Abstract

Background

Because of the role of inflammation in preterm birth (PTB), polymorphisms in and near the interleukin-6 gene (IL6) have been association study targets. Several previous studies have assessed the association between PTB and a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs1800795, located in the IL6 gene promoter region. Their results have been inconsistent and SNP frequencies have varied strikingly among different populations. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis with subgroup analysis by population strata to: (1) reduce the confounding effect of population structure, (2) increase sample size and statistical power, and (3) elucidate the association between rs1800975 and PTB.

Results

We reviewed all published papers for PTB phenotype and SNP rs1800795 genotype. Maternal genotype and fetal genotype were analyzed separately and the analyses were stratified by population. The PTB phenotype was defined as gestational age (GA) < 37 weeks, but results from earlier GA were selected when available. All studies were compared by genotype (CC versus CG+GG), based on functional studies.

For the maternal genotype analysis, 1,165 PTBs and 3,830 term controls were evaluated. Populations were stratified into women of European descent (for whom the most data were available) and women of heterogeneous origin or admixed populations. All ancestry was self-reported. Women of European descent had a summary odds ratio (OR) of 0.68, (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 – 0.91), indicating that the CC genotype is protective against PTB. The result for non-European women was not statistically significant (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.59 - 1.75). For the fetal genotype analysis, four studies were included; there was no significant association with PTB (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.72 - 1.33). Sensitivity analysis showed that preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM) may be a confounding factor contributing to phenotype heterogeneity.

Conclusions

IL6 SNP rs1800795 genotype CC is protective against PTB in women of European descent. It is not significant in other heterogeneous or admixed populations, or in fetal genotype analysis.

Population structure is an important confounding factor that should be controlled for in studies of PTB.

Keywords: Preterm birth, Preterm delivery, Premature birth, Premature delivery, Genetic polymorphism, Genetic variant, Single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP, Interleukin-6, Cytokine, Population structure, HapMap project, Phenotype heterogeneity

Background

Preterm birth (PTB) is defined as birth before 37 completed weeks’ gestation. Prematurity is the leading cause of neonatal mortality in newborns without congenital anomalies or chromosomal abnormalities [1,2]. It is also associated with a broad spectrum of lifelong morbidity in survivors, including neurodevelopmental delay, cerebral palsy, blindness, deafness, and chronic lung disease [3,4]. Despite efforts to reduce preterm birth, the rate has remained relatively stable over the last few decades and was 11.7% in the United States in 2011 [1,5]. Although PTB is a pressing public health issue, the incomplete understanding of genetic and environmental risk factors has inhibited development of effective prevention and treatment strategies.

The etiology of PTB is complex and multifactorial [6-9]. There is compelling evidence that both maternal and fetal genomes contribute to risk [10-12], and PTB prevalence varies among population groups [13-17]. African-American ancestry is consistently associated with an increased risk of preterm birth even after adjusting for epidemiologic risk factors, such as income, education, lack of prenatal care, and other socioeconomic factors [6,18,19]. The heritability of PTB, based on twin studies, is estimated to be approximately 30% [20-22].

Despite strong evidence of a genetic component, consistent identification of risk loci has been challenging. A promising candidate gene has been interleukin-6 (IL6). This gene encodes the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is involved in the regulation of innate immunity. Several studies have shown that PTB is associated with increased concentration of IL-6 in maternal serum, cervicovaginal secretions and amniotic fluid [23-25]. Many IL6 polymorphisms have been assessed for association with preterm birth [26]. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs1800795, usually referred to as IL6 -174 (from the transcription start site) or -237 (from the translation start site), is located within the IL6 promoter region [27,28] and is one of the most thoroughly studied IL6 variants. This SNP is located in the segment of the IL6 promoter that is crucial for transcriptional induction with viruses and other cytokines [27,28]. Expression studies of IL-6 with allelic variants of the rs1800795 polymorphism have produced different results in different tissues [29-31]. Nevertheless, studies using HeLa cell lines showed that the derived C-allele is associated with a significantly lower level of IL6 expression (0.624-fold lower) [32]. In addition, adults with the CC genotype have significant lower plasma concentrations of IL-6, compared with adults with the GG or GC genotypes (1.63 pg/mL v.s. 2.74 or 2.64 pg/mL) [32].

Studies of the association between the IL6 rs1800795 polymorphism and PTB have yielded inconsistent results. Simhan et al. (2003) reported that the CC genotype is protective for PTB compared to the CG and GG genotypes [33]. However, others [34-44] have shown no significant association between IL6 and PTB. Hapmap data show that the C allele has a frequency of 0.53 in the CEU population (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe), but it is absent in the YRI (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria), CHB (Han Chinese in Beijing, China) and JPT (Japanese in Tokyo, Japan) populations [45]. Because previous studies have been limited by small sample size and by potential population stratification, we hypothesized that the inconsistent results for rs1800795 are, at least in part, explained by differences in population structure and admixture. Here, we carry out a meta-analysis to systematically review the association of rs1800795 with spontaneous PTB, and to specifically explore the SNP association within population strata.

