SUMMARY

The heterotrimeric G protein Gαq is a key regulator of blood pressure, and excess Gαq signaling leads to hypertension. A specific inhibitor of Gαq is the GTPase activating protein (GAP) known as regulator of G protein signaling 2 (RGS2). The molecular basis for how Gαq/11 subunits serve as substrates for RGS proteins and how RGS2 mandates its selectivity for Gαq is poorly understood. In crystal structures of the RGS2-Gαq complex, RGS2 docks to Gαq in a different orientation from that observed in RGS-Gαi/o complexes. Despite its unique pose, RGS2 maintains canonical interactions with the switch regions of Gαq in part because its α6 helix adopts a distinct conformation. We show that RGS2 forms extensive interactions with the α-helical domain of Gαq that contribute to binding affinity and GAP potency. RGS subfamilies that do not serve as GAPs for Gαq are unlikely to form analogous stabilizing interactions.

INTRODUCTION

Activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) catalyze guanine nucleotide exchange on the α subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein Gαβγ. When bound to GTP, the Gα protein binds downstream effectors and thereby alters the concentration of second messengers in the cell. Signaling by Gα·GTP is controlled by the relatively slow intrinsic GTPase activity of Gα proteins, which can be accelerated via interactions with GTPase activating proteins (GAPs). GAP domains for Gα subunits are found in effector enzymes such as phospholipase C-β (PLCβ) (Chidiac and Ross, 1999; Waldo et al., 2010) and in regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins. The catalytic core of RGS proteins, known as the RGS box or the RGS homology (RH) domain, consists of an oblong bundle of nine α helices (α1–α9) (Kimple et al., 2011; Tesmer, 2009). The RH domain engages all three switch regions of Gα (SwI-III) and stabilizes a transition state-like conformation for GTP hydrolysis (Tesmer et al., 1997). One key residue responsible for this activity is a nearly invariant asparagine residue in the α5-α6 loop of the domain (e.g., RGS2-Asn149) (Natochin et al., 1998; Posner et al., 1999; Srinivasa et al., 1998).

There are many mechanisms that underlie the selectivity of an RGS protein for a given heterotrimeric G protein signaling pathway (Xie and Palmer, 2007). However, the selectivity of an RH domain for a given Gα subunit is strongly dictated by their specific interactions (Natochin and Artemyev, 1998). About half of the 20 RH domains from RGS proteins found in humans can bind to and serve as GAPs for Gα subunits from both the Gi/o and Gq/11 subfamilies (such as those in the R4 subfamily, which includes RGS4), whereas some are specific for Gi/o (such as those in the R7 subfamily, which include RGS6, -7, -9, and -11; and those in the R12 subfamily, which include RGS10, -12, and -14) (Soundararajan et al., 2008). RGS2, an R4 subfamily member, exhibits marked selectivity for Gαq in vitro (Heximer et al., 1997, 1999) but can serve as a GAP for Gαi in membrane-reconstituted systems (Cladman and Chidiac, 2002; Ingi et al., 1998). Mice lacking RGS2 have high blood pressure (Heximer et al., 2003), one of a number of observations consistent with RGS2 being a key physiological regulator of Gαq (Tsang et al., 2010). The inability of the RGS2 RH domain to serve as an efficient GAP for Gαi/o in vitro stems from differences in three interfacial residues that are invariant in other RGS proteins: Cys106, Asn184, and Glu191 (Ser85, Asp163, and Lys170 in rat RGS4). The C106S/N184D/E191K mutant of RGS2 (referred to hereinafter as RGS2SDK) rescues the ability of RGS2 to serve as a GAP for Gαo (Heximer et al., 1999). Structural analysis shows that RGS2SDK binds to Gαi subunits in much the same way as has been observed for other RGS-Gαi/o subunit complexes (Kimple et al., 2009). Thus, it was presumed that packing incompatibilities created by RGS2-Cys106 and -Asn184 with SwI lead to loss of binding affinity for Gαi/o subunits. However, Gαq and Gαi/o have very similar switch regions, and it is not clear how Gαq tolerates the presence of Cys106 and Asn184 in RGS2. Although RGS2SDK-Lys191 was poorly ordered in the RGS2SDK-Gαi/o crystal structure, this position is thought to affect affinity via selective electrostatic interactions with the α-helical domain of Gα. RGS2SDK did not exhibit a serious binding defect with Gαq (Heximer et al., 1999; Kimple et al., 2009), indicating that RGS2-Cys106, -Asn184, and -Glu191 by themselves do not confer a particular ability to recognize Gαq.

At least nine atomic structures of complexes between RGS proteins and Gα subunits have been determined (Slep et al., 2001, 2008; Soundararajan et al., 2008; Tesmer et al., 1997), all involving Gα subunits from the Gαi/o subfamily of G protein α subunits (Gαi1, Gαi3, Gαo, and the Gαt/i1 chimera). Thus, these structures do not provide direct insight into the molecular determinants that dictate how Gαq interacts with RGS proteins (in particular, RGS2). Herein, we describe two crystal structures of the RGS2 RH domain in complex with an N-terminally truncated, constitutively active mutant of Gαq (ΔNGαqR183C). Compared to other RGS-Gαi/o structures, RGS2 adopts a unique orientation as it engages Gαq that creates more extensive inter-actions with the α-helical domain of Gαq. The α6 helix of RGS2 is also shifted by 2–3 Å relative to other RGS domains, allowing RGS2 to maintain canonical interactions with SwIII despite its unique pose. Deleterious effects of site-directed mutation of residues in the interface of RGS2 with the α-helical domain of Gαq demonstrate the importance of this interface in dictating affinity and GAP potency.

RESULTS

Structural Analysis of a Complex between RGS2 and Gαq

Although stoichiometric complexes of the RGS2 RH domain (residues 72–203) and Mg2+·AlF4−-activated Gαq were obtained using a number of different Gαq variants, we were only able to form crystals from a complex using a variant of Gαq in which the N-terminal helix was deleted to reduce conformational heterogeneity, as this region is typically disordered in crystal structures of Gα in the absence of Gβγ. Our best crystals were obtained with the R183C constitutively active variant of this truncated Gαq (ΔNGαqR183C). Mg2+·AlF4−-activated wild-type (WT) and R183C Gαq have similar affinities for RGS2, as measured via a bead-based flow cytometry binding assay (KD = 20 ± 9 nM, n = 3, and 22 ± 9 nM, n = 3, respectively), consistent with the fact that the Gαq-Arg183 side chain neither interacts with the RH domain nor hinders the formation of the GDP-AlF4− transition state. Indeed, GαqR183C was previously shown to be an efficient substrate for RGS proteins (Chidiac and Ross, 1999), as was the analogous R178C variant of Gαi1 (Berman et al., 1996).

Initial crystals diffracted to only 7.4 Å (crystal form A, space group C2) but were improved by the addition of either NiCl2 or CoCl2, which generated a different crystal form (crystal form B, space group P41212) that diffracted anisotropically to maximum spacings of 2.7 Å (Table 1). Initial phases for each structure were provided by molecular replacement (Figures 1A and 1B). Both crystal forms involve a hydrophobic crystal contact involving the α2 helix (SwII) and the α3-β5 loop of a 2-fold related Gα subunit. In crystal form A, a dimer interface is formed by the αB and αC helices of the α-helical domain of Gαq to form a four-helix bundle (Figure 1A). This contact is ablated in crystal form B due to the coordination of Co2+ by His105 and His109 in the αB helix (Figure 1B). The RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C complex from crystal form B superimposes with a root-mean-squared distance (RMSD) of 0.4 Å for 445 Cα carbons from either complex in the asymmetric unit of crystal form A, indicating that the binding of Co2+ does not affect the overall conformation of the complex. The RGS2-ΔNGαq complex was also crystallized under the conditions of crystal form B, but these crystals diffracted poorly (anisotropic with maximum spacings of 4 Å). Although this structure was not refined to completion, it demonstrated that mutations within GαqR183C do not grossly affect the conformation of the complex (RMSD = 0.4 Å with RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C).

Table 1.

