Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the expected change in the prevalence of male circumcision (MC)–reduced infections and resulting health care costs associated with continued decreases in MC rates. During the past 20 years, MC rates have declined from 79% to 55%, alongside reduced insurance coverage.

Design

We used Markov-based Monte Carlo simulations to track men and women throughout their lifetimes as they experienced MC procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections and accumulated associated costs. One-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were used to evaluate the impact of uncertainty.

Setting

United States.

Participants

Birth cohort of men and women.

Intervention

Decreased MC rates (10% reflects the MC rate in Europe, where insurance coverage is limited).

Outcomes Measured

Lifetime direct medical cost (2011 US$) and prevalence of MC-reduced infections.

Results

Reducing the MC rate to 10% will increase lifetime health care costs by $407 per male and $43 per female. Net expenditure per annual birth cohort (including procedure and complication costs) is expected to increase by $505 million, reflecting an increase of $313 per forgone MC. Over 10 annual cohorts, net present value of additional costs would exceed $4.4 billion. Lifetime prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection among males is expected to increase by 12.2% (4843 cases), high- and low-risk human papillomavirus by 29.1% (57 124 cases), herpes simplex virus type 2 by 19.8% (124 767 cases), and infant urinary tract infections by 211.8% (26 876 cases). Among females, lifetime prevalence of bacterial vaginosis is expected to increase by 51.2% (538 865 cases), trichomoniasis by 51.2% (64 585 cases), high-risk human papillomavirus by 18.3% (33 148 cases), and low-risk human papillomavirus by 12.9% (25 837 cases). Increased prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection among males represents 78.9% of increased expenses.

Conclusion

Continued decreases in MC rates are associated with increased infection prevalence, thereby increasing medical expenditures for men and women.

State governments are increasingly eliminating Medicaid coverage for neonatal male circumcision (MC), with 18 states having abolished coverage.1 Meanwhile, the MC rate in the United States has decreased substantially.

Although the prevalence of circumcision among men born in the 1970s and 1980s remained stable at approximately 79%,2,3 the MC rate decreased to 62.5% in 1999 and to 54.7% by 2010.4,5 Because Medicaid pays for more than one-third of all in-hospital MCs, further limitations to state coverage hinder access to MC and are likely to lead to further decreases.4,6 Private third-party payers are also decreasing coverage.4 Within Europe, where routine MC insurance coverage is rare, MC rates are 15.8% in the United Kingdom and 1.6% in Denmark.7–9

Male circumcision rate decreases have persisted despite growing evidence of medical benefit. Three randomized controlled trials in Africa demonstrated that MC was associated with a lowered risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), low-risk and high-risk human papillomavirus (LR-HPV and HR-HPV, respectively), and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2).1,10–16 One of the trials also showed that female partners of circumcised men had a reduced risk of LR-HPV, HR-HPV, bacterial vaginosis (BV), and trichomoniasis.17,18 Observational studies of MC in the United States have demonstrated similar results,19–22 suggesting that efficacy estimates from the African trials are applicable to the United States. Furthermore, observational studies and meta-analyses have suggested that MC also offers a protective benefit against infant male urinary tract infections (UTIs).23–25

Each year, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States cause substantial morbidity and mortality and cost an estimated $16.9 billion in direct medical costs alone.26 A comprehensive cost analysis of MC, incorporating recent randomized trial data on protection against multiple STIs, has not been conducted but is essential for guiding health care policy.

METHODS

A Markov-based27 Monte Carlo simulation model was constructed using TreeAge Pro Suite 2012 (TreeAge Inc) to estimate the change in lifetime costs and infection prevalence associated with decreasing MC rates in the United States, incorporating risks from all health conditions demonstrated to be significantly reduced by MC.1,11–14,17,18,28,29 Individual men and women of a birth cohort were observed throughout their lifetimes as they experienced potential MC procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections and accumulated associated costs.

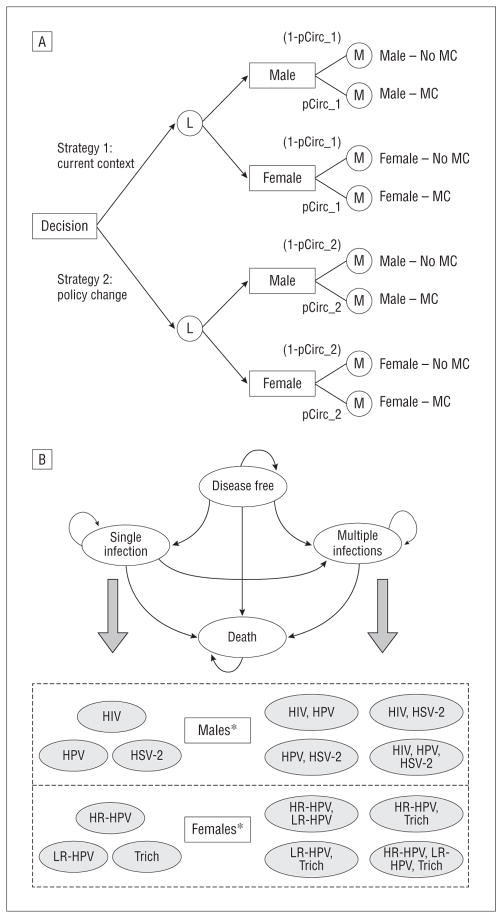

Each potential health condition was modeled as a Markov state, and transition probabilities between states were defined using published incidence estimates and preventative efficacy from MC trial and meta-analysis data. Among males, MC procedure-related events included the procedure and possible complications, and MC-reduced infections included infant UTIs, HIV, HSV-2, HR-HPV, and LR-HPV. Male circumcision–reduced infections among females, incorporated in a separate Markov process, included BV, trichomoniasis, HR-HPV, and LR-HPV. Females did not experience MC procedure-related events but instead experienced protective benefits of MC through their association with circumcised males. The model (Figure, A) compared cost and infection outcomes for an individual within a “current context” strategy to the expected outcomes within a “policy change” strategy, characterized by lower MC rates. The MC rate under the current context strategy (79%) reflected characteristics of current adult men who were born before the rate decrease during the past 20 years and who are currently experiencing risks from MC-reduced STIs.2,3 The impact of uncertainty in input parameters, including cost, incidence, and preventative efficacy, was assessed using univariate and probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Figure.

