Abstract

Rationale

Among human adolescents, drug use is substantially influenced by the attitudes and behaviors of peers. Social factors also affect the drug-seeking behaviors of laboratory animals. Conditioned place preference (CPP) experiments indicate that social context can influence the degree to which rodents derive a rewarding experience from drugs of abuse. However, the precise manner by which social factors alter drug reward in adolescent rodents remains unknown.

Objectives

We employed the relatively asocial BALB/cJ (BALB) mouse strain and the more prosocial C57BL/6J (B6) strain to explore whether “low” or “high” motivation to be with peers influences the effects of social context on morphine CPP (MCPP).

Methods

Adolescent mice were conditioned by subcutaneous injections of morphine sulfate (0.25, 1.0, or 5.0 mg/kg). During the MCPP procedure, mice were housed in either isolation (Ih) or within a social group (Sh). Similarly, following injection, mice were conditioned either alone (Ic) or within a social group (Sc).

Results

Adolescent B6 mice expressed a robust MCPP response except when subjected to Ih-Sc, which indicates that, following isolation, mice with high levels of social motivation are less susceptible to the rewarding properties of morphine when they are conditioned in a social group. By contrast, MCPP responses of BALB mice were most sensitive to morphine conditioning when subjects experienced a change in their social environment between housing and conditioning (Ih–Sc or Sh–Ic).

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that susceptibility to morphine-induced reward in adolescent mice is moderated by a complex interaction between social context and heritable differences in social motivation.

Keywords: Addiction, Drug abuse, Environment, Opioid, Opiate, Reward, Peers, Sociability, Housing

Introduction

Social factors play an important role in adolescent susceptibility to engage in drug-seeking behavior. Drug use among peers is one of the strongest and most reliable predictors of first-time drug use (Kandel 1980) and subsequent dependence (Fergusson et al. 2008). In this regard, peer attitudes toward substance abuse are more influential as risk factors for adolescent drug use than the attitudes of parents or siblings (Needle et al. 1986). However, social bonds with family members also play a role in adolescent drug-seeking behaviors. For instance, having distant relationships with family members or one's community are well-established risk factors for drug abuse (Hamme Peterson et al. 2010). Taken as a whole, the nature and strength of various kinds of social bonds during adolescence can have a tremendous influence on the likelihood of long-term drug abuse (Bond et al. 2007).

Variations in social context can also alter the drug-seeking behaviors of rodents during adolescence, which lasts from postnatal day (PD) 21 to 60 (Laviola et al. 2003). For example, adolescent rats express a strong conditioned place preference (CPP) in response to cocaine when subjected to social isolation, but minimal preference when housed as dyads and no preference when housed in groups of three (Zakharova et al. 2009). CPP responses to drugs are also sensitive to changes in social context that occur during the conditioning phase. For instance, when conditioning of adolescent rats involves both drug exposure (cocaine or nicotine vs. saline) and a change in social context (interaction vs. isolation), only the combined experience of drug exposure and social access resulted in a CPP response (Thiel et al. 2008, 2009). Importantly, the direction of the interaction between social context and drug-seeking behavior varies with the drug that is administered. For instance, adolescent rats develop a CPP response to methylphenidate when it is given prior to social isolation, but not prior to social access (Trezza et al. 2009). Thus, in contrast to the studies of Thiel et al. (2008, 2009), the combined experience of drug exposure and social access suppressed, rather than facilitated, methylphenidate CPP responses in rats relative to individuals that were conditioned in isolation. Drug-seeking behaviors in rodents are also sensitive to whether or not social partners also receive drug treatment. For instance, late-adolescent mice exhibit enhanced CPP responses to methamphetamine if they were conditioned with a cagemate that simultaneously received the same drug treatment, but not if each mouse in the dyad received drug treatment on different conditioning days or mice were conditioned individually (Watanabe 2011). Indeed, adolescent rodents can be highly sensitive to social partners that have been previously exposed to drugs of abuse. For example, an adolescent rat will consume greater amounts of ethanol following an interaction with a social partner that has received intra-gastric ethanol injections vs. a partner that was administered with water (Hunt et al. 2001; Maldonado et al. 2008). Similarly, adolescent male mice that were not previously exposed to morphine will exhibit a heightened locomotor response to an acute morphine injection (sensitization) after repeated interactions with cagemates that received morphine treatments (Hodgson et al. 2010). In contrast, interactions with morphine-naïve cagemates effectively suppress locomotor sensitization of adolescent female mice that had previously undergone morphine treatments (Hofford et al. 2010).

Morphine has substantial effects on the social behaviors of juvenile rodents, including both suppression of social behavior (Kennedy et al. 2011) as well as facilitation (Vanderschuren et al. 1995a; Panksepp et al. 1985) depending on the dose administered as well as the age and species of test animals. However, with the exception of the sensitization experiments described above (Hodgson et al. 2010; Hofford et al. 2010), we know little about how social context influences the responses of adolescents to this drug. When tested as adults, mice that are subjected to prolonged social isolation (4 weeks) exhibit reduced morphine CPP (MCPP) responses when compared to mice that are housed with conspecifics, but a shorter duration of social isolation (2 weeks) does not change MCPP relative to socially housed controls (Coudereau et al. 1997). Influences of social context on MCPP might be explained by the responsiveness of opioid systems in the brain to social stimuli, particularly during adolescence. For instance, when juvenile rats are given access to social interactions, endogenous opioids are released within brain reward pathways (Panksepp and Bishop 1981; Vanderschuren et al. 1995b).

