Abstract

Background

Until date, there are no clear recommendations for regular perioperative measurements of serum CEA levels for lung cancer in any guidelines. The purpose in the present study is to evaluate the prognostic significance of perioperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in patients with pathological-stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 263 completely resected pathological-stage I NSCLC patients whose preoperative and postoperative serum CEA levels were measured. Patients were subdivided according to the perioperative change of CEA levels: continuously normal CEA levels (NN group), continuously high CEA levels (HH group), and high preoperative CEA levels that returned to normal levels post-operation (HN group). The clinicopathological factors and overall survival (OS) among these 3 groups were compared. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the correlation between clinicopathological factors and OS were performed.

Results

High preoperative CEA levels significantly correlated with men aged >70 years with smoking history, high serum CYFRA 21–1 levels, greater tumor diameter, presence of visceral pleural invasion (VPI), and moderate-to-poor differentiation. Five-year OS rates in the NN and HH groups were 95.5% and 59.3%, respectively. Four-year OS rate in the HN group was 85.5%. Multivariate analyses indicated tumor diameter of more than 30 mm, presence of VPI, and the HH group were independent unfavorable prognostic factors.

Conclusions

A high postoperative CEA level was an independent unfavorable prognostic factor in pathological-stage I NSCLC patients. Patients with high postoperative CEA levels may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Unfavorable prognostic factor, Pathological-stage I, Postoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level, Adjuvant chemotherapy

Background

In many clinical practices, serum tumor markers are easily and reproducibly evaluated. Measurement of tumor markers in patients with malignancies enables us to diagnose, quantitatively assess cancer cells, predict survival, and monitor the effects of treatment.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is one of the most commonly used tumor markers in gastrointestinal and lung cancers. Many reports have already described the significant correlation of preoperative CEA levels with prognosis in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [1-7]. However, serum CEA levels are known to be affected by the rate of CEA elimination from circulating blood determined by renal function and smoking status [8].

From this perspective, postoperative CEA levels might be a more accurate prognostic factor than preoperative CEA levels, because the former is less affected by preoperative smoking status. Dent et al. initially reported high values of postoperative CEA levels [9]. Subsequent reports demonstrated that high postoperative CEA levels predicted recurrence and prognosis in NSCLC patients [4,8,10-15]. Until date, however, there are no clear recommendations for regular perioperative measurements of serum CEA levels for lung cancer in any guidelines.

We conducted a retrospective study based on a single institution to evaluate the prognostic importance of perioperative serum CEA levels in patients with completely resected pathological-stage I NSCLC.

Methods

Between September 2002 and December 2009, 545 patients underwent complete surgical resection for pathological-stage I NSCLC at the Shizuoka Cancer Center Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan. Of these, 263 consecutive patients who met all of the following criteria were included and retrospectively reviewed in the present study: (1) those who had their serum CEA concentrations measured within the 1-month period before surgery and again within the 2-month period after surgery (while preoperative serum CEA levels were measured routinely, the measurement of postoperative CEA levels was at the discretion of the attending surgeon), (2) those without multiple lung tumors or malignancies in other organs and (3) those who were anticancer treatment-naïve in both the neoadjuvant setting and adjuvant setting. Approval from the institutional ethics committee was obtained.

The medical records of each patient were examined for age, gender, smoking history, preoperative European Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), both preoperative and postoperative serum CEA levels, preoperative serum cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) levels, tumor location, surgical procedure, tumor histology, tumor diameter, visceral pleural invasion (VPI), angiolymphatic invasion (ALI), differentiation grade, and survival. Staging was determined according to the seventh edition of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM staging system [16]. Histology was evaluated according to the latest World Health Organization’s classification of lung tumors [17].

We performed lobectomy or pneumonectomy with systemic mediastinal lymph node dissection as the standard surgical treatment. Segmentectomy or wedge resection was performed only on patients with tumors showing a greater proportion of ground-glass opacity on computed tomography or on those with major comorbidities.

Serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations were measured within the 1-month period before surgery (at the same time as CEA). The CEA concentration was measured using an ARCHITECT(r) kit (Abbott Japan, Tokyo, Japan), while the CYFRA21-1 concentration was measured using an Lumipulse Presto(r) kit (FUJIREBIO Inc, Tokyo, Japan). According to the manufacturer of these kits, the upper limits of the percentiles of healthy individuals for CEA and CYFRA21-1 levels were 5.0 ng/mL and 3.5 ng/mL, respectively. Therefore, the cut-off point for these tumor markers was set to the same level as the upper limits in the present study. Patients were subdivided into 3 groups on the basis of their shift of CEA levels by surgery as follows: patients with continuously normal CEA levels (NN group), patients with continuously high CEA levels (HH group), and patients with high preoperative CEA levels that returned to normal levels post-operation (HN group).

ALI was defined as the presence of neoplastic cells within an arterial, venous, or lymphatic lumen during routine histologic evaluation with hematoxylin and eosin, elastic van Gieson (EVG), and D2-40 stains. Because of the retrospective nature of this study, distinction between arterial, venous, or lymphatic invasion were not available in some cases. Therefore, these categories were merged into a single variable (ALI). The presence or absence of ALI was assessed in the largest cross-sections of the tumor in every specimen. VPI was defined as evidence of penetration of the thick outer elastic lamina by the tumor during EVG staining. The grade of differentiation was categorized into well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated carcinomas according to the degree of structural and cytologic atypia. Differentiation in squamous cell carcinoma was determined on the basis of the degree of keratinization and the presence of intercellular bridges. Poor differentiation in squamous cell carcinoma was defined as a tumor with faint these features and a solid pattern. Adenocarcinoma, which is largely composed of malignant glandular epithelium, was evaluated by lepidic, tubular and papillary structure. Poor differentiation in adenocarcinoma was defined as a solid pattern tumor without any clear gland formation. Pathological evaluation was performed prospectively by 2 or more experienced pathologists.

The clinicopathological factors of the patients (n = 263) are listed in Table 1. There were 132 men and 131 women, with a median age at surgery of 67 years (range, 20–88 years). There were 198, 44, and 21 patients in the NN, HN, and HH groups, respectively. Pathological examinations revealed that there were 213 adenocarcinomas, 46 squamous cell carcinomas, 2 adenosquamous carcinomas, and 2 carcinoids.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological factors of the total study population

| Factors |

Total |

NN group |

HN group |

HH group |

p value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 263) | (n = 198) | (n = 44) | (n = 21) | ||

