Abstract

Background and purpose

There is no substantial clinical evidence for the superiority of alternative bearings in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We compared the short-term revision risk in alternative surface bearing knees (oxidized zirconium (OZ) femoral implants or highly crosslinked polyethylene (HXLPE) inserts) with that for traditional bearings (cobalt-chromium (CoCR) on conventional polyethelene (CPE)). The risk of revision with commercially available HXLPE inserts was also evaluated.

Methods

All 62,177 primary TKA cases registered in a Total Joint Replacement Registry between April 2001 and December 2010 were retrospectively analyzed. The endpoints for the analysis were all-cause revisions, septic revisions, or aseptic revisions. Bearing surfaces were categorized as OZ-CPE, CoCr-HXLPE, or CoCr-CPE. HXLPE inserts were stratified according to brand name. Confounding was addressed using propensity score weights. Marginal Cox-regression models adjusting for surgeon clustering were used.

Results

The proportion of females was 62%. Average age was 68 (SD 9.3) years, and median follow-up time was 2.8 (IQR 1.2–4.9) years. After adjustments, the risks of all-cause, aseptic, and septic revision with CoCr-HXLPE and OZ-CPE bearings were not statistically significantly higher than with traditional CoCr-CPE bearings. No specific brand of HXLPE insert was associated with a higher risk of all-cause, aseptic, or septic revision compared to CoCr-CPE.

Interpretation

At least in the short term, none of the alternative knee bearings evaluated (CoCr-HXLPE or OZ-CPE) had a greater risk of all-cause, aseptic, and septic revision than traditional CoCr-CPE bearings.

First-generation highly crosslinked polyethylene (HXLPE) tibial inserts became commercially available for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in 2001 (Kurtz 2009). Since polyethylene wear is the major reason for osteolysis and related complications, it was assumed that HXLPE inserts would reduce wear, as has been observed in total hip arthroplasty (THA) patients (Kurtz et al. 2011). The success of HXLPE inserts in THA surgery was shown relatively soon after their introduction to the market in the late 1990s. Several clinical studies of THA inserts showed the benefit of this HXLPE, namely the reduced incidence of osteolysis and reduced wear compared to the conventional polyethylene (CPE) (Kurtz et al. 2011).

The degradation of the material properties of polyethylene after crosslinking is a concern. The locking mechanisms holding an insert to the tibial tray often require the creation of grooves, or cutouts, in the polyethylene. These areas of reduced material—in a material that may be more prone to fatigue failure—could lead to implant breakage, resulting in dislocation of the liner from the tray (Kurtz 2009).

As with tibial insert materials, femoral component material has been explored as another way of reducing tibial insert wear in TKA. Femoral components are usually made of cobalt-chromium alloy (CoCr), but ceramic biomaterials—known for their hardness, potential for reduced wear, and biocompatibility—have been explored. Alumina ceramic femoral components have shown lower wear rates than CoCr components in some laboratory studies (Oonishi et al. 2009), and clinical studies in Japan have explored the use of zirconia ceramic. Oxidized zirconium (OZ) is produced in a proprietary process (Oxinium; Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN) from zirconium alloy. When oxidized, the zirconium metal surface transforms into a layer of zirconia ceramic, and has shown promise of having reduced wear in laboratory studies (Ezzet et al. 2004, 2012, Tsukamoto et al. 2006) and early follow-up clinical studies (Bal et al. 2006, Innocenti et al. 2010).

To our knowledge, no population-based studies evaluating the benefit of introduction of these alternative bearings to TKA have been conducted, and evaluations of the survival and early in vivo assessment of these bearings are lacking from the literature. In this study, we used a large Total Joint Replacement Registry (TJRR) to assess the short-term outcomes of the newly introduced knee bearing surfaces and HXLPE formulations. Specifically, we (1) compared the risks of all-cause, aseptic, and septic revision in the OZ-CPE and CoCr-HXLPE bearing surfaces with those for CoCr-CPE bearings, and (2) evaluated the risks of all-cause, aseptic, and septic revision for each of the HXLPE types and compared them with those for CPE.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data was conducted using a large TJRR as the data source for cohort and outcome identification. Data collection procedures, participation, and coverage of this TJRR have already been published (Paxton et al. 2008, 2010a, b, 2012). Briefly, the TJRR covers 9 million members of an integrated healthcare system, in 8 geographical regions of the USA and enrolls over 20,000 joint arthroplasties a year. Participation in the registry is voluntary and participation rates are high (Paxton et al. 2012). The study sample involved patients from 48 medical centers and 393 surgeons. All elective primary TKAs for any diagnosis registered between April 1, 2001 and December 31, 2010 were included in the sample. Patients having TKA revisions, unicompartmental knee arthroplasties, conversions to a primary TKA from a previous knee operation—or those with implants classified as constrained by their polyethylene insert, femoral component, or tibial tray—were not included in the study sample.

