Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To present new data on sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among US adolescents aged 10 to 19, and to compare the youngest adolescents’ behaviors with those of older adolescents.

METHODS:

Using nationally representative data from several rounds of the National Survey of Family Growth, we performed event history (ie, survival) analyses to examine timing of sexual initiation and contraceptive use. We calculated adolescent pregnancy rates by single year of age using data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the Guttmacher Institute, and the US Census Bureau.

RESULTS:

Sexual activity is and has long been rare among those 12 and younger; most is nonconsensual. By contrast, most older teens (aged 17–19) are sexually active. Approximately 30% of those aged 15 to 16 have had sex. Pregnancy rates among the youngest teens are exceedingly low, for example, ∼1 per 10 000 girls aged 12. Contraceptive uptake among girls as young as 15 is similar to that of their older counterparts, whereas girls who start having sex at 14 or younger are less likely to have used a method at first sex and take longer to begin using contraception.

CONCLUSIONS:

Sexual activity and pregnancy are rare among the youngest adolescents, whose behavior represents a different public health concern than the broader issue of pregnancies to older teens. Health professionals can improve outcomes for teenagers by recognizing the higher likelihood of nonconsensual sex among younger teens and by teaching and making contraceptive methods available to teen patients before they become sexually active.

Keywords: adolescents, contraceptive use, sexual activity, teen pregnancy

What’s Known on This Subject:

Among adolescents younger than 15, 18% have had sex and 16 000 pregnancies occur annually; among those aged 15 to 17, 30% have had sex and 252 000 get pregnant. Information on the youngest adolescents has not been previously published.

What This Study Adds:

Sexual activity and pregnancy are rare among 10-, 11-, and 12-year-olds, and sex is more likely to be nonconsensual. This arguably represents a different public health issue than sex among older teens, who have a greater need for contraception.

The sexual and reproductive behavior of adolescents has long been a focus of public discourse in the United States. Public health professionals have generally focused on the negative sequelae of teen pregnancies and births, and developed strategies to reduce teen sex and increase contraceptive use. Others have taken a more holistic approach toward sexuality and sexual behavior, arguing that Americans’ stigmatization of all adolescent sexuality contributes to our relatively high teen pregnancy rate.1

Despite substantial declines in adolescent pregnancy over the past 2 decades, teen sex remains a prominent bogeyman, as there is a broad public perception that a substantial proportion of young adolescents are sexually active. In 1998, the most recent survey to pose the question revealed that two-fifths of Americans thought that most young people have sex by age 14, and a quarter thought most have sex by age 13.2 Many also believe adolescents should not have access to contraception. In a 2007 poll, 46% of Americans said providing teens with birth control would encourage sexual behavior, 54% believed teens should not be allowed access to contraception until ages 16 to 19, and 6% believed young people should not be allowed to obtain birth control at all.3

Recent public policy debates on access to contraception have drawn attention to the behaviors of young adolescents. For example, in overturning the US Food and Drug Administration’s 2011 recommendation to make the emergency contraceptive pill Plan B available over the counter to people of all ages, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius and President Barack Obama cited concerns about the fertility of 10- and 11-year-olds and the propriety of these young adolescents having access to the method,4 despite evidence that Plan B is safe for women of all ages5 and that teenage women can follow the instructions for emergency contraception at a level equal to adult women.6,7 These comments imply that their speakers believe there is a substantial level of sexual activity among 10- and 11-year-old girls.

Past work has examined the sexual and reproductive behavior of adolescents 14 and younger,8 but those publications are based on data from the late 1990s, and none of them presented information on the youngest adolescents (those 12 and younger). In this article, we make use of newly available public data sets and have sought additional data to make updated and more precise estimates of sexual activity, contraceptive use, and pregnancy rates among the youngest adolescents as well as older teens.

