Abstract

Background and purpose

Total elbow replacement (TER) is used in the treatment of inflammatory arthropathy, osteoarthritis, and posttraumatic arthrosis, or as the primary management for distal humeral fractures. We determined the annual incidence of TER over an 18-year period. We also examined the effect of surgeon volume on implant survivorship and the rate of systemic and joint-specific complications.

Methodology

We examined a national arthroplasty register and used linkage with national hospital episode statistics, and population and mortality data to determine the incidence of complications and implant survivorship.

Results

There were 1,146 primary TER procedures (incidence: 1.4 per 105 population per year). The peak incidence was seen in the eighth decade and TER was most often performed in females (F:M ratio = 2.9:1). The primary indications for surgery were inflammatory arthropathy (79%), osteoarthritis (9%), and trauma (12%). The incidence of TER fell over the period (r = –0.49; p = 0.037). This may be due to a fall in the number of procedures performed for inflammatory arthropathy (p < 0.001). The overall 10-year survivorship was 90%. Implant survival was better if the surgeon performed more than 10 cases per year.

Interpretation

The prevalence of TER has fallen over 18 years, and implant survival rates are better in surgeons who perform more than 10 cases per year. A strong argument can be made for a managed clinic network for total elbow arthroplasty.

Total elbow replacement (TER) is used in the treatment of inflammatory arthropathy, osteoarthritis, and posttraumatic arthrosis, or as the primary management for distal humeral fractures. The majority of TERs are performed for the management of rheumatoid elbows (Ehrlich 2001). However, over the last 20 years, the natural history of inflammatory elbow arthropathy has changed. This may be a result of both an improvement in the general health of the population and the introduction of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and this is likely to have influenced the rate of elbow arthroplasty (Shourt et al. 2012).

We examined the annual incidence of TER in a defined population, paying particular attention to change over time. We also examined the effect of surgeon volume on implant survivorship and the rate of systemic and joint-specific complications.

Methods

Data collection

Patients undergoing a total elbow arthroplasty or revision arthroplasty from January 1991 to December 2008 were identified using the national SMR01 (Scottish Morbidity Record) records. This was performed in conjunction with the Scottish Arthroplasty Project, which is administered by the Information Services Division (ISD) of the NHS (National Health Service) Services Scotland, and aims to encourage improved quality of care provided to patients undergoing joint replacement throughout Scotland. This methodology has allowed us to identify subsequent complications and revisions, even at different institutions from that of the primary procedure.

Each in-patient hospital episode in Scotland generates an SMR01 record. The national arthroplasty dataset is derived from SMR01 and NRS (National Records of Scotland) death records, and holds information on all arthroplasty operations performed from 1982, for patients aged 16 and over, as well as associated complications, re-admissions, and deaths. Every quarter, the data are validated further by sending each surgeon in Scotland a report of his/her operations to confirm the procedure and diagnosis. Procedures are recorded using the OPCS-4 (Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures) clinical coding system while diagnoses are recorded using the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) coding system versions 9 and 10. The coding is performed by trained clinical coders and regular quality-assurance audits of the coding are undertaken. Coding of procedures has been validated, with a data accuracy of 93% reported (NHS National Services Scotland 2007). Data linkage was used to identify episodes of thromboembolism, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and death within one year. Any episodes of septic arthritis, dislocation, or periprosthetic fracture during the study period were recorded. The length of stay and operating surgeon, and any other arthroplasty episodes during the study period were identified. The primary diagnosis was determined as being either inflammatory arthropathy, osteoarthritis, or trauma using the ICD codes.

Statistics

Kaplan-Meier survivorship methodology was used to report the cumulative prevalence of implant failure, defined as revision TER, and complications in those who underwent primary TER during the study period. Patients were censored at the point of death or at the end of the study period. The log-rank test was used to identify differences in survival between groups. Population estimates from the National Records for Scotland were used to calculate the prevalence (General Registrar Office for Scotland). Means (with SD) are reported for continuous parametric data and medians for non-parametric data. Chi-squared tests were performed to compare the prevalence between categorical variables. 2-tailed p-values are reported along with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the ratio. Linear regression was used to examine the number of total elbow replacements performed vs. time. The coefficient of time is reported along with the r2 value for the regression equation. There were no simultaneous bilateral cases performed. If a patient had a subsequent contralateral elbow arthroplasty, it was not considered in this analysis, and only the survivorship of their first implant was reported.

