Abstract

Modifications on histones or on DNA recruit proteins that regulate chromatin function. Here we use nucleosomes methylated on DNA and on histone H3 in an affinity assay, in conjunction with a SILAC-based proteomic analysis, to identify “cross-talk” between these two distinct classes of modification. Our analysis reveals proteins whose binding to nucleosomes is regulated by methylation of CpGs, H3K4, H3K9, and H3K27 or a combination thereof. We identify the Origin Recognition Complex (ORC), including LRWD1 as a subunit, to be a methylation-sensitive nucleosome interactor which is recruited cooperatively by DNA and histone methylation. Other interactors, such as the lysine demethylase Fbxl11/KDM2A, recognise nucleosomes methylated on histones but their recruitment is disrupted by DNA methylation. These data establish SILAC nucleosome affinity purifications (SNAP) as a tool for studying the dynamics between different chromatin modifications and provide a modification binding “profile” for proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation.

Introduction

Most of the genetic information of eukaryotic cells is stored in the nucleus in the form of a nucleoprotein complex termed chromatin. The basic unit of chromatin is the nucleosome which consists of 147 bp of DNA wrapped around an octamer made up of two copies each of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 (Luger et al., 1997). Nucleosomes are arranged into higher order structures by additional proteins, including the linker histone H1, to form chromatin. Since chromatin serves as the primary substrate for all DNA-related processes in the nucleus its structure and activity must be tightly controlled.

Two key mechanisms known to regulate the functional state of chromatin in higher eukaryotes are the C5-methylation of DNA at cytosines within CpG dinucleotides and the post-translational modification of amino acids of histone proteins. Whereas DNA methylation is usually linked to silent chromatin and is present in most regions of the genome (Bernstein et al., 2007), the repertoire and the location of histone modifications is much more diverse with different modifications associated with different biological functions (Kouzarides, 2007). Most modifications can also be removed from chromatin, thus conferring flexibility in the regulation of its activity. Due to the large number of possible modifications and the enormous diversity that can be generated through combinatorial modifications, epigenetic information can be stored in chromatin modification patterns. Several chromatin-regulating factors have recently been identified that recognise methylated DNA or modified histone proteins. Such effector molecules use a range of different recognition domains such as methyl-CpG-binding domains (MBD), zinc fingers (ZnF), chromo-domains, or plant homeodomains (PHD) in order to establish and orchestrate biological events (Sasai and Defossez, 2009; Taverna et al., 2007). However, most of these studies were conducted using isolated DNA or histone peptides and cannot recapitulate the situation found in chromatin. Considering the three-dimensional organisation of chromatin in the nucleus, DNA methylation and histone modifications most likely act in a concerted manner by creating a “modification landscape” that must be interpreted by proteins able to recognise large molecular assemblies (Ruthenburg et al., 2007).

In an effort to increase our understanding of how combinatorial modifications on chromatin might modulate its activity, we set out to identify factors that recognise methylated DNA and histones in the context of nucleosomes. We reasoned that using whole nucleosomes would enable us to find factors that integrate the folded nucleosomal structure with modifications on the DNA and on histones. Here we describe a SILAC nucleosome affinity purification (SNAP) approach for the identification of proteins that are influenced by CpG-methylation and histone H3 K4, K9 or K27 methylation (or a combination thereof) in the context of a nucleosome. Our results reveal many proteins and complexes that can read the chromatin modification status. These results establish SNAP as a valuable approach in defining the chromatin “interactome”.

Results

The SILAC Nucleosome Affinity Purification (SNAP)

Proteins recognise modifications of chromatin in the context of a nucleosome. However, to date modification-interacting proteins have been identified using modified DNA or modified histone peptides as affinity columns. We set out to identify proteins that can sense the presence of DNA and histone methylation within the physiological background of a nucleosome. To this end we reconstituted recombinant nucleosomes containing combinations of CpG methylated DNA and histone H3 tri-methylated at lysine residues 4, 9, and 27 (H3K4me3, H3K9me3 or H3K27me3). These modified nucleosomes were immobilised on beads and used to affinity purify interacting proteins from SILAC-labelled HeLa nuclear extracts (Figure 1A). Bound proteins regulated by the different modification patterns were identified by mass spectrometry (MS).

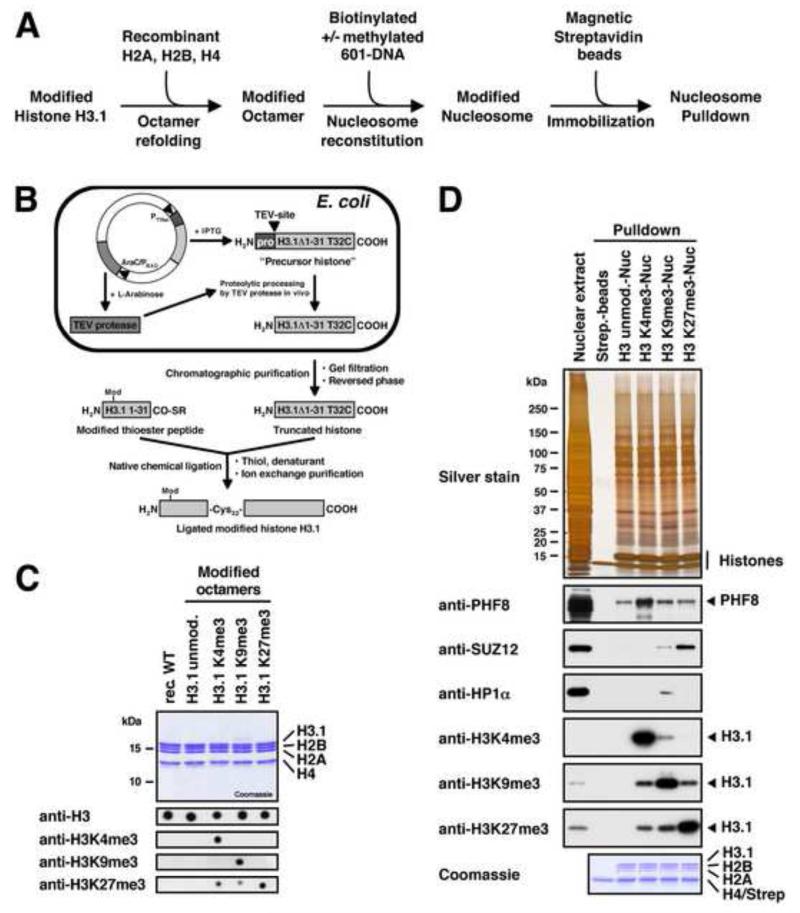

Figure 1. Preparation of Reconstituted Modified Nucleosomes.

(A) Experimental strategy for the preparation of immobilised and modified nucleosomes for pulldown studies. (B) The native chemical ligation strategy for generating post-translationally modified histone H3.1. We bacterially express an IPTG-inducible truncated histone precursor containing a modified TEV-cleavage site (ENLYFQ↓C) followed by the core sequence of histone H3.1 starting from glycine 33. The plasmid also contains TEV-protease under the control of the AraC/PBAD-promoter. TEV-protease accepts a cysteine instead of glycine or serine as the P1′-residue of its recognition site, and upon arabinose induction it processes the precursor histone into the truncated form (H3.1Δ1-31 T32C) which is purified and ligated to modified thioester peptides spanning the N-terminal residues 1 to 31 of histone H3.1. All ligated histones contain the desired modification and a T32C mutation. (C) Summary of the modified histone octamers. The upper panel shows 1 μg of each octamer separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie. For the bottom panel octamers were dot blotted on PVDF-membranes and probed with modification-specific antibodies as indicated. The anti-H3K27me3 antibody shows slight cross-reactivity with H3K4me3 and H3K9me3. (D) Functional test of the nucleosome affinity matrix. R10K8-labelled nuclear extract was incubated with immobilised modified nucleosomes as indicated. Binding of PHF8, HP1α, and SUZ12 was detected by immunoblot. Equal loading was confirmed by silver and Coomassie staining. Modification of histone H3 was verified by immunoblot against H3 tri-methyl lysine marks. All three antibodies show slight cross-reactivity with the other histone marks. See also Figure S1.

The methylation of lysines in H3 was accomplished by native chemical ligation (Muir, 2003). An existing protocol (Shogren-Knaak et al., 2003) was adapted to develop an improved method that allows the purification of large quantities of recombinant tail-less human H3.1 (Figure 1B). This method employs the co-expression of Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV)-protease and a modified TEV-cleavage site (Tolbert and Wong, 2002) to expose a cysteine in front of the histone core sequence in E. coli (Figure S1A). The tail-less H3.1 starting with a cysteine at position 32 was ligated to thioester peptides spanning the N-terminus of histone H3.1 (residues 1-31) and containing the above-mentioned methylated lysines (Figure S1B). The resulting full length modified H3.1 proteins (Figure S1C) were subsequently refolded into histone octamers together with recombinant human histones H2A, H2B, and H4 (Figure 1C).

