Abstract

Background

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS, Kayexalate) has been implicated in the development of intestinal necrosis. Sorbitol, added as a cathartic agent, may be primarily responsible. Previous studies have documented bowel necrosis primarily in postoperative, dialysis, and transplant patients. We sought to identify additional clinical characteristics among patients with probable SPS-induced intestinal necrosis.

Methods

Rhode Island Hospital surgical pathology records were reviewed to identify all gastrointestinal specimens reported as containing SPS crystals from December 1998 to June 2007. Patient demographics, medical comorbidities, and hospital courses of histologically verified cases of intestinal necrosis were extracted from the medical records.

Results

Twenty-nine patients with reports of SPS crystals were identified. Nine cases were excluded as incidental findings with normal mucosa. Nine patients were excluded as their symptoms began before SPS administration or because an alternate etiology for bowel ischemia was identified. Eleven patients had confirmed intestinal necrosis and a temporal relationship with SPS administration suggestive of SPS-induced necrosis. Only 2 patients were postoperative, and only 4 had end-stage renal disease (ESRD). All patients had documented hyperkalemia, received oral SPS, and developed symptoms of intestinal injury between 3 hours and 11 days after SPS administration. Four patients died.

Conclusion

Intestinal ischemia is a recognized risk of SPS in sorbitol. Our series highlights that patients may be susceptible even in the absence of ESRD, surgical intervention, or significant comorbidity.

Keywords: cation exchange resins, hyperkalemia, ischemic colitis, kidney failure

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS, Kayexalate) administered in sorbitol is a recognized, although infrequently reported, cause of intestinal necrosis. SPS, a cation-exchange resin, is given to patients with hyperkalemia as a means of binding and excreting potassium through the gastrointestinal tract. When administered orally, SPS releases sodium ions in the acidic stomach, binds hydrogen ions, and subsequently exchanges hydrogen for potassium in the small and large intestine.1 Exchange resins were first synthesized in 1935, first described as a treatment in medical patients in 1961, and approved for use in the United States in 1975.1,2 In its early use, SPS was administered as a suspension in water; however, concerns of constipation and fecal impaction led to the common practice of administering SPS with hypertonic sorbitol, a cathartic agent.2 Sorbitol, rather than SPS resin itself, has been implicated in the development of intestinal injury.

Twenty-four cases of intestinal necrosis secondary to SPS in sorbitol have been reported to date, initially in the renal transplant literature.1,3–14 The vast majority of these cases occurred postoperatively; in the critically ill, in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and in those with uremia. This entity has been infrequently described in less-ill and/or nonsurgical patients.

The goal of this study was to identify patients from our institution with probable SPS-induced intestinal necrosis in an effort to further describe their medical comorbidities, potential predisposing conditions, and clinical outcomes.

Methods

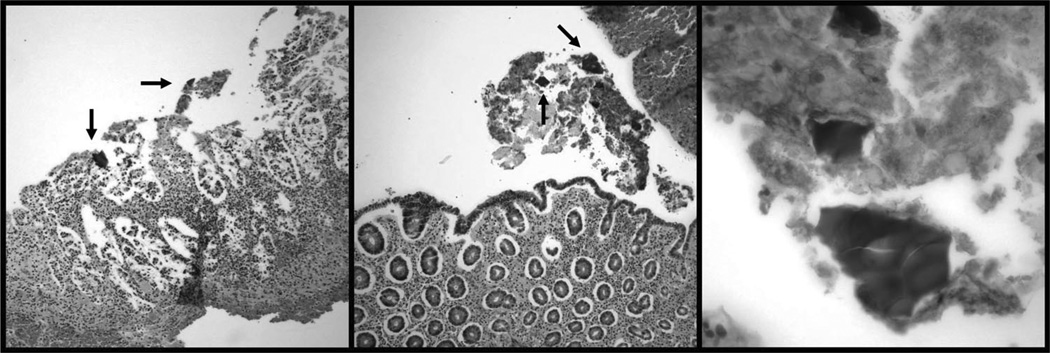

We conducted a retrospective chart review with the approval of the institutional review board and in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The surgical pathology database at Rhode Island Hospital was searched to identify all specimens containing SPS crystals between December 1998 and June 2007. SPS crystals were identified based on their rhomboid, basophilic appearance, mosaic pattern, and adherence to surface epithelium (Fig.).15 These reports were reviewed by an expert pathologist to identify cases of true mucosal injury and intestinal necrosis. Cases with normal mucosa, in which SPS crystals were an incidental finding, were excluded. Patients whose symptoms of intestinal ischemia developed prior to SPS administration were also excluded. Patients with potential alternate causes of intestinal ischemia (eg, infectious colitis or mesenteric ischemia) were excluded as the exact role of SPS-sorbitol in relation to these other factors could not be determined. Charts were then reviewed to ascertain patient demographics, medical comorbidities, hospital courses, and clinical outcomes for all patients with confirmed SPS-induced intestinal injury.

