Abstract

Background

High-resolution optical imaging provides real-time visualization of mucosa in the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) which allows non-invasive discrimination of benign and neoplastic epithelium. The high-resolution microendoscope (HRME) utilizes a fiberoptic probe in conjunction with a tissue contrast agent to display nuclei and cellular architecture. This technology has broad potential applications to intraoperative margin detection and early cancer detection.

Methods

Our group has created an extensive image collection of both neoplastic and normal epithelium of the UADT. Here, we present and describe imaging characteristics of benign, dysplastic, and malignant mucosa in the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, and esophagus.

Results

There are differences in the nuclear organization and overall tissue architecture of benign and malignant mucosa which correlate with histopathologic diagnosis. Different anatomic subsites also display unique imaging characteristics.

Conclusion

HRME allows discrimination between benign and neoplastic mucosa, and familiarity with the characteristics of each subsite facilitates correct diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Failure to obtain clear (tumor free) surgical margins is an adverse prognostic factor for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [1, 2]. Thus, during ablative cancer surgery complete removal of all malignant tissue is necessary to maximize survival and decrease the chance of recurrence. However, unnecessary removal of normal tissue can lead to serious deficiencies in the ability to speak, swallow, or chew, with an overall decreased quality of life [3, 4]. To obtain clearmargins, the surgeonmust discriminate between neoplastic and surrounding normal tissue during tumor resection; currently, the extent of disease is defined using visual examination and palpation. Intraoperative “frozen section” pathological margins are often necessary to confirm critical or questionable tumor margins. Although frozen sections during ablative head and neck cancer surgery are a vital adjunct to visual and tactile examination, the procedure is costly and time-consuming, and discrepancies between frozen section margins and final pathology are common [5–7]. Thus, techniques for real-time visualization of tumor margins at the time of surgery have the potential to reduce the number and enhance the accuracy of frozen section determinations.

Image guided cancer surgery is an emerging area of research, and several optical imaging modalities have been proposed to improve intraoperative delineation of tumor margins [8]. These include wide-field imaging of tissue autofluorescence to delineate tumor margins based on loss of autofluorescence and high-resolution optical imaging to image margins based on changes in tissue architecture and cellular morphology [9–14]. Imaging of tissue autofluorescence during surgical resection has been suggested to decrease recurrence rate of oral cancers and currently a randomized, multicentre, double blind, and controlled surgical trial is underway to further validate these preliminary results [15, 16].

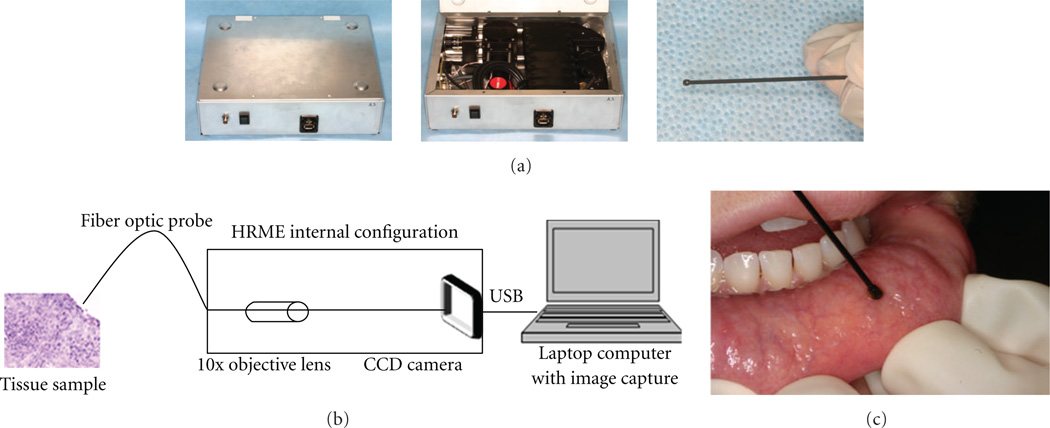

High-resolution images, such as those provided by confocal microscopy provide the ability to spatially resolve morphological changes in the epithelia that occur during neoplasia, including changes in nuclear morphology and distribution [17, 18]. High-resolution confocal optical images can reveal morphologic details with similar quality to that which can be seen in histological slides, but are obtained in a non-invasive manner and without the need for slide preparation and staining. However, despite their utility and impressive resolution, confocal imaging devices are complex and expensive. As an alternative approach, we have previously described a portable high-resolution microendoscope (HRME), which utilizes a flexible fiberoptic probe to interrogate tissue treated with a topically applied fluorescent nuclear contrast agent. This system allows visualization of epithelial architecture at video rate. This device (Figure 1) has been used to identify Barrett’s dysplasia in the esophagus, axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer, and neoplasia in resected oral squamous carcinoma specimens with high sensitivity and specificity [19–21]. In a recent study, medical professionals were readily able to discriminate benign and malignant images of the UADT following a brief training presentation, suggesting the potential utility of this approach for image-guided surgery in the head and neck [22].

