Abstract

Background and purpose

Periprosthetic fracture is a devastating complication of total knee replacement (TKR). Most published studies have not comprehensively assessed clinical and demographic predictors. We wanted to determine the incidence and predictors of postoperative periprosthetic fracture after primary and revision TKR.

Patients and methods

We used prospectively collected data in the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry on all patients who underwent primary or revision TKR at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, from 1989 through 2008. We assessed incidence of postoperative periprosthetic fractures and modifiable (comorbidity, body mass index) and unmodifiable factors (age, sex, operative diagnosis, ASA class, previous cardiac disease, and previous thromboembolic disease) as predictors of postoperative periprosthetic fractures. We used multivariable-adjusted Cox regression analyses separately for primary and revision TKR.

Results

12,914 patients underwent 17,633 primary TKRs and 3,286 patients underwent 4,090 revision TKRs during the period 1989–2008. 1.1% of patients (188/17,633) after primary TKR and 2.5% of patients (104/4,090) after revision TKR sustained a postoperative periprosthetic fracture on or after postoperative day 1. Older age was associated with lower risk of periprosthetic fractures after primary TKR (p < 0.001). Compared to ≤ 60 years, risk was lower for ages 61–70 years (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.5, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.3–0.7)) and 71–80 years (HR = 0.6, CI: 0.4–0.8), but not for age > 80 years (HR = 0.9, CI: 0.5–1.6). In revision TKR cohort, a diagnosis of non-union (HR = 4.9, CI: 1.2–20), infection (HR = 2.9, CI: 1.3–6.4) or previous surgery with components removed (HR = 2.1, CI: 1.3–3.4) increased the risk of postoperative periprosthetic fracture, compared to a diagnosis of loosening/wear/osteolysis.

Interpretation

We identified significant risk factors for periprosthetic fracture after primary and revision TKR. Patients with these risk factors can be informed by their surgeons of increased risk of this uncommon, but serious complication of TKR.

Periprosthetic fracture is an uncommon but significant complication of total knee replacement (TKR). A wide range in incidence of fracture after TKR—from 0.3% to 2.5%—has been reported (Aaron and Scott 1987, Merkel and Johnson 1986, Rorabeck and Taylor 1999). The consequences of periprosthetic fracture after a TKR in the elderly are devastating, including increased morbidity and mortality and the need for revision surgery (Bhattacharyya et al. 2007, Figgie et al. 1990, Meek et al. 2011). Most studies that have assessed the incidence of periprosthetic fractures were performed 20–30 years ago (Delport et al. 1984, Culp et al. 1987, Figgie et al. 1990). Due to changing demographics of patients receiving TKR (Crowninshield et al. 2006, Khatod et al. 2008), the risk of periprosthetic fracture may be changing. The indications of TKR have expanded dramatically in the last 2 decades to include much younger (Khatod et al. 2008) and older patients (Melzer et al. 2003), both of whom may have a higher risk of having periprosthetic fractures. More recent estimates are needed to better inform patients and surgeons about this risk.

Most of the previous studies that examined risk factors for periprosthetic fractures after TKR did not perform multivariable-adjusted statistical analyses, and they had small number of cases and relatively short duration of follow-up. Several risk factors for periprosthetic fractures were identified, including osteoporosis (Merkel and Johnson 1986, Beals and Tower 1996), inflammatory arthritis (Merkel and Johnson 1986, Lindahl et al. 2006 a, b), corticosteroid use (Porsch et al. 1996), older age (Meek et al. 2011), female gender (Bethea et al. 1982, Beals and Tower 1996, Meek et al. 2011), and previous revision arthroplasty (Merkel and Johnson 1986, Lindahl et al. 2006a, Meek et al. 2011, ). Recent reviews have summarized these findings (Rorabeck and Taylor 1999, McGraw and Kumar 2010). Most previous studies focused on primary TKRs, and therefore little is known about fractures after revision TKRs. These studies did not examine modifiable factors such as body mass index (BMI) and comorbidity.

The objective of this study was to: (1) provide estimates of periprosthetic fracture after primary and revision TKR, and (2) to determine whether patient demographic characteristics (age and sex) and clinical characteristics (such as comorbidity and BMI) were independently associated with the risk of periprosthetic fracture.

