Abstract

Aims

Niacin has potentially favourable effects on lipids, but its effect on cardiovascular outcomes is uncertain. HPS2-THRIVE is a large randomized trial assessing the effects of extended release (ER) niacin in patients at high risk of vascular events.

Methods and results

Prior to randomization, 42 424 patients with occlusive arterial disease were given simvastatin 40 mg plus, if required, ezetimibe 10 mg daily to standardize their low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-lowering therapy. The ability to remain compliant with ER niacin 2 g plus laropiprant 40 mg daily (ERN/LRPT) for ∼1 month was then assessed in 38 369 patients and about one-third were excluded (mainly due to niacin side effects). A total of 25 673 patients were randomized between ERN/LRPT daily vs. placebo and were followed for a median of 3.9 years. By the end of the study, 25% of participants allocated ERN/LRPT vs. 17% allocated placebo had stopped their study treatment. The most common medical reasons for stopping ERN/LRPT were related to skin, gastrointestinal, diabetes, and musculoskeletal side effects. When added to statin-based LDL-lowering therapy, allocation to ERN/LRPT increased the risk of definite myopathy [75 (0.16%/year) vs. 17 (0.04%/year): risk ratio 4.4; 95% CI 2.6–7.5; P < 0.0001]; 7 vs. 5 were rhabdomyolysis. Any myopathy (definite or incipient) was more common among participants in China [138 (0.66%/year) vs. 27 (0.13%/year)] than among those in Europe [17 (0.07%/year) vs. 11 (0.04%/year)]. Consecutive alanine transaminase >3× upper limit of normal, in the absence of muscle damage, was seen in 48 (0.10%/year) ERN/LRPT vs. 30 (0.06%/year) placebo allocated participants.

Conclusion

The risk of myopathy was increased by adding ERN/LRPT to simvastatin 40 mg daily (with or without ezetimibe), particularly in Chinese patients whose myopathy rates on simvastatin were higher. Despite the side effects of ERN/LRPT, among individuals who were able to tolerate it for ∼1 month, three-quarters continued to take it for ∼4 years.

Keywords: ER niacin/laropiprant, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, secondary prevention, cardiovascular disease

See page 1254 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht064)

Introduction

Cardiovascular risk remains elevated in some high-risk patients even after lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) with statins, controlling blood pressure and diabetes, and stopping smoking.1,2 Targeting other aspects of lipid metabolism, such as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, and lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)], as well as lowering LDL-C further, offers the prospect of additional cardiovascular risk reduction.3,4

Niacin has potentially beneficial effects on multiple lipid fractions

Niacin is an old drug whose lipid modification properties at high doses have been recognized for many years.5 In patients already receiving a statin, extended release (ER) niacin 2 g daily is reported to increase HDL-C by ∼20% and apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) by ∼7%, as well as reducing LDL-C, apolipoprotein B (apoB), and Lp(a) levels by ∼20% and triglycerides by ∼25%.6 Previous observational studies have demonstrated a strong positive association of cardiovascular disease risk with LDL-C and a strong inverse association with HDL-C. Randomized trials of statin therapy indicate that the LDL-C association is causal,1 but it remains uncertain whether the association with HDL-C is causal. There is also evidence for a causal association between Lp(a) and CHD, with lower Lp(a) associated with lower CHD risk.7 Niacin does, therefore, have multiple effects on lipid metabolism which might be beneficial. In addition, niacin can reduce blood pressure, but it also has potentially adverse effects on glucose metabolism.8,9

Uncertainty remains about clinical benefits of niacin in the modern era

The first large randomized trial to have assessed the effects of niacin on clinical outcomes was the coronary drug project (CDP) in 8341 post-myocardial infarction (MI) men. Allocation to niacin 3 g daily reduced total cholesterol by ∼0.7 mmol/L and this was associated with a significant 19% (95% CI 4–31%) reduction in the incidence of non-fatal MI or coronary death.10 However, the CDP was conducted more than 30 years ago, before statins and other effective cardioprotective treatments were available, making its applicability in the present day unclear. More recently, the AIM-HIGH study in 3414 high-risk patients of adding ER niacin 1.5–2.0 g daily to statin therapy was stopped prematurely because of perceived lack of benefit (hazard ratio 1.02; 95% CI 0.87–1.21),11 but the observed mean lipid differences were small (0.12 mmol/L lower LDL-C and 0.13 mmol/L higher HDL-C in the niacin group). Such changes in lipids might be expected to reduce CHD risk by at most 10%, but AIM-HIGH was too small to detect such an effect reliably.

Niacin has a number of side effects which limit its use in some people. In particular, it causes an unpleasant cutaneous vasodilatation (‘flushing’) in almost all patients who take therapeutic doses of immediate-release niacin and up to two-thirds of those taking ER niacin.12 Episodes of flushing with niacin (but not other adverse effects) are principally mediated by prostaglandin D2 release in the skin.13 Laropiprant is a specific antagonist of DP1, the prostaglandin D2 receptor, which reduces this flushing and has been shown to improve niacin tolerability.14 The HPS2-THRIVE trial is assessing the effects on cardiovascular and other major outcomes of adding the combination of ER niacin 2 g with laropiprant 40 mg (ERN/LRPT) daily to effective statin treatment in 25 673 patients with occlusive arterial disease. The present report describes the trial design, patient characteristics, and reasons for stopping study treatment, along with the information on myopathy and liver-related events that were pre-specified to be reported prior to the main clinical outcomes (see Supplementary material online).

Methods

Objectives

The primary aim of HPS2-THRIVE is to assess the effect of ER niacin 2 g plus laropiprant 40 mg daily vs. matching placebo on the time to first ‘major vascular event’ (MVE: a composite of non-fatal MI, coronary death, stroke, or arterial revascularization) among high-risk patients with pre-existing occlusive arterial disease who are receiving effective statin-based LDL-lowering therapy. Further details about secondary and tertiary assessments are available in the Data Analysis Plans (see Supplementary material online).

For the purposes of the present report, reasons for stopping study treatment were to be compared overall and also grouped by body system or affected organ. In addition, liver and muscle safety outcomes were to include two or more consecutive elevations of alanine transaminase (ALT) >3× upper limit of normal (ULN); presumed study-drug-related hepatitis; definite myopathy; rhabdomyolysis; and incipient myopathy (which indicated a high risk of, and shared a genetic predisposition with, subsequent myopathy in a previous trial15) (see Data Analysis Plans for definitions).

