Abstract

Objective

The purposes of this analysis were to determine how select characteristics of nutritive sucking (number of sucks, sucks/burst, and sucks/minute) change over time and to examine the effect of select factors (morbidity, maturity, prefeeding behavior state, and feeding experience) on those changes.

Study design

A longitudinal, non-experimental study was conducted in a Level 3 neonatal intensive care unit using a convenience sample of 88 preterm infants. Statistical analyses were performed using a repeated-measures mixed-model in SAS.

Results

Sucking activity (number of sucks, sucks/burst, and sucks/minute) was predicted by morbidity, maturity, feeding experience and prefeeding behavior state. Experience at oral feeding had the greatest effect on changes in the number of sucks, suck/burst and sucks/minute.

Conclusion

Experience at feeding may result in more rapid maturation of sucking characteristics.

Keywords: infant feeding, prematurity, experience

Introduction

Despite improved survival of preterm infants, many common care issues remain, particularly when to initiate and advance oral feedings to achieve the best outcomes.1,2 One factor in the transition from gavage to oral feedings is the coordination of sucking with swallowing and breathing.3 Although sucking is generally considered a reflex behavior, it is also the mechanism involved in feeding over which the infant has any control. Thus, the maturation of sucking activity is of interest to those who monitor infants’ feeding skill development.

During nutritive sucking, two patterns of sucking are seen. Continuous sucking, which is more common at the beginning of a feeding, involves no interruptions for breathing and essentially represents a single, long suck burst.4,5 Intermittent sucking, which follows continuous sucking, involves interruptions for breathing. Although sucking does not automatically activate swallowing,3 it does influence the frequency of swallowing and thus, the interruption of airflow associated with swallowing. With preterm infants’ respiratory rates ranging between 40 and 60 breaths per minute, frequent swallowing can easily interfere with respiration. As the coordination of sucking with swallowing and breathing is not thought to occur before 34 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA),6 most preterm infants are fed orally before achieving coordination of these mechanisms. In fact, the American Academy of Pediatrics has included competency at oral-feeding, either breast or bottle, as a criterion for preterm infant readiness for hospital discharge;7 this guideline probably contributes to the incidence of earlier oral feeding initiation. Feeding before coordination occurs is possible because the infant learns to protect the airway either by alternating periods of prolonged respiratory pause during which vigorous sucking occurs with long breathing bursts, or by blocking the nipple with the tongue.8 Thus, preterm infants tend to suck, swallow and breathe in an alternate, rather than coordinated fashion.4,9 Despite these capabilities, the risks of feeding difficulty or adverse events during feeding are greater for preterm infants.10 To reduce these risks, understanding the maturation of sucking thus becomes important to facilitate oral feedings.

It is known that an infant’s medical condition11 and neurological maturity6,12 influence nutritive sucking. Behavior state has also been shown to have a relationship to sucking activity.13 There is now increased evidence that early experiences affect brain development and function in infants born preterm.14 However, the contribution of feeding experience to changes in nutritive sucking have rarely been examined.15–18

Protocols for advancing oral feedings based on the success of the previous feeding have been proposed.19 Infants fed using such protocols have attained full oral feeding earlier than infants not on protocol.16,20 In other studies, infants who had more opportunities to bottle feed consumed more of their prescribed formula by bottle and did so more efficiently independent of their ‘success’ at previous feedings.21 The underlying rationale for these latter findings may be related to the development of sucking activity that is associated with increased feeding opportunities. The purposes of this analysis were to determine how select characteristics of nutritive sucking (number of sucks, sucks/burst and sucks/minute) change over time and to examine the effect of select factors (morbidity, maturity, prefeeding behavior state and feeding experience) on those changes. The nutritive sucking characteristics chosen for study represent observable activity that have been associated with sucking maturation.22

Methods

A convenience sample of 95 preterm infants was recruited to this longitudinal, non-experimental study of feeding readiness in preterm infants. Data were collected over 3 years. Infants were eligible for the study if they were born <32 weeks PMA and had no known gastrointestinal, craniofacial, cardiovascular, neurological or muscular defects. Infants were observed at one feeding daily or every other day depending on morbidity for 10 to 14 observations. Observations included measures of morbidity, maturity and feeding experience as well as prefeeding behavior state and characteristics of sucking.