Patients and methods

Selection of study cohort

We used data prospectively collected in a large institutional registry to perform analyses of periprosthetic fractures after primary and revision TKR. The Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry has prospectively collected preoperative and postoperative follow-up data on all patients who underwent arthroplasty at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, since the first hip and knee arthroplasty were performed in 1969 and 1971, respectively (Berry et al. 1997). All patients are prospectively followed with clinical follow-up visits, and in those who do not return, with mailed questionnaires and telephone interviews administered by trained, dedicated Total Joint Registry staff. The data are stored electronically in a database. Complications including but not limited to fracture, infection, surgical procedures, and mortality are registered. Medical records including radiographs and operative reports are obtained from outside institutions to confirm complications such as fractures. From this registry, we selected patients who underwent primary or revision TKR between 1989 and 2008. This time period was chosen to provide a large enough sample, to be more representative of recent data, and to allow inclusion of important variables such as BMI and ASA class in the analyses, which were available in electronic datasets from 1989. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

Study outcome and predictors

The study outcome was the occurrence of postoperative periprosthetic fracture from postoperative day 1 or later in patients with primary or revision TKR. This excluded intraoperative fractures or fractures on the day of surgery, which are difficult to differentiate from each other definitively, since the exact time of each fracture is not captured in the registry. Intraoperative fractures were not of interest in this study.

We considered several important potential risk factors for postoperative periprosthetic fractures after primary or revision TKR. The demographic characteristics included sex and age, categorized as previously described (≤ 60, 61–70, 71–80 and > 80 years) (Singh et al. 2008, 2011, Singh and Lewallen 2009). Clinical variables included BMI, comorbidity assessed with the Deyo-Charlson index (Deyo et al. 1992), and the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status score (Dripps et al. 1961). BMI was categorized as < 25, 25–29.9 (overweight), 30–39.9 (obese), or ≥ 40 (morbidly obese), as previously described (Singh et al. 2011) and as in the WHO classification (WHO 2000). Comorbidity was assessed with the Deyo-Charlson index, a validated measure of comorbidity consisting of a weighted scale of 17 comorbidities (including cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, renal disease, hepatic disease, diabetes, cancer, hemiplegia, and HIV), expressed as a summative score (Charlson et al. 1987 a, b). ASA score, categorized as class I–II or III–IV, is a validated measure of perioperative mortality and immediate postoperative morbidity (Dripps et al. 1961, Weaver et al. 2003). Implant fixation was categorized as cemented implant (including hybrid) or uncemented implant. Operative diagnosis was categorized as follows: (a) osteoarthritis, rheumatoid/inflammatory arthritis, avascular necrosis, or other, for primary TKR; and (b) loosening/wear/osteolysis, dislocation/bone fracture or prosthesis fracture/instability/non-union (with non-union being defined as non-united fractures, such as non-union of a femoral head fracture, proximal or distal femoral fracture, or patellar fracture, including periprosthetic fractures), failed previous arthroplasty with components removed/infection, for revision TKR. The latter group included patients with previous fractures with components removed with failed previous internal fixation or previous athrodesis and patients with patellectomy and osteotomy or with infection.

Statistics

We performed separate analyses for primary and revision TKR. Using univariate Cox regression analyses, all predictor variables were assessed for association with the hazard of periprosthetic fracture after TKR. All variables significantly associated in univariate regression (p < 0.05) were entered into a backward-selection multivariable-adjusted Cox regression model. The proportional hazard assumption held true in the multivariable models for primary and revision TKR. The models accounted for correlated data due to bilateral TKR in the same patient. The models account for correlated joints within the same patient. We used the covsandwich (aggregate) option using the id statement to account for correlated joints (Lee et al. 1992). Censoring was at the occurrence of the postoperative periprosthetic fracture or death, or loss to follow-up. Hazard ratios (HRs) are given with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also performed survival analyses using Kaplan-Meier curves, for primary and revision TKR cohorts separately.

Results

Characteristics of study cohort

Between 1989 and 2008, 12,914 patients underwent 17,633 primary TKRs at the Mayo Clinic. Mean age was 68 years; 9% of the patients were older than 80 years and 81% were older than 60 years. 55% of the patients were women. 27% had bilateral TKR and mean follow-up time was 6.3 years (Table 1). 44% were ASA class 3 or higher and 21% had a Deyo-Charlson index of 3 or more. Osteoarthritis was the underlying diagnosis in 93% of patients, and 91% had cemented or hybrid implant fixation.

Table 1.

