Abstract

Predictable patterns in early parent-child interactions may help lay the foundation for how children learn to self-regulate. The present study examined contingencies between maternal teaching and directives and child compliance in mother-child problem-solving interactions at age 3.5 and whether they predicted children’s behavioral regulation and dysregulation (inhibitory control and externalizing behaviors) as rated by mothers, fathers, and teachers at a 4-month follow-up (N = 100). The predictive utility of mother- and child-initiated contingencies was also compared to that of frequencies of individual mother and child behaviors. Structural equation models revealed that a higher probability that maternal directives were followed by child compliance predicted better child behavioral regulation, whereas the reverse pattern and the overall frequency of maternal directives did not. For teaching, stronger mother- and child-initiated contingencies and the overall frequency of maternal teaching all showed evidence for predicting better behavioral regulation. Findings depended on which caregiver was rating child outcomes. We conclude that dyadic measures are useful for understanding how parent-child interactions impact children’s burgeoning regulatory abilities in early childhood.

Keywords: parent-child interaction, teaching, self-regulation, early childhood

Children’s regulatory skills contribute to their successful adaptation to school (Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007; Rimm-Kaufman & Kagan, 2005). The abilities to inhibit impulsive and dysregulated behavior and persist at a caregiver-directed task are essential skills in the early school years (Dennis, 2006; Kochanska, 1993) and may be key components of school readiness (Denham, Warren-Khot, Bassett, Wyatt, & Perna, 2012). However, there is more to learn about the effects of parent-child teaching interactions on behavioral regulation and dysregulation before children attend school. We would expect that the way parents teach their children and how children respond to this instruction sets the stage for children’s regulatory abilities in later learning situations. However, findings regarding the link between parental teaching and children’s regulatory abilities has been mixed (Eisenberg et al., 2010). Thus, the present study examined parent-preschooler teaching interactions and their effects on children’s behavioral regulation and dysregulation. Of particular interest was whether the use of dyadic measures (in addition to individual measures) helped to clarify this link by better reflecting the interdependent nature of parent-child interactions. For the purposes of the present study, behavioral regulation and dysregulation were operationalized as inhibitory control and externalizing behavior problems, respectively, which have been shown to be salient indices of behavioral adjustment in the preschool years (Fantuzzo & McWayne, 2002; Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001; Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005).

Parental Teaching and Children’s Behavioral Regulation

Although parents do not typically receive training in teaching methods, they must teach their children beginning early in life. We would expect that high levels of parental support would provide a context for children’s regulatory development as children learn how to persist in the face of difficulty (Vygotsky, 1978). Research generally suggests this, showing that behaviors such as scaffolding and responsiveness (Denham et al., 2000; Mulvaney, McCartney, Bub, & Marshall, 2006) and positive reinforcement and proactive parenting (Lunkenheimer et al., 2008) predict higher levels of self-regulation and behavioral adjustment in early childhood.

There is less research that addresses specific parental teaching behaviors (Eisenberg et al., 2010). In the present study, “teaching” was defined as instances when the parent explained how something worked (e.g., “ I think this piece goes in the middle”) or open-ended questions that allowed the child the opportunity to respond (e.g., “Where do you think it goes?”). One proposed theoretical mechanism is that teaching that involves support for autonomy contributes to the child’s repertoire of regulatory strategies, thus increasing persistence on caregiver-directed tasks. For instance, open-ended teaching questions could prompt the child to consider other task solutions (Sigel, Stinson, & Kim, 1993), which could activate regulatory strategies. When parents provide instruction, it may also help children avoid the inattention associated with task difficulty (Fagot & Gauvain, 1997; Hoffman, Crnic, & Baker, 2006). One study showed that when mothers supported autonomy by providing 2 and 3.5 year-olds a choice on a task, children showed greater task persistence at 4.5 years (Landry, Smith, Swank, & Miller-Loncar, 2000). Further, mothers’ direct instruction and open-ended teaching questions at age 3.5 predicted higher emotion regulation at ages 6–7 (Supplee, Shaw, Hailstones, & Hartman, 2004). However, other studies have not found this relationship (Bomba, Goble, & Moran, 1994; Gilmore, Cuskelly, Jobling, & Hayes, 2009). For example, Gartstein and Fagot (2003) found that higher levels of parental cognitive guidance at age 5 predicted children’s higher, not lower, levels of externalizing behaviors.

Parent-child interactions are interdependent, and thus it is also important to consider the evocative effects of child behavior on parental teaching. Parents are believed to adjust their teaching behaviors according to the needs of their child and the environmental context (Vygotsky, 1978). Mothers are likely to engage more when it is needed to keep the child on task (Robinson, Burns, & Davis, 2009), and child performance becomes progressively caregiver-regulated with increasing task difficulty (McNaughton & Leyland, 1999). A study by Eisenberg et al. (2010) showed evocative effects of children’s effortful control (a temperament-based form of self-regulation) at age 2.5 predicting later maternal teaching strategies, although the reverse (teaching predicting effortful control) was not found. There is also general support for the importance of evocative child effects, showing that characteristics of the child (e.g., temperament) elicit different responses from parents and caregivers, and the corresponding interaction that occurs contributes to the dynamic process of child development (Dennis, 2006; Lytton, 1990; Scaramella, Sohr-Preston, Mirabile, Robison, & Callahan, 2008).

Given the mixed findings regarding the relationship between maternal teaching and children’s regulatory skills, additional research on bidirectional processes is needed to answer the following question: when parents offer the child an opportunity to exercise problem-solving and children make use of these opportunities, or conversely, when children engage in problem-solving and parents predictably respond by offering them additional instruction, do these patterns help lay the foundation for children’s behavioral regulation? Given the dynamic nature of interactions with preschoolers, one possibility is that this relationship could be clarified through the use of dyadic, real-time measures of the parent-child teaching process.

Contingencies in Parent-Child Interaction

Theory and empirical evidence point to the importance of dyadic parent-child contingencies in children’s regulatory development (Cole, Teti, & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Olson & Lunkenheimer, 2009; Sameroff & Chandler, 1975). In theory, we would expect that the more predictable a particular behavioral coupling (e.g., maternal directives and child compliance), the more it would encourage the repetition and stabilization of the child skill in question (Patterson & Bank, 1989), particularly during a formative period for the development of behavioral regulation. In particular, behavioral contingencies between parental direction and child compliance appear to be important correlates and predictors of children’s regulatory capacities and adjustment (Scaramella et al., 2008). Research shows that competent children and their mothers show contingent patterns of maternal discipline and child compliance, whereas dysregulated children and their mothers show contingencies around coercive control and noncompliance (Dumas, LaFreniere, & Serketich, 1995). Child compliance is also a well-established precursor of self-regulation in the broader literature (Kochanska et al., 2001).