Results

1,146 patients underwent TER during the study period. Of these, 190 patients underwent a second, contralateral staged TER. Thus, the study group comprised 1,146 first, primary TER procedures performed over the 18-year period. The overall incidence of primary TER was 1.4 per 105 population per year. Mean age at the time of primary operation was 61 years (18–94). The greatest incidence of TER was in the 70- to 79-year-old age group (4.9 per 105) and the lowest incidence was in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (0.05 per 105). The incidence in females was 2.0 per 105 (n = 853) as compared to 0.8 per 105 (n = 293) in males (F:M ratio = 2.9:1, OR = 2.7, CI: 2.4–3.1; p < 0.001). 908 TER procedures (78%) were undertaken for inflammatory arthropathy, 108 (8%) were undertaken for osteoarthritis, and 74 (12%) were undertaken for trauma. We were unable to determine the underlying diagnosis in 56 patients.

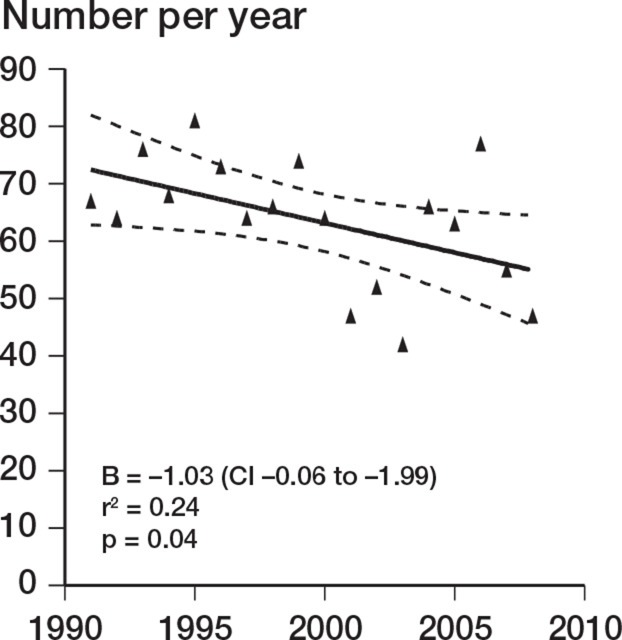

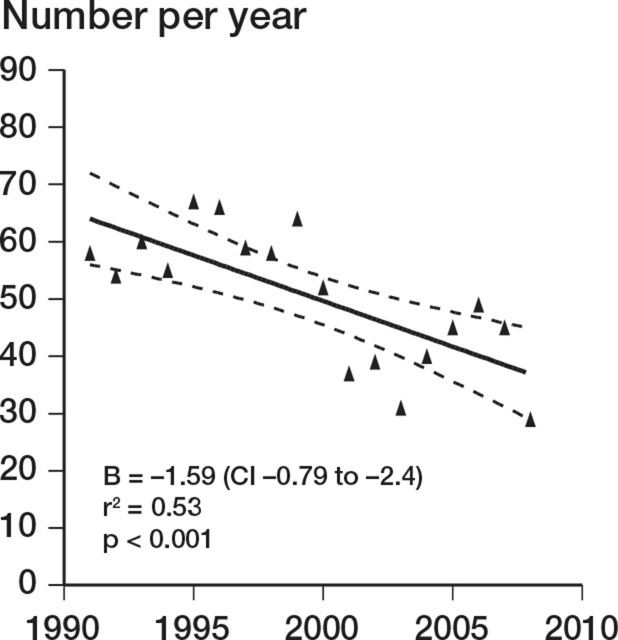

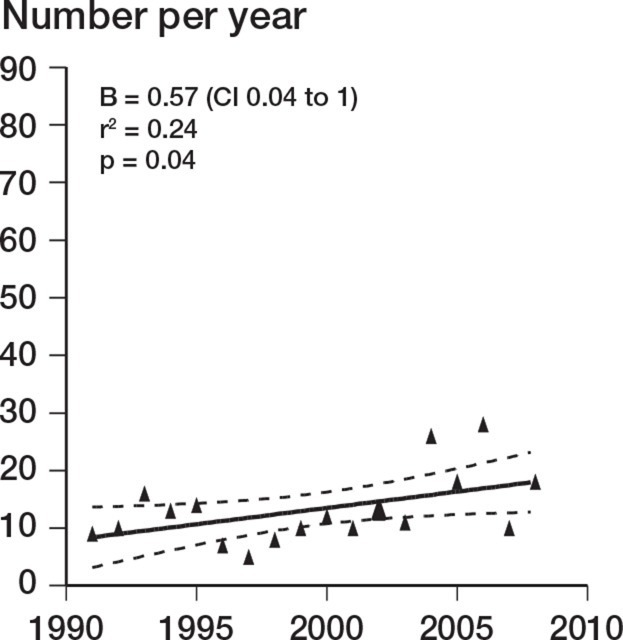

There was a decrease in the number of TERs performed during the study period (r = –0.49; p = 0.04). This was accounted for by a decrease over the study period in TER performed for inflammatory arthropathy (r = –0.73; p < 0.001). TER for noninflammatory causes increased over the same period (r = 0.49; p = 0.04) (Figures 1–3). There was no change in the incidence of revision TER over time (p = 0.5), which was 0.23 per 105 overall.

Figure 1.

Annual number of TERs over time.

Figure 2.

Change in incidence over time for TERs carried out for rheumatoid arthritis.

Figure 3.

Change in prevalence versus time for TER performed for non-inflammatory conditions