In mice, sensitivity to the rewarding effects of morphine can vary with the genetic background of the strain (Mogil et al. 1996; Belknap et al. 1998). Similarly, various strains of mice can derive different levels of positive affective experience from social interactions. Sociability (viz., the tendency to associate with conspecifics) varies across inbred strains of mice (Moy et al. 2004; Nadler et al. 2004; Moy et al. 2007) and has been particularly well characterized for adolescent mice of the BALB/cJ (BALB) and C57BL/6J (B6) strains (Sankoorikal et al. 2006; Panksepp et al. 2007). Adolescent B6 mice engage in more affiliative social interactions (Panksepp et al. 2007) and display less aggression (Bernard et al. 1975) than age-matched BALB mice. Importantly, social CPP experiments indicate that juvenile B6 mice prefer environments that predict access to social interactions vs. environments that have been paired with social isolation, whereas BALB mice are indifferent to these contingencies (Panksepp and Lahvis 2007). This difference in social motivation may explain the different responses of BALB and B6 mice to conspecifics that have been exposed to morphine. Adolescent B6 mice express diminished social investigation towards a social partner that has been administered with morphine, whereas BALB social behavior is not affected by the drug state of social partners (Kennedy et al. 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that genetically based differences in sociability could play a substantial role in determining whether the social environment influences morphine sensitivity during adolescence. In the present experiment, we asked whether a high degree of social motivation influences how the social environment moderates the rewarding experience of morphine. To answer this question, we manipulated the social context of adolescent BALB and B6 mice during both the housing and conditioning phases of an MCPP paradigm.

Methods and materials

Animal husbandry

Mice from the BALB and B6 strains were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and bred in our colony at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) under tightly controlled temperature (21±1°C) and humidity (40–60%). The lighting conditions were 12:12 h light/dark (dark period 0900–2100 hours). New mice were introduced to the breeding colony every 4–5 months and brother–sister mating was not conducted. Mice were housed in standard polypropylene cages (290×180×130 mm) lined with pelleted paper bedding (ECOfresh, Absorption Corp.) and had ad libitum access to chow (Lab Rodent Diet 5001, Purina Mills) and water. Pregnant females were isolated approximately 10–15 days postcoitus and pups were weaned on PD 20 and 21. Pups from available litters were combined according to strain, and test animals were randomly selected and housed in either mixed-sex (two males and two females) social groups or in isolation (see below). All experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines set forth by the institutional care and use committee at OHSU and followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Our own laboratory personnel performed postweaning animal husbandry and maintained gentle and consistent handling of mice.

MCPP procedure

The conditioning procedure began 24 h after weaning and consisted of 45-min sessions that were repeated daily over an 8-day period. All phases of the MCPP procedure, including habituation and testing, were conducted during the dark period of the LD cycle(1400–1800)under dim red illumination. Morphine conditioning involved alternating mice between a novel environment paired with morphine exposure and a novel environment paired with saline exposure. Mice were weighed and then received a 200-μl subcutaneous injection of either morphine sulfate(0.25, 1.0, or 5.0 mg/kg) orvehicle(0.9% saline). After the injection, mice were placed in an enclosed peripheral compartment (318 × 152 × 152 mm) of a three-compartment testing apparatus (ABS Plastics, Midland Plastic Inc., New Berlin, WI, USA) that contained either a “paper” or “aspen” conditioning environment. The “paper” environment consisted of soft paper bedding (Cellu-Dri Soft, Shepherd Specialty Papers, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) and two smooth schedule 40 1-in. PVC couplers, while the “aspen” environment consisted of aspen wood shavings (Nepco, Northeastern Products Corporation, Warrens-burg, NY, USA) and two threaded schedule 40 1-in. PVC couplers (for additional details, see Panksepp and Lahvis 2007). Fresh bedding was used for each conditioning session and PVC couplers were washed with detergent and rinsed prior to each use. To evaluate whether there was a natural preference for either of the novel environments, additional groups of BALB and B6 mice were exposed to the aspen and paper environments, except that they received saline prior to being placed in each of the conditioning environments (i.e., saline–saline control groups). Testing occurred on PD 29/30, 24 h after the final conditioning session (see below).

Social variables

Mice were housed as a social group (Sh) or housed in social isolation (Ih). The social environment was also manipulated during the 45-min conditioning sessions. Mice experienced morphine/saline conditioning either as a social group (Sc) or as isolated individuals (Ic). Mice that were conditioned as a social group were placed together into the conditioning environment during both saline and morphine conditioning sessions. The composition of these groups remained consistent throughout the experiment and each mouse within a group always received the same morphine dose. In total, four housing/conditioning combinations were utilized (see Table 1). Throughout the experiments, group compositions remained the same for mice that were exposed to a social housing or conditioning context (i.e., Sh–Ic, Ih–Sc, or Sh–Sc). Furthermore, mice that were housed within a social group and conditioned in separate chambers (i.e., Sh–Ic) were conditioned on the same morphine–saline schedule and at the same time of day. The order of conditioning (morphine treatment on day 1 vs. day 2) and morphine dose were pseudorandomized and counterbalanced for mice from each strain and housing/conditioning combination.

Table 1.