As nucleosomal DNAs we used two biotinylated 185 bp DNA-fragments containing either the 601- or the 603-nucleosome positioning sequences (Lowary and Widom, 1998). Both DNAs have similar nucleosome-forming properties albeit with different sequences (Figure S1D) which allows us to test for sequence specificities of methyl-CpG interactors. The nucleosomal DNAs were treated with recombinant prokaryotic M.SssI DNA methyltransferase which mimics the methylation pattern found at CpG dinucleotides in eukaryotic genomic DNA (Figures S1E and S1F). Finally, nucleosomal core particles were reconstituted from the nucleosomal DNAs and octamers and immobilised on streptavidin beads via the biotinylated DNAs. All assembly reactions were quality controlled on native PAGE gels (Figure S1G).

The immobilised modified nucleosomes were incubated in HeLaS3 nuclear extracts and probed for the binding of known modification-interacting factors to make sure that the nucleosomal templates were functional. Figure 1D shows that, as expected, PHF8, HP1α and the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) subunit SUZ12 (Bannister et al., 2001; Hansen et al., 2008; Kleine-Kohlbrecher et al., 2010) specifically bind to H3K4me3-, H3K9me3-, and H3K27me3-modified nucleosomes, respectively. In addition, we did not detect any modification of the immobilised nucleosomal histones by modifying activities present in the nuclear extract (Figure S1H).

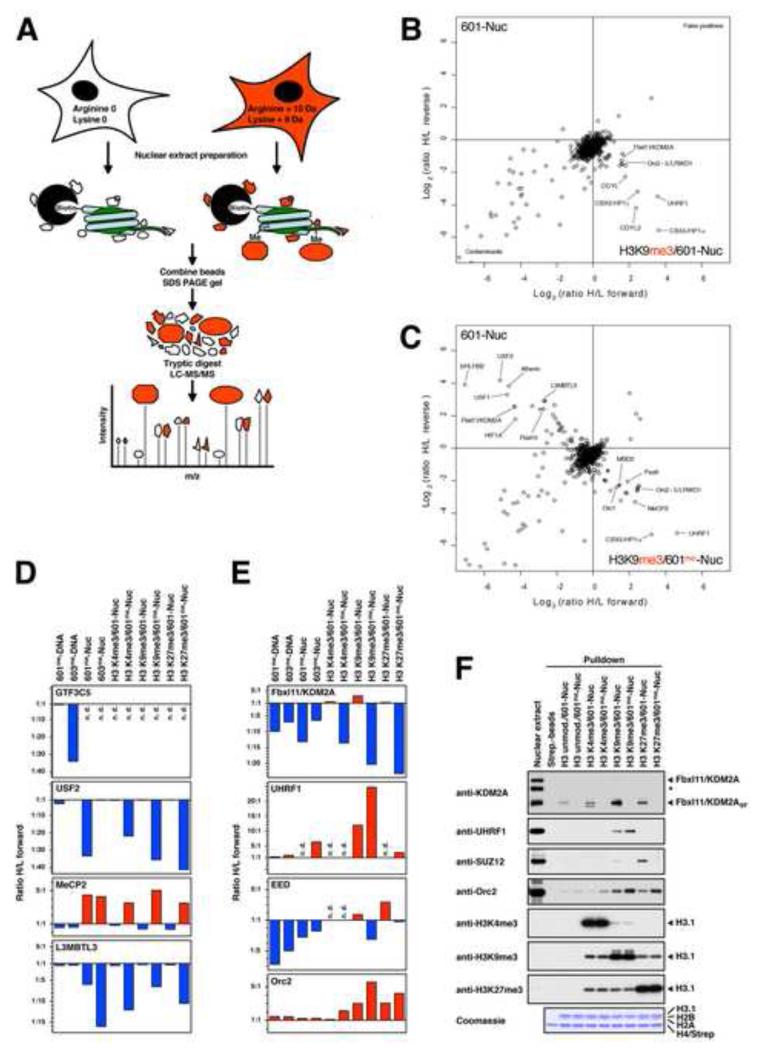

In order to identify proteins that bind to chromatin in a modification-dependent manner we utilised a SILAC pulldown approach that we have developed to identify interactors of histone modifications (Vermeulen et al., 2010). We simply replaced immobilised peptides with complete reconstituted modified nucleosomes (Figure 2A). All pulldowns were repeated in two experiments. In a “forward” experiment the unmodified nucleosomes were incubated with light (R0K0) extracts and the modified nucleosomes were incubated with heavy-labelled (R10K8) extracts, as depicted in Figure 2A. In an independent “reverse” experiment the extracts were exchanged. Bound proteins were identified and quantified by high resolution MS for both pulldown experiments. A logarithmic (Log2) plot of the SILAC ratios H/L of the forward (X-axis) and reverse (Y-axis) experiments for each identified protein allows the unbiased identification of proteins that specifically bind to the modified or the unmodified nucleosomes. Proteins that preferentially bind to the modified nucleosomes show a high ratio H/L in the forward and a low ratio H/L in the reverse experiment and can, therefore, be identified as outliers in the bottom right quadrant. Proteins that are excluded by the modification have a low ratio H/L in the forward experiment and a high ratio H/L in the reverse experiment and appear in the top left quadrant. Background binders have a ratio H/L of around 1:1 and cluster around the intersection of the X- and Y-axes. Outliers in the bottom left quadrant are contaminating proteins. Outliers in the top right quadrant are false positives. An enrichment/exclusion ratio of 1.5 in both directions generally identifies outliers outside of the background cluster. We consider a protein to be significantly regulated when it is enriched/excluded at least 2-fold. Higher ratios H/L in the forward and lower ratios H/L in the reverse experiments indicate stronger binding whereas stronger exclusion is indicated by lower ratios H/L in the forward and higher ratios H/L in the reverse experiments.

Figure 2. Identification of Nucleosome-interacting Proteins Regulated by DNA and Histone Methylation using SNAP.

(A) Experimental design of the SILAC nucleosome affinity purifications. Nuclear extracts are prepared from HeLaS3 cells grown in conventional “light” medium or medium containing stable isotope-labelled “heavy” amino acids. The resulting “light”- and “heavy”-labelled proteins can be distinguished and quantified by MS. Immobilised unmodified or modified nucleosomes are separately incubated with light or heavy extracts, respectively. Both pulldown reactions are pooled and eluted proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE. After in-gel trypsin digestion, peptides are analysed by high resolution MS. (B) Results of SNAP performed with H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes containing unmethylated 601-DNA. Shown are the Log2-values of the SILAC ratios (ratio H/L) of each identified protein for the forward (X-axis) and the reverse (Y-axis) experiments. The identities of several interacting proteins are indicated. Subunits of the MBD2/NuRD-complex are labelled in orange. (C) Results of SNAP performed with H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes containing CpG-methylated 601-DNA. For additional SNAP results see Figure S2 and Table S1. (D) Differential recognition of nucleosomes. The graphs show the forward SILAC enrichment values (Ratio H/L forward) of MeCP2, L3MBTL3, USF2, and the TFIIIC subunit GTF3C5 on CpG-methylated DNAs and modified nucleosomes. Binding to the modified nucleosomes or DNAs is indicated in red, exclusion is indicated in blue. If proteins were not detected (n.d.) no value is assigned. (E) Crosstalk between DNA and histone methylation. The graphs show the SILAC enrichment values of the proteins KDM2A, UHRF1, the PRC2 subunit EED, and the ORC subunit Orc2 as described in (D). (F) Immobilised modified nucleosomes were incubated with an independently prepared R0K0-nuclear extract as indicated. Binding of KDM2A, UHRF1, Orc2, and the PRC2 subunit SUZ12 was detected by immunoblot. Equal loading and modification of histone H3 were verified as in Figure 1D. The asterisk marks a cross-reactive band recognised by the KDM2A antibody.

Proteins Identified by SNAP

The SNAP approach was used to identify proteins that are recruited or excluded by DNA methylation, histone H3 methylation, or a combination of both (Figures 2B, 2C and S2). In Tables 1, 2 and Table S2 we summarise the proteins that display a regulation of at least 1.5 in both, the forward and reverse experiments, thus defining the proteins that are enriched or excluded by the modified nucleosomes. The complete MS analysis defining all interacting proteins in all pulldown reactions is summarised in Table S1.

Table 1.

