Abstract

Background

Whether myocardial perfusion grade (MPG) following late recanalization of infarct-related arteries (IRA) predicts left ventricular (LV) function recovery beyond the acute phase of myocardial infarction (MI) is unknown.

Methods and Results

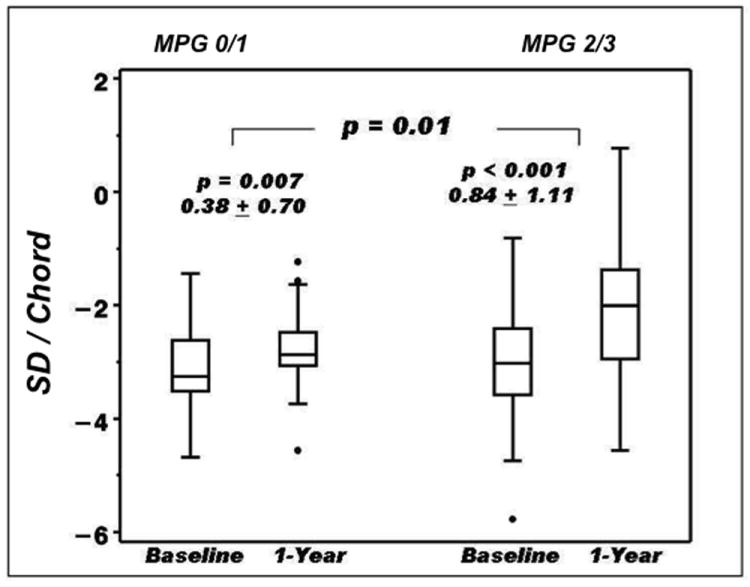

The Total Occlusion Study of Canada-2 (TOSCA-2) enrolled stable patients with persistently occluded IRA beyond 24 h and up to 28 days post-MI. We studied the relationship between the initial MPG and changes in LV function and volume, and the change in MPG from immediate post-PCI to one year in 139 PCI patients with TIMI 3 epicardial flow post PCI and with paired values, grouped into impaired or good MPG groups (MPG 0/1 or MPG 2/3). MPG 0/1 patients were more likely to have received thrombolytic therapy and to have a LAD IRA. They had lower blood pressure and LV ejection fraction (LVEF), and a higher heart rate and systolic sphericity index at baseline. Changes in the MPG 0/1 and MPG 2/3 groups from baseline to 1 year were: LVEF 3.3±9.0 and 4.8±8.9 percent (p=0.42), LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) -1.1±9.2 and -4.7±12.3 ml/m2 (p=0.25), LV end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVI) 0.08±19.1 and -2.4±22.2 ml/m2 (p=0.67), and standard deviations /chord for infarct zone wall motion index (WMI)) 0.38±0.70 and 0.84±1.11 (p=0.01). By covariate-adjusted analysis, post-PCI MPG 0/1 predicted lower WMI (p<0.001), lower LVEF (p<0.001) and higher LVESVI (p<0.01), but not LVEDVI at one year. Of the MPG 0/1 patients, 60% were MPG 2 or 3 at one year.

Conclusions

Preserved MPG is present in a high proportion of patients following late PCI of occluded IRAs post-MI. Poor MPG post-PCI frequently improves MPG over 1 year. MPG graded after IRA recanalization undertaken days to weeks post MI is associated with LV recovery indicating that MPG determined in the subacute post-MI period remains a marker of viability.

Keywords: acute coronary syndromes, myocardial infarction, myocardial perfusion, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery disease

Timely recanalization and sustained patency of the infarct related artery (IRA) are major determinants of left ventricular (LV) function and survival after acute myocardial infarction (MI). Patients with normal epicardial flow in the IRA (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] grade 3) but reduced tissue level perfusion as quantified by TIMI Myocardial Perfusion Grade (MPG) immediately following acute reperfusion with fibrinolysis, primary or rescue PCI1 have longer ischemic times, larger infarcts, worse global and regional LV systolic function, and increased mortality2, 3. These observations suggest that MPG marks microvascular integrity and is thereby a surrogate for myocardial viability in the acute phase of MI4-7.

In contrast to the extensively documented benefit of early recanalization, routine late recanalization (beyond 24 hours) after symptom onset is not well supported by evidence8, 9, and is not guideline-recommended. Until recently late PCI for persistent occlusion has generally been performed on the basis of the late open artery hypothesis10. The extent to which effective microvascular reperfusion can be achieved by PCI performed after the acute phase, and whether it is followed by regional or global functional recovery of the left ventricle is unknown. The Occluded Artery Trial (OAT)9 was a multi-center randomized controlled trial that evaluated the benefit of PCI in addition to optimal medical therapy compared to optimal medical therapy alone in patients beyond the first 24 hours and up to 28 days after MI onset. The Total Occlusion Study of Canada (TOSCA)-2 was a NHLBI-funded angiographic ancillary study of OAT with co-primary end-points of infarct-related artery patency at 1 year and change in LVEF from baseline to 1 year.8 Paired coronary and LV angiograms were obtained at baseline and 1 year post-PCI (n=332), providing a unique opportunity to evaluate the association between myocardial perfusion grade (MPG) at baseline (following successful PCI) and global and regional functional recovery at one year follow-up, and to examine the stability of perfusion grade over time.