| Age |

|

|

|

|

0.010 |

| ≤70 y |

140 |

116 |

16 |

8 |

|

| >70 y |

123 |

82 |

28 |

13 |

|

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

0.002 |

| Male |

132 |

87 |

30 |

15 |

|

| Female |

131 |

111 |

14 |

6 |

|

| Smoking history |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

| ≥5 PY |

135 |

85 |

33 |

17 |

|

| <5 PY |

128 |

113 |

11 |

4 |

|

| ECOG PS |

|

|

|

|

0.28 |

| 0 |

222 |

169 |

38 |

15 |

|

| 1 |

41 |

29 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Serum CYFRA |

|

|

|

|

0.039 |

| >3.5 ng/mL |

12 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

|

| ≤3.5 ng/mL |

251 |

193 |

39 |

19 |

|

| Location |

|

|

|

|

0.77 |

| Right |

167 |

124 |

30 |

13 |

|

| Left |

96 |

74 |

14 |

8 |

|

| Surgical procedure |

|

|

|

|

0.98 |

| Sublobar resection |

38 |

29 |

6 |

3 |

|

| Major resection b |

225 |

169 |

38 |

18 |

|

| Tumor diameter |

|

|

|

|

0.002 |

| >30 mm |

53 |

30 |

17 |

6 |

|

| ≤30 mm |

210 |

168 |

27 |

15 |

|

| Histology |

|

|

|

|

0.27 |

| Adeno |

213 |

165 |

33 |

15 |

|

| Squamous |

46 |

30 |

11 |

5 |

|

| Others |

4 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

|

| VPI |

|

|

|

|

0.037 |

| Present |

50 |

31 |

11 |

8 |

|

| Absent |

213 |

167 |

33 |

13 |

|

| ALI |

|

|

|

|

0.32 |

| Present |

66 |

49 |

9 |

8 |

|

| Absent |

197 |

149 |

35 |

13 |

|

| Differentiation c |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

| Well |

168 |

140 |

19 |

9 |

|

| Moderate/Poor | 91 | 55 | 25 | 11 |

PY, Pack-years; ECOG PS, European cooperative oncology group performance status; CYFRA, Cytokeratin 19 fragment; VPI, Visceral pleural invasion; ALI, Angiolymphatic invasion.

aassociation between the NN group and HN group, the chi-square test.

b Major resection refers to lobectomy or pneumonectomy.

c The grade of differentiation was not determined in 4 patients with adenosquamous carcinoma or carcinoids.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the period from surgical resection until death or the date of the last follow-up evaluation. Last actualization of survival data was performed in September 2012. Follow-up was completed in 245 of the patients. The median time for follow-up for surviving patients was 54 months (range, 15–120 months). Of the total, 22 patients (8.4%) died during follow-up. The causes of death were primary disease in 21 patients and comorbid diseases in 1.

Statistical analysis

Counts were compared using the chi-square test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate survival curves, and survival differences were analyzed using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. A p- value of less than 5% was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients’ clinicopathological factors according to the CEA group

The HN group significantly correlated to older men (>70 y) with a smoking history (≥5 pack-years), high serum CYFRA 21–1 levels (>3.5 ng/mL), greater tumor diameter (>30 mm), presence of VPI, and moderate-to-poor differentiation compared to the NN group (Table 1).

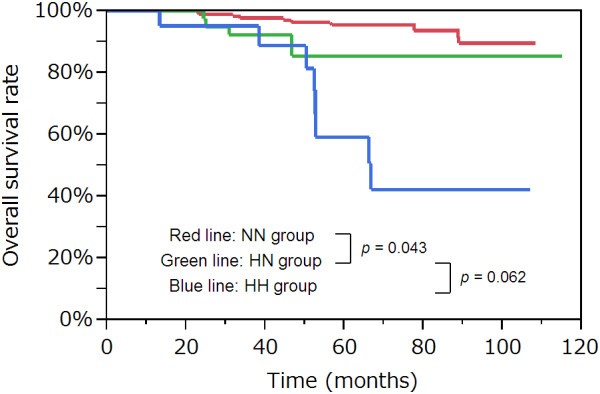

OS curves according to the CEA group

Five-year OS rates in the NN and HH groups were 95.5% and 59.3%, respectively. Four-year OS rate in the HN group was 85.5%. A significant difference in OS was observed between the HN and NN groups (p = 0.043). A trend toward a decreased survival was observed for the HH group compared to the HN group, but was not statistically significant (p = 0.062). These survival curves are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall survival curves according to the CEA group. A significant difference in overall survival was observed between the HN group and NN group (p = 0.043). There was a marginally significant difference in overall survival between the HH group and HN group (p = 0.062). CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Predictors of OS according to univariate analyses

The results of univariate analyses for survival are summarized in Table 2. The clinicopathological factors of age, ECOG PS, serum CEA levels, tumor diameter, VPI, ALI, and differentiation grade were significant prognostic factors for OS.

Table 2.