Contingencies around parental direction may operate differently from those around teaching, because direct commands do not typically offer the child a choice as to their behavior or the opportunity to practice autonomy. In the present study, we defined directives as syntactic commands (e.g., “Put that there” or “Don’t turn it”) that indicated a clear agenda and did not provide the child a choice of behavior, but reflected guidance as opposed to harsh discipline (Grolnick & Pomerantz, 2009). Directives may be appropriate forms of guidance for children who are young, do not yet have the skills to self-regulate (Heckhausen, 1999), or have difficulties with self-regulation (Wertsch, 1979). However, it has also been argued that if directives are used exclusively at the expense of other forms of parental guidance (e.g., teaching), children may not develop autonomy in learning situations and may become overwhelmed, act out, or look to others for externally-based forms of regulation when challenge occurs (Wertsch, 1979). Thus, the question remains as to whether contingent cycles of maternal teaching and child behavior in problem-solving situations relate to children’s behavioral regulation, and if so, how their effects compare to the contingencies between maternal directives and child compliance already established in the literature.

The Present Study

The present study investigated contingencies between maternal teaching and directives and child compliance as mothers instructed their preschoolers to complete a difficult problem-solving task in the laboratory. These maternal behaviors were selected because they differed in the degree to which they offered children the opportunity to self-regulate in a learning situation. We were interested in their effects on children’s inhibitory control and externalizing behaviors, as these are important indices of behavioral regulation and dysregulation in early childhood (Fantuzzo & McWayne, 2002; Olson et al., 2005). Our first research question was, do contingencies between maternal teaching and child compliance (both mother- and child-initiated sequences) predict children’s behavioral regulation and dysregulation as rated by mothers, fathers, and teachers? Although research has centered on contingencies between parental direction and child compliance to date (Dumas et al., 1995), we hypothesized that contingencies between teaching and compliance would also contribute to children’s better behavioral regulation because children might be more likely to internalize self-regulation as a result of opportunities that allowed them to practice regulatory skills.

Another goal was to examine whether the use of a particular methodology (dyadic, real-time measures of contingency patterns) helped to clarify prior mixed findings regarding the link between parental teaching and children’s behavioral regulation and dysregulation in early childhood. To examine this, we compared the predictive utility of transitional probabilities between mother and child behaviors to frequencies of individual mother and child behaviors. Thus, the second research question was, do dyadic contingencies in teaching interactions show better utility in predicting children’s behavioral regulation and dysregulation than frequencies of individual mother and child behaviors? We hypothesized that dyadic contingencies would show better predictive utility because they would better reflect the interdependent nature of the teaching process.

In testing these questions, we accounted for factors shown to be involved in the link between parent-child interactions and children’s behavioral regulation in prior research, namely: child cognitive skills, which could reflect the child’s ability to understand and perform the task; and the child’s baseline level of behavioral regulation, to account for the effects of dyadic contingencies above and beyond child regulatory ability (Dennis, 2006; Eisenberg et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2005). We studied children between 3½ and 4 years of age given that there is considerable variability and growth in self-regulation during the fourth year of life (Jones, Rothbart, & Posner, 2003) and that this period reflected the child’s first year in preschool, requiring regulatory adjustment to the school setting.

Method

Participants

Participants were 100 children and their families (54% female), identified as 86% White, 8% Biracial, 3% Asian, and 3% “other” race, and 10% Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Children were 41 months old on average (SD = 3) at Time 1 (T1) and 45 months (SD = 3) at Time 2 (T2). Median annual family income was $65,000 and parental education was high on average (college graduate). Of biological parents, 79% were married, 7% cohabiting, 7% single, 5% separated or divorced, and 1% remarried. Participants were recruited via flyers placed in day care centers, preschools, and businesses, and through email listserves of agencies serving families with young children. Families were excluded if children had a pervasive developmental disorder or if parents or children had a heart condition that interfered with physiological data collection.

Procedure

During a 2.5-hour laboratory visit at T1, mothers filled out questionnaires on themselves, their child, and their family including measures of child behavioral regulation, while the child was completing six tasks with the examiner including a cognitive assessment (Lunkenheimer, Albrecht, & Kemp, in press). Mothers and children also completed four dyadic tasks, including a problem-solving task. The remaining dyadic tasks (free play, cleanup, and an unfamiliar toy task), individual child tasks (e.g., object mastery, a disappointing toy, and a parent busy task), and physiological data collection were not examined for the purposes of the present study. Fathers’ questionnaires were mailed in or brought to the lab by the mother. Families were compensated $50 for laboratory sessions and mother questionnaires and $20 for father questionnaires. At T2, mothers, fathers, and teachers completed questionnaires online and were compensated with a $20 gift card, which was mailed to them.

At T1, 14 families had no father involvement because there was no father present or the father declined to participate. At T2, an additional 20 fathers were lost to attrition. There were no significant differences for these 20 families on sociodemographic measures (child age, SES, income, education, marital status, race, ethnicity) or study variables. At T2, 9 mothers were lost to attrition. These mothers had lower education, t(98) = −2.57, p < .05, and SES, t(98) = −2.92, p < .01, but no differences on other study variables. At T2, only 67 teachers participated due to difficulty contacting teachers or declined participation.

Measures

Parent-Child Challenge Task (PCCT)

The PCCT was developed by the first author to study dyadic patterns during a challenging, problem-solving situation. Mothers were instructed to help their children complete a puzzle using only their words (but not to physically help the child). Dyads worked on three puzzle designs from a guidebook that increased in difficulty (easy, moderate, difficult) and were given no time limit. The puzzle was designed for children 5 years and older and thus 3-year-olds could not complete it without assistance. It was made of 7 wooden pieces that fit together in various configurations to create castles. The mother was told that if they completed all three designs, the child would win a prize. This incentive was designed to encourage persistence at a difficult task; however, children received the prize regardless. The experimenter interrupted the dyad after four minutes to tell parents that they had only two minutes remaining, which initiated a “stressor” condition. However, for the purposes of the present study, only the baseline portion of the task (the first four minutes) was analyzed in order to understand the effects of maternal and child behaviors in typical problem-solving interactions. Three families were excluded from analysis due to equipment malfunction (n = 2) and speaking a language other than English (n = 1). This resulted in a valid N of 97 families for whom we had contingency data.

