Abstract

Hedgehog (Hh) signaling is vital for the patterning and organogenesis of almost every system. The specificity of these developmental processes is achieved through a tight spatio-temporal regulation of Hh signaling. Mice with defective Hh signal exhibit a wide spectrum of anomalies, including Vertebral defects, Anal atresia, Cardiovascular anomalies, Tracheoesophageal fistula, Renal dysplasia, and Limb defects, that resemble strikingly the phenotypes observed in VACTERL association in humans. In this review, we summarize our current understanding of mammalian Hh signaling and highlight the relevance of various mouse models for studying the etiology and pathogenesis of VACTERL association. In addition, recent advances in genetic study for unraveling the complexity of genetic inheritance of VACTERL and the implication of the Sonic hedgehog pathway in disease pathogenesis are also discussed.

Key Words: Ciliopathy, Congenital diseases, Hedgehog signaling

VACTERL association refers to a condition in which a constellation of congenital malformations occurs together non-randomly and more often than expected by chance. These malformations include Vertebral defects, Anal atresia, Cardiovascular anomalies, Tracheoesophageal fistula, Renal dysplasia, and Limb defects. Each child may present with a unique condition or in combination with other similar conditions, such as Klippel-Feil and Goldenhar syndrome [David et al., 1996], but usually patients with at least 3 component features are required for diagnosis. The etiology of these anomalies remains largely unknown, and the causes have been found heterogeneous and pathogenetically unrelated. Therefore, VACTERL is considered as a polytopic developmental field defect caused by differentiation anomalies occurred during embryogenesis, leading to a spectrum of birth defects affecting multiple organ systems [Martínez-Frías et al., 2000; Hersh et al., 2002]. VACTERL association has been attributed to Hedgehog (Hh) signaling defects since perturbed Hh signaling in mice phenocopies many of these human deformities. In this review, we provide an overview of the mammalian Hh signaling pathway and summarize recent insights into the disease etiology of VACTERL gained by mouse and human genetic studies.

Hedgehog Signaling in Mammals

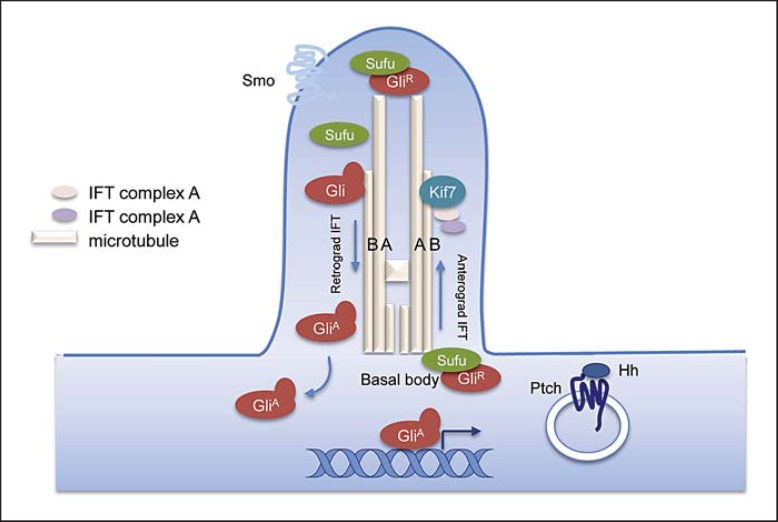

Sonic, Indian and Desert Hedgehog are the 3 secreted ligands for Hh signaling in mammals. They bind to the transmembrane Hh-receptor Patched (Ptch1 and Ptch2), which regulate the signaling activity of Smoothened (Smo). In absence of Hh, Ptch renders Smo inactive. Upon Hh binding to Ptch, Smo is activated to signal downstream. Membrane trafficking of Ptch and Smo is critical for Hh signaling. Endocytosis of Ptch is implicated in shaping the signal gradient [Incardona et al., 2000; Torroja et al., 2004], while Smo trafficking to the primary cilium is required for Hh signal transduction [Goetz and Anderson, 2010]. The downstream signal transduction is not well understood (fig. 1). Three members of the Gli zinc-finger family of transcription factors (Gli1, 2, 3) are responsible for transducing Hh response: Gli1 appears to be a constitutive activator, whereas Gli2 and Gli3 possess both activator and repressor functions. In absence of Hh signaling, partial degradation of Gli2 and Gli3 by the proteasome results in the formation of C-terminally truncated Gli repressor (Gli2R and Gli3R), which enters the nucleus to suppress the transcription of Hh target genes. Upon Hh stimulation, active Smo blocks the formation of GliR and promotes the formation of Gli activators (GliA) through inhibiting the proteolysis of Gli proteins and unleashing the negative regulation of Suppressor of fused (Sufu) and kinesin family protein 7 (Kif7). The coordinated regulation of GliA and GliR results in the differential activation of Hh target genes, conferring a graded Hh signaling response [Hui and Angers, 2011].

Fig. 1.

Hedgehog signal transduction. In absence of Hh signal, Sufu-Gli complexes are localized at the basal body, where Gli is processed to GliR by proteolysis. Upon Hh activation, Smo is unleashed from Ptch, followed by Ptch internalization and accumulation of Smo in the primary cilia. Sufu-Gli complexes then translocate to the tip of the primary cilium by anterograde IFT. Subsequently, active Smo promotes the dissociation of Sufu-Gli complexes and activation of unprocessed Gli to GliA. The microtubule-dependent (retrograde IFT) translocation of GliA to nucleus triggers gene transcription of Hh target genes [Hui and Angers, 2011].

Multiplicity of Gli Proteins in Mouse and Human Development

Transcriptional output of Hh signaling is governed by the combinatorial action of Gli1, Gli2 and Gli3. Multiplicity of Gli proteins in mammalian cells allows a 2-tiered control of Hh signal transduction, where Gli2 and Gli3 are the primary transducers, and Gli1 acts as the secondary transducer refining Hh signaling. In addition, the paradoxical nature of Gli2 and Gli3 (GliA and GliR) further confers the context-dependent gene regulation and generates the graded Hh signaling responses.

Gli1 is a direct Hh target gene and its expression in early mouse embryos is regulated by Gli2 and Gli3. Gli1 behaves as a robust positive activator to potentiate the transcriptional output of Hh signaling. It has been implicated in a wide variety of human cancers [Teglund and Toftgård, 2010; Yang et al., 2010], but GLI1 mutations have not been reported in any human congenital diseases. Consistent with this, Gli1 is dispensable for mouse development and Gli1–/– mice do not show any severe developmental defects [Park et al., 2000; Bai et al., 2004].

Gli2 and Gli3, on the other hand, act as both activator and repressor. Gli2 functions primarily as an activator, albeit also as a weak repressor in some circumstances, while Gli3 is predominantly a repressor. Both Gli2 and Gli3 are essential for mouse development. Loss-of-function and dominant-negative GLI2 mutations have been associated with holoprosencephaly-like features and pituitary malformations in humans [Roessler et al., 2003, 2005]. Gli2–/– mice phenocopy the human phenotypes, exhibiting midline anomalies [Mo et al., 1997] and pituitary defects [Wang et al., 2010]. More remarkable is the fact that a catalog of disease-causing mutations of GLI3 have been identified in patients with different polydactyly syndromes or features, including Pallister-Hall syndrome (PHS) [Kang et al., 1997], Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS) [Vortkamp et al., 1991], acrocallosal syndrome [Elson et al., 2002] as well as preaxial and postaxial polydactyly [Radhakrishna et al., 1997, 1999]. GLI3 mutations in PHS patients are predicted to generate a truncated mutant protein with constitutive GLI3 repressor function [Kang et al., 1997; Shin et al., 1999], while deletion or truncating GLI3 mutations leading to loss of functional GLI3 represent the major cause of GCPS [Shin et al., 1999; Johnston et al., 2010]. Mouse models with different Gli3 mutations exhibit phenotypes, which recapitulate those found in the patients [Hui and Joyner, 1993; Böse et al., 2002].

