA checklist items.

| Item* | Item no. (label)** |

|---|---|

| (A) Selection of participants | Participants |

| (1) Were the criteria for in-/exclusion defined sufficiently and clearly? | A1 (in-/exclusion) |

| (2) Were the criteria for in-/exclusion defined before intervention? | A2 (predefined) |

| (3) Was the health status recorded in a valid and reliable way? | A3 (health status) |

| (4) Were the diagnostic criteria of the disease described? | A4 (diagnostic criteria) |

| (5) Were the studied/exposed patients representative for the majority of the exposed population or the “standard users” of the intervention? | A5 (representativity) |

|

| |

| (B) Allocation and study participation | Allocation |

| (1) Were the exposed/cases and nonexposed/controls from the same base population? | B1 (basic population) |

| (2) Were intervention/exposed and control/nonexposed groups comparable at baseline? | B2 (comparable) |

| (3) Was allocation randomized, with a standardized procedure? | B3 (randomization) |

| (4) Was randomization blinded? | B4 (blinded randomization) |

| (5) Were known/possible confounders considered at baseline? | B5 (confounders) |

|

| |

| (C) Intervention/exposition | Intervention |

| (1) Were intervention or exposition recorded in a valid, reliable, and similar way? | C1 (recording) |

| (2) Apart from intervention, were intervention and control groups treated similarly? | C2 (similar treatment) |

| (3) In case of other treatments, were they recorded in a valid and reliable way? | C3 (other treatments) |

| (4) For RCTs: were placebos used for the control group? | C4 (placebo use) |

| (5) For RCTs: was the way of placebo administration documented? | C5 (placebo documented) |

|

| |

| (D) Study administration | Administration |

| (1) Are there indications for “overmatching”? | D1 (overmatching) |

| (2) In multicentre studies: were the diagnostic and therapeutic methods and the outcome recording in the centres identical? | D2 (multicentre) |

| (3) Was if assured that participants did not crossover between intervention and control group? | D3 (no crossover) |

|

| |

| (E) Outcome recording | Outcome |

| (1) Were patient-centred outcome parameters used? | E1 (patient-centred) |

| (2) Were the outcomes recorded in a valid and reliable way? | E2 (recording) |

| (3) Was outcome recording blinded? | E3 (blinded outcomes) |

| (4) For case series: was the distribution of prognostic factors recorded sufficiently? | E4 (prognostic factors) |

|

| |

| (F) Drop-outs | Drop-outs |

| (1) Was the response rate in intervention/control group sufficient, or, for cohort studies, could a sufficient part of the cohort be tracked for the full study duration? | F1 (evaluable number) |

| (2) Were the reasons for the dropouts of participants stated? | F2 (reasons) |

| (3) Were the outcomes of dropouts described and included in the analysis? | F3 (outcomes) |

| (4) If differences were found: were they significant? | F4 (significance) |

| (5) If differences were found: were they relevant? | F5 (relevance) |

|

| |

| (G) Statistical analysis | Statistics |

| (1) Were the described analytic methods correct and the information sufficient for a flawless analysis? | G1 (correct) |

| (2) Were confidence intervals given for means and for significance tests? | G2 (CIs given) |

| (3) Were the results presented in graphical form, and were the underlying values stated? | G3 (graphics) |

3. Results

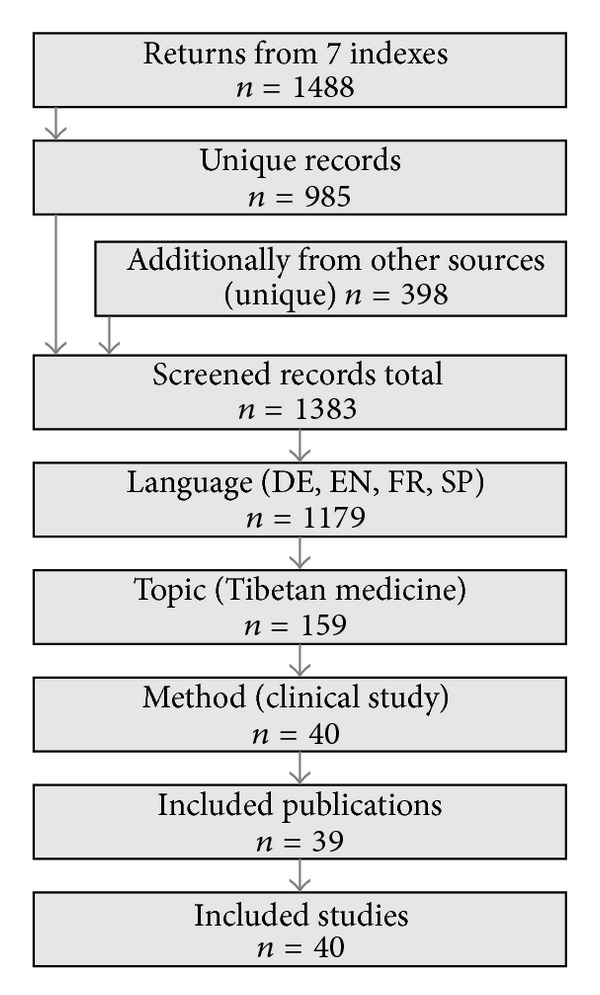

From 1383 screened records, we identified 40 studies reported in 39 publications (one contains 2 studies [38]), see Figure 2. An additional search without the terms “herbal,” “Buddhist,” and “Mongolian” did not result in fewer relevant publications. Thirty-five of the publications were journal articles, two were book chapters, and one is treated in this paper as a single Internet publication, although different findings had been published in several online media reports [39]. Only 18 publications were found by the initial data base searches. Most of the others were indeed indexed, as a reverse search (for already known publications) revealed. Written in English were 53.8% (n = 21) of the publications, the other 46.2% (18) were in German. Most publications came from Poland and Switzerland (30.8% or n = 12 each, all on products of Padma AG). The Asian studies were from India (15.4%, n = 6) or China (5.1%, n = 2). The earliest publication appeared in 1970. Since 1990 every 5 years about 3 new RCTs were published and, less evenly distributed, most of the observational studies (total n = 14). The 5 nonrandomized controlled trials were published between 1986 and 1991, and the 6 case studies or case series in 1998 or later (Table 2). The setting of 7 studies (17.5%) was multicentred [40–46]. Four studies (10.0%) were retrospective [40, 45, 47, 48].

Figure 2.

The literature search. References from indexing services were collected first, then other sources were added.

Table 2.