Results

Included studies

Thirty-three articles were identified from the initial keywords search. After review, 21 were excluded (see Additional file 1). Table 1a and 1b summarize the characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis, including study populations, whether or not preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM) was excluded, cutoff for the cases and controls, and sample sizes (Table 1a and 1b). For maternal genotype analysis, a total of ten studies were included. This resulted in 1,165 PTB cases and 3,830 term controls, more than tripling the case sample size of any individual study (Table 1a). For the fetal analysis, only four studies could be included, with 785 PTB cases and 882 term controls (Table 1b).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

|

(a). Characteristics of the studies included for maternal genotype analysis | ||||||||

|

Author |

Year |

Country |

Populations |

PPROM Excluded? |

PTB cases group criteria |

Case sample size |

Control group criteria |

Control sample size |

|

Women of European descent | ||||||||

| Annells et al |

2004 |

Australia |

White |

No |

GA<35 |

202 |

GA≥37 |

185 |

| Hartel et al |

2004 |

Germany |

White |

No |

GA<37 and VLBW |

365 |

GA≥37 |

281 |

| Hollegaard et al |

2008 |

Denmark |

White |

No |

GA<37 |

62 |

GA≥37 |

55 |

| Menon et al |

2005 |

TN & PA, USA |

White |

No |

GA<36 |

101 |

GA≥37 |

326 |

| Simhan et al |

2003 |

PA. USA |

White |

Yes |

GA<34 |

39 |

GA≥37 |

110 |

| Stonek et al |

2008 |

Austria |

White |

No |

GA<34 |

21 |

GA≥37 |

1367 |

|

Heterogeneous population | ||||||||

| Gomez et al |

2010 |

PA, USA |

African American, and others |

No |

GA<37 |

60 |

GA≥37 |

636 |

| Harper et al |

2011 |

USA |

White, African American, Asian, and Others |

No |

GA<28 |

33 |

GA≥37 |

549 |

| Moura et al |

2009 |

Brazil |

Mulatto |

No |

GA<37 |

111 |

GA≥37 |

94 |

| Moura et al |

2009 |

Brazil |

Mulatto and White |

No |

GA<37 |

80 |

GA≥37 |

101 |

| Simhan et al |

2003 |

PA. USA |

African American |

Yes |

GA<34 |

12 |

GA≥37 |

46 |

| Speer et al |

2006 |

IL, USA |

White, African American, and Others |

No |

GA<35 |

79 |

GA≥37 |

80 |

|

(b). Characteristics of the studies included for fetal genotype analysis | ||||||||

|

Women of European descent | ||||||||

| Hartel et al |

2004 |

Germany |

White |

No |

GA<37 and VLBW |

606 |

GA≥37 |

491 |

|

Heterogeneous population | ||||||||

| Pereyra et al |

2012 |

Uruguay |

Uruguayan |

No |

GA<37 |

53 |

GA≥37 |

56 |

| Speer et al |

2006 |

IL, USA |

White, African American, and Others |

No |

GA<35 |

78 |

GA≥37 |

78 |

| Velez et al | 2007 | TN & PA, USA | African American | Yes | GA<36 | 48 | GA≥37 | 257 |

Each study was stratified by population into (1) European ancestry or (2) heterogeneous population – either the studied samples were from admixed populations or contained several different populations and could not be stratified based on available information. All ancestry was self-reported. None of the studies used ancestry-informative markers to determine the ancestry of the samples.

Among all the included studies, only one in the maternal group [33] and one in the fetal group [44] excluded PPROM (Table 1a and 1b). Several studies had a gestational age (GA) cut-offs earlier than 37 weeks: Harper et al. [36] at 28 weeks, Simhan et al. [33] and Stonek et al. [43] at 34 weeks. Hartel et al. [37] used a GA cut-off of 37 weeks and very low birth weight as the PTB case criteria, thereby selecting a more severe phenotype.