Experimental groups formed using combinations of social grouping or isolation during the housing and conditioning phases of the MCPP paradigm

| Designation | Housing environment | Conditioning environment |

|---|---|---|

| Sh–Sc | Social | Social |

| Sh–Ic | Social | Isolate |

| Ih–Ic | Isolate | Isolate |

| Ih–Sc | Isolate | Social |

Habituation and MCPP testing

On days 7 and 8 of the conditioning procedure, all mice were individually habituated for 20 min to the testing apparatus. During habituation, mice had access to the peripheral compartments via circular openings (51 mm diameter), but the compartments did not contain either set of the conditioning cues (bedding and PVC couplers). Prior to testing, the aspen conditioning environment was assembled in one of the peripheral compartments and the paper environment was assembled in the other peripheral compartment. Mice were tested individually 24 h after the final conditioning session (PD 29/30) and did not receive a morphine or saline injection prior to the test. Mice were placed into the central chamber (“Lexan” plastic floor) of the testing apparatus with free access to the two peripheral compartments. The testing apparatus was then covered with a transparent Plexiglas top and mouse movement between compartments was videotaped (3CCD digital camcorder, Sony, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min. The video recordings of each test were stored on a desktop computer (Precision T3400, Dell, Round Rock, TX, USA) and analyzed for the total duration of time spent in each compartment using computer-assisted analysis software (ButtonBox v.5.0, Behavioral Research Solutions, Madison, WI, USA). Preference scores were calculated as the difference between the duration spent in the environment associated with morphine sulfate treatment and the environment associated with saline treatment. Approximately one third of the videos were scored in duplicate with one rater blind to the morphine sulfate dose and social treatment. Inter-rater reliability was strong (rP's≥0.98, degrees of freedom (df)=87).

Mice that exhibited very low levels of exploratory behavior during testing were excluded from the statistical analyses. Mice were considered “inactive” when at the onset of testing they remained in a peripheral compartment for >15 min before entering the other peripheral compartment. These individuals constituted <6% of all MCPP tests. Inactivity was only observed in BALB mice, but no bias was found for sex, housing/conditioning combination, or dose of morphine sulfate. Furthermore, inactive BALB mice were equally likely to spend >15 min in the compartment containing the saline-paired bedding or the morphine-paired bedding.

MCPP scores were derived from assessments of 6–10 mice per strain for each housing/conditioning combination at each morphine dose. Saline–saline controls were conducted on 10–14 mice per strain for each housing/conditioning combination. Thus, the total sample size for this study consisted of 273 MCPP tests.

Statistical analysis

The preference scores of control mice were assessed using a two-sided t test (HØ=0) (Fig. 1). The effects of morphine dose on MCPP responses of mice from each strain were assessed using 2×4 analyses of variance (ANOVA) with morphine dose and sex as between-subjects factors (Fig. 2). A 3×2×2×2 ANOVA, excluding bedding preference data from saline control groups, was conducted for each strain to evaluate the interaction between sex, morphine dose, and social contexts of housing and conditioning (Fig. 3). Additional one-way ANOVAs were conducted separately for BALB and B6 mice from different social housing/conditioning combinations that also included the preference scores of control mice (Fig. 4). These analyses were used to examine the effects of each morphine dose on MCPP scores for a specific housing/conditioning combination. Orthogonal contrasts were used for all post hoc comparisons. For all statistical tests, P<0.05 was considered significant.

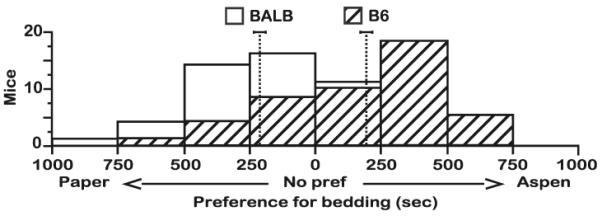

Fig. 1.

Natural preferences of BALB and B6 mice for the conditioning environments. Control mice were subjected to the same procedure as experimental mice, but both of the conditioning environments were paired with saline administration. Both BALB and B6 control mice expressed a natural preference for the conditioning environments. B6 control mice preferred the aspen environment over paper, while BALB control mice preferred the paper environment over aspen. N=46 mice per strain. Dotted vertical lines denote the respective mean for each distribution as reported in the Results section. Data are presented as the total number of mice within each range of preference scores

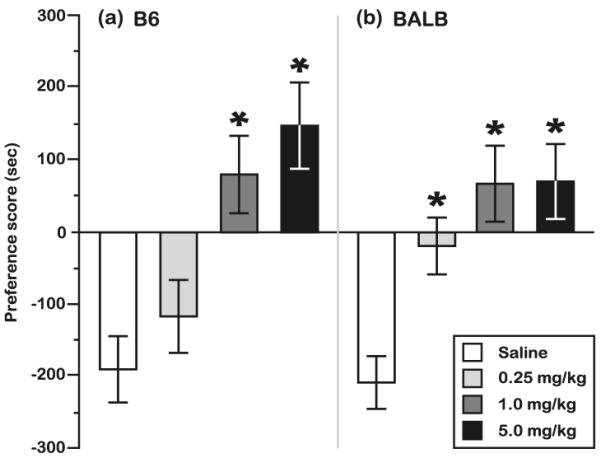

Fig. 2.

MCPP responses of B6 and BALB mice at each dose of morphine. Mice from both the a B6 and b BALB strains developed a preference for the environment paired with the 1.0- and 5.0-mg/kg morphine sulfate doses relative to the preferences of control mice, but only BALB mice expressed a significant preference for the 0.25-mg/kg morphine sulfate dose. *P<0.05, orthogonal contrast with saline. Morphine, N=27–32 mice for each combination of dose and strain; saline, N=46 mice per strain. All data are presented as the mean preference score±standard error of the mean

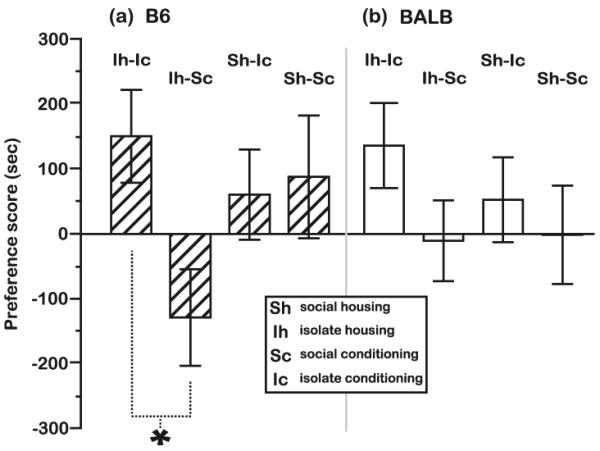

Fig. 3.