Markov-based model structure and bubble diagram. A, First, a decision node leads to a strategy choice, in which strategy 1 is defined by the current male circumcision (MC) rate and strategy 2 is defined by a decreased MC rate. Individuals are separated by sex using a logic node (L) and enter 1 of 2 Markov processes (M). The 2 processes involve identical states but differ in MC-dependent parameters. The probability of running through an MC process is defined by the MC rate under the selected strategy, with males experiencing the MC procedure and subsequent health benefits and with females experiencing protective benefits of MC from associating with circumcised males. B, Males and females transition through separate models, each beginning in a “disease-free” state. During each 1-year cycle of the simulation, individuals may remain in their current state or transition to another possible state, acquiring a single infection or multiple infections at once. HIV indicates human immunodeficiency virus; HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus type 2; LR-HPV, low-risk human papillomavirus; pCirc, probability of MC protection under the given strategy; trich, trichomoniasis. *Infant male urinary tract infections and female bacterial vaginosis were incorporated but not modeled as separate Markov states.

A societal perspective was adopted and future costs were discounted to birth year by 3% annually.30 Only direct medical expenses were included, and cost parameters were adjusted to 2011 US$ using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

THE MODEL

The individual microsimulation captured MC procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections through a series of 1-year cycles, beginning at birth. Because incidence data were unavailable or negligible for individuals aged 1 to 12 years, potential infections during this period were excluded. During each cycle, individuals faced age- and sex-specific risks from background mortality as well as risks from single or concurrent infections. As they acquired health conditions, individuals transitioned to corresponding Markov states and accumulated associated costs (Figure, B). The probability of transitioning to a health state depended on annual incidence and MC preventative efficacy for the infection(s). All individuals began in a “disease-free” state and ultimately transitioned to an absorbing “death” state, either from background mortality or, for males who contracted HIV, from HIV-related causes. The model was evaluated under 2 strategies, each incorporating one Markov subtree using parameters associated with no MC and another subtree using parameters associated with MC (Figure, A). Under each strategy, the portion of males (or females) running through each subtree was defined by the MC rate.

Male circumcision procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections occurring only in the first year after birth—the procedure, potential complications,24,31 and infant male UTIs23–were modeled as nonrecurrent risks, and associated costs were incorporated as initial rewards, accumulating only in the first stage of the simulation.

MODEL INPUTS AND ASSUMPTIONS

Model input parameters included data from demographic surveys, published literature on incidence and cost, and MC preventative efficacy estimates from randomized trials for STIs and meta-analyses for UTIs (Table 1). Age-independent incidence parameters and efficacy estimates were sampled at the beginning of each simulation from beta distributions. Cost and age-specific incidence parameters were varied by 25% in either direction using an adjustment factor sampled from a triangular distribution (median[range],1 [0.75–1.25]).

Table 1.

Model Parameters: Base-Case Values and Ranges for Sensitivity Analysisa

| Input Parameter | Base-Case (Range) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Infant male, ages birth-1 y | ||

| Circumcision | ||

| Current rate, %, adult men in United States | 79 (60–80) | Xu et al,2 Sansom et al3 |

| Decreased rate, %, in Europe, without insurance coverage | 10 | Dave et al,7 Frisch et al,8 WHO9 |

| Procedure cost, $ | 291 (146–437) | Sansom et al,3 CDC5 |

| Complication rate, % | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | CDC,5 AAP,24 Weiss et al31 |

| Complication cost, $ | 185 (130–235) | Schoen et al32 |

| Infant male urinary tract infection | ||

| Incidence, uncircumcised, % | 2.15 (1.9–2.4) | Schoen et al23 |

| Cost, uncircumcised, $ | 2055 (1541–2569) | Schoen et al23 |

| Cost, circumcised, $ | 1225 (919–1531) | Schoen et al23 |

| MC efficacy | 0.10 (0.08–0.12) | Schoen et al23 |

| Adult male, ages 13–100 y | ||

| HIV | ||

| Incidence, ages 13–29 y, per 100 000 | 39.9 | CDC33 |

| Incidence, ages 30–39 y, per 100 000 | 64.1 | CDC33 |

| Incidence, ages 40–49 y, per 100 000 | 45.8 | CDC33 |

| Incidence, ages ≥50 y, per 100 000 | 10.2 | CDC33 |

| Portion due to heterosexual transmission (%) | 15.7 (6–20) | Sansom et al,3 CDC33 |

| Life expectancy posttreatment | 24.2 (22.0–26.0) | Schackman et al,34 Harrison et al35 |

| Lifetime cost, $ | 388 754 (29 565–485 942) | Schackman et al,34 Hutchinson et al,36 Chen et al37 |

| MC efficacy | 0.49 (0.29–0.81) | Gray et al13 |

| HPV | ||

| HPV incidence, per 100 000, varies by ageb,c | 35.6–450.9 | Hernandez et al,38 Chesson et al39 |