Figure 1.

The high resolution microendoscope (HRME). (a) External and internal appearance of the imaging device. (b) Simplified schematic diagram of the HRME. (c) In vivo use of the HRME on healthy mucosa of the lip.

In this paper, we describe the imaging characteristics of benign mucosa and squamous cell carcinoma of the UADT, and present representative HRME images from ex vivo surgical specimens and in vivo endoscopy as an atlas for image-guided surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and Specimen Accrual

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both Mount Sinai School of Medicine (GCO 09-2045) and Rice University (09-166E). Patients over the age of 18 with biopsyproven head and neck squamous cell carcinoma scheduled for ablative surgery were approached for participation. All patients participated in the informed consent process.

2.2. Imaging System

The HRME has been previously described in detail [23]. This system consists of a fiberoptic probe which is placed in contact with the mucosal surface, an LED light source, and a CCD camera which is connected to a laptop computer for image capture and storage. The platform is designed to be used with proflavine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), a fluorescent nuclear contrast agent which reversibly binds to DNA [24]. Proflavine has been used extensively in in vivo studies of the gastrointestinal tract in Europe and Australia without reported adverse events and is a main component of the triple dye used to prevent infection on the umbilical stump of newborns [25–27]. Proflavine is buffered with saline to 0.01% solution, and a small amount is applied topically by gently swabbing or spraying the epithelium.

2.3. Imaging of Specimens

For images of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx, areas of interest, including grossly normal tissue, tumor, and the clinical tumor/normal interface (margin) were stained with proflavine following standard-of-care surgical resection. Immediately after topical application of the dye, the fiberoptic probe was used to view these areas and capture either 3–10 still images or movie clips of 3 seconds duration. Movie clips were converted to still images using Windows Movie Maker (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). A 3-mm punch biopsy of the imaged site was analyzed by conventional H&E histopathology by a board-certified pathologist.

In vivo Images of the esophagus were obtained during endoscopy. The esophagus was sprayed with 1–3ml of 0.01% proflavine. The fiberoptic probe was then inserted through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. The probe was placed in gentle contact with themucosa and video images obtained in real time. A small dimple was made on the imaged site using the probe tip, and the imaged area was biopsied and analyzed by conventional H&E histopathology.

HRME images were analyzed to identify imaging features of benign and malignant mucosa which correlate with histopathological diagnosis, including nuclear size and shape, nuclear density, and overall tissue architecture.

3. Results

We generated an extensive library of images from various sites in the upper aerodigestive tract including the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, and esophagus. From June 2009 to May 2011, sixty four surgical specimens were imaged with the HRME. Over 1400 still images of benign, malignant, and dysplastic mucosa at various anatomical sites were obtained. Table 1 provides the breakdown by site of our current imaging collection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of imaging database.