Methods

Study population

The primary results of TOSCA-28 as well as the study design11 and results9 of the parent OAT have been published. Inclusion criteria for TOSCA-2 and OAT included a documented index MI and an occluded infarct-related artery (TIMI Flow Grade 0 or 1) in addition to one of two high-risk criteria – proximal occlusion or LVEF less than 50%. Important exclusion criteria included a clinical indication for revascularization (significant angina, severe inducible ischemia, left main or triple vessel disease), serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dl, severe valvular disease, New York Heart Association Class III or IV heart failure or cardiogenic shock at the time of screening. Inclusion criteria for the MPG analysis included OAT treatment assignment to the PCI group with subsequent successful PCI of IRA with post-PCI antegrade TIMI 3 flow. Finally, baseline, post-PCI and 1-year follow-up coronary angiograms suitable for MPG analysis and analyzable LV angiograms were also required.

Data collection

Baseline characteristics were recorded from the time of index MI to the time of randomization. Qualifying coronary and LV angiograms performed after the first 24 hours and up to 28 days post-MI, as well as post-PCI and follow-up angiograms performed after 1 year were submitted for quantitative analysis performed in a dedicated core angiographic laboratory. LV volumes, LVEF, regional wall motion and sphericity index were calculated as described previously12-14.

PCI

Protocol PCI of the IRA with routine stenting was performed within 24 hours of randomization. All patients received aspirin and either ticlopidine or clopidogrel beginning the day of the procedure or earlier. Anticoagulation with heparin during PCI to a target Activated Clotting Time of ≥250 seconds was recommended. Use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was encouraged.

Myocardial Perfusion Grading

The MPG substudy was prospectively planned and participating centers were instructed with respect to technique for obtaining immediate post-PCI and one year follow-up angiograms optimized for MPG analysis, generally requiring a longer cine-angiographic recording focusing on the myocardial segment likely to demonstrate blush. MPG was graded semi-quantitatively by two independent core lab readers (VJ, TS) trained to use standard TIMI MPG criteria1 and blinded to clinical data and timing, and sequence of angiography. In case of discrepancies, angiograms were re-read independently by both readers and any remaining discrepancies were resolved by a third reader (GBJM). Post-PCI and follow-up angiograms were also evaluated for residual thrombus and evidence of distal embolization. The present analysis was limited to patients with post-PCI TIMI Flow Grade 3 since it is technically difficult to grade myocardial blush when the epicardial vessel is poorly opacified and, moreover, abnormalities of MPG might no longer reflect microvascular function if flow were restricted proximally. We have recently published a reproducibility study including the TIMI MPG method in an angiographic core laboratory where we found a high degree of inter-observer reproducibility when MPG was dichotomized to 0 or 1 vs. 2 or 315. Due to the relatively small number of patients in this study and the inherent difficulties in MPG grading we therefore prospectively defined grouping of MPG to 0 or 1 (MPG 0/1) versus 2 or 3 (MPG 2/3).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were compared using Chi -square test or alternatively, Fisher’s exact test if expected frequency for any cell in a 2×2 table was <5. Wilcoxon Two-Sample test was used to compare time intervals from index MI to baseline angiography, randomization and PCI. Independent sample t-test was used to compare other continuous variables that were normally distributed. Within group changes over time were compared using a paired t-test of the difference and between group differences were compared with two sample t-tests. The pre-specified level of significance for all secondary analyses of OAT was p<0.01, while p≥0.01 and <0.05 was considered to indicate a trend toward statistical significance.

Effects of impaired post PCI MPG (MPG 0/1) on one year ejection fraction, wall motion, LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) and LV end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVI) were examined in an unadjusted as well as covariate adjusted linear regression model. All baseline covariates that were tested for are listed in Table 1 in the main OAT publication9. Adjustments were made for other baseline covariates with p < 0.05 on multiple linear regression using backward elimination. WMI was adjusted for baseline WMI, days to randomization, BMI and new Q waves. LVEF was adjusted for baseline LVEF, heart rate, BMI and new Q waves. LVESVI was adjusted for baseline LVESVI, no family history, NYHA > 1 at presentation and LAD as the IRA.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics by post-PCI MPG

| Characteristic | Post-PCI MPG 0/1 N= 33 | Post-PCI MPG 2/3 N= 124 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 78.8 | 85.5 | 0.350 |