Outcome of interest

Revision procedure was the outcome of interest. All-cause revision included procedures for any reason where removal and re-implantation of a TKA component occured after the original index procedure had occurred. Aseptic revision was defined as a revision for non-infectious reasons after the original index procedure had occurred. Septic revision was defined as revision for infection after the original procedure. Only the first revisions were included in this study. This information is collected by the TJRR prospectively for all cases through a process of active surveillance (using the electronic health records of the integrated healthcare system to monitor the patient’s activity), passive surveillance (surgeon reporting to the TJRR data repository center), and adjudication of identified cases to assure that all fit the pre-specified definition of the event.

Main exposures

Information regarding tibial insert material and femoral component material used to identify the knee bearing surface was obtained from the TJRR. The registry uses implant label descriptions and experienced surgeons to classify implant attributes such as size, material, side, and other special features of the implant. Of primary interest was the comparison of the main bearing surfaces: CoCr-CPE, OZ-CPE, and CoCr-HXLPE. In secondary analyses, we subclassified CoCr-HXLPE based on brand. The following HXLPE inserts were included: Durasul (Zimmer Inc., Warsaw, IN), Prolong (Zimmer), and Sigma XLK (Depuy Inc., Warsaw, IN). Due to the small numbers (n = 448) of the other 3 HXLPE types identified—Triathlon X3 (Stryker Orthopaedics, Mahwah, NJ), Vanguard E Poly (Biomet Orthopedics, Warsaw, IN), and Legion HXLPE (Smith and Nephew Inc., Memphis, TN)—they were not included in the analysis.

Confounding/covariate influences

Variables, identified from the literature or by our clinical experts, and internal analysis as possible confounders were adjusted for in our models using propensity score weights. The following variables were included in the model as continuous covariates: age (Santaguida et al. 2008), operative time (Pulido et al. 2008), body mass index (BMI) (Namba et al. 2005, Jamsen et al. 2009, Jones et al. 2012), surgeon yearly average volume, hospital yearly average volume, and number of procedures performed by the surgeon with specific bearing design (Manley et al. 2009, Bozic et al. 2010). Surgeon and hospital yearly average volume were based on both the primary and the revision procedures performed by the surgeon or institution. The model was also adjusted for the following categorical covariates: sex (Santaguida et al. 2008), ASA score (2 categories) (Paxton et al. 2010a), diabetes diagnosis (Paxton et al. 2010a), race (5 categories) (Ong et al. 2010), implant fixation (3 categories) (Berger et al. 2001, Robertsson et al. 2001), bilateral procedure (Memtsoudis et al. 2011), and surgeon total joint arthroplasty fellowship training status.

Statistics

Frequencies, proportions, means (SD), and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are used to describe the overall sample included in this study and the cases in each of the main bearing surfaces groups. Student t-test and chi-square tests were used to compare the implant groups under the null hypothesis of no difference. Revision rate per 100 years of observation (revision density and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)), and reasons for revision were also studied for the overall sample, for the main bearing surface categories, and for each HXLPE brand name. Revision rate per 100 years of observation was compared using Poisson regression. Given the non-randomized nature of the bearing surface group assignment, counfounding was addressed using a weighted propensity score approach (Hong 2010, 2012). Missing data were handled using multiple imputation. The variables with missing data that required imputation included bearing surface, ASA score, BMI, race, implant fixation, sex, age, fellowship training, mobility/stability categorization, and operative time. 20 imputed data sets were created and Rubin’s rules for aggregating parameter estimates and variances were used (Rubin 1987). Marginal Cox-regression models for multivariate survival data that adjusted for surgeon clustering (due to the potential lack of independence amongst the observations (Lin and Wei 1989) were fit with propensity score weights for each imputed data set and the results were subsequently aggregated across data sets.

All analyses used CoCr-CPE as the reference group. Hazard ratios (HRs) are the estimated revision risks reported. HR, 95% CIs and Wald p-values are provided. For the primary analysis models, individuals not experiencing a revision, terminating membership or dying prior to experiencing a revision were treated as censored cases, with survival calculated as time from surgery to each of these alternative events. Sensitivity analyses were performed using best and worst case scenarios to address loss to follow-up (Allison 1995). In best case scenario, lost to follow-up cases had censored survival times calculated based on the end of the study period date, not their membership termination/death date. In the worst case scenario, a random sample of 10% of the lost to follow-up cases were assumed to experience the event one day after their membership termination/death date. Data were analyzed using SAS (Version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and p < 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

Ethics

The Kaiser Permanente Internal Review Board approved the study in August 2009 (number 5488, with recent renewal June 2012).

Results

Cohort characteristics

During the study period, 62,177 primary TKAs that fit our study criteria were registered in the TJRR. The mean age of this cohort was 68 (SD 9.3) years and 62% of them were females. The cohort was followed for a median time of 2.8 (IQR: 1.2–4.9) years; 4.8% (n = 2,960) of the cases died and 9.0% (n = 5,609) were lost to follow-up. There were 1,362 revisions (2.2%), 789 aseptic revisions (1.3%) and 573 septic revisions (0.9%). The all-cause revision rate per 100 years of observation for the entire cohort was 0.68% (CI: 0.64-0.71). The aseptic and septic revision rates per 100 years of observation were 0.39% (CI: 0.37–0.42) and 0.29% (CI: 0.26–0.31), respectively.

