Abstract

Background and purpose

Unicompartmental to total knee arthroplasty revision surgery can be technically demanding. Joint line restoration, rotation, and augmentations can cause difficulties. We describe a new technique in which single-way fitting guides serve to position the knee system cutting blocks.

Method

Preoperatively, images of the distal femur and proximal tibia are taken using CT scanning. These images are used to create a patient-specific guide that fits in one single position on the contours of the bone and the prosthesis in situ. The guides are fixed with pins and then removed. The pins determine the position of the cutting blocks. 10 consecutive revisions were performed using this technique.

Results

All guides fitted well. 7 of 10 femoral prostheses were within the desired AP and sagittal angle ± 3°. However, 1 proximal tibia did not have enough bone stock on the medial plateau for adequate fixation of the guide, so conversion to intramedular referencing was performed. This was to be expected after the preoperative planning. All tibial components were within the desired AP angle ± 3° and 7 of 10 were within the desired sagittal angle. Hip-knee-ankle angle was within 0 ± 3° in 8 of 10 cases.

Interpretation

This new technique makes preoperative planning and execution of this plan during surgery less demanding. Problems such as the need for augmentations can be predicted at the preoperative planning. The instrumentation must be redesigned in order to make this technique work in cases where there is minimal bone stock present.

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is a widely used procedure for medial compartmental osteoarthritis of the knee. Revision rates of 6–13% have been reported (Vardi and Strover 2004, Oduwole et al. 2009). Oduwole et al. (2009) reported that due to possible bone loss, the potential need for augmentations, and use of long-stem prostheses, insertion of a new total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the proper position can be technically demanding. However, others have found it to be straightforward and less technically demanding than revision TKA (McAuley et al. 2001, Dudley et al. 2008, Oduwole et al. 2009). Both Dudley et al. (2008) and Oduwole et al. (2009) reported that in 43% of UKA-to-TKA revision surgery, a long femoral or tibial stem, metal augments, or bone grafting was needed. Proper preoperative planning can make revision less difficult (Saragaglia et al. 2009), and computer-assisted surgery peroperatively may be of value (Confalonieri et al. 2010). Recently, a patient-specific alignment guide technique, Signature Personalized Patient Care (SPPC; Biomet, Inc., Warsaw, IN), was developed based on MRI imaging of the knee. A preoperative plan is made in which problems to be expected can be anticipated. Next, a template is formed that can be used as an alignment guide during the operation in order to improve correct positioning of the newly implanted TKA. We describe a new application of this templating technique for revision of UKA to TKA, and the operative results of the first 10 patients treated.

Patients and methods

SPPC was initially developed for primary TKA. The technique uses MRI imaging to create templates for both the tibia and the femur that can be used as alignment guides intraoperatively (Lombardi et al. 2008). Since there is a prosthesis in situ in cases of revision, MRI imaging cannot be used. CT imaging can replace MRI imaging in these cases. We performed preoperative low-dose CT imaging of the leg 6 weeks before surgery according to a standard scanning protocol to determine the mechanical axis of the leg and the anatomy of the knee. Software (Materialise NV, Leuven, Belgium) was used to create virtual 3-dimensional models of the femur and tibia using this CT scan. The same software was used to determine appropriate implant size and optimal positioning of the prosthesis (Vanguard Complete Knee System; Biomet) for each patient individually. Calculations were performed to minimize bone loss during the revision. The position of the prosthesis was further determined to obtain a neutral mechanical axis of the leg and a neutral position of both femoral and tibial components to the mechanical axis of the bone in the frontal plane. In the sagittal plane, posterior slope of the tibial component and flexion of the femoral component were set at 3°. Calculations were performed to avoid notching of the femoral component. The distal femoral cut was set at 9 mm proximal to the most distal femoral point. Femoral component rotation was set parallel to the transepicondylar axis in the coronal plane and tibial component rotation was determined using the medial third of the tibial tuberosity and the posterior sulcus as a reference point. Component sizing was determined by measuring the anteroposterior dimension of the distal femur and the contour of the proximal tibia. A digital virtual plan of the operation to be performed was sent to the surgeon (Figure 1). The surgeon could adjust the digital plan satisfactorily by changing implant size and position, rotation, translation, flexion, and resection level. Thereafter, the patient-specific disposable guides were manufactured from polyamide. These guides have one single fitting position specific to the anatomy of the patient’s knee as determined by CT scan (Figure 2). In all patients, the incision was made using the old scar with extensions to proximal and distal. A medial parapatellar arthrotomy was performed and standard exposure of the femur and tibia was carried out with patellar eversion. The fixation of the prosthesis was checked. Soft tissue that interfered with placement of the guides was removed.

