Abstract

Schistosomula, the larval stage of schistosomes in vertebrate hosts, are highly vulnerable and considered an ideal target for vaccine and drug development. Although the schistosomule stage is essential for biological studies, collecting sufficient numbers of schistosomula from their definitive hosts in vivo is difficult to accomplish. However, in vitro collection via cercariae transformation can effectively yield high numbers of schistosomula. We compared a current and widely used double-ended–needle mechanical transformation method to a culture medium based on a nonmechanical method. We found the rates of transformed cercariae, i.e., separated cercariae heads from tails, differed by only 2–7% at 0.5, 1, and 2 days in culture and that there was no significant difference in the number of transformed cercariae between the transformation methods at 3 and 4 days in culture. Notably, the mechanical and nonmechanical cercariae transformation methods both yielded significantly large and similar quantities of viable schistosomula. Given that the nonmechanical method is simpler and less damaging to the parasites, we recommend the use of it as an alternative way for in vitro cercariae transformation. In addition, we also observed morphological changes of the detached cercariae tails in culture medium. Interestingly, the tails are able to regenerate head-like organs/tissues and survive for at least 4 days. This intriguing change suggests unique biological features of the cells in the tails.

Several species of Schistosoma are the causative agents of schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease afflicting more than 200 million people worldwide (Steinmann et al., 2006; King, 2010). Schistosome parasites have a complex life cycle with free-swimming aquatic stages (miracidia) that infect intermediate molluscan hosts, prior to infecting their definitive vertebrate host. Infectious cercariae are released from the snail and swim in fresh water before penetrating the skin of their definitive host, where they transform into schistosomula after the loss of their tail. The schistosomula migrate through several tissue layers and organs and reach the liver, where male and female worms become mature, pair up, and copulate. Paired worms move to the gut or bladder wall (according to species; for details, see http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/html/schistosomiasis.htm) and the females begin production of eggs (Gryseels et al., 2006). These eggs are ultimately shed via the definitive host’s feces or urine, and miracidia then emerge from the eggs.

For more than 30 yr, praziquantel (PZQ) has been the only available treatment for schistosomiasis. Considerable efforts have been made to develop alternative therapies such as vaccines and novel drugs. Different developmental stages of the schistosome life cycle are targeted, such as schistosomules and adult worms. The schistosomule is an ideal target for vaccine and drug development, not only because this stage is highly vulnerable (Damian, 1987), but also because large quantities of parasites can be easily obtained in vitro (Abdulla et al., 2009; Peak et al., 2010). To acquire parasites at this immensely important parasitic stage in vitro, many nonmechanical and mechanical methods have been developed and compared (Ramalho-Pinto et al., 1974; Salafsky et al., 1988; Hammouda et al., 1994; Gobert et al., 2007). In the case of nonmechanical methods, they include the incubation of cercariae in chemicals, and sera and/or serum-free media (Ramalho-Pinto et al., 1974). However, many media are no longer used, and most of them are not practicable for obtaining schistosomula for in vitro studies. Three mechanical methods have been employed for the acquisition of schistosomules, including centrifugation, vortexing, or pressure shearing, such as using the 21-gauge–needle method (Colley and Wikel, 1974; Ramalho-Pinto et al., 1974). Recently, the double-ended–needle method that presumably was developed from the normal needle process has been the most widely used for cercariae transformation in vitro (Colley and Wikel, 1974; Mann et al., 2010; Milligan and Jolly, 2011). For example, double-ended–needle transformed schistosomula have been recently employed in microarray studies (Parker-Manuel et al., 2011), investigations on gene function (Bhardwaj et al., 2011), inquiries that utilize RNA interference (Stefanić et al., 2010), and for drug discovery (Manneck et al., 2011). Although the double-ended–needle mechanical transformation method can have a wide array of applications, there are several problems associated with it, including heightened parasite contamination, an increased risk of infection to the researchers handling the parasites, and increased parasite damage among the mechanically transformed schistosomula (Salafasky et al., 1988).

In the present study, we sought to compare the effectiveness of cercariae transformation using the mechanical transformation double-ended–needle method and a nonmechanical transformation method in which cercariae heads and tails separate naturally in a culture medium. In conjunction with this latter work, we have also observed striking morphological changes among the detached cercariae tails, an intriguing phenomenon that has not been reported previously.