| Anatomical site (# of surgical specimens) |

Number of sites with listed pathological diagnoses |

Number of images in collection |

|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity (25) | ||

| Normal | 35 | 195 |

| Dysplasia | 8 | 57 |

| Cancer | 41 | 394 |

| Total | 84 | 646 |

| Oropharynx (29) | ||

| Normal | 31 | 192 |

| Dysplasia | 9 | 51 |

| Cancer | 31 | 212 |

| Total | 71 | 455 |

| Larynx (10) | ||

| Normal | 21 | 112 |

| Dysplasia | 4 | 17 |

| Cancer | 19 | 226 |

| Total | 44 | 355 |

| All sites (64) | ||

| Normal | 87 | 499 |

| Dysplasia | 21 | 125 |

| Cancer | 91 | 832 |

| Total | 199 | 1,456 |

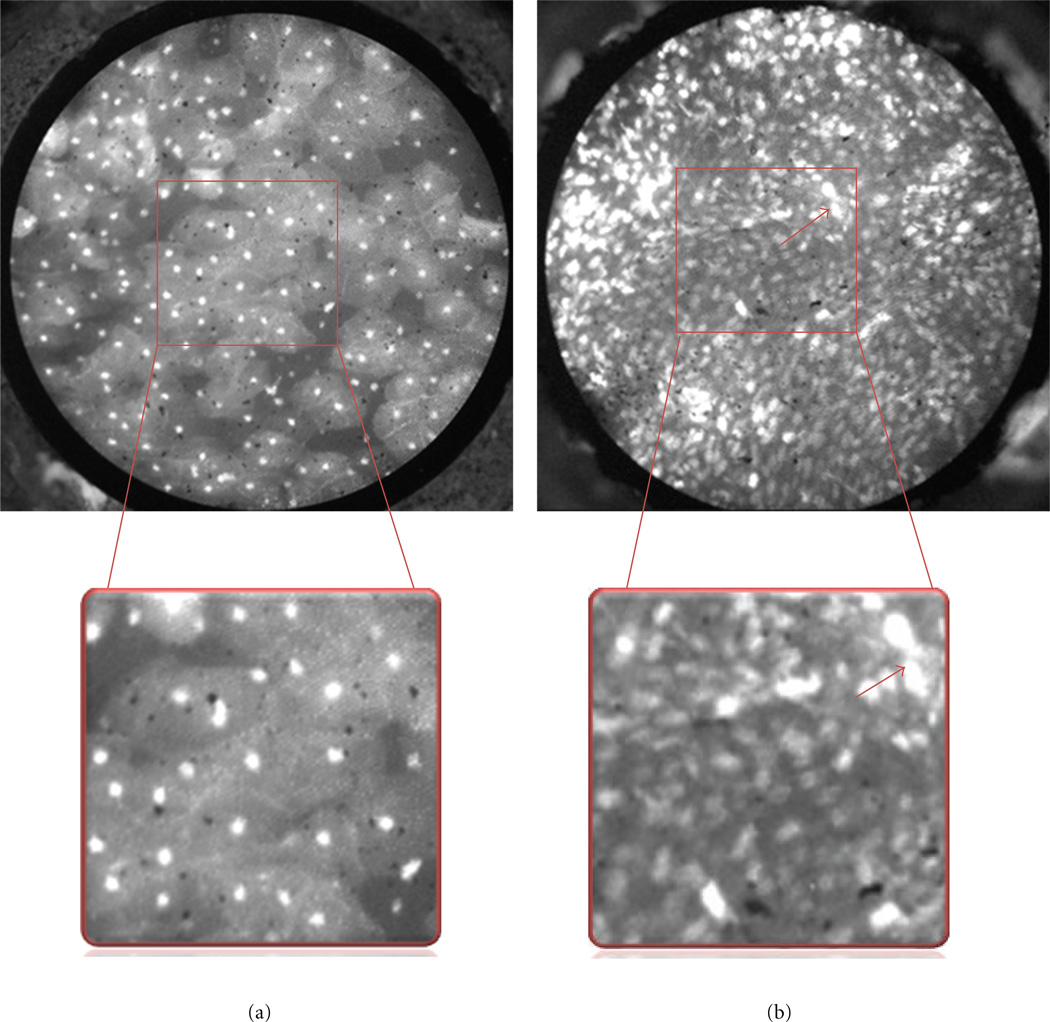

For each anatomic site in the UADT, reproducible differences were observed in HRME images of benign and malignant mucosa. In general, HRME images of benign mucosa are characterized by nuclei of consistent, regular size, which are evenly spaced. This contrasts with malignant mucosa, in which the nuclei are enlarged and display crowding with lack of organized tissue architecture, corresponding to increased cellularity found in cancerous tissue (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Features of benign and malignant squamous epithelium. Benign (left) and malignant (right) epithelium from the surface of the tonsil. The boxed area is magnified to display differences in nuclear size, density, and pleomorphism. Note that nuclei in benign tissue are small, punctuate dots that are similarly sized and evenly spaced, while malignant nuclei are larger (red arrow), pleomorphic and irregularly spaced with crowding and loss of normal architecture.

While differences in HRME images of benign and malignant tissue are generally consistent across anatomic sites, eachmucosal site has a slightly different imaging appearance; thus, it is important for those interpreting HRME images to have familiarity with each subsite of the UADT.