Methods

Sexual Activity

We used age at first heterosexual vaginal intercourse as our measure of sexual activity. To look at the timing of sexual initiation, we used data from several waves of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a nationally representative survey of women and men aged 15–44, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, that is arguably the best source of information on sexual activity, partnership patterns, contraceptive use, and childbearing in the United States. We initially used data from the 1984–1993 birth cohorts, comprising 3242 females and 3104 males. The NSFG asks its respondents to indicate the month and year in which they first had sex, as well as birth month and year. We performed event history analyses (specifically, Kaplan-Meier life-table analyses), which allow one to incorporate the experience of all respondents, including those who reached the interview without having had sex. We used these methods to determine the proportion of individuals who had had sex by each exact age (ie, by a particular birthday) for both females and males.

We also examined a related measure, the proportion of individuals of each (current) age who had had sex. For example, the group “14-year-olds” includes individuals ranging from 14 years and 0 months old to 14 years and 11 months old, so to determine the number of 14-year-olds who had ever had sex, we calculated the proportion of people who had had sex by age 14 years and 0 months, the proportion who had had sex by age 14 years and 1 month, and so on through 14 years and 11 months, and averaged these 12 proportions.

Based on evidence that the young adolescent age group (aged 14 and younger) is at greatest risk of experiencing sexually violent crimes,9 we also examined the relationship between timing of sexual debut and whether the first sexual experience was voluntary among a recent cohort of women. Because the male data set did not include the necessary variable, this part of the analysis was restricted to females. We calculated the proportion who reported that their first sex was nonconsensual (among those who had had sex by each exact age), using data from the 1984–1993 birth cohorts in the 2006–2010 wave of the NSFG. We used 1-year age categories up to age 12, and larger age groups up to age 20 to reduce random variation.

To look at trends over time in age at first sex, we used the 1988, 1995, 2002, and 2006–2010 rounds of the NSFG. We separated the female NSFG respondents into birth cohorts from 1939 to 1991 and calculated the ages by which 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% of each cohort had had sex; these results were again based on Kaplan-Meier life tables.

Contraceptive Use

Most Americans initiate sex during their teen years,10 and among teens, the large majority of pregnancies are unintended.11,12 In addition, contraceptive use at first sex has been recognized as an indicator of later consistency of use.13 Because of this, we examined the interval of time between first sex and first contraceptive use. We included all contraceptive methods reported by respondents, including hormonal methods, barrier methods, withdrawal, and periodic abstinence. We calculated the proportion of individuals whose first contraceptive use occurred in the same month as (or before) their first sex; for those who did not use contraception at first sex, we looked at how long it took them to initiate contraceptive use. Because our primary interest in this work was the impact of age at first sex on time to contraceptive initiation, we performed this analysis separately by single year of age at first sex.

Pregnancy and Pregnancy Outcomes

Finally, we calculated pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates by single year of age at pregnancy outcome for 2008. Pregnancies include births, abortions, and fetal losses. To make these calculations, we combined data on births from the National Center for Health Statistics and data on abortions from a national census of abortion providers and a nationally representative survey of abortion patients conducted by the Guttmacher Institute. In each case, we used data by single year of age whenever possible. Single-year-of-age breakdowns were not available for abortions to girls aged 12 and younger, so we distributed them in the same ratio as births. Fetal losses were estimated as 20% of births plus 10% of abortions, a convention used when empirical data are not available.14 To calculate rates for each age group, we summed births, abortions, and fetal losses, and then divided by age-specific populations. Denominators for rates were based on population estimates produced by the Census Bureau in collaboration with the National Center for Health Statistics for July 1, 2008.15 Additional details on this methodology are available elsewhere.12 Additionally, we calculated the pregnancy rate for sexually active teens by using the same number of pregnancies in the numerator, but using a population denominator that included only teens of that age who had ever had sex, based on reports in the NSFG.