| HPV lifetime cost per case, $, varies by agec,d | 509–1307 | Chesson et al,39 Hu and Goldie,40 Kim and Goldie41 |

| HR-HPV MC efficacy | 0.67 (0.51–0.89) | Gray et al,14 Gray et al42 |

| LR-HPV MC efficacye | 0.67 (0.51–0.89) | Gray et al,14 Tobian et al15 |

| HSV-2 | ||

| Incidence, ages 13–19 y, per 100 000 | 770 | Armstrong et al43 |

| Incidence, ages 20–29 y, per 100 000 | 780 | Armstrong et al43 |

| Incidence, ages 30–39 y, per 100 000 | 146 | Armstrong et al43 |

| Incidence, ages 40–49 y, per 100 000 | 400 | Armstrong et al43 |

| Incidence, ages ≥50 y, per 100 000 | 260 | Armstrong et al43 |

| Lifetime cost, per seropositive case, $ | 779 (584–974) | Chesson et al44 |

| MC efficacyf | 0.72 (0.56–0.92) | Tobian et al15 |

| Adult female, ages 13–100 y | ||

| HPV | ||

| HR-HPV incidence, per 100 000, varies by ageb,c | 0–485 | Chesson et al39 |

| HR-HPV lifetime cost, $, varies by agec,d | 0–34 203 | Chesson et al39 |

| HR-HPV MC efficacy | 0.77 (0.62–0.93) | Wawer et al18 |

| LR-HPV incidence, per 100 000, varies by agec | 0–558 | Chesson et al39 |

| LR-HPV lifetime cost, $d | 507 (380–634) | Kim and Goldie41 |

| LR-HPV MC efficacy | 0.83 (0.69–1.00) | Wawer et al18 |

| BV | ||

| Prevalence among ages 14–49 y, % | 29.2 (27.2–31.3) | Allsworth and Peipert45 |

| Portion symptomatic, % | 25 (15–42) | Allsworth and Peipert,45 Koumans et al46 |

| Median age at infectiong | 30.2 | Allsworth and Peipert45 |

| Cost per case, $h | 83 (62–104) | Carr et al47 |

| Portion of recurrent cases, % | 60 (40–70) | Marazzo,48 Bradshaw et al49 |

| MC efficacyi | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | Gray et al17 |

| Trichomoniasis | ||

| Incidence, symptomatic, ages 13–14, per 100 000 | 5 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Incidence, symptomatic, ages 15–24, per 100 000 | 130 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Incidence, symptomatic, ages 25–34, per 100 000 | 168 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Incidence, symptomatic, ages 35–64, per 100 000 | 92 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Lifetime cost, ages 13–14 y, $j | 111 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Lifetime cost, ages 15–24 y, $j | 175 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Lifetime cost, ages 25–34 y, $j | 168 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| Lifetime cost, ages 35–64 y, $j | 130 | Owusu-Edusei et al50 |

| MC efficacyi | 0.52 (0.05–0.98) | Gray et al17 |

Abbreviations: AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; BV, bacterial vaginosis; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, high risk; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus type 2; LR, low risk; MC, male circumcision; WHO, World Health Organization.

All cost parameters include direct medical costs only and have been converted to 2011 US$. Incidence parameters are reported as annual rates. Where no upper age limit for incidence was provided, an upper limit was assumed, after which the incidence was modeled as a decreasing function toward zero. Efficacy estimates are expressed as incidence rate ratios and based on an intention-to-treat analysis.

Overall incidence estimate for HPV among men includes incident cases of penile cancer and genital warts due to HPV. Overall incidence estimate for HR-HPV among women includes incident cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (stages 1–3), cervical cancer, vulvar cancer, and vaginal cancer due to HPV.

Age groups reported as 13–19 y, followed by intervals of 5 y.

Lifetime cost reported is an expected value for an incident case of HPV among men (or an incident case of HR-HPV among women) using a weighted sum of the costs of penile cancer and genital warts (or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [stages 1–3], cervical cancer, vulvar cancer, and vaginal cancer).

The incidence rate ratio for MC to reduce LR-HPV is assumed to be the same as the MC incident rate ratio for HR-HPV because the prevalence risk ratios were similar.14,42

Efficacy value is expressed as a hazard ratio.

Median age at infection was estimated using adjusted odds ratios of BV prevalence by age group.

Each case is assumed to require 1 Gram stain for diagnosis, 1 general office visit, and treatment with oral metronidazole (500 mg), twice per day for 7 days.

Efficacy parameters for BV and trichomoniasis were not available as incident rate ratios, but because these are acute, treatable infections, prevalence risk ratios were used in the model.

Lifetime cost calculated as the product of cost per case and number of expected cases.

Transition probabilities between Markov states, specified using incidence parameters, did not vary by individual background characteristics or health history because there is no clear evidence of causality between infections.28,51 Average age and sex-specific incidence estimates were used for all individuals in the cohort, accounting for a combination of individuals at high and low risk of STIs.

Under a no-MC Markov subtree, incidence of MC-reduced infections among males described the annual acquisition rate among susceptible uncircumcised men, and the incidence of MC-reduced infections among females described the annual acquisition rate among susceptible women associating with uncircumcised men. Similarly, incidence under an MC subtree reflected characteristics of circumcised males or among females associating with circumcised men. Because published incidence rates incorporated benefits of MC at the current level, incidence under a no-MC subtree was derived as follows: where

“pMC” was the MC rate, “(Incidence|MC)” indicated “Incidence” conditional on MC status, and “MC_Effect” was defined as incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the infection.