Included studies.

| Study Type* Country |

Disease (diagnostic system)** | Participants (mean age), drop-outs*** | Duration of intervention or study kind, dose of intervention**** |

(1) Main outcome (2) Other outcomes |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aschoff et al. 1997 OS Germany |

Migraine (BM) | I: 22; D: 0 | 6 months (and longer?) Byu-Dmar 13 jewel pill, 1 U/d |

(1) Severity of attacks reduced by 82% (2) Frequency of attacks unchanged; less use of analgesics in most participants |

Very brief documentation; only subjective outcomes |

|

| |||||

|

Bommeli et al. 2001 rCS (MC) Switzerland |

Various (78% patients w/arteriosclerosis) (BM, TM) | I: 147; D: 18 | From few days to 13.5 years P28, varying doses (~50% of patients 3 × 2 U/d) |

(1) Improvement of complaints in % of patients: peripheral artery occlusive disease in 94%, coronary heart disease in 92%, chronic venous insufficiency in 91%, arthrosis in 80% | Patients from 15 physicians, no demographics, no monotherapy, success not clearly attributable to P28 |

|

| |||||

|

Brunner-La Roccaet al. 2005 RCT (5) Switzerland |

Mild hypercholesterolaemia (BM) | I: 30; C: 30; D: 0 | 4 weeks + 15 d followup I: P28, 3 × 2 U/d C: potato starch |

(1) Total cholesterol unchanged (2) Other blood lipids unchanged |

Participants not typical patients |

|

| |||||

|

Brzosko et al. 1991 CT (4 arms) Poland |

Chronic juvenile arthritis (BM) | I1: 12 (11 years); I2: 7; C1: 10 (healthy); C2: 10 (in remission) | I1: 6 weeks; I2: 4 weeks I1: P28, 2–4 U/d I2: Thymus extract, 1 suppositorium/day |

(1) Joint pain and swelling (Ritchie Index): improved in 75%–83% of P28 patients, in 86% of thymus extract patients (2) Improvement (compared to healthy control) of sedimentation rate, IgG, IgM, seromucoid, CD8-Lymphocytes, CD4/CD8-quotient |

Control is no standard therapy; comparison with healthy probands; immunological parameters not very relevant for contemporary diagnostics |

|

| |||||

|

Brzosko and Jankowski 1992 OS (MC) Poland |

Hepatitis B (BM) | I: 178 including 52 children | 2 years (intervention), 10 years (study) I: P28, 3 × 2 U/d |

(1) “Biochemical markers” (not specified) improved in ~90% (2) Improvements in T lymphocytes (CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD4/CD8) in 90%, hepatocellular virus eliminated in 15%, improvements in immunohistochemistry (HBe-Ak increase in 70%), and clinical findings (in 90%) |

Very brief description of patients and outcomes; no statement about other therapies |

|

| |||||

| Changbar 1998 CS India |

Chronic aplastic anaemia (BM, TM) | I: 1 man (63); D: 0 | 15 months Rinchen yusnying 25 special, 1 on alternating days; Zhiru, 2× on alternating days; Gur gum 8 special, 4 × /d; Se ‘bru kun bde, 3× /d; A gar 8, 4 × /d; dietary recommendations |

(1) Haemoglobin (increase from 3.1 to 10.4 mg/dL) (2) Clinical improvement, reduction of comedication |

|

|

| |||||

|

Cohen et al. 2004 RCT (2) USA |

Mental symptoms accompanying lymphomas (BM) | I: 19; C: 19; D: 9 | 7 weeks + 3 months follow-up 7 weekly sessions of guided yoga (Tsa lung trul khor yoga) |

(1) Sleep disorder improved (2) Despair, anxiety, depression, fatigue not significant, patient's appraisal positive |

Many outcomes in small population increased probability of significant results caused by random variations; high drop-out rate; low compliance |

|

| |||||

| Feldhaus 2004 CS Switzerland |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM, unspecified CAM) | I: 1 woman (61); D: 0 | 1 year P28, 3 × 2 U/d; intestinal cleansing (intestinal hydrotherapy and microbacterial treatment), chelation therapy, oxygenation therapy, orthomolecular treatment, IV treatment with ribonucleic acid |

(1) General condition much improved after 8 months (2) Walking distance improved (<100 m to >2000 m) |

No attribution of effect to TM possible |

|

| |||||

| Feldhaus 2006 CS Switzerland |

Chronic constipation of tetraplegic patients (BM, unspecified CAM) | I: 3; D: 0 | 1–3 months I: PL, 1 × 1-2 U/d; intestinal cleansing (intestinal hydrotherapy and micro bacterial treatment), chelation therapy, other CAM |

(1) Constipation cured in all cases | No attribution of effect to TM possible |

|

| |||||

|

Flück and Bubb 1970 OS (MC) Switzerland |

Chronic constipation (BM) | I: 285 (256 outpatients, 29 inpatients) | “Several” weeks PL, 1 × 1 U/d |

(1) Symptoms improved in 82% (2) Unwanted effects in 6.3% |

Insufficient description of population, inclusion criteria, and diagnostics |

|

| |||||

| Füllemann 2006 OS Switzerland |

Chronic dental pulpitis (BM) | I: 53; D: 4 | 15 days P28, 2 × 2 U/d |

(1) Pain-free within 1 month in 55% (2) Extraction or root canal treatment not necessary in 82% |

Comparison with expectation from experience; 4 drop-outs because of incompliance might have caused false positive result |

|

| |||||

|

Gladysz et al. 1993 OS Poland |

Hepatitis B (BM) | I: 34 | 12 months P28, 3 × 2 U/d |

(1) Serological and liver function parameters improved in 76.5%, liver biopsy improved in 55.9% (2) Other parameters (GGT, GPT, bilirubin, and albumin) unchanged |

Authors claim elimination potential for HBeAg and HBV-DNA similar to interferon standard therapy; unwanted effects not stated |

|

| |||||

| Günsche 2005 CS Switzerland |

Bipolar Disorder (BM) | I: 1 woman (44); D: 0 | 11 months P28, 3 × 2 U/d for 6 weeks, then 3 × 1/d |

(1) and (2) Daytime sleepiness, concentration difficulties, and apathy much improved within 6 weeks, cured after 11 months | Only subjective outcomes |

|

| |||||

| Hürlimann 1979/1 RCT (3) Switzerland |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM) | I: 13; C: 11; D: 0 | 12 weeks I: P28, 3 × 2 U/d C: Placebo |

(1) Pain free walking distance improved by 54% (2) Other symptoms improved in 69%, no change in plethysmography |

Good study design, homogenous groups, very brief presentation of results, valid results |

|

| |||||

| Hürlimann 1979/2 OS Switzerland |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM) | I: 10; D: 0 | Duration not stated P28, 3 × 2 U/d. |

(1) Rest pain improved in 70% | Very brief presentation, duration not stated |

|

| |||||

|

Jankowski et al. 1986 OS Poland |

Recurrent respiratory tract infections (BM) | I: 61 (2 years); D: 0 | 8 weeks P28, 3 × 1 U/d or 3 × 0.5 U/d depending on age, 4 weeks P28—2 weeks pause—2 weeks P28 |

(1) Frequency and intensity of infections reduced in 80% (2) Immunoglobulins and B cells unchanged, T cells normalized, phagocytic activity of leucocytes increased, appetite increased |

