Abstract

Objective

To describe the attitudes of U.S. neurologists specializing in dementia toward the use of amyloid imaging in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

Methods

A cross-sectional electronic physician survey of dementia specialists at U.S. medical schools was performed.

Results

The response rate for the survey was 51.9% (135/260). Greater than 83% of respondents plan to use amyloid imaging to evaluate patients for Alzheimer disease. Most respondents intend to use amyloid imaging as an adjunctive diagnostic modality to confirm (77%) or rule-out (73%) a diagnosis of Alzheimer dementia; 24% plan to use amyloid imaging to screen asymptomatic individuals for evidence of cerebral amyloid. Specialists who do not intend to use amyloid imaging (16%) express concern about the cost (73%), the usefulness (55%), and likelihood of patient (55%) and clinician (59%) misinterpretation of findings. The need for patient pre-test counseling was endorsed by a large percentage (92%) of dementia specialists (higher than for genetic testing (82%)).

Conclusions

Dementia specialists, particularly young specialists, are likely to be early adopters of amyloid imaging. Assuming ready availability, this new technology would be used as a confirmatory test in the evaluation of Alzheimer disease, as well as a screening tool for asymptomatic pathology. Specialists recognize the complexity of interpreting amyloid imaging findings and the need for patient counseling before undergoing testing.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, amyloid, PET, neuroimaging, biomarker, diagnosis

Introduction

In 2004 it was demonstrated that amyloid could be imaged in the brains of living humans, offering for the first time a window into the in vivo status of cerebral amyloid at various points in time, [1] and in turn, the prospect of a new tool for improving diagnosis,[2] treatment efficacy tracking,[3] and risk stratification[4] in Alzheimer disease. Subsequent development of fluorine-based ligands to substitute for C11-based ligands promises wider access to this technology.[5] The FDA has recently approved an amyloid marker (florbetapir) for clinical use.[6] Indications and range of future use of amyloid imaging are not certain. Cost, reimbursement and clinician adoption are sure to be critical factors in clinical adoption of this technology. Neurologists who specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of dementia, in particular, will be at the forefront of deciding on amyloid imaging use. Thus, the attitudes of dementia specialists may be a bellwether for patterns and frequency of amyloid imaging use in dementia assessment and management generally.

A survey was conducted of neurologists practicing primarily at academic medical centers and specializing in dementia asking them about their anticipated use of amyloid imaging in the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Specialists’ views on the usefulness of this modality in diagnosis and challenges to its clinical adoption were investigated.

Materials and Methods

A physician survey of prospective clinical amyloid imaging use was developed in consultation with colleagues in neurology and dementia. They did not participate in the final survey. The study and survey were reviewed and approved by the Oregon Health & Sciences University IRB. The survey was made available for respondents on the Internet using the services of www.surveymonkey.com. See Supplemental Data for a copy of the survey. As amyloid imaging is not currently available in clinical practice, for all questions respondents were asked to assume that imaging was FDA approved, available at a local institution, and covered by insurance.

Neurologists with expertise in dementia at American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) accredited medical schools in the United States were identified through neurology department and academic aging and memory center websites. “Specialists” were identified if they were listed as faculty in a dedicated memory disorders center, listed dementia care as a subspecialty, or were specialists in neurodegenerative disease with publications specifically focused on dementia diagnosis or care listed in pubmed.org (pubmed search terms “dementia” or “Alzheimer’s disease).

Public e-mail addresses for neurologists at academic centers were identified by this search. Potential participants (N=260) were sent an email invitation with an Internet web address link to the survey. Respondents were given 4 weeks to complete the survey. Up to three e-mail reminders were sent to potential respondents after the initial invitation.

Responses were anonymous. Survey design precluded completion of more than one survey per computer. Responses were collected using surveymonkey.com; responses were imported to and analyzed with Microsoft Excel.

Results

Survey invitations were e-mailed to 260 individual neurologists and 135 surveys were fully completed. The response rate was 51.9%. Respondent demographic characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Since the survey used categorical rather than continuous variables for responses, a mean and median are not reported. The majority of respondents, 64%, devoted more than 75% of their practice to the care of patients with a primary cognitive complaint. 89% of respondents had completed a fellowship or post-doctoral training in dementia, geriatrics, or neurodegenerative disorders. The largest sub-group of respondents (37%) had completed training 20 years ago or more.

