Abstract

HIV is frequently transmitted in the context of partners in a committed relationship, thus couples-focused HIV prevention interventions are a potentially promising modality for reducing infection. We conducted a systematic review of studies testing whether couples-focused behavioral prevention interventions reduce HIV transmission and risk behavior. We included studies using randomized controlled trial designs, quasi-randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized controlled studies. We searched five electronic databases and screened 7628 records. Six studies enrolling 1,084 couples met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Results across studies consistently indicated that couples-focused programs reduced unprotected sexual intercourse and increased condom use compared with control groups. However, studies were heterogeneous in population, type of intervention, comparison groups, and outcomes measures, and so meta-analysis to calculate pooled effects was inappropriate. Although couples-based approaches to HIV prevention appear initially promising, additional research is necessary to build a stronger theoretical and methodological basis for couples-based HIV prevention, and future interventions must pay closer attention to homosexual couples, adolescents and young people in relationships.

Sexual transmission of HIV occurs frequently in the context of a primary relationship between two consenting partners. However, HIV prevention interventions generally focus on individuals at risk, rather than specifying couples as a unit of change and analysis, neglecting the potentially crucial role that partners may play in sexual behavior (Allen et al., 2003; Painter 2001). Underpinning the dominant interventional focus on the individual, HIV prevention tends to be based on theoretical models emphasizing individual determinants of sexual risk behavior, such as the AIDS Risk Reduction Model (Catania et al.,1990), Health Belief Model (Becker, 1974), Information-Motivation-Behavior Model (Fisher & Fisher, 2002), and Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen, Albarracin, & Hornik, 2007). These approaches generally focus on the role of cognitive and motivational processes that operate at the level of the individual such as self-efficacy, personal beliefs and intentions, and perceived norms toward condoms (Albarracin et al., 2005). Interpersonal dynamics between partners tend to be overlooked in HIV prevention models. However, examining the broader literature on partner influences in health behavior demonstrates that partners and accompanying relationship factors need to be included in how we conceptualize health behavior change (House et al., 1988; Lewis et al., 2006). This may be especially relevant with regard to HIV-related sexual behaviors.

There is a growing consensus that HIV prevention research should address couples as a unit of behavior change and intervention (Harman & Amico, 2008). Earlier studies provided preliminary evidence for the feasibility of couples-based interventions for HIV—particularly the role of couples-based voluntary counseling and testing (Allen et al., 1992; Higgins et al., 1991; Padian et al., 1993). Moving beyond the context of HIV testing and counseling, more general couples-focused HIV prevention programs may differ from individual-focused HIV prevention programs by addressing the ongoing dynamic and interactional forces within dyads that contribute to sexual risk behavior, including gender roles, power imbalances, communication styles, child-bearing intentions, and quality of relationship issues (e.g., commitment, satisfaction, intimacy). Optimal modes for delivering couples-focused HIV prevention programs may differ from modes for intervening with individuals, for example by including couples counseling and exercises that involve both members of the dyad. Other couples-focused programs might involve simultaneously including both dyad members, or might address each member separately and alone, or might involve a combination of both modalities. Evaluation of couples-focused HIV prevention programs might also differ from individual-focused programs, for example by evaluating patterns of sexual behavior within the dyad, disaggregating sexual behavior with primary versus secondary partners, and deriving a composite measure of couple-level risk using an algorithm based on each partners’ individual behavior within and outside the relationship.

Although couples-based HIV prevention interventions have been promoted as a potentially promising strategy, there exists no known synthesis of the research on the effectiveness of these programs. Based on a comprehensive literature search of all high-quality evaluations of couples-focused HIV prevention programs, the aims of this paper were to (a) describe and synthesize findings from identified studies, and (b) conduct a critical analysis of the state of this research.