Altogether, 78.9% of the cohort (n = 49,055) had traditional bearings. 12.3% (n = 7,618) had CoCr-HXLPE bearings and 1.7% (n = 1, 066) had OZ-CPE bearings (Table 1). Median follow-up time was 3.0 (IQR: 1.3–5.2) years for the CoCr-CPE bearing group, 2.9 (IQR: 1.5–4.4) years for the OZ-CPE bearing group, and 1.8 (IQR: 0.7–3.3) years for the CoCr-HXLPE bearing group. There were 4,438 cases (7.1%), with a median follow-up of 3.2 (IQR: 1.5–4.9) years, where the bearing surface could not be determined. Different distributions of patient characteristics were observed for age, sex, race, ASA score, and BMI categories by bearing surface type. There were also different distributions in all the procedure/implant and surgeon/hospital variables by bearing surface type.

Table 1.

Patients, procedures, implants, and surgeon and hospital characteristics, listed according to bearing surface

| Total cohort | CoCr-HXLPE | CoCr-CPE | OZ-CPE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 62,177) | (n = 7,618) | (n = 49,055) | (n = 1,066) | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Female a | 38,828 (62.4) | 4,692 (61.6) | 30,864 (62.9) | 608 (57.0) | < 0.001 |

| Mean age (SD), years a | 67.5 (9.3) | 65.7 (9.4) | 67.8 (9.2) | 59.7 (8.4) | < 0.001 |

| ASA score | |||||

| 1 or 2 | 37,090 (59.7) | 4,536 (59.5) | 29,196 (59.5) | 656 (61.5) | 0.002 |

| > 3 | 23,593 (37.9) | 2,719 (35.7) | 18,910 (38.5) | 373 (35) | |

| Unknown | 1494 (2.4) | 363 (4.8) | 949 (1.9) | 37 (3.5) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| < 30 | 2,6314 (42.3) | 2,882 (37.8) | 21,028 (42.9) | 339 (31.8) | < 0.001 |

| 30–35 | 18,066 (29.1) | 2,251 (29.5) | 14,191 (28.9) | 323 (30.3) | |

| ≥ 35 | 16,597 (26.7) | 2,396 (31.5) | 12,840 (26.2) | 385 (36.1) | |

| Unknown | 1,200 (1.9) | 89 (1.2) | 996 (2.0) | 19 (1.8) | |

| Race | |||||

| Asian | 3,034 (4.9) | 274 (3.6) | 2,563 (5.2) | 28 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Black | 4,868 (7.8) | 783 (10.3) | 3,718 (7.6) | 153 (14.4) | |

| White | 41,640 (67) | 5,217 (68.5) | 32,483 (66.2) | 646 (60.6) | |

| Hispanic | 7,633 (12.3) | 843 (11.1) | 6,187 (12.6) | 134 (12.6) | |

| Other b | 1,282 (2.1) | 148 (1.9) | 1,057 (2.2) | 12 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 3,720 (6.0) | 353 (4.6) | 3,047 (6.2) | 93 (8.7) | |

| Diabetes | 16,465 (26.5) | 2,036 (26.7) | 13,012 (26.5) | 275 (25.8) | 0.8 |

| Procedure/implant characteristics | |||||

| Bilateral | 5,311 (8.5) | 510 (6.7) | 42,74 (8.7) | 113 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

| Mean operative time (SD), min a | 95.1 (32.5) | 96.8 (31.7) | 95 (32.6) | 105 (36.8) | < 0.001 |

| Implant fixation | |||||

| Uncemented | 1,874 (3.0) | 207 (2.7) | 969 (2.0) | 3 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hybrid | 3,137 (5.0) | 570 (7.5) | 2,447 (5.0) | 8 (0.8) | |

| Cemented | 53,379 (85.9) | 6,263 (82.2) | 42,785 (87.2) | 989 (92.8) | |

| Unknown | 3787 (6.1) | 578 (7.6) | 2854 (5.8) | 66 (6.2) | |

| Mobility and stability | |||||

| Fixed: Cruciate retaining | 15,811 (25.4) | 3,922 (51.5) | 10,736 (21.9) | 404 (37.9) | < 0.001 |

| Fixed: Posterior stabilized | 38,516 (61.9) | 3,695 (48.5) | 31,377 (64.0) | 662 (62.1) | |

| Rotate: Cruciate retaining | 858 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 856 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Rotate: Low contact stress | 1,040 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1,020 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Rotate: Posterior stabilized | 5,096 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5,063 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 856 (1.4) | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| High flexion | 7,583 (12.2) | 3,363 (44.1) | 3,659 (7.5) | 443 (41.6) | < 0.001 |

| Surgeon/hospital characteristics | |||||

| Joint arthroplasty fellowship training a | 21,551 (34.7) | 2,404 (31.6) | 17,254 (35.2) | 430 (40.3) | < 0.001 |