Mother and Child Behaviors

Mother and child behaviors were coded with the Dyadic Interaction Coding system (Lunkenheimer, 2009), which was adapted from the Relationship Process Code 2.0 (Dishion et al., 2008; Jabson, Dishion, Gardner, & Burton, 2004) and the Michigan Longitudinal Study (e.g., Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff, & Winter, 2011) coding systems. Behavioral observations were recorded using the Noldus Observer XT 8.0 software. Parents and children were each coded along two dimensions, affect and behavior, on a second-by-second basis, and codes were mutually exclusive. There were nine codes for parent behavior: teaching, directive, proactive structure, positive reinforcement, emotional support, engagement, disengagement, intrusion, and negative discipline. For the present study, only the teaching and directive codes were examined. The only other parent behavior likely to incur a compliant child response was proactive structure (e.g., redirection, positive reframing), but it was too infrequent to be analyzed (only 1% of parent behavior on average). There were seven codes for child behavior: compliance, persistence, social engagement, solitary/parallel play, noncompliance, nonpersistence, and emotional dysregulation. For the present study, only compliance was examined. If behaviors were repeated in quick succession with no new behavior being introduced (e.g., three directives in a row without giving the child an opportunity to respond), the series was considered a single event. Three undergraduate and graduate student coders were tested for reliability on 20% of the dataset in relation to a standard set by the first author and a trained graduate student. Reliability was calculated on an initial set of 10 videotapes, in addition to drift reliability assessed on an additional 10 tapes during the coding period. Reliability analysis was performed in the Noldus Observer 8.0 XT using a standard 3-second window.

Teaching was defined as instances when the parent explained how something worked (e.g., “ I think the red block goes in the middle” or “You might be able to flip it around”) or when the parent asked a question that allowed the child the opportunity to learn or respond (e.g., “What does the picture show?” “Where does this piece go?” or “How should we start making this Castle?”). Teaching questions or statements were open-ended and conveyed no specific direction. The frequency of teaching was represented by the number of maternal teaching comments or questions coded during the PCCT (kappa = .74).

Directives were defined as instances where the parent made clear commands for a specific response or behavior the parents did or did not want the child to enact. Directives included Do commands (e.g., Grab the blue block” or “Put it here”) and Don’t commands (e.g., “No, you do it” or “Don’t throw it”), as long as the Don’t commands were not harsh or critical. Harsh or critical directives were captured under another code called Negative Discipline, which was not examined in the present study. Directives also included “I want,” “I would like,” and “Please” statements (e.g., “Please put the top on”) because they required behavior change from the child. The frequency of directives was represented by the number of maternal directives coded during the PCCT (kappa = .76).

Compliance was defined as the act of clearly responding to parental Directives for specific behavior change (e.g., answering a parent’s command, placing a block in a certain location, ceasing off-task play) or responding to parental Teaching comments or questions (e.g., answering a parent’s question verbally, attempting a solution to the puzzle corresponding with a parent’s question about the puzzle). Compliance was coded if the child’s response occurred within 10 seconds of the parental behavior; if 10 seconds had passed without compliant behavior, then noncompliance was coded instead. This 10-second rule was based on our observation that responses to different parental behaviors may have required different underlying processes that took more or less time. For example, when children were given a choice as to their behavior (as opposed to a clear directive), they may have needed time in which to make that choice. The frequency of compliance was represented by the number of child compliance instances coded during the PCCT (kappa = .78).

Dyadic Contingencies

Dyadic contingencies were measured using transitional probabilities, calculated via state lag sequential analysis in the Noldus Observer 8.0 XT. A transitional probability was calculated based on the likelihood that the specific target behavior in question (e.g., child compliance) was the next behavior to directly follow after the start time of the criterion behavior in question (e.g., maternal directive). The time between the criterion and target behaviors could vary. These transitional probabilities were then averaged over the course of the interaction to produce the average transitional probability for that particular behavioral pairing for each dyad. Two mother-initiated contingency variables (Teaching→Compliance and Directive→Compliance) and two child-initiated contingency variables (Compliance→Teaching and Compliance→Directive) were computed for each dyad. The term “child-initiated” was used to be consistent in relation to describing “mother-initiated” contingencies, however, these “child-initiated” contingencies were technically preceded by a parental behavior given the way in which we coded child compliance.

Cognitive Skills

Cognitive skills were controlled for at T1 to account for the child’s baseline ability to perform the object assembly task in the PCCT. Cognitive skills have also been associated with child behavioral regulation in early childhood (Bell & Wolfe, 2004; Blair, 2002). The block design subtest of The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence third edition (WPPSI–III; Wechsler, 2002) assesses perceptual and visuo-spatial abilities as the child is asked to reproduce a series of pre-existing designs with a set of red and white blocks. The designs are time-limited, abstract, and increase in difficulty over time. There is a total possible score of 40 points for 20 items, and a higher score represents higher cognitive ability. Internal consistency has been shown to be high (α = .85; Wechsler, 2002).

Inhibitory Control (IC)

The 13-item IC subscale of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001) was used as an index of children’s behavioral regulation. Prior research has shown convergent validity between IC and other measures of behavioral regulation (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Kochanska, Murray, Jacques, Koenig, & Vandegeest, 1996; Olson et al., 2005). This subscale includes items such as “has difficulty waiting in line for something,” and “can easily stop an activity when s/he is told no.” Answers ranged from 1 (extremely untrue of child) to 7 (extremely true of child). Mothers’ ratings of IC at T1 were used as a control variable when predicting children’s behavioral regulation (IC) and dysregulation (externalizing behavior problems) at T2. Cronbach’s alpha reliability at T1 was .80. Cronbach’s alpha reliability at T2 was .79 for mothers, .77 for fathers, and .88 for teachers.

Externalizing Behavior Problems (EXT)

Externalizing problems were assessed via mother and father report on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/1.5–5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) EXT subscale, and teacher report on the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form (CTRF/1½–5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) EXT subscale. The EXT subscale reflects behavioral dysregulation in the form of poor attentional control and physically aggressive behavior. Convergent validity has been established with other measures of behavioral regulation and dysregulation in prior research (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Olson et al., 2005). Cronbach’s alpha reliability at T2 was .93 for mothers, .90 for fathers, and .93 for teachers.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses were performed to determine if variables differed by sociodemographic factors. No predictor or outcome variables were related to SES, maternal education, race, ethnicity, or gender. Child age at T1 was negatively correlated with the frequency of maternal directives (r = −.29, p < .01) and positively correlated with the probability that maternal directives were followed by child compliance (r = .31, p < .01), and thus was retained as a control variable. Table 1 includes descriptive statistics and Table 2 includes bivariate correlations among the study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data

| T1 Covariates | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Age (N=100) | 41.00 | 3.00 | 37.50–44.40 |

