Abstract

Objective

The role of substance abuse (SA) and depression on paternal parenting has recently gained attention in the research literature. Both SA and depression have been associated with negative parenting in fathers, but studies to date have not examined the mediating role depression may play in the association of SA and fathering.

Methods

SA, depression and parenting data were reported by 87 fathers presenting for SA evaluation. Bootstrap mediation modeling was conducted to determine the role of depression on the association between SA and negative parenting.

Results

Depression is a significant mediator of the relationship between the severity of fathers’ drug use and negative parenting behaviors. Fathers who had concerns about parenting or wanted help to improve the parent-child relationship had significantly higher symptoms of depression.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms in fathers entering substance abuse treatment have implications for both the severity of drug abuse and negative parenting behaviors.

There is ample research related to mothering in the context of a host of psychosocial and psychiatric difficulties. In particular, examination of the impact of maternal depression on mothers’ parenting has been the focus of a large body of literature (Lovejoy et al., 2000; Gelfand & Teti, 1990; Carter et al., 2001). Examination of fathering in the context of substance abuse and other psychiatric difficulties has received much less attention (McMahon & Rounsaville, 2002; McMahon, Winkel, & Rounsaville, 2008; Stover, McMahon, & Easton, 2010). Although more limited than the literature on mothering, research indicates fathering in the context of substance abuse and psychiatric difficulties can yield more negative parenting (Eiden, Chavez, & Leonard, 1999; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2002; Eiden & Leonard, 2000; Fals-Stewart, Kelley, Fincham, Golden, & Logsdan, 2004; McMahon, et al., 2008). Further understanding the mechanisms that lead to maladaptive parenting in the context of substance abuse can have significant intervention implications allowing clinicians to target specific symptoms and characteristics in their work with clients to help decrease negative parenting and improve functioning within the family system as a whole.

Co-morbidity of substance abuse and depression in men

Data from the National Institute of Drug Abuse suggests that individuals with a mood or anxiety disorder are twice as likely to have comorbid substance abuse or dependence (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2010). While women tend to have higher rates of depression than men (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Matthews, & Carrano, 2007) men have higher rates of comorbid depression and polysubstance abuse or dependence (5.9 % vs. 3.8%) and higher rates of comorbid depression and other types substance abuse or dependence (36.3% vs. 20.7%) relative to women (Fava et al. 1996). Yet, to our knowledge studies have not explored the relationships between substance abuse, depression and negative parenting behaviors such as aggression, hostility, rejection and neglect by fathers.

Paternal Parenting and Substance Abuse

Studies reveal that fathers with a history of alcohol and/or drug abuse report higher levels of parenting stress and poorer communication with their child (Blackson, et al., 1999). In a population of drug-abusing men, McMahon et al. (2008) found that opioid-dependent fathers had more limited definitions of what it meant to be a father, had poorer relationships with their child's biological mother, had poorer views of themselves as fathers, and reported less fathering satisfaction relative to their non substance-abusing peers. However, there were no significant differences in the frequency of self-reported positive or negative parenting behavior. Eiden et al. (1999) found that relative to a non-substance abusing community sample, fathers who abused alcohol had more negative father-infant interactions as measured by low paternal sensitivity, positive affect, and verbalizations towards their infants. Fathers who were abusing alcohol had higher levels of negative affect and elicited lower infant responsiveness relative to fathers who were not abusing alcohol. Of particular interest to the present study was the finding that for fathers, depression mediated the relationship between his alcoholism and sensitivity toward his infant. Other studies have found paternal alcoholism to be associated with negative family interactions for fathers of school aged children (El-Sheikh & Buckhalt, 2003; El-Sheikh & Flanagan, 2001) and adolescents (King, & Chassin, 2006; (Jacob, Kahn, & Leonard, 1991), but did not examine depression's role in this association. The present study expands on this finding, looking at the relationships between drug and alcohol abuse severity, depression, and negative parenting behaviors that might be consistent with child maltreatment in a clinical sample entering treatment for substance abuse.

