Abstract

Brain extracellular matrix (ECM) is organized in specific patterns assumed to mirror local features of neuronal activity and synaptic plasticity. Aggrecan‐based perineuronal nets (PNs) and brevican‐based perisynaptic axonal coats (ACs) form major structural phenotypes of ECM contributing to the laminar characteristics of cortical areas. In Alzheimer's disease (AD), the deposition of amyloid proteins and processes related to neurofibrillary degeneration may affect the integrity of the ECM scaffold. In this study we investigate ECM organization in primary sensory, secondary and associative areas of the temporal and occipital lobe. By detecting all major PN components we show that the distribution, structure and molecular properties of PNs remain unchanged in AD. Intact PNs occurred in close proximity to amyloid plaques and were even located within their territory. Counting of PNs revealed no significant alteration in AD. Moreover, neurofibrillary tangles never occurred in neurons associated with PNs. ACs were only lost in the core of amyloid plaques in parallel with the loss of synaptic profiles. In contrast, hyaluronan was enriched in the majority of plaques. We conclude that the loss of brevican is associated with the loss of synapses, whereas PNs and related matrix components resist disintegration and may protect neurons from degeneration.

Keywords: aggrecan, astrocytes, β‐amyloid, brevican, chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan, microglia, neuroprotection, plaque

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular deposition of amyloid and intracellular neurofibrillary changes, formed by tau‐aggregation, are hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) 24, 49. In the cerebral cortex, amyloid deposits and tau aggregation show area‐specific distribution patterns leaving only a low portion of brain tissue unaffected in most advanced AD stages 9, 11, 15, 18.

It has been shown in animal models that brain matrix components can influence beta‐amyloid fibrillogenesis and may thus contribute to the progression of AD 8, 35. On the other hand, amyloid interacts with a variety of cofactors, including glycosaminoglycans and sulphated proteoglycans 4, 6, 25, 44. However, it has also been shown that the integrity of the pre‐existing extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold is severely damaged by amyloid deposition resulting in dramatic changes of the physicochemical properties, such as diffusion parameters of the extracellular micromilieu 2, 89. It is conceivable that amyloid formation is exclusively related to a displacement of the normal ECM. However, the molecular disintegration of the ECM may be a pivotal factor involved in the pathological cascade of AD. Mechanisms such as oxidative damage by free radicals 59, 64, 83 and enzymatic cleavage by matrix metalloproteinases (70)[reviewed in (84)] have been suggested.

The functional consequences of ECM displacement, disintegration and/or changed ratio of its components can be assumed to depend on the region‐ and cell‐specific organization of the ECM as demonstrated in various animal models 27, 28, 29, 30. Moreover, basic components such as chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans (CSPGs), hyaluronan and tenascins associated with perineuronal nets (PNs), perisynaptic axonal coats (ACs) and neuropil zones may be differently affected by pathological changes. The AD‐related molecular changes of the ECM have been described controversially. Hyaluronan associated with PNs was retained in Alzheimer cases (99). A widespread loss of PNs in the cerebral cortex was indicated after lectin staining using N‐acetylgalactosamine‐binding Vicia villosa and Wisteria floribunda agglutinin 10, 52, known to be markers of aggrecan‐based CSPG in PNs in many mammalian species 1, 39, 40, 66, 67. However, the region‐specific distribution pattern of PNs appeared to be unaffected if revealed by immunoreaction for core proteins of CSPGs (18). In a previous study, aggrecan‐based PNs have been shown to resist decomposition in subcortical regions severely affected by tau pathology (66). Together these studies lead to the apparent conundrum that loss of certain markers of PNs in AD has been reported 10, 52 but resistance and specific retention of other components was demonstrated 18, 66, 67. To complicate the matter further recent work has shown that the epitope likely detected by Wisteria floribunda agglutinin is found on aggrecan (36). Therefore this study was designed to resolve these apparently conflicting pieces of data and determine in a more precise manner how PNs and PN components are affected in AD.

In the present study, we investigate three neocortical areas that contribute to the processing of sensory information at different functional levels. All areas show a region‐specific organization of the ECM scaffold and AD pathology is known to express distinct laminar patterns sequentially evolving during progression of the disease 9, 11, 15, 57. We compare the primary visual cortex (area striata, Brodmann area 17) and a secondary visual area (area para‐striata, Brodmann area 18) in the occipital lobe with an area of the inferior temporal lobe involved in high‐level visual processing (Brodmann area 20). The study is focussed on the fate of major matrix components such as aggrecan, brevican, link protein, tenascin‐R and hyaluronan. To correlate our data with previously assumed loss of N‐acetylgalactosamine on CSPG side chains we particularly applied the WFA detection technique. We show that hyaluronan is highly enriched in amyloid plaques whereas aggrecan‐based N‐acetylgalactosamine‐containing PNs and brevican‐based ACs largely resist decomposition and are lost only after degeneration of neuronal structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cases

Brain material for this study was provided by Banner Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, AZ, USA.

Case recruitment and autopsy were performed in accordance with guidelines effective at Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program of Sun City, AZ (12). The definite diagnosis of AD for all cases used in this study was based on the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the hippocampal formation and neocortical areas and met the criteria of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry For AD (CERAD) (62). Staging of AD pathology was performed according to Braak and Braak (14).

For this study 12 AD cases and 12 age‐matched controls were used, six females and six males in each group (Table 1). The 24 brains used in this study were autopsied with a mean post‐mortem delay (PMD) of less than 3 hours thereby reducing potential postmortal changes of ECM components.

Table 1.

Profile of cases. Abbrevations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; PMD = post‐mortem delay; CERAD = Consortium to Establish a Registry For Alzheimer's Disease (0 none, A sparse, B moderate, C frequent); Co = control; COD = cause of death; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F = female; HlD = high likelihood of dementia; M = male; MMSE = mini‐mental state examination; NIA = National Institute on Aging.

| Case # | PMD (h) | Gender | Age (years) | Brain weight (g) | COD | Braak score | MMSE (last) | CERAD neuritic plaque score | CERAD criteria | NIA criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1 | 2.75 | F | 85 | 1020 | Pancreatic cancer | II | — | 0 | Not met | Not met |

| 2 | 1 | F | 85 | 1085 | Abdominal lymphoma | II | — | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 3 | 2.5 | F | 86 | 1145 | Pulmonary fibrosis | III | 27/30 | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 4 | 3 | F | 89 | 1200 | Congestive heart failure | III | 30/30 | A | Not met | Not met | |

| 5 | 2.75 | F | 75 | 1110 | Pulmonary embolus | III | 29/30 | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 6 | 2.5 | F | 87 | 1120 | Pneumonia/cancer | IV | 30/30 | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 7 | 2.5 | M | 74 | 1230 | Cardiac/respiratory failure | II | — | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 8 | 2.75 | M | 81 | 1290 | Cardiac/respiratory failure | I | — | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 9 | 1.66 | M | 78 | 1460 | Lung cancer/heart failure | I | 28/30 | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 10 | 3 | M | 82 | 1240 | Renal failure/COPD | III | 26/30 | A | Not met | Not met | |

| 11 | 4.75 | M | 86 | 1400 | Cardiac arrest | I | 28/30 | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| 12 | 5.5 | M | 89 | 1275 | COPD/respiratory distress | II | 30/30 | 0 | Not met | Not met | |

| Mean | 2.89 | 6/6 | 83.1 | 1214 | |||||||

| AD | 13 | 3 | F | 82 | 925 | Cardiac/respiratory failure | VI | — | C | Definite AD | HlD |

| 14 | 1.5 | F | 85 | 850 | Failure to thrive | VI | — | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 15 | 1.5 | F | 79 | 950 | Cardiac/respiratory failure end stage | VI | — | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 16 | 1.83 | F | 84 | 1080 | End‐stage AD | VI | 00/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 17 | 1.5 | F | 85 | 940 | Breast cancer; end‐stage AD | VI | 02/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 18 | 4 | F | 82 | 932 | Failure to thrive; end‐stage AD | VI | 24/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 19 | 2.33 | M | 77 | 1080 | End‐stage AD | VI | — | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 20 | 1.75 | M | 81 | 1150 | Pneumonia | VI | — | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 21 | 3.16 | M | 80 | 1000 | End‐stage AD | VI | 01/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 22 | 3.5 | M | 77 | 1200 | End‐stage AD | VI | 04/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 23 | 2.5 | M | 87 | 1100 | End‐stage AD | VI | 13/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| 24 | 2.25 | M | 78 | 1120 | End‐stage AD | VI | 07/30 | C | Definite AD | HlD | |

| Mean | 2.40 | 6/6 | 81.4 | 1027 |

Identification of anatomical regions and applied nomenclature

Anatomical regions were identified on Nissl‐stained and anti‐neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN) marked sections adopting the nomenclature of brain regions from brain atlases of human (58) and rhesus monkey (76).

Cytochemistry

Forty‐micrometer sections were treated with 2% H2O2 in 60% methanol for 60 minutes to abolish endogenous peroxidase activity followed by rinsing with phosphate‐buffered saline Tween (PBS‐T) (0.05% Tween). A subsequent blocking step with 2% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% casein and 0.5% donkey serum in PBS‐T was carried out for 30 minutes at room temperature to prevent non‐specific antibody binding. Sections were incubated over one or two nights with primary antibodies. Immunoreactivity was vizualized with biotinylated secondary antibodies (donkey anti‐mouse, donkey anti‐rabbit, donkey anti‐goat, donkey anti‐guinea pig; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and ExtrAvidin® peroxidase complex (Sigma, Munich, Germany) finished by diaminobenzidine (brown) or nickel‐enhanced diaminobenzidine (black) as chromogen. For double and triple fluorescent labellings immunoreactivity was vizualized with carbocyanine 2, 3 or 5 coupled secondary antibodies (Dianova).