MCPP responses of B6 and BALB mice as a function of each housing/conditioning combination. When all morphine doses were combined, MCPP responses of a B6 but not b BALB mice were sensitive to the social environment of housing and conditioning. B6 mice from the Ih–Sc condition expressed a reduced preference for the morphine-paired bedding relative to mice in the Ih–Ic condition, while no difference in preference was observed in BALB mice from different social housing/conditioning groups. *P<0.05, orthogonal contrast. Morphine, N=19–24 mice for each combination of housing/conditioning social environment and strain. All data are presented as the mean preference score±standard error of the mean

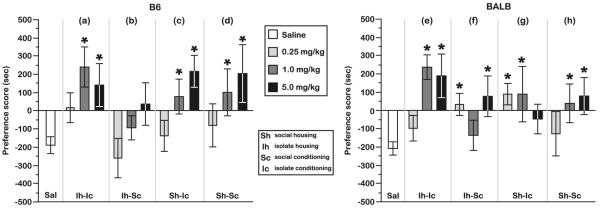

Fig. 4.

MCPP responses of BALB and B6 mice from each housing/conditioning combination as a function of morphine dose. B6 mice from the a Ih–Ic, c Sh–Ic, and d Sh–Sc housing/conditioning combinations expressed increasing preferences for higher morphine doses. However, B6 mice in the b Ih–Sc condition did not develop a significant CPP for any morphine dose. The MCPP responses of BALB mice were more varied between different housing/conditioning combinations. f, g When the housing/conditioning combination involved a transition between social grouping and isolation (Ih–Sc or Sh–IC), BALB mice exhibited an MCPP for 0.25-mg/kg morphine that was not observed. e, h when the social environment was stable (Ih–Ic or Sh–Sc). BALB mice from both the Ih–Sc and Sh–Ic conditions did not develop MCPP at 1.0- and 5.0-mg/kg morphine, respectively, but these doses elicited an MCPP response in Ih–Ic and Sh–Sc mice. *P<0.05, orthogonal contrast with saline. Ns morphine=6–10 mice per strain for each housing/conditioning and morphine dose; saline=46 mice per strain. All data are presented as the mean preference score ± standard error of the mean

Results

Natural preferences for conditioning environments

To determine whether mice from either strain expressed a natural preference for the conditioning environments, individuals were alternately exposed to the paper and aspen environments, always receiving saline injections prior to being placed into a conditioning environment. Both BALB and B6 mice expressed a natural preference, but for different conditioning environments (Fig. 1). B6 mice preferred the aspen bedding (t=4.1, df=45, P<0.0005; mean aspen preference±SEM=189.8±46 s), whereas BALB mice from the control group preferred the paper bedding (t=5.7, df=45, P<0.0001; mean paper preference±SEM=208.1±37 s). This strain-dependent bedding preference was highly stable, irrespective of sex (BALB F[1, 40]=0.004, P=NS; B6 F[1, 41]=0.1, P=NS) and the social context in which mice were housed (BALB F[1, 40]=1, P=NS; B6 F[1, 41]=2, P=NS) or conditioned (BALB F[1, 40]=1.4, P=NS; B6 F[1, 41]=2.1, P=NS). Thus, we pooled the preference scores of control animals from each housing/conditioning combination (Sh–Ic, Ih–Ic, Sh–Sc, and Ih–Sc) to establish a baseline preference score for each strain.

Overall morphine preference

When evaluating whether the time spent in the preferred bedding (paper for BALB, aspen for B6) was affected by morphine conditioning, there was a subtle, but significant effect for both strains (effect of morphine, F[1, 177]=8.27, P<0.005). By contrast, when morphine administration was paired with the environments that saline–saline control mice did not prefer, there was a substantial reversal in the preferences of mice from both strains toward the morphine-paired bedding (effect of morphine, F[1, 258]=34, P<0.0001), an expected phenomenon that has been previously observed in CPP studies (for review, see Cunningham et al. 2011). The sex of the test mice did not influence morphine CPP regardless of whether mice received morphine treatment in preferred or nonpreferred bedding (sex×morphine interaction, preferred bedding F[1, 177]=0.7, P=NS; non-preferred bedding F[1, 258]=0.7, P=NS). Since BALB and B6 mice expressed a natural preference for different conditioning environments, statistical tests were conducted separately for each strain. Moreover, to evaluate the effects of morphine dose and the housing/conditioning contexts on MCPP, additional analyses were conducted within the context of a biased design, which focused specifically on mice that were administered morphine during exposure to the nonpreferred bedding (aspen for BALB, paper for B6). Thus, the preference scores for control mice are presented as the time spent in the nonpreferred bedding minus the time spent in the preferred bedding, whereas preference scores for experimental mice are presented as the time spent in the morphine-paired (originally nonpreferred) bedding minus the time spent in the saline-paired (originally preferred) bedding. In this biased design, morphine conditioning elicits a CPP response in which mice are drawn away from their preferred bedding and toward the morphine-paired bedding. Biased designs can result in a “false CPP response” if the drug used for conditioning is anxiolytic and reduces aversion toward the nonpreferred bedding (Tzschentke 1998). However, as mentioned above, mice from both strains developed a CPP response even when morphine was paired with the preferred bedding, which suggests that a CPP response to morphine is not solely due to the anxiolytic properties of morphine. Although mice from both strains developed MCPP in the preferred bedding, the effect of morphine administration on bedding preference was much weaker compared with the CPP responses of mice for which morphine was paired with the nonpreferred bedding (preferred r2=0.039, F[1, 177]=8.27, P<0.005; nonpreferred r2=0.13, F[1, 258]=34, P< 0.0001). Due to the less robust CPP response of mice conditioned to morphine in the preferred bedding, there was no effect of social context of housing and conditioning, whereas there was a significant effect of social context if mice were conditioned to morphine in the nonpreferred bedding.