Distinct and overlapping functions of the 3 Gli proteins have been illustrated in the phenotypic analyses of double mutant mice. More severe phenotypes are usually observed in the double mutants, indicating the functional redundancy among Gli1, Gli2 and Gli3. For instance, Gli1–/–;Gli2+/– mice have reduced viability and exhibit lung and neural tube defects that are not found in either Gli1–/– or Gli2+/– [Park et al., 2000]. Similarly, exacerbated phenotypes in the limb, sternum, vertebral column, and mandible are also observed in Gli2–/–;Gli3+/– mice [Mo et al., 1997]. These mutant studies also revealed that GliA and GliR play differential roles in Sonic hedgehog (Shh)-dependent developmental processes. In the developing limb, Gli3 is the key target of regulation by Shh signaling [Litingtung et al., 1998; te Welscher et al., 2002a, b], whereas Gli2 is required for Shh-dependent hair follicle development [Mill et al., 2003].

Primary Cilium in Hh Signal Transduction

Primary cilium is a microtubule based non-motile organelle that emanates from the cell surface of quiescent cells. It acts as a sensory organelle to coordinate various signaling pathways, which are critical in both embryonic development as well as adult tissue homeostasis [Goetz and Anderson, 2010]. Assembly of the cilia is mediated by intraflagellar transport (IFT), by which large complexes called IFT particles are moved from the cell body into and along the ciliary microtubules. These IFT particles comprise more than 20 subunits collectively organized into 2 subcomplexes (A and B). The IFT particles carried to the ciliary tip (anterograde IFT) are associated with axonemal precursors for microtubule elongation, while the turn-over products are brought back from the tip to the cell body for recycling by the retrograde IFT. Kinesin-2 and cytoplasmic dynein 2 are the motors that respectively power anterograde and retrograde IFT.

Integrity of the primary cilium is essential for mammalian Hh signal transduction [Huangfu et al., 2003]. In the absence of Hh ligand, Ptch resides in the ciliary membrane and prevents Smo from entering primary cilia. In these Smo-inactive cells, Gli proteins are inhibited by the formation of a cytoplasmic complex with Sufu, and Gli proteins are processed by the proteasome to form GliR. Upon Hh stimulation, Ptch exits the cilium and consequently triggers the ciliary accumulation of active Smo [Rohatgi et al., 2007]. Translocation of Kif7 to the ciliary tip is also induced by Hh signal. Kif7 may act as a motor to mediate the ciliary trafficking of Gli proteins. In this process, Kif7 activity depends on IFT and the presence of cilia. For example, loss of IFT B complex (e.g. Ift172) blocks ciliogenesis and attenuates Kif7 trafficking, such that Kif7maki;Ift172wim double mutants exhibit phenotypes indistinguishable from that of Ift172wim mutant [Endoh-Yamagami et al., 2009; Liem et al., 2009]. Furthermore, active Smo progressively promotes the dissociation of Gli from Sufu and induces the microtubule-dependent translocation of Gli to the nucleus to activate Hh target gene transcription [Humke et al., 2010; Tukachinsky et al., 2010]. In mice, loss of functional complex B subunits (Ift172avc1, lft172wim and lft172 null) or the kinesin-2 motor typically compromises anterograde IFT, leading to defective ciliary assembly and an attenuated Shh pathway [Huangfu and Anderson, 2005; Liu et al., 2005; Houde et al., 2006; Ocbina and Anderson, 2008], while most mutations in the retrograde IFT motor dynein 2 or IFT complex A lead to the formation of short stumpy cilia and accumulation of Hh pathway components in cilia [Huangfu and Anderson, 2005; May et al., 2005].

Mouse Models of Hedgehog Signaling for VACTERL Association

Hh signaling is implicated in many aspects of animal development, from left-right asymmetry, dorsoventral patterning of CNS and somites, and limb patterning to organogenesis. Importantly, mice lacking various Hh signaling components and cilia-related genes exhibit VACTERL-like defects as summarized in table 1. In particular, Shh, Gli2, Gli3, Ift25, and Ift172 mutant mice have vertebral anomalies; Shh null mice develop truncated limbs; Gli3–/–, Gli3Δ699/Δ699, Kif7–/–, Ift25–/–, and Ift172avc mutants exhibit polydactyly; Shh–/–, Gli2–/–, Gli3–/–, Gli3Δ699/Δ699, Ift172avc, and Ift25–/– mutants all show various foregut and hindgut anomalies as well as cardiac defects; and Shh–/–, Gli3Δ699/Δ699, Gli2–/–;Gli3–/–, and Ift172avc mutant mice display renal anomalies. Similarly, ablation of Hh target genes, such as Hoxd13 and Foxc2, in mice also results in mutant phenotypes related to VACTERL association, further suggesting the biological relevance of Hh signaling in VACTERL pathogenesis.

Table 1.

Knockout mouse models featuring VACTERL-like phenotypes

| Genotype | Mouse phenotypes | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vertebrae | anal | cardiac | tracheo-esophagel | renal | limb | ||

| Shh–/– | agenesis of vertebral column | anal atresia | abnormal heart looping | TEF | solitary kidney | Limb truncation | Chiang et al., 1996; Litingtung et al., 1998; Ramalho-Santos et al., 2000 |

| Gli2–/– | agenesis of vertebral body | imperforate anus | – | esophageal and tracheal stenosis | – | hypoplasia | Motoyama et al., 1998 |

| Gli3–/– | neural arches fusion | anal stenosis | – | – | – | polydactyly | Motoyama et al., 1998 |

| Gli2–/–;Gli3–/– | agenesis of vertebral column | anal atresia | abnormal heart looping | agenesis of trachea and esophagus | horseshoe kidney | polydactyly | Motoyama et al., 1998 |

| Gli3Δ699/Δ699 | premature mineralization, dorsal arch fused with vertebral body | imperforate anus | – | agenesis of trachea and esophagus | single kidney, renal aplasia, dysplasia | normal limbs with an extra digit | Böse et al., 2002 |

| Ift172avc | agenesis of vertebral body | anal atresia | atrio-ventricular septal defect | hypoplastic esophagus and enlarged trachea | renal dysplasia with hypoplastic glomeruli | polydactyly | Friedland-Little et al., 2011 |

| Ift25–/– | sternal vertebrae defects | ND | left-right asymmetry defects, VSD, ASD | tracheal stenosis | – | polydactyly | Keady et al., 2012 |

| Foxc2–/– | absence of vertebral body, split neural arches, lack of spinous processes, rib fusion | – | interrupted aortic arch, ventricular septal defect | – | Hypoplastic kidney, hydroureter | – | Iida et al., 1997; Kume et al., 2000a, b |

| Hoxd13–/– | – | Disorganized anorectal region | – | – | kidney agenesis | neotenic limbs, synpolydactyly | Kondo et al., 1996; Mandhan et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 1995 |

EA = Esophageal atresia; TEF = trachea-esphageal fistula; VSD = ventricular septal defect; ASD = atrioventricular septal defect; ND = not determined.