Proteins Enriched or Excluded by CpG-methylated DNA and Nucleosomes as Identified by SNAP

| Enrichment/Exclusion (Ratio H/L forward) |

601me-DNA | 603me-DNA | 601me-Nuc | 603me-Nuc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched Proteins | Very Strong Enrichment (>10) |

ZBTB33 | ZBTB33 | ZHX2 | |

| Strong Enrichment (5 - 10) |

ZHX1 | ZHX1 MBD22 HOMEZ |

UHRF1 | ||

| Moderate Enrichment (2 - 5) |

ZBTB9 ZHX2 ZHX3 MBD22 MTA22 CDK2AP12 GATAD2A2 FOXA1 CHD42 ZNF295 MTA32 HOMEZ MTA12 GATAD2B2 MBD4 |

ZHX2 MTA22 GATAD2A2 MTA32 ZHX3 CDK2AP12 FOXA1 CHD42 GATAD2B2 RFXANK4 RFXAP4 MTA12 PBX1 RFX54 PKNOX1 FIZ1 TRIM28 ZBTB40 |

MeCP2 PAX6 MTERF MBD22 |

GATAD2A2 MTA22 MBD22 MBD4 ZBTB12 CHD42 MeCP2 GATAD2B2 ZHX3 ZHX1 C14orf93 RBBP42 RBBP72 MTERF PAX6 LCOR |

|

| Weak Enrichment (1.5 - 2) |

PAX9 CHD32 CUX1 ZNF740* |

RBBP72 POGZ KIAA1958 UHRF1 ZNF787 MBD4 CHD32 ZFHX3 ZBTB9* NR2C1 MAD2B |

MTA22 MBD4 CHD42 GATAD2A2 PPIB |

ACTR5 ZBED5 AURKA HOXC10 JUNB |

|

| Excluded Proteins | Weak Exclusion (0.5 - 0.67) |

ANKRD32 | Atherin* SKP1*,1 RBBP5 NUFIP1 CBFB |

MSH3 RBBP5 |

|

| Moderate Exclusion (0.2 - 0.5) |

RB1 TFEB SIX4 HES7 ZFP161 YAF2 TIGD5 ARID4B CXXC5 SKP11 JRK USF2 USF1 FBXW11 RAD1 ZBTB2 MLX BCORL1 ZNF639 |

SP3 HES7 TCOF1* TFDP1 ATF1 MLL SKP11 RECQL ONECUT2 ZFP161 TIGD1 RB1 E2F3 CUX1 EED3 |

RUNX RNF21 RING11 BANP PRDM11 SUZ123 NAIF1 MYC SUB1 |

RMI1 TOP3A RPA25 NAIF1 RPA15 RPA35 KIAA1553 TCF7L2 RNF21 BCOR1 RING11 BANP* |

|

| Strong Exclusion (0.1 - 0.2) |

ZBTB25 PURB RPA15 RPA3*,5 RPA25 MNT UBF1 UBF2 EED3 SUZ123 VHL E2F4 BCOR1 FBXL101 FBXL11 |

SUZ123 RPA35 SSBP1 RPA25 RPA15 CGGBP1 UBF2 FBXL11 PURA UBF1 ZBTB2 ZNF639 RAD1 HUS1 PURB BCORL1 OLA1 |

MAX L3MBTL3 BCOR1 FBXL101 PCGF11 |

FBXL11 SUB1 FBXL101 |

|

| Very Strong Exclusion (< 0.1) |

E2F1 PCGF11 ZNF395 TIMM8A KIAA1553 bHLHB2 CGGBP1 GMEB2 |

GTF3C26 BCOR1 GTF3C46 FBXL101 PCGF11 GTF3C16 E2F1 DEAF1 GTF3C36 GTF3C66 GTF3C56 |

HIF1A CXXC5 BCORL1* FBXL11 Syntenin1 ARNT HES7 USF2 bHLHB2 USF1 |

PCGF11 Atherin L3MBTL3 FLYWCH1 Syntenin1 ZFP161 |

|

Table 1 shows the proteins that were enriched or excluded by CpG-methylated DNA or nucleosomes compared to the respective unmodified species at least 1.5-fold in both, the forward and reverse pulldown experiments. Proteins are grouped according to their ratio H/L in the forward experiments. Proteins marked by an asterisk are just below the threshold. For the values of the SILAC ratios see Tables S1 and S2. Protein complex subunits:

BCOR-complex,

NuRD-complex,

PRC2-complex,

Regulatory factor X,

Replication factor A-complex,

TFIIIC-complex.

Table 2.

Nucleosome-binding Proteins Regulated by CpG- and Lysine-Methylation as Identified by SNAP

| Enrichment/Exclusion (Ratio H/L forward) |

H3K4me3/ 601-Nuc |

H3K4me3/ 601me-Nuc |

H3K9me3/ 601-Nuc |

H3K9me3/ 601me-Nuc |

H3K27me3/ 601-Nuc |

H3K27me3/ 601me-Nuc |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched Proteins | Very Strong Enrichment (>10) |

Spindlin1 | IWS1# Spindlin1 |

CBX5/HP1α UHRF1 |

UHRF1 | ||

| Strong Enrichment (5 - 10) |

PHF8 CHD1 |

PHF8 | CBX3/HP1γ CDYL2 |

CBX5/HP1α Orc43 Orc23 Orc33 Orc53 LRWD1 MeCP2 |

|||

| Moderate Enrichment (2 - 5) |

DIDO1 UBF1 Sin3A6 |

PAX6 CHD1 MeCP2 MTERF MBD22 DIDO1 Orc23 Orc43 MBD4 |

LRWD1 CDYL FBXL11 UBF1 Orc23 Orc43 Orc53 Orc33 |

PAX6 CBX3/HP1γ CDYL MTERF MBD22 Orc13 |

C17orf96 LRWD1 EED4 Orc43 Orc53 SUZ124 Orc23 Orc33 EZH24 MTF2 CBX8 |

LRWD1 Orc23 Orc33 Orc43 Orc53 MeCP2 CBX8 UHRF1 PAX6 MTERF Orc13 |

|

| Weak Enrichment (1.5 - 2) |

SAP306 WDR82 EMG1 TAF9B PPIB VRK2 HNRNPA1* HNRNPA2B1* ING4 WDR61 HNRNPA0* FLYWCH1 BUB3 FUBP3 |

Orc53 LRWD1 PPIB ING4 TOX4 MTA22 CHD42 ZSCAN21 Orc33 NONO CDCA7L* WDR82* |

CHD1 SUZ124 EED4 PPIB NONO MTF2 SUB1 |

MTA22 MBD4 ZSCAN21 CHD42 NSD3 |

PPIB | CDCA7L BMI1 PPIB MTA22 MBD4* |

|

| Excluded Proteins | Weak Exclusion (0.5 - 0.67) |

SKP11 RCOR1 |

SKP11 CREB1 |

HCFC1 PHF14 SKP11 |

|||

| Moderate Exclusion (0.2 - 0.5) |

HMG20A HMG20B MTF2* |

RING11 SUB1 HMG20B NAIF MYC |

IMP4 | RCOR1 BANP RING11 SUB1 EED4 TIGD5 RNF21 MYC NAIF1 ARNT TCF7L2 HES7 |

SPTH167 SSRP17 TCF7L2 BANP* PRDM11 NAIF1 RPA15 BANP* SUB1 |

||

| Strong Exclusion (0.1 - 0.2) |

PHF14 | FBXL101 PHF14 BCOR1 PCGF11 |

MAX CXXC5 L3MBTL3 FBXL101 BCOR1 |

RPA25 BCOR1 MYC FBXL101 PCGF11 MAX |

|||

| Very Strong Exclusion (< 0.1) |

L3MBTL3 ARNT FBXL11 Syntenin1 Atherin USF2 USF1 HIF1A* bHLHB2 |

PCGF11 HIF1A Syntenin1 FBXL11 Atherin USF1 USF2 bHLHB2 |

L3MBTL3 HES7 Syntenin1 HIF1A Atherin ARNT FBXL11 USF1 USF2 bHLHB2 |

||||

Table 2 shows the proteins that were enriched or excluded by modified nucleosomes compared to unmodified nucleosomes at least 1.5-fold in both, the forward and reverse pulldown experiments. Proteins are grouped according to their ratio H/L in the forward experiments. Proteins marked by an asterisk are just below the threshold. For the values of the SILAC ratios see Tables S1 and S2. Protein complex subunits:

BCOR-complex,

NuRD-complex,

ORC complex,

PRC2-complex,

Replication factor A-complex,

Sin3A-complex,

FACT.

IWS should be treated with caution since it was found as a false positive outlier in the 601me-Nuc pulldown. Fbxl11/KDM2A is highlighted in bold.