| Child Cognitive Skills (n=97) | 17.72 | 4.92 | 0.00–30.00 |

| Child Baseline IC (N=100) | 4.14 | .81 | 1.38–5.92 |

| T1 Predictors (n=97) | |||

| Maternal Teaching Frequency | 13.13 | 5.94 | 0.00–30.00 |

| Maternal Directive Frequency | 17.29 | 7.63 | 5.00–40.00 |

| Child Compliance Frequency | 10.08 | 4.35 | 4.00–25.00 |

| M Teaching-Compliance Contingency | .16 | .13 | 0.00–0.53 |

| M Directive-Compliance Contingency | .32 | .17 | 0.04–0.88 |

| C Compliance-Teaching Contingency | .20 | .15 | 0.00–0.75 |

| C Compliance-Directive Contingency | .13 | .13 | 0.00–0.67 |

| T2 Outcomes | |||

| Child IC Mother Rating (n=90) | 3.87 | .74 | 1.38–5.15 |

| Child IC Father Rating (n=66) | 3.99 | .75 | 2.54–5.46 |

| Child IC Teacher Rating (n=66) | 4.14 | 1.11 | 1.00–6.08 |

| Child EXT Mother Rating (n=91) | 7.91 | 7.34 | 0.00–31.00 |

| Child EXT Father Rating (n=66) | 10.94 | 6.85 | 0.00–30.00 |

| Child EXT Teacher Rating (n=67) | 8.01 | 8.97 | 0.00–41.00 |

Note: T1=Time 1; T2=Time 2; M=Mother-initiated; C=Child-initiated; IC=Inhibitory control; EXT=Externalizing behaviors

Table 2.

Correlations

| Covariates | Frequencies | Contingencies | Outcomes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| CA | CS | BI | TF | DF | CF | TC | DC | CT | CD | ICM | ICF | ICT | EXM | EXF | |

| Child Age (CA)

|

---- | ||||||||||||||

| Child Cognitive Skills (CS)

|

.38*** | ---- | |||||||||||||

| Child Baseline IC (BI) | .18† | .43*** | ---- | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Teaching Frequency (TF)

|

−.09 | −.09 | .09 | ---- | |||||||||||

| Directive Frequency (DF)

|

−.29** | −.21* | .06 | .57*** | ---- | ||||||||||

| Compliance Frequency (CF)

|

−.07 | −.04 | .00 | .54*** | .49*** | ---- | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Teaching-Compliance (TC)

|

.10 | .10 | −.12 | .01 | −.17 | .28** | ---- | ||||||||

| Directive-Compliance (DC)

|

.31** | .26* | .15 | −25* | −.36** | .17 | −.06 | ---- | |||||||

| Compliance-Teaching (CT)

|

.16 | .08 | .14 | .30** | .06 | .02 | −.30** | .21* | ---- | ||||||

| Compliance-Directive (CD)

|

−.13 | −.09 | −.04 | .20† | .23* | −.06 | .25* | −.45*** | −.31** | ---- | |||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| IC Mother (ICM)

|

.11 | .44*** | .63*** | .02 | −.01 | .06 | .12 | .33** | .06 | −.12 | ---- | ||||

| IC Father (ICF)

|

.00 | .26* | .38** | .19 | .00 | .08 | .01 | .11 | .18 | .08 | .44*** | ---- | |||

| IC Teacher (ICT)

|

.13 | .41*** | −.01 | .09 | −.15 | .11 | −.17 | .32** | .24* | −.14 | .20 | .06 | ---- | ||

| EXT Mother (EXM)

|

−.18† | .41*** | −.49** | .08 | .15 | .03 | −.15 | −.28** | .09 | .00 | −.71*** | −.49*** | −.14 | ---- | |

| EXT Father (EXF)

|

−.16 | −.51*** | −.44*** | −.16 | .02 | −.14 | −.14 | −.25* | −.23† | −.05 | −.46*** | −.56*** | −.24 | .52*** | |

| EXT Teacher

|

−.13 | −.38*** | −.06 | −.09 | .06 | −.05 | .18 | −.12 | −.23† | .09 | −.13 | −.16 | −.66*** | .21 | .29† |

Note: IC=Inhibitory control; EXT=Externalizing behaviors;

p <.10,

p <.05,

p <.01,

p <.001

We examined the distributions of the dyadic contingency variables to ensure that they were sufficiently frequent to employ them as predictors of child outcomes. All families showed Directive→Compliance contingency patterns, whereas 17 families showed no Teaching→Compliance contingencies, 15 families showed no Compliance→Teaching contingencies, and 29 families showed no Compliance→Directive contingencies (n = 97). All four contingency variables showed a normal distribution except for the Compliance Directive contingency, D(97) = 1.50, p < .05. Sequential analyses were conducted to ensure that the frequency of co-occurrences of these variable pairings occurred at a rate greater than chance (see Bakeman & Gottman, 1997; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2004). Co-occurrences between child compliance and maternal behaviors were examined within a two-second window in order to allow time for the partner’s response (Kiel, Gratz, Moore, Latzman, & Tull, 2011). Using pooled chi square analyses, observed co-occurrences in the total sample were compared to the expected frequency of these co-occurrences for the total sample, given the number of the behaviors (teaching, directives, or compliance) coded within each dyad. With respect to all four contingency patterns, the total number of observed contingency sequences across all dyads (264, 1116, 471, and 577, respectively, for Teaching→Compliance, Directive→Compliance, Compliance→Teaching, and Compliance→Directive) was significantly greater than that expected by chance (202, 285, 190, and 249, respectively). All chi square analyses were significant at the level of p < .001. We also examined which contingencies were more common, therefore whether teaching or directives were more likely to lead to compliance and whether compliance was more likely to lead to teaching or directives. Paired t-tests showed that directives were more likely to lead to compliance than was teaching (t = −7.11, df = 96, p < .001) and compliance was more likely to be followed by teaching than by directives, (t = 2.75, df = 96, p < .01).

As shown in Table 2, IC and EXT were significantly intercorrelated within rater. Further, ratings were correlated among parents but not across parents and teachers. Thus, a latent factor of behavioral regulation was created for each rater, with IC and EXT as the observed indicators. A confirmatory factor analysis model of parent ratings was performed in Mplus version 5 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007) using full information maximum likelihood estimation to confirm that a measurement model for parent ratings was warranted. This model of the two latent factors (mothers’ and fathers’ ratings) and the interrelation between them was an adequate fit to the data, χ2(6)=12.06, ns, CFI=.98, RMSEA=.07, SRMR=.04. In subsequent primary analyses, structural equation models were run separately for parent and teacher ratings given the lack of interrelation between parent and teacher ratings of child outcomes.

Primary Analyses

In primary analyses, we examined whether dyadic contingencies between maternal teaching and directives and child compliance at T1 predicted child IC and EXT at T2, controlling for the child’s age, cognitive skills, and IC at T1. We also compared the predictive utility of dyadic contingencies to frequencies of individual mother and child behaviors. Structural equation models were performed in Mplus version 5 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007) using full information maximum likelihood estimation, a method that accommodates missing data by estimating each parameter using all available data for that specific parameter. The comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were examined to assess model fit. CFI values of .90 and above indicate an adequate fit, and values of .95 and above indicate a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1995). RMSEA values less than .08 indicate adequate fit, and values less than .05 indicate a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). SRMR values less than .08 indicate a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1995). Models were tested separately by parent and teacher outcomes, and separately by mother-initiated versus child-initiated contingencies, resulting in four total models.