Predictors of OS according to univariate analysis

| Risk factors | Favorable | Unfavorable | p Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

≤70 y |

>70 y |

0.008 |

| Gender |

Female |

Male |

0.12 |

| Smoking history |

<5 PY |

≥5 PY |

0.088 |

| ECOG PS |

0 |

1 |

0.007 |

| Serum CEA |

NN group |

HN group |

0.043 |

| HN group |

HH group |

0.062 |

|

| Serum CYFRA |

≤3.5 ng/mL |

>3.5 ng/mL |

0.90 |

| Location |

Left |

Right |

0.99 |

| Surgical procedure |

Major resection b |

Sublobar resection |

0.57 |

| Tumor diameter |

≤30 mm |

>30 mm |

< 0.001 |

| Histology |

Adeno |

Others |

0.070 |

| VPI |

Absent |

Present |

0.001 |

| ALI |

Absent |

Present |

0.008 |

| Differentiation | Well | Moderate/Poor | 0.037 |

OS, Overall survival; PY, Pack-years; ECOG PS, European cooperative oncology group performance status; CEA, Carcinoembryonic antigen; CYFRA, Cytokeratin 19 fragment level; VPI, Visceral pleural invasion; ALI, Angiolymphatic invasion.

a the log-rank test.

b Major resection refers to lobectomy or pneumonectomy.

Predictors of OS according to multivariate analyses

Multivariate analyses for OS were performed using these factors, and the results are summarized in Table 3. Tumor diameter of more than 30 mm (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.47, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.35–8.98, p = 0.010), presence of VPI (HR = 3.18, 95% CI: 1.11–8.84, p = 0.032), and the HH group (HR = 7.69, 95% CI: 2.46–23.7, p < 0.001) were found to be independent unfavorable prognostic factors.

Table 3.

Predictors of OS according to multivariate analysis

| Risk factors | HR | 95% CI | p value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

|

|

|

| ≤70 y |

1 |

Reference |

|

| >70 y |

2.29 |

0.87–6.72 |

0.095 |

| ECOG PS |

|

|

|

| 0 |

1 |

Reference |

|

| 1 |

1.33 |

0.47–3.53 |

0.59 |

| Tumor diameter |

|

|

|

| ≤30 mm |

1 |

Reference |

|

| >30 mm |

3.47 |

1.35–8.98 |

0.010 |

| VPI |

|

|

|

| Absent |

1 |

Reference |

|

| Present |

3.18 |

1.11–8.84 |

0.032 |

| ALI |

|

|

|

| Absent |

1 |

Reference |

|

| Present |

1.06 |

0.38–3.15 |

0.91 |

| Differentiation |

|

|

|

| Well |

1 |

Reference |

|

| Moderate/Poor |

1.14 |

0.42–3.01 |

0.80 |

| Serum CEA |

|

|

|

| NN group |

1 |

Reference |

|

| HN group |

2.52 |

0.72–8.11 |

0.14 |

| HH group | 7.69 | 2.46–23.7 | < 0.001 |

OS, Overall survival; HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval; ECOG PS, European cooperative oncology group performance status; VPI, Visceral pleural invasion; ALI, Angiolymphatic invasion; CEA, Carcinoembryonic antigen.

a the log-rank test.

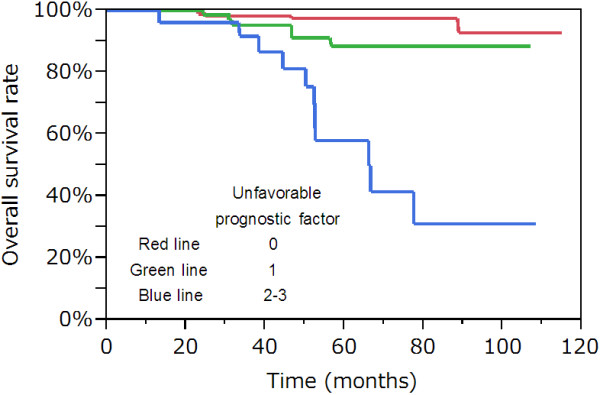

OS curves according to the number of unfavorable prognostic factors

Figure 2 shows OS curves according to the number of independent unfavorable prognostic factors (tumor diameter of more than 30 mm, presence of VPI, and the HH group) on the basis of the results of multivariate analyses. Five-year OS rate was 58.0% for those harboring 2 or more unfavorable prognostic factors (n = 25).

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves according to the number of independent unfavorable prognostic factors (tumor diameter of more than 30 mm, presence of VPI, and the HH group) on the basis of the results of multivariate analyses. Five-year overall survival rate was 58.0% for those harboring 2 or more unfavorable prognostic factors (n = 25). VPI, visceral pleural invasion.