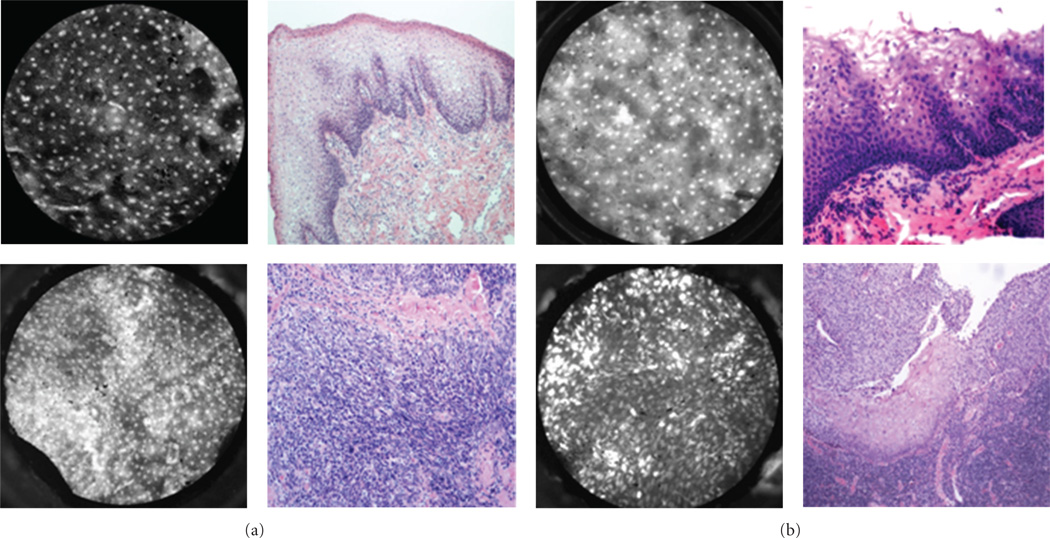

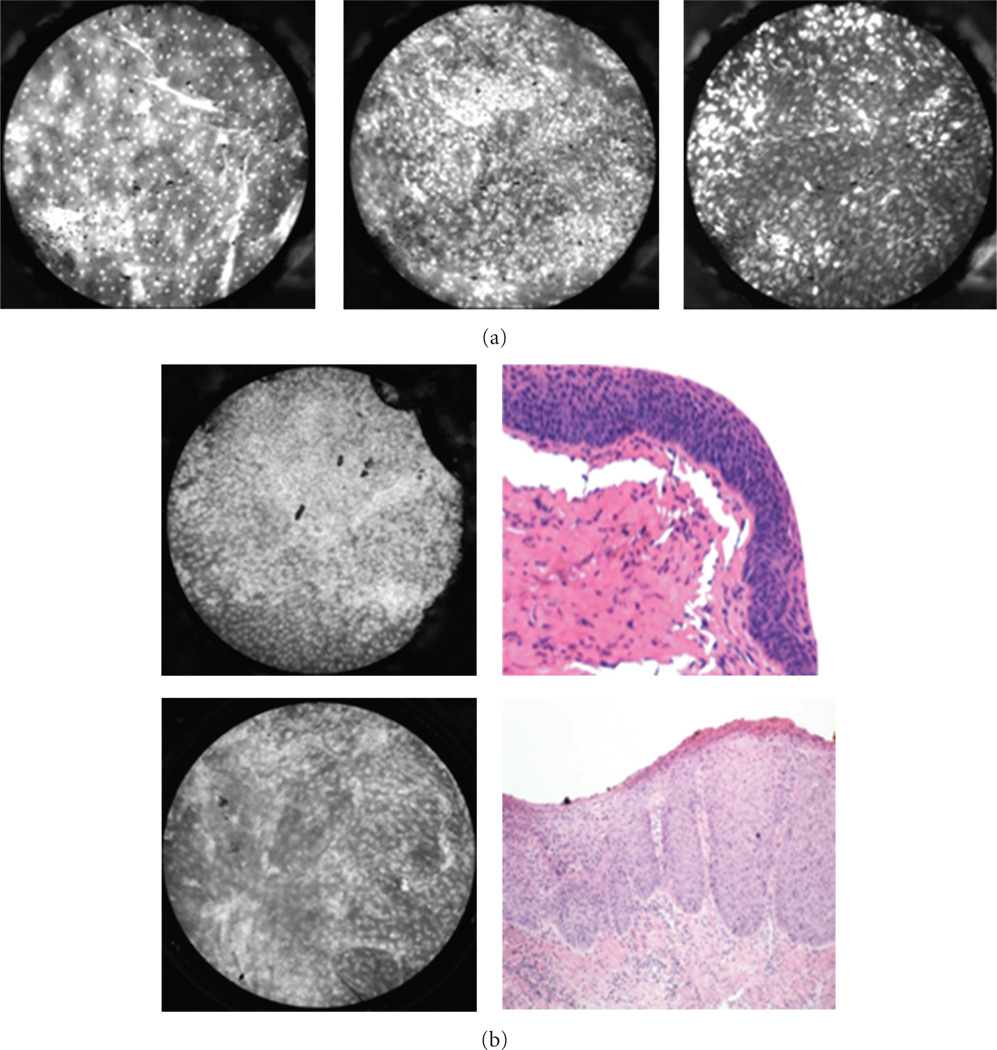

In the oral cavity (Figure 3), HRME images obtained from the floor of mouth, tongue, and lip consistently display the previously described features of benign and malignant mucosa. However, images of heavily keratinized sites, like the hard palate and gingiva (Figure 3(d)), can appear hyperfluorescent due to the affinity of proflavine for keratin.

Figure 3.