MCPP dose–response

During MCPP testing, both BALB and B6 mice exhibited a preference for the bedding that had previously been paired with morphine exposure (effect of morphine, B6 F[3, 129]=8.8, P<0.0001; BALB F[3, 123]=8.9, P<0.0001), although the specific morphine doses that engendered a preference were different for each strain. For example, both BALB and B6 mice developed a preference for the bedding that was paired with administration of 1.0- or 5.0-mg/kg morphine (Fig. 2; orthogonal contrasts, control vs. 1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg, respectively; B6 1.0 mg/kg F[1, 125]=11.2, P<0.005; 5.0 mg/kg F[1, 125]=20.2, P<0.0005; BALB 1.0 mg/kg F[1, 119]=19.2, P<0.0005; 5.0 mg/kg F[1, 119]=17.9, P< 0.0005). However, only BALB mice exhibited a CPP response for 0.25-mg/kg morphine (control vs. 0.25 mg/kg, B6 F[1, 125]=0.4, P=NS; BALB F[1, 119]=8.8, P<0.005). Sex did not influence the effects of morphine dose on the CPP responses of either B6 (F[3, 129]=0.5, P=NS) or BALB (F[3, 123]=0.5, P=NS) test mice.

Effects of social context on MCPP in B6 mice

The morphine preferences of B6 mice were not independently affected by the social context of either the housing environment (F[1, 91]=0.7, P=NS) or the conditioning environment (F[1, 91]=2.7, P=NS), but there was an interaction between these variables (Fig. 3a; social housing×social conditioning interaction, F[1, 91]=4.1, P<0.05). When mice were housed in a social context (Sh), the MCPP responses of B6 mice were not responsive to the social context of the conditioning environment (orthogonal contrast, Sh–Sc vs. Sh–Ic, F[1, 69]=0.1, P=NS). However, when B6 mice were housed in social isolation (Ih), the conditioning environment had a substantial effect on MCPP (orthogonal contrast, Ih–Sc vs. Ih–Ic, F[1, 69]=6.3, P<0.05). Mice housed individually and conditioned in a social group (Ih–Sc) did not exhibit an MCPP response, in contrast to the B6 response in all other social treatments (orthogonal contrast, Ih–Sc vs. all other groups, F[1, 69]=6.3, P<0.05; mean preference score±SEM Ih–Sc=−107±62 s; all other groups combined=83.1±65.4 s). Furthermore, the MCPP response of the Ih–Sc group did not differ from the bedding preference expressed by B6 controls (Fig. 4b; orthogonal contrast, Ih–Sc vs. control, 0.25 mg/kg F[1, 65]=0.37, P=NS; 1.0 mg/kg F[1, 65]=0.44, P=NS). It should be noted that the Ih–Sc group exhibited a trend toward MCPP at the highest dose (Ih–Sc vs. control, 5.0 mg/kg F[1, 65]=3.7, P=0.06). In general, the effects of social context on the CPP responses of B6 mice were not influenced by the sex of test mice (social housing×social conditioning×sex interaction, F[1, 91]=1.7, P=NS). However, there was an interaction between sex and social conditioning context (F[1, 91]=4.3, P<0.05) as well as a three-way interaction between sex, social housing context, and morphine dose (F[2, 90]=4.3, P<0.05).

Overall, the adolescent B6 Sh–Sc, Sh–Ic, and Ih–Ic groups all exhibited a significant CPP response to the 1.0-and 5.0-mg/kg morphine dose, but not to the 0.25-mg/kg dose. Despite the trend towards a morphine preference at the 5.0-mg/kg dose, Ih–Sc mice from the B6 background did not develop a significant CPP response to any dose of morphine (Fig. 4a–d).

Effects of social context on MCPP in BALB mice

Similar to the MCPP responses of B6 mice, BALB responses to morphine were not independently affected by the social context of either the housing environment (F[1, 86]=0.1, P=NS) or the conditioning environment (F[1, 86]=2.9, P=NS). We also did not find an interaction effect between the social contexts of housing and conditioning on the MCPP responses of BALB mice (F[1, 86]=0.1, P=NS). However, an effect on the MCPP responses of BALB mice was observed when we considered the interaction between the social contexts experienced during housing and conditioning and the specific dose of morphine that was administered (Fig. 4e–g; social housing×social conditioning×morphine dose interaction, F[2, 85]=3.4, P<0.05). Most notably, adolescent BALB responses were sensitive to the lowest morphine dose (0.25 mg/kg) when there was a change in social context between the housing and conditioning phases of the MCPP procedure (i.e., Ih–Sc and Sh–Ic) (Fig. 4f, g; orthogonal contrast, control vs. 0.25, Ih–Sc F[1, 66]=6.4, P<0.05; Sh–Ic F[1, 63]=9.6, P<0.005). BALB mice were not sensitive to the lowest dose of morphine when they were maintained continuously in isolation (Ih–Ic) or within a social group (Sh–Sc) (Fig. 4e, h; control vs. 0.25 mg/kg, Ih–Ic F[1, 66]=1.4, P=NS; Sh–Sc F[1, 61]=0.5, P=NS).

