Abstract

Tumors present numerous biobarriers to the successful delivery of nanoparticles. Decreased blood flows and high interstitial pressures in tumors dictate the degree of resistance to extravasation of nanoparticles. To understand how a nanoparticle can overcome these biobarriers, we developed a multimodal in vivo imaging methodology, which enabled the non-invasive measurement of microvascular parameters and deposition of nanoparticles at the microscopic scale. To monitor the spatiotemporal progression of tumor vasculature and its vascular permeability to nanoparticles at the microcapillary level, we developed a quantitative in vivo imaging method using an iodinated liposomal contrast agent and a micro-CT. Following perfusion CT for quantitative assessment of blood flow, small animal fluorescence molecular tomography was used to image the in vivo fate of cocktails containing liposomes of different sizes labeled with different NIR fluorophores. The animal studies showed that the deposition of liposomes depended on local blood flow. Considering tumor regions of different blood flow, the deposition of liposomes followed a size-dependent pattern. In general, the larger liposomes effectively extravasated in fast flow regions, while smaller liposomes performed better in slow flow regions. We also evaluated whether the tumor retention of nanoparticles is dictated by targeting them to a receptor overexpressed by the cancer cells. Targeting of 100-nm liposomes showed no benefits at any flow rate. However, active targeting of 30-nm liposomes substantially increased their deposition in slow flow tumor regions (~12-fold increase), which suggested that targeting prevented the washout of the smaller nanoparticles from the tumor interstitium back to blood circulation.

Keywords: Nanoparticle contrast agent, high resolution imaging, nanoparticle extravasation, transport of nanoparticles, angiogenesis, angiogram, blood flow, vascular permeability

Although nanoparticles should localize themselves with high specificity in solid tumors while reducing off-target delivery due to the so-called Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR) effect,1, 2 clinical data indicate that nanoparticle-based chemotherapy is not consistently effective.3–5 This has been attributed to the fact that nanoparticles have to overcome various tumor-related biobarriers (e.g. premature and tortuous blood vessels, high interstitial pressure, erratic blood flow), which highly vary between tumors of even the same stage.6–9 For example, the studies that led to the clinically adapted liposomal doxorubicin identified the 100-nm size as an optimal ‘compromise’.10–14 However, the uniqueness of each tumor was not taken under consideration. We have previously shown that a principal reason for differential tumor responsiveness to 100-nm liposomal doxorubicin is the differential microvascular permeability.15–17 These findings suggest that a single design of nanoparticles may not achieve equally high extravasation in all the regions of a tumor.

The deposition of nanoparticles into tumors is a complex process, which is governed by characteristics of the tumor microenvironment such as blood flow, physical gaps of the endothelial fenestrations, interstitial fluid pressure (IFP), and microvessel density. The overall transport of a nanoparticle is due to movement from applied convective forces and to a lesser degree Brownian motion.18 Thus, the extravasation of nanoparticles is partially governed by the rate of fluid flow and filtration along a capillary, which depends upon the hydrostatic pressure gradient (i.e. the difference between the vascular pressure and IFP).19 Decreased blood flows and high IFP are indicative of tumor’s degree of resistance to extravasation of nanoparticles.20 Thus, it is essential to understand the forces, which drive a nanoparticle to overcome the numerous biobarriers within a tumor. Our previous in vitro studies in microfluidic channels demonstrated that the margination of flowing nanoparticles (i.e. lateral drift towards the vessel walls) depends on their size and the flow rate.21 This indicates that the intravascular and transvascular transport of nanoparticles in a tumor’s region is governed by the relationship of particle size to the hemodynamics of that tumor’s region. Due to the convective transport of nanoparticles, as the particle size increases, faster blood flow patterns are required to overcome high IFP in tumors. Thus, we suggest that one nanoparticle formulation does not fit all the regions of a tumor, which motivated us to study tumor development and nanoparticle transport in real-time on a microscopic basis.

Here, we developed in vivo imaging tools to non-invasively evaluate the regional expression of functional, molecular and morphological biomarkers that affect the deposition of a nanoparticle inside a tumor. To simultaneously monitor the spatiotemporal progression of tumor vasculature and its vascular permeability, we developed a quantitative in vivo imaging method using a 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent and high-resolution micro-CT. We term this method nano-Contrast-Enhanced micro-CT (abbreviated as nCE-μCT). The nCE-μCT method provides a unique opportunity to non-invasively monitor the tumor vasculature development and accurately measure vascular permeability to the 100-nm liposomal agent at very high resolution (28 μm).15, 22, 23 Our initial step was to explore how vascular permeability is related to regional tumor blood flow and the expression of an angiogenic marker (i.e. αvβ3 integrin) using multimodal imaging. In addition to nCE-μCT, tumor blood flow and molecular imaging was performed using standard contrast-enhanced computed tomography (i.e. perfusion CT) and small animal fluorescence molecular imaging (i.e. FMT), respectively. While nCE-μCT can monitor the intratumoral deposition of a liposome at microscopic resolutions, one practical limitation stems from the fact that only a single liposome formulation can be tracked in the same tumor. To be able to simultaneously image the intratumoral deposition of different formulations, we then used FMT imaging. Following perfusion CT for quantitative assessment of tumor’s regional blood flow, FMT was used to image the in vivo fate of cocktails containing liposomes of different sizes (30, 65, and 100 nm in diameter) labeled with different NIR fluorophores. Co-registration of the imaging sets from the different modalities enabled the extraction of correlations between the regional deposition of differently sized liposomes and the blood flow in different regions of the same tumor. We also evaluated whether the tumor retention of liposomes is dictated by targeting them to a receptor overexpressed by the cancer cells. Thus, besides the EPR effect, we evaluated the relationship of tumor blood flow to active targeting and liposome size. Since tumor microenvironment is variable not only among different cancer types but also among tumors of the same cancer type and stage, we used two highly aggressive mammary adenocarcinoma animal models: the rat 13762 MAT B III model and the mouse 4T1 model.

The multimodal, noninvasive and longitudinal nature of this imaging approach enabled us to quantitatively assess the extravasation of nanoparticles in tumors in terms of their relation to regional blood flow, nanoparticle size and active targeting to overexpressed receptors. While the convective transport of nanoparticles is well acknowledged,18, 24 we found that the nanoparticle deposition in different tumor regions varied dramatically (anywhere from one to three orders of magnitude) depending on the particle size, receptor-targeting and blood flow.

Results

Longitudinal imaging of early tumor angiogenesis and vascular permeability

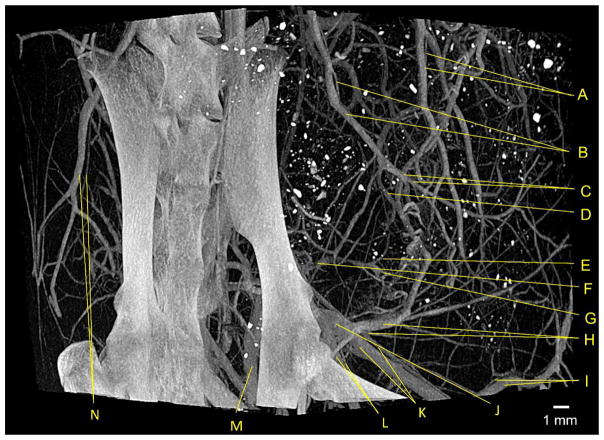

Following an injection of a 100-nm liposome encapsulating a high cargo of an iodinated contrast agent, we performed high resolution imaging of a rat using a micro-CT system. Imaging immediately after injection of the agent (early-phase post-injection) provided an accurate angiogram, since the majority of the detected signal should only be attributed to intravascular contrast agent. Due to the high intravascular signal (~1500 HU in the aorta) and spatial resolution (28 μm), Figure 1 provided a micromorphological angiogram, which gave detailed information of the microvasculature. We have performed early-phase post-injection nCE-μCT imaging to a large group of animals (n>15) resulting in consistently high-resolution images with high signal-to-noise ratio. Based on a study by Jain et al.,26 mammary adenocarcinomas in rodents present a capillary network composed of vessels with a mean length of 67 μm, a mean diameter of 10 μm, and a mean intercapillary distance of 49 μm. Thus, nCE-μCT imaging provided comparable resolution to the features of tumor microvasculature allowing us to non-invasively obtain tumor parameters that were relevant to our study.