Results

Sexual Initiation

Reports from women aged 15 to 24 at interview in the 2006–2010 NSFG indicate that few young adolescents have had sex (Table 1). The proportion of females who have had sex by the time they reach their 12th birthday is <1%. Measured another way, <1% of 11-year-old girls and ∼1% of 12-year-old girls have had sex. Similarly, only 2% and 5% of females have had sex by their 13th and 14th birthdays, respectively. By the middle teens, however, these proportions have increased, but teens who are sexually active remain in the minority: 19% of 15-year-old females and 32% of 16-year-old females have had sex. Some 26% of all women have not had sex by their 20th birthday.

TABLE 1.

Sexual Initiation by Single Year of Age, Women and Men Born 1984–1993

| Age (x) | Percent Who Had Sex by Their xth Birthday | Percent of x-year-olds Who Have Had Sex | Of Females Who Had Sex by Their xth Birthday, % for Whom First Sex Was Nonconsensual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, % | Female, % | Male, % | All, % | Female, % | Male, % | ||

| 10 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 62 |

| 11 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 50 |

| 12 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 23 |

| 13 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 3.4 | 7.3 | 7.2 |

| 14 | 7.9 | 5.4 | 10 | 11 | 8.6 | 13 | |

| 15 | 16 | 14 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 22 | 6.8 |

| 16 | 27 | 26 | 29 | 33 | 32 | 35 | |

| 17 | 41 | 40 | 43 | 48 | 47 | 49 | 4.8 |

| 18 | 56 | 54 | 57 | 61 | 60 | 61 | |

| 19 | 67 | 66 | 67 | 71 | 70 | 71 | |

| 20 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 76 | 77 | 76 | |

Figures for young males are also low, although slightly higher than for females. Approximately 2% of males have had sex by their 12th birthday, and 5% and 10% have done so by their 13th and 14th birthdays. Among teens aged 15 and older, figures for males at each age are only a few percentage points higher than females: 22% of 15-year-old males and 35% of 16-year-old males have had sex, whereas the proportion of men who have not had sex by their 20th birthday is the same as it is for women.

Table 1 also displays the percent of females who reported that their first sex was nonconsensual among those who had had sex by each birthday. These figures establish that sex among the youngest adolescents is much more likely to be coerced than among older age groups. Sixty-two percent of female respondents who had sex by their 10th birthday reported that their first experience was nonconsensual, compared with 50% of those whose first sex occurred by age 11 and 23% by age 12. This proportion decreases substantially with increasing age at sexual debut: Among those who had sex by age 13 or 14, only 7% reported that their first sex was not consensual, and among those who had sex by age 17 or older, fewer than 5% reported this.

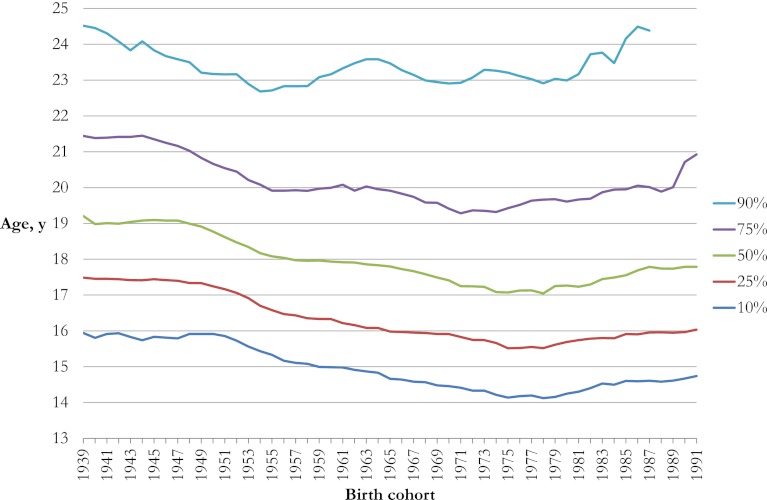

Figure 1 reveals historical trends in the ages by which 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% of females had had sex. The 10% line never falls as low as age 14. In other words, at no time in the past 50 years was it the case that ≥10% of girls had had sex by their 14th birthday. Figures for older teens are also worth noting: The median age at first sex never fell below 17, and at least a quarter of young adults in all birth cohorts had not had sex by 19. Furthermore, this figure reveals that members of the most recent cohorts are less likely to have had sex (by every age) than those born in the 1970s, indicating that more young people are delaying sexual initiation than in the recent past.

