In this study, the impact of a home-based walking intervention during cancer treatment was evaluated. Patients who exercised during cancer treatment experienced less emotional distress than those who were less active. Exercise was also associated with less fatigue and more vigor.

Keywords: Exercise, Walking, Emotional distress, Fatigue, Vigor, Cancer treatment

Learning Objectives

Describe the benefits and limited risks of a low-cost, home-based exercise program.

Impart to patients information on an easily implemented, sustainable, at-home exercise intervention.

Abstract

Purpose.

Exercise use among patients with cancer has been shown to have many benefits and few notable risks. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a home-based walking intervention during cancer treatment on sleep quality, emotional distress, and fatigue.

Methods.

A total of 138 patients with prostate (55.6%), breast (32.5%), and other solid tumors (11.9%) were randomized to a home-based walking intervention or usual care. Exercise dose was assessed using a five-item subscale of the Cooper Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study Physical Activity Questionnaire. Primary outcomes of sleep quality, distress, and fatigue were compared between the two study arms.

Results.

The exercise group (n = 68) reported more vigor (p = .03) than control group participants (n = 58). In dose response models, greater participation in aerobic exercise was associated with 11% less fatigue (p < .001), 7.5% more vigor (p = .001), and 3% less emotional distress (p = .03), after controlling for intervention group assignment, age, and baseline exercise and fatigue levels.

Conclusion.

Patients who exercised during cancer treatment experienced less emotional distress than those who were less active. Increasing exercise was also associated with less fatigue and more vigor. Home-based walking is a simple, sustainable strategy that may be helpful in improving a number of symptoms encountered by patients undergoing active treatment for cancer.

Implications for Practice:

Regular exercise is a low-cost, low-tech way to boost overall well-being among healthy women and men of all ages. In this controlled study, the authors found that ongoing exercise also benefits adults, ages 20–80, in treatment for first-time prostate, breast, and other cancers. A 30-minute brisk walk, 5 days each week—all that's required is a pair of comfortable shoes—can help reduce the emotional distress and fatigue that may accompany chemotherapy, radiation, and other cancer treatments, many of which may often be debilitating. Feeling better promotes getting better. One challenge, however, is for patients to sustain activity, as adherence was an ongoing issue in the study. What makes the study notable is that while prior studies focused on individuals with specific forms of cancer, this study included patients with different cancers as well as patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Introduction

Advances in cancer treatment have extended patient survival, but treatment continues to have a number of immediate and long-term side effects, including sleep disturbances, emotional distress, and fatigue. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF), defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Fatigue Practice Guidelines as “a distressing persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning” [1], is the most frequently reported unmanaged symptom of cancer patients receiving therapy with a prevalence of 50%–100%. Emotional distress and disturbances in sleep quality are also commonly reported [2–5]. Left untreated, these side effects can lead to a marked decrease in physical activity, muscle and bone mass, cardiorespiratory fitness, and increased pain, resulting in treatment delay or drug dose reductions [6]. Both the side effects of treatment and physical inactivity secondary to treatment can decrease physical functioning status and affect quality of life. Thus, identifying effective, low-cost, easily maintained, and feasible activities that patients can use to manage symptoms and maintain functional status is clinically important.

Physical limitations exacerbated during cancer treatment may continue beyond treatment completion if no actions are taken to counteract their effects [7, 8]. In the management of CRF, exercise has considerable support in terms of effectiveness [1]. Individualized exercise programs have also been helpful in preserving or improving physical and cardiorespiratory fitness either during or after cancer treatment [9–15], and home-based exercise programs have demonstrated beneficial effects on fatigue, physical functioning, mood, sleep, and quality of life for these patients [16–18]. However, prior studies have been limited by focusing on single diagnoses, usually breast or prostate cancer [12–15], excluding patients undergoing chemotherapy [19], small samples, or reliance on supervised exercise programs [19–21]. To address this knowledge gap, the primary aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that participants with solid tumors receiving radiation and/or adjuvant chemotherapy who participated in a home-based walking exercise intervention would demonstrate improved sleep quality, better emotional well-being, and lower levels of fatigue when compared to participants who were not offered the intervention.

Patients and Methods

The study population included individuals aged 21 and older with new diagnoses of any type of stage I–III solid malignant tumor who were scheduled to receive either chemotherapy, radiation, or both at three hospital-affiliated treatment sites. The addition of other frequently occurring cancer diagnoses besides breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer in our study was designed to achieve wider clinical applicability of study results and include the most common treatments seen in actual clinical practice (radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and combined modality therapy) [22]. Exclusion criteria included comorbidities such as metastatic cancer, hematologic malignancies, concurrent major health problems or disabilities that would limit participation in an exercise program (e.g., gross obesity [body mass index ≥35 kg/m2]), cardiovascular disease (e.g., angina, myocardial infarction within last 6 months, congestive heart failure), acute or chronic respiratory disease, and cognitive dysfunction that could preclude the advisability or safety of a moderate-intensity walking program. Individuals who reported exercising more than 120 minutes per week were also excluded.