Demographic features of study cohort as mean (SD) or n (%), unless specified otherwise

| Primary TKA | Revision TKA | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 17,633) | (n = 4,090) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| or n (%) | or n (%) | |

| Mean follow-up, years (SD) | 6.3 (4.7) | 5.1 (4.2) |

| Female | 9,781 (55%) | 2,084 (51%) |

| Bilateral | 4,719 (27%) | 804 (20%) |

| Mean age at surgery, years (SD) | 68.4 (10.0) | 67.9 (11.3) |

| Age category | ||

| ≤ 60 years | 3,352 (19%) | 915 (22.4%) |

| 61–70 years | 6,206 (35.2%) | 1,286 (31.4%) |

| 71–80 years | 6,493 (36.8%) | 1,476 (36.1%) |

| >80 years | 1,582 (9%) | 413 (10.1%) |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 (SD) | 31.2 (6.2) | 31.1 (6.5) |

| BMI category, kg/m2 | ||

| Missing | 67 (0.4%) | 36 (0.9%) |

| Normal, < 25.0 | 2,362 (13.4%) | 584 (14.4%) |

| Overweight, 25–29.9 | 5,961 (33.9%) | 1,363 (33.6%) |

| Obese, 30–39.9 | 7,710 (43.9%) | 1,731 (42.7%) |

| Morbidly obese, ≥ 40.0 | 1,533 (8.7%) | 376 (9.3%) |

| ASA class a | ||

| 1 | 291 (1.7%) | 50 (1.2%) |

| 2 | 9,614 (54.7%) | 1,869 (45.8%) |

| 3 | 7,544 (42.9%) | 2,098 (51.4%) |

| 4 | 117 (0.7%) | 61 (1.5%) |

| Mean Deyo-Charlson index (SD) | 1.5 (2.2) | 1.3 (2.1) |

| Deyo-Charlson index | ||

| 0 | 7,985 (45.3%) | 2,086 (51%) |

| 1 | 3,598 (20.4%) | 836 (20.4%) |

| 2 | 2,291 (13%) | 470 (11.5%) |

| 3+ | 3,759 (21.3%) | 698 (17.1%) |

| Previous cardiac event | ||

| No | 14,404 (81.7%) | 3,490 (85.3%) |

| Yes | 3,229 (18.3%) | 600 (14.7%) |

| Previous thromboembolic event | ||

| No | 16,869 (95.7%) | 3,873 (94.7%) |

| Yes | 764 (4.3%) | 217 (5.3%) |

| Operative diagnosis (primary TKR) | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 16,372 (92.8%) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 657 (3.7%) | |

| Avascular necrosis | 152 (0.8%) | |

| Other b | 604 (3.4%) | |

| Operative diagnosis (revision TKR) | ||

| Failure: loose/wear/osteolysis | 2,154 (52.7%) | |

| Failure: previous surgery with | ||

| components removed | 801 (19.6%) | |

| Failure: fracture, dislocation | 877 (21.4%) | |

| Failure: non-union | 27 (0.7%) | |

| Failure: infection | 228 (5.6%) | |

| Implant fixation | Not applicable | |

| Uncemented | 1,555 (8.8%) | |

| Cemented or hybrid* | 16,078 (91.2%) |

a American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score was missing in 67 (0.4%) of primary TKR patients and 12 (0.3%) of revision TKR patients

b Other diagnoses for primary TKA included: genu varum, genu valgum, hemophilia, Paget’s disease, failed previous disease including arthrodesis, failed previous osteotomy, failed previous patellectomy, Chacot arthropathy, chondromalacia, pigmented villonodular synovitis; data on operative diagnosis were missing for 3 patients with revision TKR.

The revision study cohort consisted of 3,286 patients who underwent 4,090 revision TKRs at the Mayo Clinic from 1989 through 2008. Mean age was also 68 years, 51% were women, 20% had bilateral TKR, and mean follow-up time was 5.1 years (Table 1). 10% of patients were older than 80 years and 78% were older than 60 years. ASA was class I–II in 47%; 12% had a Deyo-Charlson index of 2 and 17% had a Deyo-Charlson index of 3 or more. The most frequent underlying diagnosis was loosening, wear, or osteolysis (53%), followed by fracture/dislocation (21%) and failed previous surgery with components removed (20%).

Cumulative incidence of postoperative periprosthetic fracture

The cumulative incidence of postoperative periprosthetic fracture on or after postoperative day 1 after primary TKR was 1.1% (188/17,633 patients) and it was 2.5% after revision TKR (104/4,090 patients). 74% of fractures occurred 1 year or more after primary and revision TKR (Appendix 1).