Vertebral Column Defects

Approximately 60–80% of the VACTERL patients have vertebral anomalies, including segmentation defects, vertebral fusions, supernumerary or absent vertebrae, and other forms of vertebral dysplasia. In addition, these vertebral anomalies are commonly accompanied by rib deformities. Shh is secreted from the notochord and floor plate cells, and patterns the formation of vertebral column. Shh induces somite compartmentalization to generate dermomyotome and sclerotome. The sclerotomal mesenchyme later gives rise to the skeletal elements of the vertebral column and ribs, whereas dermomyotome develops into muscle and skin. Shh null embryos exhibit severe patterning defects of somites and a complete absence of the vertebral column [Chiang et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2001a]. Expression of Shh in the floor plate or the notochord induces expression of the sclerotome marker Pax1 [Fan and Tessier-Lavigne, 1994; Johnson et al., 1994]. Specific deletion of Shh from either the floor plate or the notochord illustrates that Shh expression in the notochord is sufficient for patterning the vertebral column [Choi et al., 2012]. Gli2 and Gli3 are differentially expressed and localized to the medial and dorsal parts of the developing sclerotome, respectively [Hui et al., 1994; Mo et al., 1997]. Mice lacking Gli2 exhibit a vertebral phenotype, such as absence of the vertebral bodies, similar those of Shh and Pax1 null mice. On the other hand, Gli3–/– mice exhibit a vertebral phenotype, including abnormal development of the neural arches, which is distinct from those of Gli2–/– and Shh–/– mice. Since Gli2–/–;Gli3+/– mice show a more severe vertebral column phenotype than the single mutants, in which chondrogenesis in multiple regions along the ventral part of the vertebral column is affected, it is conceivable that both Gli2 and Gli3 function in the reception of notochordal Shh signal and possess redundant function in the development of vertebral bodies [Mo et al., 1997]. Intriguingly, sternum and rib defects frequently occur in Shh–/–, single or double mutants of Gli2 and Gli3, nicely resembling the human conditions. In addition, mutant mice of the hypomorphic allele of Ift172 (Ift172avc), in which mutant Ift172 transcripts are unstable, leading to truncated cilia, reduced ciliary abundance, as well as attenuated Hh signaling, also lack vertebral bodies [Friedland-Little et al., 2011]. On the other hand, loss of another IFT B gene Ift25 or Kif7 only cause a mal-alignment of the sternal vertebrae, and the vertebral bodies of Ift25 null, Ift25neo/neo or Kif7–/– mutants remain intact [Cheung et al., 2009; Keady et al., 2012].

Anal Atresia

Anal atresia and imperforate anus occur in approximately 55–90% of VACTERL patients as part of anorectal malformations (ARM). In the developing gastrointestinal tract, Shh and Indian hedgehog (Ihh) are expressed in endodermally derived gut epithelium, whereas their target genes are expressed in discrete layers in the gut mesenchyme [Ramalho-Santos et al., 2000; Kolterud et al., 2009]. Hh signaling is implicated in the epithelial-mesenchymal interaction to coordinate patterning and organogenesis of the gut and enteric nervous system development [Ramalho-Santos et al., 2000; Ngan et al., 2011]. In mice, loss of Shh and Ihh result in reduced muscularis propria, gut malrotation and annular pancreas. Ihh–/– mice show reduced epithelial stem cell proliferation and differentiation, accompanied by partial intestinal aganglionosis [Ramalho-Santos et al., 2000]. Ectopic expression of Ihh in small intestinal epithelium causes expansion of smooth muscle in the villus cores, indicating that Hh signaling controls the size of smooth muscle cell population in the villus cores [Kolterud et al., 2009]. Shh–/– mice display more severe phenotypes, including intestinal transformation, gastric overgrowth and duodenal stenosis. Importantly, the distal hindgut of Shh–/– mice fails to develop into alimentary and urinary tracts, resulting in a persistent cloaca, similar to the most severe form of ARM observed in humans. Gli2–/– and Gli3–/– mice also show defects in hindgut development, but the phenotypes are less severe; Gli2–/– mice develop imperforate anus, whereas Gli3–/– mice have anal stenosis and overgrowth of stomach without apparent small intestinal phenotype [Kimmel et al., 2000]. Double mutant analysis revealed that the gene dosage of Gli2 and Gli3 is crucial for hindgut development; Gli2–/–;Gli3–/–, Gli2–/–;Gli3+/–, and Gli2+/–;Gli3–/– mice all develop cloaca similar to that observed in Shh–/– mice [Mo et al., 2001]. Moreover, Ift172avc mutants also exhibit anal atresia, with discontinuity between the anal squamous epithelium and rectal columnar epithelium. These mutant mice all exhibit attenuated Hh signaling and display hindgut defects representing a full spectrum of human ARM phenotypes.

Cardiovascular Anomalies

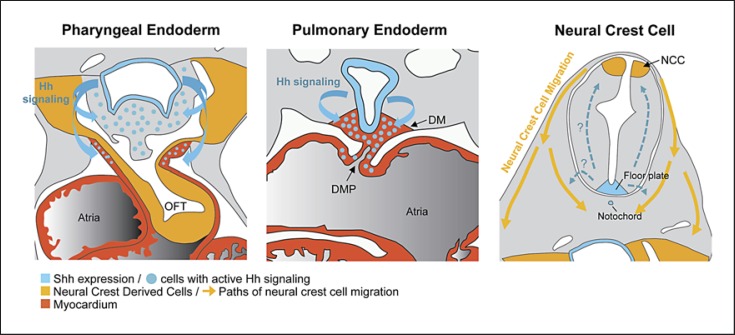

Congenital heart defects are found in up to three-quarters of individuals with VACTERL association. The most common heart defects found with VACTERL association are ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defects and tetralogy of Fallot. In addition, defects in cardiac outflow tract (OFT) and arch arteries, such as persistent truncus arteriosus, transposition of the great arteries and right aortic arch, are associated with this disorder. Importantly, all these cardiovascular anomalies are commonly present in mice with disrupted Hh signaling (i.e. Shh–/–, Gli2–/–;Gli3+/–, Ift172avc, and Ift25–/–) [Kim et al., 2001a; Washington Smoak et al., 2005; Friedland-Little et al., 2011; Keady et al., 2012]. More specifically, during early stages of cardiogenesis (E7.0–E8.0), myocardial progenitor cells receive Hh signals to promote cardiomyocyte formation [Thomas et al., 2008]. In vitro experiments have shown that primary cilia and active Hh signaling contribute to cardiomyocyte differentiation [Gianakopoulos and Skerjanc, 2005; Clement et al., 2009]. Consistent with the role of Hh signaling in left-right asymmetry, mice lacking Shh, Smo or Sufu also showed abnormal heart looping [Tsukui et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001; Cooper et al., 2005]. Between E9.0–E11.0, Shh expression in pharyngeal endoderm contributes to the development of the anterior heart field, including formation of cardiac OFT and ventricular septation, while its expression in pulmonary endoderm is required for the development of the posterior heart field, such as atrial septation [Goddeeris et al., 2007; Hoffmann et al., 2009]. For example, cell-specific deletion of Shh using Nkx2.5Cre/+ (pharyngeal/pulmonary endoderm) results in cardiac OFT defects, ventricular septal defect as well as atrial septal defects, while Shh deletion using Nkx2.1-Cre (pulmonary endoderm) leads to only atrial septal defects. Furthermore, Hh signaling is implicated in the development of cardiac neural crest cells (CNCC), which are critical for the formation of cardiac OFT and arch arteries as well as ventricular septation. Shh–/– mice have defective CNCC migration and increased cell death, whereas Shhflox/–; Nkx2.5Cre/+ mice exhibit normal CNCC migration, suggesting a direct role of Shh signaling in early CNCC development and migration [Washington Smoak et al., 2005; Goddeeris et al., 2007]. Indeed, disruption of Hh signaling in CNCC (Smoflox/–; Wnt1-Cre) cause defects in OFT and arch arteries. It will be of interest to examine whether VACTERL association is related to impaired CNCC development induced by abnormal Hh signaling. Hh signaling is also implicated in coronary artery development and maintenance in the heart [Lavine and Ornitz, 2009]. It will be intriguing to investigate whether these defects are observed in patients with VACTERL association.

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Tracheo-esophageal fistula and esophageal atresia show a close association with anorectal defects, and they are observed in about 55–70% of VACTERL patients. The oesophagus and trachea are derived from the anterior foregut tube. During gastro-respiratory development, division of the foregut results in separation of the dorsal component (esophageal) from the ventral component (tracheal). As in the developing hindgut, endodermal Hh signaling plays important roles in foregut development. Dynamic ventral-dorsal shift in Shh signaling is required for the onset of tracheo-esophageal separation and foregut morphogenesis. Spatio-temporal disruption or shift of Shh expression is frequently associated with diminished apoptosis of the lateral epithelial ridges and the failure of tracheo-esophageal separation [Ioannides et al., 2010]. In absence of Shh, mice display a spectrum of foregut malformations, including lung hypoplasia and various defects in the trachea and esophagus. Some Shh–/– mice develop less severe foregut anomalies with only esophageal and tracheal stenosis, whereas others exhibit more severe phenotypes without sub-division of the early foregut tube, leading to esophageal atresia and tracheo-esophageal fistula. The dosage effects of Hh signaling are also illustrated in Gli2–/– and Gli2–/–;Gli3+/– mice; while the foregut phenotypes of Gli2–/– mice are similar to the less severe defects of Shh–/– mice, the phenotypes of Gli2–/–;Gli3+/– mice resemble the more severe Shh–/– phenotypes. Cilia-defective mutant mice also exhibit trachea-esophageal anomalies with variable frequency. Ift172avc mutants develop esophageal stenosis with enlarged and cystic trachea. On the other hand, the foregut phenotypes of Ift25–/– mice are relatively mild; they exhibit tracheal stenosis, compression of the lungs and pulmonary isomerism but without obvious left-right asymmetry defect.