| Age yrs, mean (SD) | 54.6 (9.2) | 57.4 (10.5) | 0.174 |

| Body mass index | 28.6±4.5 | 27.6±4.1 | 0.21 |

| Diabetes, % | 24.2 | 16.9 | 0.336 |

| Hypertension, % | 48.5 | 50.8 | 0.813 |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 48.5 | 58.9 | 0.285 |

| Family history of CAD, % | 42.4 | 48.4 | 0.542 |

| Current smoker, % | 42.4 | 31.5 | 0.236 |

| Prior angina, % | 12.1 | 21.8 | 0.216 |

| Prior MI, % | 6.1 | 13.7 | 0.368 |

| Interval from MI to baseline angiogram (days), median (IQR) | 5 (4, 8) | 5 (3, 9) | 0.566 |

| Interval from MI to randomization (days), median (IQR) | 9 (5, 17) | 10 (6, 20) | 0.512 |

| Interval from MI to PCI (days), median (IQR) | 10 (5, 18) | 10 (7, 20) | 0.507 |

| Interval from baseline angiogram to PCI (days), median (IQR) | 3 (0, 9) | 2 (0, 12) | 0.939 |

| Heart rate beats/min, mean (SD) | 74.9 (12.1) | 67.4 (10.9) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure mmHg, mean (SD) | 108.4 (16.5) | 119.3 (15.1) | 0.0004 |

| Diastolic blood pressure mmHg, mean (SD) | 66.9 (9.7) | 72.1 (10.8) | 0.014 |

| Fibrinolytic therapy during first 24 hr of index MI (%) | 45.4 | 16.9 | <0.001 |

| ST elevation >0.1mV, % | 72.7 | 59.8 | 0.175 |

| ST depression > 0.1 mV, % | 36.4 | 30.3 | 0.508 |

| New Q waves, % | 63.4 | 65.3 | 0.860 |

| Maximum pre-PCI Total CK divided by ULN, mean (SD) | 10.1 (6.2) (n=27) | 7.1 (7.3) (n=104) | 0.048 |

| Maximum pre-PCI CK MB divided by ULN, mean (SD) | 23.4 (26.6) | 11.8 (14.3) | 0.123 |

| Maximum pre-PCI TNI divided by ULN, mean (SD) | 172.4 (152.0) | 271.4 (713.6) | 0.253 |

| Maximum pre-PCI TNT divided by ULN, mean (SD) | 229.5 (215.9) | 50.6 (50.3) | 0.138 |

| Killip Class > 1 during index MI,% | 9.1 | 10.5 | 0.999 |

| NYHA Class > 1 at randomization,% | 9.1 | 6.4 | 0.700 |

Abbreviations PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, MPG: Myocardial Perfusion Grade, SD: standard deviation, CAD: coronary artery disease, MI: myocardial infarction, IQR (interquartile range), ULN: upper limit of the local laboratory normal, CK: creatine kinase, TNI: troponin I, TNT: troponin T

Results

Distribution of MPG

Of the 381 patients enrolled in TOSCA-2, 195 were assigned to PCI, and of these 186 had angiograms potentially suitable for baseline MPG analysis. The nine angiograms that were excluded had too short cine-angiographic recordings for analysis. The distribution of post-PCI TIMI Flow Grade in these 186 patients was: Grade 0 in 12 (6.5%), Grade 1 in 6 (3.2%), Grade 2 in 11 (5.9%) and Grade 3 in 157 (84.4%) patients. MPG, evaluated in all 157 patients with TIMI Flow Grade 3, was distributed as follows: MPG 0 in 25 (15.9%), MPG 1 in 8 (5.1%), MPG 2 in 77 (49.0%) and MPG 3 in 47 (29.9%). Baseline clinical characteristics of the MPG 0/1 and MPG 2/3 groups are provided in Table 1, angiographic and procedural characteristics in Table 2. Of these 157 evaluable patients, 142 also had MPG and global and regional left ventricular functional parameters suitable for analysis at 1-year follow up. Paired analyses were available for 139 patients (post-PCI and 1 year).

Table 2.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics by post-PCI MPG

| Post-PCI MPG 0/1 N = 33 | Post-PCI MPG 2/3 N = 124 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-PCI coronary angiography | |||

| IRA – LAD, % | 54.6 | 21.8 | <0.001 |

| IRA – Circumflex, % | 21.2 | 9.7 | |

| IRA – RCA, % | 24.2 | 68.5 | |

| IRA TIMI Flow Grade 0 to 1, % | 100.0 | 98.4 | 1.000 |

| Collaterals present, % | 72.3 | 95.1 | <0.001 |

| Single vessel disease, % | 87.9 | 81.4 | 0.385 |

| Pre-PCI left ventricular angiography | |||

| Infarct Segment Regional WMI SD/Chord, mean (SD) | -3.2 (0.7) | -2.9 (1.0) | 0.177 |

| LVEF, mean (SD) | 42.6 (11.6) | 50.6 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| LVESVI, mean (SD) | 39.8 (20.1) | 31.3 (14.3) | 0.08 |