Fig.

Histopathological Findings. Left: Ischemic and necrotic epithelium with SPS crystals (arrows) (H&E orig. mag. ×20); Center: Ischemic mucosa with epithelial attenuation, atrophy, and SPS crystals (arrows) (H&E orig. mag. ×20); Right: SPS fragments (H&E orig. mag. ×60).

Results

Twenty-nine patients with reports of SPS crystals in surgical pathology specimens were identified. Of these, a total of 9 patients were excluded as incidental SPS crystals in a background of normal intestinal mucosa. Three patients were excluded as their symptoms of intestinal ischemia began prior to SPS administration (range: 3–14 days). An additional 6 patients had conditions which are known to cause intestinal ischemia and were therefore excluded from the analysis (Table 1).16–19

Table 1.

Patients excluded due to alternate etiologya

| Pt. | Age | Diagnosis | Course | Outcome | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | Clostridium difficile colitis | Diarrhea, pancolitis, C. difficile toxin positive. SPS administered on admission | Total colectomy | Pseudomembranous colitis |

| 2 | 58 | Mesenteric ischemia | 1 wk abdominal pain + rectal bleeding; SPS administered on admission | MRA confirmed IMA stenosis. Inferior mesenteric artery stented | Colonoscopy: mucosal fibrinoinflammatory exudates and mucosal necrosis |

| 3 | 64 | AAA repair/intra-operative hypotension | Intraoperative hypotension complicating AAA repair, dusky bowel noted; SPS administered postoperatively | Sigmoid resection postoperative day 1 | Transmural necrosis |

| 4 | 32 | Bowel obstruction | Admitted with bowel obstruction, administered SPS at presentation | Hemicolectomy; intestinal ischemia secondary to obstruction | Mucosal transmural necrosis; omental fat necrosis with chronic inflammation |

| 5 | 88 | C. difficile colitis | 1 wk of diarrhea, abdominal pain after antibiotics. Administered SPS on admission. Septic | Colonoscopy. Medically treated for C. difficileinfection | Pseudomembranous colitis |

| 6 | 73 | Rectovaginal fistula | Rectal bleeding × 2 d, given SPS on admission | Sigmoid resection: rectovaginal fistula w/surrounding inflammation | Dense serosal adhesions, chronic transmural inflammation and focal transmural necrosis |

AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; SPS, sodium polystyrene sulfonate; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; IMA, inferior mesenteric artery.

Of 29 patients, 11 were identified with confirmed intestinal ischemia and a temporal relationship with SPS-sorbitol administration that was suggestive of SPS-induced intestinal necrosis (Table 2). Histopathologic findings ranged from focal ulceration to transmural necrosis (Table 3). Only 2 patients were admitted for surgical procedures, both orthopaedic (knee replacement and hip fracture). The most common admission diagnoses were pneumonia and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Mean age was 70.8 (range: 30–91) with a female predominance (9/11 = 81.8%). Only 4 out of 11 patients (36%) had ESRD requiring hemodialysis. Three patients presented with hyper-kalemia despite normal renal function. The majority of patients had hypertension and coronary artery disease. A minority had diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and COPD. The average potassium level was 6.4 mEq/L (range: 5.5– 8.3), treated with a mean SPS dose of 92 g (range: 30–170 g). Only 2 patients had symptoms of uremia and/or associated EKG changes. All patients received oral SPS. In 2 patients, the dosage of SPS was not recorded.

Table 2.

Patient demographics, comorbidities, interventions, and outcomesa

| Case | Age (yr), sex |

Comorbidities | Admission diagnosis |

Potassium (mEq/L)b |

SPS dose (g) |

Time to symptoms (d)c |

Patient expired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62 M | ESRD, CAD, HTN | Rectal bleeding | 7.3 | 170 | <1 | N |

| 2 | 83 F | CAD, HTN, dyslipidemia, COPD | Chest pain | 5.8 | 120 | 2 | Y |

| 3 | 63 F | CAD, HTN, DM2, dyslipidemia, hypothyroid, pancreatitis | Pancreatitis | 6.5 | 120 | 1 | N |