Association of genotype and phenotype

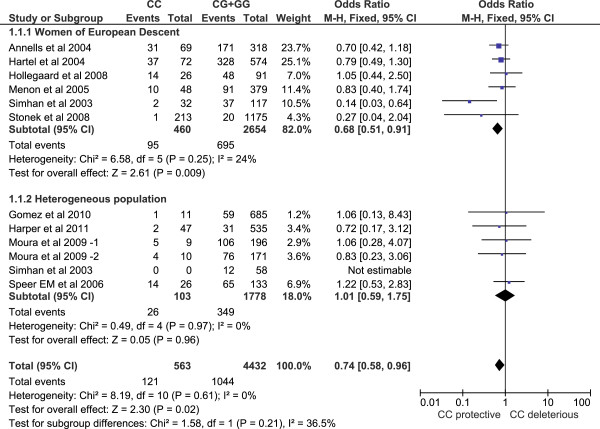

Both Cochrane's Q test and the I-square statistic suggest that there is no evidence of heterogeneity across all studies or for each subgroup (Figures 1 and 2), for maternal or fetal genotype analysis. Thus, a Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effect model [46] was employed to pool all studies for summary OR estimation.

Figure 1.

Forest plot for maternal genotype analysis. The count for genotypes, weight, OR, 95% confidence interval for each study; summary for each subgroup population; and heterogeneity test statistics are shown. Each square represents an OR for each specific study, and the area is proportional to the weight. Each horizontal line shows the 95% CI for each study. The diamonds are the summary OR for each subgroup population or for the total. The CC genotype is significantly protective against PTB in women of European descent (OR=0.68, 95% CI 0.51 – 0.91). It is not significant in heterogeneous populations.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for fetal genotype analysis. The count for genotypes, weight, odds ratio, 95% confidence interval for each study; summary for each subgroup population; and heterogeneity test statistics are shown. Each square represents the odds ratio for each specific study, and the area is proportional to the weight. Each horizontal line shows the 95% confidence interval for each study. The diamonds are the summary odds ratio for each subgroup population or for the total. The association between rs1800795 and PTB is not significant for fetuses of European descent, or for those of heterogeneous populations.

For the maternal genotype analysis, the overall OR is 0.74 for genotype CC versus CG+GG (95% CI 0.58 – 0.96), demonstrating a significant protective effect of the CC genotype. In subgroup analysis, women of European descent have an OR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.51 - 0.91), but the association is not significant in other populations (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.59 – 1.75) (Figure 1 Forest plot).

For the fetal genotype analysis, the overall OR for genotype CC versus CG+GG is 0.98 (95% CI 0.72 – 1.33). Although genotype CC showed a trend toward a protective effect in infants of European descent, the result is not significant (Figure 2 Forest plot).

Bias assessment

For maternal genotype sensitivity analysis, the overall OR after exclusion of any individual study showed no change of the trend - ranging from 0.71 to 0.81 - indicating a robust protective effect of the CC genotype against PTB. In the European descent subgroup, the sensitivity analysis was still stable, with summary ORs ranging from 0.63 to 0.76. However, exclusion of one study [33] produced a summary OR with borderline significance (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.57 – 1.03) (Table 2a). Interestingly, this was the only maternal study that excluded PPROM (Table 1a). This result suggests that PPROM may thus be a confounding factor and deserves separate analysis to reduce phenotypic heterogeneity. Unfortunately, we had insufficient data to stratify by the presence or absence of PPROM. Fetal genotype sensitivity analysis also showed no change in the trend (Table 2b).