Figure 1.

Digital virtual plan of the operation to be performed, and actual postoperative radiographs.

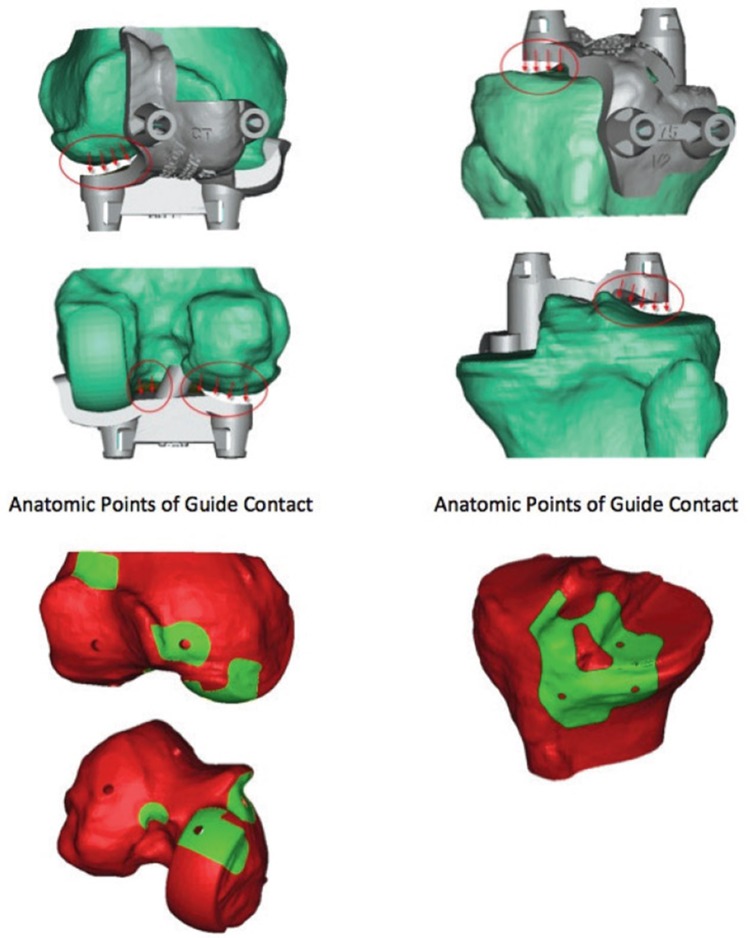

Figure 2.

Single-way fitting position of guides on the patient’s individual anatomy.

The guide was created to fit on both UKA and native bony reference points since cartilage cannot be seen by CT scanning. Thus, there was no contact between either the cartilage of the lateral femoral condyle or the lateral tibial plateau and the guide (Figure 3). The femoral guide was placed in the fit position and fixed to the bone with 3 pins. The fourth pin could not be inserted due to the prosthesis still being in situ. The guide was taken off and the femoral component of the prosthesis was carefully removed using osteotomes to break the cement-prosthesis interface. Next, the cement was removed with a rongeur and the guide was replaced on the distal femur according to the position of the three predrilled holes; thereafter, the fourth pinhole was drilled (Figure 4). The guide was removed and the pins were used to position the femoral cutting blocks to make bone resections for the new TKA (Figure 5). The same procedure was performed on the tibial side. Further operative procedure was standard for TKA and included application of a tourniquet before rinsing the knee extensively with a pulse lavage system. Patellar resurfacing was not performed in any of the patients. Ligament balancing was performed as needed. All procedures were performed by one knee surgeon (NK) with extensive experience in performing primary Oxford UKA, Signature and conventional Vanguard TKA, and conventional UKA-to-TKA revision surgery.