The dataset includes a number of proteins (about 20%) that are already known to bind methyl-DNA and methyl-H3 as well as many proteins whose regulation by modifications had not been previously defined. The presence of many known methyl-binding proteins validates our approach. The database provides a complex “profile” for the modulation of proteins by DNA and histone methylation that have the potential to recognise specific “chromatin landscapes”. Below we highlight several interactions with modified nucleosomes which exemplify the different modes of regulation we observe (summarised in Figure 2D and E).

Regulation by CpG Methylation

Table 1 shows DNA- and nucleosome-binding proteins regulated by CpG methylation. The two different methylated DNAs were subjected to SNAP analysis either on their own (601me-DNA and 603me-DNA) or assembled into nucleosomes (601me-Nuc and 603me-Nuc). We identify several well characterised methyl-binding proteins such as MBD2 (Sasai and Defossez, 2009) to be enriched on the 601me- and 603me-DNAs. MBD2 is enriched on both DNAs and exemplifies a form of methyl-CpG binding that is not sequence selective. In contrast, other proteins (e.g. ZNF295) display sequence specificity towards only one of the methylated DNAs, suggesting that they may recognise CpG methylation in a sequence specific manner.

We also identify many proteins that preferentially recognise non-methylated DNA and are excluded by CpG-methylation. The most prominent example is the general RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIC. All subunits of the TFIIIC complex show specific exclusion from the 603me-DNA (e.g. GTF3C5 shown in Figure 2D) most likely because this DNA (unlike the 601me-DNA) contains two putative B-box elements (Figure S1D), sequences which are known TFIIIC binding sites. This defines a form of methyl-CpG-dependent exclusion that is sequence specific.

CpG-methylation can have a distinct influence on protein binding when it is present within a nucleosomal background. Factors such as MeCP2 are specifically enriched on CpG-methylated DNA only in the context of a nucleosome but not on free DNA (Figure 2D). Other factors, such as L3MBTL3, show nucleosome-dependent exclusion by CpG methylation. These two factors are influenced by DNA methylation regardless of DNA sequence. Several proteins, such as the DNA binding factor USF2 are specifically excluded only from 601me-nucleosomes. This is most likely due to an E-box motif in the 601-DNA (Figure S1D) which is recognised by USF2.

One final example of the effect of nucleosomes on DNA binding proteins is demonstrated by the observation that many proteins such as TFIIIC bind free DNA but cannot recognise the DNA when it is assembled into nucleosomes. This is probably due to binding motifs (such as the B-box motif) being occluded by the histone octamer (Figure 2D and Table S2). This type of interaction may identify proteins that need nucleosome remodelling activities to bind their DNA element. Together these examples highlight the additional constraints forced on protein-DNA interactions by the histone octamer.

Regulation by H3 Lysine Methylation

Table 2 shows a summary of the proteins enriched or excluded by nucleosomes tri-methylated at H3K4, H3K9 or H3K27 in the presence or absence of DNA methylation. Tri-methylation of H3K4 is primarily associated with active promoters whereas tri-methyl H3K9 and H3K27 as well as methyl-CpG are hallmarks of silenced regions of the genome (Kouzarides, 2007).

We identify several known histone methyl-binding proteins in our screen such as the H3K4me3-interactor CHD1, the H3K9me3-binder UHRF1 and the H3K27me3-interacting polycomb group protein CBX8 (Hansen et al., 2008; Karagianni et al., 2008; Pray-Grant et al., 2005). In addition, a number of uncharacterised factors were identified. For example Spindlin1 binds strongly to H3K4me3. Spindlin1 is a highly conserved protein consisting of three Spin/Ssty domains that have recently been shown to fold into Tudor-like domains (Zhao et al., 2007), motifs known to bind methyl-lysines on histone proteins. Most notably, we identify the origin recognition complex (Orc2, Orc3, Orc4, Orc5, and to a lesser extent Orc1) to be enriched on both, H3K9me3- and H3K27me3-modified nucleosomes. Since no binding was detected on H3K4me3-nucleosomes, the origin recognition complex (ORC) seems to specifically recognise heterochromatic modifications (Figure 2E). One protein, PHF14, and to a lesser extent HMG20A and HMG20B, are excluded by the H3K4me3-modification. Interestingly, these factors represent the only significant examples of proteins excluded from nucleosomes by methylation of histones, including methylation at H3K9 and H3K27.

Crosstalk Between DNA and Histone Methylation

The SNAP approach allows us to investigate cooperative effects between DNA methylation and histone modifications on the recruitment of proteins to chromatin. Analysis of our data reveals several examples of such a regulation (Figures 2E and 2F). We observe a cooperative stronger binding of UHRF1 to H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes in the presence of CpG-methylation. Similarly, the ORC complex (as shown for the Orc2 subunit) can recognise nucleosomes more effectively if CpG-methylation coincides with the repressive histone marks H3K9me3 or H3K27me3. This might explain its preferential localisation to heterochromatic regions in the nucleus (Pak et al., 1997; Prasanth et al., 2004). In contrast, the H3K36 demethylase Fbxl11/KDM2A is enriched by H3K9-methylation but excluded by DNA methylation. Finally, the PRC2 complex is enriched on H3K27me3-nucleosomes (and to a lesser extent on H3K9me3-nucleosomes) but incorporation of methyl-CpG DNA counteracts this recruitment as shown for the EED (Figure 2E) and the SUZ12 (Figure 2F) subunits. These findings demonstrate the ability of these factors to simultaneously monitor the methylation status of both histones and DNA on a single nucleosome.

Identification of Complexes Regulated by Chromatin Modifications

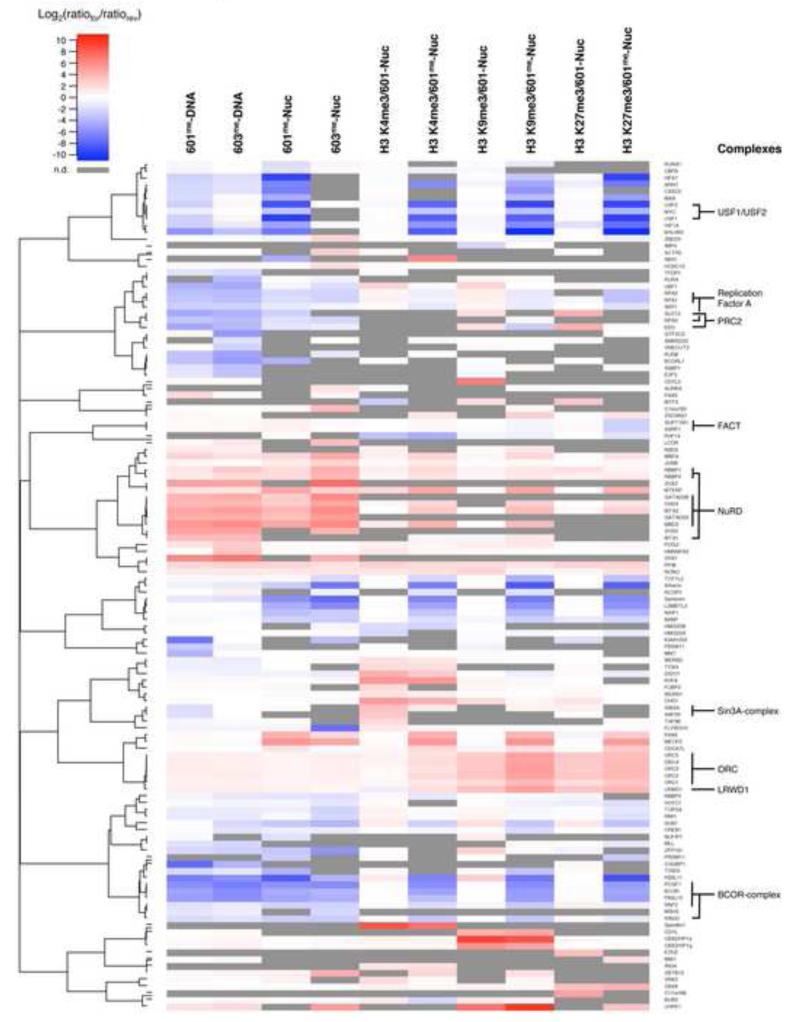

The proteins regulated by nucleosome modifications in the SNAP experiments were subjected to a cluster analysis in order to define common features of regulation. In this analysis the SILAC enrichment values are represented as a heat map in which proteins with similar interaction profiles group into clusters that may be indicative of protein complexes. Figure 3 shows that members of several known complexes cluster together in this analysis, including the BCOR and the NuRD corepressor complexes (Gearhart et al., 2006; Le Guezennec et al., 2006).

Figure 3. Interaction Profiles of Chromatin Modification-binding Proteins.