Paternal Parenting and Depression

Although it has not been studied as extensively in fathers as in mothers, depression in fathers has been negatively associated with time spent with the child (father-child engagement) and the quality of the co-parenting relationship. It has also been positively associated with parental aggravation and stress (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Matthews, & Carrano, 2007; Simons, Lorenz, Wu, & Conger, 1993; Simons, Whitbeck, Rand, & Melby, 1990) and father-child conflict (Kane & Garber, 2004) Although prior research supports that both substance abuse and depression contribute to negative parenting for men, the combination of depression and substance abuse have not been well studied in fathers. Given the higher comorbidity of depression and substance abuse in men and some literature suggesting that negative parenting behaviors in substance abusing women are more associated with psychopathology than drug abuse (Hans, Bernstein, & Henson, 1999), examination of such co-occurring symptoms in fathers and the impact on negative parenting is warranted.

The current study

To our knowledge, an examination of psychiatric symptoms such as depression that may be contributing to both the severity of substance abuse and parenting behaviors has not been explored in a sample of men entering substance abuse treatment. The present study examines the relationship between substance abuse and negative parenting, looking at paternal depression as a factor mediating this relationship. The investigation also explores the relationship between paternal depression and fathers’ desire to attain additional treatment to improve their parenting skills. In the context of substance abuse treatment, this study has important clinical implications. If depression does, in fact, mediate the relationship between substance abuse and negative parenting, providing treatment for fathers’ depression may improve both their substance abuse and parenting skills.

Methods

Sample

The sample included 87 randomly selected fathers applying for treatment at a Forensic Drug Diversion Clinic from January 2009-March 2011. These men were referred by the court system for substance abuse evaluation and treatment. Men were eligible for treatment if they reported being the father of a child under the age of 18.

Procedure

At the time of their initial assessment appointment at the clinic, participants completed paper and pencil questionnaires and clinicians gathered demographic information from the men. Data was compiled by trained research assistants and entered into an SPSS database for analysis.

Measures

Data included basic demographics (e.g. age, ethnicity, living with significant other, relationship status, employment, number and ages of biological children) and responses to specific questions about whether the fathers in the study would be interested in a parenting class, they had concerns about their child, or if they wanted to discuss fatherhood/ parenting issues as part of their treatment (coded as 1= yes and 0= no). Additionally, men completed paper and pencil questionnaires related to their drug and alcohol use, depressive symptoms and parenting behaviors on the following standardized measures:

The Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) is a 25- question self-report instrument (Selzer, 1971) used widely to assess the severity of alcoholism. Each item utilizes weighted scoring, with two of the items amounting to the number of times an event occurs. The MAST has shown high validity as both a screening test and as a measurement of severity in alcoholism (Westermeyer, Yargic, & Thuras, 2004).

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982) is a self-report questionnaire used to assess drug use problems. It includes 28 yes/no items that measure symptoms of drug use and dependence. Items are weighted 0 or 1, and responses are summed to arrive at a total score ranging from 0 to 28. Higher scores indicate more severe drug use problems. The DAST has shown good validity and reliability (Cocco & Carey, 1998; El-Bassel et al., 1997; McCann, Simpson, Ries, & Roy-Byrne, 2000).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire which measures symptoms of depression over a 2-week period. The Inventory uses a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from 0 to 3. The total score is calculated by summing the ratings on each scale and can range from 0 to 63 with higher scores indicating greater depression severity (Quilty, Bagby, & Zhang, 2010; Stulz & Crits-Christoph, 2010).

The Parental Acceptance Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ; Rohner & Khaleque, 2005) is a 60-item, self-report measure that documents frequency of (a) warm-affectionate, (b) hostile-aggressive, (c) rejectful, and (d) neglectful parenting behavior. Respondents rate the occurrence of different parenting behaviors along a 4-point scale that ranges from Almost never true (0) to Almost always true (3). To calculate the overall negative parenting score, items are summed from each scale.