| Surgeon volume, cases/year a | |||||

| < 10 | 1,092 (1.8) | 184 (2.4) | 791 (1.6) | 35 (3.3) | < 0.001 |

| 10–49 | 26,447 (42.5) | 3,231 (42.4) | 21,040 (42.9) | 516 (48.4) | |

| ≥ 50 | 34,638 (55.7) | 4,203 (55.2) | 27,224 (55.5) | 515 (48.3) | |

| No. of cases performed by surgeon, median (IQR) | 95 (33–205) | 39 (13–98) | 117 (48–235) | 14 (5–40) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital volume, cases/year a | |||||

| < 99 | 2,022 (3.3) | 438 (5.7) | 1442 (2.9) | 63 (5.9) | < 0.001 |

| 100–199 | 11,443 (18.4) | 1,082 (14.2) | 9,604 (19.6) | 264 (24.8) | |

| ≥ 200 | 48,712 (78.3) | 6,098 (80) | 38,009 (77.5) | 739 (69.3) |

a Missing data: sex < 0.1%, age < 0.1%, operative time 17.7%, fellowship training 0.1%.

b Includes native American, multi-race, and other.

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists score; BMI: body mass index; HXLPE: highly crosslinked polyethylene;

CoCr: cobalt-chromium; CPE: conventional polyethylene; OZ: oxidized zirconium.

Revision rates (Figures 1 and 2))

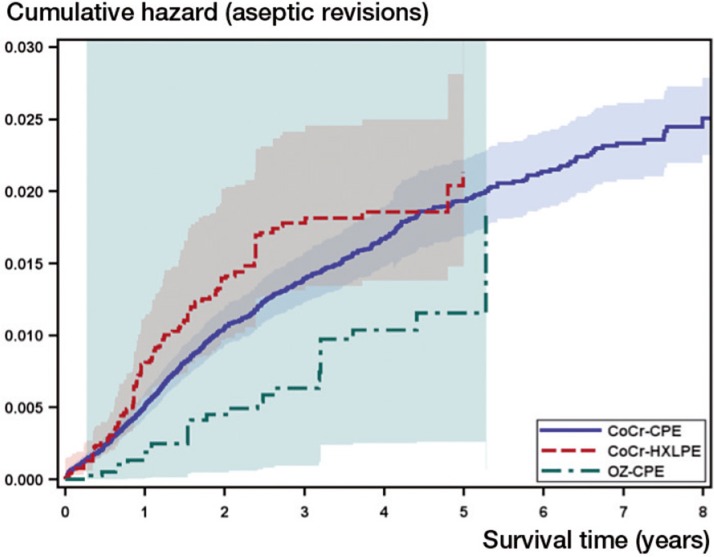

Figure 1.

Adjusted cumulative hazard function estimate by knee bearing surface; aseptic revisions only. Adjustment based on the propensity score weights with stratification on the bearing surface groups using data from one of the 20 imputed data sets. HXLPE: highly crosslinked polyethylene; CoCr: cobalt-chromium; CPE: conventional polyethylene; OZ: oxidized zirconium.

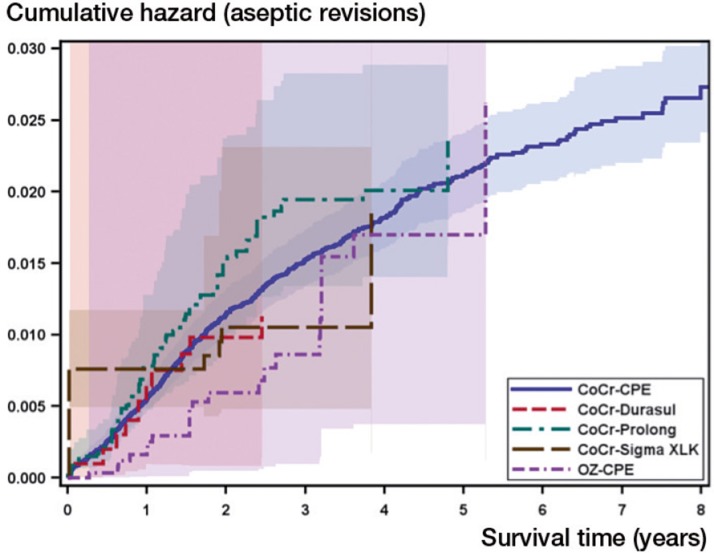

Figure 2.

Adjusted cumulative hazard function estimate by knee bearing surface with stratification by highly crosslinked materials; aseptic revisions only. Adjustment based on the propensity score weights with stratification on the bearing surface groups using data from one of the 20 imputed data sets. For abbreviations, see Figure 1.

The all-cause, aseptic, and septic revision rates per 100 years of observation were statistically significantly different for the main bearing surfaces (Table 2). OZ-CPE bearings had the highest all-cause and aseptic revision rates per 100 years of observation (1.01% and 0.67%, respectively; p < 0.05). CoCr-HXLPE had the highest septic revision rate per 100 years of observation (0.43%). The main reasons for revision were similar between groups, with infection, instability, pain, arthrofibrosis, and aseptic loosening being the most common diagnoses. Tibial insert polyethylene wear was the reason for revision in 1.1% of the whole cohort, and ranged from highest in the OZ-CPE group (3%) to lowest in the CoCr-HXLPE (0%) group. No failures due to tibial liner displacement, fracture, fatigue failure, or dislocation were observed during the study period.