| 4 | 78 F | CAD, HTN, ESRD, atrial fibrillation, hypothyroid | Pelvic fracture | 6.5 | 60 | <1 | N |

| 5 | 83 M | CAD, HTN, dyslipidemia, CHF, COPD | COPD | 6.8 | 135 | 2 | Y |

| 6 | 75 F | CAD, HTN, dyslipidemia, DM2, CKD | Pneumonia | 5.5 | 60 | 3 | N |

| 7 | 30 F | ESRD, lupus nephritis | Depression | 8.3 | 90 | <1 | Y |

| 8 | 91 F | HTN, CKD | Pneumonia | 6.1 | 30 | 5 | N |

| 9 | 85 F | HTN, COPD | COPD | 5.7 | 45 | 3 | Y |

| 10 | 59 F | HTN, CKD, gout, adrenal insufficiency | Knee replacement | 5.9 | N/A | 11 | N |

| 11 | 70 F | ESRD, HTN, DM2 | Rectal bleeding | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM2, diabetes mellitus, type 2; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; N/A, not available; HTN, hypertension; SPS, sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

Serum potassium at time of SPS administration.

Time to intestinal symptoms after first SPS dose.

Table 3.

Histopathologic findings in affected patients

| Case | Histopathologic findings | Intervention | Intestinal involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Colonic mucosa with mild acute inflammation, focal ulceration, and granulation tissue | Colonoscopy | Right colon, splenic flexure |

| 2 | Hemorrhagic and hyperemic mucosa with focal transmural necrosis and fibrinoinflammatory exudates | Colectomy | Pancolonic |

| 3 | Ulcerated mucosa with fibrinoinflammatory exudates and focal necrosis | Colonoscopy | Right colon |

| 4 | Mucosa with acute colitis and fibrinopurulent exudates | Colonoscopy | Sigmoid colon, rectum |

| 5 | Transmural necrosis, perforation, and acute and chronic serositis | Small bowel resection | Small bowel |

| 6 | Focal necrosis and necroinflammatory exudates | Colonoscopy | Right colon |

| 7 | Diffuse transmural necrosis | Colectomy | Pancolonic |

| 8 | Ulcerated colonic mucosa with reactive epithelial changes | Colonoscopy | Rectum |

| 9 | Mucosal necrosis with necroinflammatory exudates | Colonoscopy | Left colon |

| 10 | Segmental ischemic necrosis, focally transmural, with evidence of perforation. Supportive serositis | Colectomy | Small intestine; right and transverse colon |

| 11 | Necrotic mucosa and fibrinopurulent debris | Colonoscopy | Right colon |

The most common symptoms indicating intestinal ischemia were abdominal pain (9 patients), distension (5 patients), and gastrointestinal bleeding (4 patients). Symptoms began between 3 hours to 11 days after SPS administration. Ischemia mainly affected the colon (10 patients) with 1 patient demonstrating isolated small bowel injury. Distribution in the colon was variable, including isolated right, left, and pancolonic involvement. Overall mortality in our series was 36%.

Discussion

Intestinal necrosis is a recognized complication of SPS administered in sorbitol, with significant morbidity and mortality. Incidence of SPS-mediated intestinal injury has been estimated as 0.27% to 1.8%.3,7 Recognition of this entity at our institution prompted our retrospective investigation into clinical characteristics that affected patients might have in common. To our knowledge, our study involves the largest series of patients with intestinal necrosis suspected to be secondary to SPS in sorbitol. Review of our case series revealed several unexpected and unique findings.

First, the majority of our patients were admitted with medical diagnoses, with only 2 patients undergoing surgical procedures prior to SPS administration. This is in marked contrast to prior reports, which described this entity primarily in postoperative patients.1,3–14 We also document that a minority of affected patients had end-stage renal disease (ESRD), again in contrast to prior reports. ESRD may predispose patients to intestinal necrosis through changes in blood volume during dialysis, hyperreninemia, elevated prostaglandin production, and localized colonic mesenteric vasospasm. 1,3,7 Renal transplant patients may be further susceptible due to chronic immunosuppressive therapy.6,20 Likewise, delayed intestinal transit in postoperative patients, due to ileus or opiate use, slows SPS transit leading to increased risk of mucosal injury.3 Our series highlights that patients need not have ESRD or significant surgical interventions to be susceptible to SPS-induced necrosis. Furthermore, the severity of illness in these patients at the time of admission was generally low. In particular, patients 2, 5, and 9 had few comorbidities, were admitted for noncritical illnesses, and expired as a result of intestinal injury. This suggests that non-postoperative patients and patients without significant vascular compromise are potentially at risk for this complication. Overall mortality was found to be 36% in our series, which is consistent with previous reports.1,3–14