Risk factors for postoperative periprosthetic fractures after primary TKR

Age was the only factor that was significantly associated with higher risk of postoperative periprosthetic fracture after primary TKR in univariate analysis (Table 2). Higher Deyo-Charlson comorbidity class showed a non-significant association with fracture after primary TKR.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable-adjusted risk of periprosthetic fracture following primary total knee arthroplasty

| Total | Periprosthetic fractures | Univariate hazard | Multivariable a model 1 hazard | Multivariable b model 2 hazard | Multivariable c model 3 hazard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n = 17,633) | (n = 188) | ratio (95% CI) | ratio (95% CI) | ratio (95% CI) | ratio (95% CI) |

| Sex | p = 0.2 | p = 0.2 | ||||

| Male | 7,852 | 74 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Female | 9,781 | 114 (1%) | 1.23 (0.91–1.64) | 1.24 (0.92–1.68) | ||

| Age category | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.002 | ||

| ≤ 60 | 3,352 | 52 (2%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 61–70 | 6,206 | 59 (1%) | 0.52 (0.36–0.76) | 0.51 (0.35–0.74) | 0.52 (0.36–0.76) | 0.52 (0.36–0.77) |

| 71–80 | 6,493 | 58 (1%) | 0.56 (0.38–0.81) | 0.55 (0.38–0.80) | 0.55 (0.37–0.80) | 0.54 (0.36–0.80) |

| > 80 | 1,582 | 19 (1%) | 0.97 (0.57–1.65) | 0.97 (0.57–1.64) | 0.94 (0.55–1.61) | 0.90 (0.52–1.58) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | p = 0.4 | p = 0.5 | ||||

| Normal, < 25.0 | 2,362 | 29 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Overweight, 25–29.9 | 5,961 | 75 (1%) | 0.77 (0.50–1.18) | 1.09 (0.70–1.68) | ||

| Obese, 30–39.9 | 7,710 | 71 (1%) | 0.94 (0.49–1.81) | 0.83 (0.54–1.30) | ||

| Morbidly obese, ≥ 40.0 | 1,533 | 13 (1%) | 0.99 (0.64–1.51) | 0.87 (0.44–1.71) | ||

| Deyo-Charlson index | p = 0.06 | p = 0.05 | p = 0.04 | |||

| 0 | 7,985 | 75 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 1 | 3,598 | 42 (1%) | 1.27 (0.87–1.86) | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | 1.22 (0.82–1.81) | |

| 2 | 2,291 | 25 (1%) | 1.35 (0.86–2.13) | 1.39 (0.88–2.19) | 1.42 (0.90–2.26) | |

| 3+ | 3,759 | 46 (1%) | 1.66 (1.15–2.40) | 1.68 (1.16–2.44) | 1.75 (1.18–2.59) | |

| Previous cardiac event | p = 0.2 | p = 0.07 | ||||

| No | 14,404 | 166 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 3,229 | 22 (1%) | 0.76 (0.49–1.19) | 0.65 (0.40–1.04) | ||

| Previous thromboembolism | p = 0.6 | p = 0.6 | ||||

| No | 16,869 | 181 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 764 | 7 (1%) | 1.21 (0.57–2.58) | 1.20 (0.56–2.57) | ||

| Operative diagnosis | p = 0.2 | p = 0.2 | p = 0.3 | |||

| Osteoarthritis | 16,372 | 159 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 657 | 13 (2%) | 1.13 (0.28–4.57) | 1.16 (0.64–2.11) | 1.01 (0.55–1.87) | |

| Avascular necrosis | 152 | 2 (1%) | 1.73 (0.99–3.01) | – | – | |

| Other | 452 | 14 (3%) | 1.51 (0.85–2.65) | 1.57 (0.94–2.65) | 1.55 (0.92–2.61) | |

| Implant fixation | p = 0.3 | p = 0.6 | ||||

| Uncemented | 1555 | 14 (1%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Cemented or hybrid | 16,078 | 174 (1%) | 0.76 (0.44–1.31) | 0.87 (0.50–1.51) | ||

| ASA class | p = 0.5 | p = 0.6 | ||||

| 1 | 291 | 5 (2%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 2 | 9,614 | 97 (1%) | 0.64 (0.26–1.58) | 0.75 (0.30–1.86) | ||

| 3 | 7,544 | 83 (1%) | 0.79 (0.32–1.94) | 0.93 (0.36–2.37) | ||

| 4 | 117 | 1 (1%) | 0.66 (0.08–5.68) | 0.80 (0.09–6.99) |

a Multivariable model 1 was a Cox regression model that considered all significant variables from the univariate analyses with a p-value of < 0.05–and retained only those significantly associated in the multivariable model by using a backward-selection process; the c-statistic of the multivariable model was 0.58.

b Multivariable model 2 was a Cox regression model obtained by retaining all variables from the univariate analyses with a p-value of < 0.20 and forcing all of them in the model; the c-statistic of the multivariable model was 0.61.

c Multivariable model 3 was a Cox regression model obtained by retaining all variables from the univariate analyses regardless of p-value and forcing all of them in the model; the c-statistic of the multivariable model was 0.62.