Biomphalaria glabrata snails (M-line) infected with Schistosoma mansoni (NIH-SM-PR1) were maintained as described by Loker and Hertel (1987). Schistosoma mansoni cercariae were shed from infectious snails at 7 wk postinfection by exposure to light for approximately 90 min at room temperature (RT) in artificial spring water (ASW).

Cercariae were placed in petri dishes at RT to allow particulate waste matter to settle. The cercariae were then transferred to 2 50-ml conical tubes. The tubes were inverted and allowed to sit for 10 min at RT. The supernatant (containing the cercariae) was transferred to a new 50-ml conical tube for further debris removal. The cercariae were then placed on ice and left to settle in the dark for 45 min (Milligan and Jolly, 2011). The ASW was removed and the cercariae were washed twice with enriched RPMI (eRPMI) medium, RPMI 1640 (containing L-glutamine; Invitrogen, New York, New York) with antibiotics (150 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin; GIBCO, New York, New York), and 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (GIBCO).

Mechanical transformation of cercariae into schistosomula was performed according to Milligan and Jolly (2011) by passing the parasites between 2 10-ml syringes joined by a 22-gauge double-ended, luer lok emulsifying needle (Scientific Commodities Incorporated, Lake Havasu, Arizona) 20 times. Nonmechanical transformation of cercariae into schistosomules was accomplished by leaving the cercariae undisturbed in eRPMI. Both groups of parasites were evenly separated into 12-well culture dishes (Nunc Multidish, Rochester, New York) filled with eRPMI supplemented with 5% CO2, and placed in a water-jacketed incubator for 4 days at 37 C.

In the nonmechanical method, the culture dishes were gently agitated to obtain an even distribution of schistosomes in the wells for optimal visualization. Five randomly chosen wells cultured according to each method were chosen for observation. Parasites were examined by counting the number of whole-bodied cercariae and separated cercariae heads using a Discovery V8 Stereo Zeiss dissecting scope. These observations were made at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days.

To determine whether the transformed cercariae were dead, they were stained with 2.0 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI, Invitrogen) (544 nm excitation/620 nm emission) for approximately 20 min (Peak et al., 2010) and visualized at ×100 magnification with the use of a Zeiss Axioskop 2 Plus Mot Plus microscope equipped with a rhodamine filter and a halogen light source. To find whether the cells from the detached tails were alive, they were stained with 0.5 μg/ml fluorescein diacetate (FDA, an esterase substrate) (485 nm excitation/520 nm emission) (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) for approximately 5 min (Peak et al., 2010) and visualized as described above, but with an FITC filter. A high-resolution microscopy camera, AxioCam HRc, was used to photograph the schistosomes. For comparative analysis, parasites in all experiments were considered viable, with <50% parasite surface area fluorescing. This criterion was set based on 2 considerations: (1) many dead cells may not stain well and (2) some cells may appear to still be alive when the entire organism is actually dead. Viable parasites were counted from 2 new randomly selected wells from both culture methods at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days.

Additionally, movement of cercariae tails after separation from heads was further examined and photographed, and cercariae were counted with the use of a dissecting scope (previously noted) at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days. Tails were considered moving if there was some form of visible motion in a time frame of 10 sec.

At 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days, anywhere from 39–346 and 46–380 transformed cercariae were observed in a field of view that comprised a total range of 750–2,300 and 260–803 transformed cercariae for each time point of the cercariae separation and viability studies, respectively. At 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days, approximately 31–89 cercariae tails were examined in a field of view consisting of a total number of 140–284 cercariae tails at each time point for the morphology and movement studies. At each time point, the mean percent separated cercariae, viable schistosomules, and cercariae tail movement was enumerated. Two-tailed homoscedastic Student’s t-tests were performed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) to determine if there was a difference in the percent of transformed cercariae (separated heads) between the mechanical and nonmechanical transformation methods, if there was a difference in the percent of viable schistosomula between the 2 methods, and if there was a difference in the percent of moving tails between the 2 methods. Data were considered significantly different if P < 0.05.