Sucking data were collected using a strain gage, which has established reliability as a measure of nutritive sucking.4,23 The strain gage was interfaced with a computerized data acquisition system, resulting in the production of waveform data that was visually examined for characteristics of sucking activity. Using parameters consistent with the literature, a suck was defined as any positive deflection from baseline that was of <1 s duration, with a suck burst defined as two or more sucks with 2 s between individual sucks.3 Morbidity was measured using the Neonatal Medical Index (NMI),24 which measures how ill infants are during the hospital stay. NMI scores at 32 weeks PMA are predictive of PMA at full bottle feedings.18 NMI classifications range from 1 to 5, with 1 describing preterm infants without serious medical problems and 5 describing infants with the most serious complications; birth weight but not gestation are factored into the scale. Maturity was measured using both PMA and day of life (DOL). Prefeeding behavior state (BS) was measured using the Anderson Behavior State Scale (ABSS).25 The ABSS measures sleep and wakefulness on a scale of 1 to 12, where 1 is deep sleep and 12 is hard crying. The scale has been used in many feeding studies.21,26 Consistent with other studies and numerous reports suggesting that a quiet alert state is optimal for preterm infant feeding,26 the ABSS observations were treated as interval data. Moreover, the data indicated that modeling behavior state as a linear trend alone would be problematic from a theoretical perspective, thus, both the linear and quadratic effects of behavior state were modeled. Feeding experience was defined as the number of cumulative oral feedings. This experience was not controlled in the study; rather, infants were offered oral feedings at the discretion of the staff, consistent with unit practice. Feeding experience data were recorded by data collectors at each observed feeding. Infants received formula or breast milk in a volume prescribed by the neonatologists; this amount varied across infants and increased for all infants over the course of the study, consistent with infants’ growth.

Ethics

The study was reviewed by the Institution’s Human Subject Review Board. Parents gave informed written consent.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed for each dependent variable using SAS (version 9.1. 3) proc mixed with an auto-regressive (AR(1)) covariance structure to model the dependency of observations within a subject across time. Model effects were tested for significance at alpha <.05; non-significant effects were removed from the model.

Results

The sample for this analysis consisted of 88 preterm infants; data from seven infants in the original sample of 95 were excluded because of insufficient sucking data. The remaining sample had PMA at birth ranging from 24 to 32 weeks (M=29.4 weeks) and birth weights ranging from 550 to 2390 g (M=1290 g, s.d.=397 g); all infants were appropriate weight for gestation. There were 43 male and 45 female infants; 61% of the samples were African American or black and 27% were White. A total of 711 feedings were included in the analysis. Infants began oral feeding between 1 and 61 days old (M=22, s.d.=14), between 32 and 35 weeks PMA (M=32.7 weeks, s.d.=0.6 weeks), and between 1055 and 2596 g (M=1575 g, s.d.=267 g).

The infant characteristics that were investigated for their effect on nutritive sucking were: morbidity (NMI at 32 weeks PMA); maturity at first bottle-feed (PMA, DOL, weight); prefeeding behavior state; and experience opportunities (average number of bottles per day). The sucking dependent variables were: number of sucks, sucks/burst and sucks/minute. As all of the dependent variables were skewed, the log-transformed values were used. This transformation yielded satisfactory approximation of normality and equal variance. Descriptive statistics for study variables at three intervals during the study protocol are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables

|

Early (n=81)a |

Middle (n=77)a |

Late (n=60)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | ||||

| Bottle days | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.84 | 6.83 | 6.68 | 6.99 | 13.80 | 13.54 | 14.06 |