At intermediate and high doses of morphine, BALB mice continuously exposed to social isolation (Ih–Ic) or social grouping (Sh–Sc) exhibited MCPP (orthogonal contrasts, control vs. 1.0 mg/kg, Ih–Ic F[1, 66]=14.2, P<0.0005; Sh–Sc F[1, 61]=5.6, P<0.05; control vs. 5.0 mg/kg, Ih–Ic F[1, 66]=27.6, P<0.0001; Sh–Sc F[1, 63]0.7, P<0.05). Furthermore, BALB mice from the Ih–Ic group expressed the strongest MCPP responses to these morphine doses relative to all other BALB mice (orthogonal contrast, Ih–Ic vs. mice from other social contexts (1.0- and 5.0-mg/kg morphine), F[1, 118]=6.8, P<0.05).

Interestingly, adolescent BALB mice that were maintained within the same social context throughout housing and conditioning expressed a dose–response relationship in which increasing doses of morphine resulted in increased CPP responses. However, this relationship was lost when mice were alternated between different housing and conditioning social contexts. BALB mice that were maintained within a social group during housing and then transferred into isolation during conditioning (Sh–Ic) exhibited a CPP response to the intermediate morphine dose (orthogonal contrast, control vs. 1.0 mg/kg, F[1, 63]=7.5, P<0.01), but not the high morphine dose (control vs. 5.0 mg/kg, F[1, 63]=2.5, P=NS). In contrast, no clear dose–response relationship was found in mice that were housed in isolation and conditioned within a social group (Ih–Sc), which exhibited a response to the high morphine dose (orthogonal contrast, control vs. 5.0 mg/kg, F[1, 66]=9.0, P<0.005), but not to the intermediate dose (control vs. 1.0 mg/kg, F[1, 66]=0.6, P=NS). The effects of social context on the CPP responses of BALB mice were not influenced by sex of the test mice (social housing×social conditioning×morphine dose×sex interaction, F[2, 85]=0.8, P=NS).

Discussion

During adolescence, social relationships with both caregivers and peers are among the most important determining factors of drug abuse (Needle et al. 1986; Bond et al. 2007; Hamme Peterson et al. 2010). In this study, we attempted to model the effects of the social environment on drug-seeking behavior in adolescent rodents. Consistent with previous studies, social context had significant effects on the morphine preferences of adolescent mice, but only when the social contexts of both housing and conditioning were considered together rather than as independent factors. In addition, the morphine preferences of BALB and B6 mice were differentially affected by social context during the CPP procedure, indicating a possible role for social motivation in moderating how social variables influence drug-seeking behaviors.

We hypothesized that the MCPP responses of adolescent B6 mice would be particularly sensitive to the social context of housing and conditioning. Unexpectedly, the MCPP responses of B6 mice from three of the four experimental groups (Ih–Ic, Sh–Ic, and Sh–Sc) were indistinguishable, expressing significant preferences at higher morphine doses, but not at the lowest morphine dose (0.25 mg/kg). Only B6 mice from the Ih–Sc experimental group were different as they failed to express MCPP in response to all morphine doses. We suggest three possible explanations for the unique B6 MCPP response to Ih–Sc conditioning.

One possible explanation for the lack of an MCPP response by B6 mice from the Ih–Sc group is that access to social interactions (after housing in social isolation) provides a positive affective experience in the saline environment that serves as an alternative to morphine reward. Adolescent B6 mice experience social reward because they express social CPP following 24 h of social isolation (Panksepp and Lahvis 2007). Operationally, then, the lack of an observable MCPP response in B6 mice from the Ih–Sc group could be due to the independent acquisition of a social CPP in one conditioning environment and morphine CPP in the alternate environment. In support of this interpretation, adolescent BALB mice do not express social CPP responses (Panksepp and Lahvis 2007) and BALB mice show a robust morphine CPP response in the Ih–Sc condition. The interpretation that social interaction mediates a rewarding experience is also supported by physiological data. Access to social opportunities promotes the release of endogenous opioids in the adolescent rat brain (Vanderschuren et al. 1995b).

In contrast to Ih–Sc mice, B6 mice from the Sh–Sc experimental group exhibited a clear CPP response to morphine. One possible explanation for the differential expression of MCPP between these groups is that isolate housing alters the expression of social behavior during conditioning. Such a possibility would be consistent with a previous study that demonstrated social CPP responses in B6 mice require a period of social isolation prior to testing (Panksepp and Lahvis 2007). Moreover, adolescent B6 mice that have been isolated for 24 h spend more time investigating a social partner compared to mice that have been isolated for 15 min (Panksepp et al. 2008). Thus, we expect that B6 mice in the Ih–Sc experimental group exhibited higher levels of approach towards social partners during conditioning than mice from the Sh–Sc condition. Future studies exploring the influence of social context on drug-seeking behavior would benefit from including a measure of social behavior during the conditioning phase of the experiment.

A second possible explanation is that the adolescent B6 mice are less capable of learning to distinguish between environments that are associated with morphine vs. saline when they are conditioned within a highly rewarding (and thus highly stimulating) social context. In this scenario, attention to social interactions could effectively reduce the difference in incentive salience between the conditioning environments, such that B6 mice do not learn the morphine-bedding association.

A third, less likely, possibility is that B6 mice from the Ih–Sc condition did not express a preference for the morphine-paired bedding because these mice were conditioned in a social group, but tested individually. For B6 mice, the transition from an isolate context to a social context is a highly salient experience that predicts a 50% likelihood of morphine reward. In the Ih–Sc experimental group, social isolation, also highly salient for B6 mice, would predict a 0% chance of morphine reward. Thus, when mice are tested in isolation after having previously experienced morphine in a social context, the lack of cagemates may diminish the salience of the morphine-paired environment, resulting in reduced expression of MCPP.