Figure 3.

Illustration showing that there was no contact between either the cartilage of the lateral femoral condyle or the lateral tibial plateau and the guide.

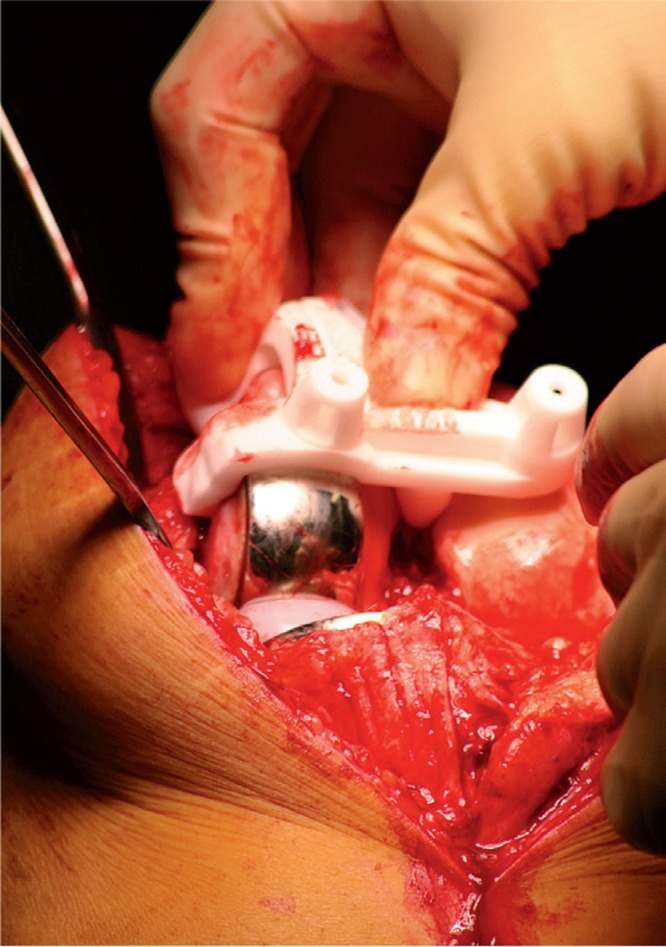

Figure 4.

Repositioning of the guide after removal of the prosthesis using the three predrilled holes and insertion of the fourth pin.

