The prevalence of low bone mineral density in premenopausal women treated for gynecological cancer is explored and the direct effect of cancer treatment versus that of hormone withdrawal on the bone health of gynecological cancer survivors is evaluated.

Keywords: Gynecological cancer, Osteoporosis, Bone diseases, Metabolic, Bone density, Survivors

Learning Objectives

Describe the potential contributors to bone demineralization in patients receiving systematic treatment for gynecological malignancies.

Define what is meant by “osteopenia” and “osteoporosis” and describe their relevance to fracture risk.

Explain the importance of preventing and managing bone mineral loss and its complications in gynecological cancer survivors.

Abstract

Background.

An association between treatment for gynecological cancers and risk of osteoporosis has never been formally evaluated. Women treated for these cancers are now living longer than ever before, and prevention of treatment-induced morbidities is important. We aimed to distinguish, in gynecological cancer survivors, whether cancer therapy has additional detrimental effects on bone health above those attributable to hormone withdrawal.

Methods.

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan results from 105 women; 64 had undergone bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) followed by chemotherapy or radiotherapy for gynecological malignancies, and 41 age-matched women had undergone BSO for benign etiologies. All were premenopausal prior to surgery.

Results.

The median age at DEXA scan for the cancer group was 42 years, and 66% had received hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) following their cancer treatment. For the benign group, the median age was 40 years, and 87% had received HRT. Thirty-nine percent of cancer survivors had abnormal DEXA scan results compared to 15% of the control group, with the majority demonstrating osteopenia. The mean lumbar spine and femoral neck bone mineral densities (BMDs) were significantly lower in cancer patients. A history of gynecological cancer treatment was associated with significantly lower BMD in a multivariate logistic regression.

Conclusions.

Women treated for gynecological malignancies with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy have significantly lower BMDs than age-matched women who have undergone oophorectomy for noncancer indications. Prospective evaluation of BMD in gynecological cancer patients is recommended to facilitate interventions that will reduce the risk of subsequent fragility fractures.

Implications for Practice:

In our study, we showed that there is a high prevalence of bone mineral loss in patients treated for gynecological malignancies with the majority of cases having osteopenia, which can easily be reversed if identified and treated early. Our findings suggest that fracture risk assessment should be incorporated into the routine screening of gynecological cancer patients on treatment completion and during follow up. This will enable patient stratification to those at high and low risk for fragility factures. Patients identified as being at high risk should be considered for appropriate dietary supplementation in order to minimize their risk for future fractures and the debilitating consequences on their quality of life.

Introduction

In the U.K., there are now approximately two million cancer survivors, and the number is estimated to be increasing by 3.2% per annum [1, 2]. Advances in earlier cancer detection and treatment have seen steady improvements in survival outcomes for women with gynecological malignancies over the last 30 years [1]. This has led to calls for closer evaluation of the long-term manifestations of cancer treatment and how these might impact morbidity and mortality in survivors [3]. Approximately 30%–40% of women with gynecological cancer are premenopausal or perimenopausal at the time of their diagnosis [4] but undergo an abrupt menopause following initial debulking surgery because their ovaries, along with their other gynecological organs, are removed. The standard postoperative treatment for these women is to receive chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Although reports have been published exploring the long-term physical and psychological consequences of treatment in gynecological cancer survivors [5–8], there is a gap in the existing literature as to the impact of cancer treatment on bone mineral density (BMD) in these patients.

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture [9, 10]. Osteoporosis and osteopenia are associated with a greater fracture risk, estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be 46.6 and 19.6 hip fractures per 1,000 patient years, respectively (compared with 7.6 hip fractures per 1,000 patient years in those with a normal BMD) [11]. In addition to hip fractures, patients with demineralized bone are also at risk for fractures of the vertebrae and wrist and the resultant chronic pain, disability, poor quality of life, and mortality [12–14].