Renal Dysplasia

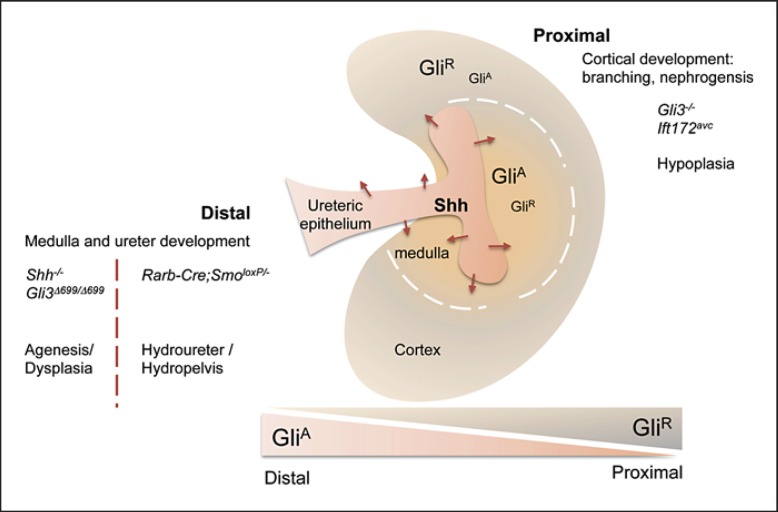

Renal defects are seen in approximately 50% of patients with incomplete formation of one or both kidneys, and/or urologic abnormalities, such as obstruction to outflow of urine or severe reflux of urine. Shh and Ihh are expressed in the developing kidney; Shh is secreted mainly from the epithelium of the presumptive ureter and medullary collecting ducts, while Ihh expression is localized to the nephrogenic tubules at the cortico-medullary border during late stages of renal development. During early kidney-urinary development, Hh pathway activity is detected within the ureteric mesenchyme, suggesting that Shh is involved in the inductive interactions between ureteric bud epithelium and metanephric mesenchyme [Yu et al., 2002]. Shh signaling establishes a tight spatial restriction of Gli2A and Gli3R in the ureter/medulla and cortex, respectively, to coordinate renal morphogenesis by controlling the expression of kidney patterning genes (Pax2, Sall1) and cell cycle modulators (CyclinD1, N-myc) [Hu et al., 2006].

Similar to the neural tube and limb, graded Gli activities are crucial for kidney patterning (fig. 2). High Hh pathway activity (high GliA and low Gli3R levels) exists in the distal ureter/medullary region, whereas high level of Gli3R is dominant in the proximal cortical domain of embryonic kidney. Mutant mice with low GliA and high GliR levels display distal/medullary anomalies. For example, Shh–/– mice develop a solitary, ectopic dysplastic kidney or bilateral renal aplasia [Mo et al., 1997]. Similarly, when Shh is specifically deleted in the ureteric lineage cells, mutant mice exhibit reduced proliferation of the ureter mesenchyme, delayed differentiation of smooth muscle in the ureter and severe hydroureter, supporting the notion that Hh pathway activation is critical for distal ureter/medullary development [Yu et al., 2002]. Importantly, Gli3R is deleterious to this process. Gli3Δ699/Δ699 mice expressing a truncated form of Gli3, which mimics the constitutive expression of Gli3R, show renal aplasia/dysplasia. Furthermore, elimination of Gli3 rescues renal morphogenesis in Shh–/– mice and restores the expression of both patterning genes and cell cycle regulators [Böse et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2006]. In a recent study, the involvement of Hh signaling in later stages of ureter morphogenesis is also established. Targeted inactivation of Smo in the intermediate mesoderm (Rarb2-Cre;SmoloxP/– mice) results in non-obstructive hydronephrosis, hydroureter and ureter peristalsis. This finding demonstrates that Hh signaling is required for the formation and/or maintenance of specific cell populations to establish unidirectional and coordinated peristalsis. Consistent with the deleterious action of Gli3R in early kidney morphogenesis, removal of Gli3 in Rarb2-Cre;SmoloxP/– mice restores normal kidney development. Therefore, the primary role for Hh signaling is likely to inhibit the formation of Gli3R in the ureteric mesenchyme [Cain et al., 2011] (fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Model for Hh signaling in the cardiovascular development. Shh produced in the pharyngeal endoderm activates cells in the anterior heart field which contribute to cardiac OFT septation. Endodermal Shh is also required for survival and proper localization within the OFT of the pharyngeal neural crest cells. In the posterior heart field, Shh from pulmonary endoderm acts on the dorsal mesocardium (DM) to form dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP), which contributes to atrial septation. In addition, Hh signaling regulates early neural crest cell migration, likely by a non-cell-autonomous repulsive effect, although the exact mechanism is unknown.

Fig. 3.

Model for Hh signaling in the developing kidney. Shh is secreted from the distal ureter epithelium and establishes a gradient of distalhigh and proximallow of Hh signal. It leads to an accumulation of GliA in ureter and medullary regions, while high concentration of GliR is localized in the cortex of the embryonic kidney. Mouse mutants bearing gain- or loss-of function mutations display unique phenotypes that segregate according to the predicted balance of GliA versus GliR. Mouse bearing gain-of-function mutation (Gli3–/–) with an absence of GliR shows cortical developmental defects. On the other hand, Hh deficiency (Shh–/–, Gli2–/–, Gli3Δ699/Δ699) leads to ureter/medullary anomalies [Cain and Rosenblum, 2011].

Unlike in the distal domain, Gli3R is required for the formation of renal cortex. Mutations leading to high GliA and low Gli3R levels cause proximal/cortical anomalies, including defects in branching morphogenesis and nephrogenesis in mice. Gli3–/– mice exhibit mild renal hypoplasia with deficiency in ureteric branching and nephrogenesis within the cortex [Cain et al., 2009]. In addition, elevated Hh pathway activity resulted from Ptch1 inactivation in the ureteric cell lineage leads to renal hypoplasia [Cain et al., 2009]. The kidney phenotypes of these Ptch1 mutants can be rescued by forced expression of Gli3R, supporting the requirement for Gli3R in proximal cortical development. Furthermore, simultaneous inactivation of Gli2 and Gli3 results in horseshoe kidney with both hydronephrosis and hydroureter [Kim et al., 2001b]. Thus, a precise balance of GliA versus GliR is critical for kidney development.

Consistent with their role in Hh signaling, primary cilia are also implicated in tubular development as well as the maintenance of normal renal morphology and function. Hypomorphic mutations in the IFT complex B produce enigmatic structural and functional kidney defects, ranging from abnormal proliferation of tubular epithelia, polycystic kidney disease to renal dysplasia with hypoplastic glomeruli as seen in Ift172avc mutants [Friedland-Little et al., 2011].