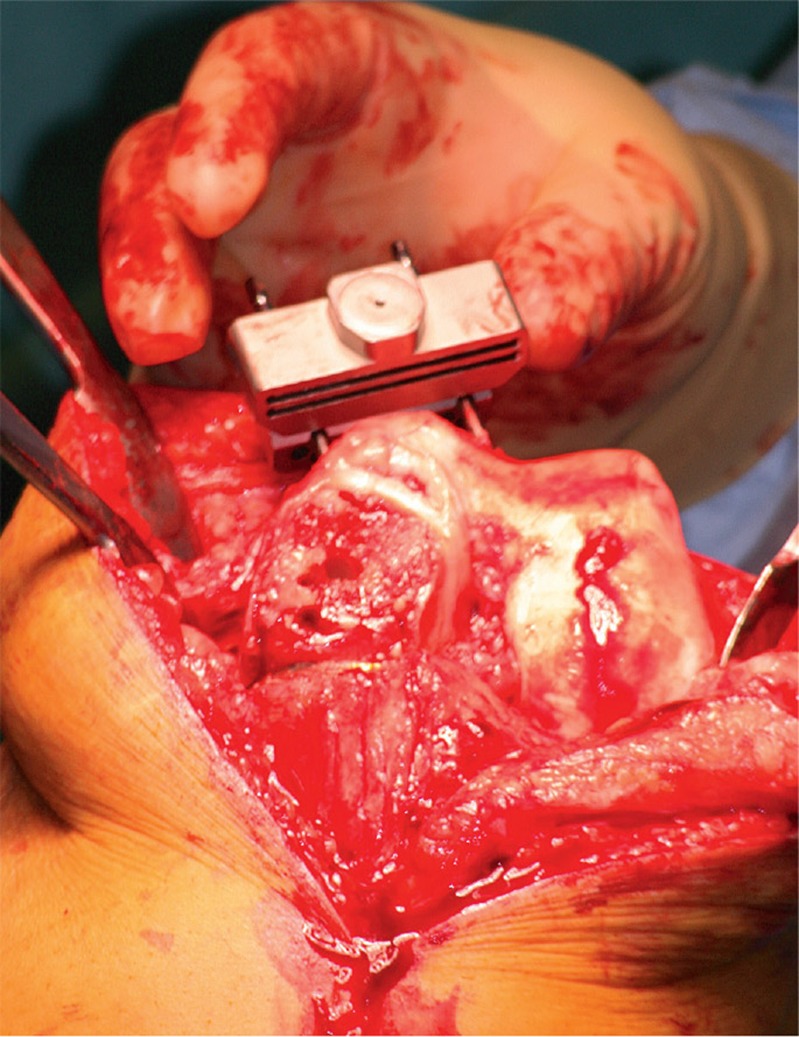

Figure 5.

Pins were used to position the femoral cutting blocks to make bone resections for the new TKA.

10 consecutive patients (6 females) with an indication for UKA-to-TKA revision surgery were included in the study. 4 right knees and 6 left knees were operated on. Mean age at the time of primary surgery was 57 (39–69) years and the mean time between primary and revision surgery was 37 (7–79) months. The reason for revision was pain of unknown origin in 4 cases, loosening of the tibial component in 3 cases, loosening of the femoral component in 1 case, femoral component impingement in 1 case, and progression of osteoarthritis in 1 case. Blood loss and operation time were obtained from the operative records, completed by an independent operating room nurse. A function test was performed 6 weeks postoperatively and measurements were made using a goniometer. Radiographic measurements were performed electronically on standing long-leg radiographs and standard lateral radiographs using digital calculations. Hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle and varus/valgus position of the individual prosthesis components were assessed on the long-leg radiographs. Flexion/extension of the femoral component and anterior/posterior slope of the tibial component were measured on the lateral radiographs. Radiographic assessment was performed twice by 3 assessors (BB, MS, and BK). The attending surgeon (NK) was not involved in these assessments. The mean value obtained from the measurements was used as our definitive value. The reliability of the angles measured was determined by calculating intra-assessor and inter-assessor reliabilities using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs). ICC can range between 0 and 1. An ICC greater than 0.75 indicates good to excellent reliability. Intra-rater reliabilities for each assessor and inter-rater reliabilities were good (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intra-assessor and inter-assessor intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) per measured angle

| Intra-rater (author BB) |

Intra-rater (author MS) |

Intra-rater (author BK) |

Inter-rater | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HKA angle | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Tibial component AP angle | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.81 |

| Femoral component AP angle | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.85 |

| Tibial component sagittal angle | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.77 |

| Femoral component sagittal angle | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.83 |

Ethics

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. All patients were informed and consented to providing data for anonymous use.