Eligibility

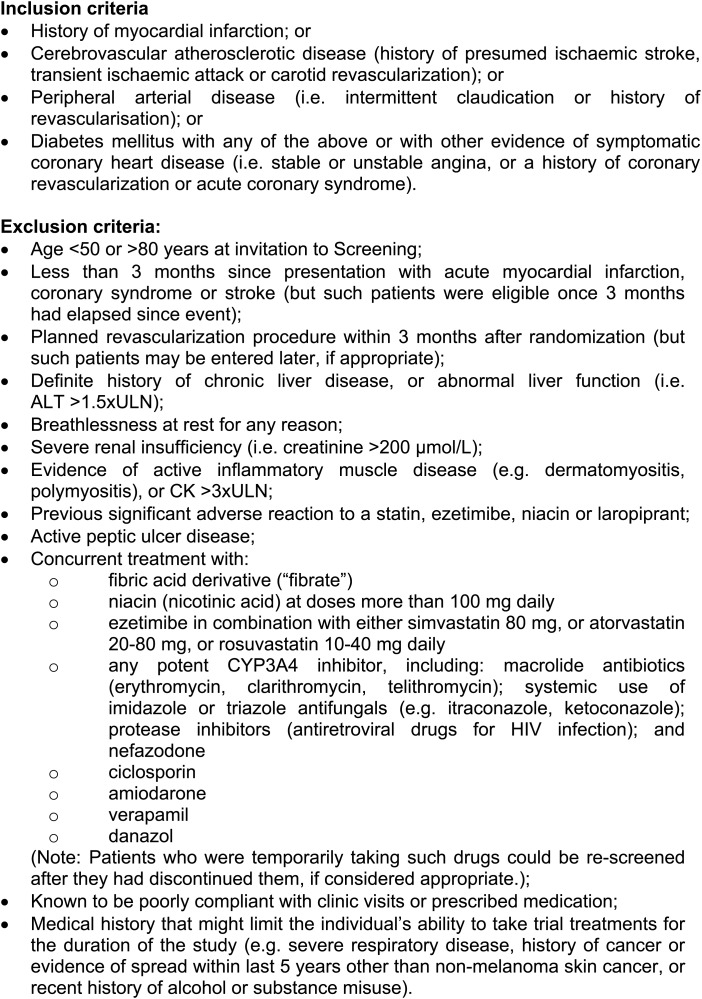

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1) were designed to allow the recruitment of a wide range of participants at high risk of vascular events while excluding those for whom the safety of simvastatin or ERN/LRPT might be a concern, or for whom more potent LDL-lowering or niacin treatment was considered to be indicated. There were no lipid inclusion criteria as HPS2-THRIVE aims to examine the effects on MVEs among participants with various lipid profiles (e.g. higher or lower LDL-C and HDL-C).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Invitation and screening

Potentially eligible patients were identified from hospital or clinic records or by local advertisement and invited to attend a clinic where specially trained study staff completed an electronic study questionnaire about their past medical history, current treatments and other factors relevant to eligibility and vascular risk. Blood pressure was measured and a blood sample taken (participants were asked to fast before attending although it was not mandated, and time since last meal was recorded) with an immediate measurement of ALT, creatine kinase (CK) and creatinine using a Reflotron Plus (Roche) dry chemistry analyser (which was found to produce values in close agreement with those obtained by the central laboratory). Patients who appeared eligible were provided with a written description of the study and invited to participate (after, if they wished, discussing it with their family or other doctors). All who agreed to participate provided their written consent and stopped any current statin therapy.

Run-in period and randomization

Prior to randomization, participants had their LDL-lowering therapy standardized in order to minimize post-randomization treatment changes. Each participant received simvastatin 40 mg daily or, if not sufficient to achieve a total cholesterol <3.5 mmol/L when measured after 4 weeks, simvastatin 40 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg daily (in each case as a single open-label tablet). In all cases, the LDL-lowering therapy given at the initial study screening visit was at least as intensive as the participant's current treatment, and those who were already receiving simvastatin 40 mg daily with total cholesterol <3.5 mmol/L or simvastatin/ezetimibe 40/10 mg daily entered the active ERN/LRPT phase of run-in directly from screening (see below). The local clinical investigators were provided with the dry chemistry total cholesterol value of each participant when taking the LDL-lowering treatment that it was proposed to be used in the trial, and asked to withdraw their patient if they did not wish them to be randomized (e.g. because the patient's lipids were not considered to be adequately controlled).

In the second part of the pre-randomization run-in phase, all participants received the addition of ER niacin 1 g plus laropiprant 20 mg daily for 4 weeks followed by ER niacin 2 g plus laropiprant 40 mg daily taken orally at night for a further 3–6 weeks. The aim of the active run-in phase was to reduce the rate of post-randomization discontinuation of study treatment and to produce a consequent improvement in statistical sensitivity for assessing any beneficial effects of prolonged treatment with ER niacin.16 It should be noted, however, that this means that the post-randomization rates of side effects and reasons for stopping study treatment relate to patients able to tolerate ∼1 month of ERN/LRPT.

Participants were randomized provided they reported taking at least 90% of their scheduled ERN/LRPT and LDL-lowering study tablets during the run-in phase and remained willing and eligible. At the randomization visit, height, weight, and waist circumference were measured, degree of flushing assessed, and history of heart failure recorded. Randomization using a minimization algorithm17 (involving age, gender, prior disease, smoking, total cholesterol, blood pressure, ethnic origin, prior statin use, diabetes, and LDL-lowering treatment) was provided by the study clinic computer which was synchronized frequently with the study database at the coordinating centre in the Clinical Trial Service Unit, Oxford via secure internet connection.

Post-randomization follow-up and safety monitoring

Study follow-up visits were conducted at 3 and 6 months following randomization and then 6 monthly. Study clinic staff systematically sought information on all serious adverse events, any non-serious adverse events considered by participants to be related to, or that resulted in stopping, study treatment, on muscle pain or weakness, and on symptoms suggestive of hepatitis (nausea, vomiting, or jaundice). The coordinating centre sought further details from the participant's medical records about all reports that might relate to MVEs or safety outcomes, and from national registries (where available) about cancers and the certified causes of any deaths. All such information was reviewed by coordinating centre clinicians (blind to treatment allocation) and events adjudicated according to pre-specified criteria.

Compliance with study treatment was assessed and, if relevant, a reason for discontinuation was recorded. Participants prescribed contra-indicated drugs (non-study niacin or fibrates) had their randomized treatment (ERN/LRPT or placebo) stopped. Those who were prescribed a non-study statin or drugs known to increase the risk of statin-induced myopathy had their study LDL-lowering treatment stopped. At each follow-up visit, dry chemistry analysers were used to measure ALT and, if ALT >1.5× ULN or muscle symptoms were reported, also CK. Externally measured CK and ALT results associated with events of interest were also recorded in the study database and included in these analyses. Consecutive elevations of ALT >3× ULN, any ALT >10× ULN or ALT >3× ULN with bilirubin ≥2× ULN without clear alternative causes led to permanent discontinuation of randomized treatment. Persistent CK >10× ULN without muscle symptoms or >5× ULN with muscle symptoms led to discontinuation of both study treatments. Other elevations of ALT or CK were managed (including recall visits to reassess symptoms and measure ALT and CK levels) after review by coordinating centre clinicians in collaboration with doctors at the local site, with the aim of minimizing myopathy or liver injury risk.