Table 1.

Respondent Demographics, N=135, response options in bold (n (%))

| Percentage of practice devoted to cognitive disorders (primary cognitive complaint) | < 10% 2(1.5%) | 11–25% 14(10.4%) | 26–50% 12(8.9%) | 51–75% 20(14.8%) | >75%87 (64.4%) |

| Time since completion of residency or fellowship training (yrs) | <5 19(14.1%) | 5–10 26(19.3%) | 11–15 21(15.6%) | 16–20 19(14.1%) | >20 50(37.0%) |

| Fellowship or post-doctoral training in dementia or neurodegeneration | Yes 120(88.9%) | No 15(11.1%) | |||

| Clinical care effort (%) | <10%14(10.4%) | 10–25% 57(42.2%) | 26–50%31(22.9%) | 51–75% 26(19.2%) | >75% 7(5.2%) |

| Region of U.S. | Northeast42(31.1%) | Midwest 37(27.4%) | South 26(19.3%) | West 30(22.2%) | |

| United Stares Veterans Affairs practice | Yes 28 (20.7%) | No 107(79.3%) | |||

| Male or female | Male109(80.7%) | Female26(19.3%) |

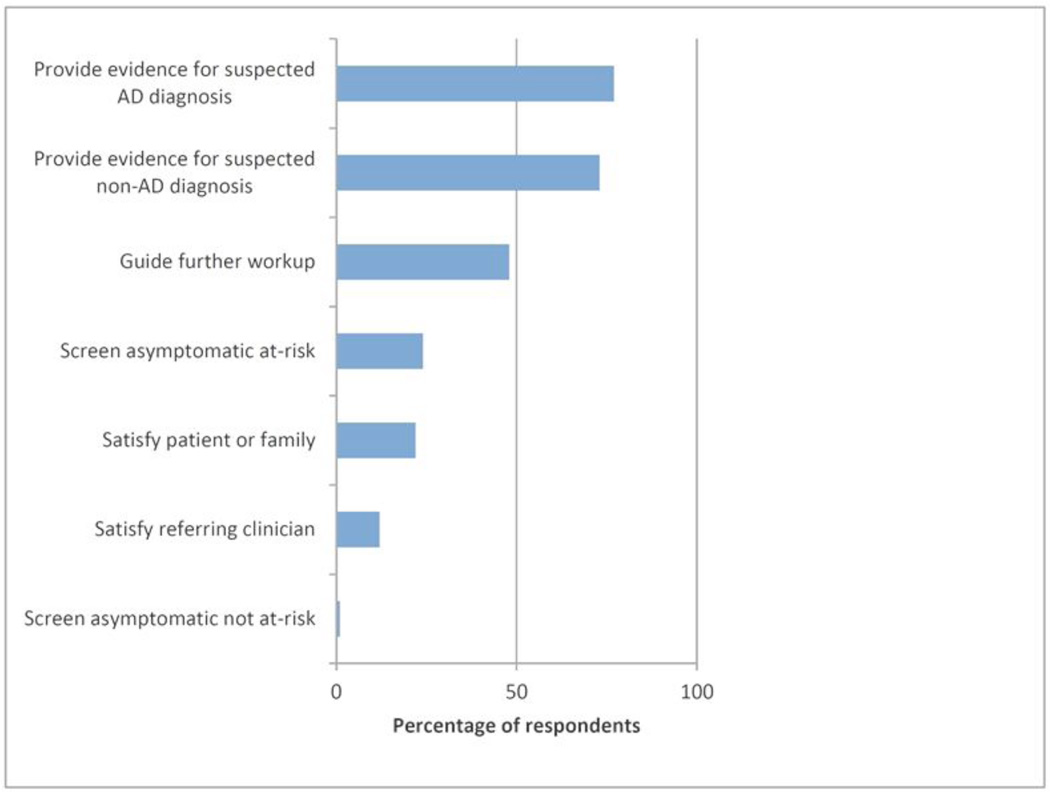

Respondents were asked if they intended to use amyloid imaging to help diagnose or predict Alzheimer disease and, if so, how they planned to use it. Respondents were allowed to select more than one choice. A large majority (84%) affirmed an intention to use amyloid imaging, and most (88%) planned to use this to diagnose at least one patient each month (Table 2). The intent to use amyloid imaging correlated with the extremes of years in clinical practice, with 100% (19/19) of those with fewer than 5 years in practice planning to use amyloid imaging and only 70% (35/50) of those with 20 or more years of practice intending to use amyloid imaging. Many intended to use amyloid imaging to provide evidence for (77%) or against (73%) a presumed diagnosis of Alzheimer disease, with nearly a quarter of respondents (24%) intending to use amyloid imaging to screen asymptomatic individuals (Figure 1). Of note, respondents who did not plan to use amyloid imaging (16%) cited lack of improvement on existing diagnostic tools (55%), imprudent use of resources (73%), and patient (55%) and clinician (59%) likely misinterpretation of results as reasons for not using amyloid imaging.

Table 2.

Specialist Intended Use of Amyloid Imaging in Diagnosis of Alzheimer Dementia

| Intend to use amyloid imaging to help diagnosis AD | Yes: 113 (83.7%) | No: 22 (16.3%) | |||

| Frequency of intended use (patients/month) | <1: 14 (12.3%) | 1–2: 39 (34.5%) | 3–5: 34 (30.1%) | 6– 10: 18 (15.9%) | >11 8 (7.1%) |

Figure 1. Indications for Use of Amyloid Imaging.

Respondents who indicated that they intended to use amyloid imaging to diagnose or predict Alzheimer disease (n=117) were asked “I will use amyloid imaging to:” Respondents were allowed to choose more than one indication.