Several risk factors have been associated with bone demineralization, such as increasing age, low body mass index (BMI), excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, corticosteroid treatment, and family history of osteoporosis or fracture [14, 15]. Loss of bone mineralization can also result from other causes, such as osteomalacia, in which low levels of vitamin D impair calcium and phosphate uptake [16, 17]. Early detection of low BMD using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning in high-risk patients allows the introduction of interventions to preserve the remaining bone mass. Adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation, as well as lifestyle changes to incorporate exercise, play a preventative role for bone demineralization [18]. Hormonal replacement treatment (HRT) has also been associated with a lower risk for BMD loss [19]. In the case of established bone demineralization, antiresorptive pharmacological agents such as bisphosphonates and denosumab have been proven to be effective for improving BMD [20–22].

Osteoporosis and osteopenia are well-established consequences of breast and prostate cancer treatment [23–27], and guidelines have been developed to prevent and manage BMD loss in these patients [28–31]. Although gynecological cancer patients who are premenopausal at diagnosis experience treatment-induced menopause following surgical oophorectomy, it is not currently routine practice to screen them for BMD loss on completion of treatment and there is little research into the risk for BMD loss in this patient group. In this study, we aimed to explore the prevalence of low BMD in premenopausal women treated for gynecological cancer and to distinguish between the direct effect of cancer treatment and that of hormone withdrawal on the bone health of gynecological cancer survivors.

Patients and Methods

Participants

We retrospectively identified gynecological cancer patients who had undergone a DEXA scan in the context of routine screening at the Early Menopause Clinic at Queen Charlotte's Hospital, London between 2006–2012. As well as women undergoing menopause for nonmalignant reasons, patients who had completed treatment for a gynecological malignancy but were premenopausal or perimenopausal at diagnosis were referred here. We included in the analysis only those patients who fulfilled the following criteria: (a) diagnosed with gynecological (endometrial, ovarian, fallopian, or cervical) cancer while premenopausal, (b) treated with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) with or without chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, (c) no evidence of disease relapse at the time of DEXA scan, (d) no history of metabolic or inflammatory bone disease or vitamin D deficiency, and (e) no history of chronic or repeated intermittent corticosteroid administration. DEXA scans from age-matched women who had undergone BSO for benign gynecological conditions were identified from the Premature Ovarian Failure database [32] of the Early Menopause Clinic and were used as controls for the purposes of this study.

Methods

Demographic and clinical characteristics for the study patients were collected from electronic records and included age (at diagnosis and at the time of DEXA scanning), cancer type, disease stage, histological type, grade of cancer, type of treatment received, time elapsed from treatment completion to DEXA scan, history of tobacco use and alcohol consumption, family history of osteoporosis, and history of traumatic fracture. Use of HRT was also documented.

DEXA scans were performed as per the standard technique using a GE Lunar Prodigy scanner (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, U.K., http://www.gehealthcare.com), and BMDs of the lumbar spine (L1–L4) and femoral neck were measured along with the T-score and Z-score. Osteoporosis was diagnosed when BMD at the lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) had a T-score ≤−2.5, and osteopenia was diagnosed when −2.5 < T-score ≤ −1.0 [33]. We defined a low BMD as a T-score <−1.0 in either the LS or the FN, as defined by the WHO criteria [34].

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were generated to characterize the study sample in terms of clinicopathological parameters. Normally distributed continuous data were presented as a mean and standard deviation (SD) and skewed data were presented as a median and range. Categorical outcomes were presented as a frequency and proportion. Student's t test, the Mann-Whitney U-test, or the χ2 test was used to examine differences between the groups. Univariate and multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses were used to determine risk factors for lower BMD.

The SPSS statistical package (version 19; IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses. All p values presented are two sided.