Central laboratory analyses and storage

Blood and urine samples were collected at the end of the LDL-C standardization phase (while participants were taking their allocated LDL-lowering therapy) and sent to a central laboratory for analysis of a lipid profile, creatinine, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), full blood count (in the UK only) and urinary albumin:creatinine ratio, and for long-term storage in liquid nitrogen of plasma, urine, and buffy coat aliquots (for possible future analyses). Blood samples were also taken for central laboratory analysis at the randomization visit and 3 month post-randomization visit (UK only), and, along with a urine sample, in a random 5% sample of participants each year, in all participants at a median follow-up of 1 year for their region and at the final follow-up visit. Details of assay methodology are given in the appendix (see Supplementary material online).

Statistical methods

Pre-specified assessments involve comparisons among all randomized participants in their originally allocated treatment group, irrespective of compliance [i.e. intention-to-treat (ITT)] up to the point of censoring for these analyses. ITT comparisons were made to assess reliably the modest differences between active treatment and placebo in various common outcomes (rather than to detect large effects on rare outcomes which might be assessed by non-randomized comparisons). Numbers of participants and, where appropriate, proportions or annual rates based on person years in the study are presented. Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate risk ratios. For interpretation of these safety analyses, allowance has been made for multiple hypothesis testing by taking into account the nature of the event and evidence from other studies (see Supplementary material online). Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

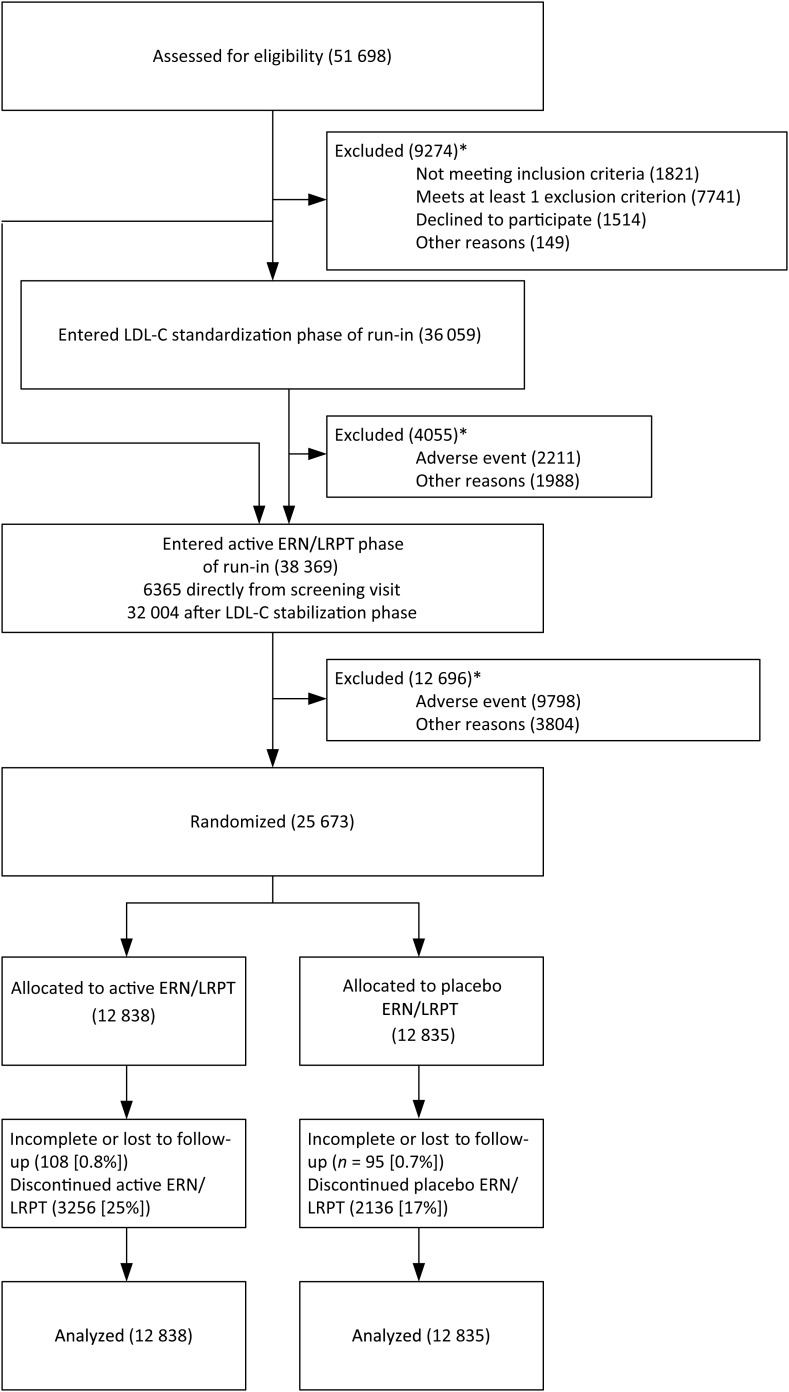

After relevant ethics and regulatory approvals had been obtained, study sites were established in China (72 hospitals or clinics), UK (89), Denmark (22), Finland (10), Norway (21), and Sweden (31). A total of 51 698 patients attended the study screening clinics: 16 861 in China, 24 396 in the UK, and 10 441 in Scandinavia; and 97, 66, and 95%, respectively, entered the run-in (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trial profile: Flow of participants through the trial. Participants receiving simvastatin 40 mg (with total cholesterol <3.5 mmol/L) or ezetimibe/simvastatin 10/40 mg prior to screening entered the active ER niacin/laropiprant phase of the run-in immediately after the screening visit. *Participants may have more than one reason for being excluded.

Pre-randomization run-in

Overall, 4055 (11.2%) of the 36 059 individuals who entered the LDL-lowering standardization phase withdrew prior to the ERN/LRPT phase (Table 1). Serious adverse reactions were given as reasons for withdrawal by six patients: five myopathy and one hepatitis. Of the 38 369 individuals who entered the active ERN/LRPT phase, 12 696 (33.1%) withdrew prior to randomization. Overall, medical reasons were four times as commonly cited as a reason for withdrawing during the active ERN/LRPT phase (average duration: 7.4 weeks) than during the LDL-lowering phase (4.6 weeks). As expected with niacin, the most common reasons were skin reactions (mainly pruritus, rashes, and flushing), and gastrointestinal symptoms (mainly nausea, and diarrhoea). Serious adverse reactions were given as reasons for withdrawal by 69 patients: 29 myopathy; 10 (pre-)syncopal; 8 skin-related; 6 gastrointestinal; 6 allergic; 3 diabetes related; 3 biochemical; 2 cardiac; and 2 other events. Non-medical reasons were also more commonly reported in the active ERN/LRPT phase, with an excess of difficulty swallowing tablets.