Incidence rate ratios for STIs were drawn from randomized trials following heterosexual males and female partners in Rakai, Uganda, and were based on an intention-to-treat analysis.1,14,15,17,18 Although 2 additional trials were conducted,11,12 the Ugandan trial reported conservative efficacy estimates and was the only trial to evaluate female partners.1,17,21 Observational studies among US cohorts support an association between MC and decreased STI risk.19,20,22

Although MC status was explicitly modeled among males, the transmission dynamics leading to protective effects or potential infection among females was not detailed. Instead, females faced the same preventative effects from MC as female partners in the trial,17,18,21 with the MC rate under each strategy defining the portion of females experiencing MC protective benefits.

Efficacy estimates for BV, trichomoniasis, and male LR-HPV were reported only as prevalence risk ratios and were not available as IRRs.17 While BV was modeled as a potentially prevalent infection, trichomoniasis, a relatively transient infection,52 was incorporated as potentially incident, and the reported prevalence risk ratio was used as a proxy for the IRR. Because the prevalence risk ratio reported for LR-HPV was similar to the prevalence risk ratio reported for HR-HPV,15 the IRR for HR-HPV was used as the efficacy parameter for LR-HPV.14 Low-risk and HR-HPV were modeled together as a single condition for men, so a single IRR parameter was used.

Individuals who acquired an infection accumulated a single cost at the time of infection, modeled as a transition reward, to account for any expected direct medical expenses experienced throughout a lifetime as a result of the condition. The cost associated with HIV assumed an 8.1-year gap between infection and beginning treatment.34

The probability of a male developing HIV was drawn from age-specific incidence estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention33 and excluded cases of mother-to-child transmission. The incidence at each age was assumed constant across each age interval with reported estimates and between ages 50 to 65 years, after which a decrease to an incidence of 0 at age 100 years was modeled. The portion of HIV due to heterosexual transmission was an average rate across ages.33 Because the MC effect on nonheterosexually transmitted HIV is unclear (ie, among men who have sex with men and injection drug users),53 no preventative efficacy was assumed for these cases. The probability of a male with MC of age i contracting HIV was

where,

and

The term “pHetero” is the portion of cases attributable to heterosexual transmission, and “eHIV” is the MC IRR for HIV. The probability of male HIV infection at age i without MC was

Estimates of life expectancy after initiating treatment were used to account for death from HIV-related causes.35

Symptomatic HPV acquisition among males incorporated only infections resulting in penile cancer or genital warts. The probability of developing symptomatic HPV was calculated from the sum of age-specific incidence estimates of penile cancer38 and age-specific prevalence estimates of genital warts, which were used to proxy incidence because these data were unavailable.39 Only cases of each condition attributable to HPV40 were included. Penile cancer was the only HPV-associated cancer among males considered because it is the only type reduced by MC. The expected cost per HPV case was the weighted sum of costs for penile cancer and genital warts.40

The probability of a male developing HSV-2 was calculated from age-specific incidence rates,43 and similarly to the method described for HIV, a decrease in incidence was modeled after age 65 years. The expected cost for HSV-2 was reported per seropositive case, assuming that 17% of seropositive cases were symptomatic.44,54

Women were evaluated for prevalence of BV 4 times during the simulation to reflect prevalence within each of 4 age groups. Incidence estimates were unavailable and prevalence is a reasonable proxy for the incidence of transient infections. Age-specific prevalence reported from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey45 was combined with the probability of being symptomatic45–48 to estimate the portion of women expected to have symptomatic infections during each age interval. Females who contracted symptomatic BV during an interval were not susceptible to reinfection during subsequent age ranges. The expected cost per infected female accounted for possible recurrence within 12 months of initial infection45,47–49 and included expenses for a diagnostic Gram stain, a general office visit, and standard antibiotic treatment.47 Age at infection was sampled for each of the 4 time frames.

Age-specific incidence estimates of trichomoniasis included only symptomatic cases50 and accounted for possible lifetime recurrence. Because cost per episode varied by age at infection, cost parameters were age specific.

Parameters for female HPV were estimated as described for males. However, HR-HPV and LR-HPV were modeled separately because MC efficacy differed. Incidence of HR-HPV incorporated age-specific estimates for HPV-attributable cases of cervical cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia stages 1 to 3, vaginal cancer, and vulvar cancer,39 assuming that these conditions were mutually exclusive.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For each strategy, simulation data were extracted to determine the expected cost change for an individual, considering each sex separately and considering outcomes across an entire birth cohort of 4 million (defined by a 0.51:0.49 male to female sex ratio). The expected change in expenditure per foregone MC procedure was calculated by dividing the difference in expected costs for the entire cohort between scenarios of the current MC rate (79%) and of a decreased rate (10%) by the difference in procedures between these scenarios. Lifetime infection prevalence was also evaluated under each MC rate strategy. The base-case was analyzed using 500 000 simulations. During probabilistic sensitivity analysis, 1000 simulations of 10 000 individual trials each were run, sampling system-level parameters (costs, efficacy, and incidence) at the beginning of each simulation and individual-level parameters (sex, age at death, age at BV infection, and HIV-related mortality) at the beginning of each trial. One-way sensitivity analysis was run with 200 000 trials to explicitly test for changes in outcomes at extreme values of HIV and MC procedure costs.

RESULTS

Under the base-case scenario, reducing MC rates from the current levels among sexually active men to current levels in Europe (10%), where MC is not routinely covered by insurance, would increase lifetime direct medical costs of MC-reduced infections by $407 for each male and $43 for each female (Table 2). These costs accumulate to almost $916 million for each annual birth cohort. After considering MC procedure and complication expenses, net health care costs would increase by more than $505 million, reflecting an increased expenditure of $313 per foregone MC procedure. This expenditure increase is driven primarily by male HIV (78.9%), infant male UTIs (6.3%), and female HR-HPV (6.8%) (Table 3). More modest decreases in the MC rate yielded similar lifetime cost and infection prevalence increases.