Figure 1.

An example of a high-resolution angiogram using nCE-μCT. A rat bearing a 13762 MAT B III breast tumor inoculated into the mammary fat pad was injected with a high dose of iodinated nanoparticle contrast agent resulting in a blood pool concentration of 35 mg/mL iodine. Imaging was done 4 days after tumor inoculation using with nCE-μCT (high-resolution scan, 28 μm isotropic voxel). Major vascular structures were identified, including the: (A) Uterine vein and artery, (B) iliolumbar vein and artery, (C) lumbar branches of iliolumbar vein and artery, (D) iliac branch of iliolumbar vein, (E) left colic vein, (F) inferior mesenteric vein, (G) superior hemorrhoidal vein, (H) hypogastric vein and artery, (I) inferior epigastric vein and artery, (J) common iliac vein, (K) external iliac vein and artery, (L) internal iliac vein and artery, (M) l. internal iliac vein, (N) iliolumbar vein and artery.25 In all cases, the vein is the larger of the two labeled vessels.

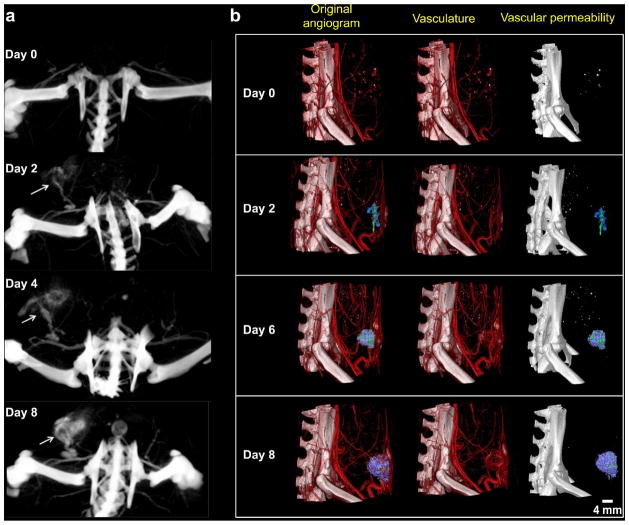

To observe angiogenesis at its earliest stages of development, a rat was injected with the 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent and longitudinally imaged by micro-CT for 8 days after tumor inoculation. A set of scans with a large field of view (85 × 85 × 98 mm) and resolution of 99 μm allowed us to compare blood vessel formation and structure in a mammary fat pad inoculated with a tumor and a healthy mammary fat pad (Figure 2a). Following systemic administration of the iodinated liposomal contrast agent, late-phase post-injection imaging enabled us to quantitatively track the development of tumor vasculature in a time-dependent manner. From the second day after inoculation, changes in feeding vessel size and vascular permeability, as evidenced by higher signal from increased nanoparticle extravasation, could be observed. In order to observe the developmental changes of the tumor vasculature in higher detail, we performed 28 μm-resolution scans. Figure 2b shows that tumor vasculature began to rapidly grow 2 days after tumor inoculation. Newly formed vessels in the tumor were observed to be highly irregular and tortuous in comparison to vessels in the healthy mammary fat pad. In addition, we have established a method for quantification of the extravasation of the iodinated liposomes without the interference of signal from the circulating liposomes in the blood.15, 16, 27 By applying thresholded colormaps to volume rendered images, manual segmentation was used to isolate regions with low extravasation (purple) from high extravasation (green). Importantly, the intratumoral deposition of the 100-nm liposome displayed significant differences from one region to the next. While Figure 2 shows an example from a single animal, this spatiotemporal variability in the development of tumor vasculature and its vascular permeability has been observed in the entire group of animals (n=4).

Figure 2.

An example of longitudinal imaging of the progression of tumor microvasculature and its permeability to a 100-nm liposome using nCE-μCT. (a) Large field of view and low resolution (99 μm) images of the initial steps of tumor development using longitudinal nCE-μCT imaging. A rat with a 13762 MAT B III tumor inoculated orthotopically in the mammary fat pad was imaged at 99 μm resolution before and on days 2, 4 and 8 after tumor inoculation. Maximum intensity projections (MIPs) show the lower abdominal region of the rat at the site of tumor inoculation. The white arrows label the area with tumor vasculature development and subsequent nanoparticle contrast agent extravasation. (b) Small field of view and high resolution (28 μm) images of the initial steps of tumor development using longitudinal nCE-μCT imaging. A rat with a 13762 MAT B III tumor inoculated orthotopically in the mammary fat pad was imaged before and on days 2, 6, and 8 after tumor inoculation. Column 1: A thresholded colormap was applied to volume rendered images in AMIRA, where manual segmentation was used to isolate regions with low extravasation (purple) from high extravasation (green). Column 2: Volume rendered images without manual segmentation. Column 3: Manually segmented extravasation in the absence of blood vessels.

Due to the longitudinal nature of the study and exposure to x-ray radiation for multiple days, we evaluated whether imaging with the micro-CT system significantly affected tumor viability in terms of apoptosis of cancer cells. The high-resolution micro-CT scan exposed the rats to ~4 Gy x-ray radiation. Post-mortem TUNEL staining was performed on multiple histological sections per animal to compare the level of apoptosis in irradiated and non-irradiated tumors (n=3 animals per condition). There was no significant difference in the apoptotic index (ratio of apoptotic to non-apoptotic cancer cells) between the two conditions, with the value being less than 1%. Using detailed histological analysis, we previously showed that the apoptotic index of mammary tumors in rodents was about 1% in the same timeframe as the one used here, which is consistent to our findings in this study.2

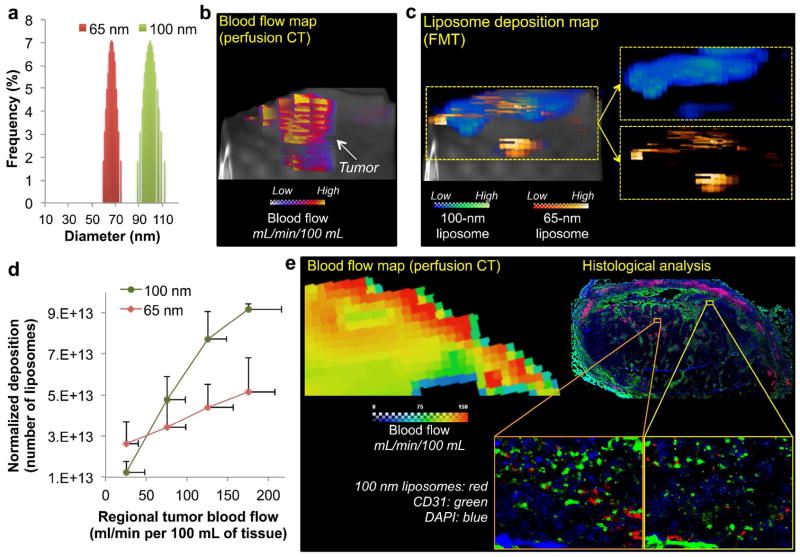

The effect of blood flow on the intratumoral deposition of liposomes in the rat MAT B III model