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering was performed on the SILAC enrichment values of proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation to identify proteins with related binding profiles. This analysis includes proteins based on an enrichment/exclusion of at least 1.5 fold in both directions in one of the nucleosome pulldown experiments and excludes factors that were found solely in the DNA pulldowns. Log2(ratiofor/ratiorev) is the log2 ratio between the SILAC values (ratio H/L) of the forward and reverse experiments. Enrichment by modifications is indicated in red, exclusion is indicated in blue. Grey bars indicate if proteins were not detected (n.d.) in particular experiments. These incidences were not included in the cluster analysis. Clusters of several known protein complexes and their respective subunits are indicated on the right. For values see Table S2.

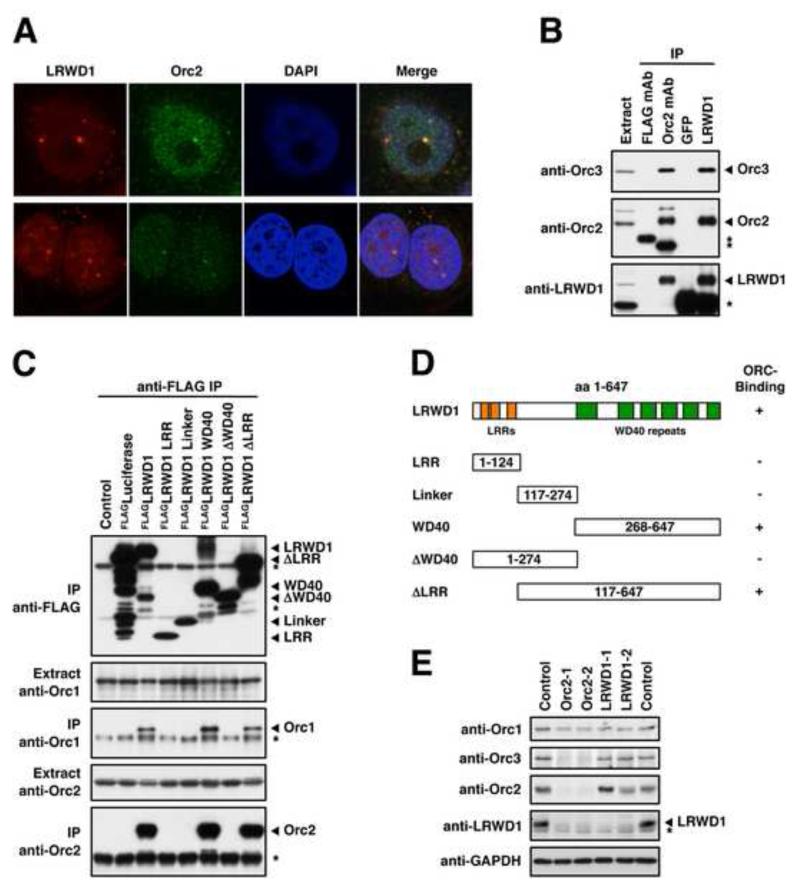

Identification of LRWD1 as an ORC-interacting Protein

The cluster analysis also identifies the ORC complex based on the similar interaction profiles of the ORC subunits. Interestingly an uncharacterised protein termed LRWD1 closely associates with the ORC cluster (see also Figures 2B, C and S2G, H) suggesting that this protein may be a component of ORC. To test this hypothesis we raised an antibody against LRWD1 (Figure S3A) and used it to probe for co-localisation with the ORC complex by immunofluorescence (IF) staining of MCF7 cells. Figure 4A indicates that LRWD1 co-localises with the ORC complex at a subset of nuclear foci marked by strong staining with an antibody against the Orc2 subunit. As previously shown for Orc2 (Prasanth et al., 2004), these foci often co-localise with HP1α, a marker for H3K9me3-containing heterochromatin (Figure S3B). In addition, endogenous LRWD1 and Orc2 can be co-immunoprecipitated from extracts prepared from MCF7 and HelaS3 cells (Figures 4B and S3C). We further expressed various truncated variants of FLAG-tagged LRWD1 in 293T cells and immunoprecipitated them using an anti-FLAG antibody. The co-immunoprecipitation of Orc1 and Orc2 indicates that LRWD1 interacts with ORC via its WD40 domain (Figures 4C and D and S3D). Similar to Orc3 (Prasanth et al., 2004), expression of LRWD1 depends on Orc2 since reducing Orc2 expression in MCF7 cells by siRNA treatment also reduces LRWD1 protein levels (Figure 4E) without perturbing its transcription (data not shown). These experiments establish LRWD1 as an ORC-component and demonstrate the potential of the modification interaction profiling for the identification of protein complex subunits.

Figure 4. LRWD1 Interacts with the Origin Recognition Complex.

(A) LRWD1 co-localises with Orc2. IF staining of MCF7 cells with LWRD1 (2527) and Orc2 antibodies following pre-extraction shows co-localisation at distinct nuclear foci. (B) LRWD1 and ORC co-immunoprecipitate. LRWD1 and Orc2 were immunoprecipitated from MCF7 whole cell extracts and interacting proteins were detected by immunoblot as indicated. LRWD1 was immunoprecipitated using anti-LRWD1 (A301-867A) and detected using anti-LRWD1 (2527) antibodies. Anti-FLAG and anti-GFP antibodies were used as IgG negative controls. Asterisks mark bands derived from antibody heavy chains. (C) FLAG-tagged full length and truncated versions of LRWD1 were over-expressed in 293T cells and immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. 1 % of the input and 10% of the IP were separated by SDS-PAGE and Orc1, Orc2 and the FLAG fusions were detected by immunoblot. The asterisks mark bands derived from the anti-FLAG IP antibody. (D) Identities of the LRWD1 truncation constructs. Only deletions containing the WD40 repeats interact with ORC. (E) LRWD1 expression is Orc2-dependent. Expression levels of LRWD1 and ORC proteins in MCF7 cells were detected by immunoblot after transfection with siRNAs against LRWD1 and Orc2 as indicated. Cells were reverse-transfected twice, 56 h and 28h before harvesting. GAPDH serves as a loading control. The asterisk marks a cross-reactive band detected by the anti-LRWD1 (2527) antibody. See also Figure S3.

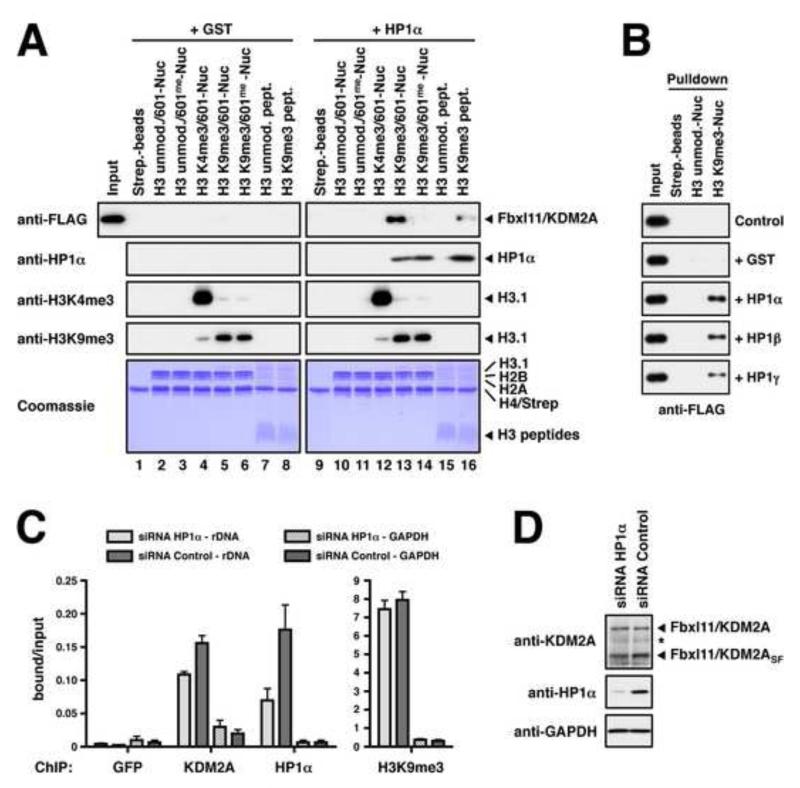

Recognition of Nucleosome Modification Status by Fbxl11/KDM2A

To provide independent validation of the SNAP approach we investigated in more detail the modulation of binding of Fbxl11/KDM2A by DNA and histone methylation. This enzyme is a JmjC-domain protein that demethylates lysine 36 on histone H3 (Tsukada et al., 2006). Our data show that KDM2A is enriched on H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes but its recruitment is disrupted by CpG-methylation on either free or nucleosomal DNA (Figure 2E).

