Abstract

One-fourth of Plasmodium falciparum proteins have asparagine repeats that increase the propensity for aggregation, especially at elevated temperatures that occur routinely in malaria-infected patients. We report that a Plasmodium Asn repeat-containing protein (PFI1155w) formed aggregates in mammalian cells at febrile temperatures, as did a yeast Asn/Gln-rich protein (Sup35). Co-expression of the cytoplasmic P. falciparum heat shock protein 110 (PfHsp110c) prevented aggregation. Human or yeast orthologs were much less effective. All-Asn and all-Gln versions of Sup35 were protected from aggregation by PfHsp110c, suggesting that this chaperone is not limited to handling runs of Asn. PfHsp110c gene knockout parasites were not viable and conditional knockdown parasites died slowly in the absence of protein-stabilizing ligand. When exposed to brief heat shock, these knockdowns were unable to prevent aggregation of PFI1155w or Sup35 and died rapidly. We conclude that PfHsp110c protects the parasite from harmful effects of its asparagine repeat-rich proteome during febrile episodes.

The deadly malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, has a proteome that is replete with amino acid repeats; the majority of these repeats consist of asparagine (Asn) residues1,2. One in four proteins in the P. falciparum proteome have Asn repeat-rich sequences, comprising up to 83 Asn residues and an average size of 37 residues3. There can be multiple repeats in a given protein. The presence of Asn-rich sequences in proteins is known to increase propensity for aggregate formation4–6. Formation of aggregates is enhanced under heat shock stress conditions due to an increase in protein unfolding7,8. In a recent survey of prion proteins in yeast, numerous Asn-rich sequences were found to form aggregates4. Prion-like aggregates have been shown to be responsible for the inheritance of several phenotypes in yeast9,10, to have a functional biological role in bacteria11, to be important for persistence of synaptic facilitation12 and to be vital for antiviral innate immunity13. While such regulated aggregation of proteins is benign or beneficial, unregulated aggregation of proteins can lead to cell death6,14. The malaria parasite is able to thrive with an Asn repeat-rich proteome in face of the periodic heat shock stress that is a hallmark of clinical malaria. Patients suffer recurrent bouts of fever, often exceeding 40°C and lasting several hours at a time. The ability of P. falciparum to survive this insult is likely due to processes that mask Asn repeat-rich protein aggregation.

Certain chaperones, particularly heat shock proteins (Hsps), have been shown to play a vital role in controlling aggregate formation15,16. In vitro, these chaperones act in concert to refold proteins and unfold preformed aggregates17. The Hsp70-Hsp110-Hsp40 network refolds proteins via repeated cycles of binding and release of unfolded proteins by Hsp70 that is governed by its ADP or ATP bound state, respectively15,16. Hsp110 acts as a nucleotide exchange factor for Hsp70, exchanging ADP for ATP and thereby completing the refolding cycle18–21. Hsp110 can also bind unfolded proteins, via its substrate binding domain, but the role of this binding event in the refolding cycle is unclear22–24 and its biological function remains undefined. Recently, mammalian Hsp110 was found to localize with aggregates in HEK293T cells but the significance of the association is not understood14. Drosophila Hsp110 was identified in a genome-wide RNAi screen as a mitigating factor for aggregation of Huntingtin protein25. This chaperone system clearly plays a role in unfolded protein handling, but its capacity is easily overwhelmed by the expression of aggregation-prone proteins, especially under heat shock conditions. Heat shock stress increases the propensity of proteins to unfold, enhancing the formation of aggregates7,8.

We show here that the cytoplasmic Hsp110 of P. falciparum (PfHsp110c) is able to prevent aggregation of Asn repeat-rich proteins in cultured malaria parasites and in mammalian cells. The P. falciparum chaperone is much better at this than orthologs from yeast or humans. We conclude that PfHsp110c, in particular its substrate binding activity, is vital for proteostasis of the Asn repeat-rich proteome of P. falciparum and propose that its presence allows the propagation of these repeats within the parasite proteome.

RESULTS

A P. falciparum Asn rich protein aggregates in human cells

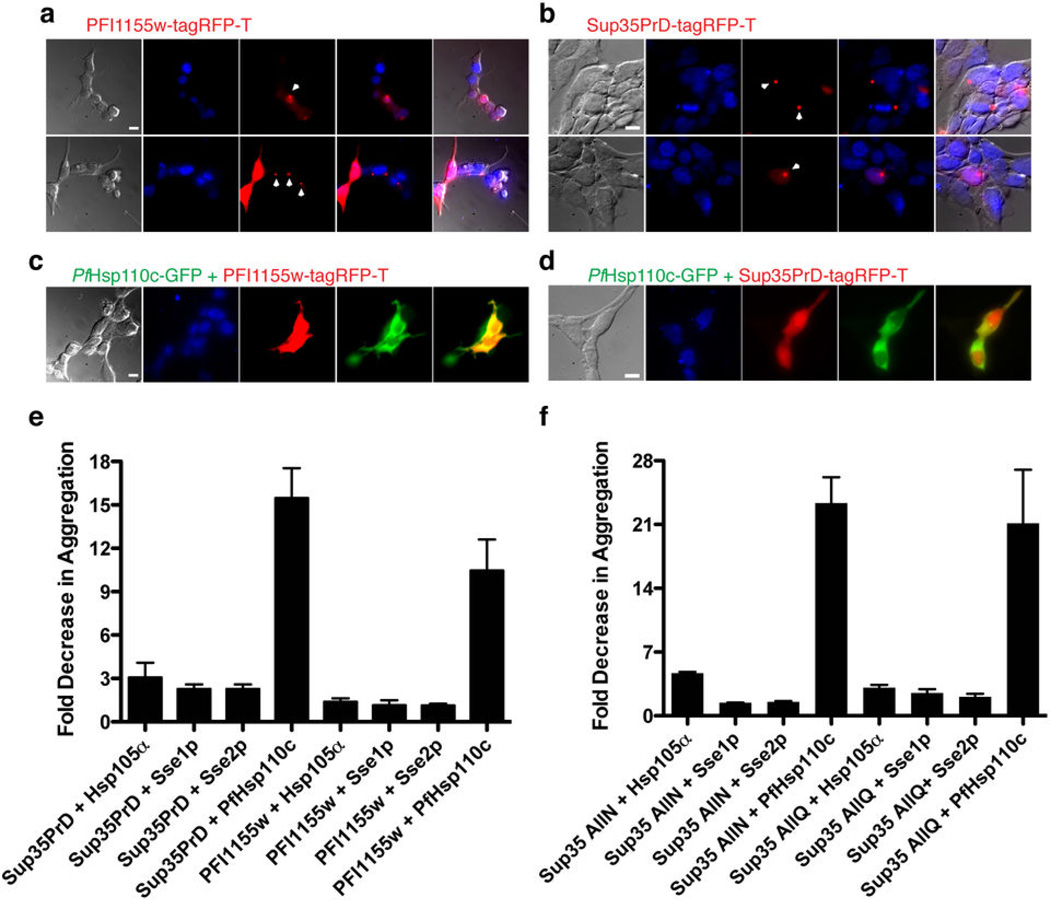

Aggregation of Asn repeat-rich proteins has not been observed within P. falciparum and we have reported that the presence of these repeats within a protein does not seem to affect its cellular function or location, even under heat shock26. This suggested that the parasite chaperone network has adapted to mask the aggregation propensity of its Asn repeat-rich proteome or that the parasite Asn repeat-rich proteins are not capable of aggregating even during febrile episodes. To distinguish between these possibilities, we transiently transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells with a P. falciparum protein that contains a stretch of 83 Asn residues (PlasmoDB ID: PF3D7_0923500 or PFI1155w). For comparison, we transfected HEK293T cells with the N-terminal Asn/Gln-rich prion-forming domain (PrD, aa 1-125) of the yeast protein Sup35 (Sup35PrD)9,27. Each was fused to a monomeric derivative of red fluorescent protein (tagRFP-T)28 The transfected HEK293T cells were incubated at 40°C for 6 hours and then assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1a, b). Protein aggregation, observed as distinct fluorescent foci, was seen in a large proportion of the HEK293T cells expressing either Asn-rich protein (Fig. 1a, b and Fig. S1a). The fluorescent fusion protein, tagRFP-T, expressed alone in HEK293T cells did not form aggregates (Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