While nCE-μCT allowed us to quantitatively monitor the intratumoral deposition of the 100-nm liposome at microscopic resolutions, only a single liposome formulation was tracked. To simultaneously measure the intratumoral deposition of different formulations in the same tumor, we employed FMT imaging in a group of rats bearing MAT B III tumors (n=5). Initially, a tumor blood flow map was generated through quantitative assessment of tumor’s regional blood flow using standard clinical perfusion CT at an in-plane resolution of 152 × 152 μm2. Following perfusion CT, FMT was used to image the in vivo fate of a cocktail containing two liposomes with different sizes (65 and 100 nm in diameter; Figure 3a) labeled with different NIR fluorophores. Figures 3b and c show representative images of the blood flow map and the FMT-based liposome deposition map in the same tumor indicating the wide regional variability of blood flow and liposome deposition within the same tumor. Co-registration of the three-dimensional maps from the two different modalities allowed us to quantify the blood flow and deposition of the two liposome classes on a regional basis within the same tumor. While blood flow exhibited high variability in this tumor model, the blood flow range was not very wide compared to other types of tumors. Even with this relatively narrow blood flow range, Figure 3d illustrates that higher deposition for both liposome classes was favored in the regions with fast blood flows (e.g. 175 mL/min/100mL). Furthermore, the 100-nm liposome outperformed its 65-nm counterpart in the regions with fast flow. The opposite occurred in the regions with slow flow, which favored the 65-nm liposome more than the 100-nm one. To confirm the in vivo findings, we performed post-mortem histological evaluation. Care was taken to obtain tissue sections from the same location of the tumor with the same orientation as that of the blood flow map obtained using perfusion CT. A representative histological image is shown in Figure 3e, which indicates that greater number of 100-nm liposomes was found in tumor locations that exhibited high blood flow than regions with slow flow. These patterns were observed in multiple histological sections. As with most nanoparticles with sizes in the 100 nm range, the liposomes exhibited near-perivascular accumulation in the tumor interstitium. Complex cellular arrangements and components of the extracellular matrix in tumors create additional geometric restrictions that contribute to the diffusion limitations of nanoparticles.28 Even after successful extravasation and deposition in the near-perivascular region, nanoparticles remain proximal to the vessel wall. Dreher et al. showed that dextran with molecular weight of 2 MDa could only penetrate 5 μm from the vessel wall in 30 min.29 Liposomes with sizes ranging from 50–150 nm were shown to accumulate predominantly within 40–50 μm from the rim of avascular multicellular spheroids of about 400 μm in diameter consisting of prostate cancer cells.30

FIGURE 3.

Dependence of liposome deposition into tumors on the liposome size and blood flow. (a) The size distribution of two different liposome classes (65 and 100 nm) as measured by dynamic light scattering. (b) Perfusion CT was performed on rats with 13672 MAT B III tumors to generate 3D maps of blood flow in tumors. (c) Following tumor blood flow mapping, the tumor deposition of two different liposome classes (65 and 100 nm) was non-invasively measured using FMT imaging at 24 h after injection. To image the two liposome classes in the same tumors, distinct NIR fluorophores were used to distinguish each class of liposome inside the tumor. A representative 3D FMT image is shown as an example. (d) The intratumoral deposition of liposomes with two different sizes is shown as a function of regional blood flow in tumors. The injection dose of each liposome class contained equal number of particles. The deposition was normalized to the fractional blood volume (fBV) of each region. The data of blood flow and liposome deposition is presented as mean ± SD in a given 3D ROI (n=4 animals). (e). Fluorescence image of a histological section of a 13762 MAT B III tumor shows the microdistribution of 100-nm liposomes (5x magnification; red: 100-nm liposome; blue: nuclear stain (DAPI); green: endothelium (CD31)). Images of entire histological sections of the organs were obtained using the automated tiling function of the microscope. Care was taken to obtain tissue sections from the same location of the tumor with the same orientation as that of the blood flow map obtained using perfusion CT. Insets: The location of liposomes is shown with respect to blood vessels (10x magnification).

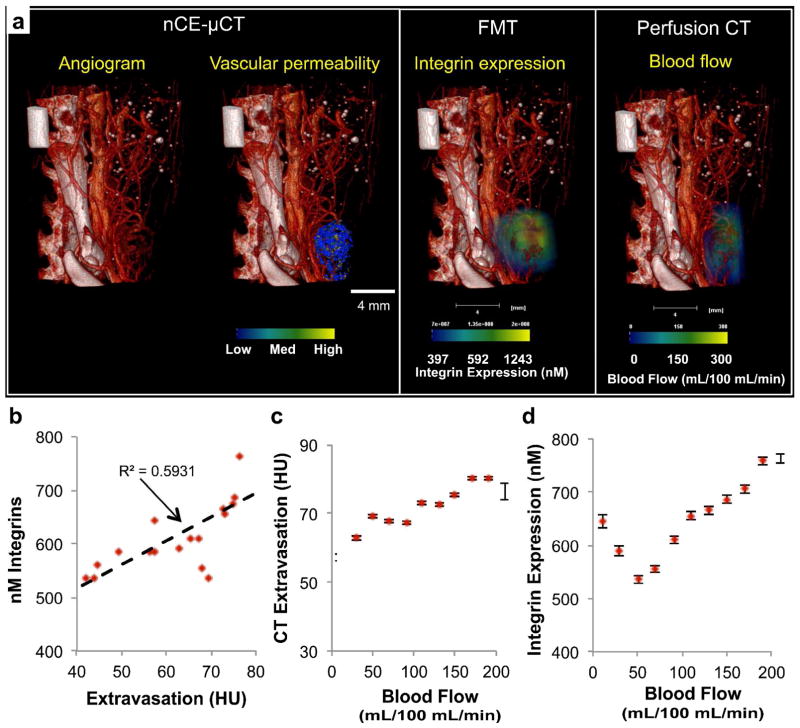

Multimodal imaging of functional tumor biomarkers in the mouse 4T1 model

Since tumor microvascular network varies widely among different types of tumors, we also tested the deposition of liposomes in an additional aggressive mammary adenocarcinoma model: the mouse 4T1 model. Initially, we employed the high-resolution nCE-μCT method to image the tumor microvasculature and the intratumoral deposition of the 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent. In addition to performing nCE-μCT imaging, we also measured regional blood flow and integrin expression in the same tumor (Figure 4a). FMT imaging enabled the quantification of the fluorescence signal from an integrin-targeting agent in 3D volumes. Using the three imaging modalities (micro-CT, perfusion CT and FMT), imaging was performed 24 hours after administration of an αvβ3 integrin-targeting NIR fluorescent agent and the 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent in order to allow time for the two agents to interact with the tumor endothelium. Previous work has fully characterized the αvβ3 integrin-targeting NIR fluorescent agent showing its high specificity for targeting αvβ3 integrin receptors.31 In addition, to illustrate the variable pattern of vascular permeability, we generated a map with bins of low, medium, and high extravasation of the liposomal contrast agent. Finally, a tumor blood flow map was generated through the standard clinical perfusion CT at an in-plane resolution of 152 × 152 μm2. Co-registration of the three-dimensional maps from the three different modalities and quantification of the integrin expression, vascular permeability and blood flow allowed us to explore potential correlations among morphological, functional and molecular biomarkers. For example, these measurements revealed that increased extravasation of the liposomal contrast agent correlated to increasing levels of integrin expression (Figure 4b) and high blood flows (Figure 4c). On the other hand, a nonlinear correlation was found between tumor blood flow and integrin expression (Figure 4d). Thus, high-resolution images of blood flow and liposome distribution in tumors can be analyzed to extract correlative extravasation patterns of differently sized liposomes in different regions of the same tumor.