| Day of life | 23.46 | 20.46 | 26.45 | 28.94 | 25.76 | 32.11 | 38.35 | 34.69 | 42.01 |

| PMA | 32.70 | 32.58 | 32.81 | 33.56 | 33.44 | 33.69 | 34.46 | 34.30 | 34.63 |

| Experience | 4.51 | 4.02 | 4.99 | 4.54 | 4.06 | 5.02 | 4.35 | 3.79 | 4.91 |

| Behavior State | 4.78 | 4.28 | 5.28 | 4.91 | 4.47 | 5.35 | 4.45 | 3.87 | 5.03 |

| Weight | 1565 | 1512 | 1618 | 1739 | 1677 | 1801 | 1899 | 1822 | 1976 |

| Number of sucks | 84.46 | 65.41 | 109.06 | 114.43 | 90.21 | 145.15 | 159.27 | 128.61 | 197.24 |

| Sucks/burst | 7.04 | 6.05 | 8.18 | 6.78 | 5.87 | 7.83 | 7.86 | 6.80 | 9.09 |

| Sucks/minute | 14.20 | 11.65 | 17.30 | 16.59 | 13.72 | 20.07 | 22.02 | 18.92 | 25.63 |

| Proficiencyb | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Efficiency | 1.88 | 1.50 | 2.27 | 2.57 | 2.08 | 3.07 | 3.57 | 2.98 | 4.17 |

| Consumedb | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.74 |

Abbreviations: PMA, post-menstrual age; CI, confidence interval.

Early=first observed feeding within the first 5 days, Middle=feeding closest to day 7 (and within days 5–9), Late=feeding closest to day 14 (and within day 12–16).

Expressed as a proportion.

The developmental trends in sucking behavior across time were of primary interest in this analysis and so the statistical analysis method took into account the dependencies due to repeated observations of the same infant. Thus, a repeated-measures mixed-model analysis was used with two groups of effects: effects modeling the changes in mean level of sucking behavior according to infant characteristics and effects modeling the trend across time of sucking behavior and how this trend varied according to infant characteristics. The following infant characteristics were included in the model: morbidity (four NMI groups, collapsing groups 1 and 2), maturity (PMA, day of life and weight at first oral feeding), experience (number of oral feedings per day over the 2 to 3 week study period) and behavior state (included as both a linear trend and quadratic trend). Time was modeled using the number of days since the first oral feeding. To assess differences in time-related trends, the following interactions with days of oral feeding were included in the model: NMI, initial weight, initial DOL, feeding experience.

Infants were grouped according to morbidity, day of life at first bottle-feeding and amount of feeding experience. Three, mutually exclusive subject groups were identified. The first was a steady group (N=31), which included the most well infants (n=12; NMI=1 or 2) who began bottle feeding on or before DOL 7, and the moderately ill infants (n=19; NMI=3) who began feeding on DOL 22 or later. The second was a fast group (N=11), which included only the most well infants (NMI=1 or 2) who began bottle feeding on DOL 8 or later. The third and largest group (n=46) was the moderates. This group was comprised of moderately ill infants (n=23; NMI=3), who began feeding on or before DOL 21, as well as more ill infants (n=23; NMI 4 or 5), including the most ill (n=12; NMI=5), who began feeding on or after DOL 22.

As seen in Table 2, the three groups described above were different in all three sucking characteristics. In addition, there were significant differences in sucking as the days of oral feeding increased. Moreover, the groups differed in trends across time for number of sucks and sucks/minute. There were also significant differences associated with initial weight, bottle-feeding experience and the behavior state observed during the feedings.

Table 2.