Limb Defects

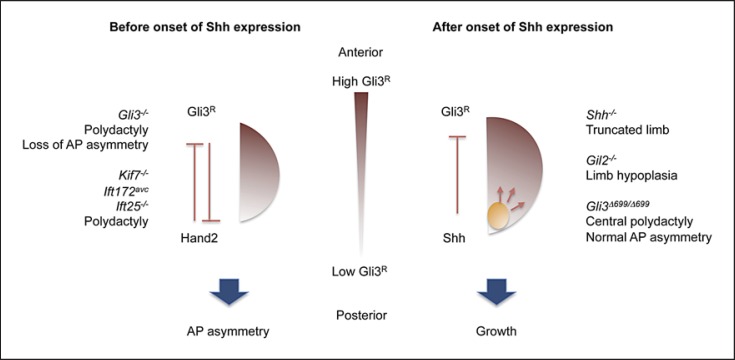

Limb defects, including absent or displaced thumbs, extra digit (polydactyly) or fusion of digits (syndactyly), occur in up to 70% of VACTERL patients. Shh is expressed in the posterior limb bud mesenchyme and acts as the principle signal of the zone of polarizing activity, which organizes anteroposterior (AP) patterning. In the developing limb bud, Gli3R exists as an anteriorhigh to posteriorlow gradient and is responsible for the establishment of polarized gene expression, including the anterior expression of Pax9 and the posterior expression of 5′Hoxd genes [te Welscher et al., 2002b; McGlinn et al., 2005]. Early limb bud acquires its AP identities independent of Shh expression. The mutual antagonism of Gli3R and Hand2, on the other hand, is the crucial mechanism for the establishment of AP limb asymmetry. Gli3 acts primarily to exclude Hand2 expression in the anterior limb bud, and Hand2 restricts Gli3 expression to the anterior limb mesenchyme. Gli3Δ699/– mutant mice with constitutive expression of a Gli3R-like activity develop limbs with AP asymmetry [Hill et al., 2009]. In contrast, loss of Gli3 in Gli3–/– and Shh–/–;Gli3–/– mice results in polydactyly and loss of AP identities [Litingtung et al., 1998; Motoyama et al., 1998; te Welscher et al., 2002a].

At later stages of limb development, Shh is expressed in the zone of polarizing activity, where Shh signaling regulates both Gli3 transcription and processing. Shh null mice show elevated Gli3R levels in the posterior limb bud, accompanied by expanded expression of Pax9 and loss of 5′Hoxd gene expression, that trigger massive apoptosis of limb mesenchyme, eventually leading to truncated limb. Therefore, the presence of Shh is required to counteract Gli3R, and appropriate levels of Gli3R allow the growth and proliferation of cartilage precursor cells. Gli3 processing in the developing limb appears to depend on IFT, as both Kif7 and cilia-defective mutants show compromised Gli3R function, leading to polydactyly [Cheung et al., 2009; Friedland-Little et al., 2011] (fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Model for Hh signaling in the developing limb. During early limb development, Shh is absent at the limb bud, the anteroposterior (AP) asymmetry is achieved by the mutual antagonism of Gli3R and Hand2 such that Gli3R exists in a gradient of anteriorhigh and posteriorlow. After onset of Shh, high level of GliA is present at the posterior end to promote the growth of cartilage precursor cells, while high concentration of GliR is localized in the anterior limb bud. Mouse mutants bearing gain- or loss-of function mutations display unique phenotypes that segregate according to the predicted balance of GliA versus GliR. Mouse bearing gain-of-function mutation (Gli3–/–, Kif7–/–, Ift172avc, Ift25–/–) with an absence of GliR shows polydactyly accompanied by loss of AP asymmetry. In contrast, Hh deficiency (Shh–/–, Gli2–/–, Gli3Δ699/Δ699) leads to limb truncation/hypoplasia or polydactyly and loss of AP asymmetry.

Downstream of Hh Signaling in VACTERL

In addition to core Hh pathway components, several Shh target genes, Forkhead and 5′Hoxd genes (Hoxd12 and Hoxd13) have also been implicated in VACTERL. Expression of Foxc2 (previously called Mfh-1) in the paraxial mesoderm depends on the notochordal Shh signal [Yamagishi et al., 2003]. Mice lacking Foxc2 exhibit interrupted aortic arch and absence of vertebral bodies as seen in Gli2 null mice [Iida et al., 1997]. Similarly, Hoxd13 expression in the limb and hindgut is regulated by Shh signaling [Roberts et al., 1995; Mandhan et al., 2006]. Hoxd13 mutant mice display limb anomalies and urogenital defects. Inactivation of Hoxd13 in mice also interrupts anal sphincter morphogenesis, while ectopic expression of Hoxd13 results in kidney agenesis [Dollé et al., 1993; Kondo et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 1998].

Together, the above studies using various Shh and Gli mutants irrefutably have improved our understanding of the molecular basis of VACTERL. Inadequate Hh pathway activity may only account for part of the VACTERL phenotypes. As highlighted in recent studies, there is a precise spatio-temporal requirement for Gli3R during patterning and organogenesis of various organ systems. Particularly in the developing limb and kidney, Gli3R play distinct roles in the distal and proximal domains of embryonic kidney, whereas Gli3R is critical for the establishment of AP asymmetry of the limb before the onset of Shh expression. Intriguingly, the severity of the VACTERL phenotypes appears to show high correlation with the balance between GliA and GliR.

Human Genetic Studies

Mutations in Hh Pathway Genes in Human Diseases

In humans, mutations in the Hh pathway genes have been associated with a board spectrum of congenital malformations as summarized in table 2. In particular, mutations in SHH and GLI3 are associated with holoprosencephaly type 3 and PHS, where ARM is included as part of the syndromic phenotypes. SHH is located on chromosome 7 (7q36). To date, a spectrum of nonsense and missense mutations, deletions and insertion in the SHH gene have been identified in the holoprosencephaly patients, and haploinsufficiency of SHH represents a cause of the disease [Belloni et al., 1996; Roessler et al., 1996; Nanni et al., 1999]. More recently, a 7q terminal deletion leading to loss of SHH gene has also been reported in a child presenting esophageal stenosis. The abnormalities of the esophagus, including atresia and stenosis, observed in this patient are strikingly similar to the foregut defects that are seen in Shh–/– mouse embryos.

Table 2.

Human mutations in HEDGEHOG pathway and related genes, associated with VACTERCL-related phenotypes

| Gene | Mutation | VACTECL related phenotypes | Diagnosis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHH |

|

esophageal stenosis, partial agenesis of sacrum, urinary tract anomalies | holoprosencephaly (HPE), microphthalmia, esophageal stenosis | Belloni et al., 1996; Nanni et al., 1999; Roessler et al., 1996; Schimmenti et al., 2003; Zen et al., 2010 |

| GLI2 | missense and loss-of-function mutations | – | holoprosencephaly (HPE) | Roessler et al., 2003 |

| GLI3 |

|

imperforate anus, polydactyly | Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS), Pallister-Hall syndrome (PHS), oral-facial-digital syndrome (OFDS) | Johnston et al., 2005 |

| KIF7 | nonsense and frameshift mutations | polydactyly, VSD | hydrolethalus syndrome (HLS), acrocallosal syndrome (ACLS), Joubert syndrome (JBTS) | Dafinger et al., 2011; Putoux et al., 2011 |

| HOXD13 | 21 bp deletion (c.163_183del) | anal atresia, bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureters, limb malformation (fusion of distal inter-phalangeal joints) | VACTERL | Garcia-Barceló et al., 2008 |

| FOXF1 | microdeletion of the FOX gene cluster16q24.1 | vertebral anomalies, gastro-intestinal atresias (esophageal, duodenal and anal), congenital heart malformation, urinary tract malformation, others (lung development defects) | intestinal malrotation, atrioventricular canal defect, renal malformation, alveolar capillary dysplasia | Stankiewicz et al., 2009 |

GLI3 is located on chromosome 7p14.1 and autosomal dominant mutations in GLI3 have been identified in patients with PHS, GCPS and oral-facial-digital syndromes. Central or postaxial polydactyly, syndactyly, imperforate anus, and other craniofacial anomalies are typical syndromic phenotypes observed in the PHS patients. Particularly, some PHS patients also exhibit lung anomalies as well as tracheo-esophageal fistula, overlapping with features in VACTERL association. Among all known PHS-associated mutations, most of them cause frameshift, RNA splicing defects or premature translation termination, resulting in the formation of a truncated GLI3 repressor protein [Kang et al., 1997; Shin et al., 1999]. By contrast, large deletions or truncation mutations in GLI3 are frequently associated with GCPS, where patients exhibit hypertelorism, macrocephaly with frontal bossing and polysyndactyly. More recently, 5 more frameshift or nonsense GLI3 mutations have been found in oral-facial-digital syndrome patients, and the location of all these mutations is adjacent to those mutations that have been reported to cause PHS [Johnston et al., 2010].