Figure 4.

Multimodal in vivo imaging of vasculature, vascular permeability, integrin expression and blood flow in an orthotopic 4T1 mammary tumor in mouse. (a) Following nCE-μCT, FMT (after injection of integrin-targeting probe), and standard perfusion CT of the same animal with a mammary tumor, the angiogram (28 μm resolution) was overlaid with the map of vascular permeability, a map of integrin expression (FMT imaging), and a map of tumor blood flow (perfusion CT). Correlations were assessed between (b) vascular permeability and integrin expression, (c) vascular permeability and blood flow, and (d) blood flow and integrin expression. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean value of the measurement within each ROI (n=1 animal).

The effect of blood flow on the intratumoral deposition of different classes of liposomes in the mouse 4T1 model

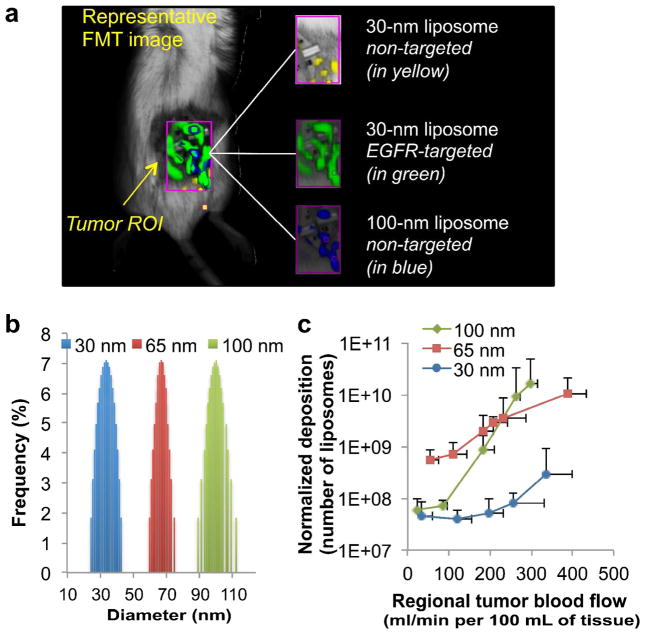

Equipped with a set of imaging tools capable of simultaneously assessing nanoparticle deposition and blood flow in unique regions of a tumor, we then explored how nanoparticles of different sizes behave in 4T1 tumors as a function of blood flow. In this study, we further explored this relation by testing three sizes of liposomes. Similarly to the rat tumor model, we used FMT imaging to non-invasively track the intratumoral deposition of a cocktail of three liposome classes with different sizes (labeled with different NIR fluorophores) into the same tumor (orthotopic mouse mammary 4T1 tumor). The distinct NIR fluorophores were used to distinguish each class of liposome inside the tumor (an example is shown in Figure 5a). As shown in Figure 5b, the three liposome classes exhibited distinct, narrow size distributions (termed as 30-nm, 65-nm and 100-nm liposome). Following perfusion CT imaging of the same animals (n=5 animals), the blood flow rates were analyzed and 3D regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn with their volume ranging from 10–60 mm3. We should note that each tumor presented 5–6 different blood flow zones. The fractional blood volume (fBV) varied from 1–25% of the ROI’s volume. Since fBV dictates the availability pool of liposomes for extravasation in any given ROI, the nanoparticle deposition was normalized to the fractional blood volume (fBV) of each region. As shown in Figure 5c, all the classes of liposomes displayed higher extravasation in the regions of faster flow than slow flow. Most importantly, considering tumor regions in terms of blood flow rate, the deposition of liposomes exhibited variable patterns in different tumor regions. The patterns were observed to be different for liposomes of different sizes. In general, the larger liposomes effectively extravasated in fast flow regions, while the opposite occurred in the slow flow regions (with the exception of the 30-nm liposome). The faster flow significantly benefited the extravasation of the 100 nm liposome. In fact, their deposition was ~2 orders of magnitude higher in fast flow regions compared to slow flow regions. The blood flow had a weaker effect on the extravasation of the 65 nm liposomes. However, in the slow flow regions, the 65-nm liposome significantly outperformed the larger liposomes. The smallest liposomes (i.e. 30 nm) did not follow the size-dependent pattern, which suggests that the retention of smaller liposomes into the slow flow regions was much lower than that of larger liposomes.

Figure 5.

Dependence of liposome extravasation into tumors on the liposome size and blood flow on a region-by-region basis. (a) The intratumoral deposition of the different liposome classes (i.e. different sizes, targeted or non-targeted) was measured in an orthotopic mouse mammary tumor (4T1) using fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT). To image all four liposome classes in the same tumors, distinct NIR fluorophores were used to distinguish each class of liposome inside the tumor. A representative FMT image is shown as an example. (b) The size distribution of three different liposome classes (30, 65 and 100 nm) as measured by dynamic light scattering. (c) The intratumoral deposition of liposomes with the 3 different sizes is shown as a function of regional blood flow in tumors. Following tumor blood flow mapping using perfusion CT, the tumor deposition of the three different liposome classes (30, 65 and 100 nm) was non-invasively measured using FMT imaging at 24 h after injection. The injection dose of each liposome class contained an equal number of particles. The deposition was normalized to the fractional blood volume (fBV) of each region. The data of blood flow and liposome deposition is presented as mean ± SD in a given 3D ROI (n=5 animals; 5–6 tumor regions (flow zones) per animal per liposome class). The scale of the y-axis is logarithmic.