PfHsp110c prevents aggregation of Asn-rich proteins in heat-shocked mammalian cells. (a, b) The Asn repeat-rich parasite protein, PFI1155w (a) or the prion-forming domain of Sup35PrD (b) was fused to tagRFP-T and expressed in HEK293T cells. The cells were fixed and observed by fluorescence microscopy. The arrowheads point to fluorescent foci of tagRFP-T fusion protein, indicating aggregation. Images from left to right are phase, DAPI, RFP, fluorescence merge and all merge. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (c, d) PfHsp110c-GFP was co-expressed with PFI1155w-tagRFP-T (c) or Sup35PrD-tagRFP-T (d) in HEK293T cells. The cells were treated as in (a). Scale bars as in (a). Images from left to right are phase, DAPI, RFP, GFP and RFP-GFP merge. (e, f) The reduction in aggregate formation as observed by blinded quantification of fluorescent foci of tagRFP-T fusions for cells co-expressing Hsp110-GFP fusions (Supplementary Fig. 1). The y-axis represents the ratio of the fraction of cells showing fluorescent foci that express the Asn or Gln rich tagRFP-T fusion protein alone to the fraction of cells showing fluorescent foci that co-express Hsp110 proteins with the Asn or Gln rich tagRFP-T fusion protein. Greater than 300 double-transfected cells were assessed under each condition. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n≥3). The raw data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a.

PfHsp110c prevents protein aggregation in human cells

We tested the ability of Hsp110 proteins from yeast, human and P. falciparum to prevent aggregation. Two Hsp110 proteins in P. falciparum were identified via sequence homology to human and yeast Hsp110 proteins (Fig. S3). One of the P. falciparum Hsp110 proteins (PF3D7_134200 or MAL13P1.540) has a predicted signal sequence as well as an ER retention signal (Fig. S3). We focused our efforts on the cytoplasmic Hsp110 (PF3D7_0708800 or PF07_0033, referred to as PfHsp110c). Co-expression of a PfHsp110c-GFP fusion with PFI1155w or Sup35PrD in heat-shocked HEK293T cells gave uniform cytoplasmic distribution of the Asn-rich proteins (Fig. 1c, d). In contrast, substituting orthologs from human (Hsp105α) or yeast (Sse1p or Sse2p) for PfHsp110c allowed substantial formation of fluorescent foci in co-transfected cells (Fig. S1b-g). All fusion proteins were expressed at comparable levels in HEK293T cells (Fig. S1h, i).

The formation of protein aggregates was quantified (Fig. 1e and Fig. S1a). While Hsp105α, Sse1p and Sse2p co-expression gave 2–3-fold reductions in the appearance of Sup35PrD or PFI1155w protein aggregates after heat shock, co-expression of PfHsp110c reduced the formation of protein aggregates by 10–15 fold compared to Asn-rich protein fusion construct alone (Fig. 1e). We conclude that Hsp110 homologs can reduce aggregation of Asn-rich proteins, and that PfHsp110c is substantially better at doing so than its yeast and human counterparts.

To determine if PfHsp110c is selective for Asn-rich proteins, all Asn or all Gln versions of Sup35PrD5, in which every Gln residue in Sup35PrD was changed to Asn or every Asn residue in Sup35PrD was changed to Gln, were substituted for the wild-type Sup35PrD in the HEK293T transfection experiment. PfHsp110c protected against aggregation of both versions and to a greater extent than its homologs in all cases (Fig. 1f). PfHsp110c appears to have a general aggregation protection function.

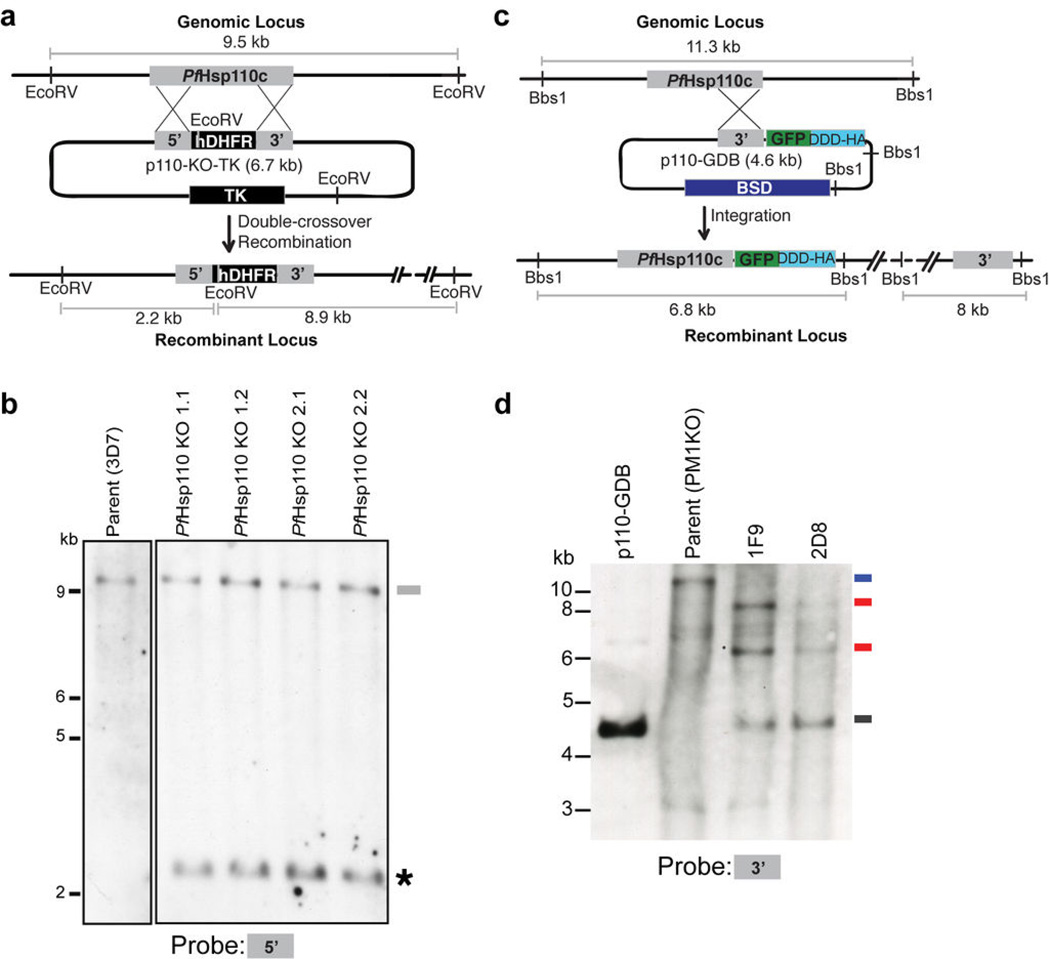

PfHsp110c is an essential gene

To investigate the role of PfHsp110c in the intraerythrocytic life cycle of the malaria parasite, we attempted to knock out the PfHsp110c gene using a double crossover homologous recombination approach29 (Fig. 2a). Successful double crossover integration of the hDHFR drug resistance cassette into the PfHsp110c gene was observed in all clones isolated from independent transfections (Fig. S4). However, in the Southern blot probed with the 5’ homologous region utilized for generating the knockout, we observed a second band corresponding to an uninterrupted endogenous gene (Fig. 2b). The data suggest that the PfHsp110c gene underwent a duplication event and the hDHFR selection cassette integrated into one copy. Locus mapping showed that duplication was limited to the PfHsp110c gene and did not extend to neighboring genes (Fig. S4c). The inability to obtain disruptants of the PfHsp110c gene without gene duplication suggests an essential function for this gene30.