Mutations in other Hh transduction mediators, such as KIF7, are also pathogenic. Nonsense and frameshift mutations in KIF7 have recently been reported to cause hydrolethalus, acrocallosal and Joubert syndromes [Dafinger et al., 2011; Putoux et al., 2011]. Most hydrolethalus- and acrocallosal-associated mutations are clustered in the kinesin motor and coiled-coil domains of KIF7. Consistent with the roles of Kif7 in Gli trafficking and Hh signal transduction, GLI3 processing is impaired, and most GLI targets are dysregulated in acrocallosal patient fibroblasts. Joubert syndrome-related mutations are also linked to defective Hh signaling as well as instability of cilia and microtubules. Intriguingly, patients with defective KIF7 frequently present single or even multiple VACTERL-like features, such as polysyndactyly and ventricular septal defect [Dafinger et al., 2011; Putoux et al., 2011]. Thus, genes implicated in the Hh pathway cascade may represent the prime candidates for various ciliopathies as well as VACTERL association.

Genetic Contribution to VACTERL Association

The majority of VACTERL association patients appears to be sporadic, and only few instances of familial recurrence of typical VACTERL have been reported. However, an increased prevalence of single or multiple component features among first-degree relatives of VACTERL patients is observed in 10% of the cases, suggesting that some of these disorders may be inherited in a subset of patients [Solomon et al., 2010; Bartels et al., 2012]. Causality of this inheritance pattern is complex and environmental elements are likely involved.

Various mouse mutants with defective Hh signaling exhibit multiple features of the VACTERL phenotype. However, only less than 1% of patients diagnosed with VACTERL have all 6 anomalies, and more than 90% of them have 3 or fewer anomalies. To our surprise, till now, no mutation in the HH pathway genes has been found related to VACTERL association in humans. Instead, deleterious mutations in HH target genes appear to be linked to VACTERL association. The first VACTERL associated mutation has been reported in the HOXD13 gene (2q31.1) from a female patient with limb, gut and genitourinary malformations. This mutation consists of a 21 base-pair triplet repeat deletion in the exon 1 of HOXD13, resulting in the removal of 7 alanine residues from the polyalanine tract [Garcia-Barceló et al., 2008]. Similar in-frame shortening of the polyalanine tract has also been described in a large Han Chinese family with complex brachydactyly and syndactyly [Zhao et al., 2007], while other polyalanine expansion, truncation and specific amino acid substitution mutations in HOXD13 are associated with other limb malformations, including synpolydactyly 1, brachydactyly types D and E, and syndactyly type V [Goodman, 2002]. Expansions or contractions of the polyalanine tract may perturb DNA instability and is thought to be responsible for the disease manifestations. Noteworthy, anorectal or renal malformations have only been described in the patients with polyalanine contraction, but not yet in those with polyalanine expansion.

Microdeletions of another HH target gene, FOXF1 (16q24.1), are apparently related to VACTERL association. Six overlapping microdeletions, encompassing the FOX transcription factor gene cluster in chromosome 16q24.1q24.2, were identified in patients with alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins. Given that some of these patients also exhibit 3 VACTERL features, including hypoplastic left heart syndrome, renal defects and gastrointestinal atresia, FOXF1 is considered to be a risk allele common to both VACTERL association and alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins.

VACTERL-hydrocephalus (VACTERL-H) represents a subtype of VACTERL, where patients exhibit VACTERL accompanied by hydrocephalus. Unlike typical VACTERL, VACTERL-H patients manifest a distinct Mendelian inheritance pattern. Autosomal recessive and X-linked mutations in Fanconi anaemia complementation group B (FANCB) or FANCC genes are considered as the major genetic cause of VACTERL-H. In a more recent study, the potential involvement of Hh signaling in VACTERL-H is suggested by the observation that Ift172avc mutant mice develop both VACTERL and hydrocephalus phenotypes [Friedland-Little et al., 2011].

In addition to genetic alterations, environmental factors have long been suspected as risk factors for VACTERL association. This notion is supported by a recent whole-exome sequencing analysis on monozygotic twin pairs in which only one of the twins is diagnosed with VACTERL association. In this study, Solomon et al. [2011] did not find any de novo discordant exonic variants that are predicted to be pathogenic or obviously related to VACTERL association among the twins. Therefore, in this scenario, an iatrogenic environmental factor (e.g. surgical treatment) likely predisposes the patient to VACTERL association. It is also possible that the causative genetic variants may occur in the non-coding regions and that environmental factors are only responsible for increased disease susceptibility. Furthermore, it is worth considering a role for post-zygotic or somatic mutations in VACTERL association, whereby the genetic lesions are only present in the organs/tissues originated from the progenitors ‘mutated’ during embryogenesis. This would explain the discrepancy reported between monozygotic twins as well as the sporadic nature of these disorders [Rivière et al., 2012; Veltman and Brunner, 2012].

Summary and Conclusion

To date, the etiology of VACTERL association still remains largely unknown. Identification of the causative genes has been hampered by the facts that most of the cases occur sporadically and that it is due to cumulative effects of multiple genes. The heterogeneity of risk-related genetic polymorphism between individuals as well as differential environmental factors add another layer of complexity on top of these unresolved questions. Mouse models of VACTERL association recapitulate the human condition and offer a systematic genetic analysis of the etiology of VACTERL. As summarized in this review, the phenotypic spectrum of VACTERL is common to mice with defective Hh signaling and/or cilia, suggesting a central role of GliA and GliR in the etiology of VACTERL association.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. M.M. Garcia-Barceló (HKU) for her useful comments on the genetic studies. This work was supported by a research grant HKU775710 from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council to E.S.-W.N. and by operating grants from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute to C.-C.H. K.-H.K is supported by a fellowship from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