Crystallographic Data Statistics

| Crystal Form A | Crystal Form B (CoCl2) | |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Source | APS 21-ID-G | APS 21-ID-D |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9786 | 1.0782 |

| Dmin (Å) | 7.40 (7.53–7.40) | 2.7 (2.75–2.70) |

| Space group | C2 | P41212 |

| a = 140 | a = 60.2 | |

| b = 125 | b = 60.2 | |

| c = 97.2 | c = 346 | |

| β = 124°; α = γ = 90° | α = β = γ = 90° | |

| No. of crystals | 1 | 1 |

| Unique reflections | 1,820 (78) | 11,782 (189) |

| Average multiplicity | 3.7 (3.7) | 4.0 (2.7) |

| Rsym (%) | 15.6 (51.8) | 6.5 (44.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.3 (100.0) | 64.0 (21.4)a |

| <I>/<σI> | 9.1 (2.5) | 24.9 (1.6) |

| Refinement resolution | 20.0–7.4 (7.57–7.40) | 30.0–2.71 (2.78–2.71) |

| Total reflections used | 7,811 (87) | 11,078 (199) |

| No. of Atoms/<B Factor> (Å2)b | ||

| Protein atoms | 7,318/141 | 3,696/111 |

| Nonprotein atoms | 74/77 | 66/96 |

| Rmsds | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| MolProbity Analysis | ||

| Clashscore | 18.2 (97th pctl) | 10.3 (98th pctl) |

| Protein geometry score | 2.4 (99th pctl) | 2.3 (94th pctl) |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 2.1 | 3.4 |

| Cβ deviations > 0.25Å | 0 | 0 |

| Res. with bad bonds (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Res. with bad angles (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.23 | 0.45 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 93.3 | 94.8 |

| Rwork (%) | 15.8 (27.1) | 19.0 (33.3) |

| Rfree (%) | 22.0 (NA) | 25.2 (37.0) |

| PDB Entry | 4EKC | 4EKD |

rmsds, root-mean-square deviations; pctl, percentile; Res., residues; NA, not applicable (there were no reflections used for Rfree in the highest resolution shell).

Due to severe anisotropy of the diffraction pattern, the CoCl2 data set was elliptically truncated to 3.5 Å spacings along a* and b*, and to 2.7 Å spacings along c* before scaling. Overall completeness was 91.9% (92.9% in the highest resolution shell) before truncation.

Includes translation/libration/screw (TLS) vibrational component.

Figure 1. Structural Analysis of RGS2-Gα Subunit Complexes.

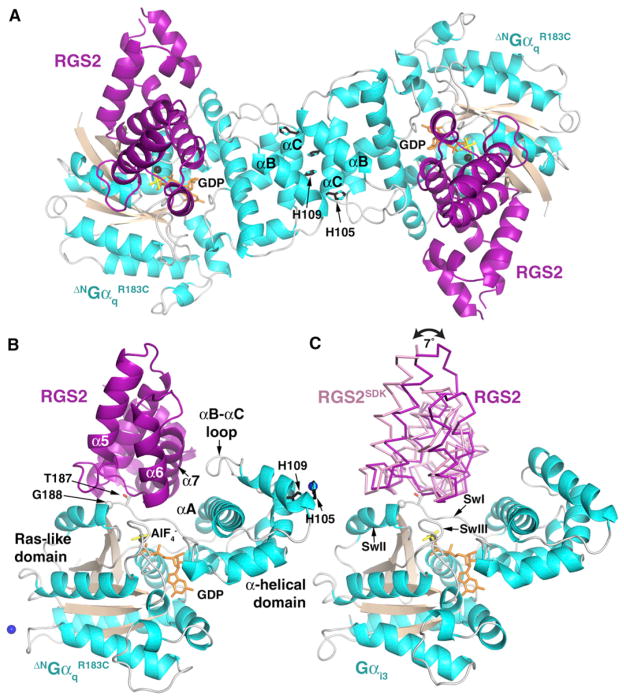

(A) In crystal form A, the RGS2-ΔNG αqR183C complex crystallized as a dimer mediated by the αB and αC helices of the α-helical domain. The side chains of Gαq-His105 and -His109, which coordinate Co2+ in crystal from B, are buried in this interface. RGS2 is shown in purple, and Gαq is shown with cyan helices and tan β strands. GDP and AlF4− are shown as orange and yellow sticks, respectively, and Mg2+ is shown as black spheres.

(B) The α7 helix of RGS2 makes extensive contacts with αA and the αB-αC loop of ΔNGαqR183C. The structure shown is that of crystal form B, which was grown in the presence of Co2+ (blue spheres).

(C) RGS2 binds to ΔNGαqR183C in a different orientation than RGS2SDK to Gαi3 (PDB code 2V4Z) (Kimple et al., 2009). RGS2 and RGS2SDK are shown as purple and pink ribbons, respectively. RGS2 was positioned by aligning ΔNGαqR183C (data not shown) with Gαi3 in the 2V4Z structure. The two RH domains differ in orientation by 7°, related by an axis that passes through the peptide bond between Gαi3-Thr182 and -Gly183 (Gαq-Thr187 and -Gly188); see (B). Consequently, RGS2 is tilted toward the α-helical domain relative to RGS2SDK, and the structurally distinct αB-αC loop of Gαi3 does not come as close to α7 of the RH domain. The overall structure of RGS2 bound to Gαq is more similar to apo RGS2 than RGS2SDK bound to Gαi3.

Superposition of Gαq in the RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C complex with Gαi in either the RGS4-Gαi1 or the RGS2SDK-Gαi3 complex reveals that the RH domain of RGS2 is rotated by 7° relative to that of RGS4 or RGS2SDK around an axis roughly colinear with a vector joining the Gαq-Gly207 and Gly208 Cα carbons in SwII (Figures 1B and 1C) and passing through the backbone between Gαq-Thr187 and Gly188 in SwI. Thr187 and Gly188 are well established as being critical for interactions with RGS proteins (Day et al., 2004; DiBello et al., 1998; Lan et al., 1998) and serve as an apparent pivot point relating WT RGS2 to RGS2SDK when bound to ΔNGαqR183C or Gαi3, respectively (Figure 1C). One consequence of this rotation is that the α7 helix of the RGS2 RH domain is brought into close contact with αA and the αB-αC loop of the α-helical domain of Gαq, a region that is structurally distinct between Gαq and Gαi subfamilies (Figures 1B and 1C). This interaction accounts for most of the additional 600 Å2 of accessible surface area buried in the RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C complex relative to the RGS2SDK-Gαi3 complex.

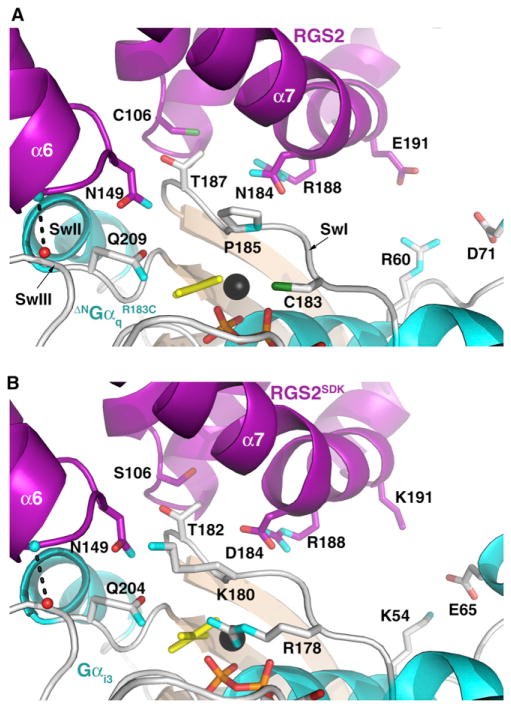

Despite the distinct pose of RGS2 on Gαq, the interactions of RGS2 with the switch regions of Gαq are similar to those observed in other RGS-Gα complexes, consistent with there being a conserved mechanism used by RGS proteins to accelerate GTP hydrolysis (Figures 2A and 2B). The side chain of Gαq-Thr187 in SwI docks in a shallow, highly conserved pocket on the RH domain, Gαq-Gln209 in SwII interacts with RGS2-Asn149, and SwIII interacts with residues at the N terminus of α6 in the RH domain, including a canonical backbone-backbone intermolecular hydrogen bond. The side chain of RGS2-Cys106 is rotated by ~35° relative to that of RGS2SDK-Ser106, likely to help accommodate the larger size of the sulfhydryl group. We speculate that, because this group packs next to Gαq-Thr187 (at the pivot point), it helps promote the change in the overall pose of the RGS2 RH domain relative to that of other RGS-Gα complexes (Figures 1B and 1C). RGS2-Asn184, which also contacts Gαq-Thr187, is conserved as an aspartic acid in other RGS proteins where it forms a specific hydrogen bond with SwI and a salt bridge with RGS2-Arg188. However, in the RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C complex, RGS2-Asn184 only makes van der Waals interactions with SwI and RGS2-Arg188 and thereby also likely contributes to the change in RH domain orientation. RGS2-Glu191 has been proposed to form an unfavorable electrostatic interaction with Gαi-Glu65, thereby contributing to the selectivity of RGS2 for Gαq (Heximer et al., 1999). In our crystal structure, the RGS2-Glu191 side chain lacks electron density, but when modeled in a favorable extended conformation, it makes no obvious contacts with Gαq, with the closest side chain being that of Gαq-Arg60 (~5.0 Å away). The side chain would be at least 5.5 Å away from Gαq-Asp71 (analogous to Gαi-Glu65). Thus, Gαq may be insensitive to the identity of the amino acid found in RH domains at positions analogous to RGS2-Glu191. The tilted pose of RGS2 on Gαq does not occlude the binding of proteins (i.e., GRK2 and p63RhoGEF) known to form ternary complexes by interacting with the effector-binding site of Gαq (Shankaranarayanan et al., 2008).