Results

Clinicopathological Characteristics

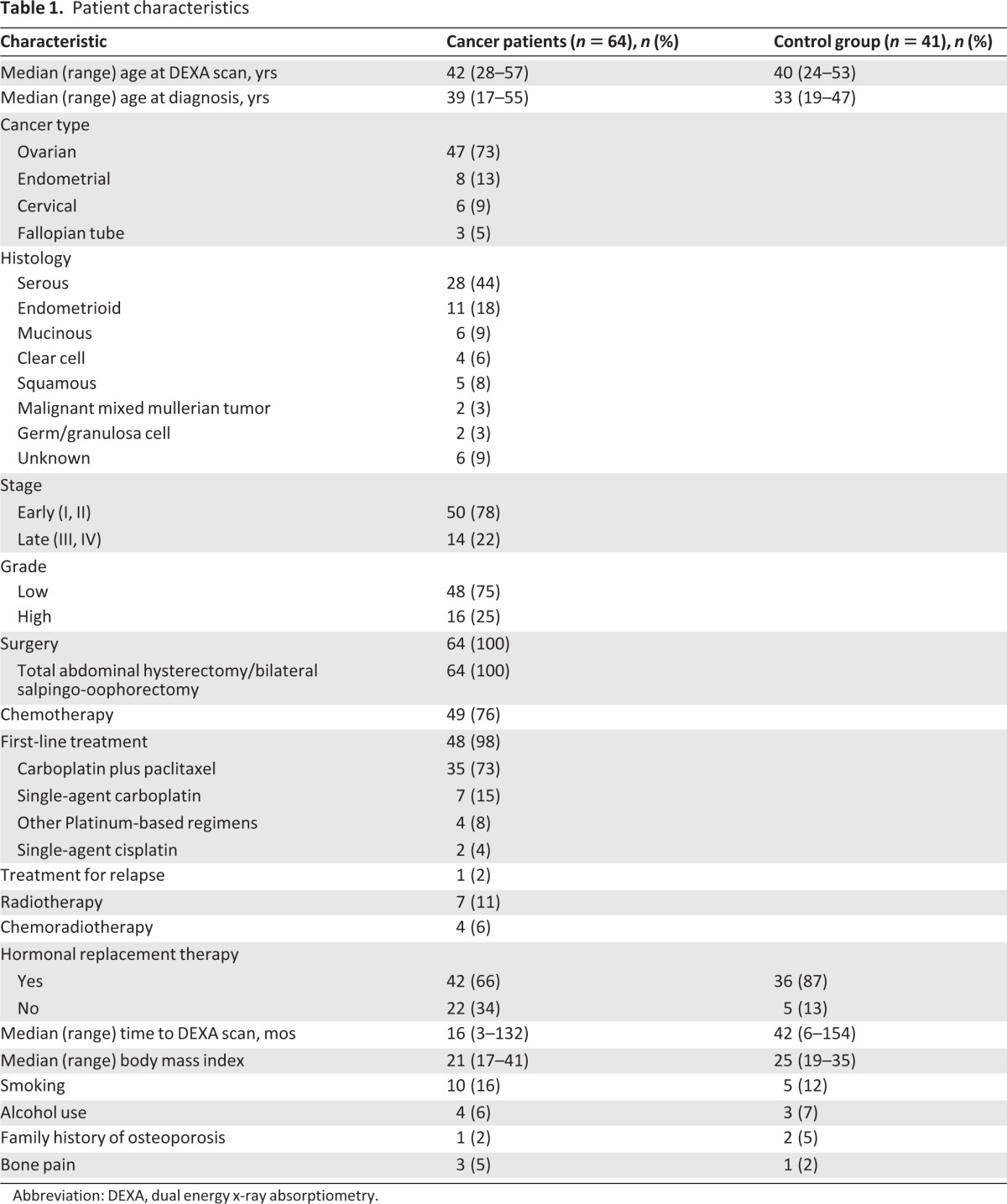

Of the 97 identified gynecological cancer survivors, 64 were included in our analysis: 47 (73%) had ovarian, 8 (13%) had endometrial, 6 (9%) had cervical, and 3 (5%) had fallopian tube cancer. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 39 years (range, 17–55 years), and the median age at the time of DEXA scan was 42 years (range, 28–57 years). Of the cancer patients, 78% had been diagnosed at an early stage (I or II), and the majority (75%) had low-grade malignancies (grade I or grade II). All patients had undergone BSO, 49 (76%) had received adjuvant chemotherapy, which was first line in 48 (98%) of the cases, and 7 patients (11%) had received radiotherapy. Four patients (6%) had received chemoradiotherapy. Forty-two patients (66%) had received HRT by the time of the DEXA scan to control menopausal symptoms. The median BMI was 22 kg/m2 (range, 17–41 kg/m2). Ten patients (16%) had a history of smoking, four patients (6%) had documented alcohol use, one patient (2%) had a family history of osteoporosis, and no patient had suffered previous traumatic fractures.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Abbreviation: DEXA, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry.