Given the severity of intestinal complications, the therapeutic role of SPS needs to be re-evaluated. One gram of SPS possesses a theoretical in-vitro exchange capacity of 2 to 3.1 mEq of potassium and an in vivo capacity of approximately 1 mEq.21 Early clinical studies demonstrated the potential of SPS resin to lower potassium; however, results may have been confounded by the patients’ low potassium, high glucose diet, as well as the use of other potassium-lowering agents (insulin, bicarbonate).22,23 Subsequent studies have questioned the effectiveness of SPS resin. In vivo potassium binding capacity may be lower than previously estimated, on the order of 0.4 to 0.8 mEq per gram of SPS.24 Additionally, some of the potassium bound by SPS resin is likely already destined for excretion through the bowel. Further, cathartics used with SPS may produce a degree of extracellular volume contraction, acidosis, and may subsequently elevate serum potassium.25 Gruy-Kapral et al25 studied the effects of single-dose SPS resin on serum potassium levels and failed to demonstrate a decrease below pretreatment values. Similar findings have been documented in neonates.26

Second, our series also highlights the questionable use of SPS resin in certain clinical circumstances. Several patients in our series received SPS despite normal renal function, when diuretics alone may have succeeded in lowering serum potassium levels. One such patient subsequently expired. Furthermore, patients with ESRD with intact hemodialysis access were given substantial doses of SPS resin, when dialysis would have offered definitive therapy. In cases where more rapid reduction is warranted, alternative means should be considered, such as intravenous calcium, insulin, bicarbonate, and inhaled beta-adrenergic agonists.26 SPS resin has a slow onset of action, on the order of hours to days, contraindicating its use as sole therapy for life-threatening hyperkalemia.27,28

Finally, if SPS resin is utilized, the addition of sorbitol should be avoided. The role of sorbitol as the cause of mucosal injury has been previously outlined. Lillemoe et al compared the effects of SPS alone, SPS in sorbitol, and sorbitol alone in both uremic and nonuremic rats. Only those rats that received sorbitol (either alone or with SPS) developed histologic intestinal changes and associated morbidity. SPS alone did not cause intestinal injury.4 It is believed that the hyperosmotic load of sorbitol may directly damage intestinal mucosa, cause vasospasm of the intestinal vasculature, and exacerbate inflammation through elevated prostaglandin levels.11,12,29 The resulting histopathologic changes vary from patchy mucosal ulcerations to pseudomembranes and transmural necrosis, all findings characteristic of ischemic bowel, but with an absence of large vessel disease.7,8,13 Given the preponderance of evidence implicating sorbitol in clinically significant intestinal necrosis, alternate vehicles for SPS should be considered. Proposed examples include water, syrup, milk, lactulose, and SPS brownies.13,30

Future studies are needed to determine the safety of SPS administered in alternative vehicles. Additionally, dosing studies may ascertain whether there exists a threshold of SPS-sorbitol administration above which intestinal injury is more likely to develop. The major limitation of our study is its retrospective, observational nature, as well as its small sample size. Additionally, excluding patients with a potential alternate etiology for intestinal ischemia may have underestimated the risk of SPS in our series. However, while SPS administration may have contributed to intestinal necrosis in these patients, the timeframe and presence of alternate conditions argues against a major role of SPS-sorbitol in these cases. Finally, without a control group we are unable to make conclusions regarding a positive association between SPS use and intestinal necrosis. Nevertheless, our case series demonstrates that patients without previously hypothesized risk factors may remain susceptible to this entity, a finding in contrast to prior investigations. Further studies are needed to examine the absolute strength of association between SPSsorbitol and intestinal ischemia.

Conclusion

SPS in sorbitol has been implicated in the development of intestinal necrosis, primarily mediated by the sorbitol component. Previous studies documented these findings almost exclusively in postoperative, renal transplant, and critically ill patients. Our study highlights that all patients are potentially susceptible, including those without previously described comorbidities. The indications for SPS resin use, as well as alternative vehicles for its delivery, should be re-evaluated. SPS-induced intestinal ischemia remains an under recognized, easily avoided complication, associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Physicians who routinely use this agent in sorbitol should be aware of its life-threatening complications.

Key Points.

Intestinal ischemia is a recognized risk of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS, Kayexalate) in sorbitol, with significant associated morbidity and mortality.