Immunological analysis did not include all participants |

|

| |||||

|

Jankowski et al. 1991 CT Poland |

Recurrent respiratory tract infections (BM) | I: 19; C: 10 (healthy); (3 years); D: 0 | 8 weeks P28, 3 × 1 U/d, 4 weeks P28—2 weeks pause—2 weeks P28 |

(1) Bactericide index (“spontaneous bactericidal activity”) improved in 84% | Effect not clearly attributable because of healthy controls; tested bacteria not typical for disease; unusual outcome parameter |

|

| |||||

|

Jankowski et al. 1992 OS Poland |

Recurrent respiratory tract infections (BM) | I: 305 (4 years) | 10 weeks P28, 3 × 1 U P28 or 3 × 0.5 U depending on age |

(1) Frequency and intensity of infections reduced in 72% (2) Increase in CD2+, CD4+ lymphocytes, and CD4/CD8 quotient |

Possibly republished data from earlier studies; immunological results from 48 participants only (randomized?) |

|

| |||||

|

Korwin-Piotrowskaet al. 1992 RCT (2) Poland |

Multiple Sclerosis (BM) | I: 50; C: 50; D: 0 | 12 months I: P28, 3 × 2 U/d C: Placebo, symptomatic treatment |

(1) Clinical course (relapse frequency or progression) improved in 44% (2) Evoked potentials: visual improved in 33%, acoustic unchanged |

Other treatment in placebo group |

|

| |||||

|

Leeman et al. 2001 OS USA |

Breast cancer (BM, TM) | I: 11; DI: 2 | 1 year 2–4 herbal preparations, 2–6×/d; diet, lifestyle regulation, prayer; every 3–4 months adjustment of prescription |

(1) No unwanted effects grade III or IV (2) 1 patient's tumor regressed, 2 were stable for >12 months, 6 progressed |

No peer-reviewed publication; no statements about drop-out's outcomes (possibly disease progress) |

|

| |||||

| Li 2001 OS (MC) Lhasa Prefecture, China |

Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis (BM, TM) | I: 86 | Max. 8 weeks, follow-up of 24 patients after 5 months TM, max. 8 weeks |

(1) Helicobacter test not changed (2) Clinical parameters improved in 76.3%–100% (depending on category), symptom intensity improved |

Therapy according to Tibetan diagnostics in 9 “medication groups”; selection of followup group not stated |

|

| |||||

| Mansfeld 1988 CT Switzerland |

Recurrent respiratory tract infections (BM) | I: 218; C: 205; (11 years); D: 3 | 6 weeks, then observation for 6–12 months I: P28, 3 × 1 U/d, biomedicine when needed, mountain air cure C: biomedicine when needed, mountain air cure |

(1) Frequency and severity of infections tended to improve (not significant) (2) Immunoglobulines and inflammation parameters not significant |

Parents assessed infection severity; other therapies might have masked P28 effect |

|

| |||||

|

Mehlsen et al. 1995 RCT (5) Denmark |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease | I: 20; C: 20; D: 4 | 4 months I: P28, 2 × 2 U/d C: gelatine |

(1) Max. walking distance improved (2) Pain-free walking distance improved, no change in blood pressure and blood pressure ratio ankle/upper arm |

Excellent study design |

|

| |||||

|

Miller et al. 2009 RCT (5) (MC) Lhasa Prefecture, China |

Post-partum haemorrhage (BM, TM) | I: 480; C: 487; D: 7 | Single dose I: Zhi Byed 11, 3 U, and placebo C: Misoprostol, 600 μg, and placebo |

(1) Misoprostol superior to Zhi Byed 11 for: Hemorrhage, maternal death, need for uterotonics (2) No significant difference for mean and median blood loss |

|

|

| |||||

|

Namdul et al. 2001 RCT (1) (MC) India |

Type 2 Diabetes (BM, TM) | I: 100; C: 100; D: 88 (64 after 12 weeks) | 24 weeks I: Kyura-6, Aru-18, Yung-4, and Sugmel-19, daily + life style regulation + diet according to American Diabetes Association C: life style regulation + diet as above |

(1) Fasting blood glucose reduced (2) Postprandial blood glucose and HbA1c reduced, weight, blood pressure, and blood lipids unchanged |

Intervention group more ill despite randomization; values of intervention group taken as baseline; high drop-out rate without further analyses |

|

| |||||

| Neshar 2000 OS India |

Diabetes mellitus (BM, TM) | I: 82; D: 0 (study of patient files) | Min. 6 months Yung-4, Kyuru-6, Chinni-Aru-18, and Sugmel-10, daily + lifestyle and diet regulation |

(1) Blood glucose improved in 70%, stabilized in 100% (2) Improvements in subjective symptoms (92%), and need for biomedicine in 68% |

Regarding general improvement discrimination between TM alone or with additional biomedicine: it is not clear whether biomedicine was given at baseline or became necessary during study; most data refer to a subpopulation of 24 that is not described: selection bias? |

|

| |||||

| Neshar 2007 OS India (MC) |

Cancer (BM, TM) | I: 647; D: 340 | Varying duration Traditional TM (not further specified) |

(1) General health state much improved (2) Improvements in progression, infections, pain, side effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy |

Selection of patients not representative, high drop-out rate |

|

| |||||

| Pauwvliet et al. 1997 OS Netherlands |

Rheumatic disorders (BM, TM) | I: 35; D: 7 | 6 months Traditional TM (not further specified) |

(1) Severity of disease improved (2) Improvements in pain, number of diseased parts general well-being, and mental complaints |

High drop-out rate, 4 of them because of aggravation; prepublication without laboratory data |

|

| |||||

|

Prusek et al. 1987 CT (6 arms) (MC) Poland |

Recurrent respiratory tract infections (BM) | I: 30; C1: 23; C2: 10; C3: 29; C4: 25; C5: 20; (4 years); D: 0 | 11 months I: P28, 3 × 1 U/d for 1 month C1: levamisole, 3 mg/kg: for 2 × 3 d C2: thymus factorx, 1 mg/kg for 3 weeks C3: bacterial lysate, 3.5 mg/d for 3 × 10 d C4: climate cure for 6 weeks C5: healthy probands |

(1) Frequency and severity of infections improved in 57% (less than controls) (2) Immunoglobulines not changed, T cells improved |

Comparability of groups unclear (allocation by clinical indication); statistical evaluation not sufficient |

|

| |||||

| Rüttgers 2004 CS Switzerland |

Chronic venous insufficiency (BM) | I: 1; D: 0 | 3 months and follow-up P28, 3 × 1 U/d and biomedical standard (no primarily angiological) therapy |

(1) Inflammation improved (2) Oedema and pain improved; remission for >6 months; healing faster under P28 |

|

|

| |||||

| Ryan 1997 RCT (3) India |

Arthritis (BM, TM) | I: 15; C: 15; D: 2 | 3 months I: traditional TM (not further specified) C: biomedical treatment |