| LVEDVI, mean (SD) | 69.7 (27.3) | 63.6 (24.7) | 0.34 |

| Diastolic Sphericity Index, mean (SD) | 31.0 (5.3) | 30.8 (6.4) | 0.862 |

| Systolic Sphericity Index, mean (SD) | 25.3 (6.1) | 22.9 (5.5) | 0.035 |

| Mitral Regurgitation present, % | 28.1 | 35.8 | 0.414 |

| Procedural characteristics and post-PCI angiography | |||

| Residual thrombus (%) | 9.1 | 2.4 | 0.108 |

| Distal embolization n (%) | 3.0 | 8.9 | 0.462 |

| Post-PCI residual % diameter stenosis, mean, (SD) | 29.8 (17.6) | 27.8 (14.3) | 0.507 |

| Post-PCI Minimal Luminal Diameter mm, mean, (SD) | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.5) | 0.097 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors used (%) | 90.9 | 83.1 | 0.27 |

| Stent implanted, % | 100.0 | 99.2 | 1.000 |

Abbreviations IRA: infarct-related artery, LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery, RCA: right coronary artery, TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, WMI: wall motion index, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, LVESVI: left ventricular end-systolic volume index, LVEDVI: left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Univariate correlates of impaired MPG post PCI

At baseline, patients with MPG 0/1 had evidence of larger infarcts, lower systolic blood pressure and LVEF, and a trend to a larger LVESVI and higher peak CK, compared to patients with MPG 2/3. They were also more likely to have an occluded LAD and to have been treated with fibrinolytic therapy for the index MI, and were less likely to have angiographically visible collaterals. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used in a majority of cases with no difference between groups. (Tables 1 and 2). These baseline findings are similar to those reported for the larger cohort of 261 OAT ancillary study patients in whom baseline MPG was measured16.

Optimal Medical Treatment

Both MPG groups had high rates of optimal medical therapy during hospital stay, at discharge and at one year follow-up, with no differences observed between the groups. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Utilization of Medical Therapies at discharge and at 1 year (by MPG)

| Discharge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPG 0/1 (N=30) | MPG 2/3 (N=109) | p-value | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Aspirin | 29 | 96.7 | 108 | 99.1 | 0.39 |

| Thienopyridines (clopidogrel or ticlopidine) | 30 | 100.0 | 108 | 99.1 | 1.00 |

| Aspirin or thienopyridine | 30 | 100.0 | 109 | 100.0 | NA |

| Aspirin plus thienopyridine | 29 | 96.7 | 107 | 98.2 | 0.52 |

| Warfarin | 5 | 16.7 | 4 | 3.7 | 0.02 |

| One or more of ASA, warfarin, thienopyridine | 30 | 100.0 | 109 | 100.0 | NA |

| Two or more of ASA, warfarin, thienopyridine | 30 | 100.0 | 107 | 98.2 | 1.00 |

| B-blocker | 28 | 93.3 | 97 | 89.0 | 0.73 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 29 | 96.7 | 94 | 86.2 | 0.19 |

| Spironolactone | 4 | 13.3 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.02 |

| Lipid lowering agent | 28 | 93.3 | 92 | 84.4 | 0.37 |

| 1 year | |||||

| 1 Year MPG 0 or 1 (N=29) | 1 Year MPG 2 or 3 (N=106) | p-value | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Aspirin | 28 | 96.6 | 100 | 94.3 | 1.00 |

| Thienopyridine (clopidogrel)* | 9 | 31.0 | 29 | 27.4 | 0.70 |

| Aspirin or thienopyridine | 28 | 96.6 | 103 | 97.2 | 1.00 |

| Aspirin plus thienopyridine | 9 | 31.0 | 26 | 24.5 | 0.48 |

| B-blocker | 28 | 96.6 | 89 | 84.0 | 0.12 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 28 | 96.6 | 92 | 86.8 | 0.19 |

| Spironolactone | 4 | 13.8 | 6 | 5.7 | 0.22 |

| Lipid lowering agent | 28 | 96.6 | 93 | 87.7 | 0.30 |

Changes in LV size and function over one year

As a group, patients with MPG 2/3 showed significant improvement at follow-up in measures of global contractility, including LVEF and LVESVI. In contrast, those with MPG 0/1 showed no improvement. The more demanding between-group comparison testing for differential effects of post-PCI MPG upon these LV parameters was not, however, significant (Figure 1A, 1B). Regional contractility of the infarct zone as expressed by the wall motion score improved in both MPG groups at follow-up, but the degree of wall motion improvement observed in the MPG 2/3 group was significantly greater than that observed in the MPG 0/1 group (Figure 1D). No significant change or difference was noted within or between MPG groups for LVEDVI (Figure 1C). We also observed significantly lower Systolic Sphericity Index at one year in the MPG 2/3 versus 0/1 groups (0.206 vs. 0.240, p=0.008).