Results

All individual guides fitted well on all patients. No excessive bone loss was observed and only 1 patient needed a long-stem tibial component with metal augmentation. In this case, only 2 lateral pins could be inserted in the tibia using the guide. The third, medial anterior pin could not be inserted into the bone since the prosthesis was in a distal position. This resulted in inadequate and unstable positioning of the guide. At this stage, use of the guide was abandoned and a conversion to standard intramedullary outlining was performed. This was to be expected since the preoperative planning had already revealed the situation (Figure 6). No further complications occurred.

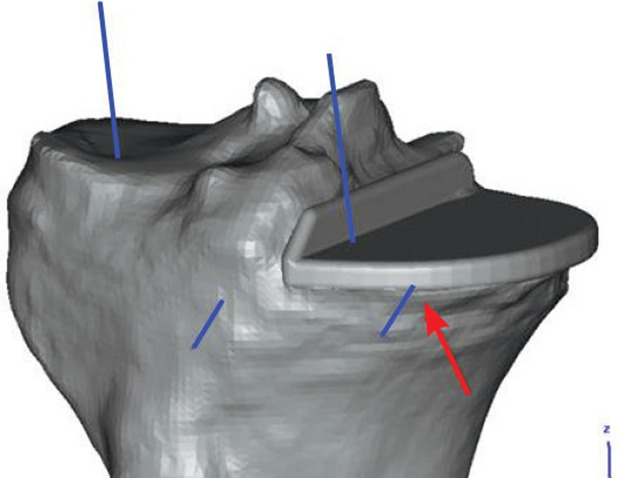

Figure 6.

Preoperative planning shows that the medial anterior pin (blue line marked and red arrow) cannot be drilled into bone in a stable way.

Mean operation time was 83 (59–120) min. The mean estimated blood loss was 270 (150–500) mL.

A mean HKA angle of 2° varus was observed; the tibial component showed a mean of 1° valgus and the femoral component showed a mean of 3° varus. In the sagital view, the mean posterior slope of the tibial component was 1° and the mean femoral component flexion was 5° (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle, varus/valgus position of the tibial and femoral components (tibia AP and femur AP), and flexion/extension of the tibial and femoral components (tibia sagittal and femur sagittal). Positive values indicate varus, posterior tibial slope, and femoral component flexion. Negative values indicate valgus, anterior tibial slope, and femoral component extension. Outliers are defined as being more than 3° from the desired position and numbers of outliers are shown depending on the extent of being more than 3° from the ideal position

| Mean (SD) | Range | Desired | Outlier 1 | Outlier 2 | Outlier total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HKA angle | 2 (1.7) | 0 to 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Tibial component AP angle | –1 (1.1) | –2 to 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Femoral component AP angle | 3 (0.9) | 1 to 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Tibial component sagittal angle | 1 (2.5) | –2 to 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Femoral component sagittal angle | 5 (2.7) | –1 to 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

All patients were mobilized on day 1 postoperatively in the presence of a physiotherapist, and direct full weight bearing was allowed in all cases. At 6 weeks, all patients had good stability of the knee with less than 5 mm of anteroposterior motion in all cases and a mediolateral slack that was also less than 5 mm, except for 2 patients in which the mediolateral slack was between 5 and 10 mm. The mean postoperative flexion was 111° (90–135). All but 2 patients were able to extend the knee fully. Of these 2, one had an extension deficit of 5° and the other had a deficit of 10°.

Discussion

Depending on the reason for which UKA revision is needed, a single component can be revised, revision to a new UKA can be performed, or revision to a TKA may be obligatory (Kerens and Kort 2012, Pearse et al. 2010). Revision of UKA to TKA shows better results than revision of UKA to UKA (Pearse et al. 2010). Some authors have reported that the revision procedure of UKA to TKA is technically not more difficult than revision from TKA to TKA (McAuley et al. 2001, Johnson et al. 2007, Saldanha et al. 2007). Others have reported that revision of UKA to TKA is a technically demanding procedure with possible bone loss (Chatain et al. 2004, Springer et al. 2006). Preoperative planning and computer-assisted surgery can help reduce peroperative problems (Confalonieri et al. 2010). We wanted to create patient-specific single-way fitting guides for intraoperative use that are created preoperatively from CT imaging of the patient’s leg. Planning of the operation was done using a virtual overview of the patient-specific anatomy with the prosthesis in situ. With this technique, the need for augmentation or for a long-stem prosthesis can be predicted accurately prior to surgery.