Oral cavity: representative images with corresponding histopathology (H&E original magnification 100x) of benign (top) and malignant (bottom) mucosa. (a) Floor of mouth. (b) Tongue. (c) Mucosal lip. (d) Maxilla and overlying gingiva. indicates keratinizing squamous epithelium which appears hyperfluorescent on HRME. Red arrow indicates cotton fiber (artifact) present on the tissue following application of proflavine.

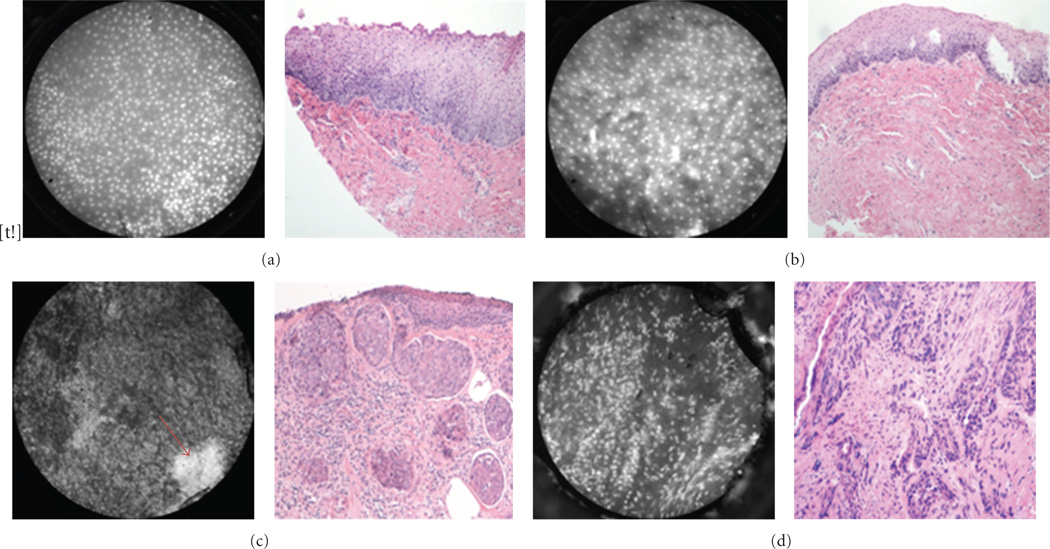

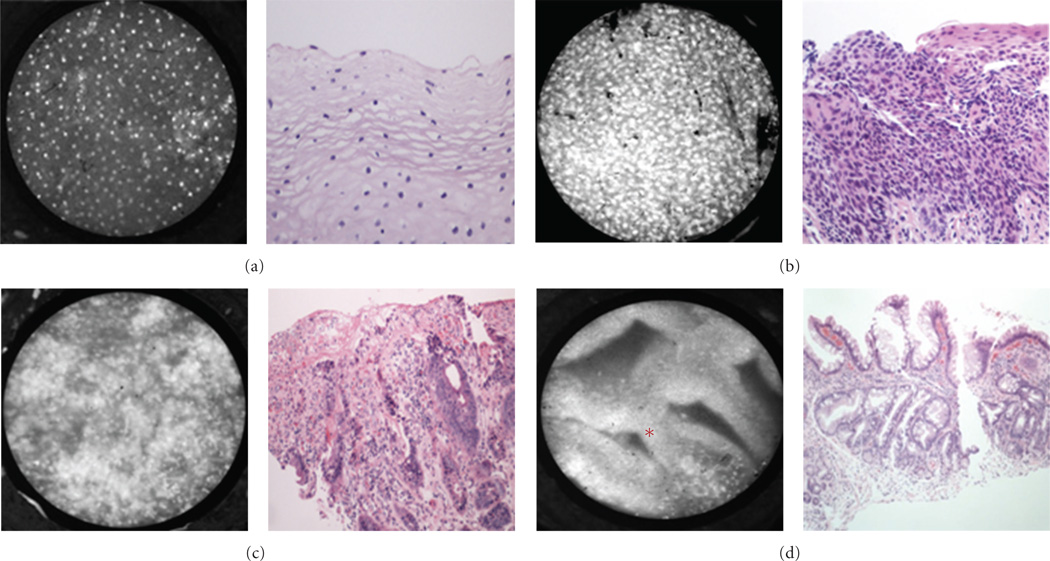

Images of the oropharynx (base of tongue and tonsil), reliably display features of benign and malignant mucosa (Figure 4). Again, the nuclei of benign mucosa are punctate and regularly spaced, whereas images from malignant mucosa show nuclei which are irregular, enlarged, and extremely disorganized. Characteristics of benign and malignant tissue from the larynx (Figure 5) are consistent with those obtained from other sites. However, pseudostratified ciliated columnar (respiratory) epithelium is a prominent feature of this region and inexperienced observers may confuse the increased number of nuclei in respiratory epithelium with dysplastic or cancerous mucosa.

Figure 4.