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI: confidence interval; ref: reference category.

In multivariable-adjusted analyses, only age was significantly associated with risk of postoperative periprosthetic fracture after primary TKR. Age categories 61–70 and 71–80 were both associated with a 40–50% lower risk compared to age 60 years or younger, while age > 80 years was not statistically significantly different from age ≤ 60 years in this respect (Table 2). We performed additional post-hoc testing of whether age > 80 years was associated with higher fracture risk than ages 61–70 and 71–80; we obtained hazard ratios of 1.9 (CI: 1.1–3.1) and 1.7 (CI: 1.0–2.9), which were both statistically significant with p-values of 0.02 and 0.04, respectively. Sensitivity analysis that adjusted for length of FU by testing the term “age*length of follow-up” revealed that length of FU did not significantly affect the significant relationship between age and postoperative periprosthetic fractures after primary TKR.

Risk factors for postoperative periprosthetic fracture after revision TKR

In univariate analyses, we found that operative diagnosis and higher comorbidity, assessed with Deyo-Charlson index, were significantly associated with the risk of postoperative periprosthetic fracture (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard of periprosthetic fracture after revision total knee arthroplasty

| Total | Periprosthetic fractures | Univariate hazard | Multivariable a model 1 hazard | Multivariable b model 2 hazard | Multivariable c model 3 hazard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n =4,090) | (n = 104) | ratio (95% CI) | ratio (95% CI) | ratio (95% CI) | ratio (95% CI) |

| Sex | p= 0.09 | p = 0.06 | p = 0.06 | |||

| Male | 2,006 | 42 (2%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Female | 2,084 | 62 (3%) | 1.40 (0.9–2.07) | 1.47 (0.98–2.21) | 1.48 (0.99–2.22) | |

| Age category | p = 0.3 | p = 0.3 | ||||

| ≤60 | 915 | 27 (3%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 61-70 | 1,286 | 38 (3%) | 0.84 (0.51–1.38) | 0.82 (0.49–1.36) | ||

| 71-80 | 1,476 | 34 (2%) | 0.68 (0.41–1.14) | 0.68 (0.40–1.16) | ||

| >80 | 413 | 5 (1%) | 0.44 (0.17–1.15) | 0.44 (0.16–1.18) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | p = 0.1 | p = 0.2 | p = 0.4 | |||

| Normal, < 25.0 | 584 | 16 (3%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Overweight, 25-–29.9 | 1,363 | 35 (3%) | 0.89 (0.50–1.60) | 1.04 (0.58–1.87) | 1.05 (0.58–1.91) | |

| Obese, 30–39.9 | 1,731 | 39 (2%) | 1.93 (0.92–4.02) | 1.99 (0.95–4.19) | 1.81 (0.85–3.86) | |

| Morbidly obese, ≥4 0.0 | 376 | 13 (3%) | 0.97 (0.54–1.76) | 1.14 (0.62–2.08) | 1.20 (0.65–2.22) | |

| Deyo-Charlson index | p = 0.05 | p = 0.08 | p = 0.08 | |||

| 0 | 2,086 | 46 (2%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 1 | 836 | 19 (2%) | 1.07 (0.63–1.83) | 1.07 (0.62–1.83) | 1.08 (0.62–1.87) | |

| 2 | 470 | 15 (3%) | 1.56 (0.87–2.80) | 1.53 (0.85–2.75) | 1.56 (0.85–2.85) | |

| 3+ | 698 | 24 (3%) | 1.94 (1.18–3.18) | 1.87 (1.13–3.12) | 1.92 (1.13–3.26) | |

| Previous cardiac event | p = 0.9 | p = 0.5 | ||||

| No | 3,490 | 91 (3%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 600 | 13 (2%) | 1.05 (0.59–1.88) | 0.82 (0.43–1.56) | ||

| Previous thromboembolism | p = 0.08 | p = 0.3 | p = 0.3 | |||

| No | 3,873 | 97 (3%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 217 | 7 (3%) | 1.97 (0.91–4.26) | 1.50 (0.69–3.29) | 1.51 (0.69–3.33) | |

| Operative diagnosis (revision) | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.003 | p = 0.004 | ||

| Failure: Loose/wear/osteolysis | 2,154 | 48 (2%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Failure: Previous surgery | 801 | 29 (4%) | 2.12 (1.34–3.37) | 2.12 (1.34–3.37) | 2.14 (1.33–3.42) | 2.07 (1.29–3.32) |