Analytic Plan

We first conducted Pearson product moment correlation on the variables of interest to determine an association between the independent substance abuse variables (MAST and DAST totals) and depression (BDI total) and negative parenting (PARQ Total). If correlations exist between the MAST and DAST and the PARQ, we will test our meditational hypotheses using a bootstrapping method. Mediation is often tested using the causal steps approach popularized by Baron and Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986), or the product-of-coefficients approach developed by Sobel (Sobel, 1982, 1986). Both procedures employ parametric techniques that assume multivariate normality of the sampling distribution of total and specific indirect effects, which can be problematic except in very large samples (MacKinnon, 2000; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The bootstrapping approach to mediation does not impose such an assumption, a process that simultaneously increases power and maintains reasonable control over the Type I error rate (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Bootstrapping is a nonparametric re-sampling technique that empirically generates an approximation of the sampling distribution. The procedure yields point estimates and percentile confidence intervals for indirect and total effects. In the present study, bootstrap percentile confidence intervals were further improved using bias-correction and acceleration, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The sample included 87 men who were fathers of a child under the age of 18. The mean age of the sample was 35.4 years (SD= 9.74) with an average of 12.2 years (SD =2.02) of education. Fifty percent of the sample was employed at least part-time. Male subjects had the following racial composition: African American (42.5%), Caucasian (21.8%), Hispanic (11.5%), Puerto Rican (5.7%), and other ethnicity3.4%. Men reported a mean of 6.54 days (SD = 8.13) of drinking in the last month, a mean MAST score of 3.66 (SD= 3.70), and a mean DAST score of 4.01 (SD = 4.04). Approximately fifty-two percent reported alcohol as their primary drug of choice followed by cannabis at 23% and cocaine at 5.7%. Only 4.6% of men reported use of opiates, PCP or multiple substances. Nine percent of the sample denied significant abuse of drug or alcohol despite a substance abuse related arrest. Sixty-five percent of men were referred for evaluation due to an arrest for domestic violence while under the influence of alcohol or substances. Others were referred by probation or the court as a result of other substance-related charges or failed drug screenings are part of their probation requirements. The mean BDI score was 6.69 (SD = 8.97).

Participants reported having from 1 to 5 children with an average of 2.27 (SD=1.21). Children ranged in age from one to 18 years of age. Forty percent reported having children with multiple women and 32% reported living with at least one of their children. Twenty-seven percent reported having some concerns related to their child or children and 22% percent reported specific concerns about fatherhood or their relationship with their children. Twenty three percent indicated they felt they would benefit from a parenting class to learn to manage their children and 18% reported they would like to discuss fatherhood or child-related issues as part of their treatment.

Pearson product moment correlations revealed a significant association of drug abuse with depression (r = .59, p = .00) and alcohol abuse with depression (r = .24, p = .04). Additionally, depression was significantly positively associated with negative parenting behaviors (r = .63, p = .002). Drug abuse was also significantly correlated with negative parenting (r = .26, p = .03), but alcohol abuse was not. Given the lack of correlation between alcohol abuse severity and negative parenting, no mediation testing was done between alcohol abuse and father's parenting behavior.

Mediation Models

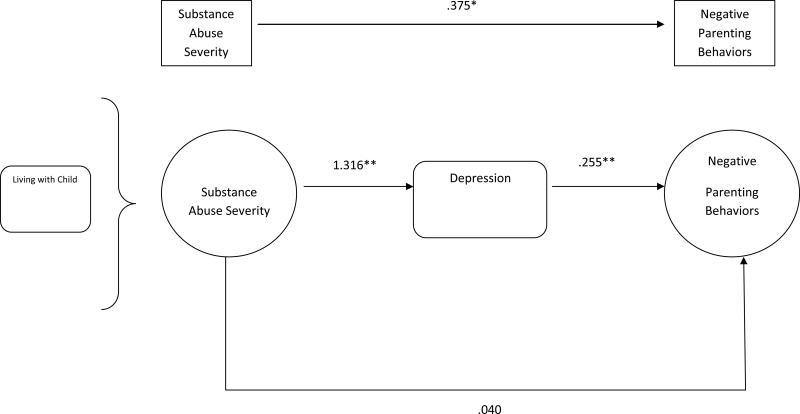

The bootstrap results (see Figure 1) indicated that the total effect of fathers’ drug abuse severity on their negative parenting behaviors (total effect = .38, p = .04) became non-significant when fathers’ depression as measured by the BDI was included as a mediator in the model (direct effect of substance abuse = .04, p = .85). Furthermore, the analyses revealed, with 95% confidence, that the total indirect effect (i.e., the difference between the total and direct effects) of fathers’ drug abuse on negative parenting through depression as the mediator was significant, with a point estimate of .13 and a 95% BCa (bias-corrected and accelerated; see Efron, 1987) bootstrap confidence interval of .09 to .78. Thus, the depression mediated the association between substance abuse and negative parenting behaviors of fathers.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model