(1) Motility of extremities improved, in 86% of the matched pairs the TM patient better than respective control | Inclusion by Tibetan diagnosis; no further details to matched pairs; only two pairs of arthritis patients |

|

| |||||

|

Sallon et al. 1998 RCT (4) Israel |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM) | I: 37; C: 35; D: 13 | 6 months I: P28, 2 × 2 U/d C: potato starch |

(1) Ankle-brachial-index unchanged (2) Improved: pressure decrease, ischaemia time, and patient's assessment |

|

|

| |||||

|

Sallon et al. 2002 RCT (4) Israel |

Chronic constipation (BM) | I: 42; C: 38; D: 19 | 12 weeks I: PL, 2 × 2 U/d, C: potato starch |

(1) Improved intestinal passage (2) Improved abdominal pain (physician's assessment) and everyday activity (patient's assessment) |

Comprehensive study documentation |

|

| |||||

|

Samochowiec et al. 1987 RCT (4) Poland |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM) | I: 55; C: 45 | 4 months I: P28, 2 × 2 U/d C: lactose |

(1) Improved max. walking distance (2) Upper arm blood pressure unchanged, improved: total blood lipids, β-lipoproteins, thrombocyte aggregation threshold |

No patient demographics; comparison only to baseline, not between groups |

|

| |||||

|

Sangmo et al. 2007 RCT (2) India |

Hepatitis B (BM, TM) | I: 24; C: 25; D: 1 | 6 months I: Special TM, (not further described) C: Traditional TM |

(1) No differences between groups (2) Both groups tended to improvements in liver function and improved clinically |

Special TM group more ill at baseline; almost no appraisal of results; possibly overtesting; very comprehensive documentation also of Tibetan diagnostics |

|

| |||||

| Schleicher 1990 OS Germany |

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (BM) | I: 15; D: 5 | 6 months P28, 3 × 3 U/d |

(1) Total T cells stabilized (2) Stabilized: suppressor-cytotoxic cells, helper-inducer cells, and lymphocytes; unchanged: B cells and killer cells; increase in granulocytes and phagocytosis |

No patient-centred parameters; prognostically most relevant CD4 cell count and viral load not documented |

|

| |||||

|

Schrader et al. 1985 RCT (4) Switzerland |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM) | I: 27; C: 26; D: 10 | 4 months I: P28, 3 × 2 U/d C: lactose |

(1) Improved max. walking distance (2) Improved pain-free walking distance |

|

|

| |||||

|

Smulski and Wojcicki 1994 RCT (5) Poland |

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (BM, TM) | I: 50; C: 50; D: 7 | 4 months I: P28, 2 × 2 U/d C: lactose |

(1) Max. walking distance improved (2) Patient's assessment more positive, improved total blood lipids, triglycerides, low density lipoproteins |

Comparison of groups only for walking distance |

|

| |||||

|

Split et al. 1998 RCT (2) Poland |

Apoplexy (BM) | I: 60; C: 60 | 14 days I: P28, 3 × 2 U/d + biomedical standard therapy C: biomedical standard therapy |

(1) Better general status (Karnofsky functional efficiency scale, KFES) (2) Better T cells, B cells, and clinical progress |

Age not stated, no blinding, no placebo, comparison only understandable for KFES, therapy effect not discernible from placebo effect |

|

| |||||

|

Wojcicki et al. 1986 CT Poland |

Coronary heart disease, angina pectoris (BM) | I: 50 | 6 weeks Placebo, 2 weeks—P28, 2 × 2 U/d, 2 weeks—placebo, 2 weeks |

(1) Nitroglycerine need reduced (2) Improvement of exercise capacity, platelet aggregation, and blood lipids |

No randomization (contrary to publication statement); description difficult to understand; selection of patients from larger population not clear; short verum period |

*(r)CS: (retrospective) case study; CT: controlled trial (not randomized); OS: observational study; RCT: randomized controlled trial (with Jadad sum score); MC: multicentre study.

**BM: Biomedicine (the “Western” “conventional” medicine); TM: Tibetan medicine; CAM: complementary or alternative medicine.

***I: intervention group (TM); C: control group (other treatment, placebo); D: total dropouts.

****U: unit (tablet, capsule, or pill); /d: per day; P28: Padma 28; PL: Padma Lax.

In the RCTs included were 2028 patients, 1020 of them received the Tibetan medicine treatment. Study duration ranged from 14 days to 12 months (mean = 114 days). Most RCTs investigated Padma 28 (n = 9) (the first study in [38], and [49–56]) or Padma Lax (n = 1) [57]. A whole medical system approach with a complex traditional TM intervention was applied in 3 studies on diabetes mellitus [43], arthritis, [58] or hepatitis B [59]. Tibetan yoga in lymphoma patients [60] and a single TM preparation (Zhi Byed 11) for postpartum haemorrhage [44] were each the subject of 1 RCT. One study [61] was declared an RCT but lacked randomization.

From those publications including herbal medicines, four did not provide details on the used medication [42, 58, 59, 62], two provided the name of the preparations but not the ingredients [43, 48], and two provided the name of the preparation and ingredients, but no information on the quantity of the ingredients [44, 63]. Data on both ingredients and their quantity was only available for Padma 28 and Padma Lax.

The duration of the non-randomized controlled trials was between 6 weeks and 6 months (mean = 43 d), 54% of the 678 patients received the verum Padma 28. Four non-randomized controlled trials included children with chronic respiratory tract infections [46, 64, 65] or juvenile arthritis [66]. One trial on adults included angina pectoris patients [61].

In the observational studies included, there were 1824 patients. The observation duration ranged from 15 days to 2 years (mean = 217 days). In some of the publications, the study duration was not clearly stated (the second study in [38], and [41]) or varied between participants [42, 45, 63]. Seven observational studies investigated Padma 28 (the second study in [38], and [47, 67–71]). One study each investigated Padma Lax [41] or a jewel pill (Byu-Dmar 13) [63]. Complex TM treatment was applied in 5 studies [39, 42, 45, 48, 62].

The duration of the case studies/series ranged widely from several days to 13.5 years [40]. Padma 28 was investigated in 4 case studies [40, 72–74], Padma Lax in 1 [75], and complex TM in another [76].

All studies included a total of 4684 patients, ranging from 1 to 967 per trial (mean = 117, SD = 187). Ten studies did not state the patients' sex (n = 1648, 35.2% of all patients in the present review) [40–42, 47, 56, 63, 65, 67, 71, 77]. From the other studies, 1080 patients (23.1%) were male and 1956 (41.8%) female. Data on age was available in 31 of 39 studies. Children (age 10 months to 16 years, n = 955) only were included in 5 studies [46, 64, 65, 70, 71]. Only 2 studies reported on ethnicity (Tibetan patients in both) [42, 58]. In 32 studies, dropouts were reported ranging from 0% (15 studies) to 53% [45] with a mean dropout rate of 15%. In 21 of the 28 trials of Padma 28 or Padma Lax, the mean drop out rate was 6%.