Table 2.

All-cause, aseptic, and septic revision rates per 100 observation years, and reasons for revision for the overall cohort, listed according to bearing surface a

| Total cohort b | CoCr-HXLPE | CoCr-CPE | OZ-CPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 62,177) | (n = 7,618) | (n = 49,055) | (n = 1,066) | |

| All-cause revisions, n c | 1,362 | 157 | 1,095 | 33 |

| Total observation years | 201,014 | 16,478 | 166,224 | 3,276 |

| Revisions per 100 obs. years, % (95% CI) | 0.68 (0.64–0.71) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 0.66 (0.62–0.7) | 1.01 (0.72–1.42) |

| Aseptic revisions, n d | 789 | 86 | 626 | 22 |

| Total observation years | 201,014 | 16,478 | 166,224 | 3,276 |

| Revisions per 100 obs. years, % (95% CI) | 0.39 (0.37–0.42) | 0.52 (0.4 –0.64) | 0.38 (0.35–0.41) | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) |

| Septic revisions, n e | 573 | 71 | 469 | 11 |

| Total observation years | 201,014 | 16,478 | 166,224 | 3,276 |

| Revisions per 100 obs. years, % (95% CI) | 0.29 (0.26–0.31) | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | 0.28 (0.26–0.31) | 0.34 (0.19–0.61) |

| Reasons for revision f | ||||

| Infection | 573 (42.1) | 71 (45.2) | 469 (42.8) | 11 (33.3) |

| Instability | 258 (18.9) | 43 (27.4) | 196 (17.9) | 9 (27.3) |

| Pain | 238 (17.5) | 25 (15.9) | 187 (17.1) | 7 (21.2) |

| Aseptic loosening | 178 (13.1) | 11 (7.0) | 152 (13.9) | 2 (6.1) |

| Arthrofibrosis | 136 (10.0) | 15 (9.6) | 108 (9.9) | 7 (21.2) |

| Femoral fracture | 27 (2.0) | 2 (1.3) | 21 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Polyethylene liner wear | 16 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.3) | 1 (3.0) |

| Hematoma | 15 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 14 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Patello-femoral joint malfunction | 15 (1.1) | 2 (1.3) | 12 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Wound dehiscence | 11 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Wound drainage | 12 (0.9) | 3 (1.9) | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Failed extensor mechanism | 9 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Synovial impingement | 9 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ingrowth failure | 10 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Seroma | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Tibial fracture | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 70 (5.1) | 9 (5.7) | 54 (4.9) | 2 (6.1) |

a Comparison of revision rate per 100 observation years was analyzed using Poisson regression with exact tests. No adjustments were made for confounders.

b Inclusive of cases with missing bearing surface.

c Overall comparison of all-cause revision per 100 observation years across groups, p < 0.001. Contrasts: CoCr-HXLPE vs. CoCr-CPE, p < 0.001; OZ-CPE vs. CoCr-CPE, p = 0.03.

d Overall comparison of aseptic revision per 100 observation years across groups, p = 0.001. Contrasts: CoCr-HXLPE vs. CoCr-CPE, p = 0.007; OZ-CPE vs. CoCr-CPE p=0.02.

e Overall comparison of septic revision per 100 observation years across groups, p=0.005. Contrasts: CoCr-HXLPE vs. CoCr-CPE p=0.002. OZ-CPE vs. CoCr-CPE p=0.7.

f Number (%), reasons for revision (except for infection) are not mutually exclusive.

For other abbreviations, see Table 1.

Table 3.

All-cause, aseptic, and septic revision rates per 100 observation years, and reasons for revision, listed according to type of highly crosslinked polyethylene (all on cobalt-chromium alloy) a

| Total CoCr-HXLPE | CoCr-Durasul | CoCr-Prolong | CoCr-Sigma XLK | CoCr-Other HXLPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7,618) | (n = 557) | (n = 5,132) | (n = 1,481) | (n = 448) | |

| All-cause revisions, n b | 157 | 20 | 115 | 18 | 4 |

| Total observation years | 16,478 | 1,908 | 11,713 | 2,431 | 427 |

| Revisions per 100 obs. years, % (95% CI) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 1.05 (0.68–1.62) | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | 0.74 (0.47–1.18) | 0.94 (0.35–2.50) |

| Aseptic revision, n c | 86 | 13 | 66 | 4 | 3 |

| Total observation years | 16,478 | 1,908 | 11,713 | 2,431 | 427 |

| Revisions per 100 obs. years, % (95% CI) | 0.52 (0.42–0.64) | 0.68 (0.40–1.17) | 0.56 (0.44–0.72) | 0.16 (0.06–0.44) | 0.70 (0.23–2.18) |

| Septic revision, n d | 71 | 7 | 49 | 14 | 1 |

| Total observation years | 16,478 | 1,908 | 11,713 | 2,431 | 257 |

| Revisions per 100 obs. years, % (95% CI) | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | 0.37 (0.17–0.77) | 0.42 (0.32–0.55) | 0.58 (0.34–0.97) | 0.39 (0.05–2.76) |