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis

|

(a). Maternal genotype sensitivity analysis | ||

|

Study omitted |

Overall OR |

Subgroup OR |

|

Women of European descent | ||

| Annells et al 2004 |

0.76 [0.57, 1.01] |

0.68 [0.48, 0.95] |

| Hartel et al 2004 |

0.73 [0.54, 0.98] |

0.63 [0.45, 0.90] |

| Hollegaard et al 2008 |

0.72 [0.55, 0.94] |

0.65 [0.48, 0.88] |

| Menon et al 2005 |

0.73 [0.56, 0.96] |

0.66 [0.48, 0.90] |

| Simhan et al 2003 |

0.81 [0.63, 1.05] |

0.76 [0.57, 1.03] |

| Stonek et al 2008 |

0.76 [0.59, 0.99] |

0.71 [0.53, 0.94] |

|

Heterogeneous population | ||

| Gomez et al 2010 |

0.74 [0.57, 0.95] |

1.01 [0.57, 1.78] |

| Harper et al 2011 |

0.74 [0.57, 0.96] |

1.08 [0.60, 1.96] |

| Moura et al 2009 -1 |

0.73 [0.57, 0.95] |

1.00 [0.55, 1.83] |

| Moura et al 2009 -2 |

0.74 [0.57, 0.96] |

1.06 [0.58, 1.93] |

| Simhan et al 2003 |

n/a |

n/a |

| Speer EM et al 2006 |

0.71 [0.54, 0.92] |

0.88 [0.43, 1.83] |

|

(b). Fetal genotype sensitivity analysis | ||

|

Study omitted |

Overall OR |

Subgroup OR |

|

Women of European descent | ||

| Hartel et al 2004 |

1.45 [0.63, 3.35] |

n/a |

|

Heterogeneous population | ||

| Pereyra et al 2012 |

n/a |

n/a |

| Speer et al 2006 |

0.92 [0.66, 1.28] |

1.07 [0.12, 9.39] |

| Velez et al 2007 | 0.97 [0.71, 1.33] | 1.53 [0.61, 3.83] |

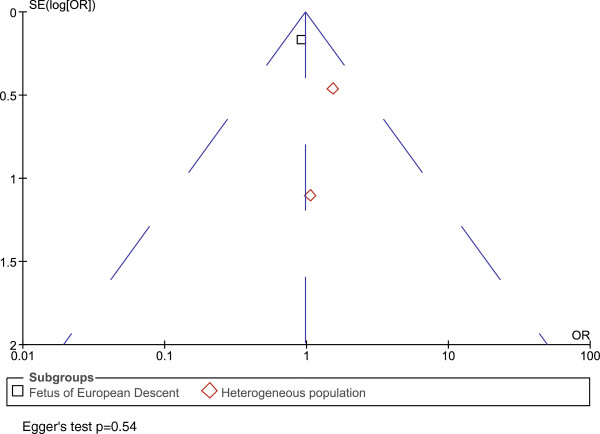

Funnel plots were symmetrical for both the maternal and fetal analyses, indicating no publication bias. Egger's test [47] also showed no evidence of publication bias (p=0.43 for maternal genotype analysis, p=0.54 for infant genotypes) (Figures 3 and 4 Funnel plots).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for maternal genotype analysis. Funnel plot was showing OR versus standard error (SE). Egger’s test p value is also shown. Each square or diamond represents a study. Squares and diamonds represent different subgroup populations. There is no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for fetal genotype analysis. Funnel plot showing OR versus standard error (SE). Egger’s test p value is also shown. Each square or diamond represents a study. Squares and diamonds represent different subgroup populations. There is no evidence of publication bias.

Discussion

Population heterogeneity may help to explain why results among genetic studies of rs1800795 and PTB association were inconsistent. Indeed, HapMap data showed that the frequency of the derived C allele of rs1800795 is 0 in the YRI, CHB, and JPT populations, while it is 0.53 in the CEU population [45]. In other population samples, the C allele frequency is consistently high in people of European descent, ranging from 0.35 in Tuscans from Italy to 0.65 in a European-American sample ascertained for coronary artery disease. In contrast, the C allele frequency is consistently low in East Asian (highest in Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado, 0.006) and African (highest in Maasai in Kinyawa, 0.049) populations. The frequency in admixed populations varies. The Programs for Genomic Applications' African-American panel reported a frequency of 0, a population with African ancestry in Southwest USA had a frequency of 0.092, while a population with Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles had a frequency of 0.16 [48]. The allele frequency difference of 0.53 between people of European descent and populations in other continents falls within the 5% tail of continental allele frequency differences for a large panel of common SNPs (see Additional file 2) and is thus statistically significant. This variation suggests that population heterogeneity could have strong effects for this polymorphism. After stratification by population, our subgroup analysis showed that the rs1800795 CC genotype is significantly protective against PTB in women of European descent, but not in other heterogeneous populations (Figure 1). In the latter group of populations, ancestral diversity is likely to obscure any potential genotype-phenotype association, emphasizing the importance of addressing underlying population structure in genetic studies.

A regression analysis reveals a negative relationship between OR and CC genotype frequency (see Additional file 3). The result is significant in maternal studies. This matches the finding that in European populations, which have high CC genotype frequencies, the CC genotype has a protective effect against PTB; while in ethnically heterogeneous populations, which have low or zero CC genotype frequencies, no protective effect could be observed.

In all these studies, all ancestry was self-reported. Unfortunately, genetic admixture data confirming self-reported ancestry are not available. However, previous studies have demonstrated nearly 100% concordance between self-reported race/ethnicity and specific genetic ancestry markers among pregnant women enrolled in clinical studies [18]. Although we cannot exclude the possibility of misclassification of some women, we infer a similar high rate of concordance between self-reported race/ethnicity and genotyped race/ethnicity among women enrolled in this meta-analysis.

It is intriguing that rs1800795 has such large frequency differences across different populations. In addition to its association with PTB, this SNP has been shown to be associated with many other diseases, such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [32], susceptibility to Kaposi sarcoma [49], metabolic syndrome [50-54], and inflammatory bowel disease [55]. However, there is no strong evidence of natural selection near rs1800795 [56-58].

Methodological differences may have contributed to the inconsistent results among prior studies. Most studies compared CC vs. CG+GG, but some reported GG vs. CG+CC and others compared individual alleles rather than genotypes. Because of the evidence that CC genotypes cause significantly lower serum IL-6 concentrations than do the CG or GG genotypes [32], we uniformly meta-analyzed CC versus CG+GG for all studies, providing a consistent approach to the genotype-phenotype correlation.