Detection of ECM components

Antibodies against aggrecan core protein [Agg; 20, 66, 67, 93], brevican core protein, BEHAB/brevican 50 kD cleavage product [Brev; 36, 60], proteoglycan link protein 1 [HAPLN1; CRTL‐1; 21, 22, 36, 73] and tenascin‐R were used to detect ECM components in the human brain tissue (for detailed descriptions of antibodies see Table 2).

Table 2.

Cytochemical markers used for detection of extracellular matrix components, neurons, glial cells and Alzheimer's disease‐related pathology indicators.

| Detected components | Antibodies and binding proteins | Dilution | Source | Lot number | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix constituents | |||||

| N‐acetylgalactosamine | Biotinylated Wisteria floribunda agglutinin | 5 µg/mL | Sigma | # 26F‐8100 | Härtig et al (1992) (39) |

| N‐acetylgalactosamine | Biotinylated Vicia villosa agglutinin | 5 µg/mL | Vector Labs | # M0327 | Seeger et al (1996) (88) |

| Aggrecan, core protein | Mouse anti‐human aggrecan (HAG7D4) | 1:10 | Acris/Serotec | # 140510 | Brückner et al (2008) (20) |

| Brevican (50 kD fragment) | Rabbit anti‐human brevican (B50) | 1:2000 | R.T. Matthews | # b50 | Matthews et al (2000) (60) |

| Brevican core protein precursor | Rabbit anti‐human brevican | 1:200 | Sigma/Atlas | # R01205 | — |

| Link protein | Goat anti‐human CRTL‐1 (HAPLN1) | 1:400 | R&D Systems | # VBN 0107081 | Carulli et al (2007) (21) |

| Hyaluronan | Biotinylated hyaluronic acid‐binding protein | 10 µg/mL | Cape Cod | # D 00100295 | Carulli et al (2007) (21) |

| Tenascin‐R | Mouse anti‐bovine tenascin‐R (619) | 1:50 | R&D Systems | # IZG02 | Brückner et al (2003) (19) |

| Cellular markers | |||||

| Neuron‐specific nuclear protein | Mouse anti‐NeuN MAB 377 clone A60 | 1:100 | Millipore | # 0507004415 | Poirier et al (2010) (79) |

| Parvalbumin | Rabbit anti‐rat PV28 | 1:1000 | Swant | # 5.5 | Celio and Heizmann (1981) (23) |

| Synaptic markers | |||||

| Synaptophysin | Mouse anti‐synaptophysin clone SY38 | 1:100 | Dako | # 00027760 | Diepholder et al (1991) (26) |

| Synaptobrevin | Mouse anti‐synaptobrevin 2 (VAMP 2) | 1:250 | Synaptic Systems | # 104211/14 | Washbourne et al (1995) (94) |

| Glia markers | |||||

| Ionized calcium binding adaptor1 | Rabbit anti‐Iba1 | 1:500 | Wako | # CDQ5232 | Kanazawa et al (2002) (51) |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) | Rabbit anti‐GFAP | 1:1000 | Dako | # Z033401096302 | Morawski et al (2010) (69) |

| Glial glutamate transporter‐1 | Guinea pig anti‐GLT‐1 | 1:1000 | Millipore | # 848009 | Lauderback et al (2001) (55) |

| Pathology markers | |||||

| Phosphorylated tau | Rabbit anti‐human tau pT205 | 1:500 | Invitrogen | # 5193173 | Alonso et al (2001) (5) |

| Phosphorylated tau | Mouse anti‐human tau AT8 | 1:500 | Thermo Scientific | # JG112461 | Goedert et al (1994) (38); Goedert (1996) (37) |

| Pyroglutamate‐modified Abeta | Mouse anti‐pE‐Aβ | 1:200 | Synaptic Systems | # 218011/4 | Schilling et al (2008) (87) |

| Pyroglutamate‐modified Abeta | Rabbit anti‐pE‐Aβ | 1:200 | Synaptic Systems | # 218003/4 | Schilling et al (2008) (87) |

| Abeta | Biotinylated 4G8 | 1:2000 | Covance (SIGNET) | # 2LC01595 | Frautschy et al (1998) (33) |

Additionally, biotinylated lectins, Wisteria floribunda lectin [WFA; 16, 21, 39, 69] and Vicia villosa lectin [VVA; 52, 71, 88], which are known to detect N‐acetylgalactosamine in matrix constituents of PNs were used. To test the specificity of the WFA binding, free‐floating sections were pretreated with the blocking sugar melbiose at 200 mM for 1 h. Pretreated sections showed no specific staining. Further, a digestion with chondroitinase ABC (Chase) from Proteus vulgaris (0.5 U/mL, Sigma‐Aldrich, C2905) erased all specific binding of the lectin (data not shown) as previously demonstrated 17, 54.

Furthermore, the biotinylated hyaluronan‐binding protein (B‐HABP) was used to detect hyaluronan 17, 21, 69. To test the specificity of the B‐HABP binding, free‐floating sections were pretreated with hyaluronidase (Hyase) from Streptomyces hyalurolyticus (50 U/mL 0.1 M PBS, pH 5.0; Sigma, H1136) (54) for 4 h, 8 h and 12 h at 37°C. Binding of B‐HABP was at the background level after enzymatic treatment of sections (for detailed description of lectins and binding protein see Table 2).

Detection of neuronal populations

To detect neurons and specific neuronal subpopulations the anti‐NeuN antibody and the anti‐parvalbumin (Parv; PV28) antibody were used [23, 39, 40; for detailed description of neuronal markers see Table 2].

Detection of synapses

Investigations on potential alterations of synapses were made using antibodies to synaptophysin (96) and synaptobrevin (VAMP2; (94); for detailed description of synaptic markers see Table 2).

Detection of glia cells and macrophages

To investigate glia cells and macrophages potentially present in the human brain we used antibodies to Iba1 (microglia), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (astrocytes) and GLT‐1 [glial glutamate transporter (EAAT2); astrocytes, especially fine processes usually not detected by GFAP antibodies; (55)]. Pre‐absorption of the antiserum with the immunogen peptide (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; AG391) completely abolishes the immunostaining (for detailed description of glial markers see Table 2).

Detection of tau and amyloid pathology

Cytoskeletal pathology related to hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of the tau protein sections was detected by a variety of well‐characterized antibodies; for this purpose we used anti‐tau phosphospecific antibody [pT205; (5)] and anti‐PHF‐tau antibody [clone AT8; 37, 38, 80]. For the detection of amyloid deposits (plaques) anti‐pyroglu Abeta IgG antibodies 43, 68 and 4G8 antibody were used. The 4G8 antibody is reactive to amino acid residues 17–25 of beta amyloid and reacts as well with APP isoforms (for detailed description of pathology markers see Table 2).

Controls

In control experiments, primary antibodies were omitted, yielding the unstained sections.

Microscopy

Light microscopy, confocal laser scanning microscopy and image processing

Tissue sections were examined with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope equipped with a motorised stage (Märzhäuser, Wetzlar, Germany) with MosaiX software and by means of a CCD camera (Zeiss MRC) connected to an Axiovision 4.6 image analysis system (Zeiss, Germany) for light microscopy. Fluorescence labelling was examined with a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss, Jena, Germany). For secondary Cy2‐labelled slices (green fluorescence), an argon laser with 488 nm excitation was used and emission from Cy2 was recorded at 510 nm applying a low‐range band pass (505–550 nm). For secondary Cy3‐labelled slices (red fluorescence), a helium‐neon laser with 543 nm excitation was applied and emission from Cy3 at 570 nm was detected applying high‐range band pass (560–615 nm). For secondary Cy5‐labelled slices (infrared fluorescence) a helium‐neon laser with 633 nm excitation was applied and emission from Cy5 at 650 nm was detected applying long pass (650 nm) filter. Photoshop CS2 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used to process the images with minimal alterations to the brightness, sharpness, color saturation and contrast. For sake of uniform presentation some fluorescence images were adapted to pseudocolors.

Stereological analysis

For stereological analysis, the optical fractionator method 61, 95 was used to estimate numerical densities of PN‐ensheathed neurons (Bio‐WFA) and NeuN‐stained neurons in selected areas of neocortex. PNs that surrounded non‐pyramidal cells and PNs around pyramidal neurons were counted (Table 3). In order to perform stereological analyses in a restricted domain of neocortex it is first necessary to establish the anatomical boundaries of the considered region with as much precision as possible to ensure accuracy and reliability of the stereologic sampling and validity of the estimates. In present investigation the number of PNs and neurons was counted in discrete neocortical areas of occipital cortex (area 17 and 18) of five control brains and five cases with a neuropathologically confirmed diagnosis of AD and temporal cortex (area 20) of five control brains and five cases with AD. Counts were performed on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus microscope equipped with a motorized stage, a Ludl MAC 5000 (LEP, Hawthorne, NY, USA) and a digital camera 9000 (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT, USA). Stereo Investigator software 6 (MicroBrightField) was used to analyze frontal sections (nominal thickness of 40 µm) of selected areas. Each section was first viewed at low magnification (5×) for outlining the relevant parts of cortical areas, and disector frames were placed in a systematic‐consecutive fashion in the delineated regions of the sections. Neurons that fell within these disector frames (150 × 150 µm) were then counted at high magnification (20×). On average the post‐processing shrinkage of the tissues resulted in a final section thickness of 16 ± 2 µm, which permitted a consistent sampling of 10 µm with the disector and the use of guard zones of 2 µm on either sides of the section. Three sections per case and area investigated were used. The number of PNs and NeuN‐stained neurons were converted to numerical density per mm2. In all cases, the experimenter was blinded to the experimental conditions.