Discussion

There have been 3 reports published, which were similar in design to the present study [4,11,15] and subdivided pathological-stage I NSCLC patients into 3 groups, viz. the NN, HN, and HH groups (Table 4). These previous reports have demonstrated that the worst prognosis correlates to the HH group, consistent with results of the present study. Taken together, these results suggest that failure to normalize CEA levels after surgery is associated with a significantly worse prognosis. Okada et al. speculated that failure to achieve normal levels of CEA levels is caused either by unrecognized extrapulmonary disease or failure to eradicate all pulmonary diseases [4]. The results in the current study show that the 5-year OS rate in the HH group was 59.3%, the highest compared to those in previous reports (range, 36.0%–48.6%). A similar trend was observed among the HN and NN groups as well. The previous reports included incomplete resections [4] and higher percentages of pathological-stage IB patients (60.3% vs. 33.0% compared with the present study) [15], and these differences could be the possible reason for decreased survival.

Table 4.

Comparison of the previous reports analyzing the perioperative change of serum CEA levels in patients with pathological stage-I NSCLC

| Author | Okada [4] | Matsuguma [11] | Wang [15] | Present study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year |

2004 |

2008 |

2010 |

2013 |

|||

| CEA measurement period |

Before surgery |

Within 1 M |

Within 1 M |

Within 2 W |

Within 1 M |

||

| After surgery |

Within 1 M |

Within 1–3 M |

Within 1–3 M |

Within 2 M |

|||

| Cut-off point (ng/mL) |

5.0 |

5.0 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

|||

| Total number |

722 a |

455 |

257 |

263 |

|||

| NN group |

(5-ys) |

472 (84.2%) |

323 (85.9%) |

173 (71.1%) |

198 (95.5%) |

||

| HN group |

154 (74.2%) |

112 (56.2%) |

56 (54.6%) |

44 (85.5%) b |

|||

| HH group |

96 (48.6%) |

20 (43.1%) |

28 (36.0%) |

21 (59.3%) |

|||

| Independent prognostic factor | N/A | Age |

Age |

Tumor diameter |

|||

| Histology |

HH group |

VPI |

|||||

| VPI |

|

HH group |

|||||

| HN/HH group | |||||||

CEA, Carcinoembryonal antigen; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; M, Month; W, Week; N/A, Not analyzed; VPI, Visceral pleural invasion.

a including incomplete resections.

b 4-ys.

Matsuguma et al. reported that preoperative high CEA levels significantly correlated with smoking-related factors such as increased age, male gender, squamous cell carcinoma, pathological T2 status, vascular invasion, VPI, and moderate-to-poor differentiation (only in adenocarcinomas) [11]. These observations are mostly consistent with those reported in the present study. Wang et al. reported that histologic adenocarcinomas significantly correlated with high preoperative CEA levels, whereas age, smoking status, tumor diameter, VPI, and pathological-stage did not [15]. One of the most notable differences between the current study and previous reports is that we did not observe any significant correlation between CEA levels and histologic type. Although CEA was initially investigated in colon adenocarcinoma, it has been known to be elevated in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, uterine cervix, and esophagus [18-22]. The correlation of CEA levels and histologic subtype of NSCLC remained still controversial.

Our results indicate that tumor diameter of more than 30 mm, presence of VPI, and the HH group were independent unfavorable prognostic factors. The former 2 factors are the most representative determinants for lung cancers to be categorized as T2a according to the seventh edition of the UICC TNM staging system [16]. Since T2aN0M0 lung cancers are staged as pathological-stage IB, our results confirmed the prognostic value of pathological-stage classification, which is the most widely-used prognosticator in lung cancer.