METHODS

Inclusion criteria

This review included any trials reporting evidence from prospective comparative evaluations of couple-focused interventions for the behavioural prevention of HIV, and which involved or attempted to involve both members of a self-identified couple. A couple was defined here as a dyad (two-person pair) involved in an intimate sexual relationship; length of relationship and depth of emotional commitment was unspecified in our search, and was left to be determined by primary study investigators. Studies could involve couples from anywhere in the world. Our a priori outcomes of interest were reduced biological indication of HIV or STI infection or reduced sexual risk behaviour in the intervention versus the control group. We included studies measuring any biological outcomes (e.g. HIV incidence, STI incidence, pregnancy) or behavioral outcomes (e.g. unprotected vaginal, oral, or anal sex, sharing of needles) as relevant markers of HIV risk. Studies that did not report either a biological or a behavioral outcome were excluded.

We included any randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-randomized controlled trials, and nonrandomized controlled studies of couples-focused interventions compared to any control group, in which participants were assigned to study groups and in which control group outcomes were measured concurrently with intervention group outcomes. Programs did not need to administer treatment to both dyad members together and concurrently; however we excluded trials of interventions that targeted just one individual in a couple.

No exclusions were made by control group condition (e.g. usual care, another HIV prevention intervention, no treatment, an attention-matched treatment, a different version of the experimental program) or by demographic characteristics, sexual orientation, HIV status, seroconcordance, or other factors. However, studies were excluded if the control did not involve a different type of intervention, such as studies in which the same intervention was administered to different populations. Additionally there were no exclusions by setting, timing, dosage, program activities or organization delivering the intervention.

Literature search

Electronic searches of AIDSLINE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, PsycINFO and PubMed from 1980 onward were carried out by reviewers in April 2007, and searches of the International AIDS Society Abstract Archive from 2000 to 2006 were also conducted. In addition, existing reviews and primary studies were cross-referenced for further citations and we searched for unpublished literature and ongoing trials by contacting experts and active researchers in the field. The search included terms specific to HIV/AIDS, study design (e.g., control, comparative), and intervention focus (for example, including search terms “couple,” “dyad,” “marital,” “married”; the full search strategy is available from study authors). Although there were no linguistic or geographic search restrictions, articles were excluded if there was insufficient information available in English to interpret the study.

All articles were initially screened by three reviewers to exclude records that were not clearly relevant. Reviewers received training on the initial screening criteria using a small subset of abstracts to ensure that they reached a high (>95%) level of agreement, after which they independently screened the remaining abstracts. Reviewers were encouraged to apply a more liberal approach to the initial abstract screening, to allow for a more stringent screening based on review of the full text. Reviewers were not blind to the identities of study authors, funding, or any other characteristic of the primary studies. Complete texts of all potentially relevant articles were retrieved and scrutinized by two reviewers who read each study and decided on conceptual and methodological relevance by consensus. All reviewers approved the final list of included studies. Study authors were contacted to clarify trial details as needed.

Data extraction

Reviewers extracted data including details about study design, participants, interventions delivered to the intervention and control groups, method of data collection, baseline differences, attrition, analytic procedures and treatment effects. Where data was reported on cost, harms, acceptability and program implementation (i.e., program design, actual delivery by clinicians, actual uptake by participants, and context), this was also extracted. If the search retrieved multiple reports of any evaluation, data were extracted from all available reports.

Analysis and assessment of study quality

Our overarching aim was to summarize the state of evidence on effectiveness of couples-focused HIV prevention interventions, with a secondary aim of assessing the quality of existing studies. Provided there was reasonable methodological justification for pooling results across studies, meta-analysis would have been a statistical technique for summarizing the effect size across trials. But if meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate (e.g., due to heterogeneity among study designs, outcomes, intervention processes), we aimed to provide a narrative summary and critical analysis.