Table 3.

Stereological counts of Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA)‐reactive perineuronal nets (PNs) related to the number of NeuN‐stained neurons in area 17 and 18 of occipital isocortex and area 20 of temporal isocortex in control brains and brains affected by Alzheimer's disease (AD).

| Area | PNs (mm2) ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Controls | n = 5 | |

| 17 | 65 ± 3 | |

| 18 | 66 ± 7 | |

| 20 | 17 ± 7 | |

| AD | n = 5 | |

| 17 | 68 ± 5 | |

| 18 | 67 ± 8 | |

| 20 | 19 ± 3 |

No significant difference could be detected in the number of WFA‐positive PNs.

A17 P = 0.2; A18 P = 0.8; A20 P = 0.4.

Statistical analysis

All counted sections were analyzed using an unpaired t‐test for each group (AD and non‐demented control), comparing AD‐affected brains with the respective region of non‐demented control brains.

RESULTS

The investigated visual cortical areas A 17, A 18 and A 20 show an area‐specific matrix organization. This confirms and extends existing studies focused on the primary and secondary visual cortex 47, 88. All components detected in the present study, N‐acetylgalactosamine, aggrecan, brevican, link protein, tenascin‐R and hyaluronan, contribute to the area‐specific matrix pattern. The two major structural features of matrix phenotypes, PNs and synapse‐associated ACs, could be detected. In the visual cortical areas studied PNs contain all matrix components, whereas ACs could only be detected by brevican and link protein 1‐immunoreaction. The most conspicuous pattern of PN staining originates from the established markers WFA detecting N‐acetylgalactosamine and aggrecan core‐protein antibody, whereas brevican‐immunoreaction revealed a unique selectivity of AC staining.

Area‐specific laminar distribution patterns of PNs and perisynaptic ACs of ECM in the control brain

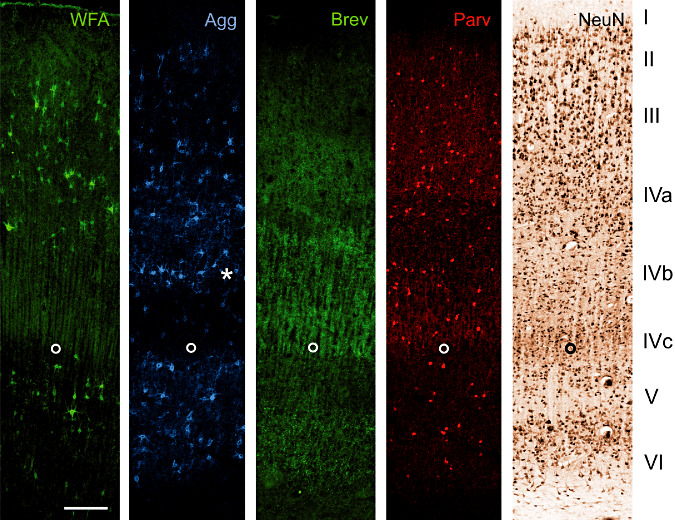

We used two neuronal markers (NeuN and Parv) to demonstrate the basic laminar profile (1, 2, 3).

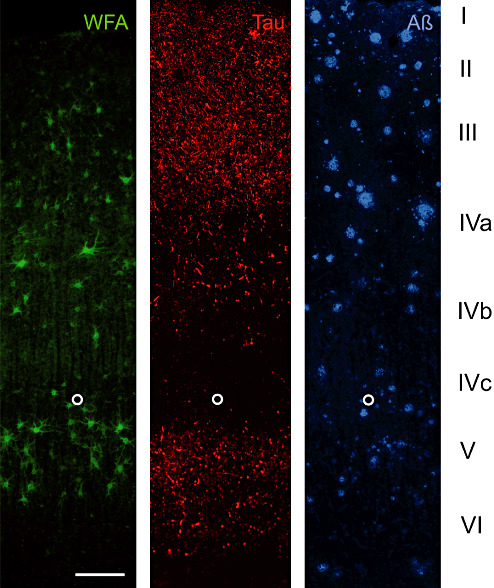

Figure 1.

A17 Co: Laminar distribution of major extracellular matrix components in area 17 of human control brain. Two neuronal markers [neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN) and parvalbumin (Parv)] are shown to indicate the basic laminar profile. Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) as established marker for perineuronal nets indicates many nets in layer III, IVa and V. Only few perineuronal nets can be seen in layer VI whereas layer I, II and IVc are virtually devoid of WFA‐stained nets. Compared with WFA staining, pan‐aggrecan antibody HAG (Agg) reveals more perineuronal nets, indicating variations in aggrecan glycosylation. This becomes clear especially in layer IVb (asterisk) containing many Agg positive nets but devoid of WFA‐stained perineuronal nets. Brevican antibody B50 (Brev) reveals a clearly different laminar pattern. Immunoreactivity is mainly restricted to layers IVa, IVc and VI. Further, brevican antibody B50 (Brev) does not show the typical perineuronal net‐like appearance but reveals dot‐like structures. The open circle marks the lower edge of layer IVc. Scale bar = 200 µm.

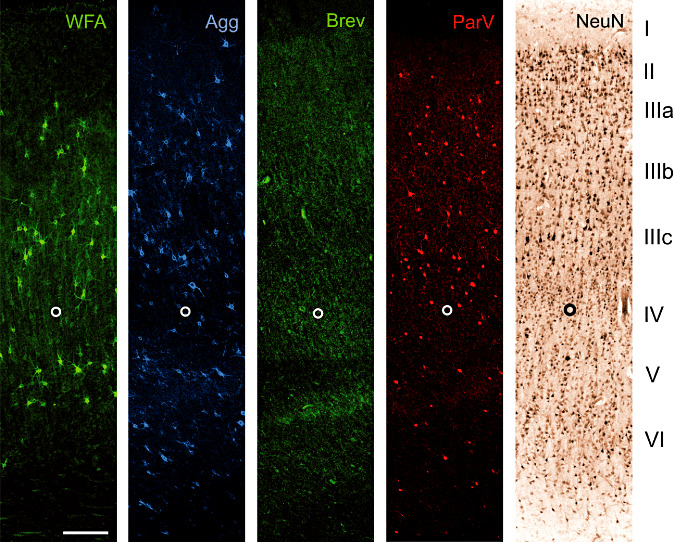

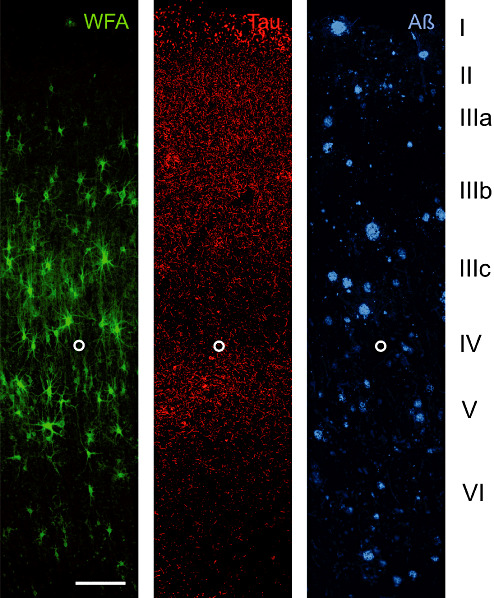

Figure 2.

A18 Co: Laminar distribution of major extracellular matrix components in area 18 of human control brain. Two neuronal markers [neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN) and parvalbumin (Parv)] are shown to indicate the basic laminar profile. Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) indicates many perineuronal nets in layer III and V. Low numbers of perineuronal nets can be seen in layer VI whereas layer I, II and IV are virtually devoid of WFA‐stained nets. Compared with WFA staining, pan‐aggrecan antibody HAG (Agg) detects more perineuronal nets, indicating heterogeneity in aggrecan glycosylation. This becomes evident in layer II and VI containing Agg positive nets but devoid of WFA‐stained perineuronal nets. Brevican antibody B50 (Brev) reveals dot‐like matrix structures in a clearly different laminar pattern. Immunoreactivity is mainly restricted to layers IIIb, IV, lower V. The open circle marks the lower edge of layer IV. Scale bar = 200 µm.