Furthermore, the liposome size is a critical factor that determines blood circulation, which in turn relates to tumor deposition.14 Since the administered dose containing the cocktail of different liposomes was 150 mg of lipids per kg of body weight, the reticuloendothelial system was not saturated and therefore the clearance rate of each liposome class may have varied.32, 33 However, there is no significant difference in the blood residence time of liposomes in the size range and timeframe used in our study.34

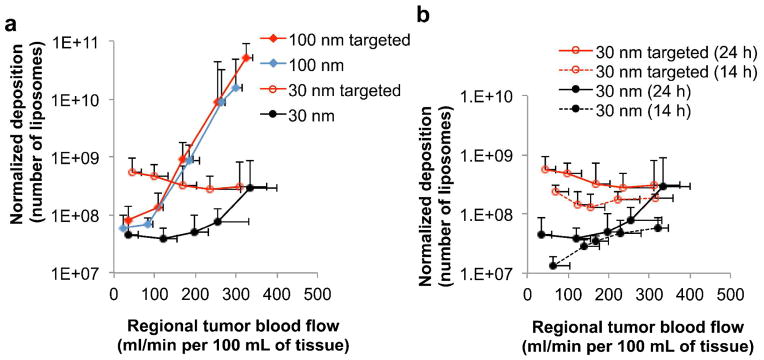

Since we expected the 30-nm liposomes to follow the same trend and achieve the highest deposition in the slow flow regions, we further investigated whether the issue with the 30-nm liposomes is related to their retention in the tumor. A targeted variant of each liposome class was synthesized by incorporating an EGFR-targeting peptide onto the distal end of the PEGs on the liposomal surface. We compared the 30-nm and 100-nm EGFR-targeting liposomes to their non-targeted variants (Figure 6a). While targeting of the 100-nm liposomes did not improve their deposition in slow or high flow regions, active targeting substantially increased the deposition of the 30-nm liposome in slow flow tumor regions (~12-fold increase). Imaging at a later time point (t=48 hrs) showed that EGFR-targeting further enhanced the retention of the 30-nm liposomes (~40-fold increase) in slow flow regions compared to their non-targeted variants (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Dependence of liposome extravasation into tumors on the liposome size, active targeting towards the EGF receptor, and blood flow on a region-by-region basis. (a) Following tumor blood flow mapping using perfusion CT, the intratumoral deposition of four different liposome classes (30 and 100 nm with or without EGFR-targeting ligands) was quantitatively measured in the orthotopic mouse (4T1) mammary tumor using FMT imaging at 24 h after injection. To image all four liposome classes in the same tumors, distinct NIR fluorophores were used to distinguish each class of liposome inside the tumor. The intratumoral deposition of liposomes is shown as a function of regional blood flow in tumors. (b) Comparison of the four liposome classes is shown at two different time points (i.e. 14 and 24 h after injection). The deposition was normalized to the fractional blood volume (fBV) of each region. The data of blood flow and liposome deposition is presented as mean ± SD in a given 3D ROI (n=5 animals; 5–6 tumor regions (flow zones) per animal per liposome class). The scale of the y-axis is logarithmic.

DISCUSSION

The 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent was used to assess spatiotemporal changes in tumor microvascular development and vascular permeability to nanoparticles at a resolution comparable to the microvascular features of tumors.20, 35 Using nCE-μCT imaging, high intravascular signal from the contrast agent enabled the observation of tumor vessel development at the capillary level. Angiography immediately after injection of the 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent (early-phase post-injection) enabled accurate observation of microvascular characteristics, since the 100-nm liposome behaves explicitly as an intravascular contrast agent. Late-phase micro-CT imaging at multiple time points allowed us to monitor the time-dependent regional deposition of the 100-nm liposomal contrast agent into the tumor. In conjunction to the high iodine cargo of the liposomes, the linear relationship between CT signal enhancement and iodine concentration facilitated time-dependent quantification of liposome deposition into tumors.15, 16, 27 It was found that tumor regions exhibited variable patterns of nanoparticle extravasation over time (Figure 2b). These temporal differences in vascular permeability imply that the efficacy of a single nanoparticle formulation may differ with time.

Previous clinical36 and preclinical37 studies demonstrated that transient increase of blood pressure (and subsequently tumor blood flow) resulted in enhanced delivery of nanoscale drugs to tumors that otherwise have modest EPR. Thus, we then explored if blood flow could gauge the likelihood that a nanoparticle would accumulate in a particular type of tumor. While perfusion CT cannot resolve the dynamics of an individual microvessel, it has sufficiently high resolution (in-plane: 152 × 152 μm2) and penetration depth to conduct regional flow analysis.38, 39 We performed these studies in two mammary adenocarcinoma models: the rat 13763 MAT B III and the mouse 4T1. Even in these ‘controlled’ tumor models of the same cell type, stage, and tumor size, regions with very different blood flows were identified which varied widely in topology from one tumor to the next, which is consistent with previous studies.40, 41 While nCE-μCT provided high resolutions, it only allowed to study the intratumoral deposition of a single liposome formulation. Therefore, we utilized small animal fluorescence imaging (FMT) to quantitatively and simultaneously image four different liposome formulations (labeled with a different NIR fluorophore) in the same tumor. Finally, we employed image processing to co-register the volume-rendered blood flow and liposome deposition maps. This enabled simultaneous volumetric measurement of regional blood flow, microvascular characteristics and liposome deposition, which allowed us to extract correlative patterns of the extravasation rates for each liposome class at different flow zones.

Our central hypothesis was that fast blood flow can help liposomes to overcome high IFP in tumors. We also anticipated that especially the larger liposome classes would not be able to overcome the high tumor interstitial fluid pressures under very slow blood flow resulting in minor extravasation (even when endothelium may be very leaky).18, 24, 42 In both animal models, blood flow in a tumor region affected the degree at which liposomes deposited in that specific region. These differences were more profound in the 4T1 model, because these tumors exhibited a wider range of blood flows (20–400 mL/min/100 mL). In the case of the largest liposome class (100 nm), Figure 5c shows that a significantly higher deposition (i.e. 340-fold) was observed in tumor regions with high flow than slow flow. While liposomes of any size extravasated in regions of both fast and slow flow, faster flow had a more dominant effect on aiding larger liposomes to overcome high interstitial pressures inside a tumor. We should emphasize that convective forces predominantly govern the transport of nanoparticles. While the contribution of diffusive transport is small, its relative contribution increases as the liposome size decreases. Therefore, the deposition of smaller liposomes depends less on blood flow than larger liposomes. Indeed, the 65 nm liposome class exhibited a similar trend to the 100 nm liposome with their deposition in high flow regions being 180-fold higher than slow flow regions. However, due to the relatively higher diffusion of the 65-nm liposome compared to the 100-nm variant, the 65-nm liposome required less convective forces than the 100-nm liposome to achieve similar deposition. These findings are in agreement with the mathematical analysis by Decuzzi et al., which showed that for a blood vessel of a fixed radius, nanoparticle deposition increases at higher flows.18

Interestingly, our in vivo studies showed that the smallest liposomes (i.e. 30 nm) did not follow the size-dependent pattern. Out of the three liposome classes, we were expecting the 30-nm liposome to exhibit the highest deposition in the slow flow regions. Due to the relatively high diffusivity of the smallest liposomes, we hypothesized that extravasated 30-nm liposomes re-enter the tumor microcirculation at much higher rates than larger liposomes do. Indeed, active targeting of the 30 nm liposome substantially increased its deposition in slow flow tumor regions (~12-fold increase), which may be attributed to increased retention due to active targeting that prevented the washout of the smaller nanoparticles from the tumor interstitium back to blood circulation. On the other hand, the deposition of 30-nm liposomes with or without targeting ligands in tumor regions of fast blood flow was statistically insignificant. This can be attributed to the fact that the higher intravascular pressure in regions of fast blood flow prohibits washout of 30-nm (targeted or non-targeted) liposomes back to bloodstream at much higher degree than the regions of slow blood flow. Targeting the 100 nm liposome showed no benefits at any flow rate. Because the relative contribution of diffusion is even smaller for the 100 nm liposome than the 30-nm variant, we believe that the deposited 100-nm liposomes remained in the tumor interstitium with or without a targeting moiety. Several prior studies have shown that while active targeting typically enhances the intracellular transport of the nanoparticles, there is no gain in the retention of nanoparticles with sizes of about 100 nm.43–49