Mother-centered models

For mother-centered models, each model included three control variables (child age, cognitive skills, and IC at T1), two mother-initiated contingency variables (Teaching→Compliance and Directive→Compliance), the frequency of maternal teaching and directives, and the latent factors of child behavioral regulation outcomes (IC and EXT). The model for parent-rated outcomes will be presented first, followed by the model for teacher-rated outcomes.

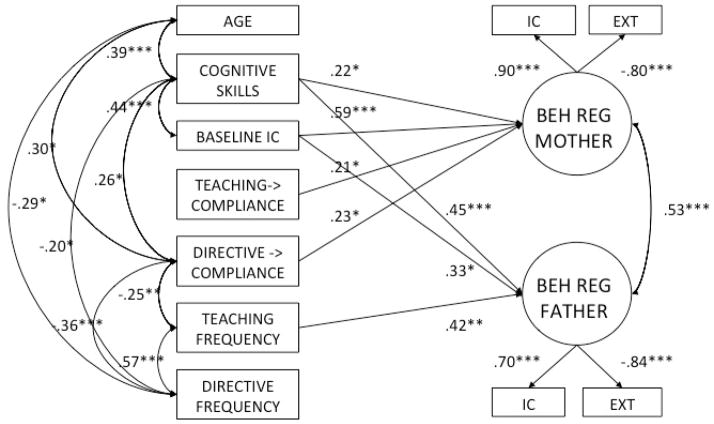

For the model predicting parent ratings of children’s behavioral regulation, model fit was adequate, χ2(15)=24.21, ns, CFI=.95, RMSEA=.08, SRMR=.04. Standardized parameters are shown in Figure 1. The stronger the probabilities that maternal teaching led to child compliance, and that maternal directives led to child compliance, the higher was the level of child behavioral regulation rated by mothers at T2. However, the frequencies of maternal teaching and directives were not predictive. Findings for fathers were different: a higher overall frequency of maternal teaching predicted children’s higher levels of behavioral regulation, but neither dyadic contingencies nor the overall frequency of maternal directives were predictive. Child age and cognitive skills were both positively associated with the stronger probability that maternal directives were followed by child compliance, and both negatively associated with the overall frequency of maternal directives. The frequencies of maternal teaching and directives were positively interrelated, but were both negatively associated with the probability that directives were followed by child compliance. This model accounted for 60% of the variance in the latent factor of mothers’ ratings, Est.=.60, SE=.08, p < .001, and 60% of the variance in the latent factor of fathers’ ratings of children’s behavioral regulation, Est.=.60, SE=.11, p < .001.

Figure 1.

Mother-Initiated Contingencies and Frequencies Predicting Parent Ratings of Child Behavioral Regulation. NOTE: Non-significant pathways are omitted; BEH REG = Behavioral Regulation; IC = Inhibitory control; EXT = Externalizing behaviors.

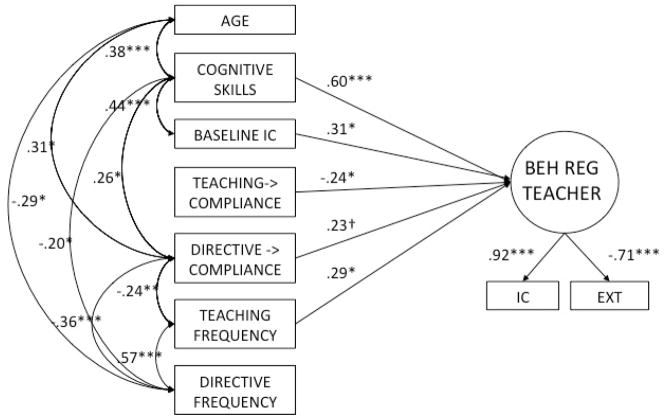

For the model predicting teacher ratings of children’s behavioral regulation, model fit was good, χ2(6)=4.76, ns, CFI=1.00, RMSEA=.00, SRMR=.02. Standardized parameters are shown in Figure 2. A stronger probability that maternal directives led to child compliance marginally predicted children’s better behavioral regulation at T2. Also, contrary to expectation, a stronger probability that maternal teaching led to child compliance predicted children’s poorer behavioral regulation. The overall frequency of maternal teaching at T1 once again significantly predicted children’s higher behavioral regulation. Interrelations among covariates and predictors were similar to those found in the model of parent ratings. This model accounted for 41% of the variance in the latent factor of children’s behavioral regulation, Est.=.41, SE=.12, p < .001.

Figure 2.

Mother-Initiated Contingencies and Frequencies Predicting Teacher Ratings of Child Behavioral Regulation. NOTE: Non-significant pathways are omitted; BEH REG = Behavioral Regulation; IC = Inhibitory control; EXT = Externalizing behaviors.

Given the unexpected finding that the Teaching→Compliance contingency was negatively associated with children’s behavioral regulation, post-hoc analyses were performed to further explore this relationship. Scatterplot graphs suggested a quadratic profile, in which high or low transitional probabilities were associated with better behavioral regulation, whereas moderate transitional probabilities were associated with poorer behavioral regulation. Thus, post-hoc regression analyses were performed, examining the contributions of linear and quadratic effects on this bivariate relationship. For IC, F(64)=4.00, p < .05, analyses confirmed that a quadratic effect of the contingency between maternal teaching and child compliance, B=.362, p < .05, predicted children’s IC accounting for the linear effect, B=−.379, p < .05, ΔR2 squared=.09, p < .05. Similarly, for EXT, F(65)=4.72, p < .05, analyses confirmed that a quadratic effect of the contingency between maternal teaching and child compliance, B=−.405, p < .05, predicted children’s EXT accounting for the linear effect, B=.435, p < .01, ΔR2 squared=.10, p < .05.

Child-centered models

For child-centered models, each model included three control variables (child age, cognitive skills, and IC at T1), two child-initiated contingency variables (Compliance→Teaching and Compliance→Directive), the frequency of child compliance, and the latent factors of child behavioral regulation outcomes (IC and EXT). The model for parent-rated outcomes will be presented first, followed by the model for teacher-rated outcomes.