Figure 2.

Knockout of PfHsp110c results in gene duplication. (a) Scheme showing the strategy utilized to knock out the PfHsp110c gene via double crossover homologous recombination. Plasmid (p110-KO-TK) containing a positive drug selection marker, human dihydrofolate reductase (hDHFR) and a negative drug selection marker, thymidine kinase (TK) was transfected into the parent strain, 3D7. EcoRV restriction sites used to detect integration along with the expected sizes are indicated. (b) Southern blot of genomic DNA digested with EcoRV and probed with the 5’ region of the PfHsp110c gene utilized for homologous recombination. The bands expected for double crossover integration of the 5’ homologous region were seen in all clones (*). The band expected for the undisrupted PfHsp110c gene in the parental line, 3D7, was also seen in all clones (—). (c) Scheme showing the strategy utilized to fuse the RFA-tag to the 3’ end of the PfHsp110c gene via single crossover homologous recombination. Plasmid (p110-GDB) containing the blasticidin (BSD) resistance cassette, for positive drug selection, was transfected into the parental strain, PM1KO. BbsI restriction sites along with the probe used to detect integration and the expected sizes are indicated. (d) Southern blots of genomic and plasmid DNA digested with BbsI. Bands expected from a single crossover integration of the RFA-tag into the 3’ end of the PfHsp110c gene were observed in both clones, 1F9 and 2D8, isolated from the two independent transfections ( ). The band expected for the digested plasmid was also seen in both clones (

). The band expected for the digested plasmid was also seen in both clones ( ), suggesting that a plasmid concatamer integrated into the gene, a common occurrence in P. falciparum. A single band was observed for the parental strain (PM1KO,

), suggesting that a plasmid concatamer integrated into the gene, a common occurrence in P. falciparum. A single band was observed for the parental strain (PM1KO,  ) that was absent in the integrant clones.

) that was absent in the integrant clones.

The study of essential genes in the haploid malaria parasite has been enhanced by degradation-domain based conditional expression systems31–33. We recently reported use of a regulated fluorescent affinity (RFA) tag based on the Escherichia coli DHFR degradation domain (DDD)26. In the absence of the folate analog trimethoprim (TMP) the fusion protein is unstable and thus targeted for degradation by the proteasome. In the presence of TMP, the fusion protein is stabilized and able to carry out its normal biological function. The PfHsp110c gene was RFA-tagged via a single crossover homologous recombination strategy (Fig. 2c, d). Clones isolated from independent transfections were used for further analysis (1F9 and 2D8).

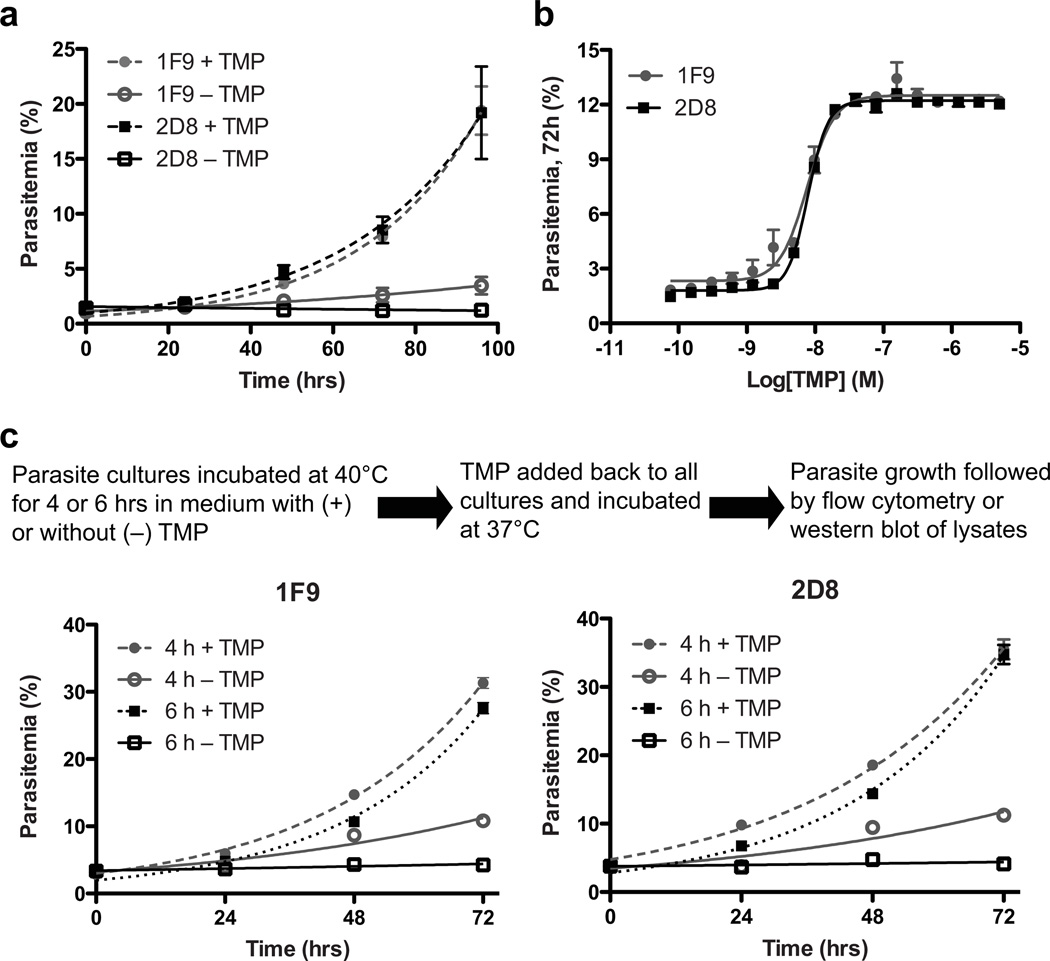

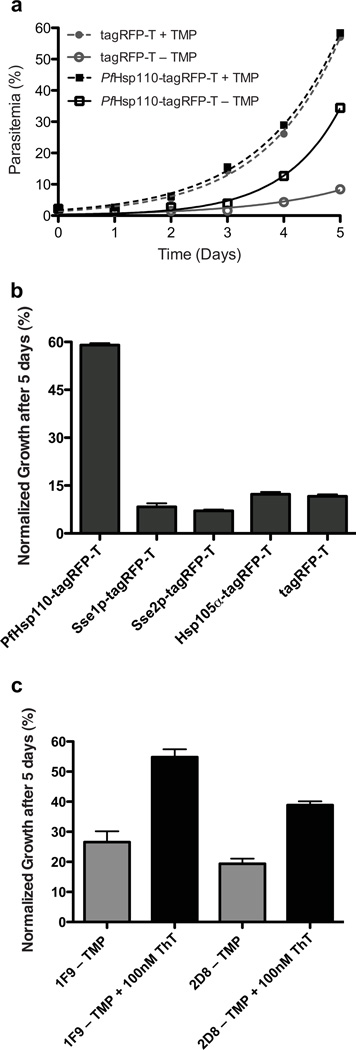

Growth of PfHsp110c-RFA parasite lines in the absence or presence of 10 µM TMP was monitored over several days by flow cytometry (Fig. 3a). PfHsp110c-RFA parasites did not grow in the absence of TMP and by 48 hours no evidence of live parasites was seen by microscopy. Growth of PfHsp110c-RFA parasite lines was TMP concentration dependant (Fig. 3b). We conclude that PfHsp110c provides an essential function to the blood stage parasites that is disrupted upon TMP removal due to destabilization of the RFA tag.