Oropharynx: representative images with corresponding histopathology (H&E original magnification 100x) of benign (top) and malignant (bottom) mucosa. (a) Base of tongue. (b) Tonsil.

Figure 5.

Larynx: representative images with corresponding histopathology (H&E original magnification 100x) of benign (a and b) and malignant (c and d) mucosa. (a), (b), and (c) are from the supraglottic larynx. (d) is from a glottic tumor. Arrow indicates hyperflourescent area from proflavine staining.

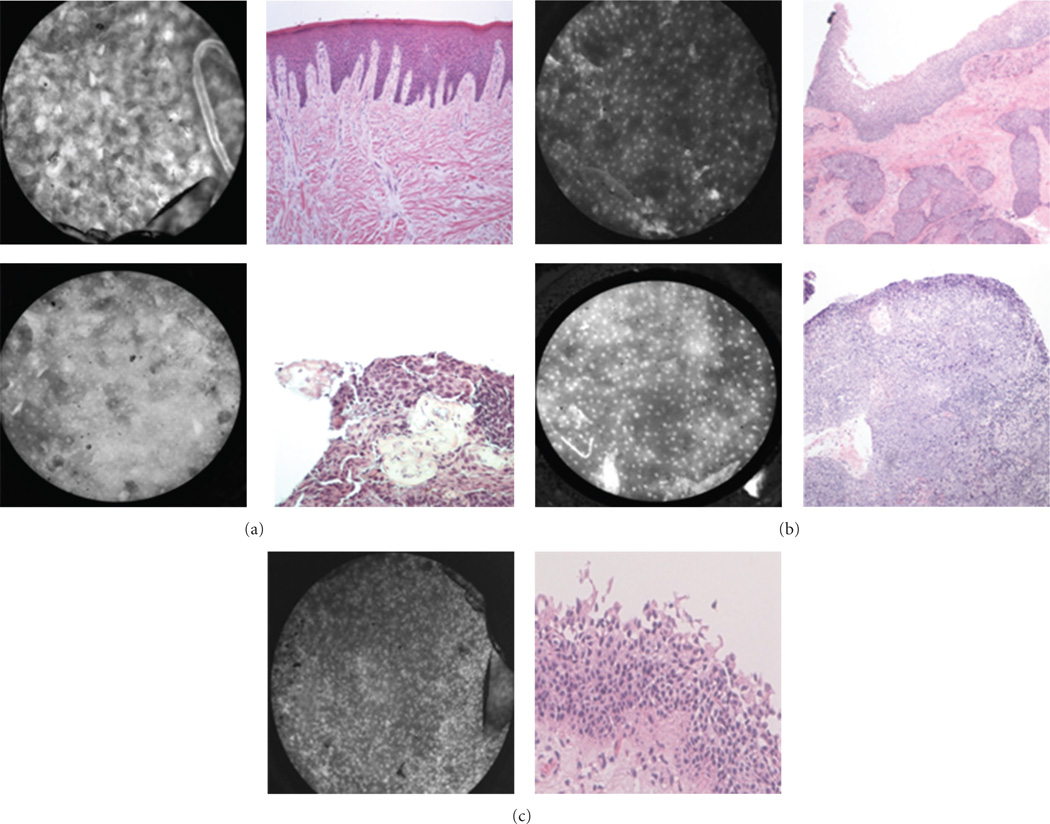

Dysplasia is a common feature of UADT mucosa exposed to environmental carcinogens such as tobacco and alcohol, and dysplastic tissue has unique imaging features (Figure 6). Like malignant tissue, dysplastic mucosa also contains increased density of cell nuclei. However, dysplastic mucosa differs from malignant mucosa in that the tissue architecture is disorganized to varying degrees rather than absent. While it can be difficult to distinguish between cancerous and dysplastic mucosa, the HRME characteristics of both pathologies are quite distinct from those of normal tissue. Thus, when choosing a biopsy site or determining surgical margins, abnormal mucosa is readily identified.

Figure 6.

Characteristics of dysplasia. (a) Benign mucosa (left), high-grade dysplasia (center), and squamous cell carcinoma (right) on the surface of the tonsil. (b) Dysplasia of the larynx (top) and floor of mouth (bottom) with corresponding histopathology (H&E original magnification 100x). Note enlarged and crowded nuclei with loss of normal cellular architecture.

The fiberoptic probe can easily be delivered through a flexible endoscope and used during diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopy of the esophagus (Figure 7). The appearance of benign squamous epithelium in the esophagus is almost identical to those of benign squamous epithelium at other sites of the UADT, displaying evenly spaced nuclei and intact cellular architecture (Figure 7(a)). Images of tissue with dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma (Figures 7(b) and 7(c)) feature both increased number of nuclei and increased nuclear size. Interestingly, in the lower esophagus, the appearance of glandular mucosa is quite distinct from squamous mucosa, thus making it possible to identify the precancerous condition Barrett’s metaplasia (Figure 7(d)).