Table 2.

Base-Case Analysis: Expected Change in Lifetime Cost of MC Procedure-Related Events and MC-Reduced Infections

| Variable | MC Rate, %

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 79 (Current) | 50 | 25 | 20 | 10 | 0 | |

| Men | ||||||

| Cost per individual, $a | 3259 | 3345 | 3419 | 3437 | 3465 | 3494 |

| Net increase in cost, $b | 86 | 160 | 178 | 206 | 235 | |

| Increase in MC-reduced infection cost, $c | 171 | 318 | 350 | 407 | 465 | |

| Women | ||||||

| Cost per individual, $a | 222 | 240 | 256 | 259 | 265 | 272 |

| Net increase in cost, $b | 18 | 34 | 37 | 43 | 50 | |

| Annual birth cohort, 4 milliond | ||||||

| Total cost, $, millionsa | 7083 | 7294 | 7477 | 7519 | 7588 | 7659 |

| Net increase in cost, $, millionsb | 211 | 394 | 436 | 505 | 576 | |

| Increase in MC-reduced infection cost, $, millionsc | 384 | 715 | 787 | 916 | 1046 | |

Abbreviation: MC, male circumcision.

Cost includes lifetime direct medical expenses for all MC procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections.

Net increase in costs due to MC procedure-related events (procedure and complications) and MC-reduced infections, under each “policy change” strategy to the “current context” MC rate = 79% strategy.

Increase in costs due only to MC-reduced infections, comparing outcome under each “policy change” strategy with the “current context” MC rate = 79% strategy.

Assumes a sex distribution of 0.51 (male)/0.49 (female).

Table 3.

Base-Case Analysis: Increase in Lifetime Prevalence of MC-Reduced Infections in Annual Birth Cohort Compared With “Current Context” Strategya

| Variable | MC Rate, %

|

Total Cost Increase, %b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 25 | 20 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Male MC-reduced infections, entire birth cohort | ||||||

| HIV (% increase) | 2053 (5.2) | 3768 (9.5) | 4161 (10.5) | 4843 (12.2) | 5530 (13.9) | 78.9 |

| HPV (% increase) | 24 196 (12.3) | 44 717 (22.8) | 48 829 (24.9) | 57 124 (29.1) | 65 434 (33.3) | 1.2 |

| HSV-2 (% increase) | 52 416 (8.3) | 97 631 (15.5) | 106 621 (16.9) | 124 767 (19.8) | 142 792 (22.7) | 4.5 |

| Infant UTI (% increase) | 11 234 (88.6) | 20 937 (165.0) | 22 936 (180.8) | 26 876 (211.8) | 30 756 (242.4) | 6.3 |

| Female MC-reduced infections, entire birth cohort | ||||||

| HR-HPV (% increase) | 14 084 (7.8) | 26 003 (14.3) | 28 290 (15.6) | 33 148 (18.3) | 37 976 (20.9) | 6.8 |

| LR-HPV (% increase) | 10 870 (5.4) | 20 278 (10.1) | 22 151 (11.0) | 25 837 (12.9) | 29 546 (14.7) | 0.6 |

| BV (% increase) | 224 572 (21.3) | 421 976 (40.1) | 460 219 (43.7) | 538 865 (51.2) | 617 306 (58.7) | 1.4 |

| Trichomoniasis (% increase) | 27 084 (21.5) | 50 541 (40.0) | 55 186 (43.7) | 64 585 (51.2) | 73 886 (58.5) | 0.4 |

Abbreviations: BV, bacterial vaginosis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, high risk; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus type 2; LR, low risk; MC, male circumcision; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Assumes an annual birth cohort of 4 million, with a sex distribution of 0.51 (male)/0.49 (female). Increase in prevalence is measured using the “current context” MC rate = 79% strategy as a baseline.

Represents percentage of total expected cost increase in expenses for MC-reduced infections attributable to the respective condition. Calculated as an average percentage across all calculated “policy change” strategies.

Lifetime infection prevalence of all MC-reduced infections increased under all decreased MC rate strategies compared with the current context strategy. Among males in a birth cohort of 4 million, cases of infant male UTIs increased by 26 876 (211.8%), HIV infections increased by 4843 (12.2%), HPV infections increased by 57 124 (29.1%), and HSV-2 infections increased by 124 767 (19.8%) under a 10% MC rate (Table 3). Among females, cases of BV increased by 538 865 (51.2%), trichomonas infections increased by 64 585 (51.2%), HR-HPV infections increased by 33 148 (18.3%), and LR-HPV infections increased by 25 837 (12.9%).

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the increased prevalence and lifetime direct medical costs of MC-reduced infections persisted after accounting for uncertainty in cost, efficacy, and incidence parameters (Table 4). Univariate sensitivity analysis indicated that cost savings associated with increased MC coverage would persist while the cost of HIV treatment is greater than $120 000 to $125 000 and while the cost of the MC procedure is less than $640 to $660.

Table 4.