| Failure: Fracture/dislocation | 877 | 18 (2%) | 1.14 (0.66–1.96) | 1.14 (0.66–1.96) | 1.14 (0.66–1.98) | 1.13 (0.66–1.96) |

| Failure: Nonunion | 27 | 2 (7%) | 4.82 (1.17–19.9) | 4.82 (1.17–19.9) | 4.54 (1.09–18.9) | 4.46 (1.06–18.7) |

| Failure: Infection | 228 | 7 (3%) | 2.88 (1.30–6.40) | 2.88 (1.30–6.40) | 2.67 (1.19–6.00) | 2.73 (1.21–6.16) |

| ASA class | p = 0.4 | p = 0.7 | ||||

| 1 | 50 | 2 (4%) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 2 | 1,869 | 41 (2%) | 0.63 (0.15–2.62) | 0.72 (0.17–3.05) | ||

| 3 | 2,098 | 60 (3%) | 0.91 (0.22–3.73) | 0.91 (0.21–3.87) | ||

| 4 | 61 | 1 (2%) | 0.82 (0.07–9.06) | 0.68 (0.06–7.89) |

a Multivariable model 1 was a Cox regression model that considered all significant variables from the univariate analyses with p-value <0.05 and retained only those significantly associated in the multivariable model by using a backward selection process; the c-statistic of the multivariable model was 0.60

b Multivariable model 2 was a Cox regression model obtained by retaining all variables from the univariate analyses with p-value <0.20 and forcing all of them in the model; the c-statistic of the multivariable model was 0.63

c Multivariable model 3 was a Cox regression model obtained by retaining all variables from the univariate analyses regardless of p-value and forcing all of them in the model; the c-statistic of the multivariable model was 0.64

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI: confidence interval; ref: reference category.

In the multivariable-adjusted analyses, we found that diagnosis was significantly associated with the risk of postoperative periprosthetic fracture after primary TKR (Table 3). Diagnoses of non-union, infection or previous surgery with components removed were associated with a 4.8-, 2.9- and 2-fold higher risk of fracture, respectively, compared to a diagnosis of loosening, wear, or osteolysis.

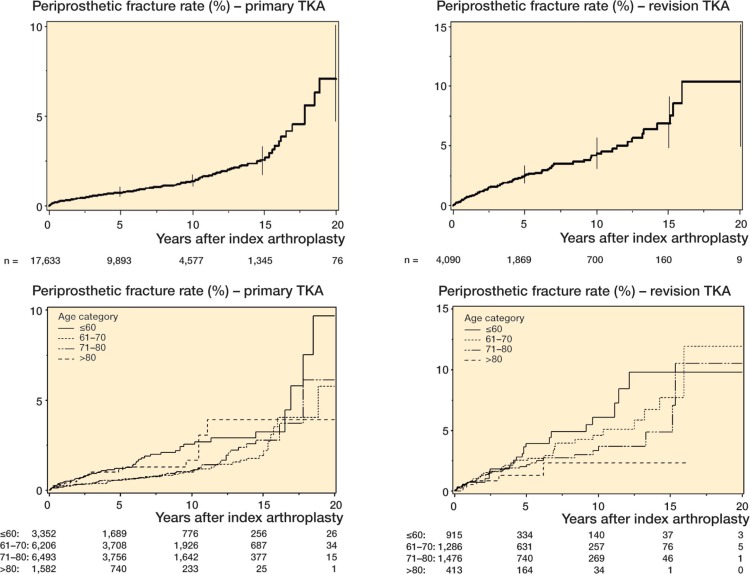

Survival free of periprosthetic fractures after primary and revision TKR

Using Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, we assessed cumulative postoperative periprosthetic fracture rates separately for the primary and revision TKR cohorts (Figure 1). We also performed the fracture rate analysis by age group, which was a significant predictor of fracture-free survival in multivariable-adjusted Cox regression analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Periprosthetic fracture rate after primary and revision TKA (top panels with error bars represent 95% confidence intervals), stratified further by age group (bottom panels). The number of patients at risk at baseline, 5-, 10-, 15- and 20-years is shown at the bottom of each panel.