Table 1.

Reasons for withdrawal from pre-randomization run-in

| LDL-lowering therapy alone | LDL-lowering therapy plus active ERN/LRPT | |

|---|---|---|

| Number entering phase | 36 059 | 38 369 |

| Mean duration of phase (weeks) | 4.6 | 7.4 |

| Medical reasons | ||

| Skin | ||

| Pruritis | 80 (0.2%) | 2536 (6.6%) |

| Rash | 65 (0.2%) | 1416 (3.7%) |

| Flushing | 20 (<0.1%) | 646 (1.7%) |

| Other skin | 13 (<0.1%) | 192 (0.5%) |

| Any skin reason | 170 (0.5%) | 4326 (11.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | ||

| Any upper GIa | 208 (0.6%) | 1108 (2.9%) |

| Any lower GI | 170 (0.5%) | 883 (2.3%) |

| Other GI | 98 (0.3%) | 278 (0.7%) |

| Any gastrointestinal reason | 454 (1.3%) | 2117 (5.5%) |

| Hepatobiliary | ||

| Abnormal alanine transaminaseb | 223 (0.6%) | 472 (1.2%) |

| Other hepatobiliary | 2 (<0.1%) | 9 (<0.1%) |

| Any hepatobiliary reason | 225 (0.6%) | 481 (1.3%) |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Muscle symptomsa | 268 (0.7%) | 498 (1.3%) |

| Rheumatological | 65 (0.2%) | 196 (0.5%) |

| Gout | 5 (<0.1%) | 60 (0.2%) |

| Abnormal creatine kinase | 12 (<0.1%) | 33 (<0.1%) |

| Other musculoskeletal | 397 (1.1%) | 381 (1.0%) |

| Any musculoskeletal reason | 704 (2.0%) | 1096 (2.9%) |

| Diabetes | ||

| New-onset diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (<0.1%) |

| Major diabetes complication | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (<0.1%) |

| Other diabetes-related reason | 26 (<0.1%) | 656 (1.7%) |

| Any diabetes-related reason | 26 (<0.1%) | 664 (1.7%) |

| Other medical | ||

| Pre-syncope/syncope | 55 (0.2%) | 261 (0.7%) |

| Palpitations | 36 (<0.1%) | 123 (0.3%) |

| Other cardiovascular | 186 (0.5%) | 436 (1.1%) |

| Respiratory | 25 (<0.1%) | 118 (0.3%) |

| Cancer | 12 (<0.1%) | 45 (0.1%) |

| Other | 380 (1.1%) | 1277 (3.3%) |

| Contraindicated medication | 25 (<0.1%) | 49 (0.1%) |

| Medical advice | 90 (0.2%) | 157 (0.4%) |

| Planned revascularization | 8 (<0.1%) | 45 (0.1%) |

| Any other medical reason | 802 (2.2%) | 2354 (6.1%) |

| Any medical reason | 2211 (6.1%) | 9798 (25.5%) |

| Non-medical reasons | ||

| Patient wishes/did not attend | 1502 (4.2%) | 2403 (6.3%) |

| Difficulty swallowing tablets | 68 (0.2%) | 746 (1.9%) |

| Other | 639 (1.8%) | 1317 (3.4%) |

| Any non-medical reason | 1988 (5.5%) | 3804 (9.9%) |

| Any reason | 4055 (11.2%) | 12 696 (33.1%) |

Participants may report more than one reason for withdrawal. Percentages are shown relative to the number of participants entering the phase. LDL-lowering therapy alone: LDL stabilization on simvastatin 40 mg or ezetimibe/simvastatin 10/40 mg daily. LDL-lowering therapy plus active ERN/L: LDL-lowering treatment plus ER niacin/laropiprant (1 g daily for 4 weeks increasing to 2 g daily for 4 weeks).

aIncludes routinely sought symptoms at run-in and randomization visits.

bMeasured at run-in and randomization visits: participants were excluded if >2× upper limit of normal.

Baseline characteristics of randomized participants

Between April 2007 and July 2010, a total of 25 673 people were randomized: 10 932 from China, 8035 from the UK, and 6706 from Scandinavia (see Table 2 and Supplementary material online, Table S1). There were a number of differences between the participants in China and Europe (e.g. those from China were more likely to have prior cerebrovascular disease or diabetes and to smoke, and less likely to drink alcohol or be on a statin prior to screening, although the use of non-study treatments was similar). Blood lipid levels on the background LDL-lowering therapy (prior to the start of the pre-randomization ERN/LRPT) are shown in Table 3 and Supplementary material online, Table S2. The mean total cholesterol was 3.32 (SD 0.57) mmol/L, LDL-C was 1.64 (0.44) mmol/L, HDL-C was 1.14 (0.29) mmol/L and triglycerides were 1.43 (0.84) mmol/L, with lower average values among the participants in China. Following the addition of run-in treatment with ERN/LRPT, there were reductions in LDL-C of 0.34 (SE 0.003) mmol/L, apoB of 0.10 (0.001) g/L, and triglycerides of 0.26 (0.004) mmol/L, and increases in HDL-C of 0.18 (0.001) mmol/L and apoA1 of 0.06 (0.001) g/L, with similar proportional changes in China and Europe.

Table 2.

Selected baseline characteristics of randomized participants

| China | Europe | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomized | 10 932 | 14 741 | 25 673 |

| Mean age (SD) | 63.4 (7.6) | 65.9 (7.2) | 64.9 (7.5) |

| Male (%) | 8680 (79.4%) | 12 549 (85.1%) | 21 229 (82.7%) |

| History | |||

| Coronary disease | 8407 (76.9%) | 11 730 (79.6%) | 20 137 (78.4%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4462 (40.8%) | 3708 (25.2%) | 8170 (31.8%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 508 (4.6%) | 2706 (18.4%) | 3214 (12.5%) |

| Diabetes mellitusa | 4611 (42.2%) | 3688 (25.0%) | 8299 (32.3%) |

| Treated hypertension | 6894 (63.1%) | 9025 (61.2%) | 15 919 (62.0%) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 4197 (38.4%) | 4529 (30.7%) | 8726 (34.0%) |

| Former | 4248 (38.9%) | 8089 (54.9%) | 12 337 (48.1%) |

| Current | 2487 (22.7%) | 2123 (14.4%) | 4610 (18.0%) |

| Alcohol intake (units/week) | |||

| None | 9516 (87.0%) | 5669 (38.5%) | 15 185 (59.1%) |

| >0 <21 | 1243 (11.4%) | 7780 (52.8%) | 9023 (35.1%) |

| ≥21 | 173 (1.6%) | 1292 (8.8%) | 1465 (5.7%) |

| Physical measurements | |||

| Mean systolic blood pressure (mmHg) (SD) | 142.8 (22.4) | 144.1 (20.1) | 143.5 (21.1) |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) (SD) | 79.9 (12.2) | 81.1 (10.7) | 80.6 (11.4) |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) (SD) | 26.2 (3.3) | 28.8 (5.0) | 27.7 (4.5) |