Effect of infant characteristics on nutritive sucking

| Effect |

Number of sucks

|

Sucks/burst |

Sucks/minute

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate a | s.e. | P-value | Estimate a | s.e. | P-value | Estimate a | s.e. | P-value | |

| Groups (NMI and DOL) b | — | — | 0.0427 | — | — | 0.0112 | — | — | 0.0311 |

| Steady | 4.0405 | 0.3141 | — | 2.0684 | 0.1300 | — | 2.7919 | 0.1488 | — |

| Moderate | 3.9214 | 0.2928 | — | 1.8841 | 0.1242 | — | 2.7021 | 0.1429 | — |

| Fast | 4.2718 | 0.3155 | — | 2.1529 | 0.1494 | — | 3.0081 | 0.1690 | — |

| Weight at first feedingc | 0.4216 | 0.1737 | 0.0174 | — | — | NS | — | — | NS |

| Experienced | 0.0635 | 0.0214 | 0.0039 | 0.0475 | 0.0160 | 0.0038 | 0.0679 | 0.0168 | 0.0001 |

| Behavior state (linear)e | −0.1057 | 0.0591 | 0.7450 | −0.1045 | 0.0390 | 0.9871 | −0.1144 | 0.0483 | 0.0181 |

| (Quadratic) | 0.0111 | 0.0054 | 0.0421 | 0.0105 | 0.0036 | 0.0037 | 0.0122 | 0.0044 | 0.0062 |

| Days of oral feeding f | — | — | <.0001 | 0.0116 | 0.0059 | 0.0506 | — | — | 0.0111 |

| Steadyg | 0.0062 | 0.0123 | 0.6163 | — | — | — | 0.0026 | 0.0101 | 0.7946 |

| Moderate | 0.0738 | 0.0110 | <.0001 | — | — | — | 0.0416 | 0.0091 | <.0001 |

| Fast | 0.0935 | 0.0283 | 0.0010 | — | — | — | 0.0459 | 0.0233 | 0.0493 |

Abbreviations: DOL, day of life; NMI, neonatal medical index; NS, nonsignificant.

All analyses used the log-transformed response; the fixed-effect parameter estimates of the repeated-measures analysis are on the log base e) scale. The parameter estimate and standard error of the estimate (s.e.) are given.

The P-value tests whether the groups were different (at day 7). As in most cases, there was a significant interaction (Groups×days), the days of oral feeding predictor variable was centered (at 7 days). Thus, the parameter estimates for the groups are the predicted values on day 7.

For convenience, weight at 1st feeding was divided by 1000 g so that the parameter estimate would reflect the trend per kilogram.

The parameter estimate for experience is the effect per number of cumulative oral feedings.

The 12-category ABSS was modeled as a second-degree trend. Thus, both linear and quadratic trends must be included in the model. The P-value for the quadratic trend is the test of interest.

The P-value for days of oral feeding tests whether the trajectory across time is different (see b), except in the case of sucks/burst where it tests whether the single trajectory within groups is zero.

The parameter estimates for days of oral feeding are shown separately for each group. And so, the P-value indicates whether the slope within the group is zero.

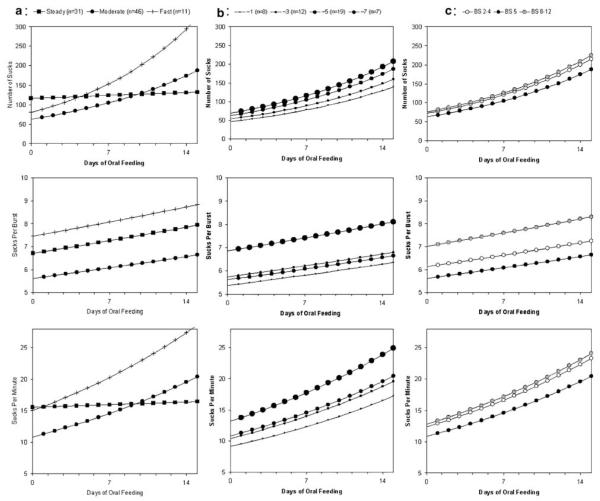

Figure 1 illustrates these effects. To discuss each of the effects more clearly, the figure shows the different trends across time, holding all other predictors constant. The description of the effects is provided in the following order: group effects (Figure 1a), experience effects (Figure 1b) and behavior state effects (Figure 1c). The rows in the figure show the effects of the predictors on the sucking characteristics from top to bottom: number of sucks, sucks/burst and sucks/minute.