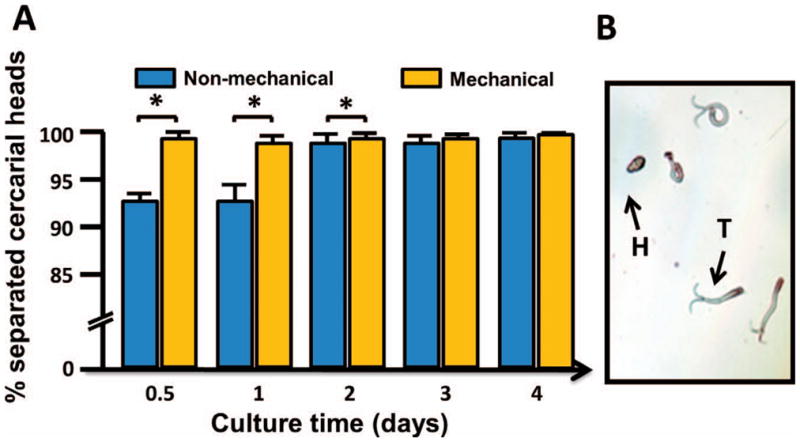

In the first experiment, we compared the rate of cercariae head and tail separation that occurred among mechanically and nonmechanically transformed cercariae. Significantly more cercariae heads separated from the tails at 0.5, 1, and 2 days with the use of the mechanical transformation method, though the vast majority of parasites that were transformed by the nonmechanical method had also undergone separation at the same time points (92–97%; Fig. 1). Thus, despite the statistical difference, the large number of cercariae undergoing transformation via the nonmechanical method is probably sufficient for most biological studies. In addition, by days 3 and 4, 97–99% of nonmechanically transformed cercariae had undergone separation and no statistical difference in the number of transformed cercariae was observed at these time points between the 2 transformation methods.

Figure 1.

Comparison of cercariae heads separated from tails using mechanical and nonmechanical transformation. (A) Mean percent transformed cercariae (separated heads from tails) by the 2 methods. (B) The image shows cercariae detached heads (H) and tails (T). Note: As all 3 figures are colored, please see the E-version of the article on line.

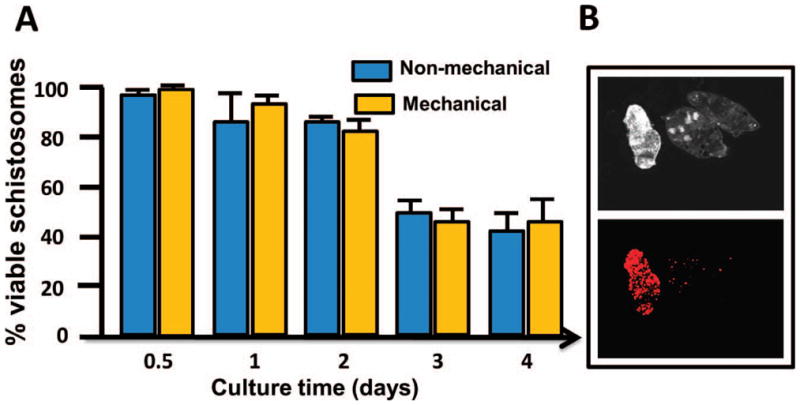

The separation study was followed by an experiment to further compare the effectiveness of both transformation methods at producing viable, or live, schistosomula. This was accomplished by staining the dead cells of the parasites with a PI reagent, which allowed us to distinguish dead parasites (transformed cercariae heads or schistosomula) from viable ones. The assay showed there was no significant difference in the percent of viably transformed cercariae by either transformation method at any of the time points (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Viability of transformed cercariae heads (schistosomula) by mechanical and nonmechanical transformation. (A) Mean percent viable schistosomula transformed by the 2 methods. (B) The images show the propidium iodide method used to distinguish the dead parasites from live ones. The top image shows 3 transformed cercariae heads in a field with the use of plane-polarized light. The bottom image shows superimposition of 1 dead transformed cercaria head stained red with the use of a 536-nm rhodamine filter.

Thus, with more than 97% of cercariae separated and undergoing transformation by day 2 by either method, and no difference in the quantity of viable schistosomula between the transformation methods, it is suggested there is no difference between the 2 methods in transforming cercariae into schistosomules. However, the mechanical method presents several problems to the process of transformation, i.e., an increased risk of sample contamination and an increased risk of infection to researchers working with the cercariae. Nonetheless, this study suggests the nonmechanical method, as described here, is an ideal alternative to obtaining high numbers of viable schistosomula.