Figure 2. Unique Residues in the Interface between RGS2 and SwI of Gαq Likely Induce a Change in the Orientation of the RH Domain.

(A) The RGS2-ΔNGαqR183 switch region interface. As in other RGS protein complexes (see panel B), the RH domain forms canonical interactions with all three switch regions of Gαq: Thr187 in SwI binds in a shallow pocket next to Cys106, Gln209 interacts with Asn149 in the α5-α6 loop of the RH domain, and a backbone carbonyl (red sphere)-backbone amide (cyan sphere) hydrogen bond (dashed line) is formed with SwIII. To maintain the SwIII interaction, the α6 helix region of RGS2 adopts a distinct conformation from that observed in other characterized RGS-Gα complexes. The side chain of Glu191 makes no direct interaction with Gαq. The coloring scheme is identical to that shown in Figure 1.

(B) The RGS2SDK-Gαi3 switch region interface. The positions occupied by Cys106, Asn184, and Glu191 in (A) are conserved as serine, aspartate, and lysine, respectively, in other RGS proteins, as portrayed by the RGS2SDK mutant. Arg178, which helps coordinate AlF4− (yellow sticks), corresponds to the R183C mutation shown in (A). Another prominent difference between Gαq and Gαi3 is Pro185, see (A), and Lys180, see (B). The Lys191 side chain was partially disordered in the structure but is poised to make favorable electrostatic interactions with the side chain of Gαi-Glu65.

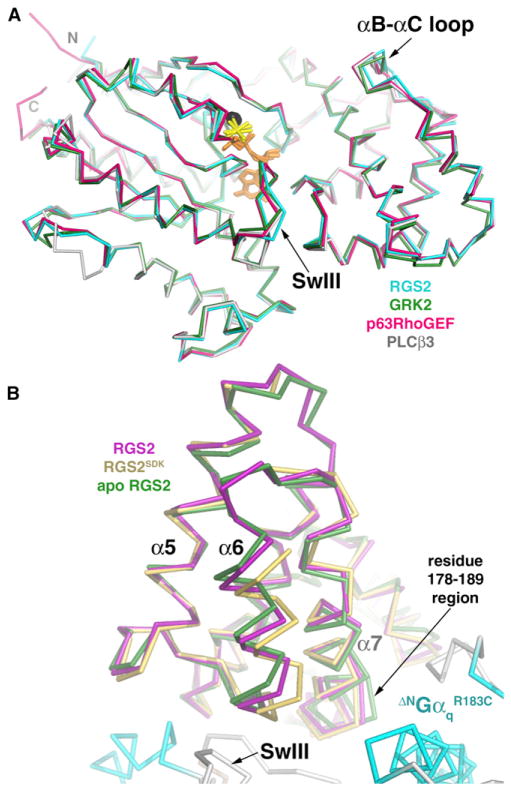

RGS2 binding does not induce a significant overall conformational change in Gαq (Figure 3A). Indeed, previously determined structures of Gαq in complex with G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) (Tesmer et al., 2005), p63RhoGEF (Lutz et al., 2007), and phospholipase Cβ 3 (PLCβ3) (Lyon et al., 2013; Waldo et al., 2010) superimpose similarly with that of RGS2-bound Gαq with an RMSD of 0.7–0.8 Å for 317 Cα atoms (0.4–0.5 Å for 270–286 Cα atoms when omitting flexible loops). However, two loops do seem to change conformation upon RGS2 binding: residues 117–127 in the αB-αC loop, which interact with the α7 helix of RGS2, and residues 242–245 in SwIII, which do not directly contact the RH domain but may alter their conformation as a consequence of the contact formed between the α6 helix of RGS2 and SwIII (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 3. Conformational Differences Exhibited by Gαq and RGS2.

(A) Cα superposition (omitting flexible loops) of AlF4−-activated Gαq in complex with RGS2 (indicated in cyan in this study), GRK2 (green in Tesmer et al., 2005), p63RhoGEF (magenta in Lutz et al., 2007), and PLCβ3 (gray in Waldo et al., 2010). The binding of RGS2 influences the conformation of the αB-αC loop and SwIII, which exhibit structural differences among all the models.

(B) Comparison of the α6 helix region from three different structures of RGS2. Gαq-bound RGS2 (indicated in magenta in this study) is most similar to apo RGS2 (PDB entry 2AF0; indicated in green in Soundararajan et al., 2008) in that their α6 helices adopt a distinct conformation from those of other R4 family members, as typified by the structure of RGS2SDK (PDB entry 2V4Z; yellow in Kimple et al., 2009). To generate this figure, the structures of apo-RGS2 and RGS2SDK were superimposed on ΔNGαqR183C-bound RGS2, omitting the α6 region of the RH domain. The ΔNGαqR183C subunit is colored as in Figure 1.

Comparison of the structure of apo RGS2 (Soundararajan et al., 2008) with that of Gαq-bound RGS2 reveals little difference in the conformation for most of the RH domain: RGS2 helices α3–8 (residues 96–192) have an RMSD of 0.65 Å for 97 Cα atoms. Residues 178–189 at the end of α7 in apo RGS2 adopt a significantly different conformation from those of Gαq-bound RGS2 and Gαi3-bound RGS2SDK, likely because this region is constrained by contacts with SwI in Gα complexes (Figure 3B). Comparison of Gαq-bound RGS2 with Gαi3-bound RGS2SDK reveals a significant conformational difference in the C-terminal end of the α5-α6 loop and the α6 helix of RGS2 (residues 150–171). If this region is excluded, the Gαq and Gαi3-bound RH domains of RGS2 superimpose well, with an RMSD of 0.5 Å. The fact that the α6 helix of apo RGS2 is more similar in conformation to Gαq-bound RGS2 than it is to Gαi3-bound RGS2SDK (Figure 3B) suggests that the RH domain of RGS2 has evolved a distinct conformation that complements the unique way this RH domain binds to Gαq. In contrast, Gαi3-bound RGS2SDK adopts an overall conformation that is most similar to other structurally characterized R4 RGS proteins, such as RGS4. Because RGS2-Cys106, -Asn184, and -Glu191 are not directly involved in the packing of α6 within the RH domain, the conformation of the α6 region in Gαi3-bound RGS2SDK is probably induced by its interaction with Gαi3. Notably, the α6 helix of RGS2SDK is poorly ordered relative to apo RGS2 and RGS2 in complex with ΔNGαqR183C, consistent with a nonnative conformation.