The checklist results for quality assessment are presented at item level in Table 3 for each study. Depending on study type and setting, 10 to 26 items could be answered. Had the assessment been for HTA purposes, only 1 case study [76] and 1 RCT [55] would have been eligible for inclusion in a HTA. Ignoring only one item (G2, provision of confidence intervals) would have raised that number to 13, including 8 RCTs that the Jadad score rated as good or very good quality. The Jadad score of the 15 RCTs (Table 4) reached a mean ± SD of 3.40 ± 1.35 (median = 4). Randomization scored 1.40 ± 0.51 (median = 1), blinding 1.20 ± 1.01 (median = 2), and drop-out reporting 0.80 ± 0.41 (median = 1). Studies on Padma 28 or Padma Lax had higher Jadad scores than studies on other treatments: 3.70 ± 1.06 (median = 4) versus 2.60 ± 1.51 (median = 2).

Table 3.

DIMDI HTA checklist results.

| Participants | Allocation | Intervention | Administration | Outcome | Drop-outs | Statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Item no. (label) * | A1 (in-/exclusion) | A2 (pre-defined) | A3 (health status) | A4 (diagnostic criteria) | A5 (representativity) | B1 (basic population) | B2 (comparable) | B3 (randomization) | B4 (blinded randomization) | B5 (confounders) | C1 (recording) | C2 (similar treatment) | C3 (other treatments) | C4 (placebo use) | C5 (placebo documented) | D1 (overmatching) | D2 (multicentre) | D3 (no crossover) | E1 (patient-centred) | E2 (recording) | E3 (blinded outcomes) | E4 (prognostic factors) | F1 (evaluable number) | F2 (reasons) | F3 (outcomes) | F4 (significance) | F5 (relevance) | G1 (correct) | G2 (CIs given) | G3 (graphics) | ||

| Brunner-LaRocca et al. 2005 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | N | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | Y | · | · | Y | N | Y | |||

| Cohen et al. 2004 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | N | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | N | · | ? | Y | N | · | · | Y | Y | N | |||

| Hürlimann1979/1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | ? | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Korwin-Piotrowska et al. 1992 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ? | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | ? | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Mehlsen et al. 1995 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | Y | N | |||

| Miller2009 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Randomized controlled trials | Namdul et al. 2001 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | ? | ? | Y | Y | · | N | · | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | · | Y | N | N | · | · | Y | N | N | ||

| Ryan1997 | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | N | · | Y | N | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Sallon et al. 1998 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | ? | Y | N | · | · | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Sallon et al. 2002 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | N | Y | |||

| Samochowiec et al. 1987 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | Y | |||

| Sangmo et al. 2007 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | ? | ? | N | Y | · | N | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Schrader et al. 1985 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Smulski and Wojcicki 1994 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Split et al. 1998 | Y | Y | N | N | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? | ? | Y | Y | · | N | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | ? | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brzosko et al. 1991 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | · | N | Y | Y | · | · | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | N | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Controlled trials |

Jankowski et al. 1991 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | · | N | Y | N | · | · | · | N | · | Y | N | Y | N | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | ||

| Mansfeld1988 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | ? | N | · | ? | Y | Y | · | · | · | N | · | Y | Y | ? | N | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | Y | |||

| Prusek et al. 1987 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | · | N | Y | ? | · | · | · | N | N | Y | Y | ? | N | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Wojcicki et al. 1986 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | · | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | N | · | Y | Y | Y | N | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aschoff et al. 1997 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | N | N | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Brzosko and Jankowski 1992 | Y | Y | ? | N | Y | · | · | · | · | ? | Y | ? | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Flück and Bubb 1970 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | N | Y | ? | · | · | · | · | Y | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Füllemann 2006 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | N | N | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | |||

| Gladysz et al. 1993 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | N | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Hürlimann 1979/2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | ? | Y | ? | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | N | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Observation studies | Jankowski et al. 1986 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | N | Y | ? | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | N | ||

| Jankowski et al. 1992 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | N | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Leeman at al. 2001 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | · | · | · | · | N | N | N | N | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | N | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Li 2001 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Neshar 2000 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | N | · | · | ? | · | · | · | · | N | N | N | |||

| Neshar 2007 | Y | Y | ? | Y | ? | · | · | · | · | ? | Y | · | · | · | · | · | Y | · | Y | Y | · | N | Y | N | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Pauwvlietet al. 1997 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | ? | Y | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Schleicher 1990 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | N | Y | ? | N | · | · | · | · | · | N | Y | · | · | ? | · | · | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bommeli et al. 2001 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | N | N | · | · | · | Y | · | Y | Y | · | N | Y | Y | N | · | · | Y | N | N | |||

| Changbar 1998 | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | · | · | · | Y | · | · | · | Y | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | N | |||

| Case studies | Feldhaus 2004 | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | · | · | ? | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | N | ||

| Feldhaus 2006 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | ? | Y | N | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | N | |||

| Günsche 2005 | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | · | · | Y | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | N | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | N | |||

| Rüttgers 2004 | Y | · | Y | Y | N | · | · | · | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | Y | N | · | N | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | N | |||

Y: yes; N: no; ?: unclear/not stated; ·: not applicable.

*Full item text in Table 1.

Table 4.

Jadad Score Results for Included RCTs.

| Randomization | Blinding | Drop-outs | Sum score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunner-La Rocca et al. 2005 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Cohen et al. 2004 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hürlimann 1979/1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Korwin-Piotrowska et al. 1992 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Mehlsen et al. 1995 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Miller 2009 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Namdul et al. 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ryan 1997 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Sallon et al. 1998 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Sallon et al. 2002 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Samochowiec 1987 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Sangmo et al. 2007 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Schrader et al. 1985 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Smulski and Wojcicki 1994 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Split et al. 1998 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

All studies followed conventional “Western” medical diagnoses. Additional traditional TM diagnostics were recorded in 11 studies that investigated the traditional multimodal treatment. In 9 of them, the Tibetan diagnosis was used to plan the therapy [39, 42, 43, 45, 48, 58, 59, 62, 76].

Thirty studies including 3497 patients (74.7% from all included studies) investigated single formulations: Padma 28 (n = 25 studies), Padma Lax (3), Byu-Dmar 13 (1), and Zhi Byed 11 (1). The complex traditional Tibetan treatment was studied in 9 trials that included a total of 1140 (24.3%) patients. Here, and in the Padma 28 studies, the treated conditions varied widely. For example, Padma 28 was investigated for arteriosclerosis, infections, neurological disorders, venous insufficiency, arthritis, and hypercholesteraemia.