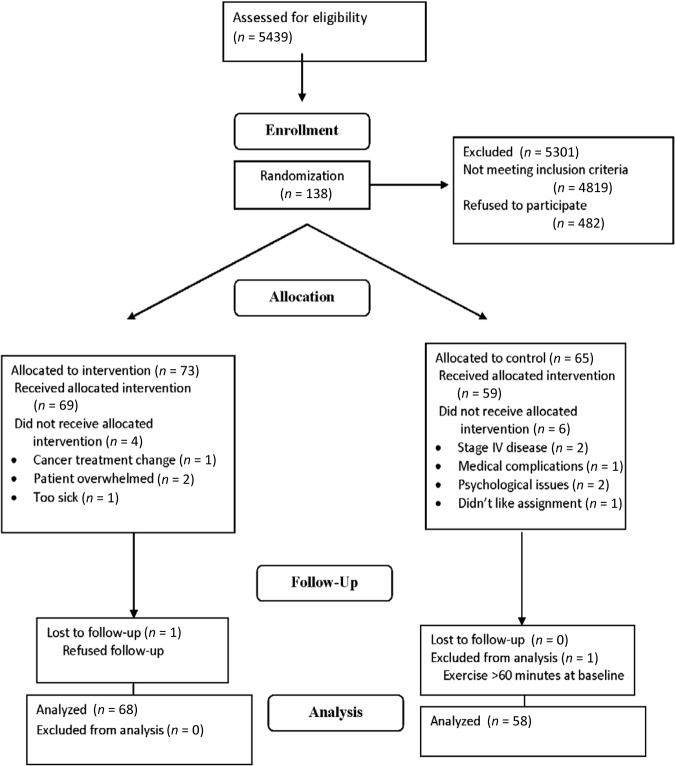

Potential participants were identified from lists in radiation and medical oncology clinics and were screened by telephone interview based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. As detailed in Figure 1 and procedures that have been previously described [23], 138 participants signed informed consent forms and were randomized to the study groups. After enrollment and randomization, 12 participants withdrew, leaving 126 participants who completed the study.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

Following enrollment, participants were randomly assigned to either the usual care group or the exercise group. After random assignment, baseline information was collected for participants in both groups including baseline habitual activity, fatigue level, emotional distress, and sleep quality. Participants' baseline physical function was also measured by either a treadmill test or 12-minute walking test, depending on the study site and participants' preferences. Test results from both testing methods were converted to a standardized score [23]. After the baseline assessment, the two groups began their assigned programs, which were prescribed to continue concurrently with their cancer treatment. Because of the variety of cancer treatment protocols, the total study durations vary from participant to participant, ranging from 5 to 35 weeks. Participants in the usual care group were instructed to maintain their usual physical activity; participants in the exercise group were given an individualized exercise prescription following an initial assessment of physical status and fitness levels.

Data collection started in October 2002 and ended in October 2006. The study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The exercise intervention consisted of the walking prescription, detailed in the booklet, Every Step Counts: A Walking Exercise Program for Persons Living With Cancer [24]. A video emphasizing points in the booklet and standardizing the teaching was provided to all participants in the exercise group. The exercise program was based on American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines and is consistent with exercise recommendations for populations with chronic disease [25]. The targeted exercise prescription for the exercise group was a brisk 20- to 30-minute walk with a 5-minute warm-up period and a 5-minute cool-down period 5 days per week. Exercise was prescribed to reach approximately 50%–70% of maximum heart rate [26, 27]. If participants were unable to reach this goal, they were instructed to begin with a slower pace of two sessions of 5–10 minutes per day and gradually progress to a continuous walk. Exercise participants were asked to wear pedometers daily throughout the whole study period and to record pedometer steps on a daily exercise log. The usual care group participants also completed a daily exercise log but only wore pedometers for the first and last 2 weeks of the study participation period to prevent potential measurement confounding effects, such as having the pedometer use result in greater exercise involvement. Participants in both groups were instructed to mail their exercise logs to the research nurse on a weekly basis.

Instruction for the program took place at the clinical site where research nurses went through the information with participants in both groups, including teaching them how to measure maximum heart rate, but the walking exercise was implemented at home. Throughout the study period, participants in both the exercise and usual care groups received phone contact from research nurses on a biweekly basis to discuss physical activity, cancer treatment, side effects, and any concerns occurring in the previous 2 weeks. For exercise participants, adjustments to the walking prescription were made according to participants' reported conditions. Participants were asked to keep daily diaries of exercise periods with pulse rates, perceived exertion rates, daily fatigue levels, and subjective responses to the intervention (exercise). They were also provided with a list of precautions and signs/symptoms to report to their study nurses. Potential barriers to walking were discussed with participants and workable resolutions were sought (e.g., during snowy or rainy weather, walking in a mall, large public building, or the hospital just prior to daily radiation therapy). The usual care participants received similar biweekly telephone calls. Usual care participants were asked to maintain their current levels of activity. For those who reported actively exercising in the previous 2 weeks, their exercise levels were documented by the study nurses, but no specific exercise advice was offered. Participants in both groups received usual health care provided by their own oncology team.

Adherence to the exercise prescription was defined as walking at least a total of 60 minutes and at least three sessions weekly for more than two thirds of the total number of weeks of each participant's cancer treatment. A daily session was counted by either one continuous exercise session of 20–30 minutes a day, or two sessions of 5–10 minutes for those unable to achieve the 20–30 minutes preferred exercise goal. These criteria are in accordance with guidelines of the ACSM and National Comprehensive Cancer Network [1, 28, 29]. Usual care participants who walked more than 60 minutes/week and participated in more than three sessions weekly for more than two thirds of their treatment weeks were considered nonadherent to their study assignment. Specific issues related to adherence are reported elsewhere [30].