We also highlighted the prognostic significance of continuously high perioperative CEA levels (HH group), consistent with the results by Wang et al. [15]. Because all of the patients with postoperative high CEA levels had preoperative high CEA levels as well, the results indicate the need for measuring postoperative CEA levels rather than preoperative CEA levels. On the other hand, Matsuguma et al. reported that both HN and HH groups were independent unfavorable prognostic factors [11], indicating the need for measuring preoperative CEA levels. In the Western countries, however, regular perioperative measurement of serum CEA levels in patients with lung cancer is not commonly performed and is considered less convincing than in patients with colorectal cancer [4,23].

In Japan, adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT is recommended in pathological-stage IB NSCLC patients because the occurrence of postoperative death was found to have decreased in the UFT group as compared to the control group in previous studies [24,25]. As mentioned earlier, our results indicate the prognostic significance of discriminating pathological-stage IB from IA, supporting this recommendation. The most important clinical implications emerging from this study is that patients with postoperative high CEA levels are also good candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to pathological-stage IB patients. Although in-anatomical factors of tumor markers are not reflected in the current TNM staging system, the results of our study indicate that postoperative high CEA levels can predict survival, representing micrometastases or residual tumor cells, which may not be detected by radiological images and pathological examination.

Independent prognostic significance of postoperative high CEA levels is yet to be proved in advanced NSCLC patients. Sawabata et al. speculated that this might be attributable to the stronger prognostic impact of anatomic factors such as lymph node metastases than tumor markers [13]. On the other hand, Fukai et al. reported that an elevated preoperative CEA levels (≥5 ng/mL) was an independent predictor of survival even in pT1-2N1M0 NSCLC patients [26]. These studies therefore suggest that the prognostic significance of high postoperative CEA levels should also be validated in advanced NSCLC patients.

The present study has several limitations: First is its retrospective nature; second, postoperative CEA levels were measured at the discretion of the attending surgeon, adding significant selective bias into the present study; third, there was a small sample size of the HH group (n = 21) and observed events, making it statistically difficult to interpret results.

Conclusions

A high postoperative CEA level was an independent unfavorable prognostic factor in completely resected pathological-stage I NSCLC patients. Those with postoperative high CEA levels may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Abbreviations

CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer; ECOG PS: European cooperative oncology group performance status; CYFRA21-1: Cytokeratin 19 fragment; OS: Overall survival; VPI: Visceral pleural invasion; ALI: Angiolymphatic invasion; UICC: International union against cancer; EVG: Elastic van Gieson.

Competing interests

This work was supported by the National Cancer Research and Development Fund (23-A-18).

Authors’ contributions

TM conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. ST and MI both advised and interpreted of data. YO and TN participated in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yoshiki Kozu, Email: y.kozu@scchr.jp.

Tomohiro Maniwa, Email: t.maniwa@scchr.jp.

Shoji Takahashi, Email: s.takahashi@scchr.jp.

Mitsuhiro Isaka, Email: m.isaka@scchr.jp.

Yasuhisa Ohde, Email: y.ode@scchr.jp.

Takashi Nakajima, Email: t.nakajima@scchr.jp.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ichiro Ito, Division of Pathology, Shizuoka Cancer Center, Shizuoka, Japan, for his critical review of the manuscript.

Mitsuru Takahashi, the Chairman of the Ethics Committee, approved this study.