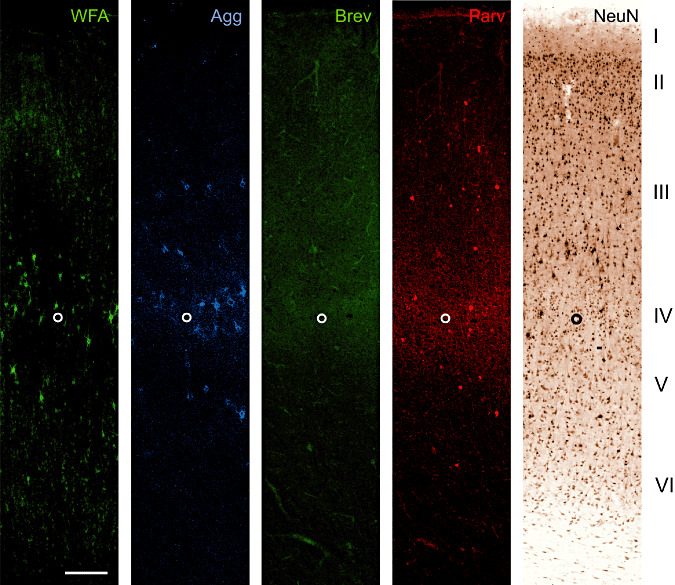

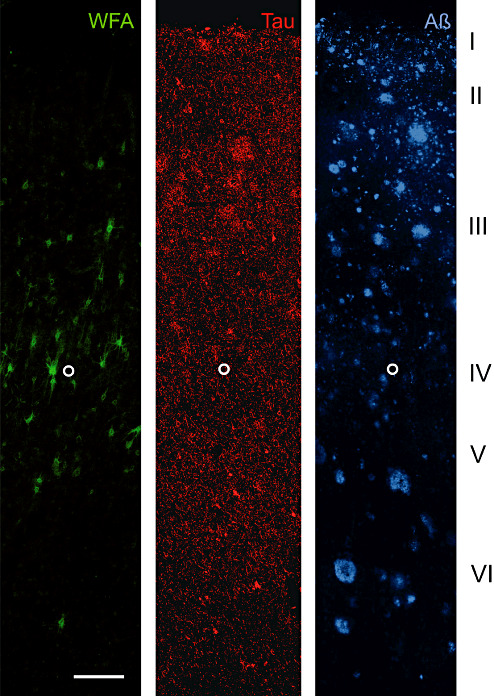

Figure 3.

A20 Co: Laminar distribution of major extracellular matrix components in area 20 of human control brain. Two neuronal markers [neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN) and parvalbumin (Parv)] are shown to indicate the basic laminar profile. Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) indicates an identifiable proportion of perineuronal nets in layer III and IV. Perineuronal nets only sporadically occur in layer V and VI whereas layer I and II are virtually devoid of WFA‐stained nets. Compared with WFA staining, pan‐aggrecan antibody HAG (Agg) reveals only slightly more perineuronal nets. The number of perineuronal nets in area 20 is considerably low compared with areas 17 and 18. Brevican B50 (Brev) immunoreactivity is virtually absent in all layers. The open circle marks the lower edge of layer IV. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Area 17

WFA labels many PNs in layer III, IVa and V. Additionally, low numbers of PNs can be seen in layer VI whereas layer I, II and IVc are virtually devoid of WFA‐stained PNs. Compared with WFA staining, aggrecan immunoreaction reveals higher numbers of PNs, indicating variations in aggrecan glycosylation. This becomes clear especially in layer IVb containing many Agg‐positive nets but devoid of WFA‐stained PNs. In contrast to aggrecan stained PNs, brevican antibody B50 clearly reveals staining mainly restricted to layers IVa, IVc and VI. It is a remarkable finding that brevican antibody B50 does not show the typical PN‐like appearance but reveals dot‐like structures known to be perisynaptic ACs.

Area 18

WFA labels many PNs in layer III and V. Low numbers of PNs can be seen in layer VI whereas layer I, II and IV are spared from WFA‐stained PNs. The heterogeneity in aggrecan glycosylation again is indicated by Agg‐positive PNs in layer II and VI devoid of WFA‐stained PNs. Brevican positive ACs are mainly restricted to layers IIIb, IV, lower V.

Area 20

The number of PNs in area 20 is considerably low compared with areas 17 and 18. WFA reveals a small number of PNs in layer III and IV. PNs are only sporadically present in layer V and VI whereas layers I and II are virtually devoid of WFA‐stained nets. Compared with WFA staining, aggrecan‐immunoreaction reveals only slightly more PNs.

Brevican positive ACs are virtually absent in all layers.

In Table 4 semi‐quantitative densities of PNs and ACs are given summarizing the results of the area‐specific laminar distribution patterns of ECM in the control and AD‐affected brains (Table 4).

Table 4.

Semi‐quantitative densities of PNs and ACs summarizing the results of the area‐specific laminar distribution patterns of extracellular matrix in the investigated brains. Abbreviations: − = none; + = low; ++ = moderate; +++ = high.

| Area | PNs | ACs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WFA | Agg | Brev | |

| Area 17 | |||

| Layer I | − | − | − |

| Layer II | − | + | − |

| Layer III | +++ | +++ | − |

| Layer IVa | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Layer IVb | − | +++ | + |

| Layer IVc | − | + | +++ |

| Layer V | +++ | +++ | + |

| Layer VI | + | ++ | ++ |

| Area 18 | |||

| Layer I | − | − | − |

| Layer II | − | + | + |

| Layer IIIa | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Layer IIIb | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Layer IIIc | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Layer IV | + | ++ | +++ |

| Layer V | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Layer VI | + | ++ | ++ |

| Area 20 | |||

| Layer I | − | − | − |

| Layer II | − | − | − |

| Layer III | + | + | − |

| Layer IV | ++ | ++ | − |

| Layer V | + | + | − |

| Layer VI | + | + | − |

ECM and tau‐pathology

PNs

The brain material used in our study originated from patients at advanced stage of AD (Table 1) showing extensive amyloid and tau pathology even in the visual cortex. The matrix laminar pattern described for control brains is not changed in brains severely affected by AD. Laminar pattern of tau pathology and WFA stained PNs tend to be inverse.

As shown for control brain in area 17, WFA indicates PNs in layers III, IVa and V. Tau pathology to some extent overlaps with these PN‐rich layers. In Area 18, WFA staining shows PNs in layers III and V. Tau pathology in contrast seems to be less severe in PN‐rich layer III. In Area 20, WFA staining reveals an identifiable proportion of PNs in layers III and IV. PNs even persist in layers with severe tau pathology. Quantification revealed no significant change in the number of WFA‐stained PNs (Table 3).

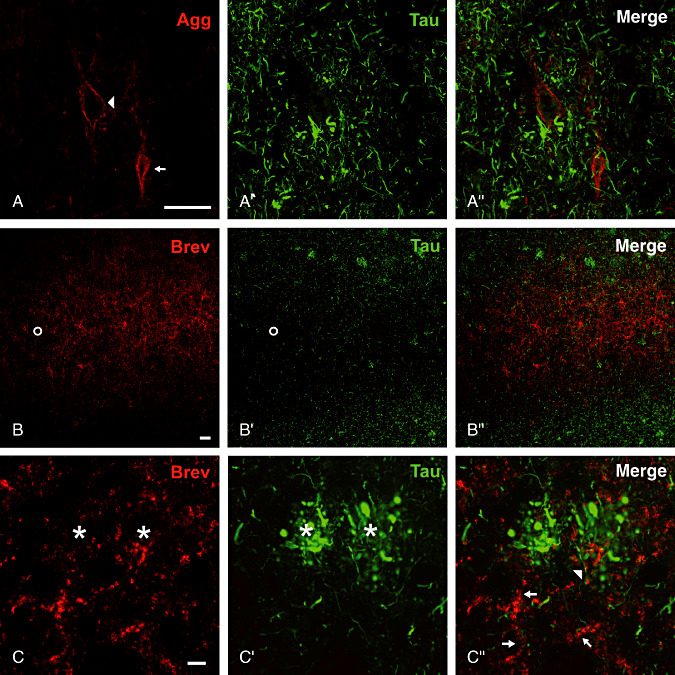

Interneurons as well as pyramidal cells ensheathed by a PN are devoid of cytoskeletal changes such as tau‐immunoreactive tangles (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Neurons with aggrecan‐immunoreactive perineuronal nets and neurites associated with brevican (Brev) immunoreactive axonal coats are devoid of cytoskeletal changes indicated by tau‐immunoreaction. A–A″. Perineuronal nets persisting in the close vicinity to neuritic plaques. Pyramidal cell (arrowhead) and interneuron (arrow) associated with perineuronal nets are devoid of neurofibrillary tangles. B–B″. Complementary laminar distribution of brevican (Brev) immunoreactive axonal coats and tau pathology. The lower layer V (open circle) as an AC‐rich zone is largely spared from formation of tangles and neuropil threads in area 18. D–D″. Tau‐positive neurites are rarely seen in the close proximity to brevican‐immunoreactive structures (arrow head). The majority of axonal coats enwrap neuronal processes negative for tau‐immunoreaction (arrows) and is largely retained in the territories of neuritic plaques (asterisks). Scale bar in A–A″ and B–B″ = 50 µm, in C–C″ = 10 µm.

Perisynaptic ACs

The clear laminar distribution of brevican‐immunoreactive ACs (1, 2, 3), different from laminar pattern of aggrecan‐stained PNs, is not changed in brains severely affected by AD. However, AC laminar distribution to some extent displays an inverse pattern to tau pathology. An example is given in Figure 5 displaying the lower layer V as an AC‐rich zone largely spared from tau pathology in area 18.

Figure 5.