Outcome Measures

Fatigue was measured by the modified Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS) [31], a 22-item 10-point Likert-type self-report scale that measures overall fatigue and four dimensions of subjective fatigue: temporal, severity, affective, and sensory. The PFS is a comprehensive instrument and has reported validity in many studies conducted among patients with cancer [31]. Emotional distress was measured by the Profile of Mood States Scale (POMS), which measures participants' mental/psychological status [32]. The POMS shortened version, containing 30 of the original 65 items, is an adjective rating form composed of subscales that assess six emotional dimensions: anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion. Sleep disturbance was measured by the 21-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality (PSQI) Scale, which has documented validity and reliability [33].

Exercise dose was measured using a five-item subscale of the Cooper Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study Physical Activity Questionnaire (PAQ), a 15-item scale that assesses degree of participation in moderate or vigorous exercise activities during the previous month [34]. Five items were chosen to reflect aerobic activity: walking, jogging, running, swimming, and biking. The questionnaire assigns metabolic equivalent (MET) values to the reported activities to derive MET hours expended per week [35]. Although the focus of the study is on prescribed walking for the intervention group, some participants performed other aerobic activities as a substitute for or as a supplement to walking. As such, these five activities were included as components of the PAQ score and are referenced as PAQFA. New Horizons Digi-Walker pedometers were used to confirm the PAQ and the exercise logs in which participants in both groups recorded exercise frequency and level [36]. Secondary study measures, cardiorespiratory fitness assessed as peak maximal oxygen uptake (VO2), self-reported physical function, and pain have been previously reported [23]. In the dose-response analysis, the percent change of peak VO2 between prostate and nonprostate cancer participants when adjusted for baseline peak VO2 and PAQ values was 17.45% (p = .008). Patients with prostate cancer experienced improved peak VO2 at a nearly 8% increase, whereas those in the nonprostate cancer group suffered a more than 9% loss (percentages have been adjusted for model covariates) [23].

Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analyses

Based on expected medium to large effect sizes reported from baseline to exercise completion for a study with similar reported outcomes [10], the study was originally powered at >0.80 (α = 0.05) with a sample size of 60 for each study group to show group differences on fatigue. Descriptive statistics were calculated for those who completed the study and for those who withdrew. The primary analyses included intent-to-treat (ITT) in which group comparisons were made regardless of the degree of adherence to their assigned group's protocol. Unadjusted ITT comparisons of pre- and post-test outcomes between the two treatment arms were made with t tests.

To adjust for the effect of participants crossing over to the nonprescribed intervention, two types of secondary analyses were performed [30]. We chose these analyses based on other studies in which crossover occurred [7, 37]. A dose-response analysis evaluated outcomes adjusting for the actual amount of exercise performed, regardless of group assignment. Regression analyses, controlled for demographics, pretest outcome score, and exercise level (dose) were conducted to estimate the effect of exercise treatment on post-test outcomes. Weeks of treatment were also controlled for but were not included in the final model due to the absence of impact on the outcomes. Although analysis of change from baseline was also performed, there were no significant differences, so the results are not reported.

Two-tailed tests of significance were performed for all analyses. All analyses were performed using STATA v10.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). An analysis of instrumental variables with principal stratification (IV/PS) using the same set of outcomes and covariates was performed to estimate the intervention effect among participants who would comply with randomization regardless of the intervention group assignment [38]. Because of the large number of patients with prostate cancer in this study, who differed from the rest of our participants in terms of cancer treatment and gender and may have experienced fewer treatment symptoms at a different level, additional analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of cancer type (prostate versus other) on study outcomes.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