Figure 1.

(a) Three infants groups identified by black squares (steady progression), black circles (moderate progression) and plus sign (fast increase). (b) Feeding experience groups identified by increasing circle size: smallest (approximately one bottle feeding per day), next largest (approximately three bottle feeding per day), next to the largest (approximately five bottle feedings per day) and the largest circle (approximately seven bottle feeding per day). (c) Behavior state identified by: open circle (sleep states), black circle (drowsy state) and gray circle (awake and active states).

The first row of panels shows the effects on the number of sucks during a feeding. The differential effect of the three infant groups on the number of sucks is shown in the top left-hand panel (Figure 1a), where the following factors are held constant: daily bottle feeding experiences (~5/day), behavior state (drowsy) and initial weight (>1500 g). The black squares are the steady group infants who show a very small increase in the number of sucks over time. These 31 infants suck, on average, 117 times on their very first bottle-feeding and after 2 weeks average 132 sucks during a feeding. The 46 infants in the moderate group, represented by the black circles, show a moderate increase in sucking. They begin with fewer sucks (63) than the steady group, but improve quickly and after 2 weeks average 188 sucks per feeding. The 11 infants represented by the plus sign show a fast increase. They begin at nearly the same number of sucks as the moderate group (80) but improve much more rapidly and after 2 weeks achieve an average of 323 sucks in a feeding.

The differential effect of feeding experience is shown in the middle panel (Figure 1b). Here, the following factors are held constant: group (moderate), behavior state (drowsy) and initial weight (>1500 g). The symbols show the effect of experience. The smallest circle represents those infants who received approximately one bottle-feeding opportunity per day. The next largest circle, received approximately three bottle-feeding opportunities per day. The next to the largest circle received approximately five bottle-feeding opportunities per day. Those infants receiving approximately seven bottle-feeding opportunities per day are shown with the largest circle. On day 14 the mean number of sucks for these four experience groups is 139, 160, 188 and 207, respectively. That is, the difference between infants who receive minimal experience and maximal experience is that they demonstrate an average of 68 more sucks during a feeding after 2 weeks; this is more than a minute longer of sucking.

The differential effect of the three behavior state groups is shown in the right-hand panel (Figure 1c), where the following factors are held constant: group (moderate), feeding experience (approximately five bottle-feeding opportunities per day) and weight (>1500 g). The open circle represents sleep states, the black circle represents the drowsy state and the gray circle represents awake and active states. The analysis indicated that there was a quadratic effect due to behavior state; as behavior increased from sleep to awake to active, the number of sucks did not increase linearly. Rather sucking had a minimum value at a drowsy state and was greater if the infant was either in a sleep or awake and active states. Specifically, at day 14 infants in a drowsy state sucked an average 188 times whereas infants in sleep states had more sucking activity at 215 sucks and infants in more awake and active states had even greater sucking activity with 225 sucks during the feeding.

The second row of panels illustrates the results for sucks/burst. The same factors are held constant and the symbols used represent the same groups as those described above. Again, sucks/burst increased with time but the trend is different depending upon the three subject groups. As seen in the middle panel, the moderate group had the fewest sucks/burst while the steady group’s rate was 1.3 sucks/burst greater. The fast group sucked at a rate 2.2 sucks/burst higher than the moderate group. In the middle panel on this row, it is clear that infants with the greatest experience (approximately seven feeding opportunities per day) had a higher sucking rate (1.5 sucks/burst). In the right panel, again the drowsy state has the lowest sucking rate, with infants in sleep states or awake and active states having more sucks/burst.