An additional and exciting consideration is that the Ih–Sc experience for B6 mice involves changes in how mice of this experimental group experience social interactions. Specifically, morphine exposure can suppress social investigation by adolescent mice (Kennedy et al. 2011), which might diminish the quality of social interaction and thus reduce social reward. Consistent with this explanation, treatment of adolescent rats with another psychoactive drug, methylphenidate, both depresses play behavior (Vanderschuren et al. 2008) and diminishes expression of social CPP, irrespective of whether the drug was administered to the subject rat, its social partner, or both individuals (Trezza et al. 2009). As this process occurs, social cues may become a contextual predictor of morphine exposure (50% chance, see above). This would be consistent with a study which shows that B6 subjects exposed to morphine in the presence of an object mouse and then to saline in the presence of a different mouse show a greater tendency for social approach toward the morphine-paired object mouse (Borlongan and Watanabe 1994). This finding suggests that, with repeated morphine exposure, the social reward that is derived from interactions with a social partner is replaced by a different value for the social partner, its value as a contextual cue that predicts morphine reward. The reduced MCPP response of B6 mice within the Ih–Sc condition might represent the pathology of social withdrawal that accompanies substance abuse during adolescence in which the rewarding aspects of one's social community are replaced by valuation of peers that supply drugs of abuse. If morphine administration prior to a social interaction can alter the quality of the interaction enough to suppress social reward, then perhaps the abnormal social behavior of a morphine-treated social partner during conditioning becomes more strongly associated with morphine administration for the test mouse (100% chance) than the presence of a social partner alone (50% chance). In this scenario, B6 mice from the Ih–Sc experimental group would only express MCPP if tested in the presence of social partners that had received morphine treatment prior to testing.

We did not expect that the morphine-seeking behaviors of BALB mice would be highly sensitive to social context. However, BALB mice that experienced a change in social environment between housing and conditioning (i.e., Sh–Ic and Ih–Sc) expressed MCPP responses to even the lowest dose of morphine (0.25-mg/kg morphine sulfate). In these two experimental groups, MCPP was diminished at one or the other “high” doses of morphine. The results for BALB mice in the Ih–Sc condition are consistent with the finding that adolescent BALB/cByJIco mice housed in social groups and conditioned in isolation can be intolerant to higher doses of morphine (Belzung and Barreau 2000). By contrast, when the social context did not change across the housing and conditioning phase experiments (i.e., Sh–Sc and Ih–Ic), BALB mice were insensitive to the lowest dose of morphine, but expressed a robust MCPP to higher morphine doses. One possible explanation for this finding is that the expression of MCPP is influenced by the stress that BALB mice experience when undergoing transitions between social isolation and social contact. BALB mice display a heightened sensitivity to general stressors consistent with “trait anxiety” (Belzung and Griebel 2001). For example, adolescent BALB mice express heightened anxiety-like behavior in the open field test compared with the albino variant of the B6 strain (Mason et al. 2009). Moreover, plasma corticosterone levels increase in adult BALB mice, but not B6 mice, when they are transferred from a social to isolate housing environment and vice versa (Scislowska-Czarnecka et al. 2004). Morphine treatment can increase the percentage of time a rat spends in the open arms of an elevated plus maze, which suggests that morphine can induce anxiolysis in rodents (Zarrindast et al. 2005). Thus, one possibility is that low doses of morphine can directly reduce the anxiety resulting from changes in social context. Alternatively, social stress may enhance the sensitivity of BALB mice to the rewarding properties of morphine. For example, stress, including social stressors, can facilitate self-administration of drugs of abuse that do not have anxiolytic properties, such as cocaine or amphetamine (Piazza and Le Moal 1998; Caprioli et al. 2007).