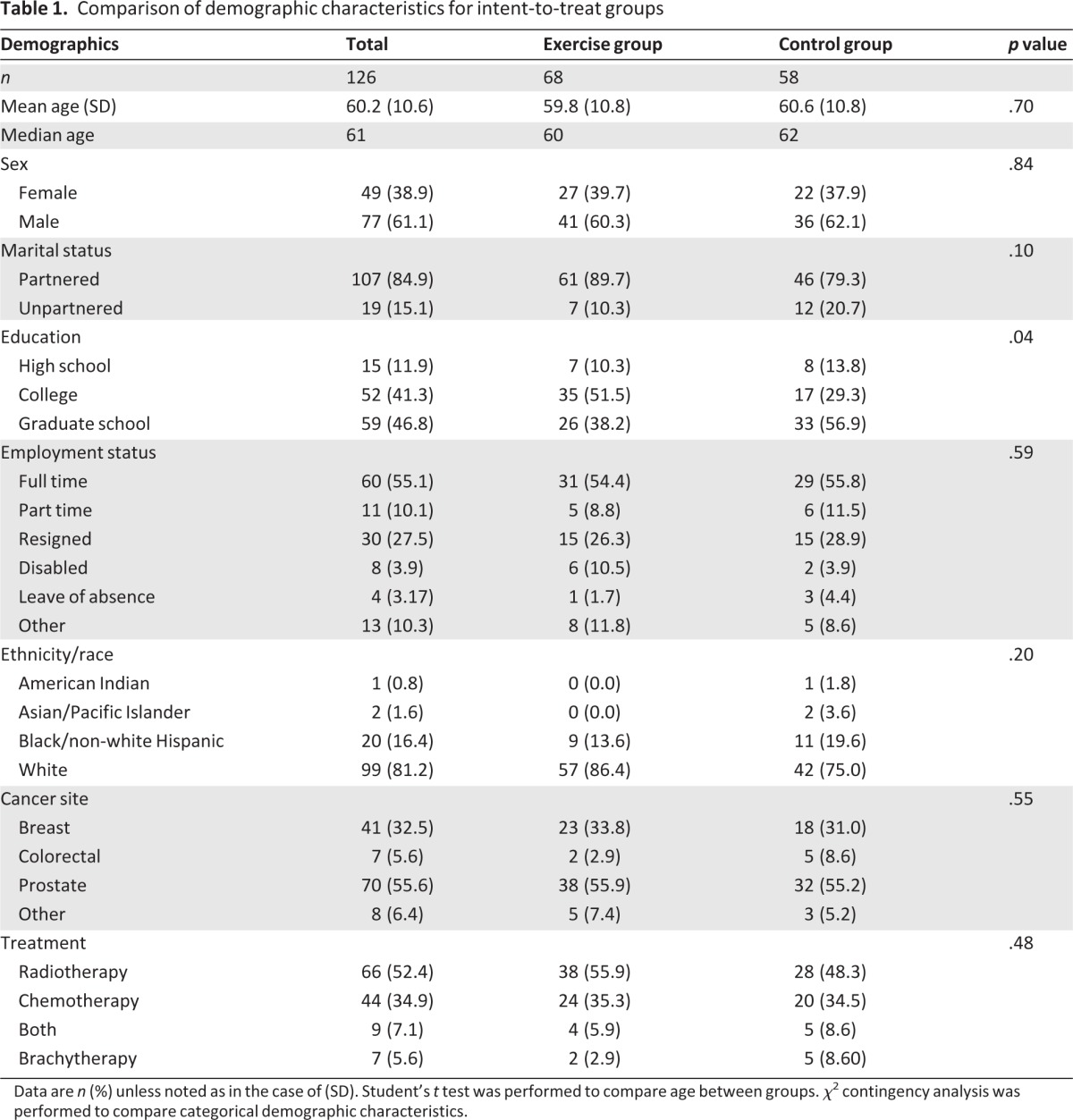

The final study sample has been described previously [23]. It included 126 participants who had a mean age of 60.2 years (range: 28–80 years; SD: 10.6) and were predominantly white (78.6%), male (61.1%), and partnered (married or cohabiting; 84.9%). The most common diagnoses were prostate (55.6%) and breast cancer (32.5%); 5.6% of the sample had colorectal cancer. Participants were undergoing treatment with external beam radiation therapy (52.3%), chemotherapy (34.9%), combined chemotherapy and radiation (7.1%), or brachytherapy alone (5.6%). A demographic table describing the two groups is provided (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics for intent-to-treat groups

Data are n (%) unless noted as in the case of (SD). Student's t test was performed to compare age between groups. χ2 contingency analysis was performed to compare categorical demographic characteristics.

Participants who completed the study were compared with dropouts on age, weight, cancer diagnosis, cancer stage, cancer treatment, race, and highest education level. Patients who withdrew had less educational years (14.8 years; SD=3.5) than those who completed the trial (16.7 years, SD=2.7; p = .029). A higher proportion of ethnic minorities withdrew from the study (18.1%) than Caucasians (5.6%; p = .02). No significant differences were noted between exercise and usual care groups except for education, for which a larger percentage of individuals in the exercise group had college experience or higher. There were no significant differences in baseline outcome measures between the two groups (Table 2).

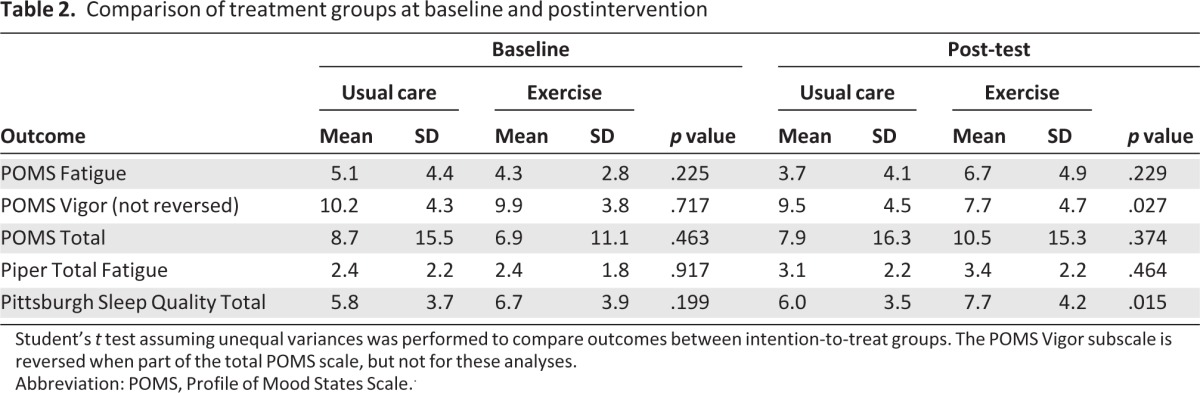

Table 2.