Figure 3.

PfHsp110c is essential and is required for surviving febrile temperatures. (a) Asynchronous PfHsp110c-RFA parasite clones, 1F9 and 2D8, were grown with or without 10 µM TMP and their growth was monitored over 5 days via flow cytometry. Data are fit to an exponential growth equation and are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3). (b) Asynchronous PfHsp110c-RFA parasite clones, 1F9 and 2D8, were incubated in different TMP concentrations and their growth was monitored after 3 days by flow cytometry. Data are fit to a dose-response equation and are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3). (c) Asynchronous PfHsp110c-RFA parasite clones, 1F9 and 2D8, were subjected to heat shock using the protocol shown, permissive conditions were restored and their growth was monitored over 3 days by flow cytometry. Data are fit to an exponential growth equation and are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3). For each experiment, parasites were subcultured with fresh erythrocytes at day 3 and parasitemia is calculated accounting for culture dilution. Media were changed every day.

PfHsp110c is required for surviving heat shock

High fever, which occurs periodically in malaria patients, is a cellular stress that results in a global tendency towards unfolding of proteins7,8. Asynchronous PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were incubated at 40°C for 4–6 hours with or without TMP (Fig. 3c). After the heat shock, the parasites were transferred back into medium containing TMP and incubated at the normal growth temperature, 37°C (Fig. 3c). The recovery of PfHsp110c-RFA parasites was monitored over several days. In the absence of TMP, even a brief 4- hour incubation at 40°C severely inhibited parasite viability (Fig. 3c). In contrast, parasites incubated at 37°C for 6 hours without TMP were fully viable (Fig. S5). Indeed, cultures kept at 37°C without TMP took two days to lose viability (Fig. 3a). The results demonstrate that PfHsp110c is vital for the parasite to survive even brief febrile temperatures, suggesting a role for PfHsp110c in the proteostasis of the Asn repeat-rich parasite proteome.

TMP controls PfHsp110c-RFA function

We assessed protein levels in PfHsp110c-RFA parasites. Asynchronous PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were incubated at 37°C or 40°C in varying amounts of TMP for 24 hours. Protein levels were monitored by western blots immunoprobed for GFP, which is a component of the RFA-tag (Fig. S6a). Surprisingly, there was no TMP dose-dependent variation in PfHsp110c-RFA levels at either temperature (Fig. S6a). Additionally, parasites incubated in the absence of TMP showed no time-dependent degradation at 37°C or 40°C (Fig. S6b). In contrast, we have seen robust degradation of other RFA-tagged proteins26.

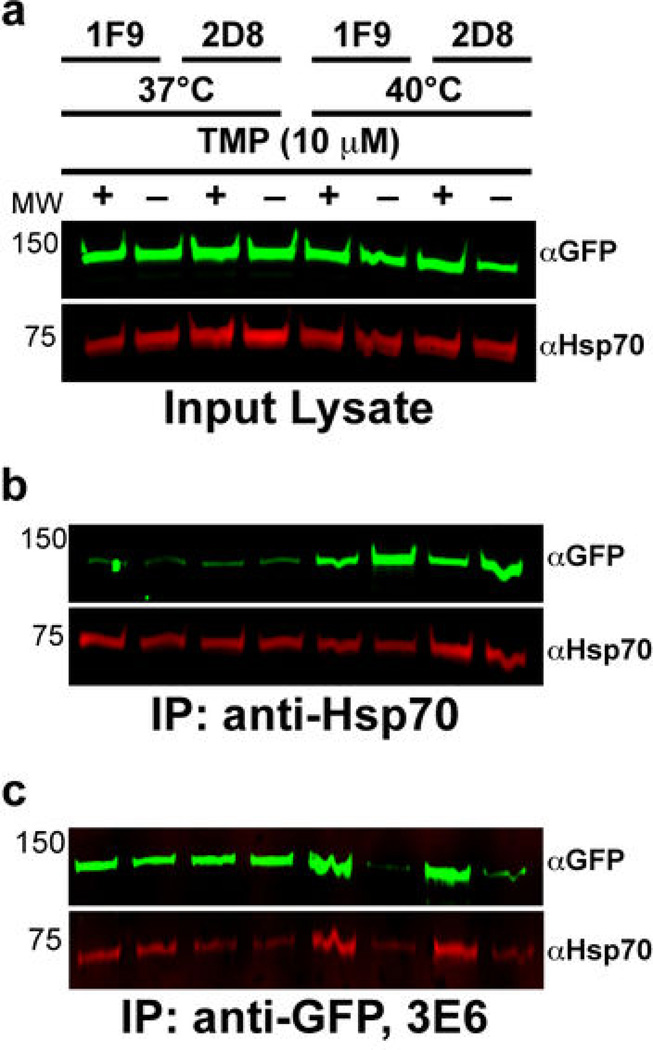

Since Hsp110 proteins act in concert with Hsp70 and their nucleotide exchange factor activity is required for Hsp70 function18–20,24, we hypothesized that in the absence of TMP the RFA-tag interferes with essential PfHsp110c interactions resulting in parasite death. We tested this model using co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments. PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were incubated at 37°C or 40°C with or without TMP for 6 hours as in Fig. 2c. Total PfHsp110c-RFA and PfHsp70 levels in lysates were stable and no degradation of PfHsp110c-RFA was observed in the absence of TMP (Fig. 4a). When PfHsp70 was immunoprecipitated from the lysates, higher amounts of PfHsp110c-RFA co-precipitated at 40°C compared to 37°C (Fig. 4b) indicating that more Hsp70-Hsp110 complex exists at the higher temperature. However, there was no TMP-dependent difference in the amount of co-precipitated PfHsp110c-RFA at either temperature. We assessed the reciprocal interaction by immunoprecipitating PfHsp110c-RFA using an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody, 3E6 (Fig. 4c) and western blotting with a second anti-GFP monoclonal antibody, JL8. The amounts of PfHsp110c-RFA and of co-precipitated PfHsp70 did not vary at 37°C with or without TMP. However, at 40°C, less PfHsp110c-RFA was immunoprecipitated in the absence of TMP and correspondingly lower amounts of PfHsp70 were seen (Fig. 4c). The data show that at 40°C without TMP, the 3E6 monoclonal anti-GFP antibody used for immunoprecipitation of PfHsp110c-RFA is unable to recognize the GFP epitope within the RFA-tag, even though the protein is clearly in the lysates (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Function of PfHsp110c-RFA is controlled by TMP. (a, b, c) PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were incubated at 37°C or 40°C with or without 10 µM TMP for 6 hours (indicated at top). PfHsp110c-RFA (using monoclonal αGFP JL8) and PfHsp70 (using polyclonal αHsp70) were detected by immunoblotting after SDS-PAGE. (a) total cell lysates, (b) immunoprecipitation of PfHsp70 using polyclonal αHsp70, (c) immunoprecipitation of PfHsp110c-RFA using monoclonal αGFP 3E6. Parasite clones 1F9 and 2D8 are indicated at the top.