| Reasons for revision e | |||||

| Infection | 71 (45.2) | 7 (35.0) | 36 (39.6) | 14 (77.8) | 1 (25.0) |

| Instability | 43 (27.4) | 3 (15.0) | 39 (33.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| Pain | 25 (15.9) | 3 (15.0) | 19 (16.5) | 3 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Arthrofibrosis | 15 (9.6) | 4 (20.0) | 9 (7.8) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (25.0) |

| Aseptic loosening | 11 (7.0) | 2 (10.0) | 6 (5.2) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (25.0) |

| Wound drainage | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Femoral fracture | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ingrowth failure | 2 (1.3) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Patello-femoral joint malfunction | 2 (1.3) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Synovial impingement | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hematoma | 1 (0.6) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Failed extensor mechanism | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Polyethylene liner wear | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 9 (5.7) | 1 (5.0) | 7 (6.1) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

a Comparison of revision rate per 100 observation years was analyzed using Poisson regression with exact tests. No adjustments were made for confounders.

b Overall comparison of all-cause revision per 100 observation years across groups, p = 0.7. No contrasts were performed because the overall test was not significant.

c Overall comparison of aseptic revision per 100 observation years across groups, p = 0.02. Contrasts: CoCr-Durasul vs. CoCr-Prolong, p = 0.6; CoCr-Other HXLPE vs. CoCr-Prolong, p = 0.9; CoCr-Sigma XLK vs. CoCr-Prolong, p = 0.009.

d Overall comparison of septic revision per 100 observation years across groups, p = 0.7. No contrasts were performed because the overall test was not significant.

e Number (%), reasons for revision (except for infection) are not mutually exclusive.

For other abbreviations, see Table 1.

In the HXLPE subgroup analysis, CoCr-Other HXLPE group had the highest aseptic revision rate per 100 years of follow-up (0.70%) and the CoCr-Sigma XLK group had the lowest (0.16%) (p = 0.02). The reasons for revision in the groups were different. In the CoCr-Durasul group and the CoCr-Prolong group, the top 4 reasons were infection, instability, pain, and arthrofibrosis. In the CoCr-Sigma XLK group, the main reasons for failure were infection, pain, and aseptic loosening. Finally, in the CoCr-Other HXLPE group, the reasons for the 4 revised cases were infection, arthrofibrosis, and aseptic loosening. No failures due to tibial insert displacement, fracture, fatigue failure, or dislocation were found.

Risk of revision

After adjusting for patient factors (age, sex, ASA, diabetes, race, BMI) and procedural factors (bilateral, operative time, surgeon and hospital yearly average volume, number of procedures performed by a surgeon using a specific implant design, surgeon arthroplasty fellowship training status, and fixation) there was no statistically significant difference in risk of all-cause, aseptic, and septic revision between the knee bearing types evaluated (in model 1 (the main bearing model) or 2 (the stratified HXLPE model)). For all-cause revision, an HR of 1.2 (CI: 0.9–1.5) was observed for CoCr-HXLPE and an HR of 1.4 (CI: 0.3–5.9) was observed for OZ-CPE compared to CoCr-CPE bearings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Propensity score weighted regression results for risks from all causes, and of aseptic and septic revision, according to type of knee bearing. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence Intervals

| All-cause |

Aseptic |

Septic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| CoCr-HXLPE vs. CoCr-CPE | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.2 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.2 | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.6 |

| OZ-CPE vs. CoCr-CPE | 1.4 (0.3–5.9) | 0.7 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.3 | 2.2 (0.3–16.3) | 0.4 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| CoCr-Durasul vs. CoCr-CPE | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.6 | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) | 0.5 | 1.2 (0.6–2.2) | 0.6 |

| CoCr-Prolong vs. CoCr-CPE | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.4 | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 0.5 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.7 |

| CoCr-Sigma XLK vs. CoCr-CPE | 1.1 (0.4–3.1) | 0.9 | 1.2 (0.2–6.8) | 0.8 | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) | 0.9 |

| OZ-CPE vs. CoCr-CPE | 1.5 (0.4–5.1) | 0.6 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.4 | 2.4 (0.4–14.4) | 0.3 |