Comparison of treatment groups at baseline and postintervention

Student's t test assuming unequal variances was performed to compare outcomes between intention-to-treat groups. The POMS Vigor subscale is reversed when part of the total POMS scale, but not for these analyses.

Abbreviation: POMS, Profile of Mood States Scale..

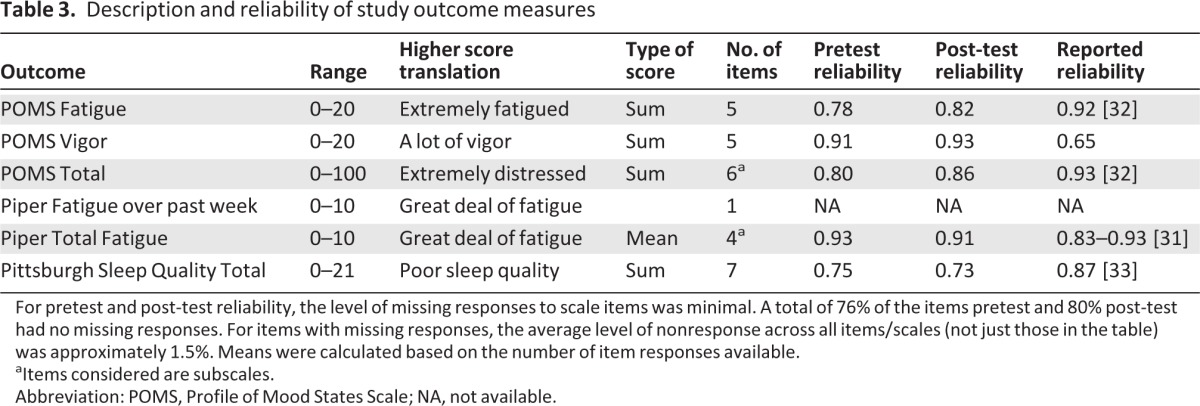

Reliability of Measures

Cronbach's α for scale reliability was estimated for each outcome measure with more than one item at the pre- and postintervention administrations, indicating acceptable reliability of the measures among study participants (Table 3). Spearman correlation between the post-test PAQ and exercise participants' final 5 weeks of pedometer data was calculated; PAQ results were moderately correlated with pedometer data (Spearman ρ = 0.37, p= .002). This shows reasonable acceptability of the PAQ as a measure of exercise, especially because pedometer data were generally underreported based on participants' reports that they did not remember to wear the pedometer consistently.

Table 3.

Description and reliability of study outcome measures

For pretest and post-test reliability, the level of missing responses to scale items was minimal. A total of 76% of the items pretest and 80% post-test had no missing responses. For items with missing responses, the average level of nonresponse across all items/scales (not just those in the table) was approximately 1.5%. Means were calculated based on the number of item responses available.

aItems considered are subscales.

Abbreviation: POMS, Profile of Mood States Scale; NA, not available.

Study Outcomes

Sleep Quality

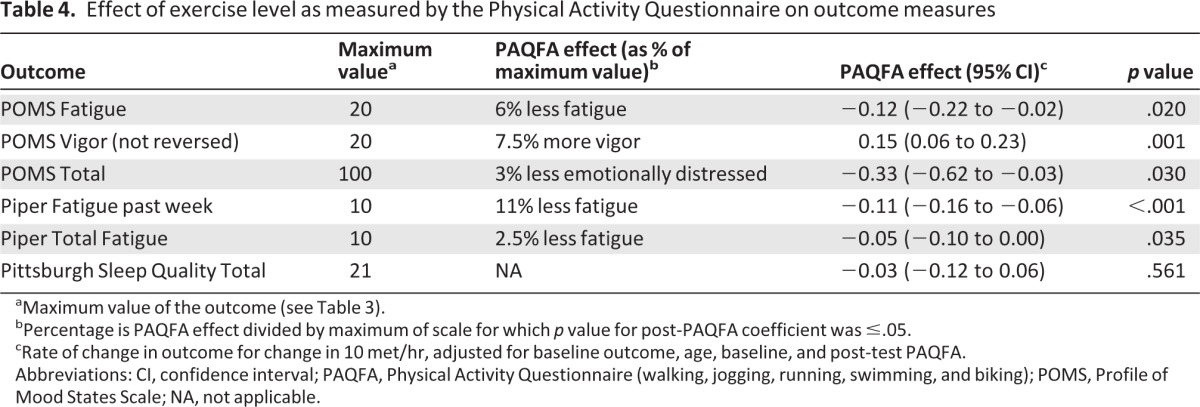

Sleep quality was measured by the PSQI. Overall, participants reported mild sleep disturbances at baseline; however, no difference between the exercise and usual care groups was found at this time point. Although all participants' sleep disturbance increased slightly over the study period, the ITT analysis (Table 2) showed that exercise group participants (mean: 7.7, SD: 4.2) had worse sleep quality (p = .015) than usual care group participants (mean: 6.0, SD: 3.5) at the end of the study. However, when adjusted for exercise and baseline outcome measures, the sleep quality for both groups was not significantly different (p = .6; Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of exercise level as measured by the Physical Activity Questionnaire on outcome measures

aMaximum value of the outcome (see Table 3).

bPercentage is PAQFA effect divided by maximum of scale for which p value for post-PAQFA coefficient was ≤.05.

cRate of change in outcome for change in 10 met/hr, adjusted for baseline outcome, age, baseline, and post-test PAQFA.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PAQFA, Physical Activity Questionnaire (walking, jogging, running, swimming, and biking); POMS, Profile of Mood States Scale; NA, not applicable.