Respondents were asked to identify what factors would influence their decision to use amyloid imaging and what factors would influence the use of amyloid imaging by others. Figure 2 summarizes this data. Respondents were allowed to select more than one choice. Most felt that scientific literature (92%) and professional body recommendations or practice parameters (76%) would influence their decision. Factors cited as important to whether amyloid imaging will be commonly used in medical practice also included scientific literature (89%) and professional body recommendations and practice parameters (79%), but many respondents cited additional influences, such as patient requests for testing (47%), referring clinician requests for testing (41%), and colleague experience (42%). Of note, no (0/135) respondent felt their decision to use amyloid imaging would be influenced by media coverage, yet nearly half of respondents (48%) felt media coverage of testing would influence whether amyloid imaging became commonly used in clinical practice.

Figure 2. Influence on self and other clinician use of amyloid imaging.

Respondents were asked to identify influences on their own intended us of amyloid imaging and to identify influences on the use of amyloid imaging generally. Respondents were allowed to choose more than one influence for each question.

Respondents were asked to identify which clinicians would be aided in diagnosis by amyloid imaging and which clinicians were prepared to counsel patients about the results of amyloid imaging. Most respondents felt that amyloid imaging would improve diagnostic accuracy of neurologists with specialized training (77%) but only (50%) felt that the diagnostic accuracy of neurologists without specialized dementia training would be improved by use of amyloid imaging.

Most respondents felt that patients should be counseled on the meaning of amyloid imaging before undergoing testing (92%). This response was higher than for a similar question asked about the need for pre-test genetic counseling in Alzheimer disease (82%). Most respondents (85%) felt that neurologists with specialized training in dementia possessed the requisite skills to counsel patients on the meaning of amyloid imaging, with a minority feeling that neurologists without specialized dementia training (10%) possess these skills. Respondents endorsed the need for training of all involved clinicians on how to counsel patients about the meaning of amyloid imaging.

Discussion

Results of this survey indicate that if amyloid imaging becomes readily available, without significant barriers of access and cost, academic neurologists specializing in dementia will be leaders in use of amyloid imaging. Amyloid imaging will be used as an adjunctive tool in evaluation of symptomatic patients by many dementia specialists and as a screening tool in asymptomatic patients by some clinicians. Dementia specialists recognize that adoption of amyloid imaging as a diagnostic modality raises important questions about cost, misinterpretation of results, and influence on clinician use.