Similar results were obtained using a second approach, semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE)34,35 and another anti-GFP antibody (Fig. S7). The co-IP and SDD-AGE data suggest that the unfolded DDD within the PfHsp110c-RFA is occluding the GFP within the RFA-tag by binding intramolecularly to the substrate-binding domain of PfHsp110c.

PfHsp110c and Thioflavin T rescue the knockdown phenotype

PfHsp110c-RFA parasites die upon TMP removal even though PfHsp110c-RFA protein levels do not decrease. To test if the death of PfHsp110c-RFA parasites is due to the absence of chaperone function or due to fusion protein toxicity, we episomally expressed PfHsp110c fused to tagRFP-T, under the control of the native PfHsp110c promoter in PfHsp110c-RFA parasites. The complemented PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were subjected to heat shock as in Fig. 2c. Parasites complemented with PfHsp110c-tagRFP-T but not with tagRFP-T alone were able to recover after the heat shock in the absence of TMP (Fig. 5a). The recovery is partial because plasmid maintenance is incomplete (Data not shown). In contrast, PfHsp110-RFA parasites expressing either the human Hsp105α or the yeast Hsp110 homologs (Sse1p and Sse2p) under the control of the PfHsp110c promoter were unable to recover after heat shock in the absence of TMP (Fig. 5b). These findings support our model that the death of PfHsp110c-RFA parasites in the absence of TMP is specifically due to the loss of PfHsp110c function.

Figure 5.

The knockdown phenotype is specific and rescued only by PfHsp110c. (a) Parasites were complemented with PfHsp110c-tagRFP-T or tagRFP-T. Asynchronous complemented parasites were incubated at 40°C for 6 hours with or without 10 µM TMP as in Fig. 3c. Their recovery was monitored over 5 days by flow cytometry. Data was fit to an exponential growth equation and are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3). (b) Parasites were complemented with PfHsp110c-tagRFP-T, human Hsp105α-tagRFP-T, yeast Sse1p-tagRFP-T, Sse2p-tagRFP-T or tagRFP-T. Asynchronous complemented parasites were incubated at 40°C for 6 hours without TMP. Their recovery post-heat shock after 5 days was normalized to that of complemented PfHsp110c-RFA parasites that were heat shocked in the presence of 10 µM TMP. Parasitemia was monitored daily via flow cytometry Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3). (c) Parasites were incubated at 40°C for 6 hours without TMP with or without 100 nM Thioflavin T (ThT). Their recovery after 5 days was normalized to parasites incubated at 40°C for 6 hours with 10 µM TMP and with or without 100 nM ThT. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3).

Thioflavin T (ThT) has been utilized to monitor protein aggregation in vitro36. Recently, ThT was successfully used to maintain proteostasis and extend the life span of Caenorhabditis elegans expressing a polyglutamine protein37. PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were incubated at 40°C for 6 hours in the absence of TMP and in the presence or absence of 100 nM ThT and then allowed to recover. There was substantial and reproducible rescue of parasite growth (Fig. 5c). Higher ThT concentrations had toxic effects independent of TMP. This result suggests that in the absence of a functional PfHsp110c, parasites die due to disruption of proteostasis in its Asn repeat-rich proteome.

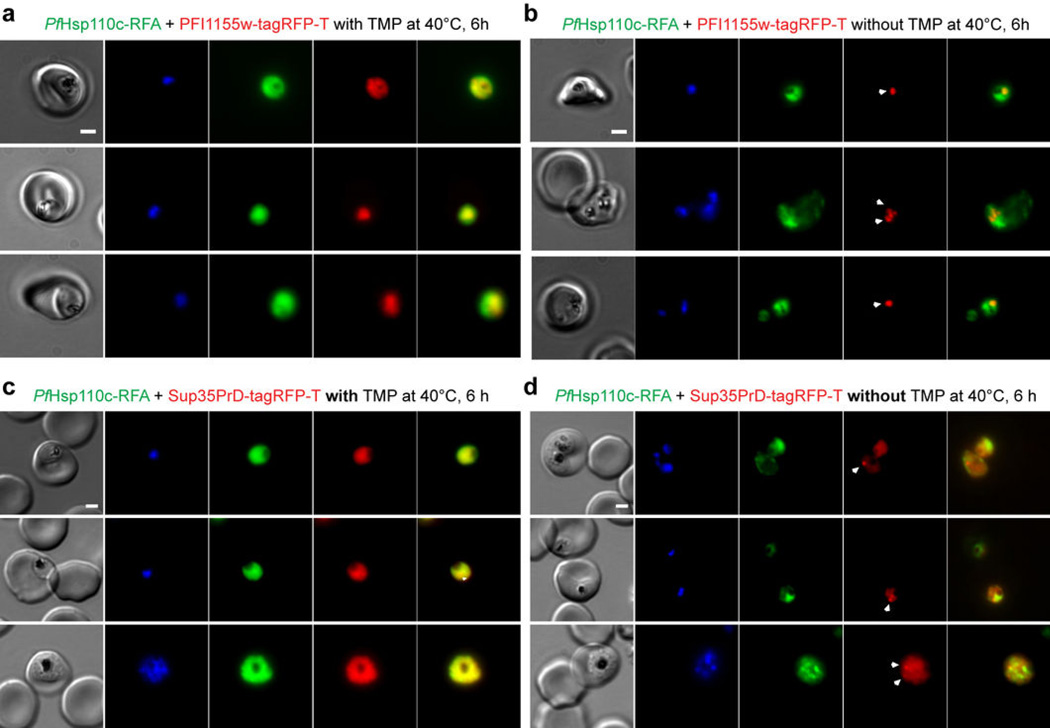

Sup35PrD and PFI1155w expression in PfHsp110c-RFA parasites

To independently test this idea, we episomally expressed PFI1155w-tagRFP-T and Sup35PrD-tagRFP-T in PfHsp110c-RFA parasite clones. Transfected parasites were incubated at 40°C for 6 hours with or without TMP (Fig. 6). Those subjected to heat shock in the presence of TMP showed uniform cytoplasmic distribution of PFI1155w-tagRFP-T (Fig. 6a) and Sup35PrD-tagRFP-T (Fig. 6c) as well as PfHsp110c-RFA (in green). However, parasites that were subjected to heat shock without TMP showed foci of PFI1155w-tagRFP-T (Fig. 6b) and Sup35PrD-tagRFP-T fluorescence (Fig. 6d) indicative of protein aggregation9,27. The distribution of PfHsp110c-RFA also was more focal upon heat shock in the absence of TMP (Fig. 6b, d) and there was minimal overlap between either PFI1155w-tagRFP-T or Sup35PrD-tagRFP-T and PfHsp110c-RFA foci (Fig. 6b, d). Expression of tagRFP-T alone in PfHsp110c-RFA lines gave diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence in all conditions (Fig. S8), showing that aggregation was dependent on the Asn-rich sequence. These observations support our model that PfHsp110c plays an essential role in preventing parasite Asn-rich protein aggregation.

Figure 6.

PfHsp110c prevents the aggregation of Asn-rich protein during febrile episodes. Live fluorescence images of PfHsp110c-RFA parasite lines expressing (a, b) the Asn repeat-rich parasite protein, PFI1155w or (c, d) the prion-forming domain from the yeast protein, Sup35 (aa1-125) fused to tagRFP-T (Sup35-tagRFP-T), incubated at 40°C for 6 hours with (a, c) or without (b, d) 10 µM TMP. The arrowheads indicate fluorescent foci of PFI1155w-tagRFP-T (b) and Sup35-tagRFP-T (d). Scale bar represents 2 µm. Images from left to right are phase, DAPI, GFP, RFP and GFP-RFP merge.