Emotional Distress

As measured by the POMS total score, the mean emotional distress for the entire sample was 7.7 (SD: 13.3) at baseline and did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 2). Over the cancer treatment period, emotional distress for participants in both groups increased slightly, ending with an overall mean emotional distress score of 9.3 (SD: 15.7). There was no significant difference (p = .37) between the usual care mean post-test score of 7.9 (SD: 16.3) and exercise mean score of 10.5 (SD: 15.3); however, the dose-response analysis showed that participants who exercised more had less emotional distress (p = .030) than their counterparts (Table 4).

Fatigue

Using the PFS, the mean fatigue score for the entire group was 2.7 (SD: 2.3) at baseline, ending with a mean fatigue score of 3.8 (SD: 2.7). In the ITT analysis (Table 2), there was no significant difference in fatigue between the exercise and usual care groups. The dose-response analysis (Table 4) indicated that participants who reported more aerobic exercise, regardless of group assignment, had significantly lower fatigue scores: PFS total fatigue (p = .035) and POMS fatigue subscale (p = .020). At the end of their study period, participants who had engaged in more aerobic exercise self-reported less fatigue over the prior week as measured on the PFS past week (p < .001) than participants who had engaged in less aerobic exercise. Furthermore, exercise participants were also found to have more post-test vigor (p = .027) as measured by the POMS vigor subscale, compared with the usual care group (Table 2). Participants who exercised more over the study period had more vigor (p = .001) than those who were sedentary (Table 4). IV/PS results were consistent with the ITT analysis and thus are not reported.

Prostate Versus Nonprostate Participants

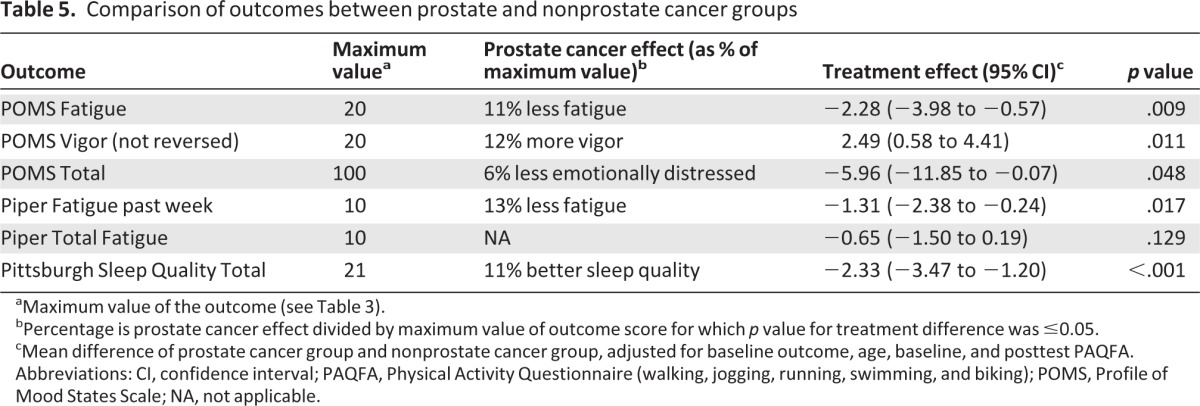

Over half of the study participants had prostate cancer; these participants experienced fewer overall treatment-related symptoms than nonprostate cancer participants (participants with breast or colorectal cancer), including better sleep quality (p < .001), less emotional distress (p = .048), less fatigue (p = .009), and more vigor (p = .011) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of outcomes between prostate and nonprostate cancer groups

aMaximum value of the outcome (see Table 3).

bPercentage is prostate cancer effect divided by maximum value of outcome score for which p value for treatment difference was ≤0.05.

cMean difference of prostate cancer group and nonprostate cancer group, adjusted for baseline outcome, age, baseline, and posttest PAQFA.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PAQFA, Physical Activity Questionnaire (walking, jogging, running, swimming, and biking); POMS, Profile of Mood States Scale; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Key findings from this study suggest that patients who exercised during cancer treatment experience significantly less emotional distress, less fatigue, and more vigor than those who were less active. These findings also correspond to self-reported physical function outcomes previously reported: those participants who engaged in more aerobic exercise were found to have better self-reported physical function (p = .037) and less pain (p = .046) than those who were less active [23]. Participants with a variety of cancer diagnoses were included, demonstrating that a low-cost and flexible home-based exercise program can provide benefits attainable for many patients. Moreover, an exercise dose of at least 60 minutes over three weekly sessions most treatment weeks was established as a feasible goal for patients with cancer undergoing active treatment.