Assessed outcomes included clinical outcomes such as symptom scales (n = 37 studies), laboratory tests (19), clinical tests (such as ankle/brachial pressure index, blood pressure, or weight; 9), and other (9), such as microbiology, histology, or the need for conventional medication. The authors drew positive conclusions on their data in 34 studies. In 2 RCTs, TM was found to be inferior to conventional medicine, but better than placebo [44, 46]. In one study, only 1 of 5 outcomes improved [60]; in 2 studies the primary outcome did not change significantly while secondary outcomes did [42, 52]. The comparison of the traditional and a not further specified “special” Tibetan medicine [59] resulted in comparable clinical improvements. The remaining studies found no significant differences to controls [49, 65], or their authors were doubtful about the observed effects [39]. Statements about adverse effects were included in 23 studies, in 11 of them no adverse effects were reported, and 2 studies did not mention the number of patients with adverse effects [39, 53]. The remaining 10 studies reported adverse effects with a range from 5% to 55% of the patients.

Some disease groups were researched in several trials. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease was treated with Padma 28 in 9 studies (6 RCTs, (the first study in [38], [51–55])) 1 observation study, (the second study in [38]) and 2 case studies [40, 72]. Maximum walking distance increased in 5 studies (the first study in [38], and [51, 53–55]). Both case studies and the observational study reported a general clinical improvement. The ankle/brachial pressure index in 1 RCT [52] was unchanged. All authors made a positive conclusion regarding Padma 28.

Five studies (3 non-randomized controlled trials [46, 53, 65] and 2 observation studies [70, 71]) investigated Padma 28 for recurrent respiratory tract infections in children. Improvements were seen for frequency of infections [70, 71] or spontaneous bacterial activity [64]. In 1 of the controlled trials, no significant difference to standard therapy was found [65], and in another study, inferiority to other therapies was reported [46].

Osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis was treated in three trials: 1 RCT [58] and 1 observational study [62] with the traditional multimodal approach, and with Padma 28 in 1 controlled trial [66]. All studies reported pre-/post-improvements or superiority to controls regarding symptom severity.

Padma Lax in chronic constipation was the subject of three studies (1 RCT [57], 1 controlled trial [75], and 1 observational study [41]). All reported clinical improvements.

In 3 other trials, hepatitis B patients were either treated with a “special” TM (that was not further specified) in comparison to traditional TM (1 RCT [59]) or with Padma 28 (2 observational studies [47, 69]). All publications reported positive results for laboratory outcomes. The comparison of traditional and “special” traditional TM found comparable improvements but did not achieve seroconversions.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we presented an overview of the clinical research on traditional Tibetan medicine (TM) that is currently available in the West. Three quarters of the included studies tested single formulations, most of them products of a single company. One quarter investigated the traditional multimodal TM approach. Studies were very heterogeneous regarding study type and size, treated conditions, treatments, measured outcomes, and quality.

In this, to our knowledge, first systematic overview of clinical TM research available in the West, we tried to minimize subjectivity using pre-defined systematic methods wherever possible (data extraction sheets, established quality assessment tools). However, the small number of trials scattered over a whole medical system and very heterogeneous treated diseases prohibited more formal or in-depth analyses.

Despite the broad literature search, some studies may not have been identified, for various reasons. Although Mongolian and Tibetan medicine are not completely identical, we have included “mongolian” in the search terms in order to find as much relevant literature as possible. We did not search for single TM interventions such as bathing or bloodletting and assumed that they are well covered under the umbrella term “medicine.” Although we detected with this search a study on Tibetan yoga [60], we possibly missed other studies. Furthermore, publication bias could have had occurred, as some papers [11, 15, 58] indicated the existence of studies that have not been published (or at least not in indexed journals) [77–82]. Several papers were not identified by our search strategy in the literature databases, but could have been found searching for “Padma 28” or “Padma Lax.” Clearer labelling of TM studies in the future would be helpful. On the other hand, our search seems to have been partly redundant, as all identified publications could have been found with fewer search terms. The main limitation is that our language restriction excluded articles in Russian, Tibetan, and Chinese. This literature was not accessible for us. Furthermore, we learned from our field work and from discussions with Western and Chinese manufacturers during an interdisciplinary symposium on TM [16] that most literature on clinical research published in Tibetan is not available in indexed journals and that most research published in Chinese addresses preclinical questions.

The evaluated literature presented a high number of studies without a control group. Only a few single products were subject to in-depth investigation. Both facts indicate an early stage of research in a new and largely unexplored field where only few focused inquiries exist. The predominating countries of origin (>2/3 European) and the 70% of studies on Padma products among the included literature are consequences of the language restrictions of our search as well as of the historical development of TM utilization in the West. Although they are prescribed in a standardized and nonindividualized fashion, the Padma products are a genuine Tibetan medication according to manufacturers, study authors, and independent experts [17, 83, 84]. Adaptation of constituents to local situation and ecology is an accepted practice in TM. It was done in one study when Tibetan physicians reduced the traditional Byu-Dmar 25 by 12 ingredients to comply with Tibetan pharmacopoeia and European regulations, resulting in Byu-Dmar 13 [63]. A similar strategy might have been used in two other studies [39, 62].

The heterogeneous nature of the included studies demanded the use of quality assessment instruments that were suitable for diverse study designs, but have the general disadvantage of allowing only rough estimates of the assessed quality. Nevertheless, they allowed spotting the more obvious deficiencies that are symptomatic of research at an early stage and that future research can avoid with improved methodology on the grounds of evidence-based medicine. Case studies and observational studies are useful to gather information on traditional usage and settings and to identify areas where controlled studies seem promising. Then, to provide higher-level evidence, more RCTs will be needed. Methodological issues such as small samples, insufficiently described populations in many studies, pre-/post-comparisons of treatment within a group, or comparator treatments without clinical relevance all indicate that TM research as seen through the Western literature is still at a nascent stage. Furthermore, the quality of most studies and the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes make clear conclusions impossible.

5. Conclusion

The clinical research on traditional Tibetan medicine (TM) that is available in Western industrialized countries is scarce and scattered over a whole medical system, but shows interesting results. Better research methodology should be applied, and larger trials are needed, as is a general overview of traditional usage to inform future clinical research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported within a grant of the Chair for Complementary Medicine Research, funded by the Karl and Veronica Carstens Foundation, Essen, Germany. The authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Dunkenberger T. Das Tibetische Heilbuch. Aitrang, Germany: Windpferd Verlagsgesellschaft; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner P. Tibetan medicine. In: Gale T, editor. The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine. 2nd edition. Detroit, Mich, USA: Longe; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dash V. Tibetan Medicine: Theory and Practice. Delhi, India: Sri Satguru Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samel G. Tibetan Medicine. London, UK: Little, Brown & Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witt CM, Berling N, Thingo N, Cuomo M, Willich SN. Evaluation of medicinal plants as part of Tibetan medicine—prospective observational study in Sikkim and Nepal. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2009;15(1):59–65. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asshauer E. Tibets Sanfte Medizin: Heilkunst vom Dach der Welt. 4th edition. Zürich, Switzerland: Oesch; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaitonde BB, Kurup PN. Regional overview: South-East Asia region. In: Bodeker G, Ong C, Grundy C, et al., editors. WHO Global Atlas of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Kobe, Japan: World Health Organisation, Centre for Human Development; 2005. pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwabl H, Geistlich S, McHugh E. Tibetische Arzneimittel in Europa: Historische, praktische und regulatorische Aspekte. Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 2006;13(supplement 1):1–6. doi: 10.1159/000090732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badmaev V., Jr. The continuation of the Badmaev family tradition in its 5th generation. AyurVijnana. 2000;7 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saller R. Tibetische Heilmittel bei Chronischen Erkrankungen. Zürich, Switzerland: 2005. Tibetische Heilmittel bei chronischen Erkrankungen, Einleitung. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melzer J, Brignoli R, Diehm C, et al. Treating intermittent claudication with Tibetan medicine Padma 28: does it work? Atherosclerosis. 2006;189(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badmaev V. Medicine tested by Science: an effective botanical treatment for circulatory deficience due to atherosclerosis. Nutri-Cosme-Ceutici, 6.8.2.2002, Rome, Italy, 2002.