Figure 7.

Esophagus. Representative images of (a) benign squamous epithelium; (b) high grade dysplasia; (c) adenocarcinoma; (d) Barrett’s metaplasia (H&E originalmagnification 100x). Notice glandular structures have imaging characteristics distinct fromsquamous epithelium, indicated by *.

4. Current Limitations

Keratinized tissue (Figure 8) is a diagnostic challenge, since proflavine has an affinity for keratin which can obscure the visualization of nuclei. The epithelium of both benign and cancerous tissue can contain keratin, which is a normal constituent of the epithelium on the alveolar ridge and hard palate. However, ectopic keratinization can accompany neoplastic transformation, and keratinization of normally nonkeratinized tissue is thus a potential diagnostic hallmark of cancer. Submucosal tumor spread is another significant challenge, since the depth of penetration of the fiberoptic probe is limited to approximately 25–50 micrometers (Figure 8(b)). Therefore, images may be classified as normal when benign epithelium overlies tumor situated below this depth of penetration. Another potential confounder is respiratory epithelium in the larynx, which has a greater density of nuclei than typical squamous epithelium, thus making it more difficult to distinguish benign and malignant epithelium (Figure 8(c)). These limitations are active areas of ongoing research into strategies such as alternative contrast agents, quantitative analysis of nuclear morphology and pattern, and submucosal delivery of the fiberoptic probe.

Figure 8.

Current limitations of the HRME. (a) Keratin artifact appears hyperfluorescent, obscuring visualization of the nuclei in benign mucosa from the hard palate (top) and malignant mucosa from the base of tongue (bottom) ( H&E original magnification 100x). (b) Underlying invasive squamous cell carcinoma infiltrating beneath benign squamous epithelium in the larynx (top) and tonsil (bottom) (H&E original magnification 100x). (c) Pseudostratified columnar epithelium of respiratory mucosa from the larynx (H&E original magnification 100x). Notice the relatively crowded nuclei which may be confused with dysplasia or carcinoma.

5. Discussion and Application

Non-invasive optical imaging techniques can enhance discrimination between benign and malignant mucosa in the UADT, with potential applications in early cancer detection, intraoperative margin detection, and image-guided endoscopic ablative therapy. Simple, portable diagnostic modalities such as the HRME, can provide real-time pathological examination of mucosa, since images correlate closely with the gold stand of H&E histopathology. The use of such devices during tumor ablative surgery may allow for more accurate tumor mapping by creation of precise “optical margins” which can direct and minimize the number of conventional “frozen section” determinations. Our group is currently testing the ability of the HRME to discriminate between benign and malignant mucosa in vivo at various locations in the head and neck. If results in vivo parallel the close correlation with conventional histopathology seen in our ex vivo study, we will assess in clinical trials the ability of HRME-directed margin determination to accurately map tumor margins and decrease utilization of frozen section analysis.

With growing emphasis on less invasive and less morbid ablative surgical techniques in the head and neck, such as transoral robotic surgery (TORS) and transoral laser surgery, advanced imaging modalities are likely to play an increasingly important role in directing narrow-margin and minimal access surgery [28]. The development of high-resolution image-guided surgery and other ablative therapies will require that surgeons and endoscopists supplement their formidable knowledge of UADT anatomy with an equally formidable understanding of its histopathological appearance; imaging atlases such as this are an important step towards that goal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to Mount Sinai School of Medicine to fund Clinical Research Fellows Lauren L. Levy and Peter M. Vila, a National Cancer Institute Bioengineering Research Partnership (BRP) Grant 2R01CA103830-06A1 and a competitive research grant from Intuitive Surgical Inc.