Figure 1.

Comparison of baseline (post PCI) and follow-up at 1 year of (A) LVEF. (B) LVESVI (End Systolic index), (C) LVEDVI and (D) Target region wall motion (SD / chord) between groups (MPG 0/1 vs. MPG 2/3). Paired data. Values are given for change within group and p-values for within group and between groups comparison.

Changes in MPG over one year

Of the 109 MPG 2/3 group patients, 18 (17%) had MPG 0 or 1 at one year (Table 4). Binary restenosis in the IRA was observed in 16 of these patients (88.9%) and in 27 of 91 patients (29.7%) in whom MPG remained 2 or 3 (p<0.0001). Mean diameter stenosis was 82.5±22.8 vs. 43.9±20.4% (p<0.0001) in these two groups. Of the post-PCI MPG 0/1 group, 60% had MPG 2 or 3 at one year. Amongst the 30 MPG 0/1 patients with angiographic follow-up, restenosis was observed in 9 of the 18 (50%) with MPG 2 or 3 at one year, and 3 of 12 (25%) with persistent MPG 0 or 1 (p=0.17).

Table 4.

Changes in MPG over one year

| One-Year MPG | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-PCI MPG | MPG 0 or 1 | MPG 2 or 3 | Total |

| MPG 0/1 | 12 (40%) | 18 (60%) | 30 (22%) |

| MPG 2/3 | 18 (17%) | 91 (83%) | 109 (78%) |

| Total | 30 (22%) | 109 (78%) | 139 (100%) |

P value for changes is 0.006

Independent correlates of LV size and function at one year (by post PCI MPG)

On multivariable analysis (Table 5) post PCI MPG 0/1 predicted lower WMI (p=0.0002) and LVEF (p=0.0008), and a higher LVESVI (p=0.0056) at 1 year.

Table 5.

Effects of post-PCI MPG 0/1 vs. post-PCI MPG 2/3 on LV outcome measures at 1 year

| Variable | Unadjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate | SEM | T value | P value | |

| Infarct Segment Regional WMI (n=118) | -0.67 | 0.23 | -2.90 | 0.0045 |

| LVEF (n=126) | -8.86 | 1.92 | -4.60 | <0.0001 |

| LVESVI (n=76) | 7.23 | 3.14 | 2.30 | 0.023 |

| LVEDVI (n=76) | 4.66 | 5.34 | 0.87 | 0.39 |

| Covariate adjusted | ||||

| Infarct Segment Regional WMI | -0.71 | 0.18 | -3.89 | 0.0002 |

| LVEF | -5.75 | 1.67 | -3.43 | 0.0008 |

| LVESVI | 7.16 | 2.50 | 2.86 | 0.0056 |

| LVEDVI | 4.49 | 4.81 | 0.93 | 0.35 |

WMI adjusted for baseline WMI, days to randomization, BMI and new Q waves.

LVEF adjusted for baseline EF%, heart rate, BMI and new Q waves.

LVESVI adjusted for baseline LVESVI, no family history, NYHA >I, and LAD culprit.

LVEDVI adjusted for baseline LVEDVI, baseline LVEF, and LAD culprit

Discussion

This study addresses the ability of MPG to discriminate amongst patients with successful PCI of occluded infarct arteries, those who will have favorable changes in LV function from those who will not. To our knowledge this is the first study addressing the association between MPG and global and regional recovery of LV function following late recanalization of the IRA after MI, and also the first study to describe MPG at 1-year follow-up.

The study population was uniformly selected, and uniquely suited to test MPG as a predictor of LV recovery post-MI. OAT enrolled stable patients with occluded IRAs who underwent recanalization with PCI/stent. We selected only patients with normal epicardial flow immediately post PCI, after a median occlusion time of 10 days. Notably 79% of our cohort demonstrated MPG 2/3. Extending the results of studies examining acute reperfusion cohorts, preserved MPG was significantly associated with better indices of LV systolic function at 1 year (Figure 1). We also observed that MPG improved significantly from post PCI to follow-up at one year.

Distribution of MPG

Our results are consistent with a large study of early recanalization by primary PCI with good epicardial and microvascular flow in 1190 of 1548 patients (76.9%)17. In a recent publication on thrombus aspiration in the setting of acute MI, 75 to 82% of patients had myocardial blush grade 2 or 318. These two studies both used myocardial blush grade17 which, while employing somewhat different criteria, is angiographically and conceptually similar to the MPG system we used. The results are comparable to the 79% prevalence following successful late recanalization after the first 24 hours and up to 28 days post MI in the present study.