Functional Assessment of Interactions between RGS2 and Gαq

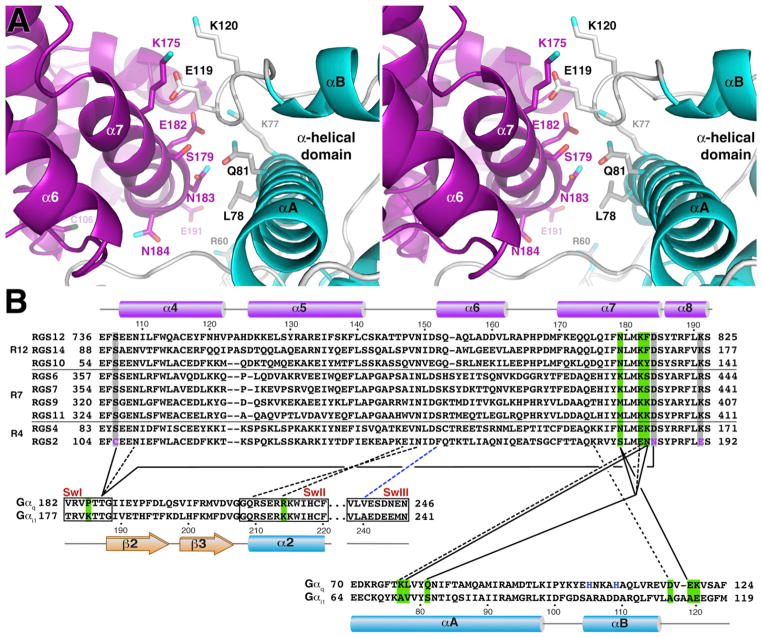

The additional interactions formed between the RH domain of RGS2 and Gαq likely help promote the ability of RGS2 to serve as a GAP for Gαq. In the interface with the α-helical domain, RGS2-Lys175, Ser179, Glu182, and Asn183 in α7 interact with Gαq-Leu78 and Gln81 from the αA helix and Gαq-Glu119 from the αB-αC loop (Figure 4A). Ser179 and Asn183 are unique to RGS2, whereas Leu78, Gln81, Glu119, and Lys120 are unique to Gαq (Figure 4B). In the SwII interface, Gαq-Arg214 potentially makes selective interactions with the backbone in the α5-α6 loop of RGS2, as it is conserved as a shorter lysine residue in Gαi/o subunits (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Contacts between Gαq and RGS2.

(A) Stereo view of the interface between RGS2 and the α-helical domain of ΔNGαqR183C, highlighting residues that were selected for site-directed mutagenesis and functional analysis. Coloring scheme is identical to that in Figure 1.

(B) Sequence conservation of interacting residues in RGS2 and Gαq. Only select regions of each RH domain and Gα subunit are shown. Solid lines indicate van der Waals contacts, dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds or salt bridges, and the blue dashed line indicates a backbone-backbone hydrogen bond. For clarity, not all intersubunit contacts are shown. Potential interactions of Glu191 are not shown because the structure predicts that its side chain will not directly interact with the α-helical domain of Gαq. Grey backgrounds highlight the conservation of three contact residues that are unique to RGS2: Cys106, Asn184, and Glu191 (purple). Green highlights indicate positions that may dictate selectivity among RGS proteins or Gαq/Gαi/o subunits. The three switch regions (SwI–III) of Gα are indicated by black boxes. The two blue positions in αB of Gαq are histidines observed to coordinate Co2+ in crystal form B. The secondary structure and numbering above the RH domain sequences is that of RGS2, and those below the Gα sequences are for Gαq. The numbers at the beginning and end of each sequence correspond to the residue number of each individual protein sequence. All members of the R12 and R7 subfamilies are shown, but only RGS4 and RGS2 are shown for the R4 subfamily. The Swiss-Prot accession numbers for the sequences are as follows: human RGS2, P41220; rat RGS4, P49799.1; human RGS6, P49758; human RGS7, P49802; bovine RGS9, O46469; human RGS10, O43665; human RGS11, O94810; human RGS12, O14924; human RGS14, O43566; rat Gαi1, P10824; mouse Gαq, P21279.

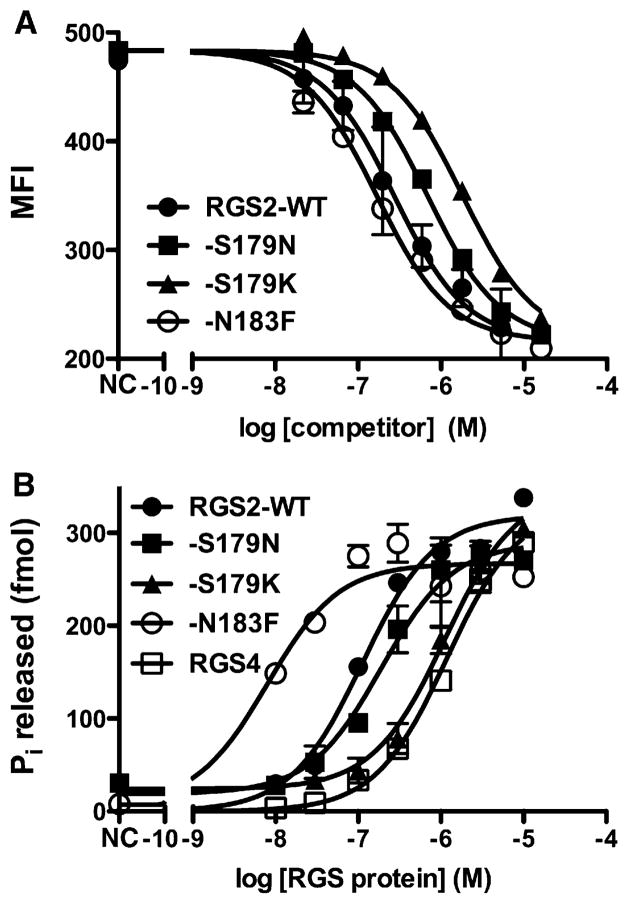

If these contacts are important for RGS2 function, then their disruption by site-directed mutagenesis should lead to decreased affinity and GAP potency for Gαq. To measure relative affinity, we performed an assay in which we titrated each RGS2 variant against fluorescently labeled full-length RGS2 bound to AlF4−-activated Gαq attached to beads, which were then analyzed by flow cytometry (Table 2; Figure 5A). We also measured GAP potency, which is thought to reflect indirectly the affinity of the interaction between the RGS protein and Gα subunit (Srinivasa et al., 1998), in the background of the GTPase-deficient yet RGS-responsive mutant of Gαq, GαqR183C (Chidiac and Ross, 1999). WT Gαq cannot be assessed in this assay format because Gαq hydrolyzes GTP faster than it can be loaded with GTP (Chidiac et al., 1999). All RGS2 and Gαq variants were shown to have similar purity and concentration as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis (data not shown). Because all RGS2 mutants exhibited similar melting points to WT (Table 2), they are unlikely to exhibit major folding defects.

Table 2.

Characterization of RGS Domains and Their Interactions with Gαq

| RGS Variant | Tm (°) | IC50 in μM | Fold Increase Over WT | Log EC50 in nM (n) | Fold Increase Over WT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGS2-wt | 43.5 ± 0.1 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 1 | 2.1 ± 0.03 (20) | 1 |

| -K175A | 45.0 ± 0.4 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 2 | 2.4 ± 0.03 (4) | 2 |

| -S179D | 45.0 ± 0.2 | 16.0 ± 4 | 60 | 3.8 ± 0.26 (3) | 50 |

| -S179K | 45.0 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 13 | 3.0 ± 0.07 (5) | 8 |

| -S179M | 45.2 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.09 (5) | 0.4 |

| -S179N | 43.0 ± 0.2 | 0.69 ± 0.1 | 2.5 | 2.3 ± 0.06 (7) | 2 |

| -E182A | 49.7 ± 0.5 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 1 | 2.2 ± 0.05 (4) | 1 |

| -N183A | 48.8 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 5.5 | 2.3 ± 0.03 (4) | 2 |

| -N183F | 41.7 ± 0.1 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.04 (5) | 0.1 |

| -N183K | 49.5 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 1 | 26 | 3.0 ± 0.03 (4) | 8 |

| RGS4-wt | – | – | – | 3.1 ± 0.05 (5) | 10 |

The melting temperatures (Tm) are derived from two separate experiments measured in triplicate. IC50 values ± SEM from a bead-based flow cytometry competition assay were determined from three to five experiments measured in duplicate. For EC50 measurements, single-turnover GTP hydrolysis by His-Gαi/q LONG R183C was measured at 20°C in the presence of various RGS constructs. Seven concentrations of each RGS protein were tested (ranging from 10 nM to 10 μM), and the resulting data were used to generate dose-response curves. The values shown represent means ± SEM of the nonlinear regression fit.

Figure 5. Biochemical Analysis of RGS2 Variants and RGS4.

(A) Substitutions in RGS2 in the interface with the α-helical domain predominantly cause loss of binding affinity, as measured in a bead-based flow cytometry competition assay. Data shown are representative curves from a single experiment, with each data point measured in duplicate. Error bars correspond to the SEM. Data were fit with GraphPad Prism using a three-parameter one-site competition model with shared top and bottom values. For fitted data for all variants, see Table 2. MFI, median fluorescence intensity. NC; no competitor.