| Medications | |||

| Current statin use (years) | |||

| None | 5625 (51.5%) | 566 (3.8%) | 6191 (24.1%) |

| >0 <3 | 4339 (39.7%) | 3811 (25.9%) | 8150 (31.7%) |

| ≥3 | 968 (8.9%) | 10 364 (70.3%) | 11 332 (44.1%) |

| Study LDL-lowering therapy (daily) | |||

| Simvastatin 40 mg | 8051 (73.6%) | 5491 (37.2%) | 13 542 (52.7%) |

| Ezetimibe/simvastatin 10/40 mg | 2881 (26.4%) | 9250 (62.8%) | 12 131 (47.3%) |

| Non-study medications | |||

| Aspirin | 9417 (86.1%) | 12 742 (86.4%) | 22 159 (86.3%) |

| Other antiplatelet | 1910 (17.5%) | 2727 (18.5%) | 4637 (18.1%) |

| ACEi or ARBb | 4657 (42.6%) | 10 090 (68.4%) | 14 747 (57.4%) |

| Diuretic | 969 (8.9%) | 3750 (25.4%) | 4719 (18.4%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 3454 (31.6%) | 3638 (24.7%) | 7092 (27.6%) |

| Beta blocker | 5635 (51.5%) | 9495 (64.4%) | 15 130 (58.9%) |

aSelf-reported, or baseline plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L if fasted <8 h or ≥7.0 mmol/L if fasted ≥8 h, or baseline HbA1c ≥48 mmol/mol, or use of hypoglycaemic medication at randomization.

bAngiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or angiotensin-2 receptor blocker (ARB).

Table 3.

Effects (means and standard errors) of ER niacin/laropiprant on lipid measures after 8 week pre-randomization run-in

| China | Europe | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | |||

| Baseline (mmol/L) | 3.14 (0.005) | 3.45 (0.005) | 3.32 (0.004) |

| Absolute change (mmol/L) | −0.23 (0.006) | −0.18 (0.005) | −0.20 (0.004) |

| Per cent change (%) | −6.5 (0.19) | −4.5 (0.15) | −5.4 (0.12) |

| LDL-C | |||

| Baseline (mmol/L) | 1.51 (0.004) | 1.74 (0.004) | 1.64 (0.003) |

| Absolute change (mmol/L) | −0.32 (0.005) | −0.36 (0.004) | −0.34 (0.003) |

| Per cent change (%) | −20.1 (0.31) | −19.8 (0.23) | −19.9 (0.19) |

| ApoB | |||

| Baseline (g/L) | 0.65 (0.001) | 0.70 (0.001) | 0.68 (0.001) |

| Absolute change (g/L) | −0.10 (0.001) | −0.10 (0.001) | −0.10 (0.001) |

| Per cent change (%) | −13.8 (0.21) | −13.2 (0.16) | −13.5 (0.13) |

| HDL-C | |||

| Baseline (mmol/L) | 1.06 (0.002) | 1.19 (0.003) | 1.14 (0.002) |

| Absolute change (mmol/L) | 0.15 (0.002) | 0.20 (0.002) | 0.18 (0.001) |

| Per cent change (%) | 15.9 (0.20) | 17.6 (0.14) | 16.9 (0.12) |

| ApoA1 | |||

| Baseline (g/L) | 1.38 (0.002) | 1.51 (0.002) | 1.45 (0.002) |

| Absolute change (g/L) | 0.04 (0.002) | 0.08 (0.001) | 0.06 (0.001) |

| Per cent change (%) | 3.8 (0.12) | 5.6 (0.10) | 4.8 (0.08) |

| Triglycerides | |||

| Baseline (mmol/L) | 1.40 (0.008) | 1.46 (0.007) | 1.43 (0.005) |

| Absolute change (mmol/L) | −0.29 (0.007) | −0.24 (0.006) | −0.26 (0.004) |

| Per cent change (%) | −14.4 (0.42) | −10.2 (0.31) | −12.0 (0.25) |

| Median per cent change (IQR)a | −23.4 (44.54) | −17.0 (40.68) | −19.5 (42.47) |

Changes are shown between measures taken at the baseline visit (after stabilization on LDL-lowering therapy alone) and the randomization visit (after 8 weeks of LDL-lowering plus active ER niacin/laropiprant 1 g daily for 4 weeks increasing to 2 g daily for 4 weeks). At the baseline visit 64.3% of participants reported fasting for >8 h. At the randomization visit 29.6% of participants reported fasting for >8 h.

aThe median per cent change and the interquartile range (IQR) are reported as the per cent change in triglycerides is highly skewed.

Compliance with background LDL-lowering therapy

The present analyses are based on follow-up to the scheduled end of the study treatment period, by which time there was median follow-up of 3.9 years (mean 3.6 years). The proportion of participants reporting taking at least 80% of their study LDL-lowering treatment was 92, 89, and 85% after 1, 2, and 3 years follow-up respectively. The proportion who stopped was slightly higher among participants allocated ERN/LRPT than those allocated placebo (13.7% vs. 11.7%, P < 0.0001). Participants who stopped study LDL-lowering therapy were advised to discuss the use of non-study statins with their own doctors (18% of the participants in China who had stopped started non-study statin compared with 73% of the participants in Europe).

Safety and tolerability of ER niacin/laropiprant

By 3.9 years of follow-up, 25.4% of the participants allocated active ERN/LRPT had stopped their randomized treatment compared with 16.6% of those on placebo (Table 4). Most of this excess was attributed to medical reasons (16.4% vs. 7.9%), chiefly skin and gastrointestinal reasons, with some differences in the patterns seen in China and Europe (Supplementary material online, Table S3).

Table 4.

Reasons for stopping randomized treatment during follow-up

| ERN/LRPT | Placebo | Excessa (SE) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomized | 12 838 | 12 835 | ||

| Total not continuing randomized treatment | 3256 (25.4%) | 2136 (16.6%) | 8.7% (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Medical reasons | ||||

| Skin | ||||

| Pruritis | 432 | 90 | ||

| Rash | 132 | 47 | ||

| Flushing | 106 | 14 | ||

| Other skin | 27 | 9 | ||

| Any skin reason | 697 (5.4%) | 160 (1.2%) | 4.2% (0.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | ||||

| Any upper GI | 227 | 104 | ||

| Any lower GI | 205 | 73 | ||

| Other GI | 63 | 42 | ||

| Any GI reason | 495 (3.9%) | 219 (1.7%) | 2.1% (0.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Hepatobiliary | ||||

| Abnormal alanine transaminase | 38 | 30 | ||

| Other hepatobiliary | 14 | 13 | ||

| Any hepatobiliary reason | 52 (0.4%) | 43 (0.3%) | 0.1% (0.1%) | 0.36 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||