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis: Expected Change in Lifetime Cost and Prevalence of MC Procedure-Related Events and MC-Reduced Infections

| Variable | MC Rate, %

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 79 (Current) | 50 | 25 | 20 | 10 | 0 | |

| Lifetime direct medical costs | ||||||

| Men | ||||||

| Cost per individual, $a | 3310 | 3406 | 3490 | 3507 | 3541 | 3575 |

| Net increase, $b | 96 | 179 | 196 | 230 | 264 | |

| Increase in infection cost, $c | 181 | 337 | 368 | 432 | 495 | |

| Women | ||||||

| Cost per individual, $a | 222 | 241 | 257 | 261 | 267 | 273 |

| Net increase, $b | 19 | 35 | 39 | 45 | 51 | |

| Annual birth cohort, 4 milliond | ||||||

| Total cost, $, millionsa (95% CI) | 7188 (5146–9751) | 7422 (5247–10 160) | 7623 (5392–10 652) | 7664 (5425–10 696) | 7746 (5494–10 791) | 7829 (5499–10 961) |

| Net increase, $, millionsb | 233 | 435 | 476 | 558 | 640 | |

| Increase in infection cost, $, millionsc | 406 | 756 | 827 | 969 | 1110 | |

| Increase in lifetime cases of MC-reduced infections in annual birth cohortd | ||||||

| Male MC-reduced infections, entire birth cohort | ||||||

| HIV (% increase) | 2139 (5.3) | 4000 (10.0) | 4368 (10.9) | 5126 (12.8) | 5883 (14.7) | |

| HPV (% increase) | 23 757 (12.1) | 44 224 (22.6) | 48 378 (24.7) | 56 488 (28.9) | 64 696 (33.1) | |

| HSV-2 (% increase) | 53 286 (8.4) | 99 133 (15.7) | 108 342 (17.2) | 126 646 (20.1) | 144 969 (23.0) | |

| Infant UTI (% increase) | 11 416 (89.3) | 21 171 (165.5) | 23 147 (181.0) | 27 069 (211.7) | 30 888 (241.5) | |

| Female MC-reduced infections, entire birth cohort | ||||||

| HR-HPV (% increase) | 14 296 (7.9) | 26 527 (14.7) | 29 022 (16.0) | 33 894 (18.7) | 38 718 (21.4) | |

| LR-HPV (% increase) | 10 815 (5.4) | 20 102 (10.0) | 21 993 (11.0) | 25 707 (12.8) | 29 465 (14.7) | |

| BV (% increase) | 253 484 (24.0) | 466 880 (44.2) | 510 548 (48.3) | 599 042 (56.7) | 687 317 (65.1) | |

| Trichomoniasis (% increase) | 32 299 (25.6) | 60 065 (47.5) | 65 736 (52.0) | 76 925 (60.8) | 88 047 (69.6) | |

Abbreviations: See Table 3.

Cost includes lifetime direct medical expenses for all MC procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections.

Net increase in costs from MC procedure-related events (procedure and complications) and MC-reduced infections, under each “policy change” strategy to the “current context” MC rate=79% strategy.

Increase in costs due only to MC-reduced infections, comparing outcome under each “policy change” strategy to the “current context” MC rate=79% strategy.

Assumes a sex distribution of 0.51 (male)/0.49 (female).

COMMENT

There are an estimated 19 million new STIs annually in the United States, which cost the health care system $17 billion each year in direct medical expenses.55 Therefore, methods to curb STI incidence have both substantial health benefit and financial impact on a strained health care system. This model suggests that reducing MC rates to levels seen in countries where MC is not covered by insurance (10%) would lead to an expected increase in lifetime direct medical costs of $505 million annually. For each year that MC rates continue to approximate 50%,5 the US health care system can expect to pay $211 million more than it would have paid had MC rates remained at their levels during the 1980s. During a 10-year time span, these costs would accumulate to nearly $2 billion. In the event that MC rates were to decrease to 10%, net present value of additional costs over 10 annual birth cohorts would need to exceed $4.4 billion.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively analyze the cost and health impact of MC. All male and female STIs that have been shown through trials to be associated with MC were incorporated, as well as infant male UTIs, which have been well established by observational studies and meta-analyses to be partially averted by MC.23,56 Potential complications of the MC procedure were also considered.

Reversing MC rate trends may seem financially unappealing in the short run because cost savings from averted MC-reduced infections accumulate over a lifetime. However, more than 6% of savings, representing 14% of procedure cost, are experienced in the same year as the procedure. The favorable economic evaluation in this study is supported by a cost-effectiveness analysis of MC in the United States that was limited to HIV acquisition among heterosexual men.3

The model compared the prevalence of and expenditure on MC-reduced infections between the current environment and scenarios of reduced MC rates. Because the large majority of men who are currently sexually active (and thus currently at risk of experiencing MC-reduced infections) are at least 20 years old, the baseline current context scenario evaluated was characterized by MC prevalence among these men (79%).2 The prevalence of MC has decreased dramatically in just the past 20 years, at a rate of approximately 1% per year.3–5 Although a 10% MC prevalence in the United States may not be likely in the short run, the MC rate in countries such as Denmark, which does not offer routine insurance coverage, is only 1.6%.8 Because future MC prevalence in the United States is unknown, the model also evaluated scenarios characterized by MC rates of 50%, 25%, 20%, 10%, and 0%.

This analysis has several limitations and likely results in a conservative estimate of lifetime cost increases associated with decreased MC rates. First, although the Markov-based model allowed for infection acquisition throughout each individual’s lifetime, it did not incorporate transmission events or contextual changes in infection prevalence across the cohort or changes in cost values, which might have occurred during the simulation. This study also did not account for variation in incidence at the individual level due to risk-taking behavior or condom use but instead used average incidence rates across individuals and assumed that background characteristics were balanced across each strategy. Male circumcision has been shown to have even higher protective efficacy among high-risk individuals.15 It is also unlikely that MC would result in moral hazard, leading to decreased rates of other preventative behaviors, such as condom use.57 In addition, the model is limited by the Markovian assumption: transition probabilities depended on the present state but not on any of the previous states. However, this assumption was reasonable for the infections considered because one STI does not necessarily cause others.51