(B) Similar changes are observed in the potency of each variant for stimulating GTP hydrolysis of Gαi/qR183C. Data shown are representative curves from a single set of experiments, with each curve measured in either triplicate (RGS2-WT and RGS4) or duplicate (other variants). Error bars correspond to the SEM. Data were fit with a three-parameter one-site competition model. For fitted data for all variants, see Tables 2 and 3.

As anticipated, two of the most important residues from the α7 helix of RGS2 in the interface were RGS2-Asn183 and Ser179. Mutation of RGS2-Asn183 to lysine, the equivalent residue in other R4 subfamily RGS proteins, including RGS4, increased its half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) in the binding competition assay 26-fold and its half maximal effective concentration (EC50) in the GAP assay 8-fold (Figure 5; Table 2). Substitution of RGS2-Asn183 with alanine was also destabilizing, with a 5.5 fold higher IC50 and ~2-fold greater GAP EC50. The RGS2-S179D variant exhibited 60-fold higher binding IC50 and 50-fold higher GAP EC50 (Figure 5; Table 2). Mutation of RGS2-Ser179 to asparagine, the analogous residue in RGS4 (Figure 4B), decreased potency ~2-fold in both assays. RGS2-K175 and RGS2-E182 did not appear to play a significant role in stabilizing the interface because the K175A and E182A mutations had little or no effect on Gαq binding or GAP potency (Table 2).

We were not able to detect as deleterious effects when interfacial residues of Gαq were mutated. For these experiments, variants of Gαq were created in the background of GαqR183C and evaluated for their response to RGS2 (Table 3). Our most profound effect was a surprising 3-fold lower (more potent) EC50 for the Gαq-E119A/K120A mutant. Gαq-L78V and Q81S and R214K mutations were created to change these positions into their equivalents in Gαi/o subunits (Figure 4B), but these changes had subtle or no effects on their GAP response to RGS2.

Table 3.

RGS2-Mediated GAP Activity on Variants of Gαq

| Gαq Variant | LogEC50 in nM (n) | Fold Increase |

|---|---|---|

| R183C | 2.1 ± 0.03 (20) | 1 |

| R183C/L78V | 2.2 ± 0.05 (9) | 1 |

| R183C/Q81S | 2.4 ± 0.04 (4) | 2 |

| R183C/E119A/K120A | 1.5 ± 0.06 (7) | 0.3 |

| R183C/R214K | 2.0 ± 0.04 (3) | 1 |

Single-turnover GTP hydrolysis by several variants of His-Gαi/q R183C that additionally bear the indicated mutation(s). Hydrolysis was measured at 20°C and in the presence of six concentrations of wild-type RGS2 (10 nM – 3 μM). The values shown represent means ± SEM of the nonlinear regression fit.

Some RGS subfamilies, such as R7 and R12, appear to be specific for Gαi/o subunits (Cho et al., 2000; Soundararajan et al., 2008). With the caveat that these RH domains may dock to Gαq more like RGS4 docks to Gαi, we tested whether substitution of R7 or R12 subfamily-specific residues in the interface formed with the α-helical domain of Gαq could select against Gαq subfamily members. In support of this approach, RGS2 is a more potent GAP than RGS4 for Gαq, with calculated EC50 values of 120 nM and 1.3 μM, respectively (Figure 5B; Table 2); and the RGS2-N183K and RGS2-S179N substitutions, which converted these residues to their equivalents in RGS4 (Figure 4B), individually reduced potency in both competition binding and GAP assays. However, mutation of RGS2-Asn183 to phenylalanine, which is found at this position in RGS12 and RGS14 (Figure 4B), produced a 2-fold more potent binding IC50 and 10-fold more potent GAP EC50 (Figure 5; Table 2). Conversion of RGS2-Ser179 to lysine or methionine, which are found at this position in R7 family members (Figure 4B), generated mixed results. S179K exhibited a severe defect in competition binding and in GAP response (13- and 8-fold, respectively), but S179M was about as stabilizing as RGS2-N183F. Therefore, with the exception of the S179K mutation, the residues we tested in α7 cannot alone account for the R7 and R12 subfamily member selectivity against Gαq (Figure 5B; Table 2). Instead, these results indicate that the introduction of apolar side chains into the interface with the α-helical domain of Gαq (i.e., RGS2-S179M, -S183F, or Gαq-E119A/K120A) generally increases affinity and GAP potency, whereas introduction of buried charge (i.e., RGS2-S179D, -S179K) is greatly destabilizing.

DISCUSSION

There can be many mechanisms for dictating the selectivity of an RGS protein for a given heterotrimeric G protein pathway, including coexpression, interactions mediated by domains other than the RH domain, and positive or negative allosteric regulation of GAP activity mediated by the Gα effector (Xie and Palmer, 2007). For example, although other RGS proteins are found in photoreceptors, RGS9-1 is required for proper termination of phototransduction by activated Gαt. RGS9-1 is expressed only in rod and cone cells (Cowan et al., 1998); is localized to rod outer segment membranes via the interaction of its DEP domain with RGS9-1-anchoring protein (Hu et al., 2003; Martemyanov et al., 2003), which itself is expressed only in the retina (Hu and Wensel, 2002); and is most active when Gαt is bound to its effector target, the inhibitory subunit of cGMP phosphodiesterase (He et al., 1998). Similarly, the selectivity of RGS2 for Gαq in vivo can be attributed to a number of mechanisms, including a unique mode of membrane binding (Gu et al., 2007) and direct interactions with Gq-coupled receptors (Bernstein et al., 2004; Hague et al., 2005). However, the specific contacts formed between the RGS2 RH domain and Gα subunits are still undoubtedly important for dictating GAP potency and, consequently, likely determine if additional interactions are required before GAP activity can be measured (e.g., on Gαi subunits; Ingi et al., 1998).

The two independent crystal structures of the RGS2 RH domain in complex with ΔNGαqR183C, one with two copies of the complex in the asymmetric unit (Figures 1A and 1B; Table 1), together demonstrate that RGS2 binds to Gαq in a distinct orientation from that observed in all nine other reported RGS protein complexes with Gαi/o subfamily members. Because of the distinct conformation of its α6 helical region, RGS2 retains all of the canonical interactions with the switch regions of Gαq, despite the presence of two unique RGS2 residues (Cys106 and Asn184) that pack in the interface with SwI. These residues, along with RGS2-Glu191, prevent RGS2 from binding and serving as an efficient GAP for Gαi/o subunits (Heximer et al., 1999; Kimple et al., 2009). The ability of RGS2 to bind efficiently and serve as a GAP for Gαq is facilitated via an extensive contact with the α-helical domain. Substitution of residues in the interface with the α-helical domain, such as RGS2-Ser179 and -Asn183, had significant effects on binding affinity and potency of GAP activity, indicating that this interface is formed in solution and during catalysis. Influence of the α-helical domain on GAP activity has been noted for other RGS proteins, such as in the regulation of Gαt by RGS9 (Skiba et al., 1999). However, due to the unique tilt of RGS2 when bound to Gαq and the longer αB-αC loop of Gαq, the interactions between RGS2 and the α-helical domain of Gαq are more extensive. The region responsible for GAP activity in the RH domain-containing effector PDZ-RhoGEF also recognizes unique features in the α-helical domain of Gα12 subfamily proteins, although the RH domain of this enzyme does not directly contribute to GAP activity (Chen et al., 2008).

Without a structure of another R4 subfamily member in complex with Gαq, we cannot directly determine if the unique orientation of Gαq-bound RGS2 is a consequence of features unique to Gαq. If Gαq is dictating the change in RH domain orientation, it would most likely be mediated by unique side chains in the three switch regions, as the backbone atoms in Gαq and Gαi/o adopt very similar conformations. One such side chain is Pro185 in SwI of Gαq, which is conserved as lysine in Gαi/o subunits. The Gαq-P185K substitution exhibits defects in RGS2 binding (Day et al., 2004), as does the Gαi-K180P mutation in RGS4 binding (Posner et al., 1999). These observations indicate that, in Gαq and Gαi, the native residue at this position is best suited for interacting with RGS2 and RGS4, respectively, consistent with a unique pose in each complex. Other unique Gαq residues that could influence the pose of RGS proteins are Arg214 in SwII, Leu78 and Gln81 in the αA helix, and Glu119 and Lys120 in the αB-αC loop. However, the Gαq-L78V, Q81S, and R214K mutations, which convert these positions to their equivalents in Gαi, had only mild or no effect on RGS2 GAP potency. The Gαq-E119A/K120A double mutant unexpectedly improved potency (Table 3). Therefore, of the interfacial residues unique to the Gαq subfamily, only Gαq-Pro185 is a candidate for being a determinant of selectivity and perhaps docking orientation.