However, as reported in other studies [22, 39], exercise adherence was a challenge in this study. Exercise adherence rates among patients with cancer on active treatment have previously been reported to be between 62% and 90%, with an average of 78% [22, 39, 40]. Previous literature has reported that 22%–52% of control group participants exercised during the study period [22, 40]. In this study, there was a noted exercise crossover effect in both groups, in which 32.4% of participants assigned to exercise “dropped out” and 12% of controls “dropped in” to exercise [30]. Although attention to the control group, in the form of study nurse contact, may have increased contamination slightly, it is notable that our contamination rate is actually lower than that reported in other studies [30]. Low adherence rates have the potential to mask a small but clinically important effect size, attenuating the estimated effect in the ITT analysis. In a post-hoc power analysis, the smallest effect size that we could have detected in the PFS when performing our unadjusted ITT analysis on participants who were both adherent to study assignment and completed study post-tests is 1.79 (power = 0.80, α = 0.05; n = 46 and 51 in the exercise and usual care groups, respectively). Finally, because we did not have the opportunity to collect or review information on those patients who refused to participate, generalizability of findings is limited.

Introduction of prostate cancer treatment advances, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy or intensity-modulated helical tomotherapy occurring concurrently with the study, may have decreased overall side effects of treatment, particularly due to the large number of prostate cancer participants enrolled. This was demonstrated among our participants receiving prostate cancer treatment who reported higher sleep quality (p < .001), lower emotional distress (p = .048), and fatigue (p = .009), along with greater vigor (p = .011), as shown in Table 5; these improved symptoms, experienced by a high percentage of our study population when compared to participants receiving breast or colorectal cancer treatment, may have limited our ability to find statistically significant benefits from the exercise intervention.

As therapies improve and patients experience fewer and less intense treatment side effects, the potential effect attributable to the intervention is threshold-based due to the small difference between the control group levels and the most favorable levels possible. In cases where the observed mean scores are near the extreme end of an instrument scale, the possibility for the intervention group to demonstrate a clinically relevant improvement is limited. Furthermore, overreporting and underreporting of physical activity can hinder accurate effect estimation in the dose-response analysis, affecting the ability to detect an intervention effect. Finally, detecting a clinically significant effect size is further complicated in the presence of nonadherence, a common occurrence in physical activity trials [5, 30, 41].

Trial strengths include implementation of a sustainable at-home exercise intervention that can be easily replicated by patients as well as by researchers in subsequent studies. Although the literature supporting the benefits of exercise continues to grow, much of it is restricted to patients with single diagnoses such as breast and prostate cancer [13–17, 20, 42–46]. The present study, which included patients with a variety of cancer diagnoses, including a modest number of patients with colorectal cancer who have not been previously included in many exercise trials, adds to a growing evidence base that a home-based exercise program has few risks and potential benefit for expanded patient groups. Benefits may include decreased emotional distress and fatigue as well as improved vigor which may be attainable for solid tumor patients, regardless of diagnosis. Exercise has been proposed to affect sleep and mood through fatigue due to the close association of these symptoms [47], and the improvement of fatigue, mood, and sleep together have been documented in other studies [48, 49]. Future intervention studies among patients receiving active cancer treatment should evaluate exercise guidelines specific to age or treatment type and, possibly, cancer diagnosis.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals who contributed to either the study or to manuscript development, including study staff: Sue Hall, Amy Bositis, Karin Holt, Grace Lin, Sharon Kozachik, Christine St. Ours, Theresa Swift-Scanlon, Ph.D., R.N.; Editor Quin Brunk, Ph.D., R.N.; and all study participants.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Nursing Research (NIH 1 R01 NRO 4991 to V.M.) and the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR 025005), the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research, and the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing Center for Collaborative Intervention Research. Funding for the Center is provided by the National Institute of Nursing Research (P30 NRO 8995). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the National Institutes of Health, or the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Kerry J. Stewart, Theodore DeWeese, Victoria Mock

Provision of study materials or patients: Jennifer A. Wenzel, Kathleen A. Griffith, JingJing Shang, Carol B. Thompson, Haley Hedlin, Kerry J. Stewart, Theodore DeWeese, Victoria Mock

Collection and/or assembly of data: Jennifer A. Wenzel, Kathleen A. Griffith, JingJing Shang, Carol B. Thompson, Haley Hedlin, Kerry J. Stewart, Theodore DeWeese, Victoria Mock

Data analysis and interpretation: Jennifer A. Wenzel, Kathleen A. Griffith, JingJing Shang, Carol B. Thompson, Haley Hedlin, Kerry J. Stewart, Theodore DeWeese, Victoria Mock

Manuscript writing: Jennifer A. Wenzel, Kathleen A. Griffith, JingJing Shang, Carol B. Thompson, Haley Hedlin, Kerry J. Stewart, Theodore DeWeese

Final approval of manuscript: Jennifer A. Wenzel, Kathleen A. Griffith, JingJing Shang, Carol B. Thompson, Haley Hedlin, Kerry J. Stewart, Theodore DeWeese, Victoria Mock

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section editors: Eduardo Bruera: None; Russell Portenoy: Pfizer, Grupo Ferrer, Xenon (C/A); Allergan, Boston Scientific, Covidien Mallinckrodt Inc., Endo Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Otsuka Pharma, ProStrakan, Purdue Pharma, Salix, St. Jude Medical (RF to institution)

Reviewer “A”: None

Reviewer “B”: None

Reviewer “C”: RTI-HS (E), (RF)

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board)