DISCUSSION

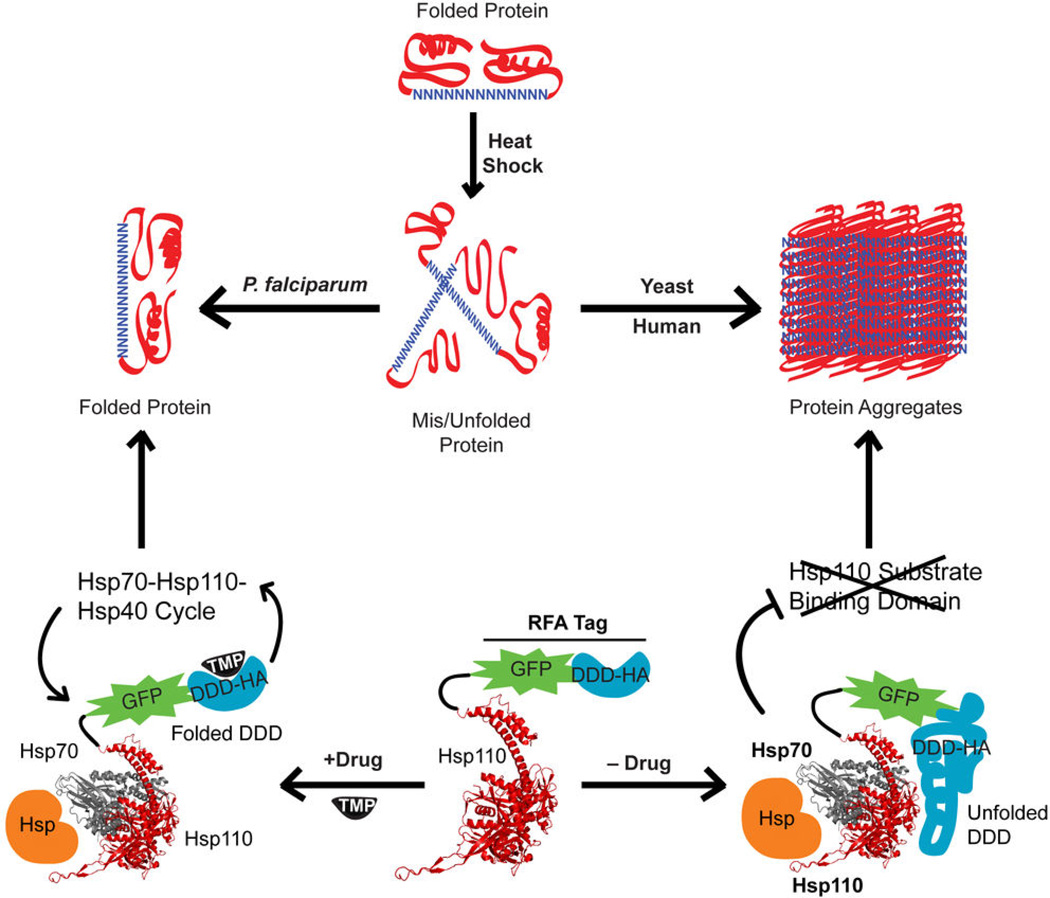

The reason for the widespread presence of Asn repeat-rich proteins in the proteome of the deadly malaria parasite, P. falciparum, remains a mystery. Indeed, proteins with large Asn-rich regions are prone to forming aggregates and prion-like fibrils4–6 and thus might be expected to reduce the fitness of malaria parasites. Furthermore, the propensity of Asn-rich proteins to aggregate is enhanced by elevated temperatures7,8, a scenario that P. falciparum parasites routinely encounter during febrile episodes that are a hallmark clinical manifestation of malaria. In this study, we have uncovered a central role of PfHsp110c in maintaining proteostasis and preventing aggregation of the Asn repeat-rich proteome of P. falciparum (Fig. 7). This chaperone is essential for parasite growth within the red blood cell (Fig. 2, 3) and its substrate binding activity is necessary for surviving even a brief exposure to febrile temperatures (Fig. 3, 4 and Fig. S7). The sequence homology of PfHsp110c to human and yeast Hsp110 proteins is only about 24%, with most of the homology in the nucleotide binding region (Fig. S3). The divergent susbtrate binding region of PfHsp110c could be responsible for the better aggregation prevention properties of the P. falciparum homolog.

Figure 7.

Proposed role of Hsp110 in maintaining an aggregate-free Asn repeat-rich parasite proteome. Proteins containing Asn-rich regions are misfolded or unfolded during heat shock. The misfolded proteins form aggregates in human and yeast cells. However, in the malaria parasite, despite an abundance of Asn repeat-rich proteins, there is no protein aggregation. The prevention of protein aggregation in P. falciparum depends upon the activity of PfHsp110c that acts in a network with other chaperones (Hsp70 and other Hsp). PfHsp110c-RFA function is dependent upon the stabilizing ligand, TMP. When TMP is present, Hsp110 can productively function in the Hsp70-Hsp110-Hsp40 cycle resulting in a stable Asn repeat-rich proteome. In the absence of TMP, the DDD within the RFA tag is unfolded. The unfolded DDD fused to Hsp110 results in the inhibition of chaperone activity. This leads to protein aggregation in the Asn repeat-rich proteome. The Hsp110 and Hsp70 structures (PDB: 3C7N) were rendered using PyMol.

The malaria parasite has to deal with regular exposure to temperatures of 40°C (during febrile episodes). We therefore tested the ability of PfHsp110c-RFA parasites to survive heat shock in the absence of the stabilizing ligand (Fig. 3c). The PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were killed within a few hours, faster than killing achieved by most antimalarial drugs. However, when we assessed cellular levels, we found that unlike other RFA-tagged parasite proteins26, PfHsp110c-RFA is not degraded in the absence of TMP (Fig. 4a and Fig. S6). PfHsp110c-RFA parasite lines were able to recover from heat shock when they were complemented with PfHsp110c but not with the human or yeast Hsp110 homologs underscoring the specificity of the phenotype (Fig. 5a, b). By using monoclonal antibodies against the GFP and HA modules of the RFA tag under more or less denaturing conditions, we were able to show that the unfolded degradation domain within the RFA-tag was occluding the epitopes of two anti-GFP monoclonal antibodies when PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were heat shocked (Fig. 4b, c and Fig. S7). Presumably, PfHsp110c-RFA was busy binding its own tag, preventing it from carrying out its usual role in binding other aggregation-prone, heat-shocked proteins and thus allowing the use of TMP to modulate chaperone function (Fig. 7). Utilizing degradation domains whose unfolding is controlled by small molecules could be a general technique to manipulate chaperone function in vivo. Our experiments failed to detect any TMP-rescued inactivation of PfHsp110c-RFA function at 37°C (Fig. 4b, c and Fig. S6). We believe that because death of PfHsp110c-RFA parasites upon removal of TMP at 37°C takes much longer (2 days) than at 40°C (4–6 hours) (Fig. 3a, c), the imbalance in proteostasis is more subtle at 37°C.