We assessed the following aspects of study quality:

Study design (RCT, quasi-RCT, quasi-experimental study)

Method of allocating participants to trial arms

Concealment of allocation sequence from trial staff and from personnel who recruit participants into the trial (for RCTs)

Blinding of participants, program staff, and outcome assessors (we do not expect most studies in this field to blind participants and/or facilitators, as preliminary research suggests that these interventions often involve time and personal contact)

Baseline differences between trial arms, methods of controlling for differences in analyses

Attrition: percentage dropout at each follow-up, differential attrition between trial arms, and differences between dropouts and participants who are retained

Method of outcome assessment (e.g., ACASI, biomarkers, self-report)

Analytic procedures: Intention to treat, complete case, per-protocol, or treatment-on-the-treated.

We did not make any exclusions due to study quality, but instead report these aspects of methodological quality in the review.

RESULTS

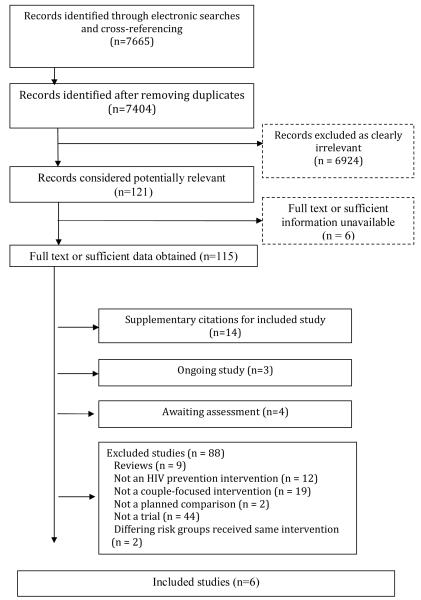

The electronic database searches initially retrieved 7628 records (56 from AIDSLINE, 374 from CENTRAL, 919 from CINAHL, 927 from PsycINFO and 5352 from PubMed). Cross-referencing retrieved an additional 37 records. After the removal of duplicate references in Endnote, 7404 unique records were screened. Of these, 121 records were deemed relevant by any reviewer and marked for full-text retrieval. There was insufficient information available in English to interpret three studies and despite efforts to contact authors it proved impossible to obtain sufficient information to determine the inclusion of three other studies. Of the 115 papers retrieved, 14 were supplementary citations for included studies, 3 referred to ongoing studies and 4 studies were still awaiting assessment, their authors having been contacted for missing statistical and descriptive data. Four studies that initially appeared to meet inclusion criteria were later excluded. Two of these reported couple focused interventions, however, neither were prospective comparative trials (Allen et al., 1992 and Parsons et al., 2000). Two further studies were excluded since they described differing risk groups that received the same intervention; Allen and colleagues (2003) compared HIV+ discordant couples to couples who were HIV-concordant, while Kissinger and colleagues (2003) compared HIV+ couples with those who had syphilis. Eighty-four further studies were excluded for reasons specified in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies

Description of included studies

Six studies published between 2000 and 2007 reporting couple-focussed behavioural interventions for HIV were included in this review (see Table 1 for characteristics of included studies). These studies ranged in size from 26 index couples (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2007) to a three-center trial including 586 index couples (Coates et al., 2000). Three studies were carried out in the United States (El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005; Harvey et al., 2004; Koniak-Griffin et al., 2007) while two took place in Africa (Farquhar et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2005), with one further study conducted in sites in Africa and the Caribbean (Coates et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Summary of 6 included studies

| Author | Location, year | Primary intervention aim | Study design | Comparison | Method of allocation; Sample size |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria |

Primary outcome measures |

Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coates et al., 2000 | Kenya, Tanzania and Trinidad, 1995 to 1998 |

To determine efficacy of HIV Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) in reducing unprotected intercourse among individuals and sex partner couples |

Randomised controlled trial |

Individuals or couple participants randomly assigned to HIV VCT or basic health information |

Random allocation Index Couples, n = 589; Index Individuals, n = 1563; Couples Education, n = 584; Individual Education, n = 1557 |

|

|

|

| El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005 | Bronx, New York, 1997 to 2001 |

To assess efficacy of relationship-based HIV and STD prevention provided to couples or women alone |

Randomised controlled trial |

Compared intervention when delivered to couples together versus to women alone, with education-only individual control group |