Neurologists specializing in dementia are poised to be “early adopters” of this new technology.[7] Our data suggests that younger clinicians are less skeptical of this new technology and more likely to be early adopters, with 100% (19/19) of those with fewer than 5 years in practice versus only 70% (35/50) of those with 20 or more years of practice planning to use amyloid imaging. Prior to the recent FDA approval of florbetapir, experience with amyloid imaging as a diagnostic modality has been limited to dementia specialists involved in research, such as the large multi-center Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging (ADNI) study.[8] The use of PET, SPECT, and CSF biomarkers has not become standard practice in evaluation of dementia in the community,[9] perhaps due to the need for expertise in interpretation of findings or challenges of non-specialist third party payment authorization. Dementia specialists currently possess the professional, institutional, and epistemic authority to lead early adoption of amyloid imaging.

The cost of amyloid imaging as a diagnostic tool in dementia evaluation will be an important issue going forward, particularly if the technology proves to be effective and becomes widely adopted. The ultimate cost or reimbursement for amyloid PET is not yet known. An FDG-PET scan at our institution costs over $4000. With an annual incidence of 454,000 new diagnoses of dementia in the U.S. (climbing to 615,000 in 2030),[10] use of amyloid imaging in even a minority of new cases will substantially increase costs associated with dementia diagnosis. For instance, using $4000 as a high figure (costs would hopefully drift down as the radiopharmaceutical enters wider clinical practice, but could be higher at introduction), we estimate that even if only 25% of newly diagnosed individuals in the U.S. were to undergo an amyloid PET scan, the cost would equal the entire annual NIH budget allocated to Alzheimer’s disease research.[11] If testing is to screen asymptomatic individuals, as our results suggest it will be, the costs could be much higher. Screening of 25% of those aged 75 and older (4 million by U.S. 2000 Census data[12]) would cost over $16 billion per year. These cost estimates, albeit rough, do not consider the potential cost of multiple scans over a lifetime, such as if amyloid PET is used to follow patients’ amyloid burdens over time or monitor response to future amyloid-targeted therapy. The use of amyloid imaging in the evaluation of a high prevalence condition, such as dementia, will inevitably raise important individual and societal questions about cost and availability. Our survey did not specifically address the costs of amyloid imaging as we were focused on identifying the perceived clinical value of this new tool, independent of cost considerations.

Meaningful interpretation of amyloid imaging results will be the predominant clinical challenge facing early adopters. Almost 50% of cognitively normal cases are found at autopsy to have neuritic plaques of moderate or frequent density.[13] The importance of placing a “positive” amyloid scan within the context of an appropriately trained clinician’s comprehensive dementia evaluation is paramount. This is particularly true if amyloid imaging finds use as a screening tool. Misinterpretation of testing results could have substantial psychological, economic, and health consequences for patients. Specialist and non-specialist training in how to best use amyloid imaging and how to counsel patients on the results will need to be developed.

This survey had several limitations. The survey instrument had not been validated. Given the timeliness of this topic and the well-known impediments to physician survey participation, it was not deemed practical to formally evaluate the survey’s psychometric properties. The survey represents the responses of approximately 52% of neurologists with specialized training or practice in dementia at U.S. medical schools. This represents a good response rate for a physician survey.[14] Nonetheless, selection bias cannot be ruled out. It is possible that those who chose to respond were those already favorably disposed to amyloid imaging. However, even with this potential bias, given the very strong positive response toward using amyloid imaging among the responding neurologists, it is likely that at a minimum, there will be a healthy debate about using this technology in the specialist community. The subject population did not include non-academic clinicians, non-neurologist clinicians (e.g., geriatricians), or neurologists without specialized training in dementia even though such groups are commonly involved in dementia diagnosis. The choice to limit respondents to academic neurologists with specialized training in dementia was consistent with the survey goal of exploring the specialized role of this group in early adoption of amyloid imaging technology. Surveying other relevant groups will be important future work, particularly if this technology is directly marketed to patients and community providers without expertise in dementia diagnosis. If amyloid imaging technology follows recent marketing trends in the pharmaceutical industry,[15] analogous ethical questions about the appropriate role of patients, providers, and policy makers in adoption of new technology will need to be addressed.[16]