KDM2A has several described isoforms and in our initial SNAP experiments some identified KDM2A peptides showed a markedly lower enrichment than others. The H3K9me3-nucleosome SILAC pulldown was repeated to assign the identified peptides to gel bands covering different molecular weights. Most peptides were detected in a band corresponding to a molecular weight of 60-75 kDa and mapped to the C-terminal half of KDM2A (Figure S4A and B). Probing for the binding of KDM2A to modified nucleosomes by immunoblot also showed enrichment of a lower molecular weight isoform (Figures 2F and S4C). Immunoprecipitating KDM2A from nuclear extracts confirmed the presence of this isoform (Figure S4D). This variant corresponds to the recently described 70 kDa isoform KDM2ASF that is transcribed from an alternative promoter and spans the C-terminal half of KDM2A from position 543 (Tanaka et al., 2010).

We next sought to verify the recruitment of KDM2A to the H3K9me3-modification seen by SNAP in a different biochemical assay. To this end, various methylated and unmethylated nucleosomes or histone H3 peptides were used to isolate FLAG-tagged full length KDM2A from transfected 293T cell extracts. The SILAC experiments indicated a moderate enrichment of KDM2A on H3K9me3-nucleosomes (Figure 2E). However, we could not detect substantial binding to either H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes (Figure 5A, lane 5) or peptides (Figure 5A, lane 8) with the over-expressed protein. This result suggested the possibility that KDM2A may need a second factor in order to recognise H3K9me3. A recent study reporting the interaction of KDM2A with all HP1 isoforms (Frescas et al., 2008) prompted us to test whether the binding was mediated by HP1. Indeed, addition of purified HP1α to the pulldown reactions strongly stimulated the association of KDM2A to H3K9me3-nucleosomes (Figure 5A, lane 13). Using HP1α, β, and γ showed that the interaction could be mediated by all HP1 isoforms (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Fbxl11/KDM2A Integrates DNA Methylation and H3K9me3-modification Signals on Nucleosomes.

(A) In vitro binding of KDM2A to modified nucleosomes. Whole cell extracts prepared from transiently transfected 293T cells over-expressing FLAG-tagged KDM2A were incubated with immobilised modified nucleosomes or modified H3-peptides as indicated. Binding reactions were supplemented with recombinant purified HP1α or GST as a control. Binding was detected by immunoblot against the FLAG-tag or HP1α. Equal loading of the nucleosomes and peptides, and modification of histone H3 were verified as in Figure 1D. (B) KDM2A binding to H3K9me3-Nucleosomes is mediated by HP1α, β, and γ. Unmodified or H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes were immobilised on streptavidin beads and incubated with 293T whole cell extracts over-expressing FLAG-tagged KDM2A. Pulldown reactions were supplemented with recombinant purified HP1α, β, or γ or GST as indicated. Binding of KDM2A was detected by immunoblot against the FLAG-tag. (C) Recruitment of KDM2A to the rDNA locus is augmented by HP1α. MCF7 cells were transfected with HP1α-specific siRNAs and analysed for the enrichment of the H13 region of the rDNA locus by ChIP using antibodies against KDM2A, HP1α and histone H3K9me3. Shown are the mean ± SD of the signals normalised to input of three independent experiments. KDM2A shows only little enrichment at the GAPDH locus. (D) Analysis of KDM2A and HP1α expression in siRNA-treated MCF7 cells by immunoblot. GAPDH serves as loading control. See also Figure S4.

We next verified the disruptive effect of DNA methylation seen in the SNAP experiments. KDM2A harbours a DNA-binding module consisting of a CXXC-type zinc finger domain that was recently demonstrated to bind unmethylated CpG residues and to be sensitive to DNA methylation (Blackledge et al., 2010). When FLAG-tagged KDM2A was isolated from extracts with immobilised 601-DNA (Figure S4E) binding was abolished by CpG methylation as expected. We also sought to establish whether the recruitment of KDM2A to H3K9me3-nucleosomes in the presence of HP1 could be disrupted by DNA methylation. Lane 14 in Figure 5A clearly shows that KDM2A cannot recognise H3K9me3-nucleosomes when the DNA is methylated. The simultaneous recognition of DNA and HP1 leads to a stronger association with nucleosomes. This is indicated by a more effective recruitment of KDM2A to H3K9me3-nucleosomes compared to H3K9me3-modified peptides in the presence of HP1 (compare lanes 13 and 16 in Figure 5A).

To confirm that the recruitment of KDM2A to nucleosomes through HP1 also occurs in a physiological context, we investigated whether the recently reported localisation of KDM2A to ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA) in MCF7 cells (Tanaka et al., 2010) is dependent on HP1. Indeed, down-regulation of HP1α by siRNA results in a specific decrease of HP1α and KDM2A binding, as assessed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis (Figure 5C and D).

Together these experiments confirm the observations made using SNAP and show that KDM2A recognises H3K9me3 via HP1 and that an additional interaction component is conferred by its recognition of DNA, which is sensitive to the state of methylation.

Discussion

Proteins are localised on chromatin depending on a complex set of cues derived from the recognition of histones and DNA in a modified or unmodified form. Here we present an approach (SNAP) that allows the identification of proteins that recognise distinct chromatin modification patterns. The SNAP method employs modified recombinant nucleosomes to isolate proteins from SILAC-labelled nuclear extracts and to identify them by mass spectrometry. In this study we have used nucleosomes containing a combination of methylation events on DNA (CpG) and histone H3 (K4, K9, and K27). It is apparent from our results that proteins recognising methylated nucleosomes can be influenced by (a) the DNA sequence (in a modified and unmodified form), (b) the configuration of the histone octamer, and (c) the precise combination of histone and DNA modifications. Below we discuss these modes of engagement.

(a) Recognition of DNA

The use of two distinct DNA sequences (601 or 603) in our SNAP experiments has identified proteins that recognise methyl-CpGs in a sequence specific way (e.g. ZNF295) as well as proteins that are not sequence selective (e.g. MBD2). This suggests that some proteins may have a promiscuous methyl-DNA recognition domain (i.e. recognising methylated CpG dinucleotides regardless of the surrounding DNA sequence) whereas others require a specific motif surrounding the methylated CpG site. Analysis of factors recognising CpG methylation for the presence of known domains identifies a striking number of zinc finger-containing proteins (Table S2). Our data indicate that around 50% of proteins binding to methyl-CpG and 20% of proteins excluded from methylated DNA and nucleosomes harbour a zinc finger domain, a motif already known to have methyl-CpG-binding potential (Sasai and Defossez, 2009). Interestingly, the second most prevalent domain in methyl-CpG-binding proteins (20%) is a homeobox (e.g. in HOMEZ, PKNOX1 and ZHX proteins). Homeoboxes are known DNA-binding domains but have not previously been demonstrated to bind methyl-CpG. These data raise the possibility that homeoboxes may possess a methyl-CpG recognition function.

(b) Influence of nucleosomes

When methylated 601- or 603-DNA is incorporated into nucleosomes the histone octamer appears to have an effect on the binding of certain proteins. The TFIIIC complex cannot bind a B-box effectively in the presence of an octamer, suggesting the need for remodelling activities for full access. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 is seen to bind DNA-methylated nucleosomes, but showed no binding to methyl-DNA in the absence of a histone octamer. The USF2 transcription factor is excluded from its binding site in the 601-DNA more strongly in the presence of histone octamers. These examples indicate that the histone octamer may have a steric effect on the DNA-binding of such factors or that these factors contain additional contact points with histones which results in an increased affinity to nucleosomes compared to free DNA.

(c) Regulation by a combination of DNA and histone methylation

Proteins are able to associate with nucleosomes depending on the precise status of DNA and histone methylation. UHRF1, which binds cooperatively to methyl-DNA and H3K9me3, may represent a class of proteins that have an intrinsic capacity to recognise both modifications directly since it contains a SRA domain that binds methylated DNA and a tandem Tudor and a PHD domain that can bind methylated H3K9 (Hashimoto et al., 2009). In the case of protein complexes the recognition of each modification may reside on separate subunits. We identified two protein complexes, ORC and PRC2, that are influenced by both types of modification in opposite ways. The ORC complex, including the LRWD1 protein, recognises H3K9- and H3K27- methylation in a cooperative manner with DNA methylation. This may allow for a stronger interaction of ORC with heterochromatic regions (Pak et al., 1997; Prasanth et al., 2004). The PRC2 complex, which recognises H3K27-methylation, is negatively regulated by DNA-methylation. This may enable this transcriptional repressor to associate preferentially with a specific chromatin state that is not silenced completely and can respond to external stimuli, such as poised genes. Finally, the KDM2A histone H3K36-demethylase can recognise H3K9me3 indirectly via its association with HP1 and recruitment is blocked when DNA is methylated. This disruptive effect would allow the demethylase to distinguish between distinct chromatin landscapes: it will recognise silenced genes that are marked by H3K9-methylation and HP1 but it will not dock on heterochromatic regions that carry both H3K9me3- and DNA-methylation. Together, these examples provide evidence that proteins can monitor the methylation state of both, histones and DNA, in order to discriminate between distinct states of repressed chromatin.