Random allocation; Index Couples, n = 81; Women alone, n = 73; Education, n = 63 couples |

|

Three primary outcomes assessed for past 90 days:

|

|

| Farquhar et al., 2003 |

Nairobi, Kenya, Sept 2001 to Dec 2002 |

To assess the impact of partner HIV VCT involvement (specifically being counselled as a couple) on perinatal intervention uptake and condom use |

Prospective cohort study |

HIV VCT delivered to couples compared to individuals |

Based on preference: women and men were post-test counselled individually or as a couple Couples, n = 116; Individuals, n = 192 |

Women were enrolled while attending their first antenatal visit; no information on exclusion criteria |

|

|

| Harvey, et al., 2004 | Los Angeles, January 2002 to June 2002 |

To assess effectiveness of couples HIV risk reduction counselling on condom and contraceptive use and UI in Hispanic couples |

Randomised controlled trial |

Couples-based HIV/AIDS risk reduction intervention compared with couples-based educational standard of care |

Random allocation Index cases, n = 69; Controls, n = 77 |

Women eligible if

who were pregnant, intended to become pregnant within the next year, had ever used injection drugs or reported being HIV positive |

|

No differences between groups in

|

| Jones et al., 2005 | Zambia | To assess the influence of partner participation in cognitive behavioral single-sex group intervention on sexual risk behaviour among HIV positive Zambian women |

Cohort study with randomised sub-group |

Women whose partner received 4 sessions of the intervention were compared with those partners who received only one session |

Male partners randomly assigned to high or low intensity Female participants = 180 Male partners = 152 |

Women eligible if:

tested positive within past 2 weeks and if no sexual partner |

|

Female participants with partners in high intensity group reported:

|

| Koniak-Griffin, et al., 2007 |

Los Angeles, US. |

Evaluate a theory based, couple-focused HIV prevention intervention for inner-city Latino teen parenting couples |

Quasi- experimental |

12-hour couple focused HIV prevention program compared with brief HIV prevention |

Allocated to experimental or control condition based on site of recruitment Experimental couples = 26 Comparison couples = 23 |

Couples included if

|

|

|

Intervention design and content

Three studies used RCTs and 3 used quasi-experimental designs. One RCT (Harvey et al., 2004) compared a couples-focused HIV prevention intervention with a couples-focused community educational program. Another RCT (El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005) used a 3-arm design, comparing an HIV prevention intervention given to either couples or to female partners alone, in comparison with an education control condition comprising female partners alone. A third RCT (Coates et al., 2000) delivered HIV voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) to both individuals and to couples, and compared these treatment conditions to individuals or couples who received health information. In a quasi-experimental study, Koniak-Griffin et al., (2007) compared an enhanced couples-focused 12-hour HIV prevention program with a 1.5 hour didactic presentation providing standard information on HIV/AIDS. Jones et al. (2005) provided single gender group-based HIV prevention to women and randomly allocated their male partners to either a high or low intensity group HIV prevention intervention. Farquhar et al. (2003) compared those participants who wished to undergo HIV VCT individually versus those who chose to complete VCT with their partner.

Definition of “couple” varied between trials. Three trials (Coates et al., 2000; El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005; Harvey et al., 2004) included participants with a primary/main or regular sex partner (i.e. those with legal/common- law spouses or regular girl/boyfriends) whereas another defined couple relationships as ‘characterised by romantic/sexual intimacy’ (Koniak-Griffin 2007). Jones and colleagues (2005) simply encouraged participants to invite ‘their male partners’. In Farquhar et al. (2003) nearly all those who enrolled as couples had been married or living together for over 3 years; however, there was no explicit operational definition of a couple. Only two studies (,El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005; Koniak Griffin et al., 2007) specified length of relationship as part of their inclusion criteria (≥ 6 months and 3 months , respectively). Details of other specific inclusion and exclusion for participants in trials reviewed are reported in Table 1.