References

- 1.Mock V, Atkinson A, Barsevick A, et al. NCCN Practice Guidelines for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Oncology. 2000;14:151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blesch KS, Paice JA, Wickham R, et al. Correlates of fatigue in people with breast or lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean GE, Spears L, Ferrell BR, et al. Fatigue in patients with cancer receiving interferon alpha. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:164–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvine D, Vincent L, Graydon JE, et al. The prevalence and correlates of fatigue in patients receiving treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. A comparison with the fatigue experienced by healthy individuals. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17:367–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mock V, Burke MB, Sheehan P, et al. A nursing rehabilitation program for women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994;21:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: Results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ness KK, Wall MM, Oakes JM, et al. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: A population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweeney C, Schmitz KH, Lazovich D, et al. Functional limitations in elderly female cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:521–529. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorsen L, Dahl AA, Skovlund E, et al. Effectiveness after 1 year of a short-term physical activity intervention on cardiorespiratory fitness in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1301–1302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider CM, Hsieh CC, Sprod LK, et al. Effects of supervised exercise training on cardiopulmonary function and fatigue in breast cancer survivors during and after treatment. Cancer. 2007;110:918–925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4396–4404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mock V, Pickett M, Ropka ME, et al. Fatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise during cancer treatment. Cancer Pract. 2001;9:119–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009003119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock V, Dow KH, Meares CJ, et al. Effects of exercise on fatigue, physical functioning, and emotional distress during radiation therapy for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:991–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolden GG, Strauman TJ, Ward A, et al. A pilot study of group exercise training (GET) for women with primary breast cancer: Feasibility and health benefits. Psychooncology. 2002;11:447–456. doi: 10.1002/pon.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segal R, Evans W, Johnson D, et al. Structured exercise improves physical functioning in women with stages I and II breast cancer: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:657–665. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz AL. Daily fatigue patterns and effect of exercise in women with breast cancer. Cancer Pract. 2000;8:16–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.81003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz AL. Fatigue mediates the effects of exercise on quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:529–538. doi: 10.1023/a:1008978611274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne JK, Held J, Thorpe J, et al. Effect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older women with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:635–642. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.635-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adamsen L, Quist M, Andersen C, et al. Effect of a multimodal high intensity exercise intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3410. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winningham ML, MacVicar MG. The effect of aerobic exercise on patient reports of nausea. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1988;15:447–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacVicar MG, Winningham ML, Nickel JL. Effects of aerobic interval training on cancer patients' functional capacity. Nurs Res. 1989;38:348–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mock V, Frangakis C, Davidson NE, et al. Exercise manages fatigue during breast cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2005;14:464–477. doi: 10.1002/pon.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith K, Wenzel J, Shang J, et al. Impact of a walking intervention on cardiorespiratory fitness, self-reported physical function, and pain in patients undergoing treatment for solid tumors. Cancer. 2009;115:4874–4884. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mock V, Cameron LA, Tompkins C, et al. Every step counts: A walking exercise program for persons living with cancer. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities. Champagne, IL: Human Kinetics; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCorkle R, Quint-Benoliel J. Symptom distress, current concerns and mood disturbance after diagnosis of life-threatening disease. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:431–438. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmes S. Preliminary investigations of symptom distress in two cancer patient populations: Evaluation of a measurement instrument. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16:439–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb03434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang J, Wenzel J, Krumm S, et al. Who will drop out and who will drop in: Exercise adherence in a randomized clinical trial among patients receiving active cancer treatment. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:312–322. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318236a3b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, et al. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: Psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shacham S. A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J Pers Assess. 1983;47:305–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohl HW, Blair SN, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, et al. A mail survey of physical activity habits as related to measured physical fitness. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:1228–1239. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliveria SA, Kohl HW, III, Trichopoulos D, et al. The association between cardiorespiratory fitness and prostate cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199601000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welk GJ, Differding JA, Thompson RW, et al. The utility of the Digi-walker step counter to assess daily physical activity patterns. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S481–S488. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang JH, Chang HJ, Shim YH, et al. Effects of supervised exercise therapy in patients receiving radiotherapy for breast cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:443–450. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frangakis CE, Rubin DB. Principal stratification in causal inference. Biometrics. 2002;58:21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney HA, et al. A randomized trial of exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2003;12:347–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pickett M, Mock V, Ropka ME, et al. Adherence to moderate-intensity exercise during breast cancer therapy. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Fortmann SP, et al. Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample. Prev Med. 1986;15:331–341. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segar ML, Katch VL, Roth RS, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on self-esteem and depressive and anxiety symptoms among breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nieman DC, Cook VD, Henson DA, et al. Moderate exercise training and natural killer cell cytotoxic activity in breast cancer patients. Int J Sports Med. 1995;16:334–337. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz AL, Mori M, Gao R, et al. Exercise reduces daily fatigue in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:718–723. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200105000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters C, Lotzerich H, Niemeier B, et al. Influence of a moderate exercise training on natural killer cytotoxicity and personality traits in cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:1033–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters C, Lotzerich H, Niemeir B, et al. Exercise, cancer and the immune response of monocytes. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho MH, Dodd MJ, Cooper BA, et al. Comparisons of exercise dose and symptom severity between exercisers and nonexercisers in women during and after cancer treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:842–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical exercise and quality of life following cancer diagnosis: A literature review. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21:171–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02908298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinto BM, Trunzo JJ, Reiss P, et al. Exercise participation after diagnosis of breast cancer: trends and effects on mood and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2002;11:389–400. doi: 10.1002/pon.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]