Several factors may be responsible for the high rates of preserved MPG following late PCI in the present study. We selected only patients with TIMI 3 flow post-PCI, as explained in the methods section. Stents were implanted in nearly all patients (99.4%) and angiographic evidence of residual thrombus and distal embolization was seen only in a very small number of patients. Finally, the myocardial edema and microvascular plugging by aggregates of leukocytes and platelets, typical of AMI may have begun to resolve in many of our patients. Rochitte and colleagues19 showed that the extent of microvascular obstruction increases over the first 48 hours after experimental acute myocardial infarction and reperfusion in canines. The same group reported that the peak extent of microvascular obstruction occurs two days after reperfusion and is unchanged at nine days20. Hozumi and co-workers21, using coronary Doppler ultrasound, reported short deceleration time of diastolic flow velocity (DDT), a measure of microvascular resistance, one day after IRA recanalization, indicating poor runoff in the microcirculation. Interestingly they found significantly longer DDT, indicating lower microvascular resistance, one and two weeks after acute IRA recanalization, both in a group with viable and a group with non-viable myocardium in the region of interest. In both groups the DDT normalized by two weeks after recanalization. The authors postulated that after the first two days following reperfusion there is a gradual recanalization of the occluded microvessels, causing a progressive decrease in coronary resistance, even in areas without viable myocardium. In support of this we observed an increase in the number of patients showing MPG 2 or 3 at 1 year compared to post-PCI. In light of these data it seems clear that poor blush can improve, indicating it does not always imply irreversible necrosis of the microvasculature even if the subtended myocardium is substantially infarcted. The change in MPG from good to worse is associated with severe restenosis in the IRA, suggesting that parts of the microcirculation in areas with scar tissue may occlude spontaneously over time in the presence of severe restenosis, even if the epicardial artery remains patent with TIMI 3 flow. Alternatively, assessment of MPG in the presence of a severe upstream stenosis, particularly in a previously infarcted region, may be unreliable.

Functional recovery in the context of TOSCA-2 results

In TOSCA-2, significant improvement in LVEF was observed at 1 year in both medically-treated, as well as PCI patients of about the same magnitude as in the MPG 2/3 group in our substudy (4.8±8.9%)8. The MPG 0/1 subgroup likely had more densely infarcted myocardium, and microvascular derangement as evidenced by the significantly lower LVEF and larger volumes just a few days post MI. As already stated, however, it does not appear that, if poor myocardial perfusion represents a larger infarct and microvascular derangement, that this derangement is entirely irreversible. In addition, improvement in LVEF appeared to be attenuated in the MPG 0/1 subgroup but was not significantly different from the MPG 2/3 subgroup. Also, the target regional wall motion score significantly increased in the MPG 0/1 group, which means there is some viability retained even with poor blush immediately post-PCI.

Rather, early poor perfusion may represent a larger extent of injury causing microvascular dysfunction and early ventricular dilation that has potential for recovery over time. This is further supported by the OAT nuclear ancillary study22 in which improvement in LVEF over 1 year was predicted by baseline infarct zone viability.

Infarct size and MPG

Patients with baseline clinical and angiographic features of larger infarct size subsequently exhibited impaired MPG following PCI in agreement with previous studies suggesting that infarct size is closely related to microvascular obstruction, despite restoration of epicardial patency23,24. Infarct size was shown to be a major determinant of reflow following release of coronary occlusion in an experimental model of coronary occlusion and recanalization24. We found fewer collaterals, significantly more LAD occlusions and a greater likelihood of unsuccessful fibrinolytic therapy in the MPG 0/1 group. These findings are similar to those reported for the larger cohort of 261 OAT ancillary study patients in whom baseline MPG was measured16 and in correspondence with data published by Kandzari et al.25 from a study of primary percutaneous revascularization in acute myocardial infarction, showing that anterior infarction is associated with greater impairment of LVEF, less frequent collateral flow and diminished reperfusion success as measured by MPG.

We reported in our previous publication16, that failed fibrinolytic therapy was significantly associated with impaired MPG following late recanalization of occluded IRAs by PCI. The association was no longer significant when adjusted for multiple variables that correlate with infarct size. This suggests that impaired post-PCI MPG in patients with failed fibrinolytic therapy is mainly related to larger infarct size and we may speculate that fibrinolytic therapy is preferentially administered to the more critically ill patients. Thus, the higher frequency of impaired MPG in patients suffering from LAD occlusion may be related to larger infarcts in these patients. Absence of collaterals, noted more often with LAD occlusion, may have further contributed to higher frequency of impaired MPG in this subset.

Limitations

Myocardial perfusion as assessed by contrast angiography is semi quantitative and might be considered a difficult parameter to adjudicate. We have, however, recently published a reproducibility study including the TIMI MPG method in an angiographic core laboratory15. We found a high degree of inter-observer reproducibility when MPG was dichotomized to 0 or 1 vs. 2 or 3. This is the main reason why we prospectively defined grouping of MPG to 0 or 1 versus 2 or 3. The study population in TOSCA 2 was relevant to examining the benefit of routine late PCI compared to medical therapy alone in patients with occluded infarct-related arteries post-MI and the results cannot be extrapolated to all patients undergoing late PCI after MI. We analyzed MPG only in the subset of this population with antegrade TIMI 3 flow post late IRA recanalization. Follow up coronary angiography may reflect ascertainment bias, with sicker patients not returning. Therefore it is unknown whether the reported findings in a subset of patients extend to the entire cohort.