There was notable heterogeneity in intervention content. Couples-focused HIV VCT was evaluated in two separate interventions (Coates et al., 2000; Farquhar, et al., 2003). The intervention by El Bassel et al. (2003, 2005), provided to women with their partners or women alone, emphasized relationship context, gender roles, communication, and intimacy as contributors to unprotected sex. Jones et al. (2005) provided female participants with cognitive-behavioral skills training delivered in same-gender groups, and their partners were randomly assigned to a high or low intensity same-gender group HIV education intervention. The intervention by Harvey et al. (2004) provided Hispanic women and their male partners culturally appropriate counseling and facilitated discussions in small groups about relationship dynamics contributing to sexual risk behavior and choices about contraception. Koniak-Griffin et al. (2007) implemented a theory-based, culturally-sensitive couple focused intervention for adolescent mothers and their male partners which addressed HIV awareness, vulnerability to HIV infection, attitudes and beliefs about HIV and safer sex. Four interventions (Coates et al., 2000; Jones et al., 2005; Harvey et al., 2004; Koniak-Griffin et al., 2007) explicitly described including either condom skills or a condom demonstration, and four studies (Coates et al., 2000; Jones et al. 2005; Farquhar et al., 2003, Harvey et al., 2004) explicitly reported providing participants with free condoms.

Interventions were carried out by a variety of trained HIV prevention educators and health professionals. The number of intervention sessions delivered to participants also differed between studies. VCT interventions included both pre and post-test counselling and offered additional counselling sessions at follow-up. Other programs provided between 2 and 6 intervention sessions which were delivered over a range time periods. Follow-up assessments took place from 6 to 14 months after intervention.

Participant satisfaction with the intervention was described for three trials included in the review (El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005; Jones et al., 2005; Koniak Griffin et al., 2007), and were generally positive. Cost effectiveness was reported for only one trial (Coates et al. (2000). Implementation data, including delivery, was reported for three studies (Coates et al., 2000; El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005; Harvey et al., 2004).

Harms were described in two studies. In the Coates et al. (2000) trial, couple members who were assigned to receive couples-based HIV VCT reported a higher likelihood of being neglected or disowned by their families at the first follow-up, compared with couple members in the comparison group (in Grinstead et al., 2001). In Farquhar et al. (2004), partners of women who tested seronegative for HIV reported a lower rather than higher likelihood of condom use at post-test, ostensibly due to a belief that partners were in a seronegative concordant relationship.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies was variable. Only one of the three randomized controlled studies reported secure allocation concealment (Coates et al., 2000). Allocation concealment was compromised in one study (El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005) when it was discovered that a few random assignment allocation envelopes had been omitted accidentally. Harvey et al., (2004) reported that their method of group allocation was not blind. One further study (Jones 2005), where randomization was used to allocate partners to high or low intensity intervention, did not report their method of allocation. Given the nature of the interventions undertaken, it was impossible to blind participants or intervention providers to treatment conditions in any of the included trials. The remaining studies used quasi-experimental methodologies in which assignment to condition was not determined randomly, which might have permitted uncontrolled and unrecognized biases between treatment groups.

Summary of study findings

There was considerable heterogeneity among studies in terms of trial characteristics, participants included, intervention content, and behavioural and biological outcomes measured. As a result, meta-analysis was considered inappropriate.

All trials included in this review described outcomes on either unprotected/protected sex or sex with/without condoms as a behavioral indicator of program effect. However, the unit of analysis (couples or individuals), time intervals, type of sexual encounter (oral, vaginal or anal), and type of protection (male or female condom) reported varied between studies.