During adolescence, social bonds with both peers and caregivers are important in determining the susceptibility to engage in drug use (Bond et al. 2007). The use of a CPP paradigm combined with precise manipulations of the social environment provides an opportunity to study the mechanisms by which reward systems interact with the neural circuitries of the social brain. Previous CPP studies have primarily focused on the influences of either social isolation during housing or the addition of a social partner during conditioning on drug-seeking behavior. However, the findings presented here demonstrate that the MCPP responses of adolescent mice are not determined solely by the social context of housing or drug exposure per se, but by an interaction between these social variables. Furthermore, previous studies have not addressed the possibility that the effects of social context on drug use may be mediated by individual differences in social motivation. Here, we show for the first time that the influence of social context on MCPP responses differed between the prosocial B6 strain and the relatively asocial BALB strain. Taken together, these results suggest that morphine reward in adolescent mice is dependent upon a complex interaction between social context, social motivation, and strength of the morphine dose.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Caitlin Jackowski, Nora Moore, Lisa Stedman-Falls, and Vanessa Jimenez for their important contributions to this project. This work was funded by a NIDA research grant (R01DA022543).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Belknap JK, Riggan J, Cross S, Young ER, Gallaher EJ, Crabbe JC. Genetic determinants of morphine activity and thermal responses in 15 inbred mouse strains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:353–360. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Barreau S. Differences in drug-induced place conditioning between BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:419–423. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Griebel G. Measuring normal and pathological anxiety-like behaviour in mice: a review. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard BK, Finkelstein ER, Everett GM. Alterations in mouse aggressive behavior and brain monoamine dynamics as a function of age. Physiol Behav. 1975;15:731–736. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Butler H, Thomas L, Carlin J, Glover S, Bowes G, Patton G. Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:357.e9–357.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan CV, Watanabe S. Failure to discriminate conspecifics in amygdaloid-lesioned mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:677–680. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli D, Celentano M, Paolone G, Badiani A. Modeling the role of environment in addiction. Progress in NeuroPsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2007;31:1639–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudereau JP, Debray M, Monier C, Bourre J-M, Frances H. Isolation impairs place preference conditioning to morphine but not aversive learning in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1997;130:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s002130050218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Groblewski PA, Voorhees CM. Place conditioning. In: Olmstead MC, editor. Neuromethods: animal models of drug addiction. vol 53. Springer NY: 2011. pp. 167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamme Peterson C, Buser TJ, Westburg NG. Effects of familial attachment, social support, involvement, and self-esteem on youth substance use and sexual risk taking. Fam J. 2010;18:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson SR, Hofford RS, Roberts KW, Wellman PJ, Eitan S. Socially induced morphine pseudosensitization in adolescent mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:112–120. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328337be25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofford RS, Roberts KW, Wellman PJ, Eitan S. Social influences on morphine sensitization in adolescent females. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PS, Holloway JL, Scordalakes EM. Social interaction with an intoxicated sibling can result in increased intake of ethanol by periadolescent rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;38:101–109. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(200103)38:2<101::aid-dev1002>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Drug and drinking behavior among youth. Annu Rev Sociol. 1980;6:235–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BC, Panksepp JB, Wong JC, Krause EJ, Lahvis GP. Age-dependent and strain-dependent influences of morphine on mouse social investigation behavior. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:147–159. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328343d7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Macrì S, Morley-Fletcher S, Adriani W. Risk-taking behavior in adolescent mice: psychobiological determinants and early epigenetic influence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado AM, Finkbeiner LM, Kirstein CL. Social interaction and partner familiarity differentially alter voluntary ethanol intake in adolescent male and female rats. Alcohol. 2008;42:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SS, Baker KB, Davis KW, Pogorelov VM, Malbari MM, Ritter R, Wray SP, Gerhardt B, Lanthorn TH, Savelieva KV. Differential sensitivity to SSRI and tricyclic antidepressants in juvenile and adult mice of three strains. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Kest B, Sadowski B, Belknap JK. Differential genetic mediation of sensitivity to morphine in genetic models of opiate antinociception: influence of nociceptive assay. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:532–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy S, Nadler J, Perez A, Barbaro R, Johns J, Magnuson T, Piven J, Crawley J. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:287–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, Barbaro JR, Wilson LM, Threadgill DW, Lauder JM, Magnuson TR, Crawley JN. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler J, Moy S, Dold G, Trang D, Simmons N, Perez A, Young N, Barbaro R, Piven J, Magnuson T, Crawley J. Automated apparatus for quantitation of social approach behaviors in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, McCubbin H, Wilson M, Reineck R, Lazar A, Mederer H. Interpersonal influences in adolescent drug use—the role of older siblings, parents, and peers. Subst Use Misuse. 1986;21:739–766. doi: 10.3109/10826088609027390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Bishop P. An autoradiographic map of (3H) diprenorphine binding in rat brain: effects of social interaction. Brain Res Bull. 1981;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(81)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Jalowiec J, DeEskinazi FG, Bishop P. Opiates and play dominance in juvenile rats. Behav Neurosci. 1985;99:441–453. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp JB, Jochman K, Kim JU, Koy JJ, Wilson ED, Chen Q, Wilson CR, Lahvis GP. Affiliative behavior, ultrasonic communication and social reward are influenced by genetic variation in adolescent mice. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(4):e351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000351. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp JB, Lahvis GP. Social reward among juvenile mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:661–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp JB, Wong JC, Kennedy BC, Lahvis GP. Differential entrainment of a social rhythm in adolescent mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankoorikal GM, Kaercher KA, Boon CJ, Lee JK, Brodkin ES. A mouse model system for genetic analysis of sociability: C57BL/6J versus BALB/cJ inbred mouse strains. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scislowska-Czarnecka A, Chadzinska M, Pierzchala-Koziec K, Plytycz B. Long-lasting effects of social stress on peritoneal inflammation in some strains of mice. Folia Biol (Krakow) 2004;52:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel K, Sanabria F, Neisewander J. Synergistic interaction between nicotine and social rewards in adolescent male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:391–402. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Okun AC, Neisewander JL. Social reward-conditioned place preference: a model revealing an interaction between cocaine and social context rewards in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Conditioned place preference induced by social play behavior: parametrics, extinction, reinstatement and disruption by methylphenidate. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference paradigm: a comprehensive review of drug effects, recent progress and new issues. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:613–672. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Niesink RJ, Spruijt BM, Van Ree JM. Effects of morphine on different aspects of social play in juvenile rats. Psychopharmacology. 1995a;117:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02245191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Stein EA, Wiegant VM, Van Ree JM. Social play alters regional brain opioid receptor binding in juvenile rats. Brain Res. 1995b;680:148–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00256-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Trezza V, Griffioen-Roose S, Schiepers OJG, Van Leeuwen N, De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer ANM. Methylphenidate disrupts social play behavior in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2946–2956. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S. Drug-social interactions in the reinforcing property of methamphetamine in mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:203–206. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328345c815. doi:210.1097/FBP.1090b1013e328345c328815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova E, Miller J, Unterwald E, Wade D, Izenwasser S. Social and physical environment alter cocaine conditioned place preference and dopaminergic markers in adolescent male rats. Neuroscience. 2009;163:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast M-R, Rostami P, Zarei M, Roohbakhsh A. Intracerebroventricular effects of histaminergic agents on morphine-induced anxiolysis in the elevated plus-maze in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;97:276–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]