Conclusion

Preserved MPG is present in the majority of MI survivors with normal epicardial flow following late PCI recanalization of their occluded infarct-related artery. Impaired baseline MPG is associated with unfavorable LV indices while preserved baseline MPG in our cohort is associated with segmental and global LV recovery. This observation extends prior analyses undertaken in acute MI settings and is consistent with favorable MPG marking retained viability within the infarct zone. Finally, those with poor baseline MPG frequently show MPG improvement and significantly, but modestly improved wall motion over 1 year, thus a relative lack of LV functional improvement. These data suggest that microvascular integrity and myocardial viability can be disengaged from one another in the chronic post-MI phase, and warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

The extent to which effective microvascular perfusion can be achieved by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) performed after the acute phase of a myocardial infarction (MI), and whether the magnitude of microvascular perfusion affects left ventriclar recovery (LV) is unknown. The Total Occlusion Study of Canada-2 (TOSCA-2), an ancillary study of the 2166-patient Occluded Artery Trial, enrolled 381 stable patients with persistently occluded infarct-related artery (IRA) days to weeks post-MI to PCI or medical therapy alone. Change in myocardial perfusion grade (MPG) was determined from immediate post-PCI to one year (157 patients) and the relationship between initial MPG and LV function and volume were assessed in 139 patients. Preserved MPG was present in the majority of patients with normal epicardial flow following late PCI recanalization of the IRA. Impaired baseline MPG was associated with unfavourable LV indices while preserved baseline MPG was associated with segmental and global LV recovery. Those with poor baseline MPG frequently showed MPG improvement and significantly, but only modestly improved wall motion over 1 year. Thus, microvascular integrity and myocardial viability can be disengaged from one another in the chronic post-MI phase, but subgroups of stable patients with areas of viable myocardium might benefit from late recanalization. Preserved MPG immediately post-PCI may be associated with LV recovery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the investigators and the staff at the study sites for their important contributions and Eunice Yeoh for her excellent work in the angiography core laboratory. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Harmony R. Reynolds for her editorial input on the manuscript, and Zubin Dastur and Emily Levy for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Sources of Funding

The project described was supported by Award Numbers U01HL062509, U01HL062511, R01 HL72906, and R01 HL75456 from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Džavík received research, honorarium and Advisory Board member funds from Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Advisory Board member funds from Abbott Vascular, and honoraria from Boston Scientific. Dr. Hochman received grant support to her institution from Eli Lilly and Bristol Myers Squibb Medical Imaging and product donation from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Schering-Plough, Guidant, and Merck for OAT and received consultation fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, honoraria for Steering Committee service from Eli Lilly and Glaxo Smith Kline and honoraria for serving on the Data Safety Monitoring Board of a trial supported by Schering-Plough.