A17 AD: Laminar distribution of perineuronal nets (PNs) detected by Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) in area 17 of Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain. Two key pathology markers, hyperphosphorylated tau (Tau) and amyloid beta (Aβ) are shown to demonstrate the basic laminar pathology profile. WFA labels N‐acetylgalactosamine containing PNs in layer III, IVa and V. Only few PNs can be seen in layer VI whereas layer I, II and IVc are virtually devoid of WFA‐stained nets. This laminar distribution resembles the distribution pattern in control brain. Tau pathology to some extent overlaps with PN‐rich layers but PN‐ensheathed neurons invariably are devoid of tau pathology, whereas no obvious relation of amyloid plaque distribution and presence of PNs is detectable. The open circle marks the lower edge of layer IVc. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Unchanged and reduced matrix components related to amyloid pathology

The well‐known neuronal, astrocytic and microglial alterations related to extracellular amyloid deposition may result in dramatic changes in ECM organization (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Despite the noticeable laminar deposition of amyloid plaques, no obvious relation in the distribution of plaques and PNs is detectable (5, 6, 7).

Figure 6.

A18 AD: Laminar distribution of perineuronal nets (PNs) detected by Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) in area 18 of human Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain. Two key pathology markers, hyperphosphorylated tau (Tau) and amyloid beta (Aβ) are shown to demonstrate the basic laminar pathology profile. Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) indicates N‐acetylgalactosamine‐containing PNs in layer III and V. Low numbers of PNs can be seen in layer VI. This laminar distribution resembles the distribution pattern in control brain. Tau pathology to some extent overlaps with PN‐rich layers but PN‐ensheathed neurons invariably are devoid of tau pathology, whereas no obvious relation of amyloid plaque distribution and presence of PNs is detectable. The open circle marks the lower edge of layer IV. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Figure 7.

A20 AD: Laminar distribution of perineuronal nets (PNs) detected by Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA) in area 20 of human Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain. Two key pathology markers AT8 (hyperphosphorylated Tau) and amyloid beta (Aβ)] are shown to demonstrate the basic laminar pathology profile. WFA labels an identifiable proportion of N‐acetylgalactosamine‐containing PNs in layer III and IV. Only sporadic occurrence of PNs can be seen in layer V and VI. This laminar distribution resembles the distribution pattern in control brain. PNs even persist in layers with severe tau pathology and PN‐ensheathed neurons invariably are devoid of tau pathology. No obvious relation of amyloid plaque distribution and PN appearance is detectable. The open circle marks the lower edge of layer IV. Scale bar = 200 µm.

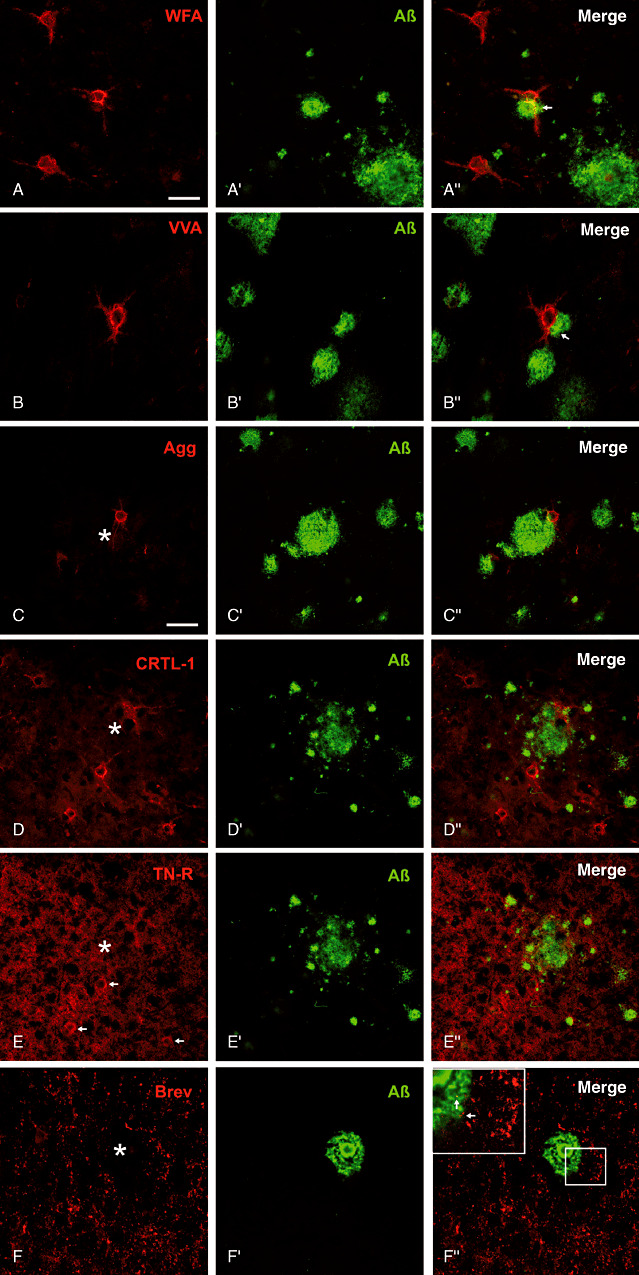

PNs

PNs detected by N‐acetylgalactosamine (WFA and VVA), aggrecan, link protein and tenascin‐R can be seen even in the close vicinity of amyloid depositions (Figure 8). Sometimes neuronal dendritic domains associated with PNs even penetrate the coronal zone of amyloid plaques. We could not detect PNs in the core of amyloid plaques.

Figure 8.

Major extracellular matrix components in spatial relation to amyloid plaque pathology. (A,B) Well‐preserved N‐acetylgalactosamin reactive perineuronal nets (PNs) are located even at the outer zone of the amyloid plaque corona. Occasionally PN‐ensheathed dendrites are penetrating the amyloid deposits (arrows). C. Aggrecan (Agg) core protein immunoreactive nets and D. PNs immunoreactive for link protein 1 occur in close contact to the amyloid plaque territory. E. Tenascin‐R (TN‐R) displays an ubiquitous neuropil immunoreaction and some PNs (arrows) can be detected without obvious alteration in the close proximity of multiple plaques. F. Brevican (Brev) immunoreactive perisynaptic axonal coats of extracellular matrix are clearly stained without evident alterations in the surrounding plaque territory. (Insert in F) Additionally, some axonal coats are even detectable within the plaque corona (arrows) whereas the plaque core is devoid of brevican immunoreactivity. Scale bar in A = 50 µm applies for all pictures.

Perisynaptic ACs

Perisynaptic ACs immunoreactive for brevican are clearly stained without evident alterations in the surrounding plaque territory (Figure 8F–F″″). Additionally, some ACs are even detectable within the plaque corona, whereas the plaque core is devoid of brevican immunoreactivity (Figure 8F′″ insert).

Enriched hyaluronan related to amyloid pathology

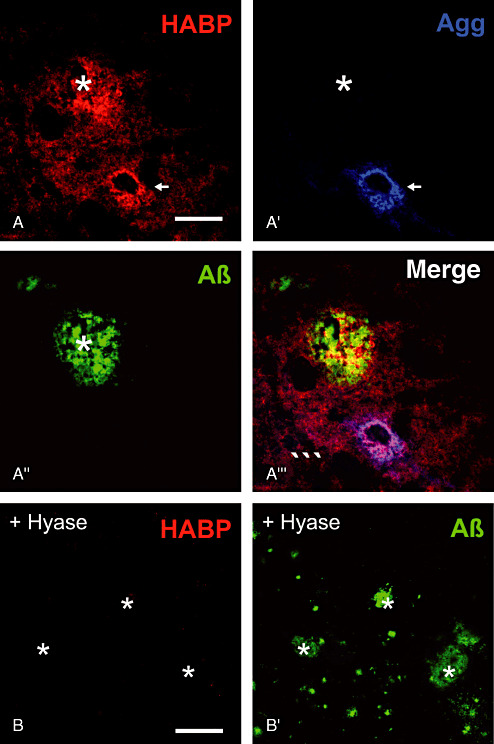

Regarding all ECM components investigated in this study hyaluronan is the only constituent obviously enriched in amyloid plaque territories. Hyaluronan persists in the surrounding plaque territories in concentrations corresponding to the neuropil of control brains (Figure 9A–A′″). However, the marginal and coronal zones of plaques reveal a clearly higher concentration of hyaluronan indicated by intensive HABP staining. The stained hyaluronan and amyloid depositions only partly overlap but show a largely interdigitated appearance. The central core region is typically spared from hyaluronan staining. Treatment of sections with Hyase resulted in absence of hyaluronan (Figure 9B–B′).

Figure 9.

Hyaluronan as ubiquitous component of extracellular matrix detected by hyaluronic acid‐binding protein (HABP). A. Hyaluronan is enriched in amyloid plaques (asterisk) and persists in PNs (arrows). A′. In contrast to hyaluronan aggrecan remains unaltered. (A″,B′) Aβ‐immunoreaction is used to display the location of plaques. A′′′. Amyloid deposits only partially overlap with plaque territories characterized by elevated HABP staining. (B,B′) Treatment of sections with hyaluronidase (Hyase) resulted in absence of hyaluronan staining. Scale bar in A–A′′′ = 50 µm, in B–B′ = 100 µm.

Effects of prolonged PMD on WFA and aggrecan reactivity

To assess the potential effects of prolonged PMD, as often taking place in human brain samples, on WFA and aggrecan reactivity we performed experiments potentially mimicking those conditions. We used four adult C57/Bl6 mice applying the following post‐mortem experimental procedure: The first mouse was sacrificed and perfused immediately with standard fixation protocol (0 h PMD), the second mouse was sacrificed and exposed to 37°C for 3 h (3 h PMD) and immersion fixed, the third mouse was exposed to 4°C for 24 h (24 h PMD cold conditions) and immersion fixed. Finally, the fourth mouse was exposed to 37°C for 24 h (24 h PMD warm conditions) and immersion fixed. The incidental effects on the ECM were investigated using biotinylated WFA lectin as well as aggrecan antibody on somatosensory cortex (Supporting Information Figure S1). An obvious decline in WFA reactivity can be detected with increasing PMD, whereas aggrecan reactivity seems largely be unaffected even under prolonged PMD (warm condition) (Supporting Information Figure S2).