The results for sucks/minute are shown in the bottom panels of Figure 1. This rate increased steadily (P=0.0009) but the rate of increase varied between the three groups (P=0.0111). In the left panel, the steady group is seen to begin and end at approximately 16 sucks/minute; in fact, there is only a small increase over 2 weeks (0.91). The moderate group began with 11 sucks/minute, increased by 0.64 on each day and on day 14 had reached 21 sucks/minute. The fast group began at the same place as the steady group, but increased by 0.91 sucks per day and on day 14 had reached 29 sucks/minute. In the middle panel on this row, the effect of feeding experience is shown. Infants with the least experience increased their sucking rate the least, to 17 sucks/minute on day 14. The middle two experience groups attained 20 sucks/minute over the 14 days. Infants with the most experience increased their sucking rate the most and attained 25 sucks/minute by day 14. In the right panel on this row, the effect of behavior state is seen. Infants in the drowsy state have a lower sucking rate (20 sucks/minute at day 14) and infants in sleep states or awake and active states suck faster (approximately 24 sucks/minute).

Discussion

Successfully making the transition from gavage to oral feedings requires an infant to coordinate suck-swallow-breathe. There is increasing evidence that both the quantity and quality of bottle feeding experience may play a role in this feeding transition.16,20 However, the match between environmental experience and neurological expectation during critical periods of development has been shown to be increasingly important.27 Initiating oral feeding is often based on infant weight and PCA. Once oral feedings are initiated, a common but untested practice is gradually, but arbitrarily, to increase oral offerings over a period of time. Oral feeding attempts are often limited because of concerns that excess energy will be expended at the cost of weight gain, although this is not documented in the literature.28,29 Few studies have examined the effect of experience on feeding outcomes, including nutritive sucking.

The infant’s medical condition11 also influences the transition from gavage to full oral feedings. In particular, the already complex process of bottle-feeding is further complicated by illness severity, or morbidity in preterm infants. Morbidity has been found to account for 12% of the variance in PCA at first bottle feeding and 42% of the variance in PCA at full bottle feedings.18 Morbidity has also been correlated with sucking pressures in preterm infants, although not with sucking organization.30 Preterm infants with complications have been shown to have fewer sucks and fewer suck bursts at discharge than less severely ill preterm infants.31–33 Ventilator support is particularly related to delays in achievement of feeding milestones,34 with the number of days on oxygen being the strongest predictor of bottle feeding initiation and feeding ability.35

At the same time, neurological maturity is also needed for successful oral feeding.1 Although swallowing and sucking have been observed in utero as early as 13 and 18 weeks gestation, respectively, coordination usually does not occur before 32 to 34 weeks.36 Coordination of sucking and swallowing with breathing occurs even later, at 37 weeks of gestation37 and is indicative of neurodevelopmental maturation. Preterm infants generally move through several stages of feeding, beginning with gavage and progressing over time to either breast or bottle feeding.38 These stages are more often based on traditional practice rather than on empirical evidence.39 Most neonatal centers initiate bottle feedings before suck-swallow-breathe coordination is present. So, although the ‘transition time’ from gavage to bottle feeding has decreased significantly over the last 10 years,40 it is unlikely that this decrease represents a more rapid maturation of skills needed for bottle feeding. Rather, it probably indicates that age is only a general parameter for successful achievement of this developmental milestone.