Although various comparisons have been performed in previous studies as described above, many are no longer used, particularly among the nonmechanical methods. In the present effort, we compared the currently used double-ended–needle mechanical method to the culture medium based nonmechanical method, in which the culture medium used for the mechanical method described here is also currently used for culturing adult schistosome worms (Sayed et al., 2008). So, our study is quite different from earlier investigations and provides an additional option based on the currently used transformation method. Some earlier research that compared different mechanical methods showed differences in glucose concentration, osmolality, amino acid and lipid content, RNA and protein synthesis, and ultrastructure of tegument (Salafsky et al., 1988). It is unclear whether such changes also occur when comparing the mechanical and nonmechanical methods. In the present research, the culture medium used for the nonmechanical method was also used for the mechanical method. The only difference between the 2 approaches is the potential damage caused by the mechanical method. Because no evidence has shown that damage is an indispensable factor for in vitro transformation, it is unlikely that any changes caused by the damage will benefit the culture of schistosomula in vitro. In contrast, this nonmechanical method may offer several advantages over the mechanical method described above.

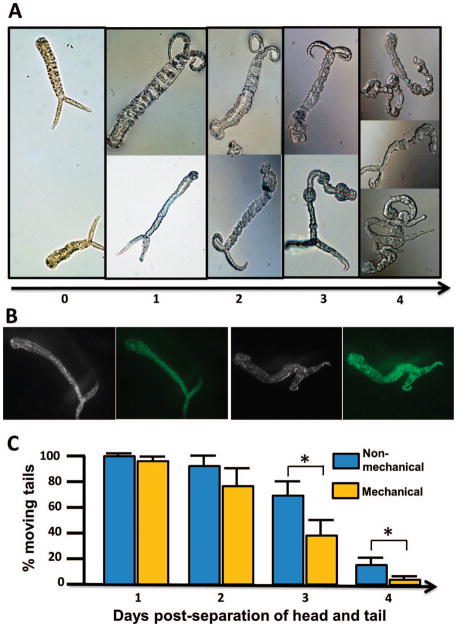

Finally, we observed the fate of the detached tails in culture, more specifically tail morphology and mobility. During definitive host infection, cercariae heads penetrate the skin of a host. In most cases, the tails detach and are no longer considered to be biologically functional and thus are generally ignored. Unexpectedly, we found the tails undergo morphological changes postseparation and can survive up to 4 days in culture.

Remarkably, the cercariae tails grew unknown structures throughout the course of the 4-day culture. Generally, by the first day of culture, the tails thicken and a bulbous structure appears at the head/tail junction. By the second day, the bulbous structure grew substantially larger. This unknown structure resembled a cercariae head in shape, but appeared smaller in size. By the third day, the bulbous structure was larger, and some of the detached cercariae tails began to grow several more smaller bulbous structures throughout their tail region. Finally, by day 4, the morphologically altered cercariae tails had coiled and contracted, and most had died (Fig. 3A). In addition, there were no observable morphological tail differences between the 2 methods.

Figure 3.

Mobility and morphological changes of the detached cercariae tails. (A) Examples of morphological changes of detached tails in culture from day 1 to day 4. (B) The images show the FDA method used to stain live cells on the detached tails. Two tails are shown. The black and white images each show 1 of the 2 different tails, and the fluorescent images show the superimposition of the 2 tails with the newly generated regions also stained green (alive) with the use of a 49- nm FITC filter. (C) Mean percent of cercariae tails in motion after each transformation method.

To determine whether these new cells or tissues were alive, we used FDA, which stains living cells. The stained cells in these regions of the detached tails were alive, implying the cells may have undergone proliferation (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the detached cercariae tails transformed by both methods exhibited chaotic and sporadic motion. They were extremely active at day 2 postseparation, with approximately 83–99% of the tails exhibiting motion. However, by days 3 and 4, tail mobility was significantly reduced, particularly among mechanically transformed cercariae, which only exhibited motion in 41% of cercariae at day 3 and 2% at day 4, compared to the 72% at day 3 and 17% at day 4 observed in cercariae tails that were transformed nonmechanically (Fig. 3C).