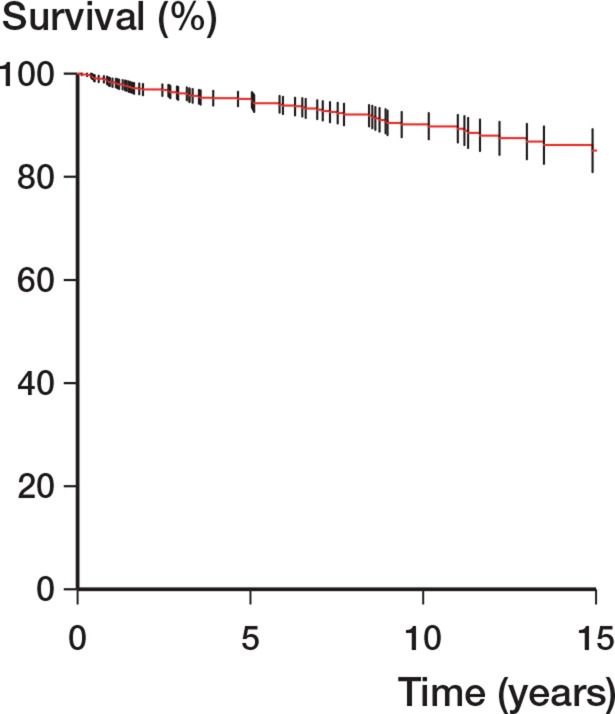

The procedures were carried out by 51 surgeons, 27 of whom performed up to 4 procedures, 6 of whom carried out between 5 and 9 procedures, and 18 of whom carried out more than 10. Only 2 surgeons had an average annual volume of more than ten procedures a year. The Kaplan-Meier survivorship was 90.2% at 10 years and it was 85.1% at 18 years (Table 1 and Figure 4). The best survivorship was seen in patients in whom the TER was undertaken by the 2 surgeons who performed 10 or more procedures a year (p = 0.02) (Table 1). Neither the indication for TER (p = 0.09) nor age (p = 0.3) influenced survivorship.

Table 1.

Implant survivorship (Kaplan-Meier) with revision as endpoint, by number of procedures per surgeon per year, diagnosis, and age

| Implant survivorship (%) (endpoint: revision) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 years | 18 years | p-valuea | |

| Overall | 90 (88–93) | 85 (81–89) | ||

| Average no. of procedures per surgeon per year | ||||

| 0–4 | 412 | 90 (86–94) | 83 (75–91) | 0.02 |

| 5–9 | 296 | 85 (79–91) | 82 (73–90) | |

| ≥ 10 | 319 | 94 (91–97) | 89 (84–95) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Inflammatory | 738 | 90 (87–93) | 84 (78–89) | 0.09 |

| Osteoarthritis | 95 | 85 (74–95) | 85 (74–95) | |

| Trauma | 142 | 98 (96–100) | 98 (96–100) | |

| Unknown | 48 | 87 (76–98) | 87 (76–98) | |

| Age | ||||

| 16–54 | 260 | 90 (85–94) | 81 (73–89) | 0.3 |

| 55–74 | 591 | 90 (86–93) | 87 (83–92) | |

| > 74 | 176 | 96 (93–99) | 96 (93–99) | |

a for log-rank test from Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Figure 4.