The balance of our data favors the hypothesis that the unique features of RGS2 are primarily responsible for its noncanonical pose when bound to Gαq. RGS2-Cys106 and -Asn184, which are unique to RGS2, are likely the key drivers of the distinct orientation due to differences in their interactions with the side chain of Gαq-Thr187 and the backbone of SwI (Figures 2A and 2B). RGS2-Glu191, the third uniquely conserved residue in the interface, appears too distant to form specific interactions with residues in the α-helical domain. Instead of helping dictate the unique pose, it may simply help RGS2 select against Gαi/o. In addition to the importance of RGS2-Cys106 and -Asn184, our data show that residues unique to RGS2 within the α7 helix make functionally significant and likely selective interactions with the Gαq α-helical domain (Table 2). Finally, we note that, although the α6 region of RGS2 exhibits a unique conformation that allows RGS2 to maintain canonical interactions with SwIII of Gαq (Figure 3B), structural evidence suggests that this region is flexible and can accommodate binding to either Gαi (in the context of RGS2SDK) or Gαq subunits. Therefore, we do not believe it can be the driving force for the unique pose exhibited by Gαq-bound RGS2.

Our results provide a framework by which to interpret existing biochemical data for RGS2 and RGS4 concerning their ability to serve as GAPs for Gαi/o and Gαq in vitro. We predict that RGS4 binds to Gαq in a way that is similar to how it binds to Gαi but with lower potency (Figure 5B) because the interactions of RGS4 with the α-helical domain of Gαq are not as complementary. Similarly, conversion of RGS2 to RGS2SDK does not greatly affect its ability to bind to Gαq (Heximer et al., 1999; Kimple et al., 2009) because RGS2SDK docks to Gαq in a manner similar to RGS4, with its α6 region changing conformation to maintain interactions with SwIII (as in the RGS2SDK-Gαi3 complex; Figure 3B). However, RGS2SDK binds dramatically better to Gαi/o subunits than WT RGS2 because it adopts an RGS4-like pose when bound to Gαi/o (Kimple et al., 2009). In this way, RGS2SDK can better accommodate the side chain of Gαi-Lys180, and the RGS2-E191K substitution creates a favorable salt bridge with Gαi-Glu65 in the α-helical domain. Introduction of the reverse substitutions into RGS4 (i.e., S85C/D163N/K170E, or RGS4CNE) does not enhance its potency against Gαq (Heximer et al., 1999). If RGS4CNE were to adopt an RGS2-like pose on Gαq, we predict that this would result in less complementary interactions with the α-helical domain, consistent with the reductions in potency we noted for the RGS2-S179N and -N183K mutations that convert these positions to their equivalents in RGS4 (Table 2). There is also no evidence that the RGS4 α6 helix region is flexible enough to maintain optimal interactions with SwIII in this pose (Moy et al., 2000). Like RGS2, RGS4CNE fails to serve as a GAP for Gαi/o subunits in single-turnover assays (Heximer et al., 1999). This may not be due to packing “defects” with SwI, per se, but to structural incompatibilities between Gαi/o and RGS2 or RGS4CNE created when adopting an RGS2-like pose. Specifically, Gαi-Lys180 in SwI could become sterically crowded by the RGS α5-α6 loop; the Gαi/o αB-αC loop would not offer as much buried surface area and potentially introduce an electrostatic clash between Gαi-Glu116 and RGS4CNE-Glu161 or RGS2-Glu182; and the α6 region of these RH domains would likely collide with SwIII. The side chains of RGS4CNE-Glu170 and RGS2-Glu191 would be ~5 Å from that of Gαi-Glu65 in this complex. Although this potentially generates electrostatic repulsion, it seems unlikely to be a major factor in solution at physiological ionic strength, especially considering the flexibility of these residues. It remains possible that these residues are in closer proximity in a pretransition state complex (Heximer et al., 1999).

Therefore, RGS proteins that serve as efficient GAPs for both Gαq and Gαi (e.g., RGS4) are predicted to adopt an RGS4-like pose in complex with Gα while avoiding disruptive interactions with the α-helical domain. If true, then RGS proteins of the R7 and R12 subfamilies could select against Gαq subunits by destabilizing the interface between the α7 helix and the Gαq α-helical domain, as demonstrated in this study by the RGS2-S179D and -S179K substitutions. Docking RGS9, an R7 subfamily member, in an RGS4-like pose on Gαq predicts that RGS9-Lys397 and -Lys398 are incompatible with residues in the αA helix and αB-αC loop of Gαq. Similarly, docking RGS10, an R12 subfamily member, suggests that RGS10-Lys131 is incompatible. Notably, all R7 and R12 subfamily members have lysine conserved at positions equivalent to RGS9-Lys397 and RGS10-Lys131, whereas most R4 members have glutamic acid at this position (e.g., RGS2-Glu182) (Figure 4B). Although loss of the interactions of RGS2-Glu182 was not destabilizing in our assays (i.e., RGS2-E182A; Table 2), a lysine at this position would likely collide with the αB-αC loop of Gαq and electrostatically repel Gαq-Lys77, which is uniquely conserved in the Gαq/11 subfamily (Figure 4B).

In conclusion, our structural and functional analyses indicate that RGS2 and Gαq have evolved a mode of interaction that is unique from other RGS protein Gα complexes, and they provide insight into how selectivity between RGS proteins and Gα subunits is achieved at the level of direct interactions between the RH domain and Gα. There has been much interest in the development of RGS-specific inhibitors as novel targets for the regulation of heterotrimeric G protein signaling cascades (Blazer et al., 2010; Kimple et al., 2011; Sjogren et al., 2010). The unique structure of the RGS2-Gαq complex may allow for the identification of compounds that can selectively stabilize this interaction and ultimately guide the development of novel therapeutics that selectively serve to repress Gαq signaling in pathological conditions such as hypertension.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Proteins

Residues 72–203 spanning the RH domain of RGS2 (RGS272–203) and its site-directed mutants were expressed using the pMalC2H10T vector in E. coli as maltose-binding protein fusions and purified to homogeneity as described previously (Shankaranarayanan et al., 2008). Cleavage of the fusion with tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease leaves the exogenous sequence GEFGS at the amino terminus. Site-directed mutants were introduced using QuikChange (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing over the entire reading frame.

For crystallographic analysis, N-terminal truncations of murine Gαq were expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells. WT and GαqR183C constructs lacking the N terminus (ΔNGαq and ΔNGαqR183C) were generated by PCR amplification of nucleotides encoding residues 36–359 from the respective cDNAs with primers that created 5′ BamHI and 3′ Hind III sites. The BamHI- and Hind III-digested PCR product was subcloned into the baculovirus expression vector, pFastBacHTB, to allow expression of N-terminally hexahistidine-tagged proteins. The ΔNGαqR183C construct contains a six-residue hemagglutinin tag (DVPDYA) inserted for residues 125-ENPYVD-130 (Wilson and Bourne, 1995). These proteins were purified to homogeneity essentially as described for Gαq (Lyon et al., 2011), except that cells were lysed by passage through an Emulsiflex C3 homogenizer at 12,000 psi, and the eluted protein was cleaved overnight by 2% w/w TEV protease in dialysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM guanosine diphosphate [GDP], 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) to remove the hexahistidine tag.

For binding analysis by flow cytometry, murine Gαq (amino acids 7–359) with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag was expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells and purified to homogeneity as previously described (Lyon et al., 2011). The RGS2 binding affinities were measured using the Gαi/q and Gαi/q-R183C proteins. Gαi/q and Gαi/q-R183C are chimeras of Gαq that contain the N-terminal helix of Gαi and were produced as described in Tesmer et al. (2005) and Shankaranarayanan et al. (2008), respectively.