| Muscle symptoms | 151 | 90 | ||

| Rheumatological | 18 | 21 | ||

| Gout | 26 | 8 | ||

| Abnormal creatine kinase | 25 | 5 | ||

| Other musculoskeletal | 5 | 4 | ||

| Any musculoskeletal reason | 225 (1.8%) | 128 (1.0%) | 0.8% (0.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| New-onset diabetes mellitus | 13 | 5 | ||

| Major diabetes complication | 2 | 0 | ||

| Other diabetes-related reason | 104 | 45 | ||

| Any diabetes-related reason | 119 (0.9%) | 50 (0.4%) | 0.5% (0.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Other medical | ||||

| Pre-syncope/syncope | 23 | 16 | ||

| Palpitations | 8 | 2 | ||

| Other cardiovascular | 75 | 80 | ||

| Respiratory | 20 | 13 | ||

| Cancer | 65 | 62 | ||

| Other | 185 | 150 | ||

| Contraindicated medication | 9 | 4 | ||

| Medical advice | 135 | 94 | ||

| Any other medical reason | 520 (4.1%) | 421 (3.3%) | 0.8% (0.2%) | 0.001 |

| Any medical reason | 2107 (16.4%) | 1020 (7.9%) | 8.5% (0.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Non-medical reasons | ||||

| Patient wishes | 626 | 580 | ||

| Difficulty swallowing tablets | 258 | 361 | ||

| Other | 265 | 175 | ||

| Any non-medical reason | 1149 (8.9%) | 1116 (8.7%) | 0.3% (0.4%) | 0.47 |

| Any reason for stopping | 3256 (25.4%) | 2136 (16.6%) | 8.7% (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

aExcess is defined as the absolute percentage of patients who had the event in the ERN/LRPT group minus the percentage who had the event in the placebo group.

*P-values are calculated from z tests comparing the proportion of patients who had the event in the ERN/LRPT group with the proportion of patients who had the event in the placebo group.

Skin

Skin-related reasons for stopping the randomized treatment were about four times more common among participants allocated ERN/LRPT (5.4% vs. 1.2%: Table 4), with a bigger excess among participants in Europe. Most of this excess was due to pruritis (3.4% vs. 0.7%), with the remainder attributed to rash (1.0% vs. 0.4%) and flushing (0.8% vs. 0.1%). Most of the rashes were maculopapular (although blistering occurred in a few participants), typically resolving within a few days of stopping study treatment (although occasionally taking several weeks), and with only 14 cases resulting in hospitalization.

Gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary

Gastrointestinal reasons for stopping the randomized treatment were about twice as common among participants allocated ERN/LRPT (3.9% vs. 1.7%: Table 4). Most of this excess was attributed to indigestion and diarrhoea, which did not usually result in hospital admission. There was no difference between the treatment groups in the numbers of participants who stopped for any hepatobiliary reasons, but allocation to ERN/LRPT approximately doubled the incidence of raised transaminases detected at routine follow-up visits (Table 5): ALT >3× ULN in 0.30%/year vs. 0.14%/year. Consecutive ALT >3× ULN within 2–7 days were seen in 0.19%/year vs. 0.07%/year. This excess of raised ALT was seen chiefly among the participants in China: for example, excess of consecutive ALT >3× ULN of 0.24%/year compared with 0.02%/year in Europe; Supplementary material online, Tables S4 and S5). Furthermore, this excess was markedly attenuated after exclusion of participants with muscle damage (which can elevate ALT levels): for example, excess of consecutive ALT >3× ULN in the absence of detected muscle damage of 0.07%/year in China vs. 0.02% in Europe. The more serious hepatobiliary combination of ALT >3× ULN plus bilirubin ≥2× ULN was similar in the two treatment groups either when detected routinely or from all results, with similar rates in China and Europe. There were 36 cases of hepatitis recorded (27 in China; 9 in Europe), of which 20 were attributed to viral and 16 to non-viral causes; only 6 of the non-viral cases (4 in China; 2 in Europe) had no alternative cause identified, 4 (0.01%) allocated ERN/LRPT vs. 2 (0.005%) allocated placebo. All six cases had ALT >10× ULN and four (2 vs. 2) also had bilirubin ≥2× ULN; all were receiving randomized treatment at the time of the event and all of them recovered. Only one man, who was found to have underlying chronic liver disease, was significantly unwell and developed a coagulopathy (but not encephalopathy).

Table 5.

Liver- and muscle-related events (per cent per year) during follow-up

| ERN/LRPT | Placebo | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomized | 12 838 | 12 835 | |

| Person years follow-up | 46 239 | 46 359 | |

| Abnormal alanine transaminase | |||

| Results collected at routine visits | |||

| >3 ≤5× ULN | 111 (0.24) | 47 (0.10) | |

| >5 ≤10× ULN | 23 (0.05) | 15 (0.03) | |

| >10× ULN | 6 (0.01) | 5 (0.01) | |

| Any >3× ULN | 140 (0.30) | 67 (0.14) | <0.0001 |

| Any >3× ULN without muscle damagea | 124 (0.27) | 65 (0.14) | <0.0001 |

| >3× ULN + bilirubin ≥2× ULN | 3 (<0.01) | 5 (0.01) | 0.72 |

| All resultsb | |||

| >3 ≤5× ULN | 190 (0.41) | 76 (0.16) | |

| >5 ≤10× ULN | 81 (0.18) | 35 (0.08) | |

| >10× ULN | 44 (0.10) | 22 (0.05) | |

| Any >3× ULN | 315 (0.68) | 133 (0.29) | <0.0001 |

| Any >3× ULN without muscle damagea | 234 (0.51) | 119 (0.26) | <0.0001 |

| Consecutive >3× ULN | 88 (0.19) | 34 (0.07) | <0.0001 |

| Consecutive >3× ULN without muscle damagea | 48 (0.10) | 30 (0.06) | 0.04 |

| >3× ULN + bilirubin ≥2× ULN | 14 (0.03) | 18 (0.04) | 0.48 |

| Myopathy | |||

| Definite myopathy | |||

| Rhabdomyolysis | 7 (0.02) | 5 (0.01) | |

| Any definite myopathy | 75 (0.16) | 17 (0.04) | <0.0001 |

| Incipient myopathyc | |||

| Symptomatic | 23 (0.05) | 12 (0.03) | |

| Asymptomatic | 59 (0.13) | 10 (0.02) | |

| Any incipient myopathy | 81 (0.18) | 21 (0.05) | <0.0001 |

| Any myopathyd | 155 (0.34) | 38 (0.08) | <0.0001 |

aMuscle damage defined as simultaneous creatine kinase >5× baseline and >3× ULN (within 7 days) of the ALT abnormality or diagnosis of myopathy (within 28 days).

bIncludes results collected at routine and recall visits as well as external reports.

cIncipient myopathy with no definite myopathy within 28 days.

dOf these individuals 180/193 were taking randomized treatment and 191/193 were taking study or non-study LDL-lowering treatment at the time of their first myopathy event.