The control group was comprised of 41 age-matched women who had undergone BSO for benign conditions, including endometriosis, bilateral benign ovarian cysts, and menorrhagia. The median age at diagnosis was 33 years (range, 19–47 years) and the median age at the time of DEXA scan was 40 years (range, 24–53 years). The median BMI was 25 kg/m2 (range, 19–35 kg/m2). Between the two groups, there was no statistically significant difference for median age at the time of DEXA scan (p = .3) or median BMI (p = .2). Thirty-six patients (87%) in the benign group had received HRT by the time of their DEXA scan. The median time from surgery to DEXA scan was 16 months (range, 3–136 months) for the cancer group and 42 months (range, 6–154 months) for the benign group.

Prevalence of BMD Loss for Each Area of Interest

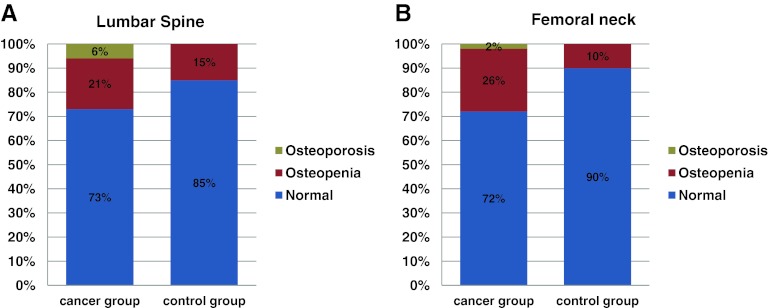

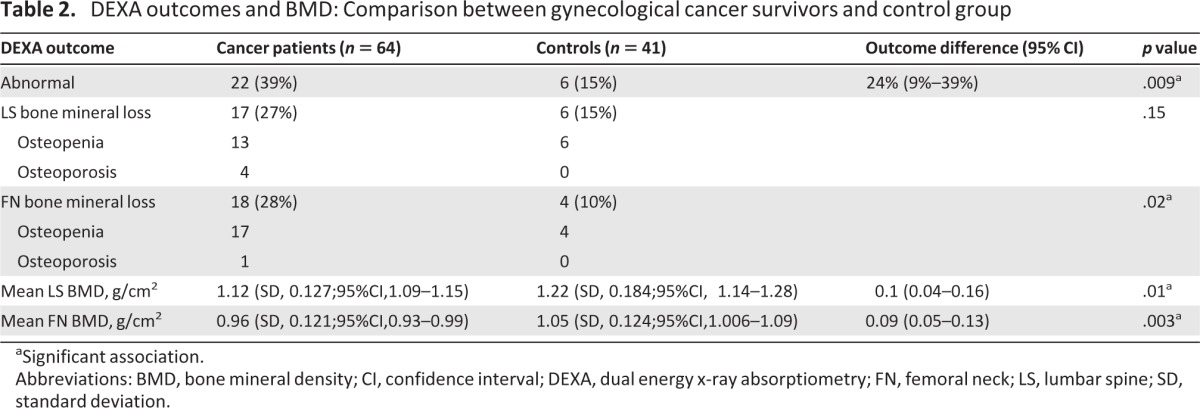

The BMD results for the LS and FN for our study patients are summarized in Table 2 and compared with those of the control group. Thirty-nine percent (95% confidence interval [CI], 27%–51%) of the gynecological cancer patients had an abnormal DEXA scan, compared with 15% (95% CI, 4%–26%) of the control group (p = .009). A difference of 24% (95% CI, 9%–39%) in the prevalence of BMD loss was noted between the two study groups. BMD loss in the LS was identified in 17 (27%) of the cancer patients, of whom 13 (21%) had a diagnosis of osteopenia and four (6%) had a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Bone demineralization in the LS was identified in six individuals (15%) within the benign group, all of whom were osteopenic. BMD loss in the FN was found in 18 (28%) of the cancer patients, with 17 (26%) having osteopenia and 1 (2%) having osteoporosis. Of the benign group, 4 (10%) individuals had bone demineralization in the FN, and all cases had osteopenia (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

DEXA outcomes and BMD: Comparison between gynecological cancer survivors and control group

aSignificant association.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; CI, confidence interval; DEXA, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry; FN, femoral neck; LS, lumbar spine; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Comparative prevalence of bone demineralization in the lumbar spine (A) and femoral neck (B) between gynecological cancer survivors and the control group.