Given that a tumor is heterogeneous in both its hemodynamics and its pathology, our study indicates that a single “one-size-fits-all” treatment might not be the most effective approach. We chose as a case study, the liposome, due to its clinical adaptation as a chemotherapeutic agent. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, an enormous number of studies concluded that a PEGylated unilamellar liposome composed of rigid phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol with a diameter between 50–150 nm displayed increased accumulation in tumors and antitumor activity.14, 50 The 100-nm liposome was chosen as the optimal compromise between loading efficiency of liposomes (increases with increasing size) and ability to extravasate (decreases with increasing size).51, 52 However, a close examination of the published literature indicates a variable in vivo performance among liposomes of different sizes, exhibiting significant overlap between the in vivo performance of liposomes of different sizes.14, 53–55 The results of our study suggest that there is a liposome size that maximizes deposition into a specific tumor region. One could envision that an a priori evaluation of regional blood flow in tumors can facilitate an ‘exclusive’ design of a cocktail of differently sized liposomes tailored to the hemodynamics of the different regions of a tumor. While liposomes of any size extravasate in all the regions, larger liposomes are a better ‘match’ for fast flow regions (and vice versa in the case of smaller liposomes). Most importantly, the outcomes from such tumor region-specific therapy could be generalizable to other types of nanoparticles, since other types of nanoparticles (e.g. polymeric, iron oxide, gold) can be fabricated in different sizes.56, 57

CONCLUSION

Considering the complexity of the microenvironment of tumors, multimodal in vivo imaging shed some light on the deposition of circulating nanoparticles in tumors. In conclusion, we show that an optimal nanoparticle size can be predicted in terms of maximum deposition in a specific tumor region, if the blood flow rate of that region is known. Furthermore, a critical liposome size exists below which active targeting substantially improves the intratumoral retention of nanoparticles, especially at slow blood flow regions. Thus, the use of an easily measured phenotypic biomarker (tumor blood flow)41, 58, 59 could facilitate the selection of a specific set of different nanoparticles to maximize the overall deposition into a specific tumor. This implies that therapeutic regimens could be individualized to the regional hemodynamic profile of a patient’s tumor to maximize the drug deposition in a tumor not just on a patient-by-patient but on a region-by-region basis.

METHODS

Animal model and care protocols

All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional, US, and international regulations and standards on animal welfare and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. Female Fischer F344 rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) and BALBc/4j mice (Jackson Laboratories, ME) were used. The 13762 MAT B III (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) rat tumor model was used for the longitudinal CT imaging study. For multimodal imaging and the assessment of liposome deposition of different sizes, the 4T1 mammary adenocarcinoma mouse tumor model was used. The tumors were orthotopically implanted by injecting 5 × 105 13762 MAT B III cells or 4T1 cells into the #9 mammary fat pad of the rat or mouse, respectively. After imaging, animals were anesthesized and transcardially perfused with heparinized PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The tumors were soaked in 30% sucrose (w/v) in PBS at 4° C and then cryosectioned. Slides were stained with both DAPI and a TUNEL stain (Promega) to qualitatively assess cell apoptosis.

Fabrication of iodinated liposomal contrast agent

The long circulating liposomal-iodinated contrast agent was fabricated using established methods 23. A highly concentrated iodine solution (525 mg I/mL) was prepared by dissolving iodixanol powder in deionized water at 60 C and mixed with lipids (56:4:40 Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine(DPPC): 1,2-Distearoyl-phosphatidyl ethanolamine-methyl-polyethyleneglycol (DSPE-mPEG):cholesterol) dissolved in ethanol. Liposomes were sequentially sized using an extruder (Lipex). After extrusion, the resulting solution was diafiltered using a MicroKros module (Spectrum Laboratories, CA) of 500 kDa molecular weight cutoff to remove unencapsulated iodixanol. Liposome size was characterized through dynamic light scattering (mean size ~100 nm) and iodine concentration (110 mg I/mL) was verified through UV spectrophotometry (λ=245 nm).

X-ray computed tomography scanning parameters and protocols

Computed tomography imaging was performed using the Inveon micro-CT system (Siemens Healthcare, AG). All scans were Hounsfield calibrated and had a tube voltage of 80 kVp, tube current of 500 μA, 180 projections, and a 512 × 512 × 512 reconstruction matrix. Two CT scanning protocols were developed: a 99 μm pixel resolution protocol with a 120 ms exposure time and an 85 × 85 × 98 mm field of view and a 28 μm pixel resolution protocol with a 400 ms exposure time and a 43 × 43 × 30 mm field of view. The rat was imaged on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 after tumor inoculation with both scanning protocols. In an independent subset of rats, the daily clearance of the contrast agent was monitored through CT measurement of blood pool contrast, in Hounsfield Units or HU (Figure S1 in Supporting Information), which exhibited a linear relationship. This was used to calculate the necessary follow-up doses of contrast agent to maintain a blood pool concentration of 35 mg I/mL (2.24 g/kg), which corresponds to about 1,500 HU. Thus, a small injection volume of the liposomal contrast agent (200–350 μL) was typically administered every two days to compensate for a signal drop of 270 HU.

Multimodal imaging of tumor blood flow, vascular permeability, integrin expression and microvessel density

A BALB/cJ mouse was maintained on a low fluorescence diet two weeks prior to imaging. Blood flow measurements were obtained through dynamic contrast enhanced computed tomography (DCE-CT). A dynamic perfusion scan (80 scans, 0.5 s rotation time, 12 consecutive slices) was taken with a 24 slice CT scanner (Sensation Open, Siemens Medical Systems, 80 kV, 150 mAs, detector width = 1.2 mm, slice thickness = 2.4 mm). Five seconds after scan initiation, a 100 μL bolus of Visipaque contrast agent (GE Healthcare, 320 mg I/mL) was administered through tail vein injection. Siemens Body Perfusion CT syngo software, employing the Patlak perfusion model and a user defined arterial input function, was used to calculate regional blood flow at an in-plane resolution of 152 × 152 μm2. The mouse was then imaged in the FMT before tail vein administration of the 100-nm iodinated liposomal contrast agent (250 mg/kg iodine) and an integrin-targeting fluorescent agent (Perkin Elmer, MA). Imaging was conducted with FMT and μCT 24 hours after cocktail administration. Following these scans, the mouse was injected with a high dose of iodinated liposome contrast agent (3 g/kg) and euthanized. The mouse was re-imaged in the μCT to obtain a high resolution (28 μm), high contrast angiogram.

Correlation of tumor blood flow to intratumoral deposition of different liposomes

In an independent subset of mice with 4T1 or rats with MAT B III tumors, tumors were allowed to grow for 2 weeks. Blood flow maps of the tumors were acquired with perfusion CT using methods previously described. Following blood flow map acquisition, a cocktail containing liposomes of different and distinct sizes was injected intravenously once at t=0. Each class of liposomes was labeled with a different near-infrared fluorophore (Vivotag 750, 680, 635, respectively; Perkin Elmer, MA) for quantitative imaging using FMT. The administered cocktail contained equal number of each liposome class. Animals were imaged using FMT at 14 or 24 hours after injection of the cocktail containing the different liposomes.