The most commonly described measure, episodes of unprotected/protected sex, was reported by four studies (El Bassel et al., 2003, 2005; Coates et al., 2000; Harvey et al., 2004; Koniak-Griffin et al., 2007). El Bassel and her colleagues (2003, 2005) reported a significant increase in protected sexual encounters in both enhanced treatment groups—couples-based and women alone—compared with the standard education condition, while Coates and his colleagues (2000) reported that couples assigned to VCT significantly reduced unprotected intercourse with enrolment partners compared with those assigned to the standard health information condition. Harvey et al. (2004) compared enhanced couples-focused counseling versus standard couples-focused education, and found no differences between the intervention and comparison group in condom use at 3 months, but did detect a significant difference (p < 0.001) between baseline and three month follow-up for both conditions. This lack of significant differences between the intervention and comparison groups prompted the authors to suggest that the couples-focused modality improved outcomes in both trial arms. Koniak-Griffin et al.(2007) found unprotected sex significantly reduced at six month evaluation in the treatment group compared with the comparison group (p < .001). Jones et al. (2005) found higher condom use among women whose partners received high intensity counseling (p < .05). Farquhar et al. (2003), reported a marginal increase (p = 0.07) in women reporting condom use after undergoing couple-counseling compared to individual counseling.

A variety of other behavioral outcomes, reflecting the differing primary aims of the studies, were reported (See Table 1). Coates et al. (2000) found that couples reduced unprotected intercourse with their enrollment partners, however found no differences in unprotected sex with non-enrolment partners. Farquhar et al. (2003) found that women counseled with their partners were more likely to receive nevirapine during follow-up and to avoid breast feeding their infants compared to women counseled individually. Harvey et al. (2004) found both treatment and control groups increased use of effective contraceptive methods.

Measures related to biological outcomes were described in two studies. Coates et al. (2000) detailed the incidence of STDs, reporting that unprotected intercourse with non-enrollment partners substantially increased risk for the acquisition of a sexually transmitted disease (p < 0.05). El Bassel et al. (2003) reported fewer mean STD symptoms among participants in the control group compared with those in either intervention groups, but this difference was eliminated after adjusting for baseline STDs. HIV serostatus was not reported as an outcome measure in any of the studies in this review.

DISCUSSION

This review included 6 evaluation studies of couples-focused behavioral interventions conducted in five countries—3 African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia), 1 Caribbean country (Trinidad), and the United States. Each of these studies showed that participation in couples-focused counseling and educational programs was associated with improvements in HIV prevention behaviors, generally indicated by reduced unprotected sex. Meta-analysis of pooled effects was not permissible due to study heterogeneity. However, examination of trends across studies indicates promising effects for HIV prevention programs that address couples and dyadic relationship issues.

Strengths of this review included a comprehensive search without restriction due to country, inclusion of only high-quality evaluations which used randomized or quasi-experimental designs, and assessment of study methodology. This is the first known systematic review of couples-focused HIV behavioral prevention interventions.

Due to our inability to compute an overall effect size for these interventions, this review cannot conclude whether couples-based HIV prevention interventions are more or equally effective as other common — and perhaps less complex — HIV prevention modalities supported in previous reviews, such as mass media interventions (Vidanapathirana, Abramson, Forbes, & Failey, 2006) and individual or small group programs for HIV prevention (Kelly & Kalichman, 2002). Notably, one systematic review of condom promotion interventions conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia found low evidence of post-intervention behavior change for people with primary partners and/or casual partners (Foss, Hossain, Vickerman, & Watts, 2007). Conclusions from that review highlight the need for developing innovative HIV prevention techniques that address dyadic and relationship dynamics that contribute to unprotected sex and other HIV risk behaviors.

Sources of heterogeneity should be noted. Studies varied in their operationalization of a “couple”, with some providing stringent criteria about relationship duration and living arrangements, and other studies allowing female participants to identify their male partner themselves. Intervention components differed substantially, with two studies evaluating couples-focused HIV VCT and the remainder evaluating educational and counseling programs which addressed HIV risk and sexual behavior in the context of a primary relationship. In addition, although the context of a primary relationship was considered, the intervention content varied in how much they focused on relationship dynamics. Although all studies involved testing an intervention addressing both members of the dyad, they varied in the extent of inclusion of male partners and in their modality of providing the intervention—either to both partners together, to each partner separately and individually, or to partners separately and in small same-gender groups. Furthermore, the sexual behavior outcomes were often only evaluated for women, and no study utilized dyadic data analytic techniques.