Another goal of our meta-analysis was to increase statistical power by increasing the sample size. For women of European descent, we pooled 790 PTB cases and 2,324 controls, which significantly increased the sample size relative to any previous individual study. With this sample size, we have 97.72% power to detect an OR of 0.68 at the 0.05 significance level. Under the same conditions, the single study with the largest case sample size [37] had only 51.38% power.

The purpose of this meta-analysis is to pool peer-reviewed published studies that qualify our inclusion criteria (see Additional file 1). Even though there is no evidence of publication bias (Figures 3 and 4), a potential limitation of our study is that some findings of no association between rs1800795 and PTB may not have been reported in the literature and therefore could not be included in our meta-analysis.

In addition to population structure, phenotypic heterogeneity is another problem that may undermine studies of any complex diseases. In this meta-analysis, we stratified by population, included the data from earlier GA cutoffs, and selected earlier PTB cases. Therefore, our conclusion that the CC genotype of rs1800795 in the IL6 promoter is protective against PTB is limited to European women with early PTB. Our sensitivity test showed that PPROM may be a confounding factor. Besides early PTB and PPROM, further refinement of PTB phenotype, such as a sub-classification by placenta abruption, cervical insufficiency, and other factors, may also help to reduce phenotype heterogeneity.

Conclusions

In summary, we performed a meta-analysis of the association between PTB and a polymorphism located in the IL6 promoter region, SNP rs1800795. We specifically stratified the analysis by population subgroup and selected for early PTB. We found the derived CC genotype is protective against PTB in women of European ancestry. No significant associations were found for non-European samples, in whom the CC genotype frequency is low. PPROM may be a confounding factor contributing to phenotype heterogeneity and deserves further investigation.

Methods

Data sources

A literature search was conducted in PubMed (U.S. national Library of Medicine, Jan 1966-April 2012) to identify studies of the association between IL6 rs1800795 and PTB. Keywords included: (“interleukin 6 polymorphism”, or “interleukin 6 variant”, or “interleukin 6 genotype”), AND (“preterm birth” OR “preterm delivery”). The “AND” operator was used to combine these terms in varying combinations. No search software was used. After these studies were retrieved, they were individually reviewed. Bibliographies of all articles retrieved were further reviewed for potentially eligible studies (see Additional file 1).

Study selection and data extraction

We included human studies with: (1) a genotype of IL6 SNP rs1800795 (also referred as IL6 -174 or -237) and (2) a collection of affected PTB cases and unaffected controls. Two authors (W.W. and E.A.S.C) independently searched and reviewed the articles. If studies only presented summary data, we contacted the authors for genotype counts and population stratification as needed (see Additional file 1). Publications were excluded if the rs1800795 genotype distribution for cases and controls could not be determined, or if the control group was reported to deviate significantly from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Non-English language papers were also excluded. When two or more articles were published by the same group of authors, we evaluated the studies for evidence of overlapping samples. If the paper, or author correspondence, suggested overlapping cohorts, we included only the first study for meta-analysis. The study population geographic origins, criteria for PTB diagnosis, occurrence of PPROM, sample source (maternal or fetal), and genotype count for affected and unaffected individuals were extracted.

Selection of outcomes

All studies of PTB with GA <37 weeks were eligible for inclusion. If multiple GA cut-offs <37 weeks were reported, we selected the cut-off that was one level earlier than 37 weeks in order to ensure an accurate phenotype and to reduce phenotype heterogeneity. This approach allows us to reduce classification error for PTB occurring near GA=37 weeks, and tends to select for a more severe phenotype (earlier PTB), further helping to reduce phenotype heterogeneity.

PPROM is a distinct subset of PTB and is frequently excluded in PTB studies [26]. Exclusion of PPROM would further reduce phenotype heterogeneity; however, among all IL6-PTB association studies, only two excluded PPROM [33,44] (Table 1a and 1b). Therefore, study selection was not predicated on exclusion of PPROM.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis compared the CC versus CG+GG genotypes, based on prior functional studies that suggest a similar phenotype for the latter two genotypes [32]. Maternal and fetal genotypes were analyzed separately. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochrane’s Q test of heterogeneity and the I-square statistic [59,60]. If there was no significant heterogeneity, a Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effect model [46] was employed to calculate the pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Otherwise, the random-effects model was used. Subgroup analysis was performed to test for the effects of population stratification. Sensitivity analysis was performed by omitting one publication at a time. Funnel plots and Egger's test [47] were used to assess publication bias. The analysis was carried out using RevMan 5.0 [61], and STATA 11 [62]. This article was prepared based on the guideline of “meta-analyses of observational studies” (MOOSE) [63]. A MOOSE checklist is shown in Additional file 4 (see Additional file 4).