Discussion

An important finding in the present study was that younger age ≤ 60 years) was associated with higher risk of postoperative periprosthetic fractures following primary TKR. Specifically, patients who were 61–70 years old had a 50% lower risk of periprosthetic fracture and those who were 71–80 years old had a 45% lower risk compared to patients who were aged 60 years or less. Age > 80 years was associated with a similar risk of periprosthetic fracture as age 60 years or younger. This suggested that there was a U-shaped relationship between age and periprosthetic fracture risk. It is reassuring that older patients, who receive the majority of TKRs, have lower—not higher—risk of periprosthetic fracture after TKR. Several possible factors may have contributed to this increased risk. A more active lifestyle in patients and involvement in sports in patients aged less than 60 years may put them at higher risk of trauma than those who are older. Younger patients who undergo primary TKR have associated with higher corticosteroid use and may lead to steroid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporosis (Beals and Tower 1996, Merkel and Johnson 1986), inflammatory arthritis (Merkel and Johnson 1986, Lindahl et al. 2006 a, b), and corticosteroid use (Porsch et al. 1996) are associated with higher risk of periprosthetic fracture. Since TKR is being increasingly performed in patients aged less than 65 years, the increased risk of periprosthetic fracture in younger patients is concerning. Previous research has not examined age as a predictor of periprosthetic fractures following primary TKR, except for one recent study from the Scottish registry (Meek et al. 2011), which reported that an age of > 70 years was associated with higher risk. The exact reason for this discrepancy in findings is unclear, but it may be related to differences in country setting (USA vs. Scotland), to patient characteristics, and to the variables that were adjusted in multivariable analyses in the 2 studies (several in our study but only age, sex, and revision surgery in the Scottish study). Our findings should be replicated/confirmed in future studies.

In patients with revision TKR, diagnoses of non-union, infection and of previous surgery with components removed were significant predictors of postoperative periprosthetic fracture. Compared to patients with loosening/wear/osteolysis, those with previous non-union were almost 5 times more likely to suffer from a postoperative periprosthetic fracture. This is not surprising, since abnormal mechanical stresses associated with non-union may predispose to subsequent periprosthetic fractures. A diagnosis of previous surgery with components removed was associated with twice the risk of periprosthetic fracture compared to loosening, wear, or osteolysis. These patients are some of the most challenging surgical cases due to previous surgical complications, and they may inherently be at higher risk of having postoperative complications in general.

An interesting observation in the present study was the borderline association between comorbidity and periprosthetic fracture risk in primary and revision TKR in multivariable-adjusted model 2 (overall: p = 0.05 and p = 0.08, respectively). A score of 3+ for comorbidities was statistically significant in both primary TKR (HR = 1.7, CI: 1.2–2.4) and revision TKR (HR = 1.9, CI: 1.1–3.1). Additionally, in both primary and revision TKR, a dose effect was seen in hazard ratio with an increasing comorbidity score of 1, 2, and 3+ (HR = 1.2, 1.4, and 1.7 for primary TKR and 1.1, 1.5, and 1.9 for revision TKR). We believe that this association in our study was real and borderline association significance is most likely due to the small number of periprosthetic fractures (< 200), despite the fact that the study covered a 20-year period.

Our estimates of cumulative incidence of periprosthetic fracture of 1.1% for primary TKR and 2.5% for revision TKR were in the range 0.3–2.5% previously reported for TKR (Aaron and Scott 1987, Merkel and Johnson 1986), as reviewed by Rorabeck and Taylor (1999) and McGraw and Kumar (2010). The previous studies differed regarding duration of follow-up (Merkel and Johnson 1986, Aaron and Scott 1987), which might explain the wide range. Despite the large sample size and long duration of follow-up, we had few patients at 20 years, i.e. 76 primary TKAs and 9 revision TKAs. As can be seen, there was a sharp drop-off in sample size after 15 years of follow-up. Thus, the estimates of fractures at 20 years after TKA should not be over-interpreted, and should be considered to be preliminary.

The strengths of the present study were the inclusion of a large number of fractures to allow robust analyses, inclusion of important modifiable variables (BMI and comorbidity), and the use of prospectively collected data.

The study had several limitations, and our findings should be interpreted with some caution. This was a single-center study at an institution that provides surgical care for referrals from other institutions and also primary orthopedic care to the local population (similar to community-based practices). Despite the large sample size, the number of fractures was in the 100–200 range, which may have meant that the study was underpowered for examination of some associations. To put this in perspective, most previous studies have been limited to < 20 events, with the exception of the national registry studies (Lindahl et al. 2006a,b, Meek et al. 2011). We included several important variables in the present study, but it is possible that there was residual confounding, as in any cohort study. We lacked a measure of osteoporosis in our database, which is a risk factor for fractures in general and might be a risk factor for periprosthetic fracture. These estimates should be considered to be conservative, since despite systematic prospective follow-up of patients with TKR for prosthetic-joint related complications (including all fractures) by trained registry staff (including obtaining medical records and radiographs from other facilities), loss to follow-up and under-reporting of fractures at non-Mayo facilities is possible.