The mean LS BMD of the cancer patients was 1.12 g/cm2 (95% CI, 1.09–1.15 g/cm2; SD, 0.127), compared with 1.22 g/cm2 (95% CI, 1.14–1.28 g/cm2; SD, 0.184) in the benign group (p = 0.01). The mean difference in LS BMD between the two study groups was 0.1 g/cm2 (95% CI, 0.04–0.16 g/cm2). For the FN, the mean BMD was 0.96 g/cm2 (95% CI, 0.93–0.99 g/cm2; SD, 0.121) in the cancer patients and 1.05 g/cm2 (95% CI, 1.006–1.09 g/cm2; SD, 0.124) in the benign group (p = .003). The mean difference in FN BMD between the two groups was 0.09 g/cm2 (95% CI, 0.05–0.13 g/cm2) (Table 2).

Risk Factors for BMD Loss in Gynecological Cancer Survivors

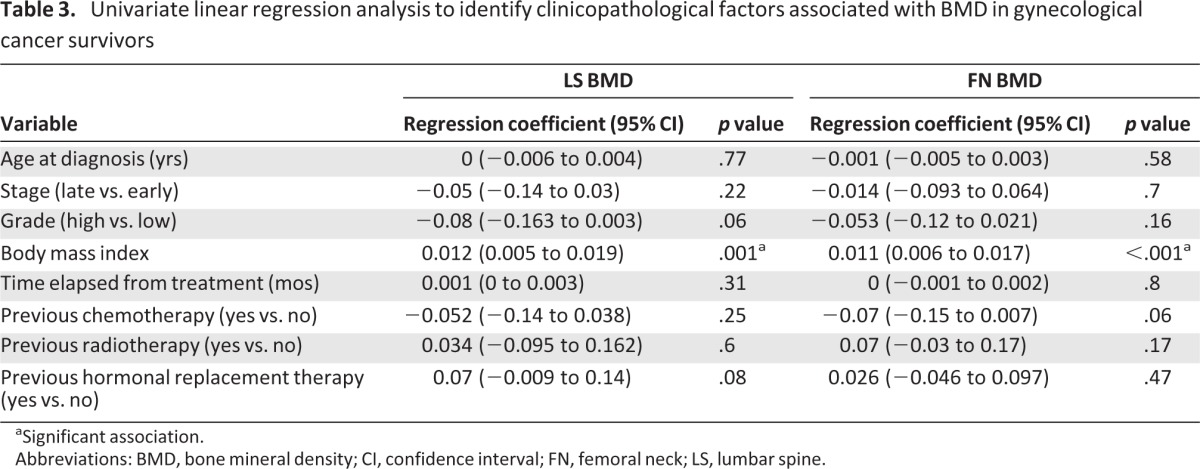

Associations between FN BMD and LS BMD and several clinicopathological factors—such as age at diagnosis, disease stage, grade of cancer, BMI, time elapsed since the end of treatment, and previous treatment—were examined in the gynecological cancer group with the use of univariate and multivariate linear regression. Results are summarized in Table 3. Of the examined factors, only BMI was significantly associated with BMD both for the LS (p = .001) and for the FN (p < .001). In the multivariate linear regression analysis, BMI was identified as the only significant independent factor associated with BMD both in the LS (p = .02) and in the FN (p < .001).

Table 3.

Univariate linear regression analysis to identify clinicopathological factors associated with BMD in gynecological cancer survivors

aSignificant association.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; CI, confidence interval; FN, femoral neck; LS, lumbar spine.