Abbreviations

IL6: Interleukin-6 (gene); IL-6: Interleukin-6 (protein); PTB: Preterm birth; GA: Gestational age; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; PPROM: Preterm premature rupture of membrane; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium; MOOSE: Meta-analyses of observational studies.

Competing interests

None of the authors reports any competing interests relative to the work presented in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

WW conceived of and designed the study. EASC, GS, WSW, MSE, TAM, JX, MV, and LBJ provided input to the study design. WW, EASC, GS, and WSW conducted the analysis. WW and EASC drafted the manuscript. GS, WSW, MSE, TAM, JX, MV, and LJ provided critical review of the manuscript. MV and LBJ oversaw the analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

All the included and excluded papers and the reasons of inclusion or exclusion.

Distribution of SNPs allele frequency differences for three continental populations.

Meta-regression analysis for (a) maternal genotype studies, (b) fetal genotype studies.

MOOSE checklist.

Contributor Information

Wilfred Wu, Email: wilfred.wu@utah.edu.

Erin A S Clark, Email: erin.clark@hsc.utah.edu.

Gregory J Stoddard, Email: greg.stoddard@hsc.utah.edu.

W Scott Watkins, Email: swatkins@genetics.utah.edu.

M Sean Esplin, Email: sean.esplin@imail.org.

Tracy A Manuck, Email: tracy.manuck@hsc.utah.edu.

Jinchuan Xing, Email: Xing@dls.rutgers.edu.

Michael W Varner, Email: michael.varner@hsc.utah.edu.

Lynn B Jorde, Email: lbj@genetics.utah.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Margaret Harper, Mads Hollegaard, Scott M. Williams, Digna R Velez Edwards, Stephanie Engel, and William Patrick Duff, for the correspondences about their works and publications on rs1800795 and PTB. This investigation was supported by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764). EASC is supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD061910). JX is supported by National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute (R00HG005846).

