Abstract

Theoretical models of social learning predict that animals should copy others in variable environments where resource availability is relatively unpredictable. Although short-term exposure to unpredictable conditions in adulthood has been shown to encourage social learning, virtually nothing is known concerning whether and how developmental conditions affect social information use. Unpredictable food availability increases levels of the stress hormone corticosterone (CORT). In birds, CORT can be transferred from the mother to her eggs, and have downstream behavioural effects. We tested how pre-natal CORT elevation through egg injection, and chick post-natal development in unpredictable food conditions, affected social information use in adult Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica). Pre-natal CORT exposure encouraged quail to copy the foraging decisions of demonstrators in video playbacks, whereas post-natal food unpredictability led individuals to avoid the demonstrated food source. An individual's exposure to stress and uncertainty during development can thus affect its use of social foraging information in adulthood. However, the stressor's nature and developmental timing determine whether an adult will tend to copy conspecifics or do the opposite. Developmental effects on social information use might thus help explain individual differences in social foraging tactics and leadership.

Keywords: developmental stress, environmental change, glucocorticoids, maternal programming, public information

1. Introduction

Animals can rely on their own, asocially acquired information, or that provided by others (‘social learning’) to make decisions. Depending on the pay-off, social learners may either copy or reject others' choices [1]. Theoretical models suggest that individuals should use social information only in specific circumstances for it to be adaptive [2], such as when foraging conditions are relatively unpredictable, and individuals are uncertain what to do [3]. One empirical study has supported these predictions: adult starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) briefly exposed to unpredictable food availability relied more on social information to make foraging decisions than did starlings in predictable environments, and obtained more food when they could access social information than when they could not [4]. However, it is not known how environmental predictability and its hormonal effects during an individual's development affect its later use of social foraging information.

Unpredictable food availability increases levels of the stress hormone corticosterone (CORT) [5]. In various avian species, experimentally elevated CORT levels in mothers cause CORT increases in their eggs [6]. The ‘environmental matching’ hypothesis poses that such maternal stress responses may ‘programme’ her offspring through the pre-natal environment for unpredictable or stressful conditions, enabling the development of traits beneficial in the offspring's future environment [6,7]. If so, then one might predict birds subjected to elevated pre-natal CORT, and to unpredictable food availability during post-natal development, to be more likely to copy others' foraging decisions than would individuals not developmentally ‘programmed’ to do so.

Alternatively, those individuals developing in stable, rich conditions might always outperform those subjected to stressful, unpredictable conditions in traits such as learning performance: the ‘silver spoon’ hypothesis [7]. Indeed, animals subjected to sufficiently high levels of stress during sensitive developmental periods suffer from cognitive impairments later in life [8]. Thus, according to the silver spoon hypothesis, developmentally stressed individuals should be of lower quality, and less capable of (social) learning than those with a stable development.

In this study, we tested how pre- and post-natal stress affected social information use in Japanese quail. We injected CORT into the egg yolks (pre-natal stress) and/or food-deprived the chicks on an unpredictable schedule (post-natal stress). We tested whether these quail as adults would feed from the same container as that chosen by video-recorded demonstrator quail. This study is the first to test a prominent but rarely addressed social learning theory in a developmental framework. As evidence for developmental conditions shaping adult phenotypes is accumulating [9], addressing this question might help explain consistent individual differences in social foraging tactics [10] and leadership [11].

2. Material and methods

(a). Model system

We studied Japanese quail, as quail mothers with elevated CORT lay eggs with increased CORT [12]. Furthermore, quail can imitate conspecifics to solve a novel foraging problem [13] and recognize conspecifics on video [14].

(b). Pre- and post-natal stress manipulations

We used 76 unrelated quail eggs. After 5 days of incubation, we manipulated pre-natal CORT exposure (n = 38) by injecting 10 µl CORT (850 ng ml−1) dissolved in sterile peanut oil at the egg apex, giving a dose of 8.5 ng CORT, which increases CORT yolk concentrations within 1.8 s.d. of those found in the breeding population (see the electronic supplementary material). We injected control eggs (n = 38) with peanut oil alone. Fifty-nine eggs hatched. One day post-hatching, we randomly allocated chicks of each pre-natal treatment to two pens with ad libitum food. When chicks were 4 days old, we assigned one pen of each pre-natal treatment (CORT or control) to one of two post-natal treatments: food removal for 25 per cent of daylight hours (3.5 h) on a random daily schedule for 15 days (Food-: n = 28), or ad libitum food at all times (Control: n = 31). After this time all birds were provided with ad libitum food until sexual maturity. We thus created four treatment groups: pre-natal control/post-natal control (n = 15, nine males, six females); pre-natal control/post-natal food- (n = 13, seven males, six females), pre-natal CORT/post-natal control (n = 16, four males, 12 females) and pre-natal CORT/post-natal food- (n = 15, nine males, six females). We conducted experiments in two batches (batch 1 = 31 chicks; batch 2 = 28 chicks).