Does PfHsp110c affect proteostasis of the Asn repeat-rich parasite proteome? We investigated this question in two ways: by testing the ability of the aggregate-binding small molecule, ThT, to rescue the growth of PfHsp110c-RFA parasites heat shocked in the absence of TMP (Fig. 5c) and by expressing Asn repeat-rich proteins (PFI1155w and Sup35PrD), in PfHsp110c-RFA parasites (Fig. 6). In PfHsp110c-RFA clones, ThT was able to substantially rescue parasite viability (Fig. 5c). In addition, expression of PFI1155w or Sup35PrD in P. falciparum, did not lead to formation of aggregates (Fig. 6a, c), in contrast to what happens in yeast9,27 and in mammalian cells (Fig. 1a, b). Only in the absence of TMP (functional knockdown of PfHsp110c) and after heat shock did aggregates of PFI1155w and Sup35PrD form (Fig. 6b, d).

In HEK293T cells, Hsp110 orthologs from multiple organisms were able to modulate aggregation of the Asn-rich proteins Sup35PrD and PFI1155w but PfHsp110c did so to a much greater extent (Fig. 1). PfHsp110c prevented aggregation of not only Asn-rich proteins but also of a Gln-only version of the Sup35PrD (Fig. 1f), suggesting that its ability to handle aggregates does not depend on the sequence of the aggregating protein. These findings show that P. falciparum has evolved an Hsp110-dependent aggregation-resistance mechanism (Fig. 7). We propose that PfHsp110c may function as a cellular capacitor38, allowing the rampant expansion of Asn repeats in surface loops, where tolerated1. These repeats could then evolve over time into new functional domains of advantage to the organism.

We have demonstrated that PfHsp110c is essential for parasite survival within the host red blood cell. We have also shown that PfHsp110c is vital for maintaining proteostasis in P. falciparum (Fig. 7). In fact, PfHsp110c is able to prevent aggregation even in HEK293T cells, suggesting that its interacting partners in the chaperone network can be interchanged with distant orthologs. The identification of other chaperones that act in concert with PfHsp110c and their roles in maintaining the proteostasis of the Asn repeat-rich parasite proteome are active areas of future research. The ability to hamper the proteostasis of the imbalanced parasite proteome by inhibiting PfHsp110c function should make it an attractive target for drug development. Our findings also raise the intriguing possibility of utilizing PfHsp110c to prevent protein-misfolding diseases.

METHODS

DNA Sequences and Cloning

Genomic DNAs were isolated from P. falciparum using the Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture kit. Primers and restriction sites (New England Biolabs) used in this study are listed in Table S1. All constructs utilized in this study were confirmed by sequencing. All PCR products were inserted into the respective plasmids using the In-Fusion cloning system (Clonetech). The p110-KO-TK vector was derived from pHHT-TK vector29. A 1 kb homologous sequence from the 5’ end of the PfHsp110c gene and a 1 kb homologous sequence from the 3’ end of the PfHsp110C gene were amplified by PCR using primers in Table S1. The 5’ homologous region was introduced using SacII and BglII (New England Biolabs) restriction sites and the 3’ homologous region was introduced using ClaI and NcoI (New England Biolabs) restriction sites into the pHHT-TK vector, flanking the hDHFR cassette, to make p110-KO-TK vector. Episomal vectors for parasites were constructed from the plasmid containing Plasmepsin II in frame with GFP (pPM2GT)39 by inserting a PCR product (Table S1) comprising the hsp86 or the hsp110 promoter using AatII and XhoI (New England Biolabs) restriction sites. These vectors were further modified by replacing the hDHFR drug selection cassette with the yeast dihydroorotate dehydrogenase selection cassette40 using the BamH1 (New England Biolabs) restriction site (plasmid kindly provided by Eva Istvan). The GFP was replaced with the PCR product containing the fluorescent protein, tagRFP-T (Table S1) that was introduced into these vectors using AvrII and EagI (New England Biolabs) restriction sites. For expressing tagRFP-T alone, the PCR product comprising tagRFP-T (Table S1) was introduced into the vector using XhoI and EagI (New England Biolabs) restriction sites. The PCR products comprising Sup35PrD or PFI1155w (Table S1) were introduced, in frame with tagRFP-T, into the episomal vector with the hsp86 promoter using XhoI and AvrII restriction sites. The PfHsp110c, human Hsp105α and the two yeast Hsp110s (Sse1p and Sse2p) ORF PCR products (Table S1) were introduced, in frame with tagRFP-T, into the episomal vector containing the hsp110 promoter using XhoI and AvrII restriction sites. The PCR products comprising Sup35PrD or PFI1155w (Table S1) were inserted into pcDNA3.1 in frame with tagRFP-T using HindIII and BamHI (New England Biolabs) restriction sites. The PCR product PfHsp110C ORF in frame with GFP (Table S1) was introduced into pLexm vector using NotI and XhoI (New England Biolabs) restriction sites. The PfHsp110C ORF from this modified pLexm vector was replaced, in frame with GFP, with PCR products comprising human Hsp105α (Origene), Sse1p and Sse2p (Table S1) using NotI and AvrII restriction sites.

Cell Culture and Transfections

3D7 parasites were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with Albumax and transfected as described earlier41,42. Parasites transfected with p110-KO-TK underwent positive selection at 48h with 10 nM WR99210. After parasites appeared from WR99210 selection, they were cycled off drug for 3 weeks. Double crossover integrants were then selected by applying 10 nM WR99210 and 20 µM ganciclovir. Plasmepsin I knockout parasites26,43 transfected with p110-GDB underwent positive selection 48 h after transfection with 2.5 µg/mL BSD (Calbiochem) and 10 µM TMP (Sigma). Integration was detected after two rounds of BSD cycling. Parasites were always cultured with 10 µM TMP after it was initially introduced into the medium. In all cases, clones were isolated via limiting dilution. PfHsp110c-RFA parasites were also transfected with episomal vectors that contained a yeast dihydroorotate dehydrogenase selection marker40 allowing selection for parasites maintaining the episome using 2 µM DSM-1. For growth curves, parasites were washed twice and incubated in the required medium and temperature. Medium was changed everyday and parasites were subcultured with fresh red blood cells every three days. Human kidney cell line 293T (HEK293T) was maintained as recommended by the ATCC. HEK293T cells were transfected using the X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. After 40 h incubation with transfection reagent and plasmid DNA, cells were heat shocked for 6 hours and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS to be analyzed by microscopy.

Southern blot

Southern blots were performed with genomic DNA isolated using the Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture kit. For PfHsp110c knockout parasites, 1 µg of DNA was digested overnight with EcoRV (New England Biolabs) and integrants were screened using probes against the positive selection marker, hDHFR and the 5’ homologous region used for integration. For PfHsp110c-RFA parasites, 1 µg of DNA was digested overnight with BbsI (New England Biolabs) and integrants were screened using probes against the 3’ end of the PfHsp110c ORF. All Southern blots were performed as described earlier39.

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was carried out as described earlier26. The soluble fraction of the parasite lysates were incubated for 1 hour with 0.2 µg mouse monoclonal anti-GFP, 3E6 (Invitrogen) to immunoprecipitate PfHsp110c-RFA or 0.5 µg rabbit polyclonal anti-Hsp70 (Agrisera) to immunoprecipitate PfHsp70 and 50 µL of Protein G-linked Dynabeads (Invitrogen). The beads were then washed four times with PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The washed beads were solubilized in SDS-PAGE loading buffer (LICOR Biosciences) and fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE to be analyzed by western blot.