References

- Hamilton BE, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics. 2013;131:548–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew T, MacDorman M. Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2003 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2006;54:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood NS, Marlow N, Costeloe K, Gibson AT, Wilkinson AR. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. EPICure Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:378–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damus K. Prevention of preterm birth: a renewed national priority. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:590–596. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283186964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju TNK. Epidemiology of late preterm (near-term) births. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:751–763. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.09.009. abstract vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistka ZA-F, Palomar L, Lee KA, Boslaugh SE, Wangler MF, Cole FS, DeBaun MR, Muglia LJ. Racial disparity in the frequency of recurrence of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:131. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.093. e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW Jr, David RJ, Handler A, Wall S, Andes S. Very low birthweight in African American infants: the role of maternal exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2132–2138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:529–535. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R, Lie RT. Familial patterns of preterm delivery: maternal and fetal contributions. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:474–479. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett J, Feitosa MF, Trusgnich M, Wangler MF, Palomar L, Kistka ZA-F, DeFranco EA, Shen TT, Stormo AED, Puttonen H, Hallman M, Haataja R, Luukkonen A, Fellman V, Peltonen L, Palotie A, Daw EW, An P, Teramo K, Borecki I, Muglia LJ. Mother’s genome or maternally-inherited genes acting in the fetus influence gestational age in familial preterm birth. Hum Hered. 2009;68:209–219. doi: 10.1159/000224641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haataja R, Karjalainen MK, Luukkonen A, Teramo K, Puttonen H, Ojaniemi M, Varilo T, Chaudhari BP, Plunkett J, Murray JC, McCarroll SA, Peltonen L, Muglia LJ, Palotie A, Hallman M. Mapping a new spontaneous preterm birth susceptibility gene, IGF1R, using linkage, haplotype sharing, and association analysis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esplin MS, O’Brien E, Fraser A, Kerber RA, Clark E, Simonsen SE, Holmgren C, Mineau GP, Varner MW. Estimating recurrence of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:516–523. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184181a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MM, Elam-Evans LD, Wilson HG, Gilbertz DA. Rates of and factors associated with recurrence of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2000;283:1591–1596. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakketeig LS, Hoffman HJ, Harley EE. The tendency to repeat gestational age and birth weight in successive births. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:1086–1103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter TF, Fraser AM, Hunter CY, Ward RH, Varner MW. The risk of preterm birth across generations. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:63–67. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkvist A, Mogren I, Högberg U. Familial patterns in birth characteristics: impact on individual and population risks. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:248–254. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuck TA, Lai Y, Meis PJ, Sibai B, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Iams JD, Caritis SN, O’Sullivan MJ, Wapner RJ, Mercer B, Ramin SM, Peaceman AM. Admixture mapping to identify spontaneous preterm birth susceptibility loci in African Americans. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1078–1084. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318214e67f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H-J, Hong X, Chen J, Liu X, Pearson C, Ortiz K, Hirsch E, Heffner L, Weeks DE, Zuckerman B, Wang X. Role of African ancestry and gene-environment interactions in predicting preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1081–1089. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823389bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausson B, Lichtenstein P, Cnattingius S. Genetic influence on birthweight and gestational length determined by studies in offspring of twins. BJOG. 2000;107:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar SA, Macones GA, Mitchell LE, Martin NG. Genetic influences on premature parturition in an Australian twin sample. Twin Res. 2000;3:80–82. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistka ZA-F, DeFranco EA, Ligthart L, Willemsen G, Plunkett J, Muglia LJ, Boomsma DI. Heritability of parturition timing: an extended twin design analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.014. e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Avila C, Santhanam U, Sehgal PB. Amniotic fluid interleukin 6 in preterm labor. Association with infection. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1392–1400. doi: 10.1172/JCI114583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiyuan Z, Li W. Study of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in maternal serum and amniotic fluid of patients with premature rupture of membranes. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:491–494. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1998.26.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo G, Capponi A, Vlachopoulou A, Angelini E, Grassi C, Romanini C. Interleukin-6 concentrations in cervical secretions in the prediction of intrauterine infection in preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:91–95. doi: 10.1159/000010009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett J, Muglia LJ. Genetic contributions to preterm birth: Implications from epidemiological and genetic association studies. Ann Med. 2008;40:167–179. doi: 10.1080/07853890701806181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A, Tatter SB, May LT, Sehgal PB. Activation of the human “beta 2-interferon/hepatocyte-stimulating factor/interleukin 6” promoter by cytokines, viruses, and second messenger agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6701–6705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki H, Akira S, Tanabe O, Nakajima T, Shimamoto T, Hirano T, Kishimoto T. Constitutive and interleukin-1 (IL-1)-inducible factors interact with the IL-1-responsive element in the IL-6 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2757–2764. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry CF, Loukaci V, Green FR. Cooperative influence of genetic polymorphisms on interleukin 6 transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18138–18144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huth C, Illig T, Herder C, Gieger C, Grallert H, Vollmert C, Rathmann W, Hamid YH, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Thorand B, Meisinger C, Doring A, Klopp N, Gohlke H, Lieb W, Hengstenberg C, Lyssenko V, Groop L, Ireland H, Stephens JW, Wernstedt Asterholm I, Jansson J-O, Boeing H, Mohlig M, Stringham HM, Boehnke M, Tuomilehto J, Fernandez-Real J-M, Lopez-Bermejo A. Joint analysis of individual participants’ data from 17 studies on the association of the IL6 variant -174G>C with circulating glucose levels, interleukin-6 levels, and body mass index. Ann Med. 2009;41:128–138. doi: 10.1080/07853890802337037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJP, Humphries SE. Cytokine and cytokine receptor gene polymorphisms and their functionality. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:43–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman D, Faulds G, Jeffery R, Mohamed-Ali V, Yudkin JS, Humphries S, Woo P. The effect of novel polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene on IL-6 transcription and plasma IL-6 levels, and an association with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1369–1376. doi: 10.1172/JCI2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simhan HN, Krohn MA, Roberts JM, Zeevi A, Caritis SN. Interleukin-6 promoter -174 polymorphism and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:915–918. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annells MF, Hart PH, Mullighan CG, Heatley SL, Robinson JS, Bardy P, McDonald HM. Interleukins-1, -4, -6, -10, tumor necrosis factor, transforming growth factor-beta, FAS, and mannose-binding protein C gene polymorphisms in Australian women: Risk of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:2056–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez LM, Sammel MD, Appleby DH, Elovitz MA, Baldwin DA, Jeffcoat MK, Macones GA, Parry S. Evidence of a gene-environment interaction that predisposes to spontaneous preterm birth: a role for asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and DNA variants in genes that control the inflammatory response. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:386. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.042. e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper M, Zheng SL, Thom E, Klebanoff MA, Thorp J, Sorokin Y, Varner MW, Iams JD, Dinsmoor M, Mercer BM, Rouse DJ, Ramin SM, Anderson GD. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and length of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:125–130. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318202b2ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härtel C, Finas D, Ahrens P, Kattner E, Schaible T, Müller D, Segerer H, Albrecht K, Möller J, Diedrich K, Göpel W. Polymorphisms of genes involved in innate immunity: association with preterm delivery. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:911–915. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollegaard MV, Grove J, Thorsen P, Wang X, Mandrup S, Christiansen M, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Wojdemann KR, Tabor A, Attermann J, Hougaard DM. Polymorphisms in the tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1-beta promoters with possible gene regulatory functions increase the risk of preterm birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:1285–1290. doi: 10.1080/00016340802468340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Velez DR, Simhan H, Ryckman K, Jiang L, Thorsen P, Vogel I, Jacobsson B, Merialdi M, Williams SM, Fortunato SJ. Multilocus interactions at maternal tumor necrosis factor-alpha, tumor necrosis factor receptors, interleukin-6 and interleukin-6 receptor genes predict spontaneous preterm labor in European-American women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1616–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura E, Mattar R, De Souza E, Torloni MR, Gonçalves-Primo A, Daher S. Inflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms and spontaneous preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;80:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereyra S, Velazquez T, Bertoni B, Sapiro R. Rapid multiplex high resolution melting method to analyze inflammatory related SNPs in preterm birth. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer EM, Gentile DA, Zeevi A, Pillage G, Huo D, Skoner DP. Role of single nucleotide polymorphisms of cytokine genes in spontaneous preterm delivery. Hum Immunol. 2006;67:915–923. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.08.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonek F, Metzenbauer M, Hafner E, Philipp K, Tempfer C. Interleukin 6–174 GC promoter polymorphism and pregnancy complications: results of a prospective cohort study in 1626 pregnant women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez DR, Menon R, Thorsen P, Jiang L, Simhan H, Morgan N, Fortunato SJ, Williams SM. Ethnic differences in interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL6 receptor genes in spontaneous preterm birth and effects on amniotic fluid protein levels. Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71:586–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Bohidar NR, Ciminera JL. Mantel-Haenszel analyses of litter-matched time-to-response data, with modifications for recovery of interlitter information. Cancer Res. 1977;37:3863–3868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CB, Lehrnbecher T, Samuels S, Stein S, Mol F, Metcalf JA, Wyvill K, Steinberg SM, Kovacs J, Blauvelt A, Yarchoan R, Chanock SJ. An IL6 promoter polymorphism is associated with a lifetime risk of development of Kaposi sarcoma in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Blood. 2000;96:2562–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Real JM, Broch M, Vendrell J, Richart C, Ricart W. Interleukin-6 gene polymorphism and lipid abnormalities in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1334–1339. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.3.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen OP, Nolsøe RL, Larsen L, Gjesing AMP, Johannesen J, Larsen ZM, Lykkesfeldt AE, Karlsen AE, Pociot F, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Association of a functional 17beta-estradiol sensitive IL6-174GC promoter polymorphism with early-onset type 1 diabetes in females. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1101–1110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möhlig M, Boeing H, Spranger J, Osterhoff M, Kroke A, Fisher E, Bergmann MM, Ristow M, Hoffmann K, Pfeiffer AFH. Body mass index and C-174G interleukin-6 promoter polymorphism interact in predicting type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1885–1890. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illig T, Bongardt F, Schöpfer A, Müller-Scholze S, Rathmann W, Koenig W, Thorand B, Vollmert C, Holle R, Kolb H, Herder C. Significant association of the interleukin-6 gene polymorphisms C-174G and A-598G with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5053–5058. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier M-T, Paradis A-M, Tchernof A, Bergeron J, Prud’homme D, Després J-P, Vohl M-C. The interleukin 6-174GC polymorphism is associated with indices of obesity in men. J Hum Genet. 2003;48:14–19. doi: 10.1007/s100380300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawczenko A, Azooz O, Paraszczuk J, Idestrom M, Croft NM, Savage MO, Ballinger AB, Sanderson IR. Intestinal inflammation-induced growth retardation acts through IL-6 in rats and depends on the -174 IL-6 GC polymorphism in children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13260–13265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503589102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell JK, Coop G, Novembre J, Kudaravalli S, Li JZ, Absher D, Srinivasan BS, Barsh GS, Myers RM, Feldman MW, Pritchard JK. Signals of recent positive selection in a worldwide sample of human populations. Genome Res. 2009;19:826–837. doi: 10.1101/gr.087577.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop G, Pickrell JK, Novembre J, Kudaravalli S, Li J, Absher D, Myers RM, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW, Pritchard JK. The role of geography in human adaptation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Pickrell JK, Coop G. The genetics of human adaptation: hard sweeps, soft sweeps, and polygenic adaptation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R208–R215. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collaboration. RevMan 5.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp. LP. STATA Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All the included and excluded papers and the reasons of inclusion or exclusion.

Distribution of SNPs allele frequency differences for three continental populations.

Meta-regression analysis for (a) maternal genotype studies, (b) fetal genotype studies.

MOOSE checklist.