Image Analysis

All images were analyzed using the AMIRA software (Visage Imaging, CA). Manual segmentation and thresholding was used to isolate individual blood vessels. The multi-modal images were manually registered to the best of our ability using regional landmarks applied to the skin of the animal. Regional liposome extravasation, integrin expression, and blood flow were quantified on the microCT, FMT, and DCE-CT images, respectively, using the AMIRA MaterialStatistics function. To assess liposome deposition at different blood flows, FMT images at 4 channels were registered to a three-dimensional volume of blood flow. Zones of blood flow were chosen a priori using a histogram of regional blood flows from a full tumor. 3D regions of interest encapsulating these zones were selected by masking of blood flow images in AMIRA. The volume of these regions of interest ranged from 10–60 mm3 in size. Deposition of each class of liposome was measured at different zones of blood flow. In addition, we also measured the fractional Blood Volume (fBV) in each ROI, which indicates the source of liposomes in the blood available for extravasation.

Histological evaluation

After the last imaging acquisition, tumors were collected for histological studies. The animals were anesthetized with an IP injection of ketamine/xylazine and transcardially perfused with heparinized PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Tumors were explanted and post-fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The tissues were soaked in 30% sucrose (w/v) in PBS at 4 °C for cryosectioning. Serial sections of 12 μm thickness were collected using a cryostat (Leica CM 300). To visualize the tumor microvasculature, the tissue slices were immunohistochemically stained for the endothelial antigen CD31 (BD Biosciences, Pharmingen). The tissues were also stained with the nuclear stain DAPI. The tissue sections were imaged at 5 and 10 on the Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 motorized FL inverted microscope. To obtain an image of the entire tissue section, a montage of each section was made using the automated tiling function of the microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Correlations between regional tumor blood flow, regional vascular permeability, and regional nanoparticle extravasation in the same animal were assessed independently using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Means were determined for each variable in this study and the resulting values from each experiment were subjected to one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni test. A P value of less than 0.01 was used to confirm significant differences. Normality of each data set was confirmed using the Anderson-Darling test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a pilot grant from the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center P30 CA043703 (EK). R.T. was supported by a fellowship from the NIH Interdisciplinary Biomedical Imaging Training Program (5T32EB007509). Z.B. was supported by a fellowship from the NIH Medical Student Research Training grant (T35HL082544). We thank Patiwet Wuttisarnwattana, Mohammad Qutaish, and David Prabhu for technical assistance with image analysis in AMIRA, Ruth Keri for providing us with the 4T1 cell line for use in the multimodal imaging and liposome deposition studies, Joseph Young for conducting CT scans to perform blood flow measurements, Joseph Molter for technical assistance with the micro-CT, and Sourabh Shukla, Kaitlyn Murray, Swetha Rao and Aaron Abramowski for assisting with animal experiments and histology.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Additional figures and experimental details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor Vascular Permeability and the EPR Effect in Macromolecular Therapeutics: A Review. J Controlled Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris PM, Bauer L, Toy R, Tran E, Pansky J, Doolittle E, Schmidt E, Hayden E, Mayer A, Keri RA, et al. Enhanced Delivery of Chemotherapy to Tumors Using a Multicomponent Nanochain with Radio-Frequency-Tunable Drug Release. ACS Nano. 2012;6:4157–4168. doi: 10.1021/nn300652p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Service RF. Materials and Biology. Nanotechnology Takes Aim at Cancer. Science. 2005;310:1132–1134. doi: 10.1126/science.310.5751.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari M. Cancer Nanotechnology: Opportunities and Challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:161–171. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pope-Harman A, Cheng MM, Robertson F, Sakamoto J, Ferrari M. Biomedical Nanotechnology for Cancer. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:899–927. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto J, Annapragada A, Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. Antibiological Barrier Nanovector Technology for Cancer Applications. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2007;4:359–369. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor Microenvironment Abnormalities: Causes, Consequences, and Strategies to Normalize. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:937–949. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobbs SK, Monsky WL, Yuan F, Roberts WG, Griffith L, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Regulation of Transport Pathways in Tumor Vessels: Role of Tumor Type and Microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4607–4612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan F, Chen Y, Dellian M, Safabakhsh N, Ferrara N, Jain RK. Time-Dependent Vascular Regression and Permeability Changes in Established Human Tumor Xenografts Induced by an Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor/Vascular Permeability Factor Antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14765–14770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan F, Leunig M, Huang SK, Berk DA, Papahadjopoulos D, Jain RK. Microvascular Permeability and Interstitial Penetration of Sterically Stabilized (Stealth) Liposomes in a Human Tumor Xenograft. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3352–3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lasic DD, Papahadjopoulos D. Liposomes Revisited. Science. 1995;267:1275–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.7871422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabizon A, Goren D, Horowitz AT, Tzemach D, Lossos A, Siegal T. Long-Circulating Liposomes for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy: A Review of Biodistribution Studies in Tumor-Bearing Animals. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 1997;24:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida O, Maruyama K, Sasaki K, Iwatsuru M. Size-Dependent Extravasation and Interstitial Localization of Polyethyleneglycol Liposomes in Solid Tumor-Bearing Mice. Int J Pharm. 1999;190:49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagayasu A, Uchiyama K, Kiwada H. The Size of Liposomes: A Factor Which Affects Their Targeting Efficiency to Tumors and Therapeutic Activity of Liposomal Antitumor Drugs. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 1999;40:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karathanasis E, Suryanarayanan S, Balusu SR, McNeeley K, Sechopoulos I, Karellas A, Annapragada AV, Bellamkonda RV. Imaging Nanoprobe for Prediction of Outcome of Nanoparticle Chemotherapy by Using Mammography. Radiology. 2009;250:398–406. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502080801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karathanasis E, Chan L, Balusu SR, D’Orsi CJ, Annapragada AV, Sechopoulos I, Bellamkonda RV. Multifunctional Nanocarriers for Mammographic Quantification of Tumor Dosing and Prognosis of Breast Cancer Therapy. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4815–4822. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karathanasis E, Park J, Agarwal A, Patel V, Zhao F, Annapragada AV, Hu X, Bellamkonda RV. Mri Mediated, Non-Invasive Tracking of Intratumoral Distribution of Nanocarriers in Rat Glioma. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:315101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/31/315101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decuzzi P, Causa F, Ferrari M, Netti PA. The Effective Dispersion of Nanovectors within the Tumor Microvasculature. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:633–641. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Netti PA, Roberge S, Boucher Y, Baxter LT, Jain RK. Effect of Transvascular Fluid Exchange on Pressure-Flow Relationship in Tumors: A Proposed Mechanism for Tumor Blood Flow Heterogeneity. Microvasc Res. 1996;52:27–46. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald DM, Baluk P. Significance of Blood Vessel Leakiness in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5381–5385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toy R, Hayden E, Shoup C, Baskaran H, Karathanasis E. The Effects of Particle Size, Density and Shape on Margination of Nanoparticles in Microcirculation. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:115101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/11/115101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badea CT, Athreya KK, Espinosa G, Clark D, Ghafoori AP, Li Y, Kirsch DG, Johnson GA, Annapragada A, Ghaghada KB. Computed Tomography Imaging of Primary Lung Cancer in Mice Using a Liposomal-Iodinated Contrast Agent. PLoS One. 7:e34496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghaghada KB, Badea CT, Karumbaiah L, Fettig N, Bellamkonda RV, Johnson GA, Annapragada A. Evaluation of Tumor Microenvironment in an Animal Model Using a Nanoparticle Contrast Agent in Computed Tomography Imaging. Acad Radiol. 18:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentile F, Ferrari M, Decuzzi P. The Transport of Nanoparticles in Blood Vessels: The Effect of Vessel Permeability and Blood Rheology. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:254–261. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9423-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Less JR, Skalak TC, Sevick EM, Jain RK. Microvascular Architecture in a Mammary Carcinoma: Branching Patterns and Vessel Dimensions. Cancer Res. 1991;51:265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene GC. Anatomy of the Rat. Hafner Publishing Company; New York: 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karathanasis E, Chan L, Karumbaiah L, McNeeley K, D’Orsi CJ, Annapragada AV, Sechopoulos I, Bellamkonda RV. Tumor Vascular Permeability to a Nanoprobe Correlates to Tumor-Specific Expression Levels of Angiogenic Markers. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluen A, Boucher Y, Ramanujan S, McKee TD, Gohongi T, di Tomaso E, Brown EB, Izumi Y, Campbell RB, Berk DA, et al. Role of Tumor-Host Interactions in Interstitial Diffusion of Macromolecules: Cranial Vs. Subcutaneous Tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4628–4633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081626898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dreher MR, Liu W, Michelich CR, Dewhirst MW, Yuan F, Chilkoti A. Tumor Vascular Permeability, Accumulation, and Penetration of Macromolecular Drug Carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:335–344. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kostarelos K, Emfietzoglou D, Papakostas A, Yang WH, Ballangrud A, Sgouros G. Binding and Interstitial Penetration of Liposomes within Avascular Tumor Spheroids. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:713–721. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kossodo S, Pickarski M, Lin SA, Gleason A, Gaspar R, Buono C, Ho G, Blusztajn A, Cuneo G, Zhang J, et al. Dual in Vivo Quantification of Integrin-Targeted and Protease-Activated Agents in Cancer Using Fluorescence Molecular Tomography (FMT) Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12:488–499. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu D, Mori A, Huang L. Role of Liposome Size and RES Blockade in Controlling Biodistribution and Tumor Uptake of GM1-Containing Liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1104:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90136-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oja CD, Semple SC, Chonn A, Cullis PR. Influence of Dose on Liposome Clearance: Critical Role of Blood Proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1281:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Litzinger DC, Buiting AM, van Rooijen N, Huang L. Effect of Liposome Size on the Circulation Time and Intraorgan Distribution of Amphipathic Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Containing Liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1190:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rygh CB, Qin S, Seo JW, Mahakian LM, Zhang H, Adamson R, Chen JQ, Borowsky AD, Cardiff RD, Reed RK, et al. Longitudinal Investigation of Permeability and Distribution of Macromolecules in Mouse Malignant Transformation Using Pet. Clin Cancer Res. 17:550–559. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagamitsu A, Greish K, Maeda H. Elevating Blood Pressure as a Strategy to Increase Tumor-Targeted Delivery of Macromolecular Drug Smancs: Cases of Advanced Solid Tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia Enables Tumor-Specific Nanoparticle Delivery: Effect of Particle Size. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4440–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cenic A, Nabavi DG, Craen RA, Gelb AW, Lee TY. Dynamic CT Measurement of Cerebral Blood Flow: A Validation Study. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:63–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cosgrove D, Lassau N. Imaging of Perfusion Using Ultrasound. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 37(Suppl 1):S65–85. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brix G, Bahner ML, Hoffmann U, Horvath A, Schreiber W. Regional Blood Flow, Capillary Permeability, and Compartmental Volumes: Measurement with Dynamic CT--Initial Experience. Radiology. 1999;210:269–276. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.1.r99ja46269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, Exner AA, Krupka TM, Weinberg BD, Patel R, Haaga JR. Radiofrequency Ablation: Post-Ablation Assessment Using CT Perfusion with Pharmacological Modulation in a Rat Subcutaneous Tumor Model. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. Design Maps for Nanoparticles Targeting the Diseased Microvasculature. Biomaterials. 2008;29:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabizon A, Horowitz AT, Goren D, Tzemach D, Shmeeda H, Zalipsky S. In Vivo Fate of Folate-Targeted Polyethylene-Glycol Liposomes in Tumor-Bearing Mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6551–6559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goren D, Horowitz AT, Zalipsky S, Woodle MC, Yarden Y, Gabizon A. Targeting of Stealth Liposomes to Erbb-2 (HER/2) Receptor: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1749–1756. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang X, Peng X, Wang Y, Shin DM, El-Sayed MA, Nie S. A Reexamination of Active and Passive Tumor Targeting by Using Rod-Shaped Gold Nanocrystals and Covalently Conjugated Peptide Ligands. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5887–5896. doi: 10.1021/nn102055s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabizon A, Horowitz AT, Goren D, Tzemach D, Shmeeda H, Zalipsky S. In Vivo Fate of Folate-Targeted Polyethylene-Glycol Liposomes in Tumor-Bearing Mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6551–6559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Horowitz AT, Zalipsky S. Tumor Cell Targeting of Liposome-Entrapped Drugs with Phospholipid-Anchored Folic Acid-PEG Conjugates. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56:1177–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JW, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Colbern G, Shalaby R, Baselga J, Shao Y, Nielsen UB, Marks JD, Moore D, et al. Anti-HER2 Immunoliposomes: Enhanced Efficacy Attributable to Targeted Delivery. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1172–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park JW, Kirpotin DB, Hong K, Shalaby R, Shao Y, Nielsen UB, Marks JD, Papahadjopoulos D, Benz CC. Tumor Targeting Using Anti-HER2 Immunoliposomes. J Controlled Release. 2001;74:95–113. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papahadjopoulos D, Allen TM, Gabizon A, Mayhew E, Matthay K, Huang SK, Lee KD, Woodle MC, Lasic DD, Redemann C, et al. Sterically Stabilized Liposomes: Improvements in Pharmacokinetics and Antitumor Therapeutic Efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11460–11464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lasic DD. Novel Applications of Liposomes. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:307–321. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lasic D, Martin F. Stealth Liposomes. CRC Press Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagayasu A, Shimooka T, Kinouchi Y, Uchiyama K, Takeichi Y, Kiwada H. Effects of Fluidity and Vesicle Size on Antitumor Activity and Myelosuppressive Activity of Liposomes Loaded with Daunorubicin. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994;17:935–939. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nagayasu A, Uchiyama K, Nishida T, Yamagiwa Y, Kawai Y, Kiwada H. Is Control of Distribution of Liposomes between Tumors and Bone Marrow Possible? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1278:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uchiyama K, Nagayasu A, Yamagiwa Y, Nishida T, Harashima H, Kiwada H. Effects of the Size and Fluidity of Liposomes on Their Accumulation in Tumors: A Presumption of Their Interaction with Tumors. Int J Pharm. 1995;121:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Jong WH, Hagens WI, Krystek P, Burger MC, Sips AJ, Geertsma RE. Particle Size-Dependent Organ Distribution of Gold Nanoparticles after Intravenous Administration. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1912–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Mizuno K, Chen Q, Murakami M, Kimura M, Terada Y, Kano MR, Miyazono K, Uesaka M, et al. Accumulation of Sub-100 nm Polymeric Micelles in Poorly Permeable Tumours Depends on Size. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:815–823. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Q, Yuan ZG, Wang DQ, Yan ZH, Tang J, Liu ZQ. Perfusion CT Findings in Liver of Patients with Tumor During Chemotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 16:3202–3205. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i25.3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cenic A, Nabavi DG, Craen RA, Gelb AW, Lee TY. A CT Method to Measure Hemodynamics in Brain Tumors: Validation and Application of Cerebral Blood Flow Maps. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:462–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.