References

- Bai CB, Stephen D, Joyner AL. All mouse ventral spinal cord patterning by hedgehog is Gli dependent and involves an activator function of Gli3. Dev Cell. 2004;6:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels E, Jenetzky E, Solomon BD, Ludwig M, Schmiedeke E, et al. Inheritance of the VATER/VACTERL association. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:681–685. doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3100-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni E, Muenke M, Roessler E, Traverso G, Siegel-Bartelt J, et al. Identification of Sonic hedgehog as a candidate gene responsible for holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;14:353–356. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böse J, Grotewold L, Rüther U. Pallister-Hall syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for Gli3. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1129–1135. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain JE, Rosenblum ND. Control of mammalian kidney development by the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1365–1371. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1704-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain JE, Islam E, Haxho F, Chen L, Bridgewater D, et al. Gli3 repressor controls nephron number via regulation of Wnt11 and Ret in ureteric tip cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain JE, Islam E, Haxho F, Blake J, Rosenblum ND. Gli3 repressor controls functional development of the mouse ureter. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1199–1206. doi: 10.1172/JCI45523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung HO, Zhang X, Ribeiro A, Mo R, Makino S, et al. The kinesin protein Kif7 is a critical regulator of Gli transcription factors in mammalian hedgehog signaling. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, Young KE, Corden JL, et al. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383:407–413. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KS, Lee C, Harfe BD. Sonic hedgehog in the notochord is sufficient for patterning of the intervertebral discs. Mec Dev. 2012;129:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement CA, Kristensen SG, Møllgård K, Pazour GJ, Yoder BK, et al. The primary cilium coordinates early cardiogenesis and hedgehog signaling in cardiomyocyte differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3070–3082. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AF, Yu KP, Brueckner M, Brailey LL, Johnson L, et al. Cardiac and CNS defects in a mouse with targeted disruption of suppressor of fused. Development. 2005;132:4407–4417. doi: 10.1242/dev.02021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafinger C, Liebau MC, Elsayed SM, Hellenbroich Y, Boltshauser E, et al. Mutations in KIF7 link Joubert syndrome with Sonic Hedgehog signaling and microtubule dynamics. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2662–2667. doi: 10.1172/JCI43639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A, Mercier J, Verloes A. Child with manifestations of Nager acrofacial dysostosis, and the MURCS, VACTERL, and pulmonary agenesis associations: complex defect of blastogenesis? Am J Med Genet. 1996;62:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960301)62:1<1::AID-AJMG1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollé P, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Schimmang T, Schuhbaur B, et al. Disruption of the Hoxd-13 gene induces localized heterochrony leading to mice with neotenic limbs. Cell. 1993;75:431–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson E, Perveen R, Donnai D, Wall S, Black GC. De novo GLI3 mutation in acrocallosal syndrome: broadening the phenotypic spectrum of GLI3 defects and overlap with murine models. J Med Genet. 2002;39:804–806. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.11.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh-Yamagami S, Evangelista M, Wilson D, Wen X, Theunissen JW, et al. The mammalian Cos2 homolog Kif7 plays an essential role in modulating Hh signal transduction during development. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1320–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CM, Tessier-Lavigne M. Patterning of mammalian somites by surface ectoderm and notochord: evidence for sclerotome induction by a hedgehog homolog. Cell. 1994;79:1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland-Little JM, Hoffmann AD, Ocbina PJ, Peterson MA, Bosman JD, et al. A novel murine allele of intraflagellar transport protein 172 causes a syndrome including VACTERL-like features with hydrocephalus. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3725–3737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Barceló MM, Wong KK, Lui VC, Yuan ZW, So MT, et al. Identification of a HOXD13 mutation in a VACTERL patient. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:3181–3185. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianakopoulos PJ, Skerjanc IS. Hedgehog signaling induces cardiomyogenesis in P19 cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21022–21028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddeeris MM, Schwartz R, Klingensmith J, Meyers EN. Independent requirements for hedgehog signaling by both the anterior heart field and neural crest cells for outflow tract development. Development. 2007;134:1593–1604. doi: 10.1242/dev.02824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman FR. Limb malformations and the human HOX genes. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:256–265. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh JH, Angle B, Fox TL, Barth RF, Bendon RW, Gowans G. Developmental field defects: coming together of associations and sequences during blastogenesis. Am J Med Genet. 2002;110:320–323. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P, Götz K, Rüther U. A SHH-independent regulation of Gli3 is a significant determinant of anteroposterior patterning of the limb bud. Dev Biol. 2009;328:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AD, Peterson MA, Friedland-Little JM, Anderson SA, Moskowitz IP. Sonic hedgehog is required in pulmonary endoderm for atrial septation. Development. 2009;136:1761–1770. doi: 10.1242/dev.034157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde C, Dickinson RJ, Houtzager VM, Cullum R, Montpetit R, et al. Hippi is essential for node cilia assembly and Sonic hedgehog signaling. Dev Biol. 2006;300:523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Mo R, Bhella S, Wilson CW, Chuang PT, et al. Gli3-dependent transcriptional repression of Gli1, Gli2 and kidney patterning genes disrupts renal morphogenesis. Development. 2006;133:569–578. doi: 10.1242/dev.02220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Cilia and hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Liu A, Rakeman AS, Murcia NS, Niswander L, Anderson KV. Hedgehog signalling in the mouse requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Nature. 2003;426:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CC, Joyner AL. A mouse model of Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome: the extra-toesj mutation contains an intragenic deletion of the Gli3 gene. Nat Genet. 1993;3:241–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CC, Angers S. Gli proteins in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:513–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CC, Slusarski D, Platt KA, Holmgren R, Joyner AL. Expression of three mouse homologs of the Drosophila segment polarity gene cubitus interruptus, Gli, Gli-2, and Gli-3, in ectoderm- and mesoderm-derived tissues suggests multiple roles during postimplantation development. Dev Biol. 1994;162:402–413. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humke EW, Dorn KV, Milenkovic L, Scott MP, Rohatgi R. The output of Hedgehog signaling is controlled by the dynamic association between Suppressor of Fused and the Gli proteins. Genes Dev. 2010;24:670–682. doi: 10.1101/gad.1902910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K, Koseki H, Kakinuma H, Kato N, Mizutani-Koseki Y, et al. Essential roles of the winged helix transcription factor MFH-1 in aortic arch patterning and skeletogenesis. Development. 1997;124:4627–4638. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Lee JH, Robertson CP, Enga K, Kapur RP, Roelink H. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of soluble and membrane-tethered Sonic hedgehog by Patched-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12044–12049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220251997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides AS, Massa V, Ferraro E, Cecconi F, Spitz L, et al. Foregut separation and tracheo-oesophageal malformations: the role of tracheal outgrowth, dorso-ventral patterning and programmed cell death. Dev Biol. 2010;337:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Sweet HO, Donahue LR, Ward-Bailey P, Bronson RT, Davisson MT. A new spontaneous mouse mutation of Hoxd13 with a polyalanine expansion and phenotype similar to human synpolydactyly. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1033–1038. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Laufer E, Riddle RD, Tabin C. Ectopic expression of Sonic hedgehog alters dorsal-ventral patterning of somites. Cell. 1994;79:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JJ, Olivos-Glander I, Killoran C, Elson E, Turner JT, et al. Molecular and clinical analyses of Greig cephalopolysyndactyly and Pallister-Hall syndromes: robust phenotype prediction from the type and position of GLI3 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:609–622. doi: 10.1086/429346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JJ, Sapp JC, Turner JT, Amor D, Aftimos S, et al. Molecular analysis expands the spectrum of phenotypes associated with GLI3 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1142–1154. doi: 10.1002/humu.21328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Graham JM, Jr, Olney AH, Biesecker LG. GLI3 frameshift mutations cause autosomal dominant Pallister-Hall syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:266–268. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keady BT, Samtani R, Tobita K, Tsuchya M, San Agustin JT, et al. IFT25 links the signal-dependent movement of hedgehog components to intraflagellar transport. Dev Cell. 2012;22:940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim P, Hui CC. The VACTERL association: lessons from the Sonic hedgehog pathway. Clin Genet. 2001a;59:306–315. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.590503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PC, Mo R, Hui CC. Murine models of VACTERL syndrome: role of sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. J Pediatr Surg. 2001b;36:381–384. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel SG, Mo R, Hui CC, Kim PC. New mouse models of congenital anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(00)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolterud A, Grosse AS, Zacharias WJ, Walton KD, Kretovich KE, et al. Paracrine Hedgehog signaling in stomach and intestine: new roles for hedgehog in gastrointestinal patterning. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:618–628. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Dollé P, Zákány J, Duboule D. Function of posterior HoxD genes in the morphogenesis of the anal sphincter. Development. 1996;122:2651–2659. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume T, Deng K, Hogan BL. Murine forkhead/winged helix genes Foxc1 (Mf1) and Foxc2 (Mfh1) are required for the early organogenesis of the kidney and urinary tract. Development. 2000a;127:1387–1395. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.7.