FIGURE 1.

Ages by which 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% of individuals have had sex, by birth cohort.

Contraceptive Use

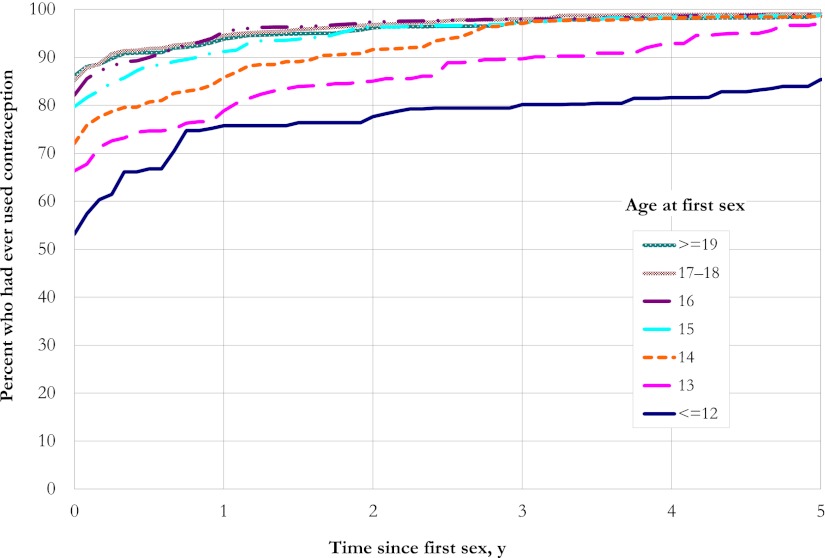

Figure 2 indicates the time from women’s first sex to first contraceptive use. The curves do not start at 0%, indicating that substantial proportions of women use contraception in the same month that they first had sex. Thus, for example, 82% of 16-year-olds use contraception at first sex; by 1 year after first sex, 95% of those who had sex for the first time at age 16 have used contraception.

FIGURE 2.

Time from first sex to first contraceptive use, by age at first sex, women aged 15 to 29 at interview, NSFG 2006–2010.

One salient finding from Fig 2 is that teens who initiate sex at young ages take longer to initiate contraceptive use. Only 52% of those starting sex at 12 or younger use contraception during the month of first sex, and figures are relatively low for 13- and 14-year-olds as well.

Among those who initiate sex at age 15, however, contraceptive use patterns are similar to those of women who start having sex at an older age. Eighty percent of 15-year-old sexual initiators use contraception in the same month, compared with 85% of 17- to 18-year-olds. A Cox proportional-hazards regression model comparing age groups (not shown) indicated that the pattern of contraceptive initiation by those initiating sex at 14 and younger was significantly different from those 19 and older, but 15-year-olds and older did not differ significantly from 19-year-olds.

Pregnancies and Pregnancy Outcomes

Table 2 reveals that the pregnancy rate among girls 12 and younger is minuscule (and, in fact, the absolute number of pregnancies is also remarkably small). Pregnancies among those 11 and younger are exceedingly rare, and only 1 in ∼7000 12-year-olds experiences a pregnancy in a given year. Among girls 13 and younger, the majority of pregnancies (excluding miscarriages) end in abortion, whereas for girls 14 and older, more pregnancies end in birth than abortion; for girls 17 and older, twice as many pregnancies end in birth as abortion. Pregnancy rates among ever-sexually-active girls age 13 and younger are also low, likely due to infrequent sexual activity among the youngest sexually experienced teens.8,16

TABLE 2.