DISCUSSION

Technical considerations

Previously, a loss of PNs in AD was reported by two groups, based on observations using detection of N‐acetylgalactosamine by lectins WFA (10) and VVA (52). In our previous studies, we also failed to obtain a staining with WFA and VVA in the vast majority of our standard clinical autopsy cases irrespectively whether AD or control brains 18, 66. However, the immunohistochemical detection of the CSPG core protein revealed the presence of PNs and ACs. This may suggest that the N‐acetylgalactosamine‐containing chondroitin side chains of CSPGs are highly sensitive to decomposition. Such sensitivity of WFA‐binding sites was already demonstrated after experimental stroke in the rat cerebral cortex (45). In the present study using well‐preserved brain tissue treated according to the “Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program”(12) the lectin‐binding (WFA and VVA) capacity was retained in all control and AD cases. It appears that the loss of lectin binding sites is caused by post‐mortem changes. This has been documented and discussed for an appreciable number of proteins such as Parv 7, 32, 48, 56[reviewed in (12)]. Post‐mortem reductions occur within the first 4–8 h (12). In addition, initial tissue processing, fixation and long‐time storage of tissue blocks and sections may be considered as factors affecting the preservation of matrix constituents. Also, one has to consider that there might be a substantial loss of cells and tissue volume because of pre‐mortem changes in AD. This loss could potentially lead to bias in PN per neuron or area when a significant number of PN‐ensheathed neurons would be lost or a significant reduction of tissue volume might take place during progression of AD. However, as the mean densities of PNs were slightly increasing in the AD cases this points even more to a lack of alterations of PNs in AD. Systematic studies on the importance of these different factors on ECM integrity in the human brain have not been performed. The fact that brains of laboratory animals, immediately perfusion‐fixed after death, consistently show well‐preserved ECM scaffold additionally points to the importance of these technical conditions (Supporting Information Figure S2). The experiments performed to assess effects of prolonged PMD on WFA and aggrecan reactivity clearly showed a substantial effect on the N‐acetylgalactosamine (WFA) reactivity under prolonged PMD conditions, whereas aggrecan reactivity virtually seems to be unaffected (Supporting Information Figure S2). This strongly supports our hypothesis that the loss of lectin (WFA) N‐acetylgalactosamine binding sites is a consequence of post‐mortem changes taking place in the first few hours after death.

Area‐specific laminar distribution patterns of PNs and perisynaptic ACs of ECM

A major result of the present study is that the laminar patterns of the various ECM components were not altered in the investigated AD brain regions. The area‐specific characteristics in the primary, secondary and associative visual cortex were completely retained. Despite advanced stages of amyloid and tau pathology, PNs and ACs, two widely distributed structural phenotypes of condensed ECM were virtually unchanged. This is in agreement with our previous work in human APP transgenic Tg2576 mice showing advanced cortical amyloid plaque pathology (69) and with biochemical data (50).

ECM and tau pathology

Our study confirms and extends the results of previous investigations showing the absence of neurofibrillary tangles in neurons ensheathed by aggrecan‐based PNs in cortical and subcortical regions 18, 42, 66. Additionally, neurites associated with brevican‐based ACs were not correlated with tau pathology.

ECM and amyloid pathology

The defined zonal organization of dense core amyloid plaques related to alterations of neuronal and glial structures may be correlated with changes in the composition of ECM scaffold. The plaque core as a territory of complete loss of cellular structures is also characterized by a loss of all investigated matrix constituents. In the more peripheral plaque zones such as corona and marginal zone no alteration of N‐acetylgalactosamine, aggrecan, brevican, link protein and tenascin‐R could be detected. These zones are characterized by fibrillar amyloid deposits, damage and loss of neurons and synapses, as well as the occurrence of numerous dystrophic neurites in the close proximity to reactive microglia and astrocytic processes 3, 31, 92, 97. It is conceivable that glial cells capable of proteolytic degrading amyloid β‐protein 81, 98, 100 release proteases that cleave ECM proteoglycans around intact neurons, thereby initiating neuronal damage. Metalloproteinases, and especially enzymes with aggrecan and brevican‐cleaving substrate specificity, such as ADAMTS4 and 5 70, 72, 85, 91 and MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 13, 100 may substantially affect PNs and ACs.

It remains to be elucidated if the persistence of all the investigated ECM proteins is accomplished by TIMPs or other MMP‐inhibiting factors, or if it is caused by a compensatory upregulation of matrix proteins.

Hyaluronan, typically complexed with proteoglycans and link protein, was also found to be unchanged in cortical PNs as previously shown in basal forebrain regions (99). However, in contrast to persisting levels of ECM proteins and hyaluronan in PNs, hyaluronan is enriched in the coronal and marginal zones of the amyloid plaques. This is in concordance with biochemical investigations showing an increase of hyaluronan up to 26% in the temporal lobe of AD patients (50). The focal elevation of hyaluronan concentration may be related to reactive astrocytes in the surrounding tissue, as the hyaluronan receptor CD44 is located at radially oriented astrocytic processes massively penetrating these plaque territories (3).

Functional implications

The preservation of PNs and ACs in AD brains suggest that the functions attributed to these structures are largely retained. In addition to potential functions related to regulation of the ionic micromilieu 16, 41, 65 and synaptic plasticity 27, 28, 29, 30, 46, 78, 82 ECM components are likely involved in neuroprotective actions 18, 64, 65, 66, 69. Reduced vulnerability of PN‐ensheathed neurons against iron‐induced oxidative processes occurred in human cerebral cortex 64, 65. Protection of neurons by PNs against amyloid toxicity (63), damage by excitatory amino acids (74) and oxygen or glucose deprivation (59) was shown in in vitro models.

The upregulation of hyaluronan in territories of amyloid plaques may also have functional consequences. As hyaluronan is critically involved in the regulation of synaptic plasticity 34, 53 changes of hyaluronan levels may distinctly affect the synaptic refinement within plaque territories that may counteract the loss of synapses characterising AD 77, 86, 90.

Additionally, growth and mobility of glial structures may also be influenced (75).

CONCLUSION

The unchanged appearance of the ECM proteins associated with PNs and ACs in AD suggests maintenance of their physiological functions. These functions may include a protective role preventing neuronal death.

The enrichment of hyaluronan in amyloid plaques may substantially influence the reorganization of neuronal structures and the penetration of glial cell processes into the inner plaque territories.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Profound neuronal (A–C) and glial (D,E) alterations related to amyloid plaque pathology in the visual cortex of AD patients indicating the advanced stage of disease. The organization of amyloid plaque is shown in A, D, E and F indicating the core (asterisks), the corona (filled circle) and the marginal plaque zone (filled triangle). A. Synaptobrevin immunoreaction indicates dystrophic neurites (arrow) at the outer edge of the amyloid plaque corona. B. Staining of neurons by NeuN immunoreaction reveals loss of neurons in the amyloid plaque territory. C. Parvalbumin‐immunoreactive neurons and neurites are largely preserved except in the plaque core. D. GFAP‐reactive astrocytes in the marginal zone of an amyloid plaque. Fine astrocytic processes additionally penetrate the plaque corona. E. Glial glutamate transporter 1 in contrast to GFAP predominantly reveals an increased plaque‐associated immunoreactivity in the corona. F. Increased microglia IBA‐1 immunoreactivity in the coronal plaque zone. Scale bar in A–C = 50 μm and in D,E = 25 μm.