Risk-of-revision estimates were consistent in our sensitivity analysis, including the worst case scenario where 10% of the cases lost to follow-up were considered to be revised.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report on a large cohort of alternative-bearing knees with a comparison of all-cause, aseptic, and septic risk of failure. 2 case series (Laskin 2003, Innocenti et al. 2010) and 1 randomized control trial (Hui et al. 2011) have been published evaluating the short- to medium-term survival of OZ femoral components. In the study by Innocenti et al. (2010), younger, healthier, more active patients were selected to receive the OZ implants. This type of patient selection, as the authors themselves suggested, could have biased their findings. In the 2.5 years of mean follow-up in that study, no knees were revised and only 1 knee had radiographic evidence of aseptic loosening. The series of patients reported by Laskin (2003), which have now featured in more than one study, had no revisions or aseptic loosening at 5 years follow-up. Both Innocenti et al. and Laskin et al. had limited capacity for multivariable adjustments due to small numbers of events. Because of their lack of a comparable sample with a different bearing type, no estimation of risk could be made. In the randomized controlled trial published by Hui et al. (2011), which involved 40 patients and 80 knees (1 with CoCr and 1 with OZ femoral components), no differences in clinical, subjective, or radiographic outcomes were found 1, 2, and 5 years postoperatively. 2 patients (4 knees) were revised in this study during the follow-up (corresponding to a revision rate of 3% for each femoral component type) and no differences in wear pattern were reported in the retrieved components. The small sample size in this study did not permit estimation of revision risk, and the statistical analysis ignored the dependence of the observations included, which raises questions about the authors’ interpretations.

Only 2 clinical studies evaluating the survival of HLXPE in knees have been published. Hodrick et al. (2008) and Minoda et al. (2009) conducted comparative studies of HLXPE and CPE bearings. Minoda et al. compared 89 knees with Prolong HLXPE to 113 knees with CPE 2 years after surgery (Minoda et al. 2009). The authors reported no revisions, osteolysis, or loosening, and there was a non-statistically significant difference in tibial and femoral component radiolucency. In the study by Hodrick et al., a group of 100 subjects who received Durasul HXLPE were compared to 100 subjects who received CPE and the two groups were not found to have significantly different revision rates. The Durasul group had 2 tibial radiolucencies and no sign of loosening or polyethylene wear at an average of 6 years postoperatively. The CPE group, at an average follow-up of 7 years, had 20 patients with radiolucencies and 4 patients with tibial loosening (Hodrick et al. 2008). While these 2 studies had comparative groups, no stratifications or adjustments could be carried out due to the small sample sizes.

Since the present study was observational and the presence of confounding could bias the estimates presented, we used propensity scores to adjust for measured confounders. Confounding is an important issue that arises in non-experimental studies such as ours. Regression adjustment is the most traditional method of analytical confounding adjustment, but it only works well if certain restrictive distributional assumptions are made (Rubin 2001). Propensity-scores methods do not have such restrictions. The median follow-up time of the cohort in our study of 2.8 years was not long enough to detect some of the possible failures, namely osteolysis, or other longer-term polyethylene insert wear problems of the alternative bearings evaluated. Our findings are, however, short- to medium-term assessments of a large cohort and we hope to reassess the risk of revision in these patients when longer follow-up is available.

Using revision as the endpoint in the analysis was also another limitation of this study. The data obtained from this study were from a TJRR where certain detailed variables—such as radiographic evidence (or documentation of the radiolucency development or loosening)—are sacrificed for the sake of greater efficiency in registering and monitoring large cohorts of patients. The study was also limited by the number of events in each of the subgroups analyzed. Some of our estimations, specifically our septic risk estimations, had a lot of uncertainty (wide confidence intervals) and should be interpreted with care. Loss to follow-up was also a limitation, which was partially addressed by conducting sensitivity analyses that demonstrated no major differences in results under various assumed scenarios of what might have happened to patients had they not been lost to follow-up.

The large number of cases and events in our study, the methodology used, the ability to evaluate several brand names of HXLPE, and the large number of participating surgeons, patients, and hospitals in the sample, were some of the strengths of this study. Due to the large sample size, 3 brands of HXLPE were individually evaluated. Additionally, the diversity of the large number of participating sites (48) and surgeons (393) contributing data to the TJRR increased its representativeness of the orthopedic community, and therefore the generalizability of the results presented. Not only were high-volume surgical centers and highly trained surgeons contributing to the arthroplasty cases included in the analysis, but smaller centers and non-fellowship-trained surgeons were also included. The study also had high internal validity, as all the information was defined, assembled, and managed by one common data collection and repository center. Management of the information collected by the TJRR registry is performed using common/standard definitions, high-level data quality management techniques, and adjudication of all outcome information by trained research personnel. Internal validity was also high, as proper confounding adjustment techniques were used in the analysis of the data.

In conclusion, this study did not show any evidence of deleterious effects of the use of alternative bearings for TKA on short-term outcomes. Longer follow-up will be required to determine whether the potential benefits of wear reduction justify continued use of these bearings.

Acknowledgments

Study concept and design: MCSI, GC, EWP, SMK, and RSN. Extraction of data and preparation of raw data: MCSI and GC. Statistical analysis: GC. Interpretation of data: MCSI, GC, EWP, and RSN. Drafting of the manuscript (text): MCSI. Drafting of figures and tables: MCSI and GC. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CSI, GC, EWP, SMK, and RSN.

We thank all the Kaiser Permanente orthopedic surgeons who contribute to the Total Joint Replacement Registry, and the Surgical Outcomes and Analysis Department which coordinates registry operations. We also thank Chelsea E. Reyes for her support with the implant attributes classification, Cindy Y. Chen for her assistance with data management and preparation for the study, and Mary-Lou Kiley for her assistance with manuscript editing.

The institution of one of the authors (SMK) receives funding from Zimmer, DePuy, Stryker, and Biomet.