It seems the tails are able to regenerate additional cells or tissues, although further studies are required to understand the details of the newly generated tail structures better. It is hard to imagine that these new structures have any biological role because such changes do not occur in natural conditions. However, this intriguing change may reflect unique biological features of the cells in the tails. Further studies need to address the mechanism(s) of regeneration of the tissue in the detached tails. Regardless, these notable observations could have important implications for schistosome research, as the regenerated cells are likely to be highly proliferative and may also possess stem cell properties. Thus, this cercariae tail tissue should no longer be ignored, especially because it may be a potential candidate of study for the development of a schistosome cell line, a feature that has yet to be proven successful (Quack et al., 2010).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jarrett Hines-Kay for his assistance with statistical analysis and manuscript preparation and Dr. Eric S. Loker and Dr. Coen M. Adema for their valuable comments. This work was in part supported by NCRR ARRA (AI067686S) and NIH/NIAID RO1 (AI067686).

LITERATURE CITED

- Abdulla MH, Ruelas DS, Wolff B, Snedecor J, Lim KC, Xu F, Renslo AR, Williams J, Mckerrow JH, Caffrey CR, et al. Drug discovery for schistosomiasis: Hit and lead compounds identified in a library of known drugs by medium-throughput phenotypic screening. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2009;3:e478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj R, Krautz-Peterson G, Da’dara A, Tzipori S, Skelly PJ. Tegumental phosphodiesterase SmNPP-5 is a virulence factor for schistosomes. Infection and Immunity. 2011;79:4276–4284. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05431-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley DG, Wikel SK. Schistosoma mansoni: Simplified method for the production of schistosomules. Experimental Parasitology. 1974;35:44–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(74)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damian RT. Immunological aspects of host–schistosome relationships. Memo′ rias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 1987;82:13–16. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761987000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert GN, Chai M, Mcmanus DP. Biology of the schistosome lung-stage schistosomulum. Parasitology. 2007;134:453–460. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet. 2006;368:1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda NA, Abou el Naga IF, Mel Temsahi M, Sharaf IA. Schistosoma mansoni: A comparative study on two cercarial transformation methods. Journal of Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 1994;24:479–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CH. Parasites and poverty: The case of schistosomiasis. Acta Tropica. 2010;113:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loker ES, Hertel LA. Alterations in Biomphalaria glabrata plasma induced by infection with the digenetic trematode Echinostoma paraensei. Journal of Parasitology. 1987;73:503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann VH, Morales ME, Rinaldi G, Brindley PJ. Culture for genetic manipulation of developmental stages of Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitology. 2010;137:451–462. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manneck T, Braissant O, Haggenmuller Y, Keiser J. Isothermal microcalorimetry to study drugs against Schistosoma mansoni. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2011;49:1217–1225. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02382-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JN, Jolly ER. Cercarial transformation and in vitro cultivation of Schistosoma mansoni schistosomules. [Accessed 28 February 2012.];Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2011 54:e3191. doi: 10.3791/3191. Available at: http://www.jove.com/details.php?id=3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker-Manuel SJ, Ivens AC, Dillon GP, Wilson RA. Gene expression patterns in larval Schistosoma mansoni associated with infection of the mammalian host. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011;5:e1274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peak E, I, Chalmers W, Hoffmann KF. Development and validation of a quantitative, high-throughput, fluorescent-based bioassay to detect schistosoma viability. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4:e759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quack T, Wippersteg V, Grevelding CG. Cell cultures for schistosomes—Chances of success or wishful thinking? International Journal for Parasitology. 2010;40:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Pinto FJ, Gazzinelli G, Howells RE, Mota-Santos TA, Figueiredo EA, Pellegrino J. Schistosoma mansoni: Defined system for stepwise transformation of cercaria to schistosomule in vitro. Experimental Parasitology. 1974;36:360–372. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(74)90076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salafsky B, Fusco AC, Whitley K, Nowicki D, Ellengerger B. Schistosoma mansoni: Analysis of cercarial transformation methods. Experimental Parasitology. 1988;67:116–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed AA, Simeonov A, Thomas CJ, Inglese J, Austin CP, Williams DL. Identification of oxadiazoles as new drug leads for the control of schistosomiasis. Nature Medicine. 2008;14:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nm1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani′c S, Dvorak J, Horn M, Braschi S, Sojka D, Ruelas DS, Suzuki B, Lim KC, Hopkins SD, Mckerrow JH, et al. RNA interference in Schistosoma mansoni schistosomula: Selectivity, sensitivity and operation for larger-scale screening. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4:e850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]