(c). Social learning stimuli

To create demonstrator videos, we filmed one male and one female adult quail foraging together from one of two containers (one blue, the other pink) using a digital camera (Panasonic SD90) located at the height of the two containers (10 cm tall and 12 cm wide), only one of which was filled with dried mealworms. Container contents were not visible on the video. We merged clips of foraging quail into a 3 min 30 s video. For the social learning experiment, we played this file on an LED monitor (ViewSonic 24 inch, 1920 × 1080, 300 cd m−2) positioned 50 cm from the test subject's cage. We made two videos, one showing foraging from the pink container, and the other demonstrating the blue container. Demonstrated container colour was balanced within and across treatments.

(d). Social learning test

Adult quail (mean age 77.7 ± 5.1 days) were moved from their pens into individual cages (76 × 48 × 53 cm) and deprived of food for 2.5 h, after which the demonstrator video was played on a loop for 30 min. We then turned off the monitor and presented the test subject with two containers identical to, and in the same position as, those in the video. Both containers were baited with sawdust-covered mealworms so that subjects needed to peck in the containers to find food. We filmed subjects' reactions to the containers for 10 min. From these videos, we scored the first container each test subject approached within pecking distance (less than 5 cm), and the first container it pecked in.

(e). Statistical analyses

We used generalized linear models (GLMs) to examine how pre-natal and post-natal treatments affected the proportion of test subjects that first approached and pecked in the demonstrated container using the GENMOD procedure with binomial law in SAS v. 9.2 (SAS Institute Corporation). We included pre- and post-natal treatments, sex, batch and all their interactions in each model, and sequentially dropped terms with p > 0.10, until the minimal model contained only significant terms. We considered p < 0.05 as significant. We report the results of these minimal models in the main text, but the full models and those containing all manipulated fixed effects as well as batch and sex can be found in the electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S6. We used two-tailed binomial tests to assess whether proportions were significantly different from chance.

3. Results

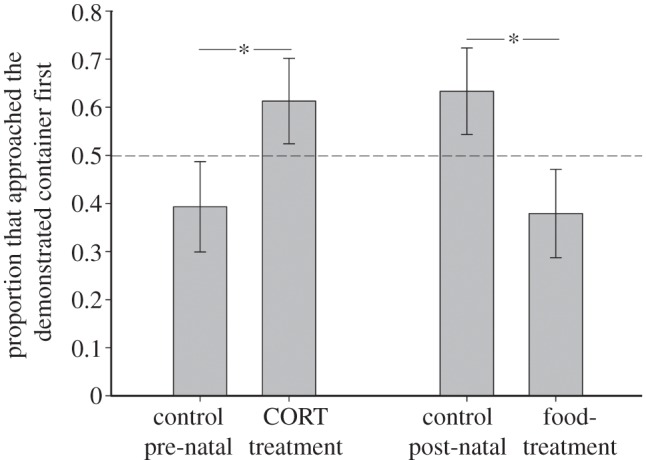

There were no significant interactions between pre- and post-natal treatments, sex and batch predicting the dependent variables (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2). Both pre- and post-natal treatments affected the proportion of individuals approaching the demonstrated container first, but in opposite directions: a larger proportion of CORT than control quail approached the demonstrated container first (GLM:  p = 0.02; figure 1). In contrast, fewer food- than control quail approached the demonstrated container first (GLM:

p = 0.02; figure 1). In contrast, fewer food- than control quail approached the demonstrated container first (GLM:  p = 0.008; figure 1). None of these proportions differed from chance (binomial tests: z < 1.62, p > 0.15). More male than female quail approached the demonstrated container first (GLM:

p = 0.008; figure 1). None of these proportions differed from chance (binomial tests: z < 1.62, p > 0.15). More male than female quail approached the demonstrated container first (GLM:  p = 0.02).

p = 0.02).

Figure 1.

Proportion of adult quail from each pre- and post-natal treatment group that approached the demonstrated container first. Bars show means ± s.e., the asterisks indicate significant differences and the dotted line indicates random choice.