Overall Kaplan-Meier survivorship with revision as endpoint. Bars represent CI.

The1-year mortality rate was 1.2% (Table 2). The 10-year Kaplan-Meier cumulative complication rate for infection was 11%, and it was 0.9% for dislocation and 1.3% for periprosthetic fracture. There were no statistically significant differences in dislocation rate (p = 0.20), infection rate (p = 0.7), or periprosthetic fracture rate (p = 0.9) between surgeons undertaking higher volumes of surgery and those performing fewer procedures (Table 3). There were significant differences (p = 0.01) in the case-mix between surgeons with less than 5 TER cases per year and those with more than 10 cases per year (Table 4).

Table 2.

Early complication rates

| No. of early complications (% of total at risk) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Complication | 90 days (n = 1,142) |

1 year (n = 1,078) |

| General | ||

| DVT/PE | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) |

| Death | 4 (0.4) | 13 (1.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (0.3) | 9 (0.8) |

| Implant-specific | ||

| Infection | 22 (1.9) | |

| Dislocation | 8 (0.7) | |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 35 (3.1) | |

DVT/PE: Deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism

Table 3.

Cumulative complication rate by annual surgeon volume

| 10-year complication rate (Kaplan-Meier) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average no. of procedures per surgeon per year |

n | Infection (n = 86) |

Dislocation (n = 9) |

Periprosthetic fracture (n = 45) |

| ≤ 4 | 394 | 8.3% | 0.9% | 0.3% |

| 5–9 | 339 | 8.7% | 0.3% | 1.4% |

| ≥ 10 | 413 | 7.6% | 1.6% | 2.1% |

| Total | 1,146 | 8.2% | 0.9% | 1.3% |

| p-value (log-rank) | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.9 | |

Table 4.

Primary diagnosis by annual surgeon volume

| Average no. of procedures per surgeon per year |

Primary diagnosis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory (n = 828) |

Osteoarthrosis (n = 93) |

Trauma (n = 65) |

Total (n = 986) |

|

| ≤ 4 | 217 (81%) | 27 (10%) | 23 (9%) | 267 |

| 5–9 | 272 (81%) | 41 (12%) | 25 (7%) | 338 |

| ≥ 10 | 339 (89%) | 25 (7%) | 17 (4%) | 381 |

| Total | 828 | 93 | 65 | 986 |

p = 0.01

Discussion

The main strength of this study was the national coverage derived from a central audit database. The use of record linkage allowed the detection of implant failure, even if this occurred at a different institution to the primary procedure. The data allowed the identification of trends in incidence over time among inflammatory arthropathies and trauma, and in the influence of etiology and surgeon experience on outcome. The main limitation was the lack of data related to implant type.

Over the 18-year period of this population-based study, the annual incidence of TER decreased due to a reduction in the number of TERs for rheumatoid arthritis, as a result of improved medical management. There was an increase in TERs for osteoarthritis and trauma, but the overall numbers were low. These results are similar to recently published data from a North American area with a similar size of population (Gay et al. 2012). The Norwegian registry reported on 562 TER procedures over a 13-year period (Fevang et al. 2009). Rheumatoid arthritis was the most common diagnosis, and the data showed a similar reduction in rate over time. The authors reported 10-year failure rates of 15%, which are similar our results. The worst outcomes were found in patients undergoing TER for fracture sequelae, where there was a relative risk of revision of 6 compared to inflammatory arthropathy.

Revision elbow replacement is a technically challenging procedure with issues of bone stock, soft tissue cover, and stability. Our study has shown that the revision rate following TER was high—15% at 18 years. The revision rate was higher with those surgeons who performed less than 5 procedures per year than with those who performed more than 10 per year. Our numbers were small, but this finding is in keeping with the results of similar studies on lower limb arthroplasty (Katz et al. 2004, Meek et al. 2006).