References

- Allison P. Cary, North Carolina: SAS Press; 1995. Survival analysis using SAS: A practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- Bal BS, Greenberg DD, Buhrmester L, Aleto TJ. Primary TKA with a zirconia ceramic femoral component. J Knee Surg. 2006;19(2):89–93. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RA, Lyon JH, Jacobs JJ, Barden RM, Berkson EM, Sheinkop MB, et al. Problems with cementless total knee arthroplasty at 11 years followup. Clin Orthop. 2001;(392):196–207. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic KJ, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Vail TP, Auerbach AD. The influence of procedure volumes and standardization of care on quality and efficiency in total joint replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010;92(16):2643–52. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzet KA, Hermida JC, Colwell CW, Jr., D’Lima DD. Oxidized zirconium femoral components reduce polyethylene wear in a knee wear simulator. Clin Orthop. 2004;(428):120–4. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000148576.70780.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzet KA, Hermida JC, Steklov N, D Lima DD. Wear of polyethylene against oxidized zirconium femoral components effect of aggressive kinematic conditions and malalignment in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(1):116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodrick JT, Severson EP, McAlister DS, Dahl B, Hofmann AA. Highly crosslinked polyethylene is safe for use in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(11):2806–12. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G. Marginal mean weighting through stratification: Adjustment for selection bias in multilevel data. J Education Behavior Statist. 2010;35:499–531. [Google Scholar]

- Hong G. Marginal mean weighting through stratification: a generalized method for evaluating multivalued and multiple treatments with nonexperimental data. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(1):44–60. doi: 10.1037/a0024918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C, Salmon L, Maeno S, Roe J, Walsh W, Pinczewski L. Five-year comparison of oxidized zirconium and cobalt-chromium femoral components in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93(7):624–30. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti M, Civinini R, Carulli C, Matassi F, Villano M. The 5-year results of an oxidized zirconium femoral component for TKA. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(5):1258–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamsen E, Huhtala H, Puolakka T, Moilanen T. Risk factors for infection after knee arthroplasty. A register-based analysis of 43,149 cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009;91(1):38–47. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CA, Cox V, Jhangri GS, Suarez-Almazor ME. Delineating the impact of obesity and its relationship on recovery after total joint arthroplasties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(6):511–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM. The UHMWPE biomaterials handbook: ultra high molecular weight polyethylene in total joint replacement and medical devices. In: Kurtz S M, editor. 2nd. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM, Gawel HA, Patel JD. History and systematic review of wear and osteolysis outcomes for first-generation highly crosslinked polyethylene. Clin Orthop. 2011;469(8):2262–77. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1872-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin RS. An oxidized Zr ceramic surfaced femoral component for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2003;(416):191–6. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093003.90435.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Statis Assoc. 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- Manley M, Ong K, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Total knee arthroplasty survivorship in the United States Medicare population: effect of hospital and surgeon procedure volume. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(7):1061–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memtsoudis SG, Ma Y, Chiu YL, Poultsides L, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Mazumdar M. Bilateral total knee arthroplasty: risk factors for major morbidity and mortality. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(4):784–90. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182282953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoda Y, Aihara M, Sakawa A, Fukuoka S, Hayakawa K, Tomita M, et al. Comparison between highly cross-linked and conventional polyethylene in total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2009;16(5):348–51. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba RS, Paxton L, Fithian DC, Stone ML. Obesity and perioperative morbidity in total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty (Suppl 3) 2005;20(7):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KL, Lau E, Suggs J, Kurtz SM, Manley MT. Risk of subsequent revision after primary and revision total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(11):3070–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oonishi H, Ueno M, Kim SC, Iwamoto M, Kyomoto M. Ceramic versus cobalt-chrome femoral components; wear of polyethylene insert in total knee prosthesis. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(3):374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E, Inacio M, Slipchenko T, Fithian D. The Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry. Perm J. 2008;12(3):12–6. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E, Namba R, Maletis G, Khatod M, Yue E, Davies M, et al. A prospective study of 80,000 total joint and 5,000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction procedures in a community-based registry in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2010a;92:117–32. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton EW, Inacio MC, Khatod M, Yue EJ, Namba RS. Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry: aligning operations with information technology. Clin Orthop. 2010b;468(10):2646–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1463-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton EW, Inacio M CS, Kiley ML. The Kaiser Permanente Implant Registries: Effect on patient safety, quality improvement, cost effectiveness, and research opportunities. Perm J. 2012;16(2):33–40. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(7):1710–5. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0209-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 1975-1997: an update with special emphasis on 41,223 knees operated on in 1988-1997. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):503–13. doi: 10.1080/000164701753532853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. New York: Wiley; 1987. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method. 2001;2:169–88. [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida PL, Hawker GA, Hudak PL, Glazier R, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, et al. Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Can J Surg. 2008;51(6):428–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto R, Chen S, Asano T, Ogino M, Shoji H, Nakamura T, et al. Improved wear performance with crosslinked UHMWPE and zirconia implants in knee simulation. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(3):505–11. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]