Gynecological Cancer as a Risk Factor for BMD Loss

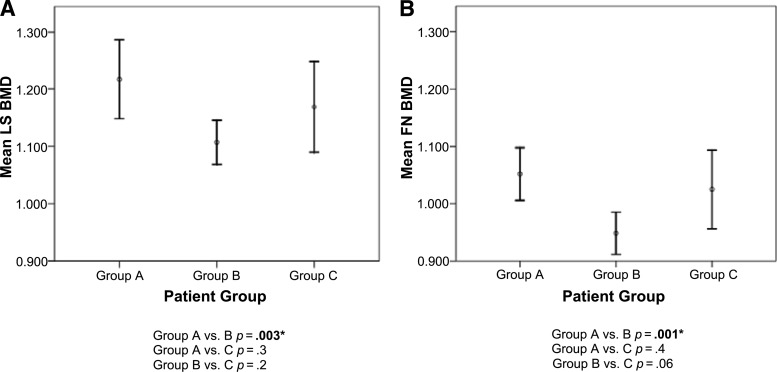

Multivariate logistic regression was performed in the combined population (n = 105) of our study to assess parameters such as gynecological cancer, HRT intake, and time elapsed from surgery as potential risk factors for BMD loss. Gynecological malignancy was identified as the only significant independent risk factor for BMD loss (odds ratio [OR], 4.2; 95% CI, 1.4–12.6; p = .009). Postsurgical use of HRT did not have an independent effect on BMD. We then categorized the study population (n = 105) into three subgroups: those who had undergone surgery for benign etiologies (group A, n = 41; median age, 40 years), those diagnosed with gynecological cancer and treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy (group B, n = 49; median age, 46 years), and those diagnosed with gynecological cancer who had been treated with surgery alone (group C, n = 15; median age, 36 years). There was a statistically significant difference between group A and group B in the mean LS BMD (p = .003) as well as in the mean FN BMD (p = .001) (Fig. 2). No statistical significance was noticed when the mean LS and FN BMDs were compared between group A and group C.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean BMD in the LS (A) and FN (B) among the three study subgroups. Group A consisted of patients who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for a benign etiology (n = 41), group B consisted of patients who underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy for gynecological cancer (n = 49), and group C consisted of patients who underwent only surgical treatment for a gynecological malignancy (n = 15).

*Significant association.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; LS, lumbar spine; FN, femoral neck.

Discussion

The results of this retrospective study show that premenopausal women who undergo surgical menopause and receive surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy treatment for gynecological malignancies have a significantly higher prevalence of bone demineralization than age-matched women who only undergo BSO for benign etiologies. Furthermore, we noted a significantly lower mean LS BMD and FN BMD, by 7.1% and 8.6% respectively, in our gynecological cancer patients compared with the benign group using the same DEXA technique. This places these cancer survivors at a greater risk for osteoporotic fractures in the future.

BSO causes sudden and permanent estrogen withdrawal, which is acknowledged to double the risk for osteoporotic fractures [35]. This is believed to result from the removal of hormonal control over bone homeostasis, causing a shift toward increased osteoclasts and bone resorption [36]. In this study, although the two patient groups were age matched and both had undergone BSO, the prevalence of BMD was significantly greater in the gynecological cancer survivors who had received adjuvant chemotherapy following their surgery. Furthermore, gynecological cancer was identified as a significant independent risk factor for BMD loss in the multivariate analysis performed in the combined study population (OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 1.4–12.4; p = .009). The use of HRT was not identified as an independent risk factor affecting BMD in our analysis. This suggests that there may be nonhormonal factors contributing to the bone demineralization. In our study, 76% of patients had received at least one line of adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy. Those patients were given high doses of corticosteroids during their chemotherapy to suppress emesis and drug hypersensitivity reactions. Corticosteroids have long been associated with bone demineralization by attenuating osteoblast activity [37, 38], with a dose >450 mg of prednisolone administered over a 3-month (12-week) period (equivalent to 5.5 mg of dexamethasone per week) being a significant risk factor for bone loss. The majority of our study patients (61%) were given carboplatin and paclitaxel, which is routinely accompanied by ∼60–80 mg dexamethasone administered per cycle. Thirty-nine percent received single-agent platinum-based chemotherapy, which is accompanied by 44–50 mg dexamethasone per cycle. Over a course of six cycles of chemotherapy (given over 18 weeks), our patients were therefore given 260–480 mg dexamethasone (equivalent to 14–26 mg dexamethasone per week), well over the threshold associated with bone loss. There may also be a negative impact on BMD from chemotherapy itself, beyond the acknowledged chemotherapy-induced gonadal damage. This has previously been described in ovarian cancer patients receiving treatment using a combination of cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy [39], as well as in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer [40].