In this analysis of sucking data from 88 subjects, we found that sucking activity (number of sucks, sucks/burst and sucks/minute) was predicted by morbidity, maturity, experience at feeding and prefeeding behavior state. In particular, experience at oral feeding had the greatest effect on characteristics of sucking. There are currently no empirically derived guidelines for either starting or progressing oral feedings for preterm infants. The rate at which feedings should be progressed is a particularly difficult clinical issue that is, unfortunately, often managed by arbitrary rules or by trial and error. That is, the number of oral feedings a day may be increased by one or two every day or every other day even though there is no evidence to support the effectiveness of this pattern. Alternatively, the decision about when to offer an oral feeding rather than give the feeding by gavage may be left to the discretion of the bedside caregiver, usually a nurse. Although nurses report using criteria for these decisions,41 research has also shown that there is little evidence that documentation of these unsystematic decisions exist.17 The analysis presented here presents strong evidence that preterm infants should be offered more frequent opportunities to feed orally.

In this analysis, we were looking for trends in nutritive sucking characteristics across time. There is increasing evidence that both the quantity and quality of oral feeding experience may play a role in the feeding transition.16,20,21 Further research is required to more completely explore the effect of experience on feeding skill development. A randomized clinical trial using the significant predictors reported here, morbidity, maturity and feeding experience as factors, is recommended, with infants randomly assigned to feeding experience groups stratified by morbidity and maturity. Outcomes similar to those measured here as well as clinical outcomes such as weight gain, days to full oral feeding and days to discharge, could be considered. Clinical trials of this nature will provide the only unbiased evidence upon which to base future practice related to the initiation and progression of oral feedings for preterm infants.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, R01 NR005182.