In conclusion, in this large study of primary and revision TKR, we determined the frequency of postoperative periprosthetic fracture following primary and revision TKR. Younger age was a significant risk factor for periprosthetic fracture after primary TKR. Previous non-union and surgery with components removed were significant risk factors for periprosthetic fracture after revision TKR. These are non-modifiable risk factors. Surgeons and patients can have more informed discussion during the informed consent process in light of these findings.

Acknowledgments

JAS: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. DGL: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and revision of manuscript. MJ: acquisition of subjects and/or data, and analysis of data.

We thank Youlonda Lochler for assistance in identifying the cohort for analysis and Scott Harmsen for help with statistical analysis. This published material is the result of work supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Translational Science Award 1 KL2 RR024151-01 (Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Research) and of the resources and use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, AL, USA.

The study sponsor had no role in design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- Aaron RK, Scott R. Supracondylar fracture of the femur after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1987;(219):136–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals RK, Tower SS. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur. An analysis of 93 fractures. Clin Orthop. 1996;(327):238–46. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199606000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DJ, Kessler M, Morrey BF. Maintaining a hip registry for 25 years. Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Orthop. 1997;(344):61–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethea JS, 3rd, DeAndrade JR, Fleming LL, Lindenbaum SD, Welch RB. Proximal femoral fractures following total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1982;(170):95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya T, Chang D, Meigs JB, Estok DM. 2nd, Malchau H. Mortality after periprosthetic fracture of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(12):2658–62. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987a;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Braham RL, Fields SD, Douglas RG., Jr Morbidity during hospitalization: can we predict it? J Chronic Dis. 1987b;40(7):705–12. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowninshield RD, Rosenberg AG, Sporer SM. Changing demographics of patients with total joint replacement. Clin Orthop. 2006;(443):266–72. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000188066.01833.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp RW, Schmidt RG, Hanks G, Mak A, Esterhai JL, Jr., Heppenstall RB. Supracondylar fracture of the femur following prosthetic knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1987;(222):212–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delport PH, Van Audekercke R, Martens M, Mulier JC. Conservative treatment of ipsilateral supracondylar femoral fracture after total knee arthroplasty. J Trauma. 1984;24(9):846–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961;178:261–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE, 3rd, Sobel M. The results of treatment of supracondylar fracture above total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5(3):267–76. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(08)80082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatod M, Inacio M, Paxton EW, Bini SA, Namba RS, Burchette RJ, et al. Knee replacement: epidemiology, outcomes, and trends in Southern California: 17,080 replacements from 1995 through 2004. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(6):812–9. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Wei LJ, Amato D. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations; pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl H, Eisler T, Oden A, et al. Risk factors associated with the late periprosthetic femoral fracture. In: Lindahl H, editor. The periprosthetic femur fracture: a study from the Swedish National Hip Arthroplasty Register. Department of Orthopaedics, Sahlgenska Academy, Göteborg University; 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl H, Malchau H, Oden A, Garellick G. Risk factors for failure after treatment of a periprosthetic fracture of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006b;88(1):26–30. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.17029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw P, Kumar A. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(3):135–41. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0099-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek RM, Norwood T, Smith R, Brenkel IJ, Howie CR. The risk of peri-prosthetic fracture after primary and revision total hip and knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(1):96–101. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer D, Guralnik JM, Brock D. Prevalence and distribution of hip and knee joint replacements and hip implants in older Americans by the end of life. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(1):60–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03324481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel KD, Johnson EW., Jr Supracondylar fracture of the femur after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1986;68(1):29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsch M, Galm R, Hovy L, Starker M, Kerschbaumer F. Total femur replacement following multiple periprosthetic fractures between ipsilateral hip and knee replacement in chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Case report of 2 patients. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1996;134(1):16–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1037412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorabeck CH, Taylor JW. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur complicating total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30(2):265–77. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Lewallen D. Age, gender, obesity, and depression are associated with patient-related pain and function outcome after revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(12):1419–30. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1267-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Gabriel S, Lewallen D. The impact of gender, age, and preoperative pain severity on pain after TKA. Clin Orthop. 2008;11(466):2717–23. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0399-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Gabriel SE, Lewallen DG. Higher body mass index is not associated with worse pain outcomes after primary or revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(3):366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver F, Hynes D, Hopkinson W, Wixson R, Khuri S, Daley J, et al. Preoperative risks and outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty in the Veterans Health Administration. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(6):693–708. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Obesity; preventing and managing the global epidemic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]