Notably, all studies included heterosexual couples. No interventions for homosexual couples were identified that met inclusion criteria. Also lacking were studies in Asia, South or Central America, Eastern Europe, and many African countries highly impacted by HIV. Study sites in the United States were restricted to Los Angeles and New York. Only one program for adolescent couples was identified (Koniak Griffin et al., 2007).

Limitations of this review may challenge the generalizability of findings. The lack of a shared definition of being a couple might have introduced additional variability across studies, and prevents conclusions about types of couples and other factors related to relationship status that might promote intervention effectiveness. Participants and couples included in these six studies might not be indicative of most couples and relationships in their respective settings. Many studies recruited women seeking health services as index participants, and these women referred their male partners to the study. Couples-focused intervention modalities might not be appropriate for couples in which male partners are less willing to take part, younger adolescent couples, same-sex couples, and couples outside of HIV epicenters. Specific active intervention ingredients and mechanisms of behaviour change were not specified for the included studies, and so it is not possible to describe the processes by which couples-focused interventions might reduce HIV risk. Finally, despite our systematic and comprehensive attempt to search the literature, this review might not have identified all relevant studies such as unpublished reports and non-English language papers.

Couples-focused approaches to HIV prevention are still in an early phase of development. Additional methodological and measurement advances are necessary to improve on the state of science for couples-focused HIV prevention. Future investigations of couples-focused to HIV prevention should utilize analytic techniques that illuminate dynamics both within and between couples (e.g., Actor Partner Independence Model; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), rather than comparing individual intervention participants to control participants. High-quality evaluations of programs are urgently needed for other populations, such as homosexual men and younger adolescents, and in both urban and rural settings in the developing world and the developed world. There have been examinations of the role of relationship factors in these populations (Lescano et al., 2006; Prestage et al., 2006), which suggest that contextual considerations such as intimacy are significantly associated with condom use. It is recommended that scientists in this topic area identify appropriate outcome measures for indicating behaviour change among partners within the couple context and with outside sex partners, in order to reduce measurement heterogeneity and to facilitate future meta-analysis.

Future couples-focused interventions for HIV prevention must be based on a stronger conceptual and theoretical understanding of the relationship dynamics that might contribute to sexual risk behaviors among couples, including gender roles, power, communication, intimacy, reproduction goals, family responsibilities, concurrent partners. These factors are likely to be culturally determined and tied to norms around gender and sexuality. For example, gendered relationship and family dynamics might pose barriers to enacting safer sex intentions in more traditional cultures, and norms in some same-sex or youth communities might support more frequent high risk sexual behaviors. Cultural and community normative beliefs and values may also differ in the extent to which individuals have multiple concurrent partners — i.e., having a primary partner in addition to non-primary or casual outside partners — which may substantially influence risk for HIV transmission within and outside the primary relationship dynamic. Indeed, concurrent partnerships have been posited to have contributed to the scale of the epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa and in homosexual communities (Gorbach & Holmes, 2003; Halperin & Epstein, 2004; Kalichman et al., 2007), as well as increased incidence of HIV in African Americans in the southern United States (Adimora et al., 2003). This suggests that future interventions may need to address the issue of communication about concurrent and/or outside partnerships within primary relationships, which would include communication about condom use. Thus, given the complex context of primary relationships, models of intervention must follow from a stronger understanding of couples and dyadic issues, rather than employ individual-focused models of health behaviour change and decision making which might be inappropriate for framing couples-focused HIV prevention programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Kristen Underhill for assistance in conducting the literature review, and all researchers and primary authors who responded to our requests for additional information. This research was supported by NIDA grant R01DA018621 to Dr. Don Operario, and NIMH grant K08MH072380 to Dr. Darbes.