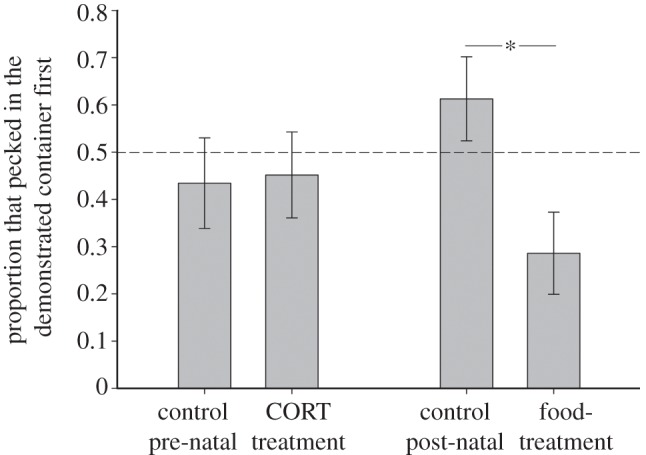

The proportion of test subjects that pecked in the demonstrated container first was not influenced by pre-natal treatment (GLM:  p = 0.16; figure 2) nor sex (GLM:

p = 0.16; figure 2) nor sex (GLM:  p = 0.35). However, a smaller proportion of food- quail, when compared with controls, pecked in the demonstrated container first (GLM:

p = 0.35). However, a smaller proportion of food- quail, when compared with controls, pecked in the demonstrated container first (GLM:  p = 0.007; figure 2), and only this proportion differed significantly from chance (binomial tests: Food-: z = 2.27, p = 0.04; other groups: z < 1.26, p > 0.28). Batch was a significant predictor of the proportion of quail that pecked in the demonstrated container first (GLM:

p = 0.007; figure 2), and only this proportion differed significantly from chance (binomial tests: Food-: z = 2.27, p = 0.04; other groups: z < 1.26, p > 0.28). Batch was a significant predictor of the proportion of quail that pecked in the demonstrated container first (GLM:  p = 0.003). However, there were no significant interactions between batch and pre- or post-natal treatment effects. Although the statistical differences between treatment groups as described above are less likely to be detected in each batch separately owing to the reduced sample size (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S3–S6), figures S1 and S2 in the electronic supplementary material show very similar patterns with regard to differences between treatment groups in both batches.

p = 0.003). However, there were no significant interactions between batch and pre- or post-natal treatment effects. Although the statistical differences between treatment groups as described above are less likely to be detected in each batch separately owing to the reduced sample size (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S3–S6), figures S1 and S2 in the electronic supplementary material show very similar patterns with regard to differences between treatment groups in both batches.

Figure 2.

Proportion of adult quail from each pre- and post-natal treatment group that pecked in the demonstrated container first. Bars show means ± s.e., the asterisk indicates a significant difference and the dotted line indicates random choice.

4. Discussion

Our study shows that both pre- and post-natal stress affected quails' use of social foraging information, but in opposite directions. Individuals with pre-natally increased CORT levels were more likely than controls to approach the demonstrated food source. By contrast, individuals post-natally subjected to unpredictable food availability were more likely than controls to both approach and peck first in the container that was avoided by the videoed demonstrators. Control quail tended to show foraging decisions in the opposite direction to the quail in the treatment groups, but their food container choices did not differ significantly from chance. These results do not fit the environmental matching hypothesis, which predicted that CORT/food- quail would copy demonstrators most, nor the silver spoon hypothesis, which predicted that control/control quail would use social information most. Instead, they suggest that both the nature and developmental timing of a stressor determine its effects on social learning in adulthood, and that unstressed subjects in some circumstances might not use social information when not developmentally primed to do so. Whether these behaviours are adaptive requires further testing in a natural environment where the survival and reproductive success of quail with different developmental trajectories can be measured.

This is the first study to suggest that pre-natal CORT elevations may encourage social information use regardless of post-natal treatment, but the consistency and strength of this effect across behavioural contexts require further investigation using larger sample sizes. Similarly, more research is required to address whether there are consistent sex differences in quail social information use. We observed qualitatively very similar differences between treatment groups in each of the two batches of quail tested. However, quail in batch 2 seemed generally less inclined to peck in the demonstrated container than quail in batch 1, which might explain why ‘batch’ was a significant predictor of the proportion of quail that pecked in the demonstrated container first. Whether this difference between batches is a biologically interesting consequence of undetected differences in the specific social environment in which quail in each batch developed, or whether it is a side-effect of random genetic differences and/or limited sample size requires further investigation.