Given the findings that depression is associated with more negative parenting, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine whether fathers who reported that they wanted help with parenting or fatherhood issues as part of their treatment had higher levels of depression. Analysis of variance was used to compare fathers who (a) had concerns about fatherhood or their relationship to their child (or children) vs. those who did not (b) said they would like to participate in a parenting class vs. those who did not (c) said they wanted to discuss fathering issues as part of their treatment vs. those who did not (d) were interested in an assessment of their child (or children) vs. those who did not based on severity of their symptoms of depression. As shown in Table 1, fathers who had concerns about fatherhood or their relationship to their child reported significantly higher symptoms of depression. In addition, fathers who said: 1) they would be interested in a parenting class, 2) wanted to discuss fathering issues as a part of their treatment, and 3) they would be interested in an assessment of their child reported significantly higher symptoms of depression than fathers who were not interested in these services.

Table 1.

Association of Depression and Wish for Help Related to Fathering as Part of their Substance Abuse Treatment

| Variable | N | F | Mean(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns Related to Fathering | Yes | 15 | 12.14** | 12.05(12.92) |

| No | 57 | 4.40(5.88) | ||

| Parenting Class | YES | 13 | 26.31** | 15.07(13.32) |

| No | 45 | 3.93(4.98) | ||

| Want Father Issues as Part of Tx | Yes | 13 | 4.09* | 11.38(12.02) |

| No | 59 | 5.47(8.40) | ||

| Assessment | Yes | 2 | 9.83** | 13.31(12.09) |

| No | 52 | 5.07(7.62) |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Discussion

The study results reveal, in this sample of fathers presenting for a substance abuse evaluation, the positive association between the severity of fathers’ drug use and negative parenting behaviors was mediated by symptoms of depression. This is consistent with findings that parenting behaviors in substance abusing mothers are more associated with psychopathology than drug use (Hans, et al., 1999). Our findings are also consistent with previous studies that have reported depression in fathers is associated with negative parenting (Bronte-Tinkew, et al., 2007; Simons, et al., 1993; Simons, et al., 1990). This suggests that symptoms of depression are particularly important to assess in fathers who are presenting for drug abuse treatment to determine how depression may be associated with both drug abuse and negative parenting that may be associated with child maltreatment (e.g. hostility, aggression, rejection). Targeting fathers’ depression could have important clinical implications for reducing the severity of drug abuse and improving the quality of the father-child relationship. This, in turn, could improve child mental health and overall well-being.

Interestingly, no association was found between alcohol severity and negative parenting in this sample. This is contrary to other studies indicating alcohol use is associated with a host of more negative parenting behaviors in fathers. This inconsistency may be due to the wide age range of children in our sample and the use of self-report measures rather than direct observations of fathers and children conducted in other studies (Edwards, Eiden, & Leonard, 2004; Eiden, et al., 1999; Eiden & Leonard, 2000). The range of self-reported alcohol abuse severity was also low with a mean MAST score of 3.66. It may be that a sample of more severe alcohol abuse and dependence would yield results consistent with other studies. An alternate explanation is that men who were primarily abusing alcohol were less forthcoming about both their alcohol use and their parenting behaviors.

Also of importance was the finding that men who had concerns about fatherhood or their relationship to their child were more likely to report significantly higher symptoms of depression. Furthermore, fathers with higher depression symptoms were more likely to state they would be interested in a parenting class, wanted to discuss fathering issues as a part of their treatment, and were interested in an assessment of their child. This indicates that fathers presenting for substance abuse evaluation who have significant depression symptoms may be most open to and benefit from a treatment program that incorporates a focus on parenting and the father-child relationship.

Limitations

This study was meant to provide a preliminary examination of the association of depression to the substance abuse and parenting behaviors of fathers presenting for a substance abuse treatment evaluation at a forensic drug diversion clinic and the implications for assessment and treatment. Although the results provide important preliminary evidence for the mediating role of depression in substance abuse severity and negative parenting behaviors, it has several limitations. First, clients were specifically referred to the clinic for an arrest and court involvement. Whether these results translate to the broader population of substance abusing men in a variety of treatment settings is unclear. The study depended on fathers’ self-report of their substance abuse, depression and parenting behaviors. Collateral informants such as partners or co-parents reports about the parenting behaviors of fathers or direct observations of father-child interactions would have strengthened the validity of the results.