Since the guide is specific for the anatomy of the patient with the UKA prosthesis in situ and also for the bony anatomy of the patient without the UKA prosthesis in situ, the technique can be used with the prosthesis in a stable position in situ but also when the prosthesis is loose or when it has been removed.

The implant position was good in all cases, and no joint line restoration problems were observed.

Improvement of the procedure would include the formation of guides with the possibility of more distal pin positioning in cases of medial tibial bone loss, when observed during the preoperative planning. This is a UKA revision-specific change in design and instrumentation that should be performed in the future to make this technique successful in all cases.

For primary TKA, SPPC uses MRI imaging to create single-way fitting guides. With the metal of a UKA in situ, MRI scanning is not possible. Low-resolution CT imaging can replace MRI imaging for this purpose. One side effect, however, is exposure of the patient’s leg to a mean radiation of 5.7 mSv. This amount of radiation is slightly less than that of a single CT scan of the abdomen or cerebrum. The costs of creating the guides are minor and are, in our opinion, compensated for by the fact that more thorough preoperative planning can be performed, which may reduce operating time and logistical problems.

We believe that this new commercially available technique can help to make UKA-to-TKA revision surgery less technically demanding. It appears to be a reliable tool, but we studied a limited number of patients. Larger patient series will be needed to confirm our preliminary results. Fine-tuning of the technique is also needed for cases in which there is more loss of bone stock preoperatively.

Acknowledgments

BK and MS: collected and analyzed data, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. BB: collected and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. NK: operated on all patients and revised the manuscript.

One author (NK) lectures on the SPPC operation technique for Biomet. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Chatain F, Richard A, Deschamps G, Chambat P, Neyret P. Revision total knee arthroplasty after unicompartmental femorotibial prosthesis: 54 cases. Rev Chir Orthop Rep Appar Mot. 2004;90(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(04)70006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confalonieri N, Manzotti A, Chemello C, Cerveri P. Computer-assisted revision of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):52–7. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100510-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley TE, Gioe TJ, Sinner P, Mehle S. Registry outcomes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty revisions. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(7):1666–70. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0279-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Jones P, Newman JH. The Survivorship and results of total knee replacements converted from unicompartmental knee replacements. The Knee. 2007;14(2):154–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerens B, Kort NP. Overstuffed medial compartment after mobile bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscop. 2012;19(6):952–4. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi AV, Jr, Berend KR, Adams JB. Patient-specific approach in total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2008;31(9):927–30. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080901-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley JP, Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Revision of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2001;(392):279–82. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oduwole KO, Sayana MK, Onayemi F, McCarthy T, O’Byrne J. Analysis of revision procedures for failed unicondylar knee replacement. Irish J Med Science. 2009;179(3):361–4. doi: 10.1007/s11845-009-0454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse AJ, Hooper GJ, Rothwell A, Frampton C. Survival and functional outcome after revision of a unicompartmental to a total knee replacement: The New Zealand National Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(4):508–12. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B4.22659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha KA, Keys GW, Svard UC, White SH, Rao C. Revision of Oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty–Results of a multicentre study. The Knee. 2007;14(4):275–9. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragaglia D, Estour G, Nemer C, Colle PE. Revision of 33 unicompartmental knee prostheses using total knee arthroplasty: Strategy and results. Int Orthop. 2009;33(4):969–74. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0585-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer BD, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to TKA. Clin Orthop. 2006;(446):214–20. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000214431.19033.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi G, Strover AE. Early complications of unicompartmental knee replacement: The Droitwich Experience. The Knee. 2004;11(5):389–94. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]