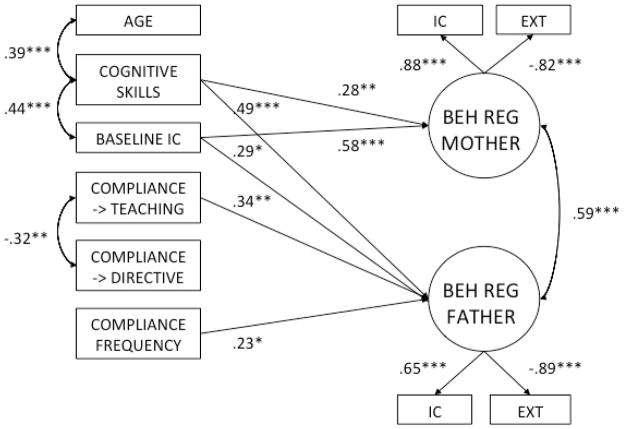

For the model predicting parent ratings of children’s behavioral regulation, model fit was adequate to weak, χ2(13)=23.35, p=.04, CFI=.94, RMSEA=.09, SRMR=.04. Standardized parameters are shown in Figure 3. In this model, neither dyadic contingencies nor the frequency of child compliance predicted mothers’ ratings of child behavioral regulation at T2. However, for fathers’ ratings, both the stronger probability that child compliance was followed by maternal teaching and the overall higher frequency of child compliance predicted higher behavioral regulation. There was also a significant negative relation between the probability that compliance was followed by a maternal directive and the probability that compliance was followed by maternal teaching. This model accounted for 54% of the variance in the latent factor of mothers’ ratings, Est.=.54, SE=.09, p < .001, and 61% of the variance in fathers’ ratings of children’s behavioral regulation, Est.=.61, SE =.11, p < .001.

Figure 3.

Child-Initiated Contingencies and Frequencies Predicting Parent Ratings of Child Behavioral Regulation. NOTE: Non-significant pathways are omitted; BEH REG = Behavioral Regulation; IC = Inhibitory control; EXT = Externalizing behaviors.

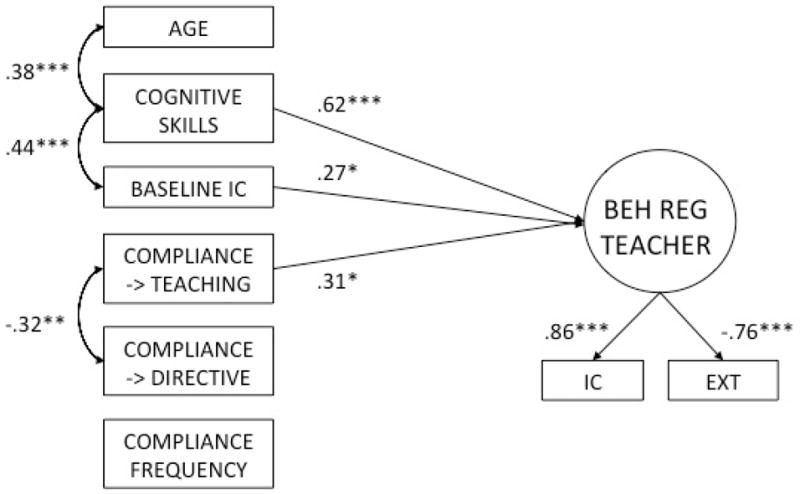

For the model predicting teacher ratings of children’s behavioral regulation, model fit was good, χ2(5)=1.82, ns, CFI=1.00, RMSEA=.00, SRMR=.02. Standardized parameters are shown in Figure 4. In this model, the stronger probability that child compliance was followed by maternal teaching was once again associated with children’s better behavioral regulation at T2. Interrelations among covariates and predictors were similar to those found in the model of parent ratings. This model accounted for 39% of the variance in the latent factor of children’s behavioral regulation, Est.=.39, SE=.12, p < .001.

Figure 4.

Child-Initiated Contingencies and Frequencies Predicting Teacher Ratings of Child Behavioral Regulation. NOTE: Non-significant pathways are omitted; BEH REG = Behavioral Regulation; IC = Inhibitory control; EXT = Externalizing behaviors.

Discussion

Self-regulation in preschool appears to be a key component of school readiness (Denham et al., 2012). Thus, an important question is how early teaching and learning contexts prior to school set the stage for behavioral regulation and dysregulation in the preschool years. Understanding the role of parent-child teaching interactions may inform the identification of malleable factors for the early promotion of behavioral regulation in learning contexts. Although the extant literature has shown mixed findings regarding the contributions of parental teaching to children’s self-regulation (Eisenberg et al., 2010; Landry et al., 2000), the present study took a different approach by reflecting the interdependent nature of parent-child teaching interactions using dyadic measures. Specifically, we examined whether observed dyadic contingencies between maternal teaching and directives and child compliance contributed to caregiver reports of children’s behavioral regulation and dysregulation in preschool. Findings revealed that mothers’ and children’s contingent responses to one another were predictive of children’s reported behavioral regulation in addition to what was predicted from the overall frequencies of observed mother and child behaviors. Further, effects differed depending on who initiated the contingent sequence (mother versus child) and who rated children’s behavioral regulation (mother, father, or teacher). Thus, the use of dyadic measures helped to inform our understanding of the conceptual link between parental teaching and children’s behavioral regulation in early childhood.

For mother-initiated contingency patterns, the stronger probability that maternal directives were followed by child compliance predicted children’s better behavioral regulation as rated by mothers and teachers. This finding supported prior research showing that contingent cycles of parental direction and child compliance are positively associated with reported behavioral regulation in early childhood (Cole et al., 2003; Dumas et al., 1995). Children who readily comply with their parents may have an easier time regulating their behavior and are likely seen by caregivers to be better regulated. This finding also suggested that maternal use of directives may have been developmentally appropriate in keeping 3½ year-olds focused in a difficult problem-solving situation (McNaughton & Leyland, 1999).

An important question of the present study was whether contingencies between maternal teaching and child compliance also predicted children’s reported behavioral regulation. We had hypothesized that teaching-related contingencies would be beneficial because by responding to learning opportunities, children would need to rely on their own thought processes (Sigel et al., 1993) and regulate their behaviors in a problem-solving situation. As hypothesized, contingent cycles of maternal teaching followed by child compliance predicted children’s better behavioral regulation as rated by mothers, controlling for the child’s age, cognitive skills, and baseline levels of behavioral regulation. Thus, when mothers offered the child chances to learn or respond and children took these opportunities, it may have help laid the groundwork for children’s regulatory abilities. Further, dyadic contingencies were better predictors of mothers’ ratings of child outcomes than overall frequencies of maternal behaviors, suggesting that the use of dyadic measures added to our existing understanding of the effects of mother-child teaching interactions.

Findings regarding teaching were different, however, when it came to teachers’ and fathers’ ratings of child outcomes. A higher overall frequency of maternal teaching was related to better behavioral regulation as rated by both fathers and teachers. This finding supported prior research (Hoffman et al., 2006; Landry et al., 2000; Supplee et al., 2004) suggesting that simply offering children instruction and opportunities to respond is important in promoting children’s behavioral regulation. Thus, we found evidence for both contingent responses to teaching and the overall amount of teaching in predicting children’s better behavioral regulation, depending upon who was rating child outcomes.