This model examined the accumulated lifetime direct medical costs for a specific set of possible MC procedure-related events and MC-reduced infections, which represents a limited portion of all possible MC-related expenses. Although cost parameters incorporated the diagnosis and treatment of an MC-reduced condition for infected individuals, they did not include subsequent costs due to increased risks from other relevant conditions (birth complications, other STIs, etc). Furthermore, an individual’s infection may have caused externalities by placing susceptible individuals at even higher risk of acquisition, but these costs were not included. Finally, only direct medical costs were assessed, ignoring direct non-medical costs (eg, patient transportation) and all indirect costs (eg, patient and caregiver productivity loss). Previous study of the economic burden of HIV suggests that associated indirect costs may be more than 4 times the total direct medical expenses.36 Thus, cost increase outcomes presented in this study are highly conservative. Although opponents of MC have suggested that it may cause pain, decreased sexual pleasure, impaired sexual function, and psychological consequences,58 these effects would be considered indirect nonmedical costs and were not considered in this analysis. Furthermore, postprocedure follow-up with trial participants and US studies have not supported the existence of these negative consequences.59–64

This model analyzed a limited set of MC-reduced infections, focusing exclusively on infant male UTIs and conditions demonstrated through randomized trials to be associated with MC. Observational studies conducted in the United States suggest that MC may also decrease the risk of phimosis,32,65 gonorrhea, nongonococcal urethritis, chlamydia,66 and urogenital mycoplasma,67 but potential cost savings from averting these conditions was not incorporated. The trial efficacy parameters incorporated here are also likely to underestimate true risk reduction, as demonstrated by even higher (67%–73%) reductions in HIV infection during long-term follow-up of male MC trial participants.57

Although there are multiple factors that contribute to a nation’s MC rate, it is likely that reductions in insurance coverage play a role in lowered MC rates.6 Thus, the financial and health implications of policies that affect MC are substantial. Furthermore, a closer examination of MC rates, STI incidence, and the demographic characteristics of Medicaid beneficiaries suggests that the sub-populations likely to qualify for Medicaid also have the lowest rates of MC and the highest infection incidence.6 Therefore, decreased Medicaid coverage of MC may further exaggerate racial and socioeconomic disparities. Although this analysis has not explicitly evaluated the impact of reduced MC rates on such disparities, predictions based on this model’s outcomes and the heterogeneous distribution of infection burden and MC prevalence are concerning, and further study may be warranted. It is imperative to consider these results and their implications in establishing future health care policies related to MC.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr Tobian was supported by grant 1K23AI093152-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinician Scientist Development Award (#22006.02). Dr Gaydos was supported by grants HPTN U-01 AI068613 and U-54EB007958 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Author Contributions: All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kacker, Frick, Gaydos, and Tobian.

Acquisition of data: Kacker, Gaydos, and Tobian.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kacker, Frick, Gaydos, and Tobian.

Drafting of the manuscript: Kacker, Gaydos, and Tobian.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kacker, Frick, Gaydos, and Tobian.

Statistical analysis: Kacker and Frick.

Administrative, technical, and material support: Kacker, Gaydos, and Tobian.

Study supervision: Tobian.