- 13.Ueberall F, Fuchs D, Vennos C. Das anti-inflammatorische Potential von Padma 28: Übersicht experimenteller Daten zur antiatherogenen Wirkung und Diskussion des Vielstoffkonzepts. Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 2006;13(supplement 1):7–12. doi: 10.1159/000090669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weseler A, Saller R, Reichling J. Comparative investigation of the antimicrobial activity of Padma 28 and selected European herbal drugs. Forschende Komplementärmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde. 2002;9(6):346–351. doi: 10.1159/000069234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Röösli MB. Systematische Übersichtsarbeit: Klinische Studien zur Wirksamkeit und Sicherheit des phytotherapeutischen Kombinationspräparats PADMA 28, Universität Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, 2009.

- 16.Witt CM, Craig S, Cuomu M. Tibetan Medicine Research—From Current Evidence to Future Strategies: Advice from an Interdisciplinary Conference. Essen, Germany: KVC Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geistlich S, Schwabl H. Von der Tradition zur ‘evidence-based medicine’. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 2003;15:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerke B. Tradition and modernity in Mongolian medicine. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2004;10(5):743–749. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plakun EM. Psychiatry in Tibetan Buddhism: madness and its cure seen through the lens of religious and national history. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry. 2008;36(3):415–430. doi: 10.1521/jaap.2008.36.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxer M. Journeys with Tibetan medicine [M.S. thesis] 2004. http://www.anyma.ch/journeys/doc/thesis.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navchoo IA, Buth GM. Medicinal system of Ladakh, India. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1989;26(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations. World, Map No. 4170. October 2006, http://www.scribd.com/doc/217671/Map-The-World.

- 23.Wolters Kluwer. Ovid Technologies, 2010, http://www.ovid.com.

- 24.DIMDI. Datenbanken A-Z, 2010, http://www.dimdi.de/static/de/db/dbinfo/index.htm.

- 25. Bibliothek der Charité, Datenbanken, 2010, http://www.charite.de/bibliothek/datenbanken.htm.

- 26. ZB MED, MedPilot, 2010, http://www.medpilot.de.

- 27.Google. Google Scholar, 2010, http://scholar.google.com.

- 28.Padma AG. Padma 28—Literaturverzeichnis 2/09, 2009, http://www.padma.ch/Literature/Literature_Padma28_Feb2009.pdf.

- 29.Aschoff J. Tibetische Medizin—Kommentierte Bibliographie. Ulm, Germany: Fabri; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institut für Ost-West-Medizin. Kursreihe Einführung in die Tibetische Medizin, 2008, http://www.ostwestmedizin.de/

- 31. Interessengemeinschaft Tibetische Medizin, Programm im Detail: der Ausbildung zur Therapeutin tibetische Medizin, Interessengemeinschaft Tibetische Medizin, 2011, http://www.ig-tibetische-medizin.ch/images/ausbildung/Ausbildung_Uebersicht.pdf.

- 32.New Yuthog Institute. 4 year Tibetan Medicine course, 2011, http://www.newyuthok.it/en/ctibetanmedicine.html.

- 33. Access, Microsoft, Redmond, Wash, USA, 2003.

- 34. Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, Wash, USA, 2003.

- 35.Ekkernkamp M, Lühmann D, Raspe H. Methodenmanual für ‚HTA-Schnellverfahren’ und exemplarisches ‚Kurz-HTA’. Die Rolle der quantitativen Ultraschallverfahren zur Ermittlung des Risikos für osteoporotische Frakturen. Vol. 34. Sankt Augustin, Germany: Asgard Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moher D, Jadad AR, Tugwell P. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials. Current issues and future directions. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1996;12(2):195–208. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300009570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hürlimann F. Eine lamaistische Rezeptformel zur Behandlung der peripheren arteriellen Verschlusskrankheit. Schweizerische Rundschau Fur Medizin. 1979;67:1407–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leeman E, Dhonden Y, Woolf M. A Phase I Trial of Tibetan Medicine for Advanced Breast Cancer, 2001, http://www.cbcrp.org/research/PageGrant.asp?grant_id=90.