Footnotes

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;vol. 332(no. 7):429–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502163320704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haque R, Contreras R, McNicoll MP, Eckberg EC, Petitti DB. Surgical margins and survival after head and neck cancer surgery. BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders. 2006;vol. 6 doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-6-2. article 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamba A, Romano M, Grosso IM, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of patients surgically treated for head and neck cancer. Head and Neck. 1992;vol. 14(no. 3):218–223. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880140309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dropkin MJ. Body image and quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Practice. 1999;vol. 7(no. 6):309–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black C, Marotti J, Zarovnaya E, Paydarfar J. Critical evaluation of frozen section margins in head and neck cancer resections. Cancer. 2006;vol. 107(no. 12):2792–2800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiNardo LJ, Lin J, Karageorge LS, Powers CN. Accuracy, utility, and cost of frozen section margins in head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2000;vol. 110(no. 10):1773–1776. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ord RA, Aisner S. Accuracy of frozen sections in assessing margins in oral cancer resection. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1997;vol. 55(no. 7):663–671. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keereweer S, Sterenborg HJCM, Kerrebijn JDF, VanDriel PBAA, De Jong RJB, Löowik CWGM. Imageguided surgery in head and neck cancer: current practice and future directions of optical imaging. Head and Neck. 2011;vol. 34:120–126. doi: 10.1002/hed.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roblyer D, Richards-Kortum R, Sokolov K, et al. Multispectral optical imaging device for in vivo detection of oral neoplasia. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2008;vol. 13(no. 2) doi: 10.1117/1.2904658. Article ID 024019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roblyer D, Kurachi C, Stepanek V, et al. Objective detection and delineation of oral neoplasia using autofluorescence imaging. Cancer Prevention Research. 2009;vol. 2(no. 5):423–431. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, et al. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;vol. 12(no. 22):6716–6722. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muldoon TJ, Roblyer D, Williams MD, Stepanek VMT, Richards-Kortum R, Gillenwater AM. Noninvasive imaging of oral neoplasia with a high-resolution fiber-optic microendoscope. Head and Neck. 2012;vol. 34(no. 3):305–312. doi: 10.1002/hed.21735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark AL, Gillenwater AM, Collier TG, Alizadeh-Naderi R, El-Naggar AK, Richards-Kortum RR. Confocal microscopy for real-time detection of oral cavity neoplasia. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;vol. 9(no. 13):4714–4721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark A, Collier T, Lacy A, et al. Detection of dysplasia with near real time confocal microscopy. Biomedical Sciences Instrumentation. 2002;vol. 38:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poh CF, MacAulay CE, Zhang L, Rosin MP. Tracing the “at-risk” oral mucosa field with autofluorescence: steps toward clinical impact. Cancer Prevention Research. 2009;vol. 2(no. 5):401–404. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poh CF, Durham JS, Brasher PM, et al. Canadian Optically-guided approach forOral Lesions Surgical (COOLS) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2011;vol. 11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-462. article 462, Article ID 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark AL, Gillenwater AM, Collier TG, Alizadeh-Naderi R, El-Naggar AK, Richards-Kortum RR. Confocal microscopy for real-time detection of oral cavity neoplasia. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;vol. 9(no. 13):4714–4721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White MW, Rajadhyaksha M, González S, Fabian RL, Anderson RR. Noninvasive imaging of human oral mucosa in vivo by confocal reflectance microscopy. Laryngoscope. 1999;vol. 109(no. 10):1709–1717. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199910000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muldoon TJ, Anandasabapathy S, Maru D, Richards-Kortum R. High-resolution imaging in Barrett’s esophagus: a novel, low-cost endoscopic microscope. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2008;vol. 68(no. 4):737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosbach KJ, Shin D, Muldoon TJ, et al. High-resolution fiber optic microscopy with fluorescent contrast enhancement for the identification of axillary lymph node metastases in breast cancer: a pilot study. Biomedical Optics Express. 2010;vol. 1:911–922. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.000911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muldoon TJ, Roblyer D, Williams MD, Stepanek VMT, Richards-Kortum R, Gillenwater AM. Noninvasive imaging of oral neoplasia with a high-resolution fiber-optic microendoscope. Head and Neck. 2012;vol. 34(no. 3):305–312. doi: 10.1002/hed.21735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vila P, Park C, Pierce M, et al. Discrimination of benign and neoplastic mucosa with a high-resolution microendoscope (HRME) in head and neck cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2351-1. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muldoon TJ, Pierce MC, Nida DL, Williams MD, Gillenwater A, Richards-Kortum R. Subcellular-resolution molecular imaging within living tissue by fiber microendoscopy. Optics Express. 2007;vol. 15(no. 25):16413–16423. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.016413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson LR, Denny WA. Genotoxicity of noncovalent interactions: DNA intercalators. Mutation Research. 2007;vol. 623(no. 1–2):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polglase AL, McLaren WJ, Skinner SA, Kiesslich R, Neurath MF, Delaney PM. A fluorescence confocal endomicroscope for in vivo microscopy of the upper- and the lower-GI tract. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;vol. 62(no. 5):686–695. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiesslich R, Burg J, Vieth M, et al. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2004;vol. 127(no. 3):706–713. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssen PA, Selwood BL, Dobson SR, Peacock D, Thiessen PN. To dye or not to dye: a randomized, clinical trial of a triple dye/alcohol regime versus dry cord care. Pediatrics. 2003;vol. 111(no. 1):15–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genden EM, Desai S, Sung CK. Transoral robotic surgery for the management of head and neck cancer: a preliminary experience. Head and Neck. 2009;vol. 31(no. 3):283–289. doi: 10.1002/hed.20972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]