For GAP assays, point mutants of Gαq were generated in the parental baculovirus transfer construct pFastBac-His6-Gαi/q LONG R183C, which directs expression of an N-terminally His6-tagged chimera of rat Gαi1 (amino acids 1–28) fused to mouse Gαq (amino acids 2–359) containing the GTPase-deficient R183C mutation. Gαq point mutants were introduced by overlapping PCR with mutagenic primers. Each construct was confirmed by complete DNA sequencing. His6-Gαi/q LONG R183C and the generated mutant proteins were expressed in High Five cells (Invitrogen) and purified by nickel-NTA (QIAGEN) and Mono Q (GE Healthcare) anion exchange chromatography steps at pH 8.0.

RGS2-Gαq Complex Formation

A 1.2 M excess of RGS272–203 was added to ΔNGαq or ΔNGαqR183C in a solution containing 10 mM NaF, 20 μM AlCl3, and 5 mM MgCl2 and incubated for 30 min on ice. Excess RGS2 was removed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on tandem 10/300 S200 columns (GE Healthcare) in SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM GDP, 20 μM AlCl3, 10 mM NaF). The complex was then concentrated to 5–6 mg ml−1

Crystallization and Cryoprotection

Crystals were grown using hanging-drop vapor diffusion in VDX plates on siliconized glass cover slides (Hampton Research). One microliter of the RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C complex at 5.5 mg ml−1 was combined 1:1 with well solution and suspended over 1 ml of well solution. Crystal form A grew in approximately 1–2 weeks from a well solution containing 10%–20% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, 200 mM NaCl, and 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), pH 5.5, at 4°C. These crystals were needle shaped and diffracted poorly. The best crystals were grown from 17% PEG 3350. Additive Screen HT (Hampton Research) was then used to identify conditions that generated large, single needles (crystal form B), which contained either nickel or cobalt ions and grew in 1–2 days. These crystals belonged to a different space group and diffracted to higher resolution. The best crystals of RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C were grown from 12% PEG 8,000, 15 mM CoCl2, 200 mM NaCl, and 100 mM MES 5.5. To verify that the R183C mutation or the internal hemagglutinin tag of ΔNGαqR183C did not change the overall conformation of the complex, we crystallized the RGS2-ΔNGαq complex using well solutions containing 11% PEG 8000, 17.5 mM CoCl2, 200 mM NaCl, and 100 mM MES 5.5. All crystal forms were harvested in a cryoprotectant solution containing all components of their well solution and SEC buffer plus 30% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol.

Data Collection, Processing, and Model Building

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT) beamline of the Advanced Photon Source. Reflections were integrated, merged, and scaled using HKL2000. Crystals grown with CoCl2 exhibited severe anisotropy, and the most interpretable maps were generated using diffraction data that were elliptically truncated to 3.5 Å spacings along a* and b*, and to 2.7 Å spacings along c* before scaling (Lodowski et al., 2003). Phases were determined using the CCP4 implementation of PHASER (Storoni et al., 2004) using structures of Gαq (Tesmer et al., 2005) and RGS2 (Kimple et al., 2009; Soundararajan et al., 2008) as search models. Modeling was accomplished via successive rounds of TLS and restrained refinement in REFMAC5 for crystal form B, and with only restrained refinement for crystal form A (Winn et al., 2001), and model building in either Coot or O. Refinement of crystal form A included noncrystallographic symmetry restraints for the two complexes in the asymmetric unit. Models were validated using MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010). Atomic coordinates and structure factors for crystal forms A and B are deposited with the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession codes 4EKC and 4EKD, respectively. The RGS2-ΔNGαq complex had unit cell constants similar to that of crystal form B (a = b = 60.6 Å, c = 348 Å ) but diffracted with high mosaicity and anisotropy to maximum spacings of only 4 Å . This crystal form did not offer any additional structural information beyond that obtained for the RGS2-ΔNGαqR183C complex other than to confirm that substitutions in the ΔNGαqR183C variant did not produce major conformational differences. Therefore, this structure was not further refined.

Flow Cytometry Protein-Interaction Assays

The binding affinities for RGS2 and its point mutants and Gαq were measured with a flow-cytometry-based assay (Shankaranarayanan et al., 2008). Murine Gαq (amino acids 7–359) was biotinylated (bGαq) with biotinamidohexanoic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide (Sigma-Aldrich) and attached to SPHERO streptavidin-coated particles (Spherotech). Full-length RGS2 was fluorescently labeled (F-RGS2-FL) with Alexa Fluor-488 carboxylic acid, 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-phenyl ester, 5-isomer (Invitrogen). Binding was performed at 4°C in a buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% lubrol, 2 mM DTT, 1% bovine serum albumin, 10 μM GDP, 10 mM NaF, and 30 μM AlCl3. A background correction was made for equivalent samples in a buffer lacking NaF and AlCl3. In agreement with previous measurements, direct binding between F-RGS2-FL and bGαq yielded a KD ± SEM of 3.3 ± 0.5 nM based on three separate experiments performed in duplicate. We similarly measured the contribution of the R183C mutation to the affinity of Gαq for full-length RGS2 by direct binding analysis in which Gαi/q or its R183C equivalent was biotinylated and attached to beads. The affinity of truncated RGS272–203 and its point mutants for Gαq was determined by mixing F-RGS2-FL at its KD (3 nM) with varying concentrations of unlabeled protein competitor before addition of bead-bound bGαq. Samples were loaded through a Hypercyt (Intellicyt Corporation) to measure the decreased bead-associated median fluorescence intensity on an Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer. At least three independent experiments of duplicate samples were analyzed by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 5.0a.

Thermofluor Analysis

To establish that the site-directed mutants made in RGS272–203 scaffold were properly folded, their melting profiles were analyzed using the fluorescent dye 1-anilinonapthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS), which binds with high affinity to hydrophobic surfaces that are exposed upon protein thermal denaturation. RGS2 samples (0.2 mg ml−1) were prepared in 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 100 mM ANS and overlayed with silicone oil. Using a Thermofluor 384-well plate reader (Johnson & Johnson), samples were heated from 15–25°C to 80°C at 1°C min−1 increments in continuous ramp mode. Data from the resulting melting curves were manually truncated to only include the range over which melting occurred for more accurate automatic determination of the melting temperature by the Thermofluor Acquire software.

GAP Assays

His-Gαi/q LONG R183C proteins were loaded with [32P]-γ-GTP and mixed with RGS proteins in assay buffer, and GTP hydrolysis was monitored as described (Chidiac and Ross, 1999). Data were plotted and statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0.4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alisa Glukhova for technical assistance with Thermofluor analysis, Michael Ragusa for his contribution to the generation of ΔNGαq baculovirus constructs, Aruna Ayer (née Shankaranarayanan) for the Gαi/q protein used in flow cytometry analysis, and Roger Sunahara and Phil Wedegaertner for WT and R183C Gαq plasmids, respectively, from which baculovirus constructs were generated. We thank Takeharu Kawano for providing the pFastBac plasmid encoding His6-Gαi/q LONG R183C. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL071818 and HL086865 (to J.T.) and GM061454 and GM074001 (to T.K.) and by National Science Foundation grants MCB0315888 and MCB0744739 (to R.S.M.). This research used the DNA Sequencing Core of the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center, which was supported by DK20572. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor for the support of this research program (Grant 085P1000817).

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The PDB accession numbers for crystal forms A and B reported in this paper are 4EKC and 4EKD, respectively.

Supplemental Information includes two 3D molecular models and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2012.12.016.