*P-values are calculated from z tests comparing the proportion of patients who had the event in the ERN/LRPT group with the proportion of patients who had the event in the placebo group.

Diabetes

Diabetic complications (typically hyperglycaemia) were about twice as common as a reason for stopping randomized treatment in participants allocated ERN/LRPT (0.9% vs. 0.4%: Table 4). More of these events led to hospitalization in China than in Europe, perhaps indicating a different threshold for hospitalization in the different regions. Participants who developed diabetes mellitus were encouraged to continue their study treatment and this was rarely given as a reason for stopping.

Muscle

Overall, musculoskeletal symptoms were only slightly more commonly given as a reason for stopping study treatment among participants allocated ERN/LRPT (1.8% vs. 1.0%: Table 4). However, compared with the placebo group, the risk ratio for definite myopathy with ERN/LRPT was 4.4 (95% CI 2.6–7.5; P < 0.0001; 0.16%/year vs. 0.04%/year: Table 5); all of these patients had both their study LDL-lowering and randomized treatments stopped. The excess risk was greater in the first year (0.29%/year vs. 0.04%/year) than in subsequent years (0.11%/year vs. 0.04%/year). In addition, the risk ratio for incipient myopathy was 3.9 (95% CI 2.4–6.3; P < 0.0001; 0.18%/year vs. 0.05%/year); these patients were typically advised to stop their randomized treatments and only one went on to develop definite myopathy. Overall, the risk ratio for any (definite or incipient) myopathy was 4.1 (95% CI 2.9–5.9; P < 0.0001). (Restricting this analysis to the 180 participants who were receiving randomized treatment at the time of the myopathy did not alter the results materially.) Most of these cases had relatively mild symptoms and were managed as outpatients, but rhabdomyolysis—which always required hospitalization—occurred in 7 (0.02%/year) participants allocated active ERN/LRPT vs. 5 (0.01%/year) allocated placebo (RR 1.4; 95% CI 0.4–4.4; P= 0.56). One of these cases was significantly unwell: she developed rhabdomyolysis following admission for diabetic ketoacidosis and then had a fatal haemorrhagic stroke. In addition, one participant admitted with a stroke which was complicated by an MI developed myopathy and died shortly afterwards.

The absolute risk of any myopathy (definite or incipient) among participants allocated study LDL-lowering therapy alone (i.e. the placebo group for the randomized comparison) was much higher in China than in Europe (0.13%/year vs. 0.04%/year; P = 0.001; Supplementary material online, Tables S4 and S5). In addition, the relative excess with allocation to ERN/LRPT was greater in China (RR 5.2; 95% CI 3.4–7.8) than in Europe (RR 1.5; 95% CI 0.7–3.3), and these risk ratios were significantly different from each other (interaction P-value = 0.008). As a consequence, the absolute excess of any myopathy associated with adding ERN/LRPT to statin-based LDL-lowering therapy was over 10 times greater among participants in China than among those in Europe (0.53%/year vs. 0.03%/year).

Discussion

HPS2-THRIVE is the largest ever randomized trial of ER niacin treatment and the present report provides uniquely reliable information about its tolerability and side-effect profile. About one-third of the potentially eligible individuals who started the 2-month ERN/LRPT run-in phase were excluded prior to randomization, with many reporting known side effects of niacin. Consequently, HPS2-THRIVE is assessing the clinical efficacy and safety of ERN/LRPT among the types of patient at high risk of vascular events who are likely to be able to take it long term, which is the relevant question in clinical practice.

Known side effects of niacin on the skin, gastrointestinal system and diabetes account for most of the excess of medical reasons given for stopping ERN/LRPT during both the pre-randomization run-in and post-randomization follow-up phases. Skin side effects account for about half the excess, with itching, rashes, and flushing all reported more frequently. Flushing has been a major cause of niacin intolerance18 but was less frequently reported than itching or rash in HPS2-THRIVE, perhaps due to laropiprant blocking prostaglandin D2 signalling (whereas itching and rash are mediated by prostaglandin E19). ERN/LRPT was also associated with an excess of indigestion and diarrhoea, but there was no apparent excess of hepatobiliary side effects.

A meta-analysis of niacin trials (predominantly among Caucasians not on a statin) did not find any evidence of an excess of muscle problems,12 and niacin is not thought to cause myopathy in the absence of statin therapy.20 However, during development of lovastatin, it was noted that the frequency of myopathy rose from 0.2% with lovastatin alone to 2% when co-administered with niacin.21 An important finding from the present analyses in HPS2-THRIVE is the highly significant four-fold excess risk of any myopathy with the addition of ERN/LRPT to simvastatin 40 mg daily (with or without ezetimibe 10 mg daily). This excess risk was particularly marked among the participants in China, where the background rate of myopathy with the study LDL-lowering therapy alone was higher than among the participants in Europe. During 2009, after definite myopathy had been recorded in 52 (including 34 after randomization) participants in China (and only 4 in Europe), the independent Data Monitoring Committee advised the investigators that it was substantially more frequent in the participants allocated active ERN/LRPT and the prescribing information was updated accordingly.22,23

The mechanism for this myopathy-related interaction between niacin and simvastatin is not clear. Nor is it clear why the rate of myopathy on simvastatin alone is higher among Chinese individuals. Niacin does not inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4 or interfere with statin-glucuronidation, but it has been found to increase simvastatin blood concentrations by about one-third,24 and statin-induced myopathy is known to be associated with higher blood statin levels.25 Asian subjects are also recognized to have higher blood levels than Caucasians following a given statin dose and this too may be a contributory factor.26 However, it should be noted that—even among Chinese individuals—this small absolute excess of myopathy with simvastatin 40 mg daily (with or without niacin) is likely to be greatly outweighed by its cardiovascular benefits in the sort of high-risk patients included in HPS2-THRIVE.1

Niacin has a variety of effects on lipids, including lowering LDL-C, apoB, and Lp(a) and raising HDL-C and apoA1, which might be expected to translate into reductions in vascular events. Over 25 000 people at high risk of vascular events were randomized in HPS2-THRIVE and three-quarters remained compliant with ERN/LRPT after 3.9 years' median follow-up. Based on this compliance and the lipid changes observed during the pre-randomization run-in, it was estimated prior to unblinding the trial that study average differences in LDL-C of ∼0.25 mmol/L and HDL-C of ∼0.13 mmol/L would have been achieved. Based on previous observational studies and randomized trials,1 it was anticipated that such lipid differences might translate into a 10–15% reduction in vascular events. At least 3400 of these high-risk participants were expected to have confirmed MVEs during an average of ∼4 years of follow-up, so HPS2-THRIVE has excellent statistical power to detect or exclude effects of this magnitude.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

HPS2-THRIVE was funded by a grant to Oxford University from Merck (manufacturers of ER niacin/laropiprant, ezetimibe and simvastatin), but the study was designed, and has been conducted, analysed and interpreted, independently by the Clinical Trial Service Unit & Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU) at the University of Oxford which is the regulatory sponsor for the trial. CTSU receives funding from the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation and Cancer Research UK. J.C.H. acknowledges support from the BHF Centre of Research Excellence, Oxford (RE/08/004).