Another possibility is that the tumor itself may secrete factors that could demineralize bone. Elevated levels of parathyroid hormone-related protein, have been documented in patients with ovarian cancer, although notably in association with hypercalcemia [41]. Other, as yet undocumented, factors released by tumor tissue may exacerbate bone demineralization in these patients.

Dividing the study population into subgroups, we noted that there was no significant difference in the mean LS or FN BMD between those who received only surgical treatment for gynecological cancer and the control group. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the mean FN and LS BMD between patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy and control patients. Although the size of the subgroups was limited, these findings support the multifactorial nature of bone demineralization in gynecological cancer patients and also indicate that systemic cancer treatment, rather than surgery, is the main negative contributor to BMD.

This study was nonprospective, and although patients' medical notes were reviewed, patients were not formally questioned about osteoporosis risk factors (such as smoking and alcohol intake) nor did they undergo “baseline” DEXA scans at the start of their cancer treatment to assess the incremental effects of surgery and chemotherapy on their BMD. In addition, 87% of the controls had received HRT by the time of their DEXA scans, compared with 66% of the cancer patients. To assess the possible influence of this factor, we performed a multivariate regression analysis, which showed that post-surgical use of HRT was not a significant independent risk factor for BMD loss.

We show that there is a significantly higher rate (39%) of osteopenia and osteoporosis in premenopausal patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy for gynecological cancers than in those treated with surgery for benign conditions. In the majority of cases, patients were diagnosed with osteopenia, which, if identified and treated can be easily reversed. However, there are currently no guidelines in place supporting the routine screening of gynecological cancer patients for BMD loss on treatment completion and during follow-up. Our findings suggest that fracture risk should be included in the post-treatment care of gynecological cancer patients, by assessing BMD as well as identifying predisposing clinical and genetic risk factors. Patients who are identified as being at high risk for fractures should be considered for vitamin and calcium supplementation and/or bisphosphonate therapy [22]. When appropriate, patients with an iatrogenic premature menopause should be recommended estrogen replacement as a first-line therapy to prevent postmenopausal bone loss. However, this is controversial in patients with a history of hormone receptor–expressing gynecological tumors because of a perceived higher risk for disease recurrence [42].

Our findings call for a prospective study involving the assessment of BMD before and after gynecological cancer treatment to fully evaluate its effect on bone mineral content. This will enable early implementation of measures to protect gynecological cancer survivors from fragility fractures later on in life.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the patients who participated in this research and the Rosie Williams Charitable Foundation.

This work has been, in part, supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust, Imperial Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre (ECMC), Cancer Research UK (CRUK), and Imperial National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). W.S.D. is funded by an NIHR Career Development Fellowship. S.P.B. is supported by Ovarian Cancer Action and Wellbeing of Women.

Nick Panay and Sarah P. Blagden are considered joint last authors.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Sarah P. Blagden, Chara Stavraka, Nick Panay

Provision of study material or patients: Sarah P. Blagden, Chara Stavraka, Kate Maclaran, Hani Gabra, Roshan Agarwal, Sadaf Ghaem-Maghami, Alexandra Taylor, Nicholas Panay

Collection and/or assembly of data: Sarah P. Blagden, Chara Stavraka, Kate Maclaran

Data analysis and interpretation: Sarah P. Blagden, Chara Stavraka, Hani Gabra, Roshan Agarwal, Waljit S. Dhillo, Nick Panay

Manuscript writing: Sarah P. Blagden, Chara Stavraka, Kate Maclaran, Hani Gabra, Roshan Agarwal, Sadaf Ghaem-Maghami, Alexandra Taylor, Waljit S. Dhillo, Nick Panay

Final approval of manuscript: Sarah P. Blagden, Chara Stavraka, Waljit S. Dhillo, Nick Panay

Disclosures

Nick Panay: Pfizer, Bayer, Abbott (C/A); Bayer (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section editors: Dennis Chi: None

Peter Harper: Sanofi, Roche, Imclone, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Genentech (C/A); Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche (H)

Reviewer “A”: None

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK. CancerStats: Cancer Statistics for the UK. [accessed September 15, 2012]. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats.