Western Blot and SDD-AGE

Western blots were performed as described previously26. For SDD-AGE, parasites were collected and host red blood cells were permeabilized selectively by treatment with ice-cold 0.04% Saponin in PBS for 10 minutes, followed by a wash in ice-cold PBS. Lysates from 5×107 cells were loaded per lane. SDD-AGE was performed as described34. The antibodies used in this study were mouse monoclonal anti-GFP, JL8 (1:4000) (Clonetech), mouse monoclonal anti-HA, 3F10 (1:3000) (Roche), monoclonal anti-cyclinB1, GNS1 (1: 2500) (Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti-Hsp70 (1:3000) (Agrisera) and rabbit polyclonal anti-EF1α (1: 3000)44. The primary antibodies were detected using IRDye 680CW (1: 15,000) conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (LICOR Biosciences and IRDye 800CW (1:15,000) conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (LICOR Biosciences). The western blot images were processed and analyzed using the Odyssey infrared imaging system software (LICOR Biosciences).

Flow Cytometry

Aliquots of parasite cultures (5µL) were stained with 1.5µg/mL Acridine Orange (Molecular Probes) in PBS. The fluorescence profiles of infected erythrocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD FACSCanto (BD Biosystems) or MACSQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). The parasitemia data were fit to standard growth curve or dose-response equations (nonlinear least-squares analysis) in the software package GraphPad Prism v.5.0a.

Microscopy

Live parasites were stained with 2 µM Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) as described previously39. HEK293T cells were grown on coverslips pretreated with 0.01% poly-L-lysine (Sigma), fixed and mounted on ProLong Gold with DAPI (Invitrogen), prior to microscopy. Cells were observed on an Axioscope Microscope (Carl Ziess Microimaging)42. Images were analyzed and processed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and merged images were generated using Adobe Photoshop.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Lauren Pepper for providing Sse1p and Sse2p and for helpful discussions, Heather True for providing Sup35 and anti-Sup35 antibody, Akhil Vaidya for providing DSM-1, Mike Diamond and Hyelim Cho for HEK293T cells, Roger Tsien for tagRFP-T, Niraj Tolia for pLexm, Barb Vaupel for technical assistance, Paul Sigala for comments on the manuscript, Andrey Shaw for helpful suggestions and the US National Institutes of Health (grant 1K99AI099156-01 to V.M.) for funding.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

V.M. and D.E.G. designed the study, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. V.M., A.O. and P.P. performed the experiments and interpreted the results. S.L. contributed novel reagents prior to publication and helped interpret the results.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/ naturecommunications

References

- 1.Aravind L, Iyer LM, Wellems TE, Miller LH. Plasmodium biology: genomic gleanings. Cell. 2003;115:771–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh GP, et al. Hyper-expansion of asparagines correlates with an abundance of proteins with prion-like domains in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;137:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zilversmit MM, et al. Low-complexity regions in Plasmodium falciparum: missing links in the evolution of an extreme genome. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:2198–2209. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halfmann R, et al. Opposing Effects of Glutamine and Asparagine Govern Prion Formation by Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Mol Cell. 2011;43:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters TW, Huang M. Protein aggregation and polyasparaginemediated cellular toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prion. 2007;1:144–153. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.2.4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberek K, Lewandowska A, Zietkiewicz S. Chaperones in control of protein disaggregation. EMBO J. 2008;27:328–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dill KA, Ghosh K, Schmit JD. Physical limits of cells and proteomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17876–17882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114477108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patino MM, Liu JJ, Glover JR, Lindquist S. Support for the prion hypothesis for inheritance of a phenotypic trait in yeast. Science. 1996;273:622-–626. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickner RB. [Ure3] as an Altered Ure2 Protein - Evidence for a Prion Analog in Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabate R, de Groot NS, Ventura S. Protein folding and aggregation in bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:2695–2715. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Si K, Choi YB, White-Grindley E, Majumdar A, Kandel ER. Aplysia CPEB Can Form Prion-like Multimers in Sensory Neurons that Contribute to Long-Term Facilitation. Cell. 2010;140:421–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou F, et al. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell. 2011;146:448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olzscha H, et al. Amyloid-like aggregates sequester numerous metastable proteins with essential cellular functions. Cell. 2011;144:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hart lM. Nature. 2011;475:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young JC. Mechanisms of the Hsp70 chaperone system. Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;88:291–300. doi: 10.1139/o09-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma SK, De los Rios P, Christen P, Lustig A, Goloubinoff P. The kinetic parameters and energy cost of the Hsp70 chaperone as a polypeptide unfoldase. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:914–920. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dragovic Z, Broadley SA, Shomura Y, Bracher A, Hartl FU. EMBO J. 2006;25:2519–2528. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raviol H, Sadlish H, Rodriguez F, Mayer MP, Bukau B. EMBO J. 2006;25:2510–2518. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polier S, Dragovic Z, Hartl FU, Bracher A. Cell. 2008;133:1068–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuermann JP, et al. Mol Cell. 2008;31:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goeckeler JL, et al. The yeast Hsp110, Sse1p, exhibits high-affinity peptide binding. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2393–2396. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q, Hendrickson WA. Insights into Hsp70 chaperone activity from a crystal structure of the yeast Hsp110 Sse1. Cell. 2007;131:106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polier S, Hartl FU, Bracher A. Interaction of the Hsp110 molecular chaperones from S. cerevisiae with substrate protein. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:696–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang S, Binari R, Zhou R, Perrimon N. A genomewide RNA interference screen for modifiers of aggregates formation by mutant Huntingtin in Drosophila. Genetics. 2010;184:1165–1179. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.112516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muralidharan V, Oksman A, Iwamoto M, Wandless TJ, Goldberg DE. Asparagine repeat function in a Plasmodium falciparum protein assessed via a regulatable fluorescent affinity tag. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4411–4416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018449108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DePace AH, Santoso A, Hillner P, Weissman JS. A critical role for amino-terminal glutamine/asparagine repeats in the formation and propagation of a yeast prion. Cell. 1998;93:1241–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaner NC, et al. Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2008;5:545–551. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duraisingh MT, Triglia T, Cowman AF. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruz AK, Titus R, Beverley SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1599–1603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong CM, Goldberg DE. An FKBP destabilization domain modulates protein levels in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Methods. 2007;4:1007–1009. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dvorin JD, et al. A Plant-Like Kinase in Plasmodium falciparum Regulates Parasite Egress from Erythrocytes. Science. 2010;328:910–912. doi: 10.1126/science.1188191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo I, Oksman A, Vaupel B, Goldberg DE. A calpain unique to alveolates is essential in Plasmodium falciparum and its knockdown reveals an involvement in pre-S-phase development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1554–1559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806926106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halfmann R, Lindquist S. J Vis Exp. 2008;17:e838. doi: 10.3791/838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kryndushkin DS, Alexandrov IM, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Kushnirov VV. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49636–49643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groenning M. J Chem Biol. 2009;3:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12154-009-0027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alavez S, Vantipalli MC, Zucker DJS, Klang IM, Lithgow GJ. Nature. 2011;472:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi: 10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klemba M, Beatty W, Gluzman I, Goldberg DE. Trafficking of plasmepsin II to the food vacuole of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:47–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb200307147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganesan SM, et al. Yeast dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a new selectable marker for Plasmodium falciparum transfection. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011;177:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drew ME, et al. Plasmodium food vacuole plasmepsins are activated by falcipains. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12870–12876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708949200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo I, Oksman A, Goldberg DE. Fatty acid acylation regulates trafficking of the unusual Plasmodium falciparum calpain to the nucleolus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:229–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Gluzman IY, Drew ME, Goldberg DE. The role of Plasmodium falciparum food vacuole plasmepsins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1432–1437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mamoun CB, Goldberg DE. Plasmodium protein phosphatase 2C dephosphorylates translation elongation factor 1beta and inhibits its PKC-mediated nucleotide exchange activity in vitro. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:973–981. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.