Conflict of interest: The Clinical Trial Service Unit has a staff policy of not accepting honoraria or other payments from the pharmaceutical industry, except for the reimbursement of costs to participate in scientific meetings. L.J. and J.L. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The most important acknowledgement is to the participants in the study and to the collaborators listed in the appendix.

Appendix

Writing Committee: Richard Haynesa, Lixin Jianga, Jemma C Hopewell, Jing Li, Fang Chen, Sarah Parish, Martin J. Landray, Rory Collinsb and Jane Armitageb (ajoint first authors; bjoint senior authors).

Steering Committee: R. Collins (Chairman). Principal investigators: J. Armitage (Clinical Coordinator), C. Baigent, Z. Chen and M. Landray. Regional coordinators: Y. Chen and L. Jiang (China), T. Pedersen (Scandinavia), and M. Landray (UK). Other members: L. Bowman, F. Chen, M. Hill, R. Haynes, C. Knott, K. Rahimi, J. Tobert and P. Sleight. Lay member: D. Simpson. Statistician: S. Parish. Computing: A. Baxter and M. Lay. Administrative coordinators: C. Bray, E. Wincott. Merck representatives (non-voting): G. Leijenhorst (formerly A. Skattebol and G. Moen), Y. Mitchel and O. Kuznetsova.

Data Monitoring Committee: S. MacMahon (Chairman), J. Kjekshus, C. Hill, T.H. Lam and P. Sandercock. Statisticians (non-voting): R. Peto and J.C. Hopewell.

References

- 1.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, Albus C, Benlian P, Boysen G, Cifkova R, Deaton C, Ebrahim S, Fisher M, Germano G, Hobbs R, Hoes A, Karadeniz S, Mezzani A, Prescott E, Ryden L, Scherer M, Syvanne M, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Vrints C, Wood D, Zamorano JL, Zannad F. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–1701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, Kaptoge S, Ray KK, Thompson A, Wood AM, Lewington S, Sattar N, Packard CJ, Collins R, Thompson SG, Danesh J. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302:1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennet A, Di Angelantonio E, Erqou S, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Woodward M, Rumley A, Lowe GDO, Danesh J, Gudnason V. lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of future coronary heart disease: large-scale prospective data. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:598–608. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LA. Nicotinic acid: the broad-spectrum lipid drug. A 50th anniversary review. J Intern Med. 2005;258:94–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maccubbin D, Bays HE, Olsson AG, Elinoff V, Elis A, Mitchel Y, Sirah W, Betteridge A, Reyes R, Yu Q, Kuznetsova O, McCrary Sisk C, Pasternak RC, Paolini JF. Lipid-modifying efficacy and tolerability of extended-release niacin/laropiprant in patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. Int J Clin Practice. 2008;62:1959–1970. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, Parish S, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Rust S, Bennett D, Silveira A, Malarstig A, Green FR, Lathrop M, Gigante B, Leander K, de Faire U, Seedorf U, Hamsten A, Collins R, Watkins H, Farrall M. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bays HE, Maccubbin D, Meehan AG, Kuznetsova O, Mitchel YB, Paolini JF. Blood pressure-lowering effects of extended-release niacin alone and extended-release niacin/laropiprant combination: a post hoc analysis of a 24-week, placebo-controlled trial in dyslipidemic patients. Clin Ther. 2009;31:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy SM, Vega GL, McGovern ME, Tulloch BR, Kendall DM, Fitz-Patrick D, Ganda OP, Rosenson RS, Buse JB, Robertson DD, Sheehan JP. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of once-daily niacin for the treatment of dyslipidemia associated with type 2 diabetes: results of the assessment of diabetes control and evaluation of the efficacy of niaspan trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1568–1576. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W The AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birjmohun RS, Hutten BA, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Efficacy and safety of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol-increasing compounds: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maciejewski-Lenoir D, Richman JG, Hakak Y, Gaidarov I, Behan DP, Connolly DT. Langerhans cells release prostaglandin D2 in response to nicotinic acid. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2637–2646. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai E, De Lepeleire I, Crumley TM, Liu F, Wenning LA, Michiels N, Vets E, O'Neill G, Wagner JA, Gottesdiener K. Suppression of niacin-induced vasodilation with an antagonist to prostaglandin D2 receptor subtype 1. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:849–857. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SEARCH Collaborative Group. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy–a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:789–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang JM, Buring JE, Rosner B, Cook N, Hennekens CH. Estimating the effect of the run-in on the power of the Physicians' Health Study. Stat Med. 1991;10:1585–1593. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White SJ, Freedman LS. Allocation of patients to treatment groups in a controlled clinical study. Br J Cancer. 1978;37:849–857. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1978.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ER niacin (Niaspan): summary of product characteristics. 2008. 24 October 2012 http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Medicinesinformation/SPCandPILs/index.htm?prodName=NIASPAN%20500MG%20PROLONGED-RELEASE%20TABLETS&subsName=NICOTINIC%20ACID&pageID=SecondLevel. (15 February 2013)

- 19.Hanson J, Gille A, Zwykiel S, Lukasova M, Clausen BE, Ahmed K, Tunaru S, Wirth A, Offermanns S. Nicotinic acid- and monomethyl fumarate-induced flushing involves GPR109A expressed by keratinocytes and COX-2-dependent prostanoid formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2910–2919. doi: 10.1172/JCI42273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyton JR, Bays HE. Safety considerations with niacin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:S22–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobert JA. Efficacy and long-term adverse effect pattern of lovastatin. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:28J–34J. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ZOCOR (simvastatin) tablets prescribing information. 24 October 2012 http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/z/zocor/zocor_pi.pdf (12 February 2013)

- 23.Tredapative 1000 mg/20 mg modified release tablets SPC. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/22227/SPC/TREDAPTIVE+1000+mg+20+mg+modified+release+tablets/ (12 February 2013)

- 24.Kosoglou T, Zhu Y, Statkevich P, Triantafyllou I, Taggart W, Xuan F, Kim KT, Cutler DL. Assessment of potential pharmacokinetic interactions of ezetimibe/simvastatin and extended-release niacin tablets in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:483–492. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0955-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armitage J. The safety of statins in clinical practice. Lancet. 2007;370:1781–1790. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee E, Ryan S, Birmingham B, Zalikowski J, March R, Ambrose H, Moore R, Lee C, Chen Y, Schneck D. Rosuvastatin pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics in white and Asian subjects residing in the same environment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.