References

- Inoue M, Minami M, Shiono H, Sawabata N, Ideguchi K, Okumura M. Clinicopathologic study of resected, peripheral, small-sized, non-small cell lung cancer tumors of 2 cm or less in diameter: pleural invasion and increase of serum carcinoembryonic antigen level as predictors of nodal involvement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:988–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K, Sumitomo S, Nakashima N, Nakajima D, Misaki N. Prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA21-1 in patients with pathological stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muley T, Dienemann H, Ebert W. CYFRA 21–1 and CEA are independent prognostic factors in 153 operated stage I NSCLC patients. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1953–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, Uchino K, Yuki T, Nakagawa A, Tsubota N. Prognostic significance of perioperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen in non-small cell lung cancer: analysis of 1,000 consecutive resections for clinical stage I disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakao Y, Tomimitsu S, Takeda Y, Natsuaki M, Itoh T. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a predictive factor for postoperative tumor relapse in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:520–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawabata N, Ohta M, Takeda S, Hirano H, Okumura Y, Asada H, Maeda H. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen level in surgically resected clinical stage I patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:174–179. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Moriyama E, Nishimura M, Takahashi K, Nishiwaki Y. Prognostic factors in clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:927–932. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)00140-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimasu T, Kokawa Y, Oura S, Hirai I, Sasaki R, Tanino H, Sakurai T, Okamura Y. Time course of carcinoembryonic antigen after resection of lung cancer: a predictor of recurrence. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:741–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent PB, McCulloch PB, Wesley-James O, MacLaren R, Muirhead W, Dunnett CW. Measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer. 1978;42:1484–1491. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197809)42:3+<1484::AID-CNCR2820420819>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwabara K, Saeki S, Sasaki J, Nomura M, Kohrogi H. Combined evaluation of postoperative serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen less than or equal to 2.5 ng/ml and absence of vascular invasion may predict no recurrence of stage I adenocarcinoma lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1416–1420. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818dda85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuguma H, Nakahara R, Igarashi S, Ishikawa Y, Suzuki H, Miyazawa N, Honjo S, Yokoi K. Pathologic stage I non-small cell lung cancer with high levels of preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen: clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka M, Kataoka D, Yamamoto S, Bito A, Matsuoka J, Kawada T, Takaba T. Pre- and post-operative serum carcinoembryonic antigen in primary lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;10:281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawabata N, Maeda H, Yokota S, Takeda S, Koma M, Tokunaga T, Ito M. Postoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels in patients with pathologic stage IA nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: subnormal levels as an indicator of favorable prognosis. Cancer. 2004;101:803–809. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita M, Matsuzaki Y, Shimizu T, Hara M, Ayabe T, Onitsuka T. Prognostic determinants for lung cancer patients with preoperative high serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;53:300–304. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Huang MS, Huang MH, Lee HC, Hsu HS. Persistently high serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels after surgery indicate poor prognosis in patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Surg Res. 2010;163:e45–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, Postmus PE, Rusch V, Sobin L. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis WD BE, HK M-H, Harris CC. World Health Organization classification of tumors: pathology and genetics of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SN, Namkoong SE, Jung JK, Kim CJ, Park JS, Kim JW, Lee JM, Kim SJ. Prognostic significance of pretreatment squamous cell carcinoma antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:418–424. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Nishimaki T, Kanda T, Nakagawa S, Ohashi M, Hatakeyama K. Clinical significance of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19–9, and squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels in esophageal cancer patients. World J Surg. 2004;28:680–685. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-6865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SW, Liang JA, Hung YC, Yeh LS, Chang WC, Yang SN, Lin FJ. Clinical implications of elevated pretreatment carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Tumour Biol. 2008;29:255–261. doi: 10.1159/000152943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima T, Sakao Y, Mun M, Ishikawa Y, Nakagawa K, Masuda M, Okumura S. A Clinicopathological Study of Resected Small-Sized Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Peripheral Lung: Prognostic Significance of Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shimada H, Nabeya Y, Okazumi S, Matsubara H, Shiratori T, Gunji Y, Kobayashi S, Hayashi H, Ochiai T. Prediction of survival with squamous cell carcinoma antigen in patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 2003;133:486–494. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccheri G, Ferrigno D. Identifying patients at risk of early postoperative recurrence of lung cancer: a new use of the old CEA test. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:973–980. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada C, Tanaka F, Ohta M, Fujimura S, Kodama K, Imaizumi M, Wada H. Meta-analysis of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with tegafur-uracil in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4999–5006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Ichinose Y, Ohta M, Hata E, Tsubota N, Tada H, Watanabe Y, Wada H, Tsuboi M, Hamajima N. A randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil-tegafur for adenocarcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1713–1721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukai R, Sakao Y, Sakuraba M, Oh S, Shiomi K, Sonobe S, Saitoh Y, Miyamoto H. The prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in T1N1M0 and T2N1M0 non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]