The complication rates that we found are in line with those in the literature. A recent systematic review reported that TER for posttraumatic complications had the highest complication rate of 38%, compared to 24% for inflammatory arthritis (Voloshin et al. 2011). This is in keeping with other case series (Fevang et al. 2009, Morrey and Schneeberger 2009). The rates of other complications such as thromboembolism and death within 90 days (Table 2) also agree with those in with previous reports (Duncan et al. 2007, Sanchez-Sotelo et al. 2007). The number of patients who sustained a type C distal humerus fracture was low, and even in the context of an aging population, may not generate a substantial widespread rise in the demand for TER (Robinson et al. 2003). There were more periprosthetic fractures at 10 years with those surgeons who had a higher annual volume (2.1% vs. 0.3%) (Table 3). This may reflect a variation in the underlying etiology. Surgeons who performed more TERs per year tended to operate on more patients with inflammatory arthropathy (Table 4). This group may have a greater risk of periprosthetic fracture due to reduced bone density.

The literature has consistently demonstrated that the best results of TER are in rheumatoid arthritis, and that the outcomes in high-demand groups (i.e. OA and acute fracture) are poorer (Skytta et al. 2009). That particular study also showed that there was an inverse relationship between the revision rate and the experience of the surgeon. The literature shows no clear benefit of one particular prosthesis over any other (Little et al. 2005). In the present study we were unable to identify the types of prostheses used.

A decreasing rate of TER raises serious questions regarding clinical governance and the maintainance of adequate levels of expertise. Experience based on 1–2 TERs per year can never give meaningful outcome data for an individual surgeon and unit, and is at risk of giving poorer outcomes (Shervin et al. 2007, Bozic et al. 2010). Whereas orthopedic surgeons at the end of their training are competent at hip and knee arthroplasty, few have had a comprehensive training in TER. The creation of a managed clinical referral network for elbow arthroplasty would ensure that procedures are performed by individuals with adequate experience, who are then able to teach, train, and audit in an appropriate environment.

Acknowledgments

PJ, AW, AD authored the manuscript. TN performed the data analysis. LR and JMcE set the research question, data analysis protocol and co-authored the manuscript.

The authors acknowledge the support and assistance provided by ISD Scotland. They also acknowledge the surgeons who have undertaken the procedures analysed in this study.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Bozic KJ, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Vail TP, Auerbach AD. The influence of procedure volumes and standardization of care on quality and efficiency in total joint replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010;92(16):2643–52. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SF, Sperling JW, Morrey BF. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism after total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(7):1452–3. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich GE. Incidence of elbow involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(7):1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Results after 562 total elbow replacements: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(3):449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay DM, Lyman S, Do H, Hotchkiss RN, Marx RG, Daluiski A. Indications and reoperation rates for total elbow arthroplasty: an analysis of trends in New York State. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94(2):110–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Registrar Office for Scotland http://www.gro-scotland.gov.uk/statistics/theme/population/estimates/mid-year/index.html Mid Year Population Estimates [online] [cited; 2011 (Jan 6). Available from: URL:

- Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004;86(9):1909–16. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little CP, Graham AJ, Karatzas G, Woods DA, Carr AJ. Outcomes of total elbow arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis: comparative study of three implants. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87(11):2439–48. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek RM, Allan DB, McPhillips G, Kerr L, Howie CR. Epidemiology of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2006;(447):9–18. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000218754.12311.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrey BF, Schneeberger AG. Total elbow arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthrosis. Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS National Services Scotland http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/servlet/FileBuffer?namedFile=SMR01%20Scotland%20Report%202007.pdf&pContentDispositionType=attachment NHS Hospital Data Quality: Towards Better Data from Scottish Hospitals [online] 2007 [cited; (26 April 2011). Available from: URL.

- Robinson CM, Hill RM, Jacobs N, Dall G, Court-Brown CM. Adult distal humeral metaphyseal fractures: epidemiology and results of treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17(1):38–47. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW, Morrey BF. Ninety-day mortality after total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(7):1449–51. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shervin N, Rubash HE, Katz JN. Orthopaedic procedure volume and patient outcomes: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop. 2007;(457):35–41. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180375514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shourt CA, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Orthopedic Surgery Among Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis 1980-2007: A Population-based Study Focused on Surgery Rates, Sex, and Mortality. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(3):481–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skytta ET, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Ikavalko M, Remes V. Total elbow arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(4):472–7. doi: 10.3109/17453670903110642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voloshin I, Schippert DW, Kakar S, Kaye EK, Morrey BF. Complications of total elbow replacement: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):158–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]