- 2.Maddams J, Brewster D, Gavin A, et al. Cancer prevalence in the United Kingdom: Estimates for 2008. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:541–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lustberg MB, Reinbolt RE, Shapiro CL. Bone Health in Adult Cancer Survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3665–3674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher EJ, Denton A. Survivorship, late effects and cancer of the cervix. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, et al. Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: Psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaz AF, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM, et al. Quality of life and menopausal and sexual symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors: A cohort study. Menopause. 2011;18:662–669. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ffde7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stavraka C, Ford A, Ghaem-Maghami S, et al. A study of symptoms described by ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Consensus development conference: Diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1993;94:646–650. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90218-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cranney A, Jamal SA, Tsang JF, et al. Low bone mineral density and fracture burden in postmenopausal women. CMAJ. 2007;177:575–580. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey N, Dennison E, Cooper C. Osteoporosis: Impact on health and economics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:99–105. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanis JA World Health Organisation Scientific Group. Technical Report 2008. Sheffield, UK: WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Sheffield; 2008. Assessment of Osteoporosis at the Primary Health-Care Level; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(suppl 6):1689S–1696S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winters-Stone KM, Dobek J, Nail LM, et al. Impact + resistance training improves bone health and body composition in prematurely menopausal breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2012 Sep 21; doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2143-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Challberg J, Ashcroft L, Lalloo F, et al. Menopausal symptoms and bone health in women undertaking risk reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: Significant bone health issues in those not taking HRT. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:22–27. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rachner TD, Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet. 2011;377:1276–1287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62349-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756–765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro CL, Halabi S, Hars V, et al. Zoledronic acid preserves bone mineral density in premenopausal women who develop ovarian failure due to adjuvant chemotherapy: Final results from CALGB trial 79809. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:683–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeilschifter J, Diel IJ. Osteoporosis due to cancer treatment: Pathogenesis and management. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1570–1593. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramaswamy B, Shapiro CL. Osteopenia and osteoporosis in women with breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:763–775. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brufsky AM. Cancer treatment-induced bone loss: Pathophysiology and clinical perspectives. The Oncologist. 2008;13:187–195. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickham R. Osteoporosis related to disease or therapy in patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:E90–E104. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.E90-E104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guise TA. Bone loss and fracture risk associated with cancer therapy. The Oncologist. 2006;11:1121–1131. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-10-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel-Razeq H, Awidi A. Bone health in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7:256–263. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.87006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Body JJ, Bergmann P, Boonen S, et al. Management of cancer treatment-induced bone loss in early breast and prostate cancer—a consensus paper of the Belgian Bone Club. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1439–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michaud LB. Managing cancer treatment-induced bone loss and osteoporosis in patients with breast or prostate cancer. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(suppl 3):S20–S30. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadji P, Gnant M, Body JJ, et al. Cancer treatment-induced bone loss in premenopausal women: A need for therapeutic intervention? Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maclaran K, Panay N. Premature ovarian failure. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2011;37:35–42. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc.2010.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO Study Group. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: Synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4:368–381. doi: 10.1007/BF01622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svanberg L. Effects of estrogen deficiency in women castrated when young. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1981;106:11–15. doi: 10.3109/00016348209155324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syed F, Khosla S. Mechanisms of sex steroid effects on bone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:688–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canalis E. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:454–457. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200307000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patschan D, Loddenkemper K, Buttgereit F. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Bone. 2001;29:498–505. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00610-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douchi T, Kosha S, Kan R, et al. Predictors of bone mineral loss in patients with ovarian cancer treated with anticancer agents. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:12–15. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadji P, Ziller M, Maskow C, et al. The influence of chemotherapy on bone mineral density, quantitative ultrasonometry and bone turnover in pre-menopausal women with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3205–3212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujino T, Watanabe T, Yamaguchi K, et al. The development of hypercalcemia in a patient with an ovarian tumor producing parathyroid hormone-related protein. Cancer. 1992;70:2845–2850. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921215)70:12<2845::aid-cncr2820701221>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King J, Wynne CH, Assersohn L, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and women with premature menopause—a cancer survivorship issue. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1623–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]