Patients may be susceptible to intestinal injury even in the absence of previously hypothesized risk factors.

When treating hyperkalemia, alternative means of potassium reduction should be considered.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mark Legolvan, MD, from the Department of Pathology at Rhode Island Hospital, for his assistance in preparing the histopathology images for this publication.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures, conflicts of interest, proprietary interests, or financial support to report.

References

- 1.Dardik A, Moesinger RC, Efron G, et al. Acute abdomen with colonic necrosis induced by Kayexalate-sorbitol. South Med J. 2000;93:511–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham SC, Bhagavan BS, Lee LA, et al. Upper gastrointestinal tract injury in patients receiving kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) in sorbitol: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:637–644. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerstman BB, Kirkman R, Platt R. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:159–161. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lillemoe KD, Romolo JL, Hamilton SR, et al. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery. 1987;101:267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott TR, Graham SM, Schweitzer EJ, et al. Colonic necrosis following sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate)-sorbitol enema in a renal transplant patient. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:607–609. doi: 10.1007/BF02049870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wootton FT, Rhodes DF, Lee WM, et al. Colonic necrosis with Kayexalate-sorbitol enemas after renal transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:947–949. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-11-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashid A, Hamilton SR. Necrosis of the gastrointestinal tract in uremic patients as a result of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) in sorbitol: an underrecognized condition. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:60–69. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelsey PB, Chen S, Lauwers GY. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 37–2003. A 79-year-old man with coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, end-stage renal disease, and abdominal pain and distention. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2147–2155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc030031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers FB, Li SC. Acute colonic necrosis associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) enemas in a critically ill patient: case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 2001;51:395–397. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng ES, Stringer KM, Pegg SP. Colonic necrosis and perforation following oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Resonium A/Kayexalate) in a burn patient. Burns. 2002;28:189–190. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatelain D, Brevet M, Manaouil D, et al. Rectal stenosis caused by foreign body reaction to sodium polystyrene sulfonate crystals (Kayexalate) Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shioya T, Yoshino M, Ogata M, et al. Successful treatment of a colonic ulcer penetrating the urinary bladder caused by the administration of calcium polystyrene sulfonate and sorbitol. J Nippon Med Sch. 2007;74:359–363. doi: 10.1272/jnms.74.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy-Chaudhury P, Meisels IS, Freedman S, et al. Combined gastric and ileocecal toxicity (serpiginous ulcers) after oral kayexalate in sorbital therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:120–122. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett LN, Myers TF, Lambert GH. Cecal perforation associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate-sorbitol enemas in a 650 gram infant with hyperkalemia. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13:167–170. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parfitt JR, Driman DK. Pathological effects of drugs on the gastrointestinal tract: a review. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price AB, Davies DR. Pseudomembranous colitis. J Clin Pathol. 1977;30:1–12. doi: 10.1136/jcp.30.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitsudo S, Brandt LJ. Pathology of intestinal ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 1992;72:43–63. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabaroudis A, Papaziogas B, Koutelidakis I, et al. Disruption of the small intestinal mucosal barrier after intestinal occlusion: a study with light and electron microscopy. J Invest Surg. 2003;16:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brewster DC, Franklin DP, Cambria RP, et al. Intestinal ischemia complicating abdominal aortic surgery. Surgery. 1991;109:447–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arvanitakis C, Malek G, Uehling D, et al. Colonic complications after renal transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1973;64:533–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berlyne GM, Janabi K, Shaw AB. Dangers of resonium A in the treatment of hyperkalemia in renal failure. Lancet. 1966;1:167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)90697-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111–115. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196101192640302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherr L, Ogden DA, Mead AW, et al. Management of hyperkalemia with a cation-exchange resin. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:115–119. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196101192640303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emmett M, Hootkins RE, Fine KD, et al. Effect of three laxatives and a cation exchange resin on fecal sodium and potassium excretion. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:752–760. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruy-Kapral C, Emmett M, Santa Ana CA, et al. Effect of single dose resin-cathartic therapy on serum potassium concentration in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1924–1930. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9101924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noerr B. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) Neonatal Netw. 1993;12:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.AMA Drug Evaluations. ed 6. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1986. AMA Department of Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziessman HA. Alkalosis and seizure due to a cation exchange resin and magnesium hydroxide. South Med J. 1976;69:497–499. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197604000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zijlstra FJ. Sorbitol, prostaglandins, and ulcerative colitis enemas. Lancet. 1981;2:815–816. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson K, Gardner ME. Kayexalate candy. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1978;35:1034–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]