Figure S2. Profound effects on the ECM demonstrated using biotinylated WFA lectin (A–D) as well as aggrecan antibody (E–H) on somatosensory cortex 1 (S1). An obvious decline in WFA reactivity can be detected with increasing PMD (B–D), whereas aggrecan reactivity seems to be largely unaffected (F–H) even under prolonged PMD (warm condition). Scale bar A–H = 50 μm.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona, for the provision of human brain tissue. The Brain Donation Program is supported by the NIA (P30 AG19610 Arizona AD Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer's Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05–901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation GRK 1097 “INTERNEURO,” the EU‐Project “Neuropro” (Grant Agreement no. 223077), COST Action BM1001 “Brain Extracellular Matrix in Health and Disease”, the Alzheimer Forschungsinitiative e.V. (AFI #11861) to M. Morawski and the MD/PhD program at the Universität Leipzig to M. Morawski. Further, we would like to thank Dr. Max Holzer for the helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams I, Brauer K, Arélin C, Härtig W, Fine A, Mäder M et al (2001) Perineuronal nets in the rhesus monkey and human basal forebrain including basal ganglia. Neuroscience 108:285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ajmo JM, Bailey LA, Howell MD, Cortez LK, Pennypacker KR, Mehta HN et al (2010) Abnormal post‐translational and extracellular processing of brevican in plaque‐bearing mice over‐expressing APPsw. J Neurochem 113:784–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akiyama H, Tooyama I, Kawamata T, Ikeda K, McGeer PL (1993) Morphological diversities of CD44 positive astrocytes in the cerebral cortex of normal subjects and patients with Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 632:249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alexandrescu AT (2005) Amyloid accomplices and enforcers. Protein Sci 14:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alonso AD, Zaidi T, Novak M, Barra HS, Grundke‐Iqbal I, Iqbal K (2001) Interaction of tau isoforms with Alzheimer's disease abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau and in vitro phosphorylation into the disease‐like protein. J Biol Chem 276:37967–37973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ancsin JB (2003) Amyloidogenesis: historical and modern observations point to heparan sulfate proteoglycans as a major culprit. Amyloid 10:67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arai H, Emson PC, Mountjoy CQ, Carassco LH, Heizmann CW (1987) Loss of parvalbumin‐immunoreactive neurones from cortex in Alzheimer‐type dementia. Brain Res 418:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ariga T, Miyatake T, Yu RK (2010) Role of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders: amyloidogenesis and therapeutic strategies–a review. J Neurosci Res 88:2303–2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damasio AR, van Hoesen GW (1991) The topographical and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Cereb Cortex 1:103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baig S, Wilcock GK, Love S (2005) Loss of perineuronal net N‐acetylgalactosamine in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 110:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beach TG, McGeer EG (1988) Lamina‐specific arrangement of astrocytic gliosis and senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease visual cortex. Brain Res 463:357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Roher AE, Lue L, Vedders L et al (2008) The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank 9:229–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bignami A, LeBlanc A, Perides G (1994) A role for extracellular matrix degradation and matrix metalloproteinases in senile dementia? Acta Neuropathol 87:308–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer‐related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braak H, Braak E, Kalus P (1989) Alzheimer's disease: areal and laminar pathology in the occipital isocortex. Acta Neuropathol 77:494–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brückner G, Brauer K, Härtig W, Wolff JR, Rickmann MJ, Derouiche A et al (1993) Perineuronal nets provide a polyanionic, glia‐associated form of microenvironment around certain neurons in many parts of the rat brain. Glia 8:183–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brückner G, Bringmann A, Hartig W, Koppe G, Delpech B, Brauer K (1998) Acute and long‐lasting changes in extracellular‐matrix chondroitin‐sulphate proteoglycans induced by injection of chondroitinase ABC in the adult rat brain. Exp Brain Res 121:300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brückner G, Hausen D, Härtig W, Drlicek M, Arendt T, Brauer K (1999) Cortical areas abundant in extracellular matrix chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans are less affected by cytoskeletal changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 92:791–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brückner G, Grosche J, Hartlage‐Rübsamen M, Schmidt S, Schachner M (2003) Region and lamina‐specific distribution of extracellular matrix proteoglycans, hyaluronan and tenascin‐R in the mouse hippocampal formation. J Chem Neuroanat 26:37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brückner G, Morawski M, Arendt T (2008) Aggrecan‐based extracellular matrix is an integral part of the human basal ganglia circuit. Neuroscience 151:489–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carulli D, Rhodes KE, Fawcett JW (2007) Upregulation of aggrecan, link protein 1, and hyaluronan synthases during formation of perineuronal nets in the rat cerebellum. J Comp Neurol 501:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carulli D, Pizzorusso T, Kwok J, Putignano E, Poli A, Forostyak S et al (2010) Animals lacking link protein have attenuated perineuronal nets and persistent plasticity. Brain 133:2331–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Celio MR, Heizmann CW (1981) Calcium‐binding protein parvalbumin as a neuronal marker. Nature 293:300–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crews L, Masliah E (2010) Molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet 19:R12–R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeWitt DA, Silver J, Canning DR, Perry G (1993) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans are associated with the lesions of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol 121:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diepholder HM, Schwechheimer K, Mohadjer M, Knoth R, Volk B (1991) A clinicopathologic and immunomorphologic study of 13 cases of ganglioglioma. Cancer 68:2192–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dityatev A, Schachner M, Sonderegger P (2010) The dual role of the extracellular matrix in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci 11:735–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dityatev A, Rusakov DA (2011) Molecular signals of plasticity at the tetrapartite synapse. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21:353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dityatev A, Schachner M (2003) Extracellular matrix molecules and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:456–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dityatev A, Seidenbecher CI, Schachner M (2010) Compartmentalization from the outside: the extracellular matrix and functional microdomains in the brain. Trends Neurosci 33:503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dong H, Martin MV, Chambers S, Csernansky JG (2007) Spatial relationship between synapse loss and beta‐amyloid deposition in Tg2576 mice. J Comp Neurol 500:311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferrer I, Soriano E, Tuñón T, Fonseca M, Guionnet N (1991) Parvalbumin immunoreactive neurons in normal human temporal neocortex and in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci 106:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frautschy SA, Horn DL, Sigel JJ, Harris‐White ME, Mendoza JJ, Yang F et al (1998) Protease inhibitor coinfusion with amyloid beta‐protein results in enhanced deposition and toxicity in rat brain. J Neurosci 18:8311–8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frischknecht R, Heine M, Perrais D, Seidenbecher CI, Choquet D, Gundelfinger ED (2009) Brain extracellular matrix affects AMPA receptor lateral mobility and short‐term synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci 12:897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Genedani S, Agnati LF, Leo G, Buzzega D, Maccari F, Carone C et al (2010) beta‐Amyloid fibrillation and/or hyperhomocysteinemia modify striatal patterns of hyaluronic acid and dermatan sulfate: possible role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 7:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giamanco KA, Morawski M, Matthews RT (2010) Perineuronal net formation and structure in aggrecan knockout mice. Neuroscience 170:1314–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goedert M (1996) Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 777:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goedert M, Jakes R, Crowther RA, Cohen P, Vanmechelen E, Vandermeeren M et al (1994) Epitope mapping of monoclonal antibodies to the paired helical filaments of Alzheimer's disease: identification of phosphorylation sites in tau protein. Biochem J 301:871–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Härtig W, Brauer K, Brückner G (1992) Wisteria floribunda agglutinin‐labelled nets surround parvalbumin‐containing neurons. Neuroreport 3:869–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Härtig W, Brauer K, Bigl V, Brückner G (1994) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan‐immunoreactivity of lectin‐labeled perineuronal nets around parvalbumin‐containing neurons. Brain Res 635:307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Härtig W, Derouiche A, Welt K, Brauer K, Grosche J, Mader M et al (1999) Cortical neurons immunoreactive for the potassium channel Kv3.1b subunit are predominantly surrounded by perineuronal nets presumed as a buffering system for cations. Brain Res 842:15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Härtig W, Klein C, Brauer K, Schüppel KF, Arendt T, Bigl V et al (2001) Hyperphosphorylated protein tau is restricted to neurons devoid of perineuronal nets in the cortex of aged bison. Neurobiol Aging 22:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hartlage‐Rübsamen M, Morawski M, Waniek A, Jäger C, Zeitschel U, Koch B et al (2011) Glutaminyl cyclase contributes to the formation of focal and diffuse pyroglutamate (pGlu)‐Aβ deposits in hippocampus via distinct cellular mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 121:705–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hirschfield GM, Hawkins PN (2003) Amyloidosis: new strategies for treatment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 35:1608–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hobohm C, Günther A, Grosche J, Rossner S, Schneider D, Brückner G (2005) Decomposition and long‐lasting downregulation of extracellular matrix in perineuronal nets induced by focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Neurosci Res 80:539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hockfield S, Kalb RG, Zaremba S, Fryer H (1990) Expression of neural proteoglycans correlates with the acquisition of mature neuronal properties in the mammalian brain. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 55:505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hockfield S, Tootell RB, Zaremba S (1990) Molecular differences among neurons reveal an organization of human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:3027–3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hof PR, Cox K, Young WG, Celio MR, Rogers J, Morrison JH (1991) Parvalbumin‐immunoreactive neurons in the neocortex are resistant to degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 50:451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ittner LM, Götz J (2011) Amyloid‐β and tau–a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 12:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jenkins HG, Bachelard HS (1988) Glycosaminoglycans in cortical autopsy samples from Alzheimer brain. J Neurochem 51:1641–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kanazawa H, Ohsawa K, Sasaki Y, Kohsaka S, Imai Y (2002) Macrophage/microglia‐specific protein Iba1 enhances membrane ruffling and Rac activation via phospholipase C‐gamma ‐dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 277:20026–20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kobayashi K, Emson PC, Mountjoy CQ (1989) Vicia villosa lectin‐positive neurones in human cerebral cortex. Loss in Alzheimer‐type dementia. Brain Res 498:170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kochlamazashvili G, Henneberger C, Bukalo O, Dvoretskova E, Senkov O, Lievens PM et al (2010) The extracellular matrix molecule hyaluronic acid regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity by modulating postsynaptic L‐type Ca(2+) channels. Neuron 67:116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Köppe G, Brückner G, Härtig W, Delpech B, Bigl V (1997) Characterization of proteoglycan‐containing perineuronal nets by enzymatic treatments of rat brain sections. Histochem J 29:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lauderback CM, Hackett JM, Huang FF, Keller JN, Szweda LI, Markesbery WR et al (2001) The glial glutamate transporter, GLT‐1, is oxidatively modified by 4‐hydroxy‐2‐nonenal in the Alzheimer's disease brain: the role of Abeta1‐42. J Neurochem 78:413–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Leuba G, Kraftsik R, Saini K (1998) Quantitative distribution of parvalbumin, calretinin, and calbindin D‐28k immunoreactive neurons in the visual cortex of normal and Alzheimer cases. Exp Neurol 152:278–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lewis DA, Campbell MJ, Terry RD, Morrison JH (1987) Laminar and regional distributions of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in Alzheimer's disease: a quantitative study of visual and auditory cortices. J Neurosci 7:1799–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mai JK, Assheuer J, Paxinos G (2004) Atlas of the Human Brain, 2nd edn. Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Martín‐de‐Saavedra MD, del Barrio L, Cañas N, Egea J, Lorrio S, Montell E et al (2011) Chondroitin sulfate reduces cell death of rat hippocampal slices subjected to oxygen and glucose deprivation by inhibiting p38, NFκB and iNOS. Neurochem Int 58:676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matthews RT, Gary SC, Zerillo C, Pratta M, Solomon K, Arner EC et al (2000) Brain‐enriched hyaluronan binding (BEHAB)/brevican cleavage in a glioma cell line is mediated by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family member. J Biol Chem 275:22695–22703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McRae PA, Rocco MM, Kelly G, Brumberg JC, Matthews RT (2007) Sensory deprivation alters aggrecan and perineuronal net expression in the mouse barrel cortex. J Neurosci 27:5405–5413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM et al (1991) The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 41:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Miyata S, Nishimura Y, Nakashima T (2007) Perineuronal nets protect against amyloid beta‐protein neurotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Brain Res 1150:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Morawski M, Brückner MK, Riederer P, Brückner G, Arendt T (2004) Perineuronal nets potentially protect against oxidative stress. Exp Neurol 188:309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Morawski M, Reinert T, Bruckner G, Wagner FE, Arendt T, Troger W (2004) The binding of iron to perineuronal nets: a combined nuclear microscopy and Mossbauer study. Hyperfine Interact 159:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Morawski M, Brückner G, Jäger C, Seeger G, Arendt T (2010) Neurons associated with aggrecan‐based perineuronal nets are protected against tau pathology in subcortical regions in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 169:1347–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Morawski M, Brückner G, Jäger C, Seeger G, Künzle H, Arendt T (2010) Aggrecan‐based extracellular matrix shows unique cortical features and conserved subcortical principles of mammalian brain organization in the Madagascan lesser hedgehog tenrec (Echinops telfairi Martin, 1838). Neuroscience 165:831–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Morawski M, Hartlage‐Rübsamen M, Jäger C, Waniek A, Schilling S, Schwab C et al (2010) Distinct glutaminyl cyclase expression in Edinger‐Westphal nucleus, locus coeruleus and nucleus basalis Meynert contributes to pGlu‐Abeta pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 120:195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Morawski M, Pavlica S, Seeger G, Grosche J, Kouznetsova E, Schliebs R et al (2010) Perineuronal nets are largely unaffected in Alzheimer model Tg2576 mice. Neurobiol Aging 31:1254–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Muir EM, Adcock KH, Morgenstern DA, Clayton R, von Stillfried N, Rhodes K et al (2002) Matrix metalloproteases and their inhibitors are produced by overlapping populations of activated astrocytes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 100:103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Murakami T, Ohtsuka A, Su WD, Taguchi T, Oohashi T, Abe K et al (1999) The extracellular matrix in the mouse brain: its reactions to endo‐alpha‐N‐acetylgalactosaminidase and certain other enzymes. Arch Histol Cytol 62:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nakada M, Miyamori H, Kita D, Takahashi T, Yamashita J, Sato H et al (2005) Human glioblastomas overexpress ADAMTS‐5 that degrades brevican. Acta Neuropathol 110:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Neame PJ, Barry FP (1994) The link proteins. EXS 70:53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Okamoto M, Mori S, Ichimura M, Endo H (1994) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans protect cultured rat's cortical and hippocampal neurons from delayed cell death induced by excitatory amino acids. Neurosci Lett 172:51–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Park JB, Kwak H, Lee S (2008) Role of hyaluronan in glioma invasion. Cell Adhes Migr 2:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Paxinos G, Huang XF, Toga AW (2000) The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Perl DP (2010) Neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Mt Sinai J Med 77:32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pizzorusso T, Medini P, Berardi N, Chierzi S, Fawcett J, Maffei L (2002) Reactivation of ocular dominance plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science 298:1248–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Poirier K, Saillour Y, Bahi‐Buisson N, Jaglin XH, Fallet‐Bianco C, Nabbout R et al (2010) Mutations in the neuronal β‐tubulin subunit TUBB3 result in malformation of cortical development and neuronal migration defects. Hum Mol Genet 19:4462–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Porzig R, Singer D, Hoffmann R (2007) Epitope mapping of mAbs AT8 and Tau5 directed against hyperphosphorylated regions of the human tau protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358:644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Qiu WQ, Ye Z, Kholodenko D, Seubert P, Selkoe DJ (1997) Degradation of amyloid beta‐protein by a metalloprotease secreted by microglia and other neural and non‐neural cells. J Biol Chem 272:6641–6646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rauch U (2004) Extracellular matrix components associated with remodeling processes in brain. Cell Mol Life Sci 61:2031–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rees MD, Kennett EC, Whitelock JM, Davies MJ (2008) Oxidative damage to extracellular matrix and its role in human pathologies. Free Radic Biol Med 44:1973–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rosenberg GA (2009) Matrix metalloproteinases and their multiple roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol 8:205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Satoh K, Suzuki N, Yokota H (2000) ADAMTS‐4 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs) is transcriptionally induced in beta‐amyloid treated rat astrocytes. Neurosci Lett 289:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Scheff SW, Price DA (1993) Synapse loss in the temporal lobe in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 33:190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Schilling S, Zeitschel U, Hoffmann T, Heiser U, Francke M, Kehlen A et al (2008) Glutaminyl cyclase inhibition attenuates pyroglutamate Abeta and Alzheimer's disease‐like pathology. Nat Med 14:1106–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Seeger G, Lüth HJ, Winkelmann E, Brauer K (1996) Distribution patterns of Wisteria floribunda agglutinin binding sites and parvalbumin‐immunoreactive neurons in the human visual cortex: a double‐labelling study. J Hirnforsch 37:351–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Syková E, Vorísek I, Antonova T, Mazel T, Meyer‐Luehmann M, Jucker M et al (2005) Changes in extracellular space size and geometry in APP23 transgenic mice: a model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:479–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R et al (1991) Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer's disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 30:572–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Tortorella MD, Arner EC, Hills R, Gormley J, Fok K, Pegg L et al (2005) ADAMTS‐4 (aggrecanase‐1): N‐terminal activation mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys 444:34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Urbanc B, Cruz L, Le R, Sanders J, Ashe KH, Duff K et al (2002) Neurotoxic effects of thioflavin S‐positive amyloid deposits in transgenic mice and Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:13990–13995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Virgintino D, Perissinotto D, Girolamo F, Mucignat MT, Montanini L, Errede M et al (2009) Differential distribution of aggrecan isoforms in perineuronal nets of the human cerebral cortex. J Cell Mol Med 13:3151–3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Washbourne P, Schiavo G, Montecucco C (1995) Vesicle‐associated membrane protein‐2 (synaptobrevin‐2) forms a complex with synaptophysin. Biochem J 305(Pt 3):721–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ (1991) Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in thesubdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec 231:482–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wiedenmann B, Franke WW (1985) Identification and localization of synaptophysin, an integral membrane glycoprotein of Mr 38 000 characteristic of presynaptic vesicles. Cell 41:1017–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Woodhouse A, Vickers JC, Adlard PA, Dickson TC (2009) Dystrophic neurites in TgCRND8 and Tg2576 mice mimic human pathological brain aging. Neurobiol Aging 30:864–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wyss‐Coray T, Loike JD, Brionne TC, Lu E, Anankov R, Yan F et al (2003) Adult mouse astrocytes degrade amyloid‐beta in vitro and in situ . Nat Med 9:453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Yasuhara O, Akiyama H, McGeer EG, McGeer PL (1994) Immunohistochemical localization of hyaluronic acid in rat and human brain. Brain Res 635:269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yin K, Cirrito JR, Yan P, Hu X, Xiao Q, Pan X et al (2006) Matrix metalloproteinases expressed by astrocytes mediate extracellular amyloid‐beta peptide catabolism. J Neurosci 26:10939–10948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Profound neuronal (A–C) and glial (D,E) alterations related to amyloid plaque pathology in the visual cortex of AD patients indicating the advanced stage of disease. The organization of amyloid plaque is shown in A, D, E and F indicating the core (asterisks), the corona (filled circle) and the marginal plaque zone (filled triangle). A. Synaptobrevin immunoreaction indicates dystrophic neurites (arrow) at the outer edge of the amyloid plaque corona. B. Staining of neurons by NeuN immunoreaction reveals loss of neurons in the amyloid plaque territory. C. Parvalbumin‐immunoreactive neurons and neurites are largely preserved except in the plaque core. D. GFAP‐reactive astrocytes in the marginal zone of an amyloid plaque. Fine astrocytic processes additionally penetrate the plaque corona. E. Glial glutamate transporter 1 in contrast to GFAP predominantly reveals an increased plaque‐associated immunoreactivity in the corona. F. Increased microglia IBA‐1 immunoreactivity in the coronal plaque zone. Scale bar in A–C = 50 μm and in D,E = 25 μm.

Figure S2. Profound effects on the ECM demonstrated using biotinylated WFA lectin (A–D) as well as aggrecan antibody (E–H) on somatosensory cortex 1 (S1). An obvious decline in WFA reactivity can be detected with increasing PMD (B–D), whereas aggrecan reactivity seems to be largely unaffected (F–H) even under prolonged PMD (warm condition). Scale bar A–H = 50 μm.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item