The study had other possible limitations. Some neurologists with specialized training in dementia may not have been properly identified given a reliance on institutionally maintained websites and publicly available email addresses. Respondents were asked in considering their views on amyloid imaging to assume hypothetically that cost and availability of testing would not be prohibitive, and focus solely on the clinical utility of the test. It is possible that some respondents, despite instruction, included cost or availability considerations into their responses. While limitations of a hypothetical test with these parameters are recognized, the authors take the clinical utility of amyloid imaging in general to be an independent preliminary data point worth establishing, particularly given the unpredictability of future availability or cost. The survey did not assess how future developments in dementia care, such as effective preventative or therapeutic interventions, might affect opinions of amyloid imaging. While such hypothetical scenarios would be interesting to consider, the variables introduced by their inclusion would have been difficult to limit and control for in a brief survey.

New NIH recommendations for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease places greater importance on new diagnostic modalities, such as in vivo amyloid testing, in diagnosing AD.[17] Though, it should be noted, biomarkers, such as amyloid imaging, are not required for rendering a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and the exact role of biomarkers in neurodegenerative and normal aging processes is still being elucidated. It is important for clinicians and policy makers to know how dementia specialists intend to use this new technology. Future research will need to identify barriers to appropriate use of amyloid imaging. Attention to these gaps before widespread adoption of this innovative technology is warranted.

This study suggests that academic neurologists with specialized training in dementia will be early adopters of amyloid imaging. Though this new technology would be used as a confirmatory test in evaluation of Alzheimer disease, some specialists expect to use this as a screening tool for asymptomatic pathology. Dementia specialists acknowledge the complexity of interpreting amyloid imaging findings and the need for patient counseling before undergoing testing.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A Yanming W, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Huang G, Estrada S, Ausén B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Långström B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villemagne VL, Ong K, Mulligan RS, Holl G, Pejoska S, Jones G, O’Keefe G, Ackerman U, Tochon-Danguy H, Chan JG, Reininger CB, Fels L, Putz B, Rohde B, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Amyloid imaging with 18F-florbetaben in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1210–1217. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.089730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathis CA, Lopresti BJ, Klunk WE. Impact of amyloid imaging on drug development in Alzheimer’s disease. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34(7):809–822. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thal LJ, Kantarci K, Reiman EM, Klunk WE, Weiner MW, Zetterberg H, Galasko D, Praticò D, Griffin S, Schenk D, Siemers E. The role of biomarkers in clinical trials for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(1):6–15. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000191420.61260.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe CC, Villemagne VL. Brain Amyloid Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(11):1733–1740. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S. Alzheimer diagnosis possible with scan. The Wall Street Journal. 2012 Apr 9; Sect. B1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(15):1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagust WJ, Bandy D, Chen K, Foster NL, Landau SM, Mathis CA, Price JC, Reiman EM, Skovronsky D, Koeppe RA. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative positron emission tomography core. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert M, DeCarli C, DeKosky S, de Leon M, Foster NL, Fox N, Frank R, Frackowiak R, Jack C, Jagust WJ, Knopman D, Morris JC, Petersen RC, Reiman E, Scheltens P, Small G, Soininen H, Thal L, Wahlund L, Thies W, Weiner MW, Kchachaturian Z. The use of MRI and PET for clinical diagnosis of dementia and investigation of cognitive impairment: A consensus report of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(4):169–173. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed January 19, 2012]; http://report.nih.gov/rcdc/categories.

- 12. [Accessed January 19, 2012]; http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-10.pdf.

- 13.Sonnen JA, Santa Cruz K, Hemmy LS, Woltjer R, Leverenz JB, Montine KS, Jack CR, Kaye J, Lim K, Larson EB, White L, Montine TJ. Ecology of the aging human brain. Archives of Neurology. 2011;68(80):1049–1056. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donohue JM, Cevasco M, Rosenthal MB. A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(7):673–681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Illes J, Kann D, Karetsky K, Letourneau P, Raffin TA, Schraedley-Desmond P, Koenig BA, Atlas SW. Advertising, patient decision making, and self-referral for computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(22):2415–2419. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rosso MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.