Pregnancy, Birth, and Abortion Rates by Single Year of Age, 2008

| Age at Pregnancy Outcome | Number of Pregnancies | Pregnancy Ratea | Birth Ratea | Abortion Ratea | Births/ Abortions | Pregnancy Ratea Among Sexually Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <=11b | 90 | .04 | .02 | .02 | .69 | 7 |

| 12 | 290 | .14 | .05 | .07 | .69 | 12 |

| 13 | 2300 | 1.1 | .4 | .5 | .79 | 33 |

| 14 | 10 200 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.16 | 58 |

| 15 | 33 900 | 16 | 8.1 | 5.8 | 1.40 | 86 |

| 16 | 76 500 | 36 | 19 | 11 | 1.71 | 110 |

| 17 | 134 500 | 62 | 36 | 18 | 2.01 | 133 |

| 18 | 211 500 | 95 | 56 | 25 | 2.24 | 157 |

| 19 | 294 100 | 136 | 81 | 36 | 2.25 | 194 |

| 20 | 327 600 | 156 | 93 | 40 | 2.30 | 204 |

Rates are per 1000 females in the particular age group.

Denominator for rates is females aged 11.

Discussion

Our study is subject to some limitations. Dates of first sex and first contraceptive use are retrospectively reported by respondents. However, these are highly salient events, implying that recollection of these dates should be largely accurate. While misreporting of sexual behavior is a concern in all self-reported surveys, we believe underreporting of sexual initiation, the measure studied here, to be less of a concern than underreporting of current sexual behavior. In addition to the issue of salience discussed above, individuals who had first sex at young ages would be more likely to report this information after some time has passed than immediately afterward, and almost all NSFG reporting about first sex occurs many years after the event. In addition, underreporting frequently manifests as missing data, ie, refusal to answer a question; in the 2006 NSFG, >1% of eligible female respondents had a missing value for age at first sex.17 In comparison, 3.5% of eligible respondents had a missing value for number of lifetime partners, which supports our belief that reports about current sexual behavior are more susceptible to social desirability bias than information about events that preceded the interview by a number of years.

In addition, the method used in the survey to ask respondents if their first sexual intercourse was nonconsensual has been found to be susceptible to underreporting, so we strongly suspect that the proportion of young adolescents, in particular, whose first sexual experience was coerced is higher than our data were able to capture.18

Because in this article we define sexual activity to refer only to heterosexual vaginal intercourse, our results provide a limited portrait of adolescent sexual behavior. Although this narrow definition combined with data on contraceptive use provide a basis from which to draw conclusions about teens’ risks for unintended pregnancy and parenthood, the same cannot be said for other health outcomes related to sexual activity more broadly defined, such as sexually transmitted infections. Finally, our measures of sexual activity and contraceptive use are based on the first instance of each, and therefore do not reflect frequency of sexual activity, effectiveness of the contraceptive method, or consistency of contraceptive use over time. Nonetheless, we argue that these events serve as effective proxies for later behaviors.

Taken together, the findings in this article indicate that sexual activity has been rare among the youngest adolescents for decades, and pregnancy is even rarer. Concerns about substantial levels of sexual activity among young adolescents are unfounded, and the pregnancy rate (indeed, the absolute number of pregnancies) among these girls is vanishingly small. When it occurs, sexual activity among the youngest adolescents is frequently of a different nature than that of middle and older teens, in that it is frequently nonconsensual. Although individual pregnancies to girls this young are significant events, they arguably represent a different public health concern than the broader issue of pregnancies to older teens. Among young teens, lower rates of contraceptive use at first sex are probably due to their lower likelihood of having information about and access to contraceptive methods. Substantial proportions, although minorities, of 15- and 16-year-old girls have had sex. It is these latter teens who are most at risk for experiencing an unwanted teenage pregnancy, and who are therefore most affected by restrictions, legal or practical, to using contraception.