References

- 1.Buller CE, Welsh RC, Westerhout CM, Webb JG, O’Neill B, Gallo R, Armstrong PW. Guideline adjudicated fibrinolytic failure: incidence, findings, and management in a contemporary clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Ryan KA, Mesley R, Marble SJ, McCabe CH, Van De Werf F, Braunwald E. Relationship of TIMI myocardial perfusion grade to mortality after administration of thrombolytic drugs. Circulation. 2000;101:125–130. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van ’t Hof AW, Liem A, Suryapranata H, Hoorntje JC, de Boer MJ, Zijlstra F. Angiographic assessment of myocardial reperfusion in patients treated with primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: myocardial blush grade. Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Circulation. 1998;97:2302–2306. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.23.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Luca G, van ’t Hof AW, de Boer MJ, Ottervanger JP, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, Dambrink JH, Zijlstra F, Suryapranata H. Time-to-treatment significantly affects the extent of ST-segment resolution and myocardial blush in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson CM, Murphy SA, Kirtane AJ, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Antman EM, Braunwald E. Association of duration of symptoms at presentation with angiographic and clinical outcomes after fibrinolytic therapy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:980–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, Ottervanger JP, de Boer MJ, van ’t Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, Suryapranata H. Incidence and clinical significance of distal embolization during primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1112–1117. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotani J, Mintz GS, Pregowski J, Kalinczuk L, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Suddath WO, Waksman R, Weissman NJ. Volumetric intravascular ultrasound evidence that distal embolization during acute infarct intervention contributes to inadequate myocardial perfusion grade. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:728–732. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00840-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dzavik V, Buller CE, Lamas GA, Rankin JM, Mancini GB, Cantor WJ, Carere RJ, Ross JR, Atchison D, Forman S, Thomas B, Buszman P, Vozzi C, Glanz A, Cohen EA, Meciar P, Devlin G, Mascette A, Sopko G, Knatterud GL, Hochman JS. Randomized trial of percutaneous coronary intervention for subacute infarct-related coronary artery occlusion to achieve long-term patency and improve ventricular function: the Total Occlusion Study of Canada (TOSCA)-2 trial. Circulation. 2006;114:2449–2457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Reynolds HR, Abramsky SJ, Forman S, Ruzyllo W, Maggioni AP, White H, Sadowski Z, Carvalho AC, Rankin JM, Renkin JP, Steg PG, Mascette AM, Sopko G, Pfisterer ME, Leor J, Fridrich V, Mark DB, Knatterud GL. Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355:2395–2407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochman JS, Choo H. Limitation of myocardial infarct expansion by reperfusion independent of myocardial salvage. Circulation. 1987;75:299–306. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Knatterud GL, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Mark DB, Reynolds HR, White HD. Design and methodology of the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) Am Heart J. 2005;150:627–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamas GA, Vaughan DE, Parisi AF, Pfeffer MA. Effects of left ventricular shape and captopril therapy on exercise capacity after anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandler H, Dodge HT. The use of single plane angiocardiograms for the calculation of left ventricular volume in man. Am Heart J. 1968;75:325–334. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(68)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheehan FH, Bolson EL, Dodge HT, Mathey DG, Schofer J, Woo HW. Advantages and applications of the centerline method for characterizing regional ventricular function. Circulation. 1986;74:293–305. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steigen TK, Claudio C, Abbott D, Schulzer M, Burton J, Tymchak W, Buller CE, John Mancini GB. Angiographic core laboratory reproducibility analyses: implications for planning clinical trials using coronary angiography and left ventriculography end-points. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging. 2008;24:453–462. doi: 10.1007/s10554-007-9285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorapur V, Steigen TK, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Webb JG, Strauss BH, Yeoh EE, Kurray P, Sokalski L, Machado MC, Kronsberg SS, Lamas GA, Hochman JS, Mancini GB. Distribution and determinants of myocardial perfusion grade following late mechanical recanalization of occluded infarct-related arteries postmyocardial infarction: A report from the occluded artery trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:783–789. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Luca G, van ’t Hof AW, Ottervanger JP, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, Dambrink JH, Zijlstra F, de Boer MJ, Suryapranata H. Unsuccessful reperfusion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Am Heart J. 2005;150:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svilaas T, Vlaar PJ, van der Horst IC, Diercks GF, de Smet BJ, van den Heuvel AF, Anthonio RL, Jessurun GA, Tan ES, Suurmeijer AJ, Zijlstra F. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The New England journal of Medicine. 2008;358:557–567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rochitte CE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Reeder SB, McVeigh ER, Furuta T, Becker LC, Melin JA. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;98:1006–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hozumi T, Kanzaki Y, Ueda Y, Yamamuro A, Takagi T, Akasaka T, Homma S, Yoshida K, Yoshikawa J. Coronary flow velocity analysis during short term follow up after coronary reperfusion: use of transthoracic Doppler echocardiography to predict regional wall motion recovery in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2003;89:1163–1168. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.10.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloner RA, Rude RE, Carlson N, Maroko PR, DeBoer LW, Braunwald E. Ultrastructural evidence of microvascular damage and myocardial cell injury after coronary artery occlusion: which comes first? Circulation. 1980;62:945–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.5.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Udelson JE, Pearte CA, Kimmelstiel CD, Kruk M, Teresinska A, Bychowiec B, Marin-Neto JA, Höchtl T, Cohen EA, Caramori P, Busz-Papiez B, Adlbrecht C, Sadowski ZP, Ruzyllo W, Forman SA, Kinan DJ, Lamas GA, Hochman JS. The Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) Viability Ancillary Study (OAT-NUC): Influence of Infarct Zone Viability on Left Ventricular Remodeling After PCI vs. Medical Therapy Alone. Circulation. 2007;116:II_624–II_625. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reffelmann T, Hale SL, Li G, Kloner RA. Relationship between no reflow and infarct size as influenced by the duration of ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H766–772. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00767.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarantini G, Cacciavillani L, Corbetti F, Ramondo A, Marra MP, Bacchiega E, Napodano M, Bilato C, Razzolini R, Iliceto S. Duration of ischemia is a major determinant of transmurality and severe microvascular obstruction after primary angioplasty: a study performed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1229–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandzari DE, Tcheng JE, Gersh BJ, Cox DA, Stuckey T, Turco M, Mehran R, Garcia E, Zimetbaum P, McGlaughlin MG, Lansky AJ, Constantini C, Grines CL, Stone GW for the CADILLAC Investigators. Relationship between infarct artery location, epicardial flow, and myocardial perfusion after primary percutaneous revascularization in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1288–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.