REFERENCES

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fulliove RE. Concurrent partnerships among rural African Americans with recently reported heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;34:423–429. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Albarracin D, Hornik R. Prediction and change of helath behavior: Applying the Reasoned Action Approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Albarracin D, Gillette JC, Moon-Ho H, Early AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR. A test of major assumptions about behaviour change: A comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:865–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. BMJ. 1992;304:1605–1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, Zulu I, Trask S, Fideli U, Musonda R, Kasolo F, Gao F, Haworth A. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17:733–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. General Learning Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–473. [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM) Health Education and Behavior. 1990;17:53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Grinstead OA, Gregorich SE, Sweat MD, Kamenga MC, Sangiwa G, et al. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Hill J, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:963–969. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Hill J, Steinglass P. Long-Term effects of an HIV/STI sexual risk reduction intervention for heterosexual couples. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Kabura MN, John FN, Nduati RW, et al. Antenatal couple counseling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37:1620–1626. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model. In: DiClemente R, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. Jossey Bass Publishers; San Francisco, CA: 2002. pp. 40–70. [Google Scholar]

- Foss AM, Hossain M, Vickerman PT, Watts CH. A systematic review of published evidence on intervention impact on condom use in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:510–516. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach PM, Holmes KK. Transmission of STIs/HIV at the partnership level: Beyond individual-level analyses. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80(Suppl 3):15–25. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DT, Epstein H. Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa’s high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet. 2004;364:4–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmann JJ, Amico KR. The relationship-oriented information information-motivation-behavioral skills model: A multilevel structural equation model among dyads. AIDS and Behavior. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9350-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SM, Henderson JT, Thorburn S, Beckman LJ, Casillas A, Mendez L, et al. A randomized study of a pregnancy and disease prevention intervention for Hispanic couples. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:162–169. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.162.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DL, Galavotti C, O’Reilly KR, Schnell DJ, Moore M, Rugg D, Johnson R. Evidence for the effects of HIV antibody counseling and testing on risk behaviors. JAMA. 1991;266:2419–2429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Ross D, Weiss SM, Bhat G, Chitalu N. Influence of partner participation on sexual risk behavior reduction among HIV-positive Zambian women. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 4):92–100. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Ntseane D, Nthomang K, Segwabe M, Phorano O, Simbayi LC. Recent multiple sexual partners and HIV transmission risks among people living with HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:371–375. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Kalichman SC. Behavioral research in HIV/AIDS primary and secondary prevention: Recent advances and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:626–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL, Simpson JA. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger PJ, Niccolai LM, Magnus M, Farley TA, Maher JE, Richardson-Alston G, et al. Partner notification for HIV and syphilis: effects on sexual behaviors and relationship stability. Sexually Transmited Diseases. 2003;30:75–82. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Henneman T, Huang R, Huang X, Tello J, et al. HIV Prevention for Latino Adolescent Mothers and Their Partners. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0193945907310490. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescano CM, Vazquez EA, Brown LK, Litvin EB, Pugatch D, Project SHIELD Study Group Condom use with “casual” and “main” partners: what’s in a name? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:443. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11:365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padian NS, O’Brien TR, Chang Y, Glass S, Francis D. Prevention of heterosexual transmisión of human immunodeficiency virus through couple counseling. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1993;6:1043–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter TM. Voluntary counseling and testing for couples: A high-leverage intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;53:1397–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Huszti HC, Crudder SO, Rich L, Mendoza J. Maintenance of safer sexual behaviours: evaluation of a theory-based intervention for HIV seropositive men with haemophilia and their female partners. Haemophilia. 2000;6:181–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestage G, Mao L, McGuigan D, Crawford J, Kippax S, Kaldor J, Grulich AE. HIV risk and communication between regular partners in a cohort of HIV-negative gay men. AIDS Care. 2006;18:166–172. doi: 10.1080/09540120500358951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidanapathirana J, Abramson MJ, Forbes A, Fairley C. Mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing: Cochrane systematic review. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:233–234. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]