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume T, Deng K, Hogan BL. Minimal phenotype of mice homozygous for a null mutation in the forkhead/winged helix gene, Mf2. Mol Cell Biol. 2000b;20:1419–1425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1419-1425.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine KJ, Ornitz DM. Shared circuitry: developmental signaling cascades regulate both embryonic and adult coronary vasculature. Circ Res. 2009;104:159–169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem KF, Jr, He M, Ocbina PJ, Anderson KV. Mouse Kif7/Costal2 is a cilia-associated protein that regulates sonic hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13377–13382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litingtung Y, Lei L, Westphal H, Chiang C. Sonic hedgehog is essential to foregut development. Nat Genet. 1998;20:58–61. doi: 10.1038/1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Wang B, Niswander LA. Mouse intraflagellar transport proteins regulate both the activator and repressor functions of Gli transcription factors. Development. 2005;132:3103–3111. doi: 10.1242/dev.01894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandhan P, Quan QB, Beasley S, Sullivan M. Sonic hedgehog, BMP4, and Hox genes in the development of anorectal malformations in Ethylenethiourea-exposed fetal rats. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:2041–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Frías ML, Bermejo E, Rodríguez-Pinilla E. Anal atresia, vertebral, genital, and urinary tract anomalies: a primary polytopic developmental field defect identified through an epidemiological analysis of associations. Am J Med Genet. 2000;95:169–173. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001113)95:2<169::aid-ajmg15>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May SR, Ashique AM, Karlen M, Wang B, Shen Y, et al. Loss of the retrograde motor for IFT disrupts localization of Smo to cilia and prevents the expression of both activator and repressor functions of Gli. Dev Biol. 2005;287:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlinn E, van Bueren KL, Fiorenza S, Mo R, Poh AM, et al. Pax9 and Jagged1 act downstream of Gli3 in vertebrate limb development. Mech Dev. 2005;122:1218–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill P, Mo R, Fu H, Grachtchouk M, Kim PC, et al. Sonic hedgehog-dependent activation of Gli2 is essential for embryonic hair follicle development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:282–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.1038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo R, Freer AM, Zinyk DL, Crackower MA, Michaud J, et al. Specific and redundant functions of Gli2 and Gli3 zinc finger genes in skeletal patterning and development. Development. 1997;124:113–123. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo R, Kim JH, Zhang J, Chiang C, Hui CC, Kim PC. Anorectal malformations caused by defects in sonic hedgehog signaling. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:765–774. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61747-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama J, Liu J, Mo R, Ding Q, Post M, Hui CC. Essential function of Gli2 and Gli3 in the formation of lung, trachea and oesophagus. Nat Genet. 1998;20:54–57. doi: 10.1038/1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni L, Ming JE, Bocian M, Steinhaus K, Bianchi DW, et al. The mutational spectrum of the Sonic Hedgehog gene in holoprosencephaly: SHH mutations cause a significant proportion of autosomal dominant holoprosencephaly. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2479–2488. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan ES, Garcia-Barceló MM, Yip BH, Poon HC, Lau ST, et al. Hedgehog/Notch-induced premature gliogenesis represents a new disease mechanism for Hirschsprung disease in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3467–3478. doi: 10.1172/JCI43737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocbina PJ, Anderson KV. Intraflagellar transport, cilia, and mammalian hedgehog signaling: analysis in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2030–2038. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HL, Bai C, Platt KA, Matise MP, Beeghly A, et al. Mouse Gli1 mutants are viable but have defects in SHH signaling in combination with a Gli2 mutation. Development. 2000;127:1593–1605. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putoux A, Thomas S, Coene KL, Davis EE, Alanay Y, et al. KIF7 mutations cause fetal hydrolethalus and acrocallosal syndromes. Nat Genet. 2011;43:601–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna U, Wild A, Grzeschik KH, Antonarakis SE. Mutation in GLI3 in postaxial polydactyly type A. Nat Genet. 1997;17:269–271. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna U, Bornholdt D, Scott HS, Patel UC, Rossier C, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of GLI3 morphopathies includes autosomal dominant preaxial polydactyly type-IV and postaxial polydactyly type-A/B; no phenotype prediction from the position of GLI3 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:645–655. doi: 10.1086/302557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Santos M, Melton DA, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signals regulate multiple aspects of gastrointestinal development. Development. 2000;127:2763–2772. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivière JB, Mirzaa GM, O'Roak BJ, Beddaoui M, Alcantara D, et al. De novo germline and postzygotic mutations in AKT3, PIK3r2 and PIK3ca cause a spectrum of related megalencephaly syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:934–940. doi: 10.1038/ng.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DJ, Johnson RL, Burke AC, Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog is an endodermal signal inducing Bmp-4 and Hox genes during induction and regionalization of the chick hindgut. Development. 1995;121:3163–3174. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler E, Belloni E, Gaudenz K, Jay P, Berta P, et al. Mutations in the human sonic hedgehog gene cause holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;14:357–360. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler E, Du YZ, Mullor JL, Casas E, Allen WP, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the human GLI2 gene are associated with pituitary anomalies and holoprosencephaly-like features. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13424–13429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235734100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler E, Ermilov AN, Grange DK, Wang A, Grachtchouk M, et al. A previously unidentified amino-terminal domain regulates transcriptional activity of wild-type and disease-associated human GLI2. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2181–2188. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti LA, de la Cruz J, Lewis RA, Karkera JD, Manligas GS, et al. Novel mutation in sonic hedgehog in non-syndromic colobomatous microphthalmia. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;116A:215–221. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Kogerman P, Lindstrom E, Toftgárd R, Biesecker LG. GLI3 mutations in human disorders mimic Drosophila Cubitus interruptus protein functions and localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2880–2884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon BD, Pineda-Alvarez DE, Raam MS, Cummings DA. Evidence for inheritance in patients with VACTERL association. Hum Genet. 2010;127:731–733. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon BD, Pineda-Alvarez DE, Hadley DW, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Teer JK, et al. Personalized genomic medicine: lessons from the exome. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:189–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz P, Sen P, Bhatt SS, Storer M, Xia Z, et al. Genomic and genic deletions of the FOX gene cluster on 16q24.1 and inactivating mutations of FOXF1 cause alveolar capillary dysplasia and other malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Welscher P, Fernandez-Teran M, Ros MA, Zeller R. Mutual genetic antagonism involving GLI3 and dHAND prepatterns the vertebrate limb bud mesenchyme prior to SHH signaling. Genes Dev. 2002a;16:421–426. doi: 10.1101/gad.219202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Welscher P, Zuniga A, Kuijper S, Drenth T, Goedemans HJ, et al. Progression of vertebrate limb development through SHH-mediated counteraction of GLI3. Science. 2002b;298:827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1075620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teglund S, Toftgård R. Hedgehog beyond medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1805:181–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NA, Koudijs M, van Eeden FJ, Joyner AL, Yelon D. Hedgehog signaling plays a cell-autonomous role in maximizing cardiac developmental potential. Development. 2008;135:3789–3799. doi: 10.1242/dev.024083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torroja C, Gorfinkiel N, Guerrero I. Patched controls the Hedgehog gradient by endocytosis in a dynamin-dependent manner, but this internalization does not play a major role in signal transduction. Development. 2004;131:2395–2408. doi: 10.1242/dev.01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukui T, Capdevila J, Tamura K, Ruiz-Lozano P, Rodriguez-Esteban C, et al. Multiple left-right asymmetry defects in Shh–/– mutant mice unveil a convergence of the Shh and retinoic acid pathways in the control of Lefty-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11376–11381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukachinsky H, Lopez LV, Salic A. A mechanism for vertebrate Hedgehog signaling: recruitment to cilia and dissociation of SuFu-Gli protein complexes. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:415–428. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman JA, Brunner HG. De novo mutations in human genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrg3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vortkamp A, Gessler M, Grzeschik KH. Gli3 zinc-finger gene interrupted by translocations in Greig syndrome families. Nature. 1991;352:539–540. doi: 10.1038/352539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Martin JF, Bai CB. Direct and indirect requirements of Shh/Gli signaling in early pituitary development. Dev Biol. 2010;348:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington Smoak I, Byrd NA, Abu-Issa R, Goddeeris MM, Anderson R, et al. Sonic hedgehog is required for cardiac outflow tract and neural crest cell development. Dev Biol. 2005;283:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi H, Maeda J, Hu T, McAnally J, Conway SJ, et al. Tbx1 is regulated by tissue-specific forkhead proteins through a common Sonic hedgehog-responsive enhancer. Genes Dev. 2003;17:269–281. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Xie G, Fan Q, Xie J. Activation of the hedgehog-signaling pathway in human cancer and the clinical implications. Oncogene. 2010;29:469–481. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the mouse metanephric kidney. Development. 2002;129:5301–5312. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zen PR, Riegel M, Rosa RF, Pinto LL, Graziadio C, et al. Esophageal stenosis in a child presenting a de novo 7q terminal deletion. Eur J Med Genet. 2010;53:333–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Ramalho-Santos M, McMahon AP. Smoothened mutants reveal redundant roles for Shh and Ihh signaling including regulation of L/R symmetry by the mouse node. Cell. 2001;106:781–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Sun M, Zhao J, Leyva JA, Zhu H, et al. Mutations in HOXD13 underlie syndactyly type V and a novel brachydactyly-syndactyly syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:361–371. doi: 10.1086/511387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]