Conclusions

Overall, these findings point to the benefits of evaluating both depressive symptoms and parenting behaviors and concerns of fathers entering substance abuse treatment. Depression may provide a particularly important intervention target for fathers with co-occurring drug abuse and depressive symptoms that may improve outcomes for both fathers and their children. Additionally, fathers with co-occurring drug abuse and depressive symptoms may be particularly interested and open to incorporating parenting interventions into their substance abuse treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) K23 DA023334 (Stover). The authors would like to acknowledge Rodney Webb III, M.A. for his work on this project.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackson TC, Butler T, Belsky J, Ammerman RT, Shaw DS, Tarter RE. Individual traits and family contexts predict sons’ externalizing behavior and preliminary relative risk ratios for conduct disorder and substance use disorder outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56(2):115–131. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Moore KA, Matthews G, Carrano J. Symptoms of Major Depression in a Sample of Fathers of Infants: Sociodemographic Correlates and Links to Father Involvement. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(1):61–99. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Garrity-Rokous FE, Chazan-Cohen R, Little C, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Maternal Depression and Comorbidity: Predicting Early Parenting, Attachment Security, and Toddler Social-Emotional Problems and Competencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric Properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in Psychiatric Outpatients. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(4):408–414. [Google Scholar]

- Efon B. Better Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82(397):171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Chavez F, Leonard KE. Parent-infant interactions among families with alcoholic fathers. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:745–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Schilling R, Schinke S. Assessing the utility of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in the workplace. Research on Social Work Practice. 1997;7:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Kelley ML, Fincham FD, Golden J, Logsdan T. Emotional and behavioral problems of children living with drug-abusing fathers: comparisons with children living with alcohol-abusing and non-substance-abusing fathers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(2):319–330. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Abraham M, Alpert J, Nierenberg AA, Pava JA, Rosenbaum JF. Gender differences in Axis-I comorbidity among depressed outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;38:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM. The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10(3):329–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hans SL, Bernstein VJ, Henson LG. The role of psychopathology in the parenting of drug-dependent women. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:957–977. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children's psychopathology, and father-child conflict. A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In: Rose J, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahweh, NJ: 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- McCann BS, Simpson TL, Ries R, Roy-Byrne P. Reliability and Validity of Screening Instruments for Drug and Alcohol Abuse in Adults Seeking Evaluation for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. American Journal on Addictions. 2000;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TJ, Winkel JD, Rounsaville BJ. Drug abuse and responsible fathering: A comparative study of men enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment. Addiction. 2008;103(2):269–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse . Comorbidity: Addiction and Other Mental Illnesses (NIH Publication no. 10-5771) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, D.C.: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/PDF/RRComorbidity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilty LC, Bagby RM, Zhang KA. The Latent Symptom Structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Outpatients with Major Depression. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22(3):603–608. doi: 10.1037/a0019698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Khaleque A, editors. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. 4th ed. Rohner Research Publications; Storrs, CT: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The Quest for a New Diagnostic Interview. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1971;127(12):89–94. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lorenz FO, Wu C, Conger RD. Social network and marital support as mediators and moderators of the impact of stress and depression on parental behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(2):368–381. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Melby Husband and Wife Differences in Determinants of Parenting: A Social Learning and Exchange Model of Parental Behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52(2):375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7(4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Sociological Methodology. 1986;16:159. [Google Scholar]

- Stover CS, McMahon TJ, Easton C. The impact of fatherhood on treatment response for men with co-occurring alcohol dependence and intimate partner violence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2010;37(1):74–78. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.535585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulz N, Crits-Christoph P. Distinguishing Anxiety and Depression in Self-Report: Purification of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory-II. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;66(9):927–940. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer J, Yargic I, Thuras P. Michigan Assessment- Screening Test for Alcohol and Drugs (MAST/AD): Evaluation in a Clinical Sample. The American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:151–162. doi: 10.1080/10550490490435948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]