SNAP as a Tool for Studying Chromatin Modification Crosstalk

SNAP has several advantages over the current approaches using peptides and oligonucleotides to identify chromatin-binding factors. One advantage is that nucleosomes provide a more physiological substrate. Proteins may have a number of contact points to chromatin (histone tails, histone core, DNA) and may recognise more than one histone at a time. As a result of this multiplicity of possible interactions, SNAP will allow the identification of proteins whose affinity may be too weak to be selected for by the current methods. Our results clearly identify proteins, such as KDM2A, whose binding depends on such a physiological nucleosomal context. A second powerful advantage of SNAP is that it allows the identification of proteins that recognise multiple independent modifications on chromatin. In this study, we have analysed histone modifications in combination with DNA methylation. But it is equally possible to monitor the binding of proteins to combinations of histone modifications either on the same histone or on different histones or to use multiple nucleosomes. The SNAP approach is also suitable for modified histones generated using methyl-lysine analogues (Simon et al., 2007). But since binding affinities might be crucial for the identification of interacting proteins natural modified amino acids might be more desirable. In this regard, recent successful attempts to genetically install modified amino acids in recombinant histones are very promising (Neumann et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2009). In Summary, our findings demonstrate that chromatin modification-binding proteins can recognise distinct modification patterns in a chromatin landscape. The SNAP approach is therefore a valuable tool for studying the mechanisms by which epigenetic information encoded in chromatin modifications can be interpreted by proteins.

Experimental Procedures

Extract Preparation and Immunoprecipitation

HeLa S3 cells were grown in suspension in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS and normal arginine and lysine or 5% dialysed FBS and heavy arginine-13C6, 15N4 and lysine-13C6, 15N2 (Isotec). Cells were harvested at a density of 0.5-0.8×106 cells/ml and nuclear extracts were essentially prepared as described (Dignam et al., 1983). For both SILAC extracts three independent nuclear extracts were prepared and pooled to yield an “average” extract that compensates for differences in each individual preparation. 293T and MFC7 cells were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. 293T cells were transfected using a calcium phosphate protocol. Whole cell extracts were prepared ~36h after transfection by rotating the cells in extraction buffer (20 mM Hepes pH7.5; 300 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 20% Glycerol; 0.5% NP40; 1 mM DTT and complete protease inhibitors [Roche]) for 1 h at 4°C. HeLa S3 nuclear extracts and 293T or MCF7 whole cell extracts were snap frozen and stored in aliquots at −80°C. For coimmunoprecipitations, extracts were prepared without DTT and diluted 1:1 with 20 mM Hepes pH7.5; 1 mM EDTA; 20% Glycerol containing complete protease inhibitors. Extracts were pre-cleared and proteins immunoprecipitated with typically 5 μg of antibody and Protein-G Sepharose (GE Healthcare) or 20 μl anti-FLAG M2 agarose (Sigma).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and Immunofluorescence

For ChIPs, MCF7 cells were reverse-transfected with siRNAs against HP1α or negative control siRNA using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 48h after transfection, cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS at room temperature for 10 min and quenched with 125 mM Glycine for 5 min. After three washes with 10 ml of cold PBS cells were harvested in cold PBS supplemented with Complete Protease Inhibitor cocktail by scraping. Pellets from two 10 cm dishes were suspended in 1.6 ml of RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl; 2mM EDTA; 1% NP-40; 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS supplemented with EDTA-free complete protease inhibitors), sonicated in 15 ml conical tubes three times 10 minutes at High, 30 sec ON/OFF cycles in a cooled Bioruptor® (Diagenode) and cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 13,000 rpm. ChIPs were then performed as described (Xhemalce and Kouzarides, 2010). The PCR analysis was performed on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System using Fast SYBR® Green (Applied Biosystems). For IFs, MCF7 cells were grown in slide flasks, washed with PBS, treated for 5 min on ice with CSK buffer (10mM PIPES pH6.8, 100mM NaCl, 300mM sucrose, 3mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA and 0.5% Triton), washed again with PBS and fixed with 5% Formalin solution (Sigma) in PBS/2% sucrose. The fixed cells were incubated O/N at 4°C with 0.5μg/ml of each primary antibody, and for 1 h at RT with DAPI and the secondary antibodies. Images were acquired with an Olympus FV1000 Upright confocal microscope and processed using Adobe Photoshop® CS software.

Protein Expression and Purification

Recombinant histone proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/RIL cells from pET21b(+) (Novagen) vectors and purified by denaturing gelfiltration and ion exchange chromatography essentially as described (Dyer et al., 2004). Truncated H3.1Δ1-31T32C protein was generated in vivo by expressing a H3.1Δ1-31T32C precursor in the presence of TEV-protease. For this purpose E. coli cells harbouring the pET28a(+)-AraC-PBAD-His6TEV/pro-H3.1Δ1-31T32C plasmid were grown in LB medium containing 0.25% L-arabinose to keep TEV-protease induced. At an OD600 of 0.6 the expression of pro-hH3.1Δ1-31T32C was induced for 3 h at 37°C with 50 μM IPTG. TEV-protease processes the precursor histone H3.1 into tail-less H3.1Δ1-31T32C. The insoluble protein was extracted from inclusion bodies with solubilisation buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5; 7 M Guanidine HCl; 100 mM DTT) for 1 h at RT and passed over a Sephacryl S200 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare) in SAU-200 (20 mM NaAcetate pH5.2; 7 M Urea; 200 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA) without any reducing agents. Positive fractions were directly loaded onto a reversed phase ResourceRPC column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a gradient of 0% - 65% B (A: 0.1% TFA in water, B: 90% Acetonitrile; 0.1% TFA) over 20 column volumes. Fractions containing pure H3.1Δ1-31T32C were pooled and lyophilised. All histone proteins were stored lyophilised at −80°C. Recombinant HP1 GST-fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/RIL cells and purified by glutathione sepharose (GE Healthcare) chromatography. HP1 proteins were cleaved off the beads with biotinylated thrombin (Novagen). After removal of thrombin with streptavidin sepharose HP1 proteins were dialysed into TBS/10% glycerol, snap frozen and stored at −80°C.

Preparation of Modified Histones and Nucleosomal DNAs

For native chemical ligations lyophilised modified H3.1 1-31 thioester peptide (Almac) was incubated at a concentration of 0.56 mg/ml (~0.167 mM) with truncated H3.1Δ1-31T32C protein at 4 mg/ml (~0.333 mM) and thiophenol at 2% (v/v) in ligation buffer (6 M Guanidine HCl; 200 mM KPO4 pH7.9). The cloudy mixture was left shaking vigorously at RT for 24 h. The reaction was stopped by adding DTT to a final concentration of 100 mM, dialysed three times against SAU-200 buffer containing 5 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol, and then loaded onto a Hi-Trap SP HP column (GE-Healthcare). The ligated Histone H3 was eluted with a linear gradient from SAU-200 to SAU-600 buffer (20 mM NaAcetate pH5.2; 7 M Urea; 600 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 5 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol). Positive fractions were pooled, diluted 3-fold in SAU-0 buffer (20 mM NaAcetate pH5.2; 7 M Urea; 1 mM EDTA; 5 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol) to reduce the NaCl concentration and reloaded onto the column. Three rounds of purification were needed to yield sufficiently pure ligated histone. Following ion exchange purification, the ligated histone was dialysed against water containing 1 mM DTT, lyophilised and stored at −80°C. Nucleosomal 601- or 603-DNAs were excised from purified plasmid DNAs (Plasmid Giga Kit, Qiagen) by digestion with EcoRV and separated from the vector by PEG precipitation as described (Dyer et al., 2004). For end-biotinylation the DNA was further digested with EcoRI and the overhangs filled in with biotin-11-dUTP (Yorkshire Bioscience) using Klenow (3′->5′ exo−) polymerase (NEB). Nucleosomal biotinylated DNAs were then separated by PEG precipitation or further methylated with M.SssI CpG Methyltransferase (NEB) and then PEG-precipitated to remove small cleavage products.