Unexpectedly, findings also showed an association between a stronger teaching-compliance contingency and teachers’ lower ratings of child behavioral regulation. A similar link has been found previously (Gartstein & Fagot, 2003). One possibility is that children who need high levels of guidance in learning situations at 3 years of age are perceived to have regulatory difficulties given the added attention teachers must pay to these children. On the other hand, post-hoc analyses revealed a curvilinear relationship, such that a very high or very low probability of a compliant child response to maternal teaching was associated with teachers’ higher ratings of child behavioral regulation. Perhaps highly contingent responses reflected the child’s willingness to respond to instruction, whereas no or weak contingencies reflected an already well-regulated and independent learner who did not need as much parental teaching. Although this finding needs to be replicated, it may help to explain mixed findings in prior research; complex relations between parent-child teaching interactions and children’s behavioral regulation may be partially explained by variation in the degree to which children make use of internally- versus externally-based regulatory processes.

Parent-child interactions are interdependent, and thus the frequency of observed child behaviors and their evocative effects on their mothers were also examined. When child compliance was followed predictably by additional parental teaching, this pattern was associated with children’s better behavioral regulation as rated by fathers and teachers (but not mothers). This finding supported prior work suggesting the importance of child effects on maternal teaching (Eisenberg et al., 2010). Collectively, our findings also extended prior work by showing evidence that both mothers’ and children’s contingent responses in real time contributed to the beneficial effects of the teaching and learning process. When children responded favorably to parental direction and teaching, parents may have responded by offering the child additional opportunities, creating a positive transactional process in service of the child’s regulatory ability. Further, child-initiated dyadic contingencies were stronger predictors of behavioral regulation than children’s overall levels of compliance, although compliance was also positively related to father reports of behavioral regulation.

On the whole, child-centered models showed lower goodness-of-fit than mother-centered models, likely because contingencies and frequencies were not predictive of mother-rated outcomes in these models. Perhaps shared method variance had contributed in part to the significant relations between maternal behaviors and maternal ratings of child outcomes in mother-centered models. It is also possible that child traits had differential effects in these models, given that caregiver familiarity with the child can account for differential variance among raters (Jensen, Xenakis, Davis, & DeGroot, 1988). We must consider whether contingencies based on transitional probabilities are the best way to capture evocative child effects at this age. In other words, although we expected parents to respond actively to their children (Robinson et al., 2009), children may not place the same degree of pressure on their parents for specific behavioral responses. Thus, child-centered models may have been weaker because our particular dyadic measure did not fully capture the variation in parents’ responses to their children. Regardless, the present study offered evidence that individual mother effects, individual child effects, and dyadic patterns should all be considered to represent a more complete picture of the effects of parent-child teaching interactions on children’s reported regulatory skills.

Another question is why there were differential effects by rater. Research has indicated that mothers’, fathers’, and teachers’ ratings explain unique variance in child behavior and that low to moderate agreement among caregivers is common (Berg-Nielsen, Solheim, Belsky, & Wichstrom, 2012; Kerr, Lunkenheimer, & Olson, 2007). We must also consider that variations in sample size across raters contributed to these differences, even though analytic models accounted for missing data. Dyadic interactions between fathers and children were not available, but other research has shown similarities and differences in how dyadic interaction patterns with mothers versus fathers affect children’s reported regulatory skills (Feldman, 2003; Lunkenheimer et al., 2011). Including observations of fathers in future research might help to tease apart differential variance due to rater characteristics versus that due to the varying effects of parent-child teaching processes upon behavior across the home and school contexts.

There were no effects of the overall frequency of maternal directives, nor directives that predictably followed child compliance. It is possible that maternal direction is only or particularly beneficial for children’s reported behavior regulation when it is part of a contingent behavioral sequence from parent to child. Parents are more likely to rely on directives when they have lower levels of SES (McLoyd, 1990) and research has shown differences in parental control behaviors by culture (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011). Thus, considering that our participants had higher levels of SES on average and were predominantly of non-Hispanic White race and ethnicity, it is possible that sample homogeneity affected the power with which to detect the effects of maternal direction. Higher SES and maternal education have also been positively associated with parents’ open-ended conversation with their children (Hall, Scholnick, & Hughes, 1987; Hoff-Ginsberg, 1994), so we may have seen greater variation in teaching behaviors with a more socioeconomically diverse sample. However, research has shown open-ended teaching behaviors to be protective for children in lower-income and higher-risk families (Landry et al., 2000; Supplee et al., 2004), and therefore these behaviors may be beneficial regardless of SES. Another remaining question is whether adding the variables of harsh discipline (e.g., directives with a critical tone) or child noncompliance (e.g., Dumas et al., 2001) would have provided a more complete picture of the relations between parental direction and children’s reported behavioral regulation. For example, noncompliance could have pulled for additional contingent directive responses on the part of the mother.

There were additional limitations to the present study. While the design allowed for the examination of processes during a period crucial to regulatory development, it is possible that the short time frame between the two assessments lessened the impact of predictive analyses. We were only able to assess parent-child interaction at the first time point, but multiple assessments could offer more information about relations between dyadic patterns and children’s developing regulatory skills over time. We utilized parent and teacher outcome reports, but having an observed behavioral regulation measure at T2 would have aided us in answering our questions. Further, we accounted for stability in child inhibitory control by controlling for this factor at T1, but did not account for change in the latent construct of behavioral regulation over time.