Conclusions

Pediatricians and other child and adolescent health professionals are well placed to screen for unwanted sexual activity among patients of all ages, with the awareness that sexual activity among the youngest adolescents is especially likely to be nonconsensual. In addition, teaching young adolescents about contraceptive methods and prescribing or offering methods before they are likely to become sexually active is prudent: Knowledge of and access to contraception at an earlier age would help those adolescents who initiate sex early, and would likely increase contraceptive use among older teens as well. No study of sex education programs to date has found evidence that providing young people with sexual and reproductive health information and education results in increased sexual risk-taking.19 In addition, fears that early exposure to contraceptive methods would encourage sex among young adolescents should be assuaged by recent evidence that vaccination against human papillomavirus did not increase sexual activity among 11- and 12-year-old girls.20 Although the high rate of sexual coercion among young adolescents is certainly cause for concern, it should not be used as a brush with which to tar sexual activity among those older teens who are capable of both deciding to initiate sex and, based on our findings, able to initiate contraceptive use when doing so.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Heather Boonstra, Laura Lindberg and Mia Zolna for reviewing earlier drafts of this paper.

Glossary

- NSFG

National Survey of Family Growth

Footnotes

Dr Finer conceptualized and designed the analysis, conducted analyses, drafted the initial article and contributed to its revision, and approved the final article as submitted; and Dr Philbin conducted analyses, reviewed and revised the article, and approved the final article as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by grant 1 R01 HD059896 from the US National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Schalet A. Not Under My Roof: Parents, Teens, and the Culture of Sex. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. Sex in the 90s: 1998 National Survey of Americans on Sex and Sexual Health. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 1998. Available at: www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/Sex%20in%20the%2090s%20%20%201998%20National%20Survey%20of%20Americans%20on%20Sex%20and%20Sexual%20Health.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2012

- 3.The Associated Press. Teen contraception study. Washington, DC: The Associated Press; 2007. Available at: http://surveys.ap.org/data/Ipsos/national/2007-10-26%20AP%20Teen%20Contraception%20Study%20topline.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2012

- 4.Sebelius K. A statement by US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. 2011. Available at: www.hhs.gov/news/press/2011pres/12/20111207a.html. Accessed October 24, 2012

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cremer M, Holland E, Adams B, et al. Adolescent comprehension of emergency contraception in New York City. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):840–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raymond EG, L’Engle KL, Tolley EE, Ricciotti N, Arnold MV, Park S. Comprehension of a prototype emergency contraception package label by female adolescents. Contraception. 2009;79(3):199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert B, Brown S, Flanigan C, eds. 14 and Younger: The Sexual Behavior of Young Adolescents (Summary). Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truman JL. Criminal victimization, 2010. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 235508. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011. Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv10.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2013

- 10.Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Dawson BS. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, 2002. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23(24). Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38(2):90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shafii T, Stovel K, Davis R, Holmes K. Is condom use habit forming? Condom use at sexual debut and subsequent condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(6):366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leridon H. Human Fertility: The Basic Components. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intercensal estimates of the July 1, 2000–July 1, 2009, United States resident population by single year of age, sex, bridged race, and Hispanic origin. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics and New York, NY: US Census Bureau; 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/NCHS/nvss/bridged_race.htm. Accessed February 19, 2013

- 16.Martinez G, Copen CE, Abma J. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23(31). Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011 [PubMed]

- 17.Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(5):859–883 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Fisher B, Cullen F, Turner M, National Institute of Justice. The sexual victimization of college women. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2000. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/182369.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2012

- 19.Boonstra H. Advancing sexual education in developing countries: evidence and implications. Guttmacher Pol Rev. 2011;14(3):17–23 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bednarczyk RA, Davis R, Ault K, Orenstein W, Omer SB. Sexual activity-related outcomes after human papillomavirus vaccination of 11- to 12-year-olds. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):798–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]