References

- 1.Tobian AA, Gray RH. The medical benefits of male circumcision. JAMA. 2011;306 (13):1479–1480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu F, Markowitz LE, Sternberg MR, Aral SO. Prevalence of circumcision and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in men in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2004. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(7):479–484. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000253335.41841.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sansom SL, Prabhu VS, Hutchinson AB, et al. Cost-effectiveness of newborn circumcision in reducing lifetime HIV risk among U.S. males. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark SJ, Kilmarx PH, Kretsinger K. Coverage of newborn and adult male circumcision varies among public and private US payers despite health benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(12):2355–2361. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Trends in in-hospital newborn male circumcision—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(34):1167–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibowitz AA, Desmond K, Belin T. Determinants and policy implications of male circumcision in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(1):138–145. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.134403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dave SS, Fenton KA, Mercer CH, Erens B, Wellings K, Johnson AM. Male circumcision in Britain: findings from a national probability sample survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):499–500. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisch M, Friis S, Kjaer SK, Melbye M. Falling incidence of penis cancer in an uncircumcised population (Denmark 1943–90) BMJ. 1995;311(7018):1471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7018.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Male Circumcision: Global Trends and Determinants of Prevalence, Safety, and Acceptability. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auvert B, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Cutler E, et al. Effect of male circumcision on the prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus in young men: results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(1):14–19. doi: 10.1086/595566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray RH, Serwadda D, Kong X, et al. Male circumcision decreases acquisition and increases clearance of high-risk human papillomavirus in HIV-negative men: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(10):1455–1462. doi: 10.1086/652184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1298–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobian AA, Kong X, Gravitt PE, et al. Male circumcision and anatomic sites of penile high-risk human papillomavirus in Rakai, Uganda. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(12):2970–2975. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners’ genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(1):42.-e1–42.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wawer MJ, Tobian AA, Kigozi G, et al. Effect of circumcision of HIV-negative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):209–218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61967-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner L, Ghanem KG, Newman DR, Macaluso M, Sullivan PS, Erbelding EJ. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection among heterosexual African American men attending Baltimore sexually transmitted disease clinics. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(1):59–65. doi: 10.1086/595569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielson CM, Schiaffino MK, Dunne EF, Salemi JL, Giuliano AR. Associations between male anogenital human papillomavirus infection and circumcision by anatomic site sampled and lifetime number of female sex partners. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(1):7–13. doi: 10.1086/595567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobian AA, Gray RH, Quinn TC. Male circumcision for the prevention of acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections: the case for neonatal circumcision. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):78–84. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larke N, Thomas SL, Dos Santos Silva I, Weiss HA. Male circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(9):1375–1390. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoen EJ, Colby CJ, Ray GT. Newborn circumcision decreases incidence and costs of urinary tract infections during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 1):789–793. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 1999;103(3):686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiswell TE, Smith FR, Bass JW. Decreased incidence of urinary tract infections in circumcised male infants. Pediatrics. 1985;75(5):901–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chesson HW, Gift TL, Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Tao G, Johnson AP, Kent CK. A brief review of the estimated economic burden of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: inflation-adjusted updates of previously published cost studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(10):889–891. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318223be77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(4):322–338. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobian AA, Ssempijja V, Kigozi G, et al. Incident HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among men in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2009;23(12):1589–1594. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobian AAR, Charvat B, Ssempijja V, et al. Factors associated with the prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among men in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(7):945–949. doi: 10.1086/597074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold M. Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Med Care. 1996;34(12 suppl):DS197–DS199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss HA, Larke N, Halperin D, Schenker I. Complications of circumcision in male neonates, infants, and children: a systematic review. BMC Urol. 2010;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoen EJ, Colby CJ, To TT. Cost analysis of neonatal circumcision in a large health maintenance organization. J Urol. 2006;175(3 pt 1):1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00399-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Subpopulation estimates from the HIV incidence surveillance system—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(36):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schackman BR, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, et al. The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States. Med Care. 2006;44 (11):990–997. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228021.89490.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison KM, Song R, Zhang X. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):124–130. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b563e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutchinson AB, Farnham PG, Dean HD, et al. The economic burden of HIV in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: evidence of continuing racial and ethnic differences. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43 (4):451–457. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243090.32866.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen RY, Accortt NA, Westfall AO, et al. Distribution of health care expenditures for HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):1003–1010. doi: 10.1086/500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez BY, Barnholtz-Sloan J, German RR, et al. Burden of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 suppl):2883–2891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, Markowitz LE. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(2):244–251. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.070499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu D, Goldie S. The economic burden of noncervical human papillomavirus disease in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):500.e1–500.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JJ, Goldie SJ. Cost effectiveness analysis of including boys in a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in the United States. BMJ. 2009;339:b3884. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Kigozi G. The role of male circumcision in the prevention of human papillomavirus and HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199 (1):1–3. doi: 10.1086/595568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armstrong GL, Schillinger J, Markowitz L, et al. Incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(9):912–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chesson HW, Blandford JM, Gift TL, Tao G, Irwin KL. The estimated direct medical cost of sexually transmitted diseases among American youth, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):11–19. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.11.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):114–120. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000247627.84791.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001–2004: associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(11):864–869. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074e565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carr PL, Rothberg MB, Friedman RH, Felsenstein D, Pliskin JS. “Shotgun” versus sequential testing: cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for vaginitis. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):793–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marrazzo JM. Evolving issues in understanding and treating bacterial vaginosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2004;2(6):913–922. doi: 10.1586/14789072.2.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11):1478–1486. doi: 10.1086/503780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Tejani MN, Gift TL, Kent CK, Tao G. Estimates of the direct cost per case and overall burden of trichomoniasis for the employer-sponsored privately insured women population in the United States, 2001 to 2005. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(6):395–399. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318199d5fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gray RH, Wawer MJ. Reassessing the hypothesis on STI control for HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;371(9630):2064–2065. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60896-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bachmann LH, Hobbs MM, Sena AC, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis genital infections: progress and challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(suppl 3):S160–S172. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH. Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1674–1684. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisman DN. Projection of the future dimensions and costs of the genital herpes simplex type 2 epidemic in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(10):608–622. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2010. Atlanta, GA: Dept of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):853–858. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.049353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gray R, Kigozi G, Kong X, et al. The effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention and effects on risk behaviors in a posttrial follow-up study. AIDS. 2012;26(5):609–615. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283504a3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morris BJ, Bailey RC, Klausner JD, et al. Review: a critical evaluation of arguments opposing male circumcision for HIV prevention in developed countries. AIDS Care. 2012 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.661836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kigozi G, Lukabwe I, Kagaayi J, et al. Sexual satisfaction of women partners of circumcised men in a randomized trial of male circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. BJU Int. 2009;104(11):1698–1701. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kigozi G, Watya S, Polis CB, et al. The effect of male circumcision on sexual satisfaction and function, results from a randomized trial of male circumcision for human immunodeficiency virus prevention, Rakai, Uganda. BJU Int. 2008;101(1):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kigozi G, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, et al. The safety of adult male circumcision in HIV-infected and uninfected men in Rakai, Uganda. PLoS Med. 2008;5(6):e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gray R, Kigozi G, Kong X, et al. The effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention and effects on risk behaviors in a posttrial follow-up study. AIDS. 2012;26(5):609–615. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283504a3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morris BJ, Waskett JH, Banerjee J, et al. A ‘snip’ in time: what is the best age to circumcise? BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krieger JN, Mehta SD, Bailey RC, et al. Adult male circumcision: effects on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Kisumu, Kenya. J Sex Med. 2008;5(11):2610–2622. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morris BJ, Gray RH, Castellsague X, et al. The strong protective effect of circumcision against cancer of the penis. Adv Urol. 2011:812368. doi: 10.1155/2011/812368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alanis MC, Lucidi RS. Neonatal circumcision: a review of the world’s oldest and most controversial operation. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59(5):379–395. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200405000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mehta SD, Gaydos C, Maclean I, et al. The effect of medical male circumcision on urogenital Mycoplasma genitalium among men in Kisumu, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(4):276–280. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318240189c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]