In conclusion, the present findings suggest that it is not only the parent’s or child’s individual behaviors that matter in parent-child interactions, but the patterning of the parent’s and child’s responses to one another that may be an important precursor of children’s regulatory competence across development (Cole et al., 2003; Dumas et al., 1995; Feldman, 2003). The process by which parent-child coregulation leads to children’s individualized self-regulatory ability during this crucial developmental stage could be better elucidated using dyadic and dynamic methods that reflex the complex nature of these processes (Olson & Lunkenheimer, 2009). These findings may also hold relevance for promoting school readiness, such that fostering parents’ open-ended teaching instruction and children’s use of such opportunities prior to former schooling may help lay the groundwork for their regulatory skills in learning situations.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Wolfe CD. Emotion and cognition: An intricately bound developmental process. Child Development. 2004;75:366–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Nielsen TS, Solheim E, Belsky J, Wichstrom L. Preschoolers’ psychosocial problems: In the eyes of the beholder? Adding teacher characteristics as determinants of discrepant parent–teacher reports. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2012;43:393–413. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomba AK, Goble CB, Moran JD. Maternal teaching behaviors and temperament in preschool children. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1994;78:403–406. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.78.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. California: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Wang TS. Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:489–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Teti LO, Zahn-Waxler C. Mutual emotion regulation and the stability of conduct problems between preschool and early school age. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM. Infant and maternal behaviors regulate infant reactivity to novelty at 6 months. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1123–1132. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Litman C. Autonomy as competence in 2-year-olds: Maternal correlates of child defiance, compliance, and self-assertion. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:961–971. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Alampay LP, Sorbring E, Bacchini D, Al-Hassan SM. The association between parental warmth and control in thirteen cultural groups. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:790–794. doi: 10.1037/a0025120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Warren-Khot HK, Bassett HH, Wyatt T, Perna A. Factor structure of self-regulation in preschoolers: Testing models of a field-based assessment for predicting early school readiness. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;111:386–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Workman E, Cole PM, Weissbrod C, Kendziora KT, Zahn-Waxler C. Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: The role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:23–45. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis T. Emotional self-regulation in preschoolers: The interplay of child approach reactivity, parenting, and control capacities. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:84–97. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, LaFreniere PJ, Serketich WJ. ‘Balance of power’: A transactional analysis of control in mother-child dyads involving socially competent, aggressive, and anxious children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:104–113. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes R, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Vidmar M, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND, Edwards A, Gaertner B, Kupfer A. Mothers’ teaching strategies and children’s effortful control: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1294–1308. doi: 10.1037/a0020236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, Gauvain M. Mother–child problem solving: Continuity through the early childhood years. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:480–488. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, McWayne C. The relationship between peer-play interactions in the family context and dimensions of school readiness for low-income preschool children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:79–87. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. Infant-mother and infant-father synchrony: The coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:1–23. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Fagot BI. Parental depression, parenting and family adjustment, and child effortful control: Explaining externalizing behaviors for preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:143–177. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(03)000431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:313–333. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404044530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore L, Cuskelly M, Jobling A, Hayes A. Maternal support for autonomy: Relationships with persistence for children with Down syndrome and typically developing children. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:1023–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Pomerantz E. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Development Perspectives. 2009;3:165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WS, Scholnick EK, Hughes AT. Contextual constraints on usage of cognitive words. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1987;16:289–310. doi: 10.1007/BF01069284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J. Balancing for weaknesses and challenging developmental potential: A longitudinal study of mother–infant dyads in apprenticeship interactions. In: Lloyd P, Fernyhough C, editors. Lev Vygotsky: Critical assessments. III. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge; 1999. pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff-Ginsberg E. Influences of mother and child on maternal talkativeness. Discourse Processes. 1994;18:105–117. doi: 10.1080/01638539409544886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Crnic KA, Baker JK. Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children’s emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6:271–295. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0604_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jabson JM, Dishion TJ, Gardner FEM, Burton J. Unpublished manual. University of Oregon; 2004. Relationship Process Code v2.0 Training Manual: A system for coding relationship interactions. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Xenakis SN, Davis H, DeGroot J. Child psychopathology rating scales and interrater agreement: Child and family characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:451–461. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198807000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LB, Rothbart MK, Posner MI. Development of executive attention in preschool children. Developmental Science. 2003;6:498–504. doi: 10.1111/1467-7687.00307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Lunkenheimer ES, Olson SL. Assessment of child problem behaviors by multiple informants: A longitudinal study from preschool to school entry. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:967–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Gratz KL, Moore SA, Latzman RD, Tull MT. The impact of borderline personality pathology on mothers’ responses to infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:907–918. doi: 10.1037/a0025474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Toward a synthesis of parental socialization and child temperament in early development of conscience. Child Development. 1993;64:325–347. doi: 10.2307/1131254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Coy KC, Murray KT. The development of self-regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1091–1111. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray K, Jacques TY, Koenig AL, Vandegeest KA. Inhibitory control in young children and its role in emerging internalization. Child Development. 1996;67:490–507. doi: 10.2307/1131828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Miller-Loncar CL. Early maternal and child influences on children’s later independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Development. 2000;71:358–375. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES. Unpublished manual. Colorado State University; 2009. Dyadic Interaction Code. [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Albrecht EC, Kemp CJ. Dyadic flexibility in early parent-child interactions: Relations with maternal depressive symptoms and child negativity and behavior problems. Infant and Child Development. doi: 10.1002/icd.1783. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell AM, Gardner F, Wilson MN, Skuban EM. Collateral benefits of the family check-up on early childhood school readiness: Indirect effects of parents’ positive behavior support. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1737–1752. doi: 10.1037/a0013858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Olson SL, Hollenstein T, Sameroff AJ, Winter C. Dyadic flexibility and positive affect in parent-child coregulation and the development of child behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:577–591. doi: 10.1017/S095457941100006X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys’ conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26(5):683–697. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.26.5.683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.2307/1131096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton S, Leyland J. The shifting focus of maternal tutoring across different difficulty levels on a problem-solving task. In: Lloyd P, Fernyhough C, editors. Lev Vygotsky: Critical assessments. III. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge; 1999. pp. 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney MK, McCartney K, Bub KL, Marshall NL. Determinants of dyadic scaffolding and cognitive outcomes in first graders. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6:297–320. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0604_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Lunkenheimer ES. Expanding concepts of self-regulation to social relationships: Transactional processes in the development of early behavioral adjustment. In: Sameroff AJ, editor. The transactional model of development. Washington, DC: APA; 2009. pp. 55–76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Kerr DCR, Lopez NL, Wellman HM. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: The role of effortful control. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:25–45. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Bank L. Some amplifying mechanisms for pathologic processes in families. In: Gunnar MR, Thelen E, editors. Systems and development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1989. pp. 167–209. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Kagan J. Infant predictors of kindergarten behavior: The contribution of inhibited and uninhibited temperament types. Behavioral Disorders. 2005;30:331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JB, Burns BM, Davis D. Maternal scaffolding and attention regulation in children living in poverty. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hersey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Chandler MJ. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking casualty. In: Horowitz FD, editor. Review of child development research. Vol. 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Sohr-Preston SL, Mirabile SP, Robison SD, Callahan KL. Parenting and children’s distress reactivity during toddlerhood: An examination of direction of effects. Social Development. 2008;17:578–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00439.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel IE, Stinson ET, Kim M. Socialization of cognition: The distancing model. In: Wozniak RH, Fischer KW, editors. Development in context: Acting and thinking in specific environments. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Supplee LH, Shaw DS, Hailstones K, Hartman K. Family and child influences on early academic and emotion regulatory behaviors. Journal of School Psychology. 2004;42:221–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2004.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wertsch JV. From social interaction to higher psychological processes: A clarification and application of Vygotsky’s theory. Human Development. 1979;22:1–22. doi: 10.1159/000272425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]