- 40.Bommeli C, Bohnsack R, Kolb C. Praxiserfahrungen mit einem Vielstoffpräparat aus der tibetischen Heilkunde. Erfahrungsheilkunde. 2001;50(11):745–756. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flück H, Bubb WP. Eine lamaistische Rezeptformel zur Behandlung der chronischen Verstopfung. Schweizerische Rundschau für Medizin Praxis. 1970;59(33):1190–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li F. Ergebnisse der Behandlung von symptomatischen Patienten mit tibetanischer Medizin, die an einer Infektion mit Helicobacter Pylori (HP) leiden. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Akupunktur. 2001;44(3):183–185. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Namdul T, Sood A, Ramakrishnan L, et al. Efficacy of Tibetan medicine as an adjunct in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(1):175–176. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller S, Tudor C, Thorsten V, et al. Randomized double masked trial of Zhi Byed 11, a Tibetan traditional medicine, versus misoprostol to prevent postpartum hemorrhage in Lhasa, Tibet. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2009;54(2):133.e1–141.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neshar D. Clinical case Study of Cancer (Dres-ned) patients treated at Men-Tsee-Khang’s Bangalore Branch Clinic for the period of 27 month from November 2002 to February 2005. Journal of Men-Tsee-Khang. 2007;4(1):50–68. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prusek W, Jankowski A, Radomska G, et al. Immunostimulation in recurrent respiratory tract infections therapy in children. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 1987;35(3):289-–2302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brzosko W, Jankowski A. PADMA 28 bei chronischer Hepatitis B: Klinische und immunologische Wirkungen. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 1992;7-8(supplement 1):13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neshar D. Efficacy of traditional Tibetan medicine against diabetes mellitus. Journal of Men-Tsee-Khang. 2000;2(2):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunner-La Rocca HP, Schindler R, Schlumpf M, et al. Effects of the Tibetan herbal preparation Padma 28 on blood lipids and lipid oxidisability in subjects with mild hypercholesterolaemia. VASA. 2005;34(1):11–17. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.34.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korwin-Piotrowska T, Nocon D, Stankowska-Chomicz A, Starkiewicz A, Wojcicki J, Samochowiec L. Experience of Padma 28 in multiple sclerosis. Phytotherapy Research. 1992;6(3):133–136. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehlsen J, Drabaek H, Petersen J, et al. Der Effekt einer tibetischen Kräutermischung (Padma 28) auf die Gehstrecke bei stabiler Claudication intermittens. Forschende Komplementärmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde. 1995;2(5):240–245. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sallon S, Beer G, Rosenfeld J, et al. The efficacy of Padma 28, a herbal preparation, in the treatment of intermittent claudication: a controlled double-blind pilot study with objective assessment of chronic occlusive arterial disease patients. Journal of Vascular Investigation. 1998;4(3):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samochowiec L, Wojicki J, Kosminder K. Wirksamkeitsprüfung von Padma 28 bei der Behandlung von Patienten mit chronischen arteriellen Durchblungsstörungen. Polbiopharm Reports. 1987;(22):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrader R, Nachbur B, Mahler F. Die Wirkung des tibetanischen Kräuterpraparates Padma 28 auf die Claudicatio intermittens. Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1985;115(22):752–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smulski HS, Wojcicki J. Plazebokontrollierte Doppelblindstudie zur Wirkung des tibetanischen Kräuterpräparates Padma 28 auf die Claudication intermittens. Forschende Komplementärmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde. 1994;1:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Split W, Szydlowska M, Brzosko W. The estimation of the action of Padma-28 in the treatment of ischaemic brain stroke. European Journal of Neurology. 1998;5(supplement 1):p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sallon S, Ben-Arye E, Davidson R, et al. A novel treatment for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome using Padma Lax, a Tibetan herbal formula. Digestion. 2002;65(3):161–171. doi: 10.1159/000064936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryan M. Efficacy of the Tibetan treatment for arthritis. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44(4):535–539. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sangmo R, Dolma D, Namdul T, et al. Clinical trial of Tibetan medicine in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Men-Tsee-Khang. 2007;4(1):32–49. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, et al. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2253–2260. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wojcicki J, Samochowiec L, Dolata C. Controlled double-blind study of Padma 28 in angina pectoris. Herba Polonica. 1986;32(2):107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pauwvliet C. A pilot study on the effect of Tibetan medicine on patients with rheumatic diseases. In: Aschoff J, Rösing I, editors. Tibetan Medicine. Ulm, Germany: Fabri; 1997. pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aschoff J, Tashigang T, Maier J. Clinical trial in migraine prophylaxis with a multicomponent Tibetan jewel-pill. Transfer problems of Tibetan to Western medicine, demonstrated, “pars pro toto” on the Aconite medical plants in our Tibetan prescription. In: Aschoff J, Rösing I, editors. Tibetan Medicine,Verlag. Ulm, Germany: Fabri; 1997. pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jankowski S, Jankowski A, Zielinska S, Walczuk M, Brzosko WJ. Influence of Padma 28 on the spontaneous bactericidal activity of blood serum in children suffering from recurrent infections of the respiratory tract. Phytotherapy Research. 1991;5(3):120–123. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mansfeld H. Beeinflussung rezidivierender Atemwegsinfekte bei Kindern durch Immunostimulation. Therapeutikon. 1988;2:p. 707. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brzosko WJ, Jankowski A, Prusek W, Ollendiek H. Influence of Padma 28 and the thymus extract on clinical and laboratory parameters of children with juvenile chronic arthritis. International Journal of Immunotherapy. 1991;7(3):143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schleicher P. Wirkung von Padma 28 auf das Immunsystem bei Patienten mit Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrom im Stadium des Pre-AIDS. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 1990;2:p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Füllemann F. Padma 28 in der Behandlung von chronischen Zahnpulpitiden: Eine Praxisbeobachtung an 49 Fällen. Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 2006;13(supplement 1):28–30. doi: 10.1159/000090734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gladysz A, Juszczyk J, Brzosko WJ. Influence of Padma 28 on patients with chronic active hepatitis B. Phytotherapy Research. 1993;7(3):244–247. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jankowski A, Drabik E, Szysko Z, et al. Die Behandlung rezidivierender Atemwegsinfektionen bei Kindern durch Aktivierung des Immunsystems. Therapiewoche Schweiz. 1986;2(1):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jankowski A, Jankowska R, Brzosko W. Behandlung infektanfälliger Kinder mit Padma 28. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 1992;7-8(supplement 1):22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feldhaus S. Ganzheitliches Therapiekonzept bei pAVK. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 2004;16:p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Günsche M. Therapieresistenz bei Tagesmüdigkeit, Antriebsschwäche und Konzentrationsschwierigkeit. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 2005;17:p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rüttgers J. Crux medicorum: das offene Bein. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin. 2004;16:278–280. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feldhaus S. Behandlung der chronischen Obstipation eines tetraplegischen Patienten mit dem tibetischen Arzneimittel Padma Lax—ein Fallbericht. Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 2006;13(supplement 1):31–32. doi: 10.1159/000090707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Changbar S. Tibetan medicine in the treatment of aplastic anaemia. AyurVijnana. 1998;4 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ryan M. Measuring the efficacy of Tibetan treatment for acute hepatitis. Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference on Ethnic Culture and Folk Knowledge of Russian Acadamy of Sciences; 1994; Moscow, Russia. Moscow University Press; [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sommogy S, Schleicher P. Therapie der peripheren arteriellen Verschlusskrankheit (PAVK) mit Padma 28. Bericht 26.6, Abteilung für Gefäßchirurgie, Technische Univerität München und Zytognost GmbH, München, Germany, 1990.

- 79.Samochowiec L, Wojcicki J, Kosmider K, et al. Wirksamkeitsprüfung von Padma 28 bei der Behandlung von Patienten mit chronischen arteriellen Durchblutungsstörungen. Herba Polonica. 1987;33:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Winther K, Kharazmi A, Himmelstrup H, Drabaek H, Mehlsen J. PADMA-28, a botanical compound, decreases the oxidative burst response of monocytes and improves fibrinolysis in patients with stable intermittent claudication. Fibrinolysis. 1994;8(2):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Panjwani H, Brzosko W. Influence of selected immunocorrecting drugs on intellectual function of the brain due to arteriosclerosis. Nowiny Lekarskie. 1998;5:665–670. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hasik J, Klinkiewicz H, Linke K, et al. Effectiveness of duodenal ulcer disease treatment by PADMA 28. Nowiny Lekarskie. 1992;2:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kalsang T. Interview with KPR [pers. comm.], Dharamsala, India, October 2008.

- 84.Tamdin T. Tibetische Heilmittel bei Chronischen Erkrankungen. Zürich, Switzerland: November 2005. Challenges and prospects of research in Tibetan medicine. [Google Scholar]