Reconstitution of Nucleosomes and Nucleosome Pulldowns

Octamers were refolded from purified histones and assembled into nucleosomes with biotinylated nucleosomal DNAs by salt deposition as described (Dyer et al., 2004). Optimal reconstitution conditions were determined by titration and then kept constant for all nucleosome assembly reactions. Nucleosomes were checked on 5% native PAGE gels. For SILAC pulldowns, nucleosomes corresponding to 12.5 μg of octamer were immobilised on 75 μl Dynabeads Streptavidin MyOne T1 (Invitrogen) in the final reconstitution buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5; 250 mM KCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM DTT; supplemented with 0.1% NP40) and then rotated with 0.5 mg HeLa S3 nuclear extract in 1 ml of binding buffer (20 mM Hepes pH7.9; 150 mM NaCl; 0.2 mM EDTA; 20% Glycerol; 0.1% NP40; 1 mM DTT and complete protease inhibitors) for 4 h at 4°C. After five washes with 1 ml of binding buffer the beads from both SILAC pulldowns were pooled and bound proteins were eluted in sample buffer and analysed on 4-12% gradient gels by colloidal blue staining (NuPAGE/NOVEX, Invitrogen). For DNA and peptide pulldowns streptavidin coated magnetic beads were saturated with either biotinylated 601-DNA or H3 peptides (residues 1-21) and then used as described for the nucleosome beads.

Mass Spectrometry of Proteins and Computational Analyses

Nucleosome-bound proteins resolved on SDS-PAGE gels were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion as described (Vermeulen et al., 2010). Peptide identification experiments were performed using an EASY nLC system (Proxeon) connected online to an LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany). Tryptic peptide mixtures were loaded onto a 15-cm-long 75-μm ID column packed in-house with 3-μm C18-AQUA-Pur Reprosil reversed-phase beads (Dr. Maisch GmbH) and eluted using a 2-h linear gradient from 8 to 40% acetonitrile. The separated peptides were electrosprayed directly into the mass spectrometer, which was operated in the data-dependent mode to automatically switch between MS and MS2. Intact peptide spectra were acquired with 100,000 resolution in the FT cell while acquiring up to five tandem mass spectra in the LTQ part of the instrument. Proteins were identified and quantified by analysing the raw data files using the MaxQuant software, version 1.0.12.5, in combination with the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science), essentially as described (Vicent et al., 2009). The raw data from all forward and reverse pulldowns were processed together and filtered such that a protein was only accepted when it was quantified with at least two peptides, both in the forward and the reverse pulldown. Results from the pulldowns were visualised using the open source software package R. For the cluster analysis, the log2 ratio between the forward and reverse SILAC values (ratio H/L) of each protein was calculated. These data were clustered to identify related clades of proteins. Clustering was performed in R using the hopach package (van der Laan and Pollard, 2003). The distance between pairwise log2 ratio values was calculated using the absolute uncentered correlation distance, and agglomerative hierarchical clustering using complete linkage was performed.

Deposition of MS-related Data

The MS raw data files for nucleosome pulldowns can be accessed via TRANCHE (https://proteomecommons.org/) under the name “SILAC Nucleosome Affinity Purification”.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kevin Ford, Timothy Richmond, Bruce Stillman, Jonathan Widom, and Yi Zhang for providing materials, Helder Ferreira and Tom Owen-Hughes for advice on native chemical ligations, and Peter Tessarz and Emmanuelle Viré for experimental help. This work was supported by postdoctoral fellowships to T.B. from EMBO and HFSP, and by a fellowship to M.V. from the Dutch Cancer Society. The M.M. laboratory is supported by the Max-Planck Society for the Advancement of Science and HEROIC, a grant from the European Union under the 6th Research Framework Programme. The T.K. lab is funded by grants from Cancer Research UK and the European Union (Epitron, HEROIC and SMARTER). Tony Kouzarides is a director of Abcam Ltd.

References

- Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–124. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007;128:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge NP, Zhou JC, Tolstorukov MY, Farcas AM, Park PJ, Klose RJ. CpG islands recruit a histone H3 lysine 36 demethylase. Mol Cell. 2010;38:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer PN, Edayathumangalam RS, White CL, Bao Y, Chakravarthy S, Muthurajan UM, Luger K. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Kuchay SM, Kato H, Poleshko A, Basrur V, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Katz RA, Pagano M. KDM2A represses transcription of centromeric satellite repeats and maintains the heterochromatic state. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3539–3547. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.22.7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart MD, Corcoran CM, Wamstad JA, Bardwell VJ. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6880–6889. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00630-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KH, Bracken AP, Pasini D, Dietrich N, Gehani SS, Monrad A, Rappsilber J, Lerdrup M, Helin K. A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1291–1300. doi: 10.1038/ncb1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Horton JR, Zhang X, Cheng X. UHRF1, a modular multi-domain protein, regulates replication-coupled crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone modifications. Epigenetics. 2009;4:8–14. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.1.7370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagianni P, Amazit L, Qin J, Wong J. ICBP90, a novel methyl K9 H3 binding protein linking protein ubiquitination with heterochromatin formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:705–717. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01598-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-Kohlbrecher D, Christensen J, Vandamme J, Abarrategui I, Bak M, Tommerup N, Shi X, Gozani O, Rappsilber J, Salcini AE, et al. A functional link between the histone demethylase PHF8 and the transcription factor ZNF711 in X-linked mental retardation. Mol Cell. 2010;38:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guezennec X, Vermeulen M, Brinkman AB, Hoeijmakers WA, Cohen A, Lasonder E, Stunnenberg HG. MBD2/NuRD and MBD3/NuRD, two distinct complexes with different biochemical and functional properties. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:843–851. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.843-851.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir TW. Semisynthesis of proteins by expressed protein ligation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:249–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Hancock SM, Buning R, Routh A, Chapman L, Somers J, Owen-Hughes T, van Noort J, Rhodes D, Chin JW. A method for genetically installing site-specific acetylation in recombinant histones defines the effects of H3 K56 acetylation. Mol Cell. 2009;36:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DP, Garcia Alai MM, Kapadnis PB, Neumann H, Chin JW. Genetically encoding N(epsilon)-methyl-L-lysine in recombinant histones. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14194–14195. doi: 10.1021/ja906603s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak DT, Pflumm M, Chesnokov I, Huang DW, Kellum R, Marr J, Romanowski P, Botchan MR. Association of the origin recognition complex with heterochromatin and HP1 in higher eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;91:311–323. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth SG, Prasanth KV, Siddiqui K, Spector DL, Stillman B. Human Orc2 localizes to centrosomes, centromeres and heterochromatin during chromosome inheritance. EMBO J. 2004;23:2651–2663. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pray-Grant MG, Daniel JA, Schieltz D, Yates JR, 3rd, Grant PA. Chd1 chromodomain links histone H3 methylation with SAGA- and SLIK-dependent acetylation. Nature. 2005;433:434–438. doi: 10.1038/nature03242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthenburg AJ, Li H, Patel DJ, Allis CD. Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:983–994. doi: 10.1038/nrm2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasai N, Defossez PA. Many paths to one goal? The proteins that recognize methylated DNA in eukaryotes. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:323–334. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082652ns. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren-Knaak MA, Fry CJ, Peterson CL. A native peptide ligation strategy for deciphering nucleosomal histone modifications. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15744–15748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MD, Chu F, Racki LR, de la Cruz CC, Burlingame AL, Panning B, Narlikar GJ, Shokat KM. The site-specific installation of methyl-lysine analogs into recombinant histones. Cell. 2007;128:1003–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Okamoto K, Teye K, Umata T, Yamagiwa N, Suto Y, Zhang Y, Tsuneoka M. JmjC enzyme KDM2A is a regulator of rRNA transcription in response to starvation. EMBO J. 2010;29:1510–1522. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna SD, Li H, Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Patel DJ. How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1025–1040. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert TJ, Wong C-H. New methods for proteomic research: preparation of proteins with N-terminal cysteines for labeling and conjugation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2171–2174. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<2171::aid-anie2171>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan MJ, Pollard KS. A new algorithm for hybrid hierarchical clustering with visualization and the bootstrap. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2003;117:275–303. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen M, Eberl HC, Matarese F, Marks H, Denissov S, Butter F, Lee KK, Olsen JV, Hyman AA, Stunnenberg HG, et al. Quantitative interaction proteomics and genome-wide profiling of epigenetic histone marks and their readers. Cell. 2010;142:967–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicent GP, Zaurin R, Nacht AS, Li A, Font-Mateu J, Le Dily F, Vermeulen M, Mann M, Beato M. Two chromatin remodeling activities cooperate during activation of hormone responsive promoters. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xhemalce B, Kouzarides T. A chromodomain switch mediated by histone H3 Lys 4 acetylation regulates heterochromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 2010;24:647–652. doi: 10.1101/gad.1881710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Qin L, Jiang F, Wu B, Yue W, Xu F, Rong Z, Yuan H, Xie X, Gao Y, et al. Structure of human spindlin1. Tandem tudor-like domains for cell cycle regulation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:647–656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.