References

- Berman DM, Wilkie TM, Gilman AG. GAIP and RGS4 are GTPase-activating proteins for the Gi subfamily of G protein alpha subunits. Cell. 1996;86:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LS, Ramineni S, Hague C, Cladman W, Chidiac P, Levey AI, Hepler JR. RGS2 binds directly and selectively to the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor third intracellular loop to modulate Gq/11alpha signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21248–21256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer LL, Roman DL, Chung A, Larsen MJ, Greedy BM, Husbands SM, Neubig RR. Reversible, allosteric small-molecule inhibitors of regulator of G protein signaling proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:524–533. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Singer WD, Danesh SM, Sternweis PC, Sprang SR. Recognition of the activated states of Galpha13 by the rgRGS domain of PDZRhoGEF. Structure. 2008;16:1532–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidiac P, Ross EM. Phospholipase C-β1 directly accelerates GTP hydrolysis by Galphaq and acceleration is inhibited by Gbeta γ subunits. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19639–19643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidiac P, Markin VS, Ross EM. Kinetic control of guanine nucleotide binding to soluble Galpha(q) Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Kozasa T, Takekoshi K, De Gunzburg J, Kehrl JH. RGS14, a GTPase-activating protein for Gialpha, attenuates Gialpha- and G13alpha-mediated signaling pathways. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:569–576. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cladman W, Chidiac P. Characterization and comparison of RGS2 and RGS4 as GTPase-activating proteins for m2 muscarinic receptor-stimulated G(i) Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:654–659. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CW, Fariss RN, Sokal I, Palczewski K, Wensel TG. High expression levels in cones of RGS9, the predominant GTPase accelerating protein of rods. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5351–5356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PW, Tesmer JJ, Sterne-Marr R, Freeman LC, Benovic JL, Wedegaertner PB. Characterization of the GRK2 binding site of Galphaq. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53643–53652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401438200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBello PR, Garrison TR, Apanovitch DM, Hoffman G, Shuey DJ, Mason K, Cockett MI, Dohlman HG. Selective uncoupling of RGS action by a single point mutation in the G protein alpha-subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5780–5784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, He J, Ho WT, Ramineni S, Thal DM, Natesh R, Tesmer JJ, Hepler JR, Heximer SP. Unique hydrophobic extension of the RGS2 amphipathic helix domain imparts increased plasma membrane binding and function relative to other RGS R4/B subfamily members. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33064–33075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702685200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hague C, Bernstein LS, Ramineni S, Chen Z, Minneman KP, Hepler JR. Selective inhibition of alpha1A-adrenergic receptor signaling by RGS2 association with the receptor third intracellular loop. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27289–27295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Cowan CW, Wensel TG. RGS9, a GTPase accelerator for phototransduction. Neuron. 1998;20:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heximer SP, Watson N, Linder ME, Blumer KJ, Hepler JR. RGS2/G0S8 is a selective inhibitor of Gqalpha function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14389–14393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heximer SP, Srinivasa SP, Bernstein LS, Bernard JL, Linder ME, Hepler JR, Blumer KJ. G protein selectivity is a determinant of RGS2 function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34253–34259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heximer SP, Knutsen RH, Sun X, Kaltenbronn KM, Rhee MH, Peng N, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Penninger JM, Muslin AJ, Steinberg TH, et al. Hypertension and prolonged vasoconstrictor signaling in RGS2-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:445–452. doi: 10.1172/JCI15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Wensel TG. R9AP, a membrane anchor for the photoreceptor GTPase accelerating protein, RGS9-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9755–9760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152094799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Zhang Z, Wensel TG. Activation of RGS9-1GTPase acceleration by its membrane anchor, R9AP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14550–14554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingi T, Krumins AM, Chidiac P, Brothers GM, Chung S, Snow BE, Barnes CA, Lanahan AA, Siderovski DP, Ross EM, et al. Dynamic regulation of RGS2 suggests a novel mechanism in G-protein signaling and neuronal plasticity. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7178–7188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07178.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple AJ, Soundararajan M, Hutsell SQ, Roos AK, Urban DJ, Setola V, Temple BR, Roth BL, Knapp S, Willard FS, Siderovski DP. Structural determinants of G-protein alpha subunit selectivity by regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19402–19411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple AJ, Bosch DE, Giguère PM, Siderovski DP. Regulators of G-protein signaling and their Gα substrates: promises and challenges in their use as drug discovery targets. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:728–749. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan KL, Sarvazyan NA, Taussig R, Mackenzie RG, DiBello PR, Dohlman HG, Neubig RR. A point mutation in Galphao and Galphai1 blocks interaction with regulator of G protein signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12794–12797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodowski DT, Pitcher JA, Capel WD, Lefkowitz RJ, Tesmer JJ. Keeping G proteins at bay: a complex between G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and Gbetagamma. Science. 2003;300:1256–1262. doi: 10.1126/science.1082348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S, Shankaranarayanan A, Coco C, Ridilla M, Nance MR, Vettel C, Baltus D, Evelyn CR, Neubig RR, Wieland T, Tesmer JJ. Structure of Galphaq-p63RhoGEF-RhoA complex reveals a pathway for the activation of RhoA by GPCRs. Science. 2007;318:1923–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1147554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AM, Tesmer VM, Dhamsania VD, Thal DM, Gutierrez J, Chowdhury S, Suddala KC, Northup JK, Tesmer JJG. An autoinhibitory helix in the C-terminal region of phospholipase C-β mediates Gαq activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AM, Dutta S, Boguth CA, Skiniotis G, Tesmer JJG. Full-length Gαq-phospholipase C-β3 structure reveals interfaces of the C-terminal coiled-coil domain. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2497. Published online February 3, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martemyanov KA, Lishko PV, Calero N, Keresztes G, Sokolov M, Strissel KJ, Leskov IB, Hopp JA, Kolesnikov AV, Chen CK, et al. The DEP domain determines subcellular targeting of the GTPase activating protein RGS9 in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10175–10181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10175.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy FJ, Chanda PK, Cockett MI, Edris W, Jones PG, Mason K, Semus S, Powers R. NMR structure of free RGS4 reveals an induced conformational change upon binding Galpha. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7063–7073. doi: 10.1021/bi992760w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natochin M, Artemyev NO. A single mutation Asp229/Ser confers upon Gs alpha the ability to interact with regulators of G protein signaling. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13776–13780. doi: 10.1021/bi981155a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natochin M, McEntaffer RL, Artemyev NO. Mutational analysis of the Asn residue essential for RGS protein binding to G-proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6731–6735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner BA, Mukhopadhyay S, Tesmer JJ, Gilman AG, Ross EM. Modulation of the affinity and selectivity of RGS protein interaction with G α subunits by a conserved asparagine/serine residue. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7773–7779. doi: 10.1021/bi9906367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaranarayanan A, Thal DM, Tesmer VM, Roman DL, Neubig RR, Kozasa T, Tesmer JJ. Assembly of high order G alpha q-effector complexes with RGS proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34923–34934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805860200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren B, Blazer LL, Neubig RR. Regulators of G protein signaling proteins as targets for drug discovery. In: Lunn Charles A., editor. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, Vol 91: Membrane Proteins as Drug Targets. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2010. pp. 81–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiba NP, Yang CS, Huang T, Bae H, Hamm HE. The α-helical domain of Galphat determines specific interaction with regulator of G protein signaling 9. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8770–8778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep KC, Kercher MA, He W, Cowan CW, Wensel TG, Sigler PB. Structural determinants for regulation of phosphodiesterase by a G protein at 2. A Nature. 2001;409:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/35059138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep KC, Kercher MA, Wieland T, Chen CK, Simon MI, Sigler PB. Molecular architecture of Galphao and the structural basis for RGS16-mediated deactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6243–6248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801569105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan M, Willard FS, Kimple AJ, Turnbull AP, Ball LJ, Schoch GA, Gileadi C, Fedorov OY, Dowler EF, Higman VA, et al. Structural diversity in the RGS domain and its interaction with heterotrimeric G protein alpha-subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6457–6462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801508105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasa SP, Watson N, Overton MC, Blumer KJ. Mechanism of RGS4, a GTPase-activating protein for G protein alpha subunits. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1529–1533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer JJ. Structure and function of regulator of G protein signaling homology domains. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009;86:75–113. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(09)86004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer JJ, Berman DM, Gilman AG, Sprang SR. Structure of RGS4 bound to AlF4—activated G(i alpha1): stabilization of the transition state for GTP hydrolysis. Cell. 1997;89:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer VM, Kawano T, Shankaranarayanan A, Kozasa T, Tesmer JJ. Snapshot of activated G proteins at the membrane: the Galphaq-GRK2-Gbetagamma complex. Science. 2005;310:1686–1690. doi: 10.1126/science.1118890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang S, Woo AY, Zhu W, Xiao RP. Deregulation of RGS2 in cardiovascular diseases. Front Biosci (Schol Ed ) 2010;2:547–557. doi: 10.2741/s84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo GL, Ricks TK, Hicks SN, Cheever ML, Kawano T, Tsuboi K, Wang X, Montell C, Kozasa T, Sondek J, Harden TK. Kinetic scaffolding mediated by a phospholipase C-beta and Gq signaling complex. Science. 2010;330:974–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1193438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PT, Bourne HR. Fatty acylation of alpha z. Effects of palmitoylation and myristoylation on alpha z signaling. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9667–9675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie GX, Palmer PP. How regulators of G protein signaling achieve selective regulation. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.