Abstract

Study goals were to examine the conditions under which congruent and incongruent patterns of parents’ division of household labor and gender role attitudes emerged, and the implications of these patterns for youth gender development. Questionnaire and phone diary data were collected from mothers, fathers, and youths from 236 Mexican American families in the southwestern US. Preliminary cluster analysis identified three patterns: Traditional divisions of labor and traditional attitudes, egalitarian divisions of labor and egalitarian attitudes, and an incongruent pattern, with a traditional division of labor but egalitarian attitudes. MANOVAs, and follow-up, mixed- and between-group ANOVAs, revealed that these groups of families differed in parents’ time constraints, socioeconomic resources, and cultural orientations. Mothers in the congruent egalitarian group worked more hours and earned higher incomes as compared to mothers in the congruent traditional and incongruent groups, and the emergence of the incongruent group was grounded in within-family, inter-parental differences in work hours and incomes. Parents’ patterns of gendered practices and beliefs were linked to their youths’ housework participation, time with mothers versus fathers, and gender role attitudes. Youths in the congruent traditional group had more traditional gender role attitudes than those in the congruent egalitarian and incongruent groups, and gender atypical housework participation and time with parents were only observed in the congruent egalitarian group. Findings demonstrate the utility of a within-family design to understand complex gendered phenomena, and highlight the multidimensional nature of gender and the importance of contextualizing the study of ethnic minorities.

Keywords: gender role attitudes, gender socialization, household labor, Mexican American families, pattern analytic approach

Introduction

Estimates based on national representative samples from 30 countries (including the US) indicate that married women are responsible for about two thirds of all household tasks in the family (Greenstein, 2009). Researchers have long tried to understand why housework is divided in gender-biased ways and, to a lesser extent, how such arrangements may affect youth gender development (see Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010 and McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003 for reviews of studies conducted mainly with European American samples in the US on the division of housework and youth gender development, respectively). Most of this work, however, is based on European American families in the US. Although Mexican Americans constitute the largest and fastest-growing ethnic minority group in the US (US Census Bureau, 2010), their everyday family experiences, including how they assign household tasks, remain under-explored (Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010). Spouses’ routine involvement in housework could be conceptualized as behavioral enactment of their attitudes about marital roles (Thompson & Walker, 1989). However, a growing body of research shows that gender is complex and multidimensional, and that different facets of gender are not necessarily tightly related to one another (see Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006 for a review of related studies conducted mainly with European American samples in the US).

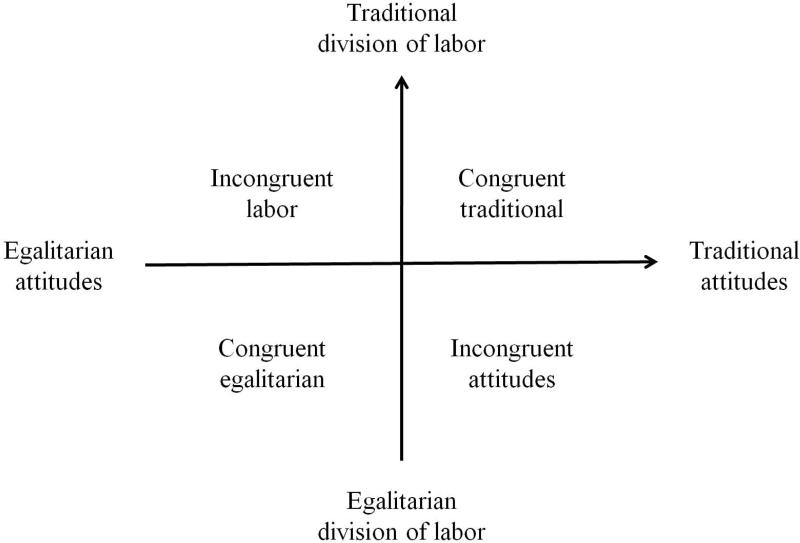

Indeed, in a study based on national representative samples from five European countries, Cromption and Lyonette (2006) were able to classify married couples into distinct groups defined by spouses’ housework allocation and gender ideologies (see Figure 1), including congruent traditional, congruent egalitarian, and incongruent labor (i.e., traditional divisions of household labor but egalitarian gender role attitudes). Possibly because many household tasks are perceived by Anglo individuals to be tedious and boring (Coltrane, 2000) and favorable attitudes, on a conceptual level, are particularly important in motivating voluntary involvement in undesirable tasks (Ajzen, 2001), an insufficient number of families in Cromption and Lyonette's study fell under the incongruent attitudes category (i.e., egalitarian divisions of household labor but traditional gender role attitudes) to form a distinct group. Building on this classification framework, we drew on questionnaire and phone diary data collected from mothers, fathers, and youths from Mexican American families in the southwestern US and used cluster analysis as a preliminary step to classify these families into congruent traditional, congruent egalitarian, and incongruent labor groups. Our study goals were to identify the conditions under which these congruent and incongruent patterns of parents’ gendered practices and beliefs emerged and to assess the implications of these patterns for youth gender development, using MANOVAs and a series of follow-up, mixed- and between-group ANOVAs. In developing our arguments, we only relied on empirical studies that were US-based to make sure that they were contextually relevant in understanding our sample. We also noted the ethnic background of the samples when the studies were conducted with a particular ethnic group, as cultural orientations, as we describe below, play an important role in shaping spouses’ division of household labor.

Figure 1.

Classification framework of parents’ divisions of household labor and gender role attitudes.