Quail post-natally exposed to unpredictable food availability significantly preferred the non-demonstrated container. This behaviour might be explained by these birds having learned during the treatment period to feed from sources that were not exploited/depleted by others already. Food- quail developed in an environment where food was depleted at unpredictable times, and when we returned the feeder they competed over access as they could not all feed simultaneously. Other studies suggest that animals' use of social foraging information is influenced by their experience of conspecifics depleting resources. For example, grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) rewarded for copying the container choice of a demonstrator learned more slowly than squirrels rewarded for making the opposite choice. As squirrels naturally store food in individual caches, they would have learned to associate the sight of a conspecific removing food from a location with absence of food in that location [15]. Similarly, starlings were more likely to learn a symbol-reward association from seeing demonstrators pick the unrewarded rather than the rewarded symbol [16]. Templeton [16] argued that observing a conspecific's foraging success can be ambiguous: it might indicate either that the demonstrated location is a rich food source worthy of further exploitation, or that it is being depleted. How to interpret such public information is likely to depend on an individual's previous experience of competition. Unpredictable food availability during development might thus encourage individuals to socially learn what not to do to avoid competition in adulthood. This ‘resource-depletion’ hypothesis would be interesting to test in future studies.

Our study is the first to show that developmental stressors affect adult social information use and that these effects depend on the stressor's nature and timing. As natural conditions present a wide range of different stressors at various developmental stages, these factors may help explain why certain social foragers choose to scrounge from others' findings [10], and why specific individuals tend to lead groups while others follow [11].

Acknowledgements

Experimental procedures were carried out under Home Office Animals (Scientific) Procedures Act project licence 60/4068 and personal licence 70/1364.

This study was funded by a Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research Rubicon Grant to N.J.B., and a BBSRC David Phillips Research Fellowship to K.A.S. We thank the animal care staff for bird care, and Jeremy Schwartzentruber and Alex Thornton for comments.

References

- 1.Seppänen J-T, Forsman JT, Mönkkönen M, Krams I, Salmi T. 2011. New behavioural trait adopted or rejected by observing heterospecific tutor fitness. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1736–1741 10.1098/rspb.2010.1610 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1610) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laland KN. 2004. Social learning strategies. Learn. Behav. 32, 4–14 10.3758/BF03196002 (doi:10.3758/BF03196002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. 1988. An evolutionary model of social learning: the effects of spatial and temporal variation. In Social learning: a psychological and biological approach (eds Zentall TR, Galef BG.), pp. 29–48 Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafacz M, Templeton JJ. 2003. Environmental unpredictability and the value of social information for foraging starlings. Ethology 109, 951–960 10.1046/j.0179-1613.2003.00935.x (doi:10.1046/j.0179-1613.2003.00935.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan KL, Spencer KA, Goldsmith AR, Catchpole CK. 2003. Song as an honest signal of past developmental stress in the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 1149–1156 10.1098/rspb.2003.2330 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2330) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriksen R, Rettenbacher S, Groothuis TGG. 2011. Prenatal stress in birds: pathways, effects, function and perspectives. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 1484–1501 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.010 (doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monaghan P. 2008. Early growth conditions, phenotypic development and environmental change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 1635–1645 10.1098/rstb.2007.0011 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.0011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. 2009. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 434–445 10.1038/nrn2639 (doi:10.1038/nrn2639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer KA, Verhulst S. 2007. Delayed behavioral effects of postnatal exposure to corticosterone in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). Horm. Behav. 51, 273–280 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.11.001 (doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.11.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morand-Ferron J, Varennes E, Giraldeau L-A. 2011. Individual differences in plasticity and sampling when playing behavioural games. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1223–1230 10.1098/rspb.2010.1769 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1769) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harcourt JL, Ang TZ, Sweetman G, Johnstone RA, Manica A. 2009. Social feedback and the emergence of leaders and followers. Curr. Biol. 19, 248–252 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.051 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayward LS, Wingfield JC. 2004. Maternal corticosterone is transferred to avian yolk and may alter offspring growth and adult phenotype. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 135, 365–371 10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.11.002 (doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.11.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akins CK, Klein ED, Zentall TR. 2002. Imitative learning in Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) using the bidirectional control procedure. Anim. Learn. Behav. 30, 275–281 10.3758/BF03192836 (doi:10.3758/BF03192836) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ophir AG, Galef BG. 2003. Female Japanese quail affiliate with live males that they have seen mate on video. Anim. Behav. 66, 369–375 10.1006/anbe.2003.2229 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2229) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopewell LJ, Leaver LA, Lea SEG, Wills AJ. 2009. Grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) show a feature-negative effect specific to social learning. Anim. Cogn. 13, 219–227 10.1007/s10071-009-0259-3 (doi:10.1007/s10071-009-0259-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Templeton JJ. 1998. Learning from others’ mistakes: a paradox revisited. Anim. Behav. 55, 79–85 10.1006/anbe.1997.0587 (doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0587) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]