References

- 1.McGrath JM, Bodea Braescu AV. State of the science: Feeding readiness in the preterm infant. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2004;18:353–368. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thoyre SM, Brown RL. Factors contributing to preterm infant engagement during bottle-feeding. Nurs Res. 2004;53:304–313. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau C, Schanler RJ. Oral motor function in the neonate. Clin Perinatol. 1996;23:161–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickler RH, Reyna BA. Effects of nonnutritive sucking on nutritive sucking, breathing, and behavior during bottle feedings of preterm infants. Adv Neonat Care. 2004;4:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiao SY. Comparison of continuous versus intermittent sucking in very-low-birth-weight infants. JOGN Nurs. 1997;26:313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizuno K. The maturation and coordination of sucking, swallowing, and respiration in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2003;142:36–40. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.mpd0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 1998;102:411–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koenig JS, Davies AM, Thach BT. Coordination of breathing, sucking, and swallowing during bottle feedings in human infants. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:1623–1629. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.5.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathew OP, Bhatia J. Sucking and breathing patterns during breast- and bottle-feeding in term neonates. Effects of nutrient delivery and composition. Am J Di Child. 1989;143:588–592. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150170090030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemons PK. From gavage to oral feedings: Just a matter of time. Neonatal Netw. 2001;20(3):7–14. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.20.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rommel N, De Meyer A-E, Feenstra L, Veereman-Wauters G. The complexity of feeding problems in 700 infants and young children presenting to a tertiary care institution. J Pediat Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:75–84. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medoff-Cooper B, Bilker W, Kaplan M. Suckling behavior as a function of gestational age: A cross-sectional study. Infant Behav Dev. 2001;24:84–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medoff-Cooper B, Ratcliffe SJ. Development of preterm infants: feeding behaviors and brazelton neonatal behavioral assessment scale at 40 and 44 weeks’ postconceptional age. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2005;28:356–363. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Als H, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Rivkin MJ, Vajapeyam S, Mulkeren RV, et al. Early experiences alters brain function and structure. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):846–857. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fucile S, Gisel E, Lau C. Oral stimulation accelerates the transition from tube to oral feeding in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2002;141:230–236. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson C, Schanler RJ, Lau C. Early introduction of oral feeding in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2002;110:517–522. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickler RH, Reyna BA. A descriptive study of bottle feeding opportunities in preterm infants. Adv Neonat Care. 2003;3:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s1536-0903(03)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickler RH, Mauck AG, Geldmaker B. Bottle-feeding histories of preterm infants. JOGN Nurs. 1997;26:414–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCain GC. An evidence-based guideline for introducting oral feeding to health preterm infants. Neonatal Netw. 2003;22(5):45–50. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.22.5.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCain GC, Gartside P, Greenberg JM, Lott JW. A feeding protocol for healthy preterm infants that shortens time to oral feeding. J Pediatr. 2001;139:374–379. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickler RH, Best AM, Reyna BA, Wetzel PA, Gutcher GR. Prediction of feeding performance in preterm infants. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2005;5:116–123. doi: 10.1053/j.nainr.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medoff-Cooper B, McGrath JM, Bilker W. Nutritive sucking and neurobehavioral development in preterm infants from 34 weeks PCA to term. MCN, Am J Mat Child Nurs. 2000;25(2):64–70. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.deMonterice D, Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Crichton CL, Mangurten HH. Concurrent validity of a new instrument for measuring nutritive sucking in preterm infants. Nurs Res. 1992;41:342–346. Dowling. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korner AF, Stevenson DK, Kraemer HC, Spiker D, Scott DT, Constantinou J, et al. Prediction of the development of low birth weight preterm infants by a new neonatal medical index. J Dev Behavioral Pediatr. 1993;14:106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill NE, Behnke M, Conlon M, Anderson GC. Nonnutritive sucking modulates behavioral state for preterm infants before feeding. Scand J Caring Sci. 1992;6:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1992.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCain GC, Gartside P. Behavioral responses of preterm infants to a standard-care and semi-demand feeding protocol. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2002;2:187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas A, Chess S. The Dynamics of Psychological Development. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1980. Early life experience and its developmental significance; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collinge JM, Bradley K, Perks C, Rezny A, Topping P. Demand vs scheduled feedings for premature infants. JOGN Nurs. 1982;11:362–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1982.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pridham K, Kosorok MR, Greer F, Kayata S, Bhattacharya A, Grunwald PC. Comparison of caloric intake and weight outcomes of an ad lib feeding regimen for preterm infants in two nurseries. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:751–759. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medoff-Cooper B, Gennaro S. The correlation of sucking behaviors and Bayley Scales of Infant Development at six months of age in VLBW infants. Nurs Res. 1996;45:291–296. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bazyk S. Factors associated with the transition to oral feeding in infants fed by nasogastric tubes. Am J Occup Ther. 1990;44(12):1070–1078. doi: 10.5014/ajot.44.12.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandich MB, Ritchie SK, Mullett M. Transition times to oral feeding in premature infants with and without apnea. JOGN Nurs. 1996;25:771–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medoff-Cooper B, McGrath JM, Shults J. Feeding patterns of full term and preterm infants at forty weeks post-conceptional age. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:231–235. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200208000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bier JA, Ferguson A, Cho C, Oh W, Vohr BR. The oral motor development of low-birth-weight infants who underwent orotracheal intubation during the neonatal period. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:858–862. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160320060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker PT, Grunwald PC, Moorman J, Stuhr S. Effects of developmental care on behavioral organization in very-low-birth-weight infants. Nurs Res. 1993;42:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bu’Lock F, Woolridge MW, Baum JD. Development of co-ordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing: Ultrasound study of term and preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32:669–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1990.tb08427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathew OP. Respiratory control during nipple feeding in preterm infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1988;5:220–224. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders RB, Friedman CB, Stramoski PR. Feeding preterm infants. Schedule or demand? JOGN Nurs. 1991;20:212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1991.tb02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau C, Alagugurusamy R, Schanler RJ, Smith EO, Shulman RJ. Characterization of the developmental stages of sucking in preterm infants during bottle feeding. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:846–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pridham K, Brown R, Sondel S, Green C, Wedel NY, Lai HC. Transition time to full nipple feeding for premature infants with a history of lung disease. JOGN Nurs. 1998;27(5):533–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinneer MD, Beachy P. Nipple feeding premature infants in the neonatal intensive-care unit: factors and decisions. JOGN Nurs. 1994;23:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1994.tb01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]