Parents’ Time Constraints, Socioeconomic Resources, and Cultural Orientations

Our first goal was to identify the conditions under which parents’ patterns of gendered behaviors and attitudes emerged. An ecological perspective suggests that family roles, socioeconomic factors, and enculturation and acculturation processes are closely linked to family dynamics among ethnic minorities (García Coll et al., 1996). In a parallel fashion, the literature on the division of household labor points to the importance of time constraints, socioeconomic resources, and cultural orientations in understanding mothers’ and fathers’ gendered practices and beliefs (Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010).

First, time constraints theory posits that couples make rational decisions to assign more household tasks to the spouse with more free time (Coverman, 1985). Previous studies based on European American (e.g., Blair & Lichter, 1991; Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992) and Mexican American (Golding, 1990; Pinto & Coltrane, 2009) families in the US have shown that husbands with wives who work more hours outside homes contribute more to household responsibilities. Little is known about how work hours are related to gender role attitudes, but employed immigrant women, as compared to their non-employed counterparts, are more exposed to the dominant US culture and better able to build social networks in the workplace (Vega, 1990), both of which may empower women and lead to the liberalization of their gender ideologies (Kroska & Elman, 2009). Therefore, we expected that mothers in congruent traditional families would work fewer hours as compared to mothers in congruent egalitarian families. However, the behavioral expression of attitudes is often limited by environmental constraints (Ajzen, 2001). Even when both parents prefer an egalitarian division of household labor, when the mother has more free time than does the father, it may be rational for her to take on more household tasks. Therefore, we also expected that mothers in incongruent labor families would work fewer hours as compared to mothers in congruent egalitarian families, and that inter-parental differences in work hours (with fathers working more) would be greater in incongruent labor than in congruent egalitarian families.

Second, social exchange theory assumes that household tasks are undesirable and that the spouse with more socioeconomic resources has more power to buy her- or himself out of these chores (Huston & Burgess, 1979). Several studies based on European American (e.g., Blair & Lichter, 1991; Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992) and Mexican American (Coltrane & Valdez, 1993; Pinto & Coltrane, 2009) families in the US found that couples had a more balanced division of housework when the wives were more educated and had higher incomes. Modern educational systems expose students to democratic ideals and female role models, and not surprisingly, more educated individuals have more egalitarian attitudes about marital roles (see Chatard & Selimbegovic, 2007 for a review of related studies conducted with samples from both individualistic and collectivistic countries). Higher education also leads to better paying jobs. A longitudinal study based on a national representative sample from the US indicated that wives who contributed more to the household income had more egalitarian gender role attitudes (Raley, Matting, & Bianchi, 2006). Therefore, we expected that mothers in congruent traditional families would be less educated and earn lower income as compared to mothers in congruent egalitarian families. However, household tasks, especially core ones that have to be done on a daily or regular basis, are commonly seen to be tedious and boring (Coltrane, 2000). Even when both parents consider doing housework as a gender-neutral responsibility, if the father brings more resources to the family than does the mother, he may have more power to avoid these undesirable tasks. Therefore, we expected that mothers in incongruent labor families would be less educated and earn lower incomes as compared to mothers in congruent egalitarian families, and that inter-parental differences in incomes (with fathers earning more) would be greater in incongruent labor than in congruent egalitarian families.

Finally, cultural orientations theory suggests that cultures provide social frames of reference that direct behaviors and attitudes (Triandis, 1989), and that in many cultures, traditions and values provide justification for the “natural” roles of women and men in the family (West & Zimmerman, 1987). Indeed, traditional Latino marriages are often shaped by the gendered cultural ideals of “marianismo” and “machismo” (McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2000): The former highlights women's role as mothers and encourages them to be loyal and self-sacrificing, whereas the latter stresses men's role as head of the household and celebrates their dominance and sexual virility. Ayala's (2006) and Denner and Dunbar's (2004) qualitative research, for example, illustrates how Mexican American mothers in the US conform to the humble, selfless ideal and teach their daughters to cook and clean. The dominant US culture, in contrast, holds that individuals should be treated equally. Mexican American parents who have been extensively exposed to the dominant US culture may subscribe to Anglo practices and beliefs, and display a more egalitarian division of household labor and gender role attitudes (Parrado & Flippen, 2005; Pinto & Coltrane, 2009). Therefore, we expected that parents in congruent traditional families would have higher Mexican and lower Anglo cultural orientations as compared to parents in congruent egalitarian families.

Youths’ Gendered Behaviors and Attitudes

Our second goal was to examine the implications of parents’ patterns of the division of household labor and gender role attitudes for their youths’ gendered behaviors and attitudes. Gender socialization in Mexican American families in the US has typically been studied within a framework of risks and pathology (Suárez-Orozco & Qin, 2006). As emphasized by an ecological perspective (García Coll et al., 1996), however, normative, day-to-day experiences with parents are also important for shaping youth gender development in ethnic minority families.

Parents are theorized to play roles as models, opportunity providers, and instructors in youth gender development (Parke & Buriel, 2006). As models, parents indirectly convey gendered messages by engaging in gender-typed activities. To the extent that mothers’ and fathers’ involvement in housework is differentiated, the distinct roles of women and men may be particularly salient and easy to learn (Bussey & Bandura, 1999), and girls will be more involved in housework than will boys. As opportunity providers, parents orchestrate the daily activities of their children. Traditional parents have been shown to participate in more joint activities with children of their own gender (see McHale at al., 2003 and Suárez-Orozco & Qin, 2006 for reviews of related studies conducted with European American and ethnic minority samples in the US, respectively). To the extent that these parents also enforce a traditional division of labor, girls will have more opportunities to do housework with their mothers (but not fathers) than will boys. Finally, as instructors, parents explicitly communicate their beliefs about gender roles by providing instruction and guidance to their youths, and such processes should lead youths with traditional parents to develop more traditional attitudes themselves (McHale at al., 2003).

Existing research based on European American (e.g., Cunningham, 2001; Marks, Lam, & McHale, 2009) and Mexican American (Denner & Dunbar, 2004; Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004) families in the US suggests that parents’ division of household labor and gender role attitudes may influence youths’ gendered behaviors and attitudes. In fact, the process of immigration and resettlement may intensify these socialization forces. For example, due to the necessity for both parents to work outside the home and parents’ lack of English proficiency, youths may have to increase their involvement in housework and act as language brokers. Some work shows that, in ethnic minority families in the US, girls are typically chosen over boys to take care of younger siblings and to translate school, medical, and legal documents (Suárez-Orozco & Qin, 2006). Moreover, in Mexican American families in the US, girls, more so than boys, are expected to preserve the ethnic culture and help maintain extended family networks (Ayala, 2006). Therefore, we expected that girls and boys in congruent traditional families would show greater differences in housework participation and time with mothers versus fathers and would hold more traditional gender role attitudes as compared to youths in congruent egalitarian families. It is important to note that modeling of gendered behaviors and tutoring of gender knowledge are facilitated by each other, with greatest adherence observed in the learner when what is modeled is congruent with what is taught by the instructor (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Therefore, we expected that girls and boys in incongruent labor families would differ more in their gendered behaviors and would display more traditional attitudes as compared to youths in congruent egalitarian families.

Study Goals and Hypotheses

In sum, this study was designed to examine the sociocultural characteristics and developmental implications of congruent and incongruent patterns of parents’ housework allocation and gender ideologies in Mexican American families. Based on prior literature, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Mothers in congruent traditional and incongruent labor families would work fewer hours as compared to mothers in congruent egalitarian families (1.1), and inter-parental differences in work hours would be greater in incongruent labor than in congruent egalitarian families (1.2).

Hypothesis 2: Mothers in congruent traditional and incongruent labor families would be less educated (2.1a) and earn lower incomes (2.1b) as compared to mothers in congruent egalitarian families, and inter-parental differences in education (2.2a) and income (2.2b) levels would be greater in incongruent labor than in congruent egalitarian families.

Hypothesis 3: Parents in congruent traditional families would have higher Mexican (3.1) and lower Anglo (3.2) orientations as compared to parents in congruent egalitarian families.

Hypothesis 4: Girls and boys in congruent traditional and incongruent labor families would show greater differences in housework participation (4.1) and in time with mothers versus fathers (4.2) and would have more traditional gender role attitudes (4.3) as compared to girls and boys in congruent egalitarian families.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a study of family socialization and adolescent development in Mexican American families. Families’ contact information was obtained from schools in and around a southwestern metropolitan area of the US. Recruitment letters in both Spanish and English were sent to 1,856 Mexican American families, and follow-up telephone calls were made by bilingual staff to determine the interest in participation. Given the goal of the larger study, to examine normative experiences of two-parent Mexican American families, families were eligible for participation if (a) mothers were of Mexican origin; (b) at least one adolescent sibling lived at home; (c) biological mothers and biological or long-term (> 10 years) adoptive fathers lived at home; and (d) fathers worked at least 20 hours per week (and thus families had a relatively stable source of income). Of those eligible families (N = 421), 284 families (67%) agreed to participate, 95 families (23%) refused, and we were unable to reconnect with the remaining 42 families (10%). Due to budget constraints, enrollment of families ended when we completed home interviews with 246 families, surpassing the target sample size of 240 families. This study was based on data from 236 families; we excluded 10 families that did not provide data on parents’ division of household labor or gender role attitudes.

The sample included mostly dual-earner (67% of mothers were employed) families of a range of education and income levels, from poverty to upper class. The average ages of mothers and fathers were 39.00 (SD = 4.63) and 41.70 (SD = 5.78) years, respectively. Most parents (71% of mothers and 69% of fathers) had been born outside the US. Seventy percent of parents were interviewed in Spanish, and the rest were interviewed in English. The average age of youths was 15.72 (SD = 1.55) years, and about half were female. Forty-six percent of youths had been born outside the US, and 17% were interviewed in Spanish. The means and standard deviations of parents’ work hours, education and income levels, and cultural orientations, which provide additional information about the background characteristics of the sample, can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Parents’ Time Constraints, Socioeconomic Resources, and Cultural Orientations

| Congruent traditional | Congruent egalitarian | Incongruent labor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers’ work hours | 24.41 (22.95)a | 37.50 (17.03)b | 25.21 (22.40)a |

| Fathers’ work hours | 49.92 (15.45)a | 52.63 (15.80)ab | 56.63 (16.57)b |

| Parental differences in work hours1 | 25.51 (26.41)ab | 15.13 (25.62)a | 31.15 (27.72)b |

| Mothers’ education (years) | 8.83 (3.93)a | 11.55 (3.24)b | 11.32 (3.18)b |

| Fathers’ education (years) | 8.07 (4.31)a | 11.42 (3.38)b | 11.03 (4.26)b |

| Parental differences in education1 | -.77 (3.74)a | -.13 (2.74)a | -.29 (3.57)a |

| Mothers’ incomes ($) | 7,743 (11,694)a | 21,537 (17,393)b | 11,907 (16,228)a |

| Fathers’ incomes ($) | 31,423 (23,252)a | 41,308 (29,143)ab | 42,733 (24,670)b |

| Parental differences in incomes1 | 23,680 (25,779)ab | 19,771 (28,587)a | 30,826 (26,325)b |

| Mothers’ Mexican orientations | 4.20 (.57)a | 3.64 (.85)b | 4.05 (.66)a |

| Fathers’ Mexican orientations | 4.15 (.63)a | 3.54 (.94)b | 3.84 (.79)b |

| Mothers’ Anglo orientations | 2.62 (.89)a | 3.28 (1.05)b | 3.02 (.86)b |

| Fathers’ Anglo orientations | 2.69 (.84)a | 3.41 (.86)b | 3.06 (.90)b |

Note. A one-way MANOVA indicated that the groups were significantly different in terms of the combined function of the variables included in the Table, p < .01.

Scores on parents’ Mexican and Anglo orientations represent item averages (range = 1-5).

Computed as fathers’ minus mothers’ scores, such that negatively signed scores signify mothers scoring higher as compared to fathers and positively signed scores signify fathers scoring higher as compared to mothers.

Scores with different subscripts within row are significantly different, p < .05.

Scores with different subscripts within row are significantly different, p < .05.

Procedure

We collected data through home and phone interviews. Trained bilingual interviewers visited families to conduct home interviews. At the beginning of the interview, informed consent was obtained. Family members were individually interviewed about their family relationships and individual characteristics. Home interviews averaged between two to three hours in duration. In the three to four weeks following the home interviews, parents completed four (three weekdays, one weekend day) and youths completed seven (five weekdays, two weekend days) nightly phone interviews. Trained bilingual interviewers called family members individually, and guided them through a list of 86 activities (e.g., laundry, gardening, listening to music) and probed for the duration and social contexts (i.e., with whom they engaged in the activities) of any activities completed during the day. Phone interviews were 10 to 15 minutes in duration. Families were given $100 for home interview and $100 for phone interview participation.

Measures

Two independent translators forward and back translated all measures into Spanish for the local Mexican dialect. All final translations were reviewed and, discrepancies, resolved. For home interview measures, scores were averaged, and higher scores reflect higher levels of each construct. For phone interview measures, reports of activities were aggregated, and higher scores reflect more time (in minutes) spent on each category of activity.

Parents provided information about family members’ gender, nativity, and age, and their work hours and education and income levels in the home interview. Other questionnaire measures described below were also collected in the home interview.

Parents’ gender role attitudes were assessed using six items developed by Knight et al. (2010). Mothers and fathers rated such items as, “Las madres son la persona principal responsable por la crianza de los hijos/Mothers are the main person responsible for raising children,” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Cronbach alphas were .72 for mothers and .68 for fathers.

Parents’ Mexican and Anglo orientations were assessed using two subscales of the 30-item Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II (ARSMA II; Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). Mothers and fathers rated such items as, “Disfruto la televisión en Español/I enjoy watching TV in Spanish,” and, “I speak English/ Yo hablo Inglés,” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (1) to extremely often or almost always (5). Cronbach alphas were .87 for mothers’ and .91 for fathers’ Mexican orientations and .90 for mothers’ and .91 for fathers’ Anglo orientations.

Youths’ gender role attitudes were assessed using a 10-item scale developed by Hoffman and Kloska (1995). Youths rated such items as, “El trabajo del esposo es más importante que el de la esposa/A husband's job is more important than a wife's,” on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4). Cronbach alpha was .87.

Parents’ and youths’ daily time use was assessed in the phone interview. To assess parents’ housework participation, during each of their four calls, mothers and fathers reported independently how much time they spent on five core household tasks (i.e., doing dishes, cooking meals, shopping for food, doing laundry, and cleaning the house), tasks that have to be done on a daily or regular basis (Coltrane, 2000). The division of household labor was calculated as the percentage of total housework (done by either parent) that was done by the mother. This proportion score ranged from .25 to 1.00 in our sample.

To assess youths’ housework participation, during each of their seven calls, youths reported how much time they spent on six core household tasks (i.e., doing dishes, cooking meals, shopping for food, doing laundry, cleaning the house, and cleaning their own room).

To assess youths’ time with mothers and with fathers, during each of their seven calls, youths reported how much time their mothers and fathers spent with them on each of the activities youths completed during the day. The high correlations between parents’ and youths’ reports of their shared time from their four common calls, r(229) = .86 for mothers and r(229) =.83 for fathers, provided strong evidence of inter-reporter reliabilities for our time use measures.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

To create groups that showed substantial variation in parents’ division of household labor and gender role attitudes and that were large enough for further comparisons, we conducted a cluster analysis, as outlined by Whiteman and Loken (2006). On the basis of interpretability, group sizes, and several other stopping criteria (e.g., dendrogram patterns, replicability using alternative clustering methods), we chose a three-cluster solution as the best representation of the data. Consistent with the classification framework of Cromption and Lyonette (2006), three distinct groups of families were identified: A congruent traditional group (N = 92), in which the mother did most (i.e., about 90%) of the housework and both parents had traditional gender role attitudes (i.e., averaging almost 4 on a 5-point scale of traditionality), a congruent egalitarian group (N = 52), in which the mother and father more closely split the housework and shared egalitarian gender role attitudes (i.e., averaging below the midpoint of the measure), and an incongruent labor group (N = 92), in which the mother did most of the housework, but both parents had more egalitarian gender role attitudes. An incongruent attitudes group with an egalitarian division of labor but traditional attitudes, however, was never identified.

Confirming that these groups were different in terms of parents’ division of household labor and gender role attitudes, a one-way MANOVA revealed a significant effect of group for the combined function of these variables, F(6, 462) = 140.24, p < .01, ε = .65. Further confirming that the three groups reflected congruence and incongruence between parents’ gendered practices and beliefs, a follow-up, one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of group for parents’ division of household labor, F(2, 233) = 193.64, p < .01, ε = .62. Tukey tests indicated that mothers in the congruent egalitarian group were responsible for significantly smaller portions of household tasks than those in both the congruent traditional and incongruent labor groups. A follow-up, 3 (Group) × 2 (Parent) mixed-model ANOVA (with parent as the within-group factor) also revealed a significant effect of group for parents’ gender role attitudes, F(2, 233) = 216.76, p < .01, ε = .65. Tukey tests indicated that both mothers’ and fathers’ gender role attitudes were more traditional in the congruent traditional group than in the congruent egalitarian and incongruent labor groups. Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations of parents’ division of household labor and gender role attitudes of the sample.

Table 2.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Parents’ Division of Household Labor and Gender Role Attitudes

| Congruent traditional | Congruent egalitarian | Incongruent labor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The division of household labor | .89 (.09)a | .58 (.16)b | .92 (.07)a |

| Mothers’ gender role attitudes | 3.87 (.58)a | 2.53 (.63)b | 2.41 (.64)b |

| Fathers’ gender role attitudes | 3.72 (.65)a | 2.73 (.69)b | 2.87 (.79)b |

Note. A one-way MANOVA indicated that the groups were significantly different in terms of the combined function of the variables included in the Table, p < .01.

Scores on the division of household labor represents the percentage of total housework (done by either parent) that was done by the mother.

Scores on parents’ gender role attitudes represent item averages (range 1-5).

Scores with different subscripts within row are significantly different, p < .05.

Scores with different subscripts within row are significantly different, p < .05.

Tests of Study Hypotheses

Our study goals were to examine the sociocultural characteristics and developmental implications of congruent and incongruent patterns of parents’ housework allocation and gender ideologies in Mexican American families. To examine whether, overall, the three groups of families differed in terms of parents’ time constraints, socioeconomic resources, and cultural orientations as well as youths’ gendered behaviors and attitudes, we conducted two one-way MANOVAs. A significant group effect for the combined function of parents’ work hours, education and income levels, and Mexican and Anglo orientations, F(20, 448) = 3.94, p < .01, ε = .15, and for the combined function of youths’ housework participation, time with parents, and gender role attitudes, F(8, 448) = 3.84, p < .01, ε = .06, allowed us to use a series of mixed- and between-group ANOVAs to follow up on the group differences and test each of our four hypotheses separately.

Parents’ time constraints, socioeconomic resources, and cultural orientations

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of parents’ work hours, education and income levels, and Mexican and Anglo orientations, and the means and standard deviations of father-mother differences when Group × Parent interactions were tested.

Beginning with parents’ work hours, a 3 (Group) × 2 (Parent) mixed-model ANOVA revealed a significant effect of group, F(2, 233) = 5.81, p < .01, ε = .03, and a significant Group × Parent interaction, F(2, 233) = 5.95, p < .01, ε = .04. Tukey tests indicated that, in support of Hypothesis 1.1, mothers’ work hours were significantly higher in the congruent egalitarian group than in the congruent traditional and incongruent labor groups. Paired t-tests and between-group comparisons further showed that, in support of Hypothesis 1.2, although fathers in all three groups worked significantly more hours than did mothers, this inter-parental difference was significantly greater in the incongruent labor than in the congruent egalitarian group.

Analysis of parents’ education revealed a significant effect of group, F(2, 233) = 19.76, p < .01, ε = .14. Tukey tests indicated that, in partial support of Hypothesis 2.1a, mothers’ education levels were significantly lower in the congruent traditional than in the congruent egalitarian group. Mothers in the congruent egalitarian and incongruent labor groups, however, did not differ. Moreover, the Group × Parent interaction was not significant, leaving Hypothesis 2.2a, which predicted greater inter-parental differences in education levels in the incongruent labor than in the congruent egalitarian group, unsupported. Analysis of parents’ incomes revealed a significant effect of group, F(2, 233) = 10.60, p < .01, ε = .07, and a significant Group × Parent interaction, F(2, 233) = 3.26, p < .05, ε = .02. Tukey tests indicated that, in support of Hypothesis 2.1b, mothers’ incomes were significantly higher in the congruent egalitarian than in the congruent traditional and incongruent labor groups. Paired t-tests and between-group comparisons showed that, in support of Hypothesis 2.2b, although fathers in all three groups earned significantly more than did mothers, this inter-parental difference was significantly greater in the incongruent labor than in the congruent egalitarian group.

Analysis of parents’ Mexican orientations revealed a significant effect of group, F(2, 233) = 13.56, p < .01, ε = .10. Tukey tests showed that both mothers’ and fathers’ Mexican orientations were significantly higher in the congruent traditional group than in the congruent egalitarian group, lending support to Hypothesis 3.1. Analysis of parents’ Anglo orientations revealed a significant effect of group, F(2, 233) = 12.55, p < .01, ε = .09. Tukey tests showed that both mothers’ and fathers’ Anglo orientations were significantly higher in the congruent egalitarian than in the congruent traditional group, lending support to Hypothesis 3.2.

Youths’ gendered behaviors and attitudes

Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations of youths’ gender role attitudes, and the separate means and standard deviations of youths’ housework participation and time with mothers versus fathers and for girls and boys (when Group × Gender interactions were tested).

Table 3.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Youths’ Gendered Behaviors and Attitudes

| Congruent traditional | Congruent egalitarian | Incongruent labor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (minutes) on housework | |||

| Girls | 397.17 (245.16)x | 280.52 (142.13)x | 306.27 (131.35)x |

| Boys | 173.81 (111.64)y | 230.13 (135.70)x | 165.98 (94.14)y |

| Time (minutes) with mothers versus fathers1 | |||

| Girls | 416.42 (345.55)x | 143.29 (300.88)x | 366.88 (388.85)x |

| Boys | -101.49 (313.90)y | 29.37 (312.73)x | 11.98 (339.80)y |

| Gender role attitudes | 2.30 (.53)a | 1.90 (.54)b | 1.99 (.54)b |

Note. A one-way MANOVA indicated that the groups were significantly different in terms of the combined function of the variables included in the Table, p < .01.

Scores on youths’ gender role attitudes represent item averages (range = 1-4).

Computed as time with mothers minus time with fathers, such that negatively signed scores signify youths spending more time with fathers than with mothers and positively signed scores signify youths spending more time with mothers than with fathers.

Scores were compared between girls and boys from different families, and different subscripts within column are significantly different, p < .05.

Scores were compared between girls and boys from different families, and different subscripts within column are significantly different, p < .05.

Scores with different subscripts within row are significantly different, p < .05.

Scores with different subscripts within row are significantly different, p < .05.

Beginning with youths’ housework participation, a 3 (Group) × 2 (Gender) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of gender, F(1, 231) = 41.60, p < .01, ε = .16, and a significant Group × Gender interaction, F(2, 231) = 5.05, p < .01, ε = .04. Girls (M = 338.94, SD = 193.10), on average, spent more time on housework than did boys (M = 185.75, SD = 114.83). Within-group, independent t-tests further indicated that, in support of Hypothesis 4.1, although girls in the congruent traditional and incongruent labor groups spent significantly more time on housework than did boys, this gender difference was not evident in the congruent egalitarian group. Turning to time with parents, a 3 (Group) × 2 (Gender) × 2 (Parent) mixed-model ANOVA (with parent as the within-group factor) revealed a significant Group × Gender × Parent interaction, F(2, 225) = 5.61, p < .01, ε = .04. Within-group, independent t-tests indicated that, in support of Hypothesis 4.2, although girls in the congruent traditional and incongruent labor groups spent significantly more time with mothers than with fathers as compared to boys, this gender difference was not evident in the congruent egalitarian group. Finally, a 3 (Group) × 2 (Gender) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of gender, F(1, 235) = 6.13, p < .01, ε = .03, and a significant effect of group, F(2, 235) = 12.15, p < .01, ε = .10, for gender role attitudes. Girls (M = 2.00, SD = .58), on average, had less traditional gender role attitudes than did boys (M = 2.19, SD = .53). Tukey tests indicated that, in partial support of Hypothesis 4.3, youths in the congruent traditional group had significantly more traditional gender role attitudes than did youths in the congruent egalitarian group. Youths in the incongruent labor and congruent egalitarian groups, however, did not differ.

Discussion

Despite extensive evidence showing that Mexican Americans in the US comprise a highly heterogeneous group (Landale & Oropesa, 2007), a considerable amount of research continues to use ethnic comparative designs to document greater gender traditionality in these families. Our study, in contrast, adopted an ethnic homogeneous design to examine within-group differences among Mexican American families across different facets of gender. Such an approach allows researchers to capture the diversity that exists within cultural groups, and avoids the pathologizing of ethnic minority families that can emerge from some ethnic comparative studies, when practices of the host culture are used as the standard for comparisons and any divergence from these norms is understood as deficient (García Coll et al., 1996). Our analyses revealed that Mexican American families could be traditional or egalitarian in their divisions of household labor and/or gender role attitudes, posing challenges to the stereotypical view of Latino families as universally traditional in their gender dynamics. Instead of solely focusing on between-group variation, future researchers should also consider within-group variation when studying ethnic minority families (Suárez-Orozco & Qin, 2006).

In addition to within-group variation, our analyses also revealed within-family variation in parents’ gendered practices and beliefs. Consistent with a multi-dimensional perspective of gender (Ruble et al., 2006) and Crompton and Lyonette's (2006) classification framework, in some Mexican American families, parents had egalitarian gender role attitudes but still engaged in a traditional division of household labor. Just as individuals can be gender-typical and atypical in different aspects, couples, and presumably families (Marks et al., 2009), can be traditional in one way and egalitarian in another. Most prior work on housework has been variable-oriented, that is, directed at identifying correlations between variables, such as housework allocation and gender ideologies, that hold for the “average” individual. A pattern analytic approach contrasts with a variable-oriented approach in assuming that individuals are unique, and that variables may be correlated in different ways for different individuals (von Eye & Bogat, 2006). Perhaps more importantly, a pattern analytic approach also assumes that it often requires only a small number of patterns to describe different, but lawful, configurations of variables in reality, and that it is the overall pattern, not the isolated variables, that defines the meaning of the involved factors. As we describe below, family roles and socioeconomic factors may operate to motivate congruent and incongruent inter-parental patterns of gender dynamics, and these, in turn, may have important implications for youth development.

Parents’ Time Constraints, Socioeconomic Resources, and Cultural Orientations

As predicted by Hypotheses 1.1 and 2.1b, mothers in the congruent egalitarian group were characterized by higher work involvement and higher socioeconomic power as compared to mothers in the congruent traditional and incongruent labor groups. Inter-parental comparisons further revealed that, as predicted by Hypotheses 1.2 and 2.2b, although fathers worked more hours and earned higher incomes than did mothers in all the three groups, inter-parental differences were smaller in the congruent egalitarian than in the incongruent labor group. The emergence of the incongruent labor group was linked to social and economic processes embedded within the household: Although parents in both egalitarian and incongruent groups had egalitarian gender role attitudes, when fathers had relatively less time available at home (Coverman, 1985) and brought relatively more financial resources to the family (Huston & Burgess, 1979), mothers took on a larger portion of household responsibilities. On a theoretical level, the idea that two spouses may have different interests in their marriage and that they each may use their own responsibilities and resources to achieve their individual goals is consistent with a systems perspective on families (Parke & Buriel, 2006). On a methodological level, the findings that the congruent egalitarian and incongruent labor groups varied not only in parents’ individual characteristics, but also in inter-parental differences in these characteristics, underscore the importance of drawing data from both wives and husbands to capture dynamic processes within the marital relationship.

Hypotheses 2.1a was only partially, and Hypothesis 2.2a was not, supported by our results: Although mothers in the congruent egalitarian group were better educated as compared to mothers in the congruent traditional group, mothers in the congruent egalitarian and incongruent labor groups did not differ. Moreover, inter-parental differences in education did not vary between the latter two groups as we expected. Taking also into account the significant findings on parents’ incomes (Hypotheses 2.1b and 2.2b), our findings may suggest that, at least in our sample, education levels tapped more into parents’ previous exposures to democratic ideals and female role models (and thus endorsement of egalitarian gender role attitudes; Chatard & Selimbegovic, 2007) than into socioeconomic power. In fact, many immigrants report experiencing a significant loss of capacity to translate the education levels achieved in their home country into earning ability in the US (García Coll et al., 1996), meaning that a better educational background may not be able to give them more leverage in negotiating for a more self-favoring division of household labor. More work is needed to understand the conditions under which educational attainment undergirds socioeconomic power in ethnic minority families. Finally, as predicted by Hypotheses 3.1 and 3.2, parents in the congruent traditional group were more enculturated and less acculturated as compared to parents in the congruent egalitarian group, confirming that cultural traditions and values may serve to support family gender dynamics (Triandis, 1989; West & Zimmerman, 1987).

There has been a strong tendency for researchers to make reference to traditional cultural concepts when explaining family processes among Mexican Americans in the US (Landale & Oropesa, 2007). However, as elaborated by McLoyd et al. (2000), an over-reliance on cultural interpretations of gendered practices and beliefs may obscure the influences of other social contextual factors. Individuals in society are differentially stratified along a hierarchical system based on multiple social position factors, including social class, ethnicity, and gender (García Coll et al., 1996). One's position in such a social hierarchy, in turn, affords and constrains access to various social and economic resources. Our results show that family roles and socioeconomic factors are as important as cultural processes in understanding variation in gender dynamics within Mexican American families. Instead of relying on cultural heritage as a monolithic explanation for marital and family interactions, future research on ethnic minority families should also take into account the immediate socioeconomic contexts and explore the relations between social position, socioeconomic resources, and gender dynamics.

Youths’ Gendered Behaviors and Attitudes

In partial support of Hypothesis 4.3, although youths in the congruent egalitarian group had more egalitarian gender role attitudes as compared to youths in the egalitarian traditional group, youths in congruent egalitarian and incongruent labor groups did not differ. These findings may suggest that parents’ instruction and guidance alone are powerful enough to shape youths’ gender role attitudes (Parke & Buriel, 2006). Even though parents in the incongruent labor group did not “walk the talk,” youths appeared to agree with their parents’ views about female and male roles. Recent studies on persuasion have found that it is easier to initiate an attitudinal change, which often only involves heuristic cognitive restructuring, than a behavioral change, which always requires breaking old habits and/or establishing new ones (see Bohner & Dickel, 2010 and Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2008 for reviews of studies conducted mainly with European American samples in the US on attitudinal and behavioral changes, respectively). Applying this work to parental socialization, it may take more than attitude egalitarianism for parents to gear their youths’ activities to certain directions. In fact, in support of Hypotheses 4.1 and 4.2, gender atypical behaviors (i.e., girls and boys exhibiting more similar involvement in household duties and girls spending more similar amounts of time with mothers and fathers) were only observed in families in which parents had both an egalitarian division of household labor and egalitarian gender role attitudes. Despite what they might have been told by their parents about gender roles, youths in the congruent labor group seemed to be more inclined to model what they saw in the family (i.e., women did more housework than did men) and to spend more time with parents of their own gender. Although social learning theorists have long proposed that incongruence between what is modeled and what is taught by the instructor may undermine the adherence of the learner (Bussey & Bandura, 1999), parents’ roles as instructors and opportunity providers in general, and the potentially contradictory influences as instructors versus role models and opportunity providers, continue to be neglected in the family and developmental literature (Parke & Buriel, 2006). A direction for future studies will be to measure other facets of parental gender socialization and examine their links with youth gender outcomes.

It is worth noting that, although parents’ gendered practices and beliefs constitute part of the larger family context that shapes youth development, youths also play an active role in constructing their environments (García Coll et al., 1996). Ayala's (2006) and Denner and Dunbar's (2004) qualitative studies clearly showed that mother-daughter interactions in Mexican American families in the US were reciprocal: As mothers engaged their daughters in household responsibilities, daughters also challenged their mothers to change family gender norms. One way to interpret our findings, for example, is that gender atypical youths introduced new gender dynamics to their parents. Another direction for future studies will be to examine youths’ initiatives to influence their parents’ gendered characteristics.

Because migration entails many transitions and may be accompanied by an unwelcoming host environment, ethnic minorities are more likely to live in poverty and experience adjustment challenges. Not surprisingly, much of the existing work on ethnic minority youths in the US concentrates on problematic family processes and negative individual outcomes (McLoyd et al., 2000; Vega, 1990). Given that an emphasis on risks and pathology reinforces negative stereotypes, some researchers have called for investigation of resilience and well-being that arise from migratory or ethnic experiences (Suárez-Orozco & Qin, 2006). Examination of gender dynamics and socialization among ethnic minorities through the lens of normative family processes also contributes to this effort. Because gender operates as a major organizing force in the lives of ethnic minorities (Suárez-Orozco & Qin, 2006), continued research on gender and family dynamics will shed light on the complex confluence of gender, migration, and adaptation.

Limitations and Conclusions

This study was not without limitations. First, cluster analysis, as a preliminary step in our study to form groups characterized by congruence and incongruence between parents’ housework allocation and gender ideologies, is exploratory in nature. Although the three identified patterns were consistent with multiple theories (Coverman, 1985; Huston & Burgess, 1979; Ruble et al., 2006; West & Zimmerman, 1987) and prior research (Crompton & Lyonette, 2006), the cluster structure should be replicated in other samples before conclusions can be drawn about the division of household labor and gender role attitudes in Mexican American families. A related issue about generalizability is that our sample only included two-parent Mexican American families with employed fathers, and thus our results may not be able to capture the gender dynamics in other family structures (e.g., single-parent, mother-headed). Of particular interest here is recent evidence, based on nationally representative samples from Australia and the US, that husbands who are unemployed or fail to fulfill the provider role actually contribute less to housework, possibly in an attempt to reaffirm their authority as head of the household (Bittman, England, Sayer, Folbre, & Matheson, 2003). Future research should be directed at examining why and how women and men may “overdo” gender for reasons of compensation when their gender expectations are violated. Second, our cross-sectional design did not allow for analysis of direction of effect. A panel design that captures longitudinal changes in parents’ housework allocation and gender ideologies, family socioeconomic conditions, and cultural orientations, and youths’ gendered characteristics would help to pinpoint the casual relations of these factors.

In face of these limitations, our study's use of a within-family design and its inclusion of social contextual correlates and multiple measures of gender provide new insights into gender research and highlight the importance of contextualizing the study of ethnic minority families. On an ideological level, our findings also contribute to correcting the stereotypes that Latino families are universally traditional in their gender dynamics, that family dynamics among immigrants and ethnic minorities are solely determined by cultural values, and that Mexican American parents in the US invariably socialize their children in gender stereotypical ways.

References

- Ajzen I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:27–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala J. Confianza, consejos, and contradicciones: Gender and sexuality lessons between Latina adolescent daughters and mothers. In: Denner J, Guzman BL, editors. Latina girls: Voices of adolescent strengths in the United States. University Press; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bittman M, England P, Sayer L, Folbre N, Matheson G. When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;109:186–214. doi:10.1086/378341. [Google Scholar]

- Blair SL, Lichter DT. Measuring the division of household labor: Gender segregation of housework among American couples. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12:91–113. doi: 10.1177/019251391012001007. [Google Scholar]

- Bohner G, Dickel N. Attitudes and attitude change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;62:391–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review. 1999;106:676–713. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.676. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1208–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S, Valdez E. Reluctant compliance: Work/family role allocation in dual-earner Chicano families. In: Hood JC, editor. Men, work and, family. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Coverman S. Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labor. Sociological Quarterly. 1985;26:81–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1985.tb00217.x. [Google Scholar]

- Chatard A, Selimbegovic L. The impact of higher education on egalitarian attitudes and values: Contextual and cultural determinants. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007;1:541–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00024.x. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton R, Lyonette C. Work-life ‘balance’ in Europe. Acta Sociologica. 2006;49:379–393. doi: 10.1177/00016993060716800. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M. Parental influences on the gendered division of housework. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:184–203. doi:10.2307/2657414. [Google Scholar]

- Denner J, Dunbar N. Negotiating femininity: Power and strategies of Mexican American girls. Sex Roles. 2004;50:301–314. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000018887.04206.d0. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CG, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, García HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi: 0.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Division of household labor, strain, and depressive symptoms among Mexican Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1990;14:103–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1990.tb00007.x. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein TN. National context, family satisfaction, and fairness in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:1039–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00651.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LW, Kloska DD. Parents’ gender-based attitudes toward marital roles and child rearing: Development and validation of new measures. Sex Roles. 1995;32:273–295. doi: 10.1007/BF01544598. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Burgess RL. Social exchange in developing relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. Academic; New York, NY: 1979. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii-Kuntz M, Coltrane S. Predicting the sharing of household labor: Are parenting and house- work distinct? Sociological Perspectives. 1992;35:629–647. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/pss/1389302. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroska A, Elman C. Change in attitudes about employed mothers: Exposure, interests, and gender ideology discrepancies. Social Science Research. 2009;38:366–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance-Grzela M, Bouchard G. Why do women do the lion's share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles. 2010;63:767–780. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9797-z. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Hispanic families: Stability and change. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:381–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131655. [Google Scholar]

- Marks JL, Lam CB, McHale SM. Family patterns of gender role attitudes. Sex Roles. 2009;61:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9619-3. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9619-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Whiteman SD. The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2003;12:125–148. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00225. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01070.x. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. III. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Wiley; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 429–504. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen CA. Migration and gender among Mexican Women. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:606–632. doi: 10.1177/000312240507000404. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto KM, Coltrane S. Division of labor in Mexican origin and Anglo families: Structure and culture. Sex Roles. 2009;60:482–495. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9549-5. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers K. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath KV, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2008. pp. 170–222. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai L. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles. 2004;50:287–899. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000018886.58945.06. [Google Scholar]

- Raley S, Mattingly MJ, Bianchi SM. How dual are dual income couples? Documentary change from 1970 to 2001. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00230.x. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL, Berenbaum S. Gender development. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. 6th ed. Wiley; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 858–932. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Qin DB. Gendered perspectives in psychology: Immigrant origin youth. International Migration Review. 2006;40:165–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00007.x. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Walker AJ. Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:845–871. doi:10.2307/353201. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review. 1989;96:506–520. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.506. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau Tables of the Hispanic Population in the US. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hispanic/tables.html.

- Vega W. Hispanic families in the 1980s: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1015–1024. doi: 10.2307/353316. [Google Scholar]

- von Eye A, Bogat GA. Person-oriented and variable-oriented research: Concepts, results, and development. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:390–420. doi: 10.1027/0044-3409/a000024. [Google Scholar]

- West C, Zimmerman DH. Doing gender. Gender and Society. 1987;1:125–151. doi:10.1177/0891243287001002002. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman S, Loken E. Comparing analytic techniques to classify dyadic